Abstract

Introduction

Evidence for the health harms of e-cigarettes is growing, yet little is known about which harms may be most impactful in health messaging. Our study sought to identify which harms tobacco product users were aware of and which most discouraged them from wanting to vape.

Methods

Participants were a convenience sample of 1,872 U.S. adult e-cigarette-only users, cigarette-only smokers, and dual users recruited in August 2018. In an online survey, participants evaluated 40 e-cigarette harms from seven categories: chemical exposures, device explosions, addiction, cardiovascular harm, respiratory harm, e-liquid toxicity, and other harms. Outcomes were awareness of the harms (“check all that apply”) and the extent to which the harms discouraged vaping (5-point scale; (1) “not at all” to (5) “very much”).

Results

Awareness of most e-cigarette harms was modest, being highest for harms in the device explosions category of harms (44%) and lowest for the e-liquid toxicity category (16%). The harms with the highest mean discouragement from wanting to vape were the respiratory harm (M = 3.82) and exposure to chemicals (M = 3.68) categories. Harms in the addiction category were the least discouraging (M = 2.83) compared with other harms (all p < .001). Findings were similar for e-cigarette-only users, cigarette-only smokers, and dual users.

Conclusions

Addiction was the least motivating e-cigarette harm, a notable finding given that the current FDA e-cigarette health warning communicates only about nicotine addiction. The next generation of e-cigarette health warnings and communication campaigns should highlight other harms, especially respiratory harms and the chemical exposures that may lead to health consequences.

Implications

E-cigarette health harms related to respiratory effects, chemical exposures, and other health areas most discouraged vaping among tobacco users. In contrast, health harms about addiction least discouraged use. Several countries have begun implementing e-cigarette health warnings, including the United States, and many others are considering adopting similar policies. To increase impact, future warnings and other health communication efforts should communicate about health harms beyond addiction, such as the effects of e-cigarette use on respiratory health. Such efforts should communicate that e-cigarette use is risky and may pose less overall risk to human health than smoking, according to current evidence.

Introduction

E-cigarette use in the United States is now a significant public health concern. According to national estimates, more than 15% of adults had tried an e-cigarette by 2016,1 and 4.5% (or approximately 11 million Americans) were current e-cigarette users in 2016.2 Although many experts agree that vaping is less harmful overall than smoking combustible cigarettes,3–6 e-cigarette use still poses health risks.7 For example, exposure to toxic chemicals in e-liquids (e.g., diacetyl, formaldehyde) has been associated with serious health harms, such as acute-onset bronchiolitis obliterans (i.e., “popcorn lung”)8,9 and DNA damage,7 and some correlational evidence has shown that current adult e-cigarette users are at an increased risk for developing asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.10 In addition, exposure to e-cigarette liquids has led to seizures, anoxic brain injury, and vomiting.7,11 Several reports have also documented e-cigarette device explosions,7,12 which can cause skin and oral burns, as well as other serious fire-related injuries.13 Finally, some evidence shows that use of e-cigarettes is associated with negative cardiovascular effects, such as increased blood pressure and heart rate, and myocardial infarction.7,14,15

Another major concern about e-cigarette use has to do with nicotine exposure and addiction. Most e-cigarette products contain nicotine,16,17 and JUUL pods deliver a particularly addictive form of nicotine in very high doses.18 Repeated exposure to nicotine through use of e-cigarettes could lead to eventual use of and possible addiction to combustible cigarettes and other tobacco products.19,20 A recent study of adult smokers found that rather than supporting quitting, e-cigarette use was associated with heavier cigarette smoking.21

Despite mounting evidence, risk perceptions about the harms associated with using e-cigarettes remain relatively low.22 Health communications (including health warnings and mass media campaigns) could inform the public about the risks of using e-cigarettes and discourage vaping. Such efforts are increasingly important among populations most susceptible to the harms of e-cigarettes, such as current adult tobacco users who may perceive these products to be useful for smoking cessation purposes,23 but instead become dual users of both cigarettes and e-cigarettes. To date, however, little is known about consumers’ awareness of e-cigarette harms and which e-cigarette harms are most likely to discourage vaping. Thus, to inform communications efforts and warning development, we sought to examine which e-cigarette health harms tobacco users were aware of and which most discouraged use of e-cigarettes.

