Summary:

Recombinant immunotoxins (RITs) are genetically engineered proteins designed to kill cancer cells. The RIT HA22 contains the Fv portion of an anti-CD22 antibody fused to a 38 kDa fragment of Pseudomonas exotoxin A (PE38). As PE38 is a bacterial protein, patients frequently produce antibodies that neutralize its activity, preventing retreatment. We have earlier shown in mice that PE38 contains 7 major B-cell epitopes located in domains II and III of the protein. Here we present a new mutant RIT, HA22-LR-6X, in which we removed most B-cell epitopes by deleting domain II and mutating 6 residues in domain III. HA22-LR-6X is cytotoxic to several lymphoma cell lines, has very low nonspecific toxicity, and retains potent antitumor activity in mice with CA46 lymphomas. To assess its immunogenicity, we immunized 3 MHC-divergent strains of mice with 5 μg doses of HA22-LR-6X, and found that HA22-LR-6X elicited significantly lower antibody responses than HA22 or other mutant RITs with fewer epitopes removed. Furthermore, large (50 μg) doses of HA22-LR-6X induced markedly lower antibody responses than 5 μg of HA22, indicating that high doses can be administered with low immunogenicity. Our experiments show that we have correctly identified and removed B-cell epitopes from PE38, producing a highly active immunotoxin with low immunogenicity and low animal toxicity. Future studies will determine if these properties carry over to humans with cancer.

Keywords: HA22, BL22, deimmunization, protein engineering, B-cell epitopes

Recombinant immunotoxins (RITs) are anticancer agents composed of an antibody variable fragment (Fv) fused to a portion of a protein toxin.1,2 In our laboratory, we produce RITs by fusing the Fv of a cancer-specific antibody to a 38 kDa fragment of Pseudomonas exotoxin A (PE38). PE38 contains 2 major domains from exotoxin A: domain II (residues 253 to 364) and domain III (residues 395 to 613) and a small portion of subdomain Ib (residues 381 to 394). The RIT BL22 targets CD22-positive B-cell malignancies and has produced major therapeutic responses in drug resistant hairy cell leukemia with a side effects profile that supported continued development.3,4 One important reason for the clinical success of BL22 is that repeated doses can often be given without inducing neutralizing antibodies, because the immune system of these patients are suppressed by disease and chemotherapy. In contrast, the mesothelinspecific RIT, SS1P, has had modest success targeting solid tumors expressing mesothelin.5 Poor RIT tumor penetration and binding to shed antigen6,7 necessitate multiple treatment rounds. However, these patients have normal immune systems and rapidly form neutralizing antibodies, preventing retreatment.