Methods

Participants

Participants were a convenience sample of U.S. adults, ages 18 or older, who currently smoked or vaped, as part of a larger investigation about e-cigarette warnings in August 2018.24 A total of 1,872 individuals completed the current study. Participants were current e-cigarette users (defined as someone who has vaped in the past 30 days and who currently vapes some days or every day25), current smokers (defined as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes and now smoking some days or every day26,27), or dual users (defined as being a current smoker and e-cigarette user). Recruitment took place through TurkPrime’s Prime Panels,28 an online platform with access to over 20 million participants for behavioral research.29 Online convenience samples are an efficient and cost-effective way to study health behavior, and experiments conducted in convenience samples tend to yield identical patterns as those conducted in representative samples.30

Procedure

After providing informed consent, participants completed an online survey about e-cigarette health warnings.24 About halfway through the survey, participants answered awareness and discouragement items about e-cigarette harms and hazards. For simplicity, we refer to e-cigarette hazards as “harms” in this paper. We presented 40 different e-cigarette harms based on the landmark 2018 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report on e-cigarette harms7 and other literature.19 For 38 harms, the data were conclusive. For two harms (lung disease and heart disease), the data were suggestive but not conclusive.7 We grouped these 40 harms into seven categories for this study: device explosions, addiction, cardiovascular harm, respiratory harm, e-liquid toxicity, chemical exposures, and other harms. Because the chemical exposures category was the longest (12 harms), we separated it into two sets. Thus, the study had eight possible categories that participants could see.

Given the large number of e-cigarette health harms, we employed a split-panel design in which we randomized participants into one of four panels. In each panel, participants evaluated 10 e-cigarette harms (~4–6 harms drawn from each of two different harm categories). To reduce potential order effects, we randomized the order in which participants viewed each category and saw their respective harms. Upon completion of the survey, participants received incentives in the reward type and amount determined through their respective Prime Panels market research platform (e.g., cash, gift cards, or reward points). The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Measures

Awareness of E-Cigarette Harms

Awareness was assessed by asking, “Before today, had you ever heard that using e-cigarettes causes these risks?” This prompt was followed by a list of harms associated with each participants’ randomly assigned panels. Responses used a “check all that apply” format and included a “none of the above” option.

Discouragement From Using E-Cigarettes

Discouragement was assessed using a single item for each harm. Participants were asked, “E-cigarettes may expose users to the risks we just asked you about. How much does knowing that using e-cigarettes causes these risks discourage you from wanting to vape?” Participants were given the same randomized set of e-cigarette harms and rated each on discouragement. Responses were on a 5-point scale ranging from “not at all” (coded as 1) to “very much” (5).

Tobacco Product Use

Current e-cigarette use was assessed by asking participants if they had used an e-cigarette product in the past 30 days and if they currently vaped some days or every day. Current cigarette smoking was assessed by asking participants if they had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, and if they now smoked some days or every day. Current use of other tobacco products was assessed by having participants select other tobacco products (traditional cigars, hookah, and little cigars and cigarillos) that they had used in the past 30 days.

Demographic Characteristics

We assessed participant age, sex, education, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and annual household income.

Data Analysis

We computed mean percent awareness and discouragement for each e-cigarette health harm category by averaging across all harms in a given category. To identify correlates of harm-induced discouragement from using e-cigarettes, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for our repeated-measures design with the identity link to model the continuous outcomes. The main predictor was exposure to one of the seven health harm categories; the addiction harm category was the reference category because that is most similar to the current e-cigarette pack warning label required by the FDA.31 Covariates were age, race (white vs. other), ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, education (no bachelor’s degree vs. bachelor’s degree or higher), current other tobacco product use, and whether participants were current e-cigarette users, cigarette smokers, or dual users. To further explore if cigarette smokers, dual users, and e-cigarette only users differed on harm discouragement, we stratified the analyses by tobacco user type. We report results of the GEE models as unstandardized regression coefficients (b). Critical alpha was 0.05, except for the stratified analyses of the three types of tobacco users, for which we set critical alpha at .0167 (.05/3) to correct for Type 1 error. All statistical tests were two-tailed. Analyses were conducted using R (version 3.4.3).32,33