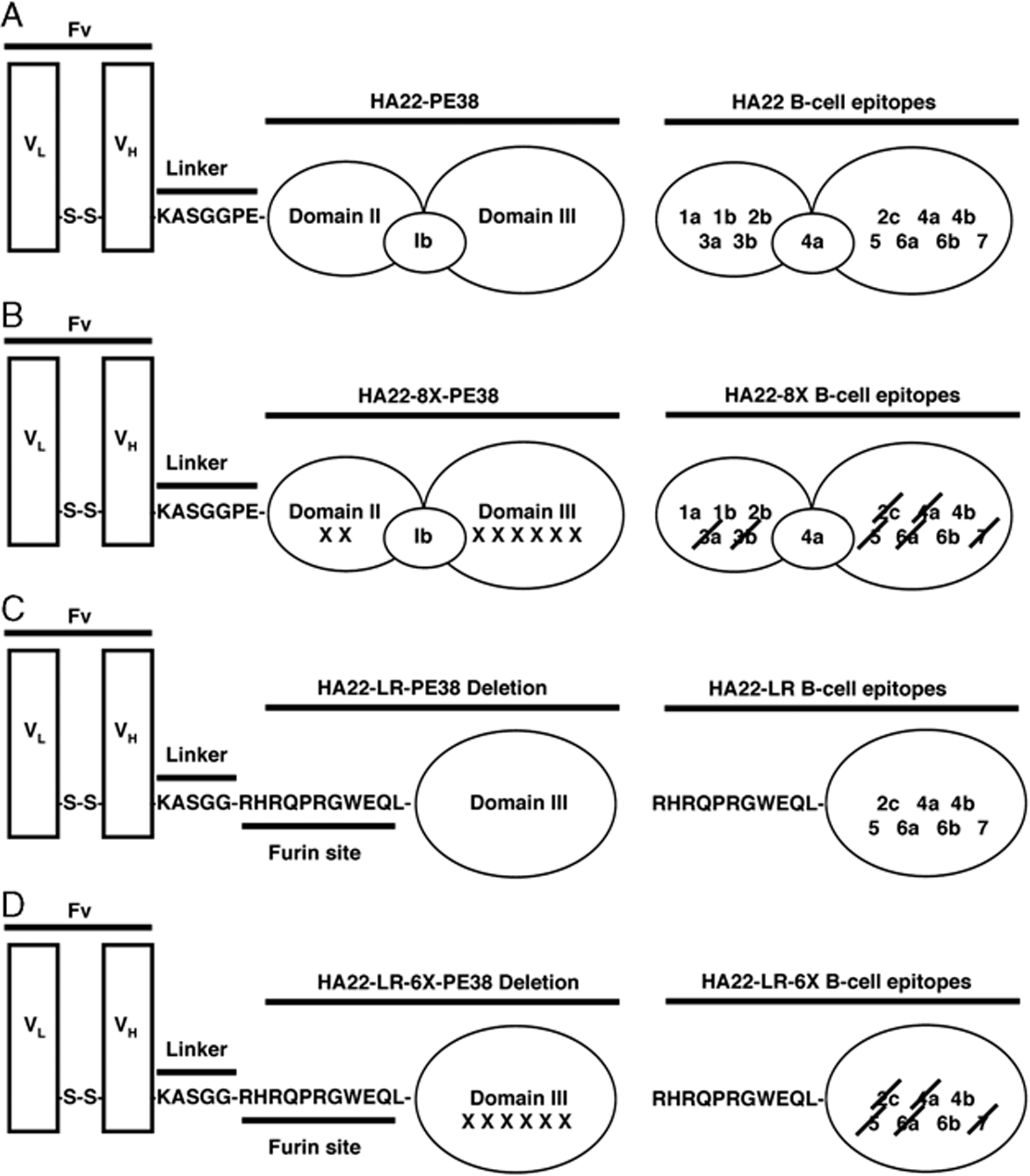

To design less immunogenic RITs, we generated a panel of PE38-specific mAbs to map the major mouse B-cell epitopes in PE38. We have shown that PE38 contains 7 major epitope groups that can be further divided into 12 subgroups.8 We have identified key amino acids in each epitope group by mutating bulky and highly exposed residues on the surface of PE38 to alanine, glycine, or serine, and shown that mAbs defining each epitope group no longer bind these mutant molecules.8,9 Using these data, we began to eliminate multiple epitopes by combining mutations into a single molecule. The location of each epitope group in PE38, and the point mutations used to eliminate them, are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1, respectively. The parental RIT, HA22, is an affinity-optimized variant of BL22 that contains all PE38 epitope groups (Fig. 1A).11,12 From this template we synthesized the variant RIT HA22–8X, in which we mutated 2 residues in domain II and 6 in domain III, for a total of 8 point mutations (Fig. 1B). Domain II point mutations Q332S and R313A were constructed to eliminate epitopes 1 and 3, respectively, but the Q332S mutation only partially abolishes antibody binding to epitope l. Domain III point mutations effectively target epitope 2c with the R467A mutation, epitope 5 with R490A, epitope 6a with R513A and E548S, and epitope 7 with K590S. The domain III point mutation R432G, however, does not fully abolish antibody binding to epitope 4a, because a portion of this discontinuous epitope is present in domain Ib (Table 1, Fig. 1B). Despite not removing all epitope groups, HA22–8X was found to be significantly less immunogenic than HA22 when given i.v. to mice, proving that elimination of B-cell epitopes is a promising approach to producing less immunogenic proteins.9

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of recombinant immunotoxins (RIT) design showing B-cell epitopes associated with each domain. Column 1 sshows the variable fragment (Fv), linker, and Pseudomonas exotoxin A (PE38) domains present in HA22 (A), HA22–8X (B), HA22-LR (C), and HA22-LR-6X (D). Column 2 is a model of PE38 domains with B-cell epitopes listed. For HA22–8X and HA22-LR-6X (B, D), B-cell epitopes that have been removed by mutation are crossed out. For HA22-LR and HA22-LR-6X (C, D) the domain II furin site is present.

TABLE 1.

Description of Parental and Mutant CD22-targeting RITs and Determined In Vitro Cytotoxic Activities on WSU, CA46, and Raji Cell Lines

| RIT | Mutation (Targeted Epitope Group) | Deletion* | Tested Cell Lines | IC50 (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA22 | — | — | wsu | 2.0 |

| CA46 | 0.33 | |||

| RAJI | 0.13 | |||

| HA22–8X | Q332S (1), R467A (2c), R313A (3), R432G (4a), R490A (5), R513A (6a), E548S (6a), K590S (7) | — | — | — |

| HA22-LR | — | Δ251–273 | WSU | 0.8 |

| Δ285–394 | CA46 | 0.3 | ||

| RAJI | 0.4 | |||

| HA22-LR-6X | R467A (2c), R432G (4a), R490A (5), | Δ251–273 | WSU | 0.8 |

| R513A (6a), E548S (6a), K590S (7) | Δ285–394 | CA46 | 0.4 | |

| RAJI | 0.3 |

PE38 in HA22 contains amino acids 251 to 364 and 381 to 613 of Pseudomonas exotoxin A numbered according to the crystal structure (Protein Data Bank, 1IKQ).10

RIT indicates recombinant immunotoxins.

Another approach we have taken to limit immunogenicity has been to design a RIT that is protease-resistant to diminish antigen processing.13 Immunotoxins containing PE38 were exposed to a series of lysosomal proteases followed by N-terminal sequencing of peptide products to identify cleavage sites.13 We found that protease sites were clustered in domains II and Ib, and we could remove these protease sensitive regions by deleting most of these domains to produce immunotoxin HA22-LR. As shown in Figure 1C, HA22-LR contains only the furin cleavage site of domain II, necessary for intracellular processing and transport of domain III into the cytosol.14–16 This deletion removes B-cell epitopes 1a, 1b, 2b, 3a, and 3b in domain II, and a portion of 4a in domain Ib. Thus, HA22-LR is not only deficient in protease sites but also deficient in 3 epitope subgroups (1a, 1b, 2b) still present in HA22–8X (Figs. 1B, C, Table 1). In addition, we found that HA22-LR was significantly less toxic to mice,13,17 enabling large doses to be administered and greatly increased antitumor activity achieved with no deleterious side effects.

In this study, we report on the properties of a new immunotoxin, HA22-LR-6X, in which we have combined the HA22-LR deletion (Fig. 1C) with the point mutations in domain III (Fig. 1B) to remove all domain II and Ib epitopes and the majority of domain III epitopes (Fig. 1D). We show that HA22-LR-6X has a further reduction in immunogenicity, retains low animal toxicity, and displays high antitumor activity at high doses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction, Expression, and Purification of RIT

HA22 and mutant RITs are composed of the heavy chain Fv fused to PE38 (VH-PE38) and disulfide-linked to the light chain Fv (VL). The expression plasmids for HA22 VH-PE38, HA22–8X VH-PE38, and VL have been described.9 The VH-PE38 chain of HA22-LR was generated after 2 cycles of site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange II, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to delete nucleotides corresponding to PE38 residues 251 to 273 and 285 to 394. The VH-PE chain of HA22-LR-6X was generated by excising the domain III fragment containing the 6X point mutations (PstI/EcoRI) from pRB1106 and placing the fragment between the same sites of the HA22-LR VH-PE38 chain. HA22-LR and HA22-LR-6X constructs were cloned into a chloramphenicol resistance plasmid, pRB98 (NdeI/EcoRI), for protein expression. All RITs were purified by a standard protocol established in our laboratory.18

Experimental Animals

Female Balb/c, C57BL/6J and A/J mice (6 to 8-wkold), female SCID mice (5 to 6-wk-old), and nude male mice, (5 to 6-wk-old) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) or Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) for immunization trials, anti-tumor assays, and toxicity studies, respectively. Animals were handled according to the National Institutes of Health guidelines approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Cancer Institute.

Nonspecific Mouse Toxicity

Male nude mice (18 to 22 g) were injected i.v. in the tail vein with HA22 (2.0 mg/kg) or HA22-LR-6X (2.5 and 5 mg/kg) in 0.2 mL PBS with 0.2% HSA. Mice were observed for several weeks for changes in health and mortality. In a separate experiment, a mouse from each treatment group was sacrificed 27 hours postinjection. Blood was collected and serum samples were analyzed for alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels (Ani Lytics, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). Livers were removed, fixed, and examined for changes in morphology.

Mouse Immunization Trials

Female Balb/c, C57BL/6, and A/J mice were immunized by i.p. injection with HA22 (5 μg/mouse), HA22–8X (5 μg/mouse), HA22-LR (5 or 50 μg/mouse), or HA22-LR-6X (5 or 50 μg/mouse) diluted in 200 uL of PBS with 0.2% mouse serum albumin. Mice received a booster injection every 2 weeks at the same dose for a total of 3 immunizations. Blood was collected 10 days after each immunization and serum used for ELISA and neutralization assays.

Immune Complex Capture (ICC) DELPHIA ELISA

An ICC ELISA was used to measure the relative amount of PE38-specific antibodies in serum. Microtiter plates (Maxisorp, Nalge Nunc, Rochester, NY) were coated with CD22-Fc (4 μg/mL in PBS) overnight at 4°C. Simultaneously, serum (diluted 1:250) from immunized mice was incubated with a corresponding RIT (2 mg/mL in blocking buffer; 25% DMEM, 5% FBS, 25 mM Hepes, 0.5% BSA, 0.1% sodium azide in PBS) in a 96-well round-bottom tissue culture plate. The CD22-Fc coated plates were washed twice with PBST and blocked for 1 hour (200 mL/well) at 25°C. The ELISA plate was washed twice with PBST and incubated with serum-RIT complexes (50 μL/well taken from the tissue culture plate) for 3 hours.

RIT-specific antibodies were detected with antimouse using a DELFIA fluorometric assay (Perkin-Elmer Life Science, Waltham, MA) as described.9

Statistical Analysis

A Mann-Whitney nonparametric method was used to compare 2 experimental groups in both the anti-tumor activity assay and the immunogenicity experiments. A P value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Design and Purification of a New RIT, HA22-LR-6X