Results

Participant Characteristics

The average age of participants was 43 (Table 1). The majority of participants were female (54%) and white (80%), and only 24% of participants had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Most (59%) made less than US$50,000 per year. A minority of participants reported being gay, lesbian, or bisexual (10%). Participants used e-cigarettes only (19%), smoked cigarettes only (40%), or were dual users (41%). Other current tobacco product use included little cigars and cigarillos (20%), traditional cigars (17%), and hookah (9%).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (N = 1,872)

| Panel 1 | Panel 2 | Panel 3 | Panel 4 | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 478) | (n = 451) | (n = 470) | (n = 473) | (n = 1,872) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age, mean years | 43.00 | 43.37 | 42.79 | 43.54 | 43.17 |

| (SD) | (15.21) | (14.45) | (14.29) | (14.18) | (14.53) |

| [range] | [18–83] | [18–80] | [19–85] | [18–81] | [18–85] |

| Age, years | |||||

| 18–25 | 61 (13) | 41 (9) | 49 (10) | 48 (10) | 199 (11) |

| 26–34 | 105 (22) | 111 (25) | 120 (26) | 100 (21) | 437 (23) |

| 35–44 | 115 (24) | 109 (24) | 100 (22) | 114 (24) | 437 (23) |

| 45–54 | 64 (13) | 71 (16) | 75 (16) | 89 (19) | 299 (16) |

| 55–64 | 83 (17) | 76 (17) | 91 (19) | 80 (17) | 330 (18) |

| 65+ | 50 (11) | 43 (9) | 35 (7) | 42 (9) | 170 (9) |

| Race | |||||

| American Indian or Alaskan native | 12 (3) | 10 (2) | 12 (3) | 4 (1) | 38 (2) |

| Asian | 16 (3) | 20 (4) | 15 (3) | 20 (4) | 71 (3) |

| Black or African American | 34 (7) | 54 (12) | 47 (10) | 51 (11) | 186 (10) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 9 (1) |

| White | 389 (81) | 349 (77) | 378 (80) | 376 (79) | 1492 (80) |

| Other | 24 (5) | 16 (4) | 16 (3) | 20 (4) | 76 (4) |

| Hispanic | 43 (9) | 36 (8) | 36 (8) | 40 (8) | 155 (8) |

| Female | 262 (55) | 245 (54) | 261 (55) | 252 (53) | 1,020 (54) |

| Gay, lesbian or bisexual | 54 (11) | 38 (8) | 48 (10) | 43 (9) | 183 (10) |

| Education | |||||

| High school or less | 145 (30) | 127 (28) | 149 (32) | 141 (30) | 562 (30) |

| Some college | 139 (29) | 141 (31) | 145 (30) | 154 (32) | 579 (31) |

| College graduate or associate’s degree | 161 (34) | 144 (32) | 146 (31) | 141 (30) | 592 (32) |

| Graduate degree | 25 (5) | 33 (7) | 27 (6) | 30 (6) | 115 (6) |

| Did not answer | 8 (2) | 6 (2) | 3 (1) | 7 (2) | 24 (1) |

| Household income, annual | |||||

| US$0–US$24,999 | 105 (22) | 129 (29) | 140 (30) | 129 (27) | 503 (27) |

| US$25,000–US$49,999 | 162 (34) | 142 (31) | 142 (30) | 141 (30) | 587 (32) |

| US$50,000US$74,999 | 87 (18) | 88 (20) | 91 (19) | 98 (21) | 364 (19) |

| US $75,000+ | 116 (24) | 87 (19) | 93 (19) | 97 (20) | 393 (21) |

| Did not answer | 8 (2) | 5(1) | 4 (1) | 8 (2) | 25 (1) |

| Type of tobacco user | |||||

| E-cigarettes only | 112 (23) | 72 (16) | 87 (19) | 79 (17) | 350 (19) |

| Cigarettes only | 190 (40) | 182 (40) | 190 (40) | 187 (40) | 749 (40) |

| Dual user | 176 (37) | 197 (44) | 193 (41) | 207 (44) | 773 (41) |

| Other tobacco product use | |||||

| LCC | 87 (18) | 100 (22) | 87 (19) | 100 (21) | 374 (20) |

| Traditional cigars | 74 (15) | 85 (19) | 89 (19) | 72 (15) | 320 (17) |

| Hookah | 43 (9) | 37 (8) | 47 (10) | 42 (9) | 169 (9) |

SD = standard deviation, LCC = little cigars and cigarillos. All current tobacco use is past 30 days, except cigarette smoking which refers to adults who have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their life and now smoke some days or every day.

Prevalence of Awareness and Discouragement

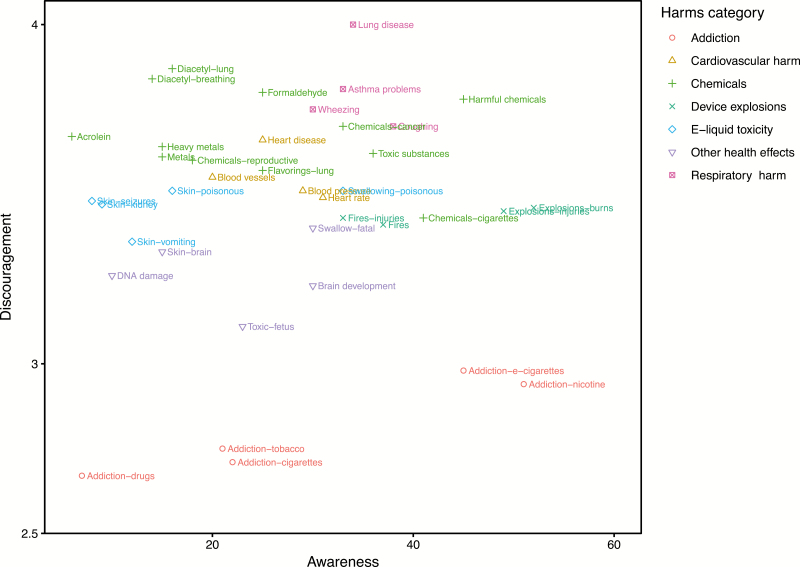

Awareness of e-cigarette harms was modest at best, with awareness of device explosions being highest (44%; Table 2), followed by respiratory harm (34%), addiction (29%), one of the two chemical sets (28%), and cardiovascular harm (26%). Awareness of the remaining health harms was low, with fewer than one-quarter of participants being aware of other health effects (22%) and the second set of chemicals (21%). Participants were least aware of e-liquid skin contact harms (16%). Within each of these categories, individual harms showed substantial variability. For example, 45% of participants were aware that use of e-cigarettes could lead to addiction, but only 7% were aware that e-cigarette use could increase one’s chances of addiction to other harmful drugs (Figure 1).

Table 2.

E-cigarette health harms: discouragement and awareness (N = 1,872)

| Discouragement | Awareness | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | % | |

| Respiratory harms2 | 3.82 | 1.20 | 34 |

| Lung disease | 4.00 | 1.21 | 34 |

| Asthma problems | 3.81 | 1.29 | 33 |

| Wheezing | 3.75 | 1.27 | 30 |

| Coughing | 3.70 | 1.29 | 38 |

| Chemicals set 22 | 3.76 | 1.19 | 21 |

| Exposure to diacetyl, which can cause lung disease | 3.87 | 1.26 | 16 |

| Exposure to diacetyl, which can cause permanent breathing problems | 3.84 | 1.27 | 14 |

| Exposure to formaldehyde | 3.80 | 1.25 | 25 |

| Exposure to harmful chemicals | 3.78 | 1.27 | 45 |

| Exposure to acrolein | 3.67 | 1.32 | 6 |

| Exposure to chemicals that cause reproductive harm | 3.60 | 1.38 | 18 |

| Chemicals set 11 | 3.59 | 1.21 | 28 |

| Exposure to chemicals that cause cancer | 3.70 | 1.29 | 33 |

| Exposure to heavy metals such as nickel, tin, and lead which can be inhaled deep into the lungs | 3.64 | 1.32 | 15 |