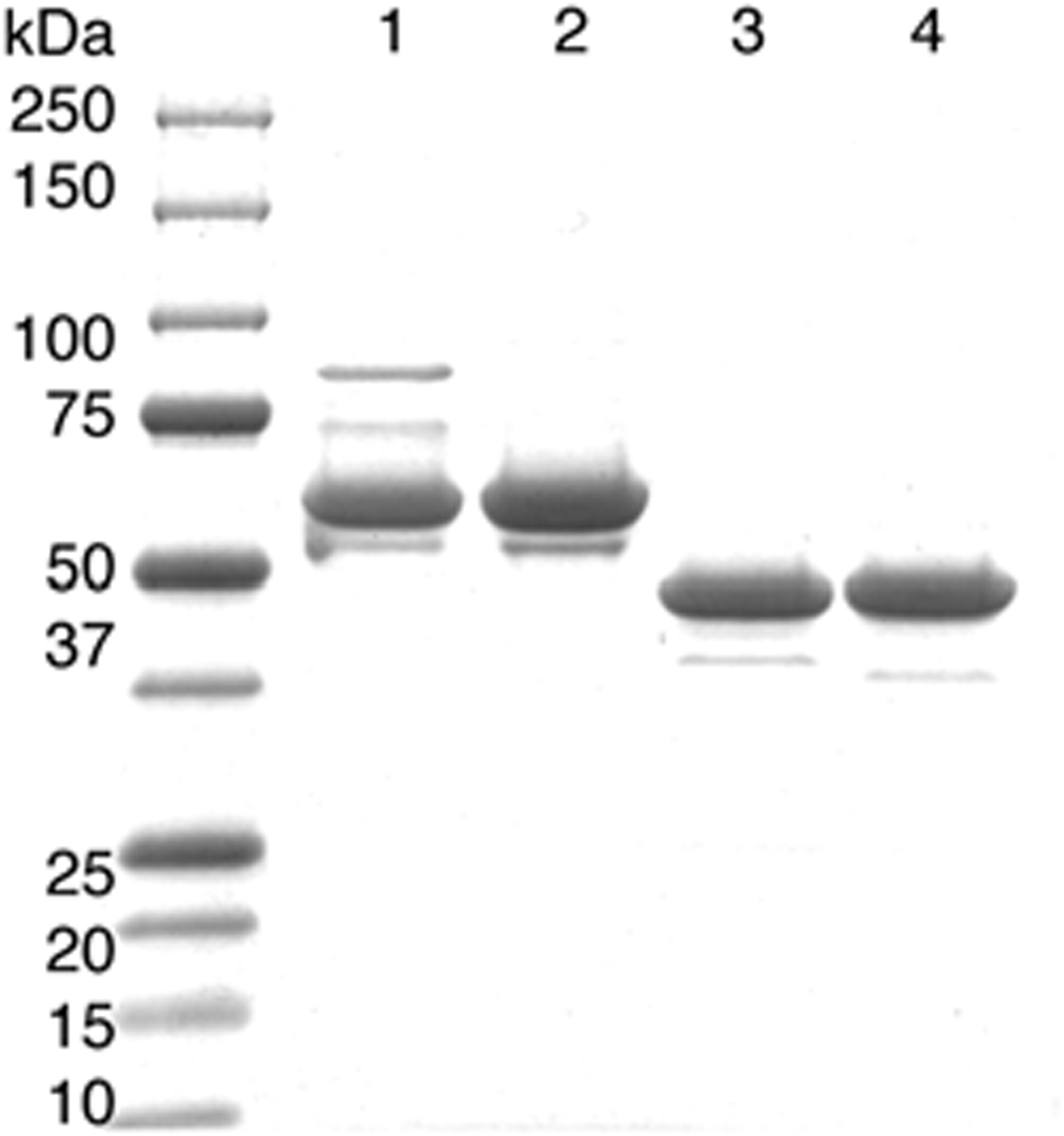

HA22-LR-6X has a deletion of residues 251 to 273 and 285 to 394 from PE38, and consists of the CD22-specific Fv attached to domain III by a short linker followed by a furin cleavage site (Fig. 1D). In addition, HA22-LR-6X has 6 point mutations (Table 1), which remove most B-cell epitopes present in domain III, with the exception of 4b and 6b (Fig. 1C). Table 1 contains information on the RITs described in this study, indicating residues mutated or deleted. These immunotoxins were purified to near homogeneity as described.18 After the final size exclusion purification step, we assessed the purity of the major monomer peak-containing fractions by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2). Under nonreducing conditions, purified HA22 and HA22–8X have an expected molecular weight of 63 kDa, and purified HA22-LR, and HA22-LR-6X have an expected molecular weight of 51 kDa. The endotoxin levels of each RIT were determined by using the Limulus amoebocyte lysate test and are<4 eu/mL (<1 ng/mL). In summary, the 4 RITs used in this study are highly purified monomers with low endotoxin levels and are suitable for animal studies.

FIGURE 2.

SDS-PAGE of purified recombinant immunotoxins (RIT). Twelve percent SDS-PAGE gel of purified 63 kDa HA22 (lane 1), 63 kDa HA22–8X (lane 2), 51 kDa HA22-LR (lane 3), and 51 kDa HA22-LR-6X (lane 4).

HA22-LR-6X Is Active In Vitro

Using the purified proteins, we carried out cytotoxicity assays13 and calculated the IC50s of HA22, HA22-LR, and HA22-LR-6X on Burkitt lymphoma cell lines Raji and CA46, and on the WSU acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line. HA22–8X has earlier been shown to have identical activity to HA22,9 and was not included in our evaluation here. For these cytotoxicity assays 104 cells were incubated with a dilution series of each RIT for 72 hours and cell viability was measured with a colorimetric WST-8 assay (Table 1). We found that HA22-LR and HA22-LR-6X have similar activity on CA46 cells, a 2-fold higher activity on WSU cells, and 3-fold lower activity on Raji cells when compared with HA22.

HA22-LR-6X Has Lower Nonspecific Toxicity in Mice Than HA22

We have shown that HA22-LR is less toxic to mice than HA22, with mice tolerating doses up to 20 mg/kg.13 To test nonspecific toxicity of HA22-LR-6X, we treated nude mice with a single dose at 2.5 mg/kg (~50 μg/mouse) and 5 mg/kg (~100 μg/mouse). As a positive control, we injected mice with a single dose of HA22 at 2.0 mg/kg (~40 μg). None of the HA22-LR-6X treated mice died (0/3 for both 50 and 100 mg groups) or seemed ill when followed for 2 weeks; while the HA22-treated mice (2/2) died within 48 hours. We also collected serum samples for AST and ALT analysis and removed and fixed livers from mice 27 hours after RIT treatment. There was no difference in AST and ALT serum levels between untreated mice (314 and 48 U/L, respectively) and mice treated with 50 or 100 μg of HA22-LR-6X (129 and 72 U/L, and 141 and 51 U/L, respectively), and livers seemed normal for both groups. In mice treated with 40 μg of HA22, the AST and ALT levels were markedly elevated (4850 and 4658 U/L, respectively) and the liver seemed hemorrhagic with distended gall bladder. We conclude that very high doses of HA22-LR-6X can be given safely to mice.

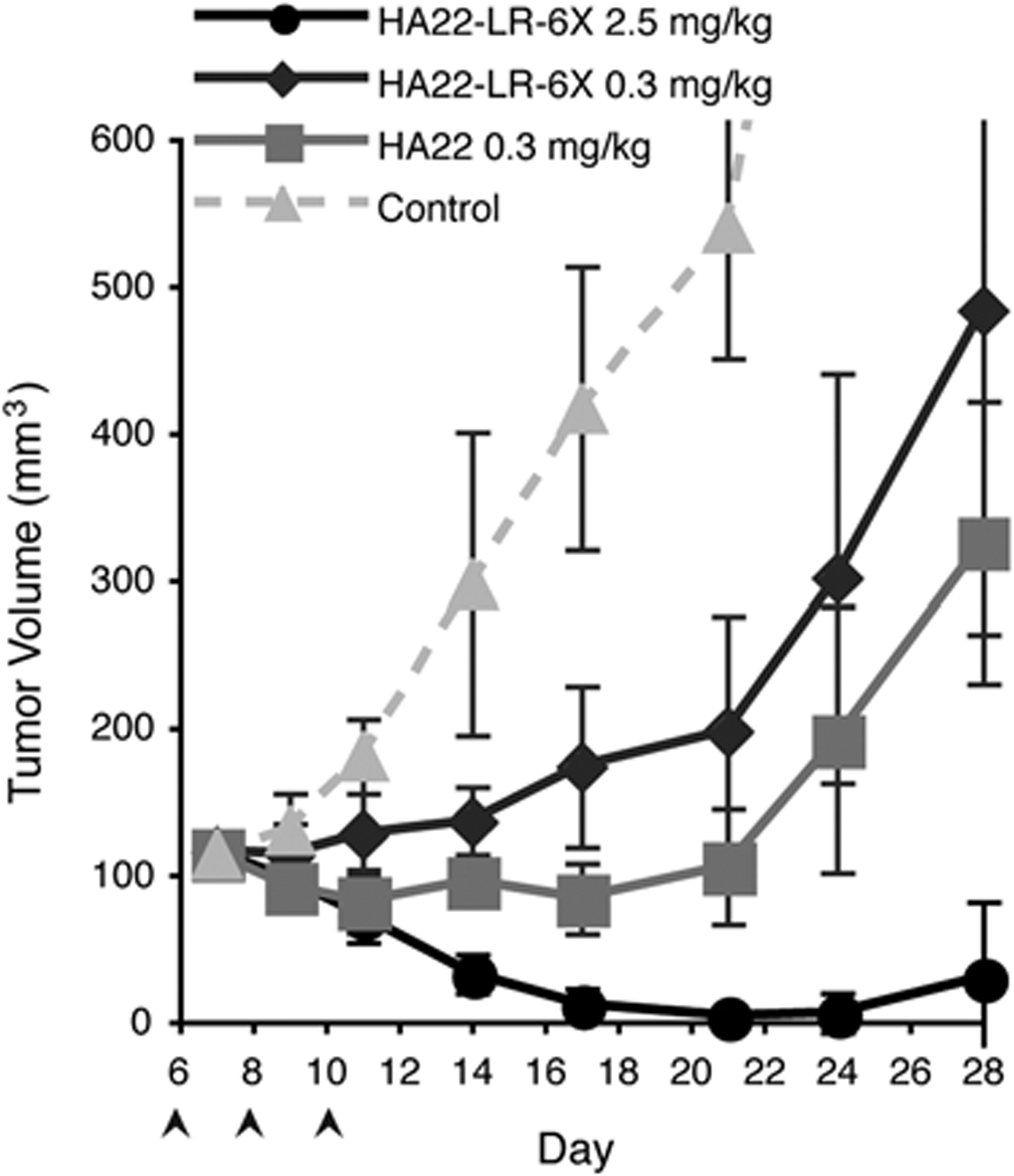

HA22-LR-6X Has Antitumor Activity in a Mouse Lymphoma Model

After establishing that HA22-LR-6X had low toxicity, we determined antitumor activity in a CA46 mouse xenograft lymphoma model.13 We implanted SCID mice with 1 × 107 CA46 cells, allowed the tumors to grow to 100 to 125 mm3 in size, and gave the mice 3 i.v. injections every other day of either HA22 or HA22-LR-6X (Fig. 3). We administered HA22 at 0.3 mg/kg (~6 μg/mouse), which is close to the maximum tolerated dose (MTD), or HA22-LR-6X at an equivalent dose of 0.3 mg/kg (~6 μg/mouse), or at a high dose of 2.5 mg/kg (~50 μg/mouse). At 0.3 mg/kg both RITs caused a cessation of tumor growth for about 10 days and then rapid growth resumed; although, HA22-LR-6X was slightly less active than HA22. At this dose of HA22, tumor regrowth is not the result of resistance caused by decreased CD22 expression, because repeat dosing has the same effect. Tumor regrowth is instead most likely owing to a residual population of cells not killed by immunotoxin treatment, and can be remedied by additional treatment cycles. In contrast, the antitumor effect of HA22-LR-6X given at 2.5 mg/kg was very pronounced compared with HA22 (P = 0.012), and at 28 days no tumor could be detected in 2 of the 5 treated mice. We did not test a higher dose of HA22-LR-6X. We conclude that HA22-LR-6X is highly active against CA46 tumors in mice even though an MTD was not reached.

FIGURE 3.

HA22-LR-6X has improved antitumor activity at a high dose. SCID mice were implanted with 106 CA46 cells on day 0 and tumors were allowed to reach approximately 125 mm3. At days 6, 8, and 10 mice were treated (arrows) with HA22 at 0.3 mg/kg (gray squares), or HA22-LR-6X at 0.3 mg/kg (dark gray diamonds) or at 2.5 mg/kg (black circles). PBS-control mice (dashed light gray triangles) were sacrificed when tumor burden reached 800 mm3 at day 24. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD with n = 5. By day 26 there were significant differences between HA22 (0.3 mg/kg) and HA22-LR-6X (2.5 mg/kg) (P < 0.05).