| Exposure to toxic substances | 3.62 | 1.29 | 36 |

| Exposure to metals | 3.61 | 1.32 | 15 |

| Exposure to flavorings that are linked to lung disease | 3.57 | 1.31 | 25 |

| Exposure to some of the same chemicals in cigarette smoke | 3.43 | 1.33 | 41 |

| Cardiovascular harms1 | 3.55 | 1.26 | 26 |

| Heart disease | 3.66 | 1.30 | 25 |

| Harm to blood vessels | 3.55 | 1.32 | 20 |

| Increased blood pressure | 3.51 | 1.32 | 29 |

| Increased heart rate | 3.49 | 1.31 | 31 |

| E-liquid toxicity3 | 3.47 | 1.38 | 16 |

| Swallowing e-liquids can be poisonous to the body | 3.51 | 1.46 | 33 |

| E-liquid skin contact can be poisonous to the body | 3.51 | 1.44 | 16 |

| E-liquid skin contact can cause seizures | 3.48 | 1.45 | 8 |

| E-liquid skin contact can cause kidney problems | 3.47 | 1.44 | 9 |

| E-liquid skin contact can cause vomiting | 3.36 | 1.46 | 12 |

| Device explosions3 | 3.43 | 1.38 | 44 |

| E-cigarette explosions that cause burns | 3.46 | 1.40 | 52 |

| E-cigarette explosions | 3.45 | 1.41 | 49 |

| E-cigarette explosions that cause injuries | 3.45 | 1.40 | 49 |

| E-cigarette fires that cause injuries | 3.43 | 1.43 | 33 |

| E-cigarette fires | 3.41 | 1.43 | 37 |

| Other health effects4 | 3.27 | 1.33 | 22 |

| Swallowing e-liquids can be fatal | 3.40 | 1.48 | 30 |

| E-liquid skin contact can reduce oxygen to your brain, causing brain injury | 3.33 | 1.42 | 15 |

| DNA damage | 3.26 | 1.47 | 10 |

| Harm to adolescent and young adult brain development | 3.23 | 1.50 | 30 |

| Toxic to developing fetus | 3.11 | 1.57 | 23 |

| Addiction4 | 2.81 | 1.30 | 29 |

| Addiction to e-cigarettes | 2.98 | 1.40 | 45 |

| Addiction to nicotine | 2.94 | 1.42 | 51 |

| Increased chance of using other tobacco products | 2.75 | 1.49 | 21 |

| Increased chance of smoking cigarettes | 2.71 | 1.47 | 22 |

| Increased chance of getting addicted to drugs | 2.67 | 1.56 | 7 |

E-cigarette harms are ordered from most to least discouraging in each harm category. M = mean, SD = standard deviation. Harm category means for awareness and discouragement were calculated from only their respective harm items. Superscripts refer to survey panel number (panel 1: n = 478; panel 2: n = 451; panel 3: n = 470; panel 4: n = 473).

Figure 1.

E-cigarette health harms by discouragement and awareness. We combined both chemical health harm categories (sets 1 and 2) for image clarity. E-cigarette health harms by discouragement and awareness; chemical harm categories 1 and 2 combined.

Regarding discouragement, participants rated harms in the respiratory category as most discouraging them from wanting to vape (Mean [M] = 3.82), followed by the two sets of chemical exposures (set 2: M = 3.76; set 1: M = 3.59), cardiovascular harms (M = 3.55), harms related to e-liquid toxicity (M = 3.47), harms related to device explosions (M = 3.43), and other health harms (M = 3.27). Addiction was the least discouraging health harm category (M = 2.81). Within categories, individual harms showed some variability (Table 2).

Correlates of Discouragement

Every health harm category was more discouraging than the addiction harm category in adjusted analyses (Table 3). Thus, respiratory, cardiovascular, chemical, e-liquid toxicity, device explosions, and other health harms discouraged tobacco users from using e-cigarettes more than harms related to addiction (all p < .001).

Table 3.

Correlates of discouragement from using e-cigarettes (N = 1,847)

| b | SE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics | |||

| Age | .01 | .00 | .010 |

| White | −.25 | .07 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | .16 | .09 | .085 |

| Female | .35 | .06 | <.001 |

| Gay, lesbian, or bisexual | −.19 | .10 | .049 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | .03 | .06 | .631 |

| OTP user | .17 | .06 | .008 |

| Type of tobacco user | |||

| Only cigarettes | REF | REF | |

| Only e-cigarettes | −.75 | .08 | <.001 |

| Dual user | −.39 | .06 | <.001 |

| Message characteristics | |||

| Health harm category | |||

| Addiction | REF | REF | |

| Other health effects | .46 | .04 | <.001 |

| Device explosions | .62 | .08 | <.001 |

| E-liquid toxicity | .65 | .08 | <.001 |

| Chemicals set 2 | .78 | .08 | <.001 |

| Chemicals set 1 | .81 | .08 | <.001 |

| Cardiovascular harm | .93 | .08 | <.001 |

| Respiratory harm | .99 | .08 | <.001 |

The table shows unstandardized regression coefficients (b) and standard errors (SE); outcome was discouragement from smoking (1 = not at all, to 5 = a lot).