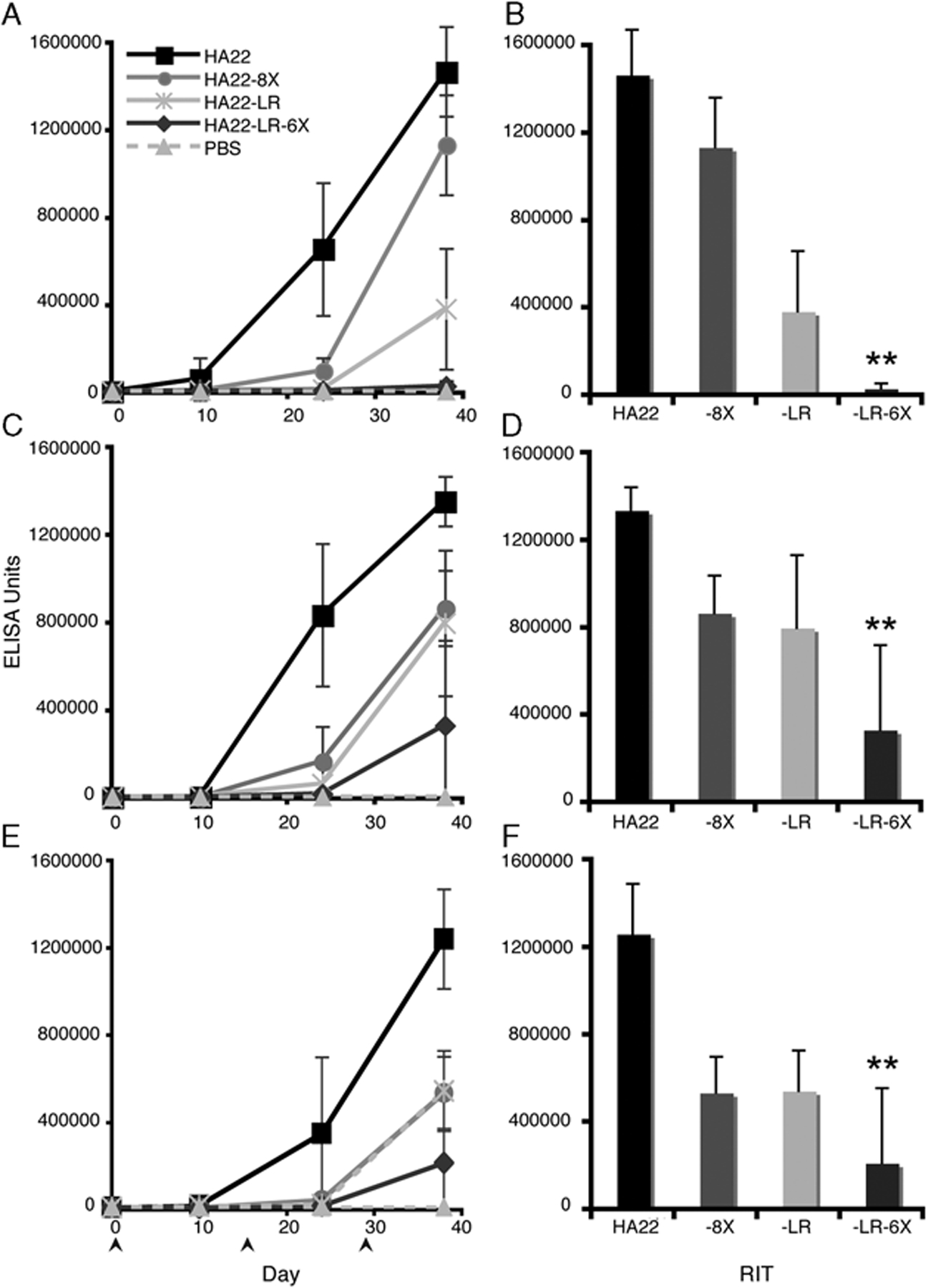

HA22-LR-6X Has Decreased Antibody Responses in 3 Strains of Mice

To determine antibody responses to the RITs, we immunized mice with 5 μg/mouse of immunotoxin every 14 days i.p. 3 times. We chose the i.p. route over the i.v. route because proteins given i.p. evoke higher antibody responses,19 allowing us to test our deimmunization strategy under more demanding conditions. We determined the relative antibody titer to each RIT by an ICC ELISA in which antibodies in the serum react in solution with conformational RIT epitopes. Fv binding to CD22 then captures RIT-antibody complexes and the amount of antibody bound to exotoxin A is detected (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Antibody responses are decreased in Balb/c, C57/BL6 and A/J mice immunized with a mutant recombinant immunotoxins (RIT). Balb/c (A, B), C57/BL6 mice (C, D), and A/J (E, F) mice were immunized i.p. on days 0, 14, 28 (bottom arrows) with 5 μg of HA22 (black squares), HA22–8X (gray circles), HA22-LR (light gray stars), or HA22-LR-6X (dark gray diamonds). Serum was collected on days 10, 24, and 38. Graphs A, C, and E show relative antibody responses to all antigens with a PBS control (dashed light gray triangles). Graphs B, D, and F compare mean RIT antibody responses among HA22, HA22–8X, HA22-LR, and HA22-LR-6X at day 38. Values are expressed as the mean ± SD with n = 10 (n = 5 for PBS mice). A star indicates that HA22-LR-6X-specific responses are significantly different from HA22, HA22–8X, and HA22-LR (P < 0.05).

In the first experiment (Fig. 4A) we immunized Balb/c (H2d) mice with HA22, HA22–8X, HA22-LR, or HA22-LR-6X. After 3 immunizations, HA22-specific responses are prominent, whereas HA22-LR-6X-specific responses are similar to PBS-treated mice levels. HA22–8X, earlier tested by i.v.,9 also gave a lower response than HA22 by i.p. On day 38 HA22-LR induced lower antibody responses than HA22 and HA22–8X, but still significantly higher than HA22-LR-6X (Fig. 4B). From these data, we conclude that HA22-LR-6X elicits significantly lower antibody responses than HA22 in Balb/c mice. Furthermore, HA22-LR-6X elicits lower antibody responses than HA22–8X or HA22-LR, indicating the combination of the LR deletion with domain III point mutations has a cumulative affect on decreasing RIT immunogenicity.