Several covariates also predicted discouragement. For example, participants who were white (p < .001; Table 3), as well as those who were either gay, lesbian, or bisexual (p = .049), were less discouraged from wanting to vape after exposure to harms than those who were not. In addition, e-cigarettes harms were more discouraging to participants who were older (p = .010), female (p < .001), or current other tobacco product users (p = .008). Compared with those who only smoked combustible cigarettes, e-cigarettes harms were less discouraging to e-cigarette only users (p < .001) and dual users of both cigarettes and e-cigarettes (p < .001).

Stratifying the analyses by tobacco user type yielded the same pattern of results (Supplementary Table 1). For both cigarette smokers and dual users, every health harm category was more discouraging than the addiction harm category (all p < .001). For e-cigarette users, every health harm category was more discouraging than the addiction harm category (all p < .001) except for device explosions (p = .039).

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine which e-cigarette health harms tobacco users were aware of and which most discouraged use of e-cigarettes. We found that awareness of e-cigarette health harms was low to moderate at best, and that addiction-related health harms least motivated tobacco users from wanting to vape than all other harm categories tested. These results can inform future e-cigarette product warnings and other health communication efforts targeted toward tobacco users. At least 14 countries have already required e-cigarette health warning labels,34 and many others are considering implementing similar policies.

Roughly one-third of participants were aware that e-cigarette use may have negative respiratory health effects (e.g., wheezing, coughing) and only 16% were aware of the toxic nature of e-cigarette liquid (e.g., exposure to liquids causing seizures, vomiting). The greatest awareness was for the device explosion harm category (44%), but even those harms were not known by a majority of tobacco users. We also found that few participants in our study (22%) were aware that using e-cigarettes could increase their likelihood of smoking combustible cigarettes. Although these estimates come from a sample that may not necessarily generalize to the population, it still suggests that only modest proportions of tobacco users are aware of many of the health harms of e-cigarettes. Thus, communication efforts should consider how to raise awareness about e-cigarettes as a means to initiate other tobacco product use, especially among young adult e-cigarette-only users who have a high risk of future combustible cigarette smoking initiation35 and subsequent lifelong addiction.36 In addition, roughly 40% of our participants reported being dual users of both cigarettes and e-cigarettes. Recent evidence shows that, compared with cigarette-only smokers, dual users tend to smoke more cigarettes per day and are at a higher risk of experiencing cardiopulmonary harm.37 As such, there is a need for tobacco control efforts to increase awareness about the harms of dual use.

We found that, overall, harms related to respiratory effects and chemical exposures most discouraged tobacco users from wanting to vape; though, harms related to cardiovascular effects, e-liquid toxicity, and e-cigarette device explosions categories were also relatively discouraging. In addition, analyses stratified by tobacco user type revealed a very similar pattern of discouragement findings for cigarette smokers, dual users, and e-cigarette only users. Notably, participants rated addiction as the least discouraging e-cigarette health harm—lower than all other harms tested in this study. This is consistent with other previous work that has found addiction to be the least discouraging harms message for cigarette smoking.38 Addiction messages may tell tobacco users something they already know, whereas messages with other harms may be more informative and novel. Also, research has suggested that messages that demonstrate the consequences of addiction, such as loss of control or reduced independence,39 may be more impactful than messages that do not communicate how addiction may impact one’s life.

Currently, the U.S. FDA requires a warning about nicotine addiction for all e-cigarette packages and advertisements.31 Given that we found addiction to be the least discouraging harm, e-cigarette warnings could be strengthened by focusing on other types of harms. For example, additional warnings about the possible effects of e-cigarettes on respiratory health, as well as exposure to chemicals or heavy metals that may cause health harms, could increase the impact of warnings. It is important, however, that e-cigarette warnings do not inadvertently deter current cigarette smokers (or dual users) away from switching entirely to e-cigarettes as evidence suggests e-cigarettes are likely less harmful than combustible cigarettes.7 A recent nationally representative study found that since 2014, adult smokers and e-cigarette users’ perceptions that e-cigarettes are more harmful than combustible cigarettes have been increasing.40 Thus, it is critical that future warnings aim to strike a careful balance in conveying that while e-cigarettes may be less harmful than combustible cigarettes, they are risky to use. Using text-only warnings to communicate risks of e-cigarette use would likely achieve that purpose, as could considering relative risk messages that communicate risks of e-cigarette use while making it clear that the harm is lower than cigarette smoking.41 An example would be, “E-cigarettes expose users to harmful chemicals, but this exposure is lower than from regular cigarettes.”

Finally, while findings were similar across tobacco product user groups, there is still a need for targeted communications given the different tobacco products used by each group. For instance, cigarette smokers should be strongly encouraged to quit smoking using any and all quit methods, including use of e-cigarettes, and relative risk messages (that contextualize e-cigarette harms in relation to cigarette smoking harms) may be helpful in that regard.42 It is important to recognize that cigarette smokers were highly discouraged by e-cigarette harms. Given that the harms posed by cigarettes (which they currently regularly smoke) are known to be so much more dangerous, it is critical that e-cigarette harm messages do not unintentionally prevent cigarette smokers from switching to vaping. In contrast, e-cigarette only users may best benefit from strong messages about the harms of e-cigarette use and the benefits of quitting. Finally, dual users may benefit from messages about the unique risks of dual use, as well as relative risk messages that encourage them to quit smoking. Targeted communication efforts—such as communication campaigns—should be developed and disseminated with messages customized for these unique tobacco user groups. Although not in the immediate scope of this current study, nontobacco users and adolescents would also benefit from messages about the risks of e-cigarettes to prevent new tobacco users.

Strengths of our study include a large national sample of current tobacco users, and the evaluation of 40 different e-cigarette health harms. Study limitations include the use of a convenience sample that was, for example, mostly white. Although past work suggests that online convenience samples can provide similar experimental results when compared with probability samples,30,43,44 confirming our findings in a probability sample would be useful, in particular for generating national probability estimates of e-cigarette harm awareness. Another limitation is our use of a split-panel study design in which each participant only responded to two sets of e-cigarette harms. Although our study design was necessary to reduce participant burden, future investigations might apply other designs, such as having participants evaluate multiple e-cigarette health harms from many different harm categories. Finally, our study evaluated only the harms themselves; a future study should test a variety of warnings or other messages that feature these harms and examine their impact on beliefs and behavior.

Conclusion

Our convenience sample of U.S. tobacco users had only modest awareness of the harms of e-cigarette use. Moreover, addiction was the least discouraging e-cigarette health harm—a notable problem given that the current FDA e-cigarette warning only communicates about addiction.31 As such, we suggest that the next generation of warnings and other e-cigarette-related health communication efforts include various other health harms, such as the effects of e-cigarette use on respiratory health, exposure to toxic chemicals found in e-cigarette vapor, or burns resulting from e-cigarette device explosions. Such communications should take care, however, to ensure smokers understand that while e-cigarettes pose health harms, the evidence to date suggests that such harms are significantly less than those posed by smoking cigarettes.

Supplementary Material

Funding

Research reported in this paper was supported by grant number 5P50CA180907 from the National Cancer Institute and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP). T32-CA057726 from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health and K01HL147713 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health supported Marissa Hall’s time on the paper. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Declaration of Interests