To determine the affect of MHC II haplotype on immunogenicity, we carried out immunization studies in 2 other strains of mice with different haplotypes, C57/BL6 (H2b) and A/J (H2a). In C57/BL6 mice the 3 mutant RITs induced lower antibody responses than HA22 after 3 immunizations (Fig. 4C). At day 38 HA22–8X and HA22-LR antibody responses were in the same range and HA22-LR-6X-specific responses were significantly lower (Fig. 4D). For A/J mice antibody responses to the mutant RITs after 3 immunizations were also below HA22-specific responses (Fig. 4E). At day 38 HA22-LR-6X-specific responses were significantly lower than HA22-specific responses and HA22–8X and HA22-LR (Fig. 4F). We conclude that HA22-LR-6X induces lower antibody responses than the other 3 RITs in all mice strains, regardless of MHC II haplotype. We attribute the low antibody response of HA22-LR-6X to the removal of both the protease sites and the B-cell epitopes from its parent molecule.

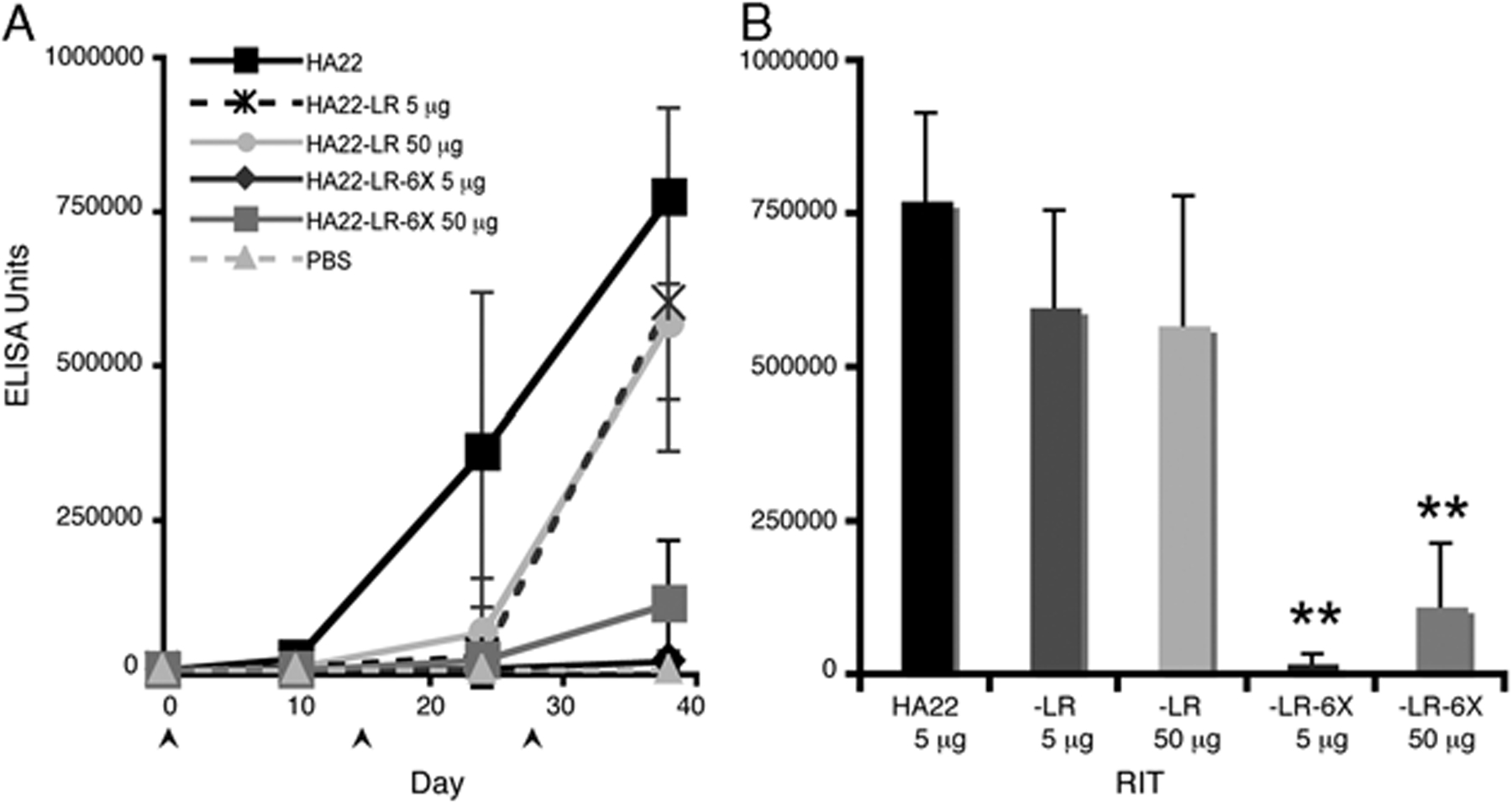

HA22-LR-6X Has Reduced Antibody Responses at High Doses

As HA22-LR-6X had lower activity than HA22 in vivo, treatment with higher doses will be needed to obtain the same antitumor effect. To determine the effect of higher doses on antibody responses and to evaluate the effect of domain III mutations, we immunized Balb/c mice 3 times i.p. with 5 or 50 μg of HA22-LR-6X and HA22-LR. For comparison purposes, we immunized mice with HA22 at 5 μg, but could not administer 50 μg owing to mouse mortality (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Antibody responses are decreased in Balb/c mice immunized with HA22-LR-6X at a higher dose. Balb/c mice were immunized i.p. with 5 μg of HA22 (black squares), 5 μg of HA22-LR (dashed dark gray stars), 50 μg of HA22-LR (light gray circles), 5 μg of HA22-LR-6X (dark gray diamonds), and 50 μg of HA22-LR-6X (gray squares). Serum was collected on days 10, 24, and 38. Graph A shows relative antibody responses to all antigens with a PBS control (dashed light gray triangles). Graph B compares mean recombinant immunotoxins (RIT) antibody responses among HA22, HA22-LR, and HA22-LR-6X at day 38. Values are expressed as the mean ± SD with n = 10 (n = 5 for PBS mice). A star indicates that HA22-LR-6X-specific responses are significantly different from HA22 and HA22-LR (P < 0.0001). There was a significant difference between HA22-LR-6X-specific responses at 5 and 50 μg (P = 0.001).