Drs. Ribisl and Brewer have served as paid expert consultants in litigation against tobacco companies. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Bao W, Xu G, Lu J, Snetselaar LG, Wallace RB. Changes in electronic cigarette use among adults in the United States, 2014-2016. JAMA. 2018;319(19):2039–2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mirbolouk M, Charkhchi P, Kianoush S, et al. Prevalence and distribution of E-Cigarette use among U.S. adults: Behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2016. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):429–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ratajczak A, Feleszko W, Smith DM, Goniewicz M. How close are we to definitively identifying the respiratory health effects of e-cigarettes? Expert Rev Respir Med. 2018;12(7):549–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rigotti NA. Balancing the benefits and harms of E-Cigarettes: A National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine Report. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(9):666–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen J, Bullen C, Dirks K. A comparative health risk assessment of electronic cigarettes and conventional cigarettes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(4):382–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bhatnagar A, Whitsel LP, Ribisl KM, et al. ; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Electronic cigarettes: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130(16):1418–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barrington-Trimis JL, Samet JM, McConnell R. Flavorings in electronic cigarettes: An unrecognized respiratory health hazard? JAMA. 2014;312(23):2493–2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Allen JG, Flanigan SS, LeBlanc M, et al. Flavoring chemicals in E-Cigarettes: Diacetyl, 2,3-Pentanedione, and Acetoin in a Sample of 51 Products, Including Fruit-, Candy-, and Cocktail-Flavored E-Cigarettes. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124(6):733–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wills TA, Pagano I, Williams RJ, Tam EK. E-cigarette use and respiratory disorder in an adult sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;194:363–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Solarino B, Rosenbaum F, Riesselmann B, Buschmann CT, Tsokos M. Death due to ingestion of nicotine-containing solution: Case report and review of the literature. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;195(1-3):e19–e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rossheim ME, Livingston MD, Soule EK, Zeraye HA, Thombs DL. Electronic cigarette explosion and burn injuries, US emergency departments 2015–2017. Tob Control. 2019;28:472–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alzahrani T, Pena I, Temesgen N, Glantz SA. Association between electronic cigarette use and Myocardial infarction. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(4):455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bhatta DN, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarette use and myocardial infarction among adults in the US population assessment of tobacco and health. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(12):e012317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16. Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes: A scientific review. Circulation. 2014;129(19):1972–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marynak KL, Gammon DG, Rogers T, Coats EM, Singh T, King BA. Sales of Nicotine-Containing Electronic Cigarette Products: United States, 2015. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):702–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barrington-Trimis JL, Leventhal AM. Adolescents’ Use of “Pod Mod” E-Cigarettes - Urgent Concerns. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(12):1099–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Watkins SL, Glantz SA, Chaffee BW. Association of noncigarette tobacco product use with future cigarette smoking among youth in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, 2013-2015. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(2):181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Olfson M, Wall MM, Liu SM, Sultan RS, Blanco C. E-cigarette use among young adults in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(5):655–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pepper JK, Brewer NT. Electronic nicotine delivery system (electronic cigarette) awareness, use, reactions and beliefs: A systematic review. Tob Control. 2014;23(5):375–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Patel D, Davis KC, Cox S, et al. Reasons for current E-cigarette use among U.S. adults. Prev Med. 2016;93:14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brewer NT, Jeong M, Hall MG, et al. Impact of e-cigarette health warnings on motivation to vape and smoke. Tob Control. 2019;28:e64–e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. PATH. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tobacco use among middle and high school students - United States, 2011-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(14):381–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Davis S, Malarcher A, Thorne S, Maurice E, Trosclair A, Mowery P. State-specific prevalence and trends in adult cigarette smoking-United States, 1998–2007. MMWR-Morbid Mortal W. 2009;58(9):221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. TurkPrime. Connect with participants 2019; https://www.turkprime.com/Service/ConnectWithParticipants.

- 29. Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Alley DE, Karlamangla A, Seeman T. Hispanic paradox in biological risk profiles. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1305–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jeong M, Zhang D, Morgan JC, et al. Similarities and differences in tobacco control research findings from convenience and probability samples. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(5):476–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Food and Drug Administration. Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; restrictions on the sale and distribution of tobacco products and required warning statements for tobacco products. Fed Regist. 2016;81:28973–29106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [computer program]. Version 3.4.3. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Generalized estimation equation solver [computer program]. Version 4.13-192015. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kennedy RD, Awopegba A, De León E, Cohen JE. Global approaches to regulating electronic cigarettes. Tob Control. 2017;26(4):440–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):788–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Soneji SS, Sung HY, Primack BA, Pierce JP, Sargent JD. Quantifying population-level health benefits and harms of e-cigarette use in the United States. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0193328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang JB, Olgin JE, Nah G, et al. Cigarette and e-cigarette dual use and risk of cardiopulmonary symptoms in the Health eHeart Study. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0198681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Noar SM, Kelley DE, Boynton MH, et al. Identifying principles for effective messages about chemicals in cigarette smoke. Prev Med. 2018;106:31–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roditis ML, Jones C, Dineva AP, Alexander TN. Lessons on addiction messages from “The Real Cost” campaign. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(2S1):S24–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huang J, Feng B, Weaver SR, Pechacek TF, Slovic P, Eriksen MP. Changing perceptions of harm of e-Cigarette vs Cigarette use among adults in 2 US National Surveys From 2012 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e191047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wackowski OA, Sontag JM, Hammond D, et al. The impact of e-cigarette warnings, warning themes and inclusion of relative harm statements on young adults’ e-cigarette perceptions and use intentions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(2):184–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yang B, Owusu D, Popova L. Testing messages about comparative risk of electronic cigarettes and combusted cigarettes. Tob Control. 2019;28(4):440–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Berinsky AJ, Huber GA, Lenz GS. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Polit Anal. 2012;20(3):351–368. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Weinberg JD, Freese J, McElhattan D. Comparing data characteristics and results of an online factorial survey between a population-based and a crowdsource-recruited sample. Sociol Sci. 2014;1:292–310. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.