For HA22-LR-6X, the 10-fold increase in dose did not affect antibody responses after the second immunization on day 24 (Fig. 5A). On day 38 the antibody response to HA22-LR-6X at 50 μg had increased and was significantly higher than the 5 μg dose (Figs. 5A, B). When comparing HA22-LR-6X with HA22, the 50 μg dose did not increase HA22-LR-6X-specific responses to HA22 levels by day 38 (Fig. 5B). We conclude that after 3 immunizations in Balb/c mice, HA22-LR-6X at low and high doses induced lower antibody responses than HA22.

For HA22-LR, antibody responses were similar at both low and high doses after the third immunization and slightly below HA22-levels (Fig. 5A). When comparing these responses with HA22-LR-6X, we found that the 5 μg dose of HA22-LR-6X induced significantly lower antibody responses than HA22-LR at both 5 and 50 μg doses (Fig. 5B). Antibody responses to HA22-LR-6X at 50 μg were also significantly below HA22-LR responses at 5 and 50 μg doses (Fig. 5B). As the high dose of HA22-LR-6X induces lower antibody responses than the low dose of HA22-LR, we conclude that the removal of B-cell epitopes from domain III has a large affect on decreasing RIT immunogenicity.

Serum From HA22-LR-6X Immunized Mice Has Low Neutralization Activity

We conducted neutralization assays to determine if antisera from HA22-LR-6X treated mice were capable of neutralizing RIT activity. We again carried out cytotoxicity assays13 by incubating Raji cells with HA22 at 200 and 1000 ng/mL with or without serum from HA22-immunized or HA22-LR-6X-immunized Balb/c mice. Diluted serum (1:3) from HA22-immunized mice completely abolished HA22 activity when mixed with 200 ng/mL RIT, and inhibition was 93% at 1000 ng/mL RIT. In contrast, serum from HA22-LR-6X-immunized mice did not inhibit HA22 activity. We conclude that serum from HA22-immunized mice contains antibodies capable of inhibiting RIT activity and that serum from HA22-LR-6X immunized mice does not contain PE38 neutralizing antibodies.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we describe a new RIT, HA22-LR-6X, with high antitumor activity, very low animal toxicity and low immunogenicity. This new RIT has major deletions in domains II and Ib to remove B-cell epitopes and protease-sensitive regions and 6 point mutations in domain III to disrupt B-cell epitopes. Despite these significant changes to the PE38 backbone, we show that HA22-LR-6X has robust activity both in vitro and in vivo and can be safely given to mice at high doses. In immunization trials we show that an injection of 5 μg HA22-LR-6X induces lower antibody responses than 5 μg of HA22–8X or HA22-LR, indicating that 2 types of mutations can be combined to produce a molecule with even lower immunogenicity. In addition, we show that a 50 μg dose of HA22-LR-6X elicits an antibody response significantly below 5 μg of HA22, further supporting the notion that HA22-LR-6X could be given at higher doses with low immunogenicity.

To assess the therapeutic potential of HA22-LR-6X, we first determined its nonspecific toxicity in mice at high doses. RITs containing PE38 usually have an MTD near 0.3 mg/kg when given at multiple doses to mice (unpublished data), with higher doses resulting in liver damage and mortality.20 A single i.v. dose of HA22 has an LD50 of approximately 1.3 mg/kg11 and is uniformly fatal at 2 mg/kg.16 As earlier work has shown that HA22-LR can be given at a high dose without toxicity,16 we examined mice for mortality and also for liver toxicity after receiving 1 i.v. dose of HA22-LR-6X at 2.5 and 5.0 mg/kg (50 and 100 μg per 20 g, respectively). Treatment with HA22-LR-6X did not cause mortality or dramatic changes in liver enzyme levels at either of the doses. These data are in sharp contrast to the 2 mg/kg HA22-treated group in which all mice treated with HA22 were dead at 48 hours and had elevated levels of liver enzymes before death. These data show that HA22-LR-6X has low toxicity, indicating that it is safe to treat mice with high doses of HA22-LR-6X.

We took advantage of the low toxicity of HA22-LR-6X and treated tumors with a high dose of HA22-LR-6X in a CA46 mouse xenograft lymphoma model. After 3 doses with HA22-LR-6X at 2.5 mg/kg (50 μg/20 g mouse), we observed better antitumor activity by day 28, than with HA22 given near its MTD (Fig. 3). Although we did not directly compare HA22-LR-6X with HA22–8X in an antitumor assay, an earlier evaluation of HA22–8X in CA46 xenograft mice at its MTD of 0.4 mg/kg showed tumor regrowth at day 17,9 whereas the 2.5 mg/kg dose of HA22-LR-6X shown here repressed tumor growth until day 24 with 2 complete remissions. The antitumor effect of HA22-LR-6X is also consistent with the activity of HA22-LR at 2.5 mg/kg.13 However, the lower 0.3 mg/kg (6 μg/20 g mouse) dose of HA22-LR-6X is less effective than the same dose of HA22, which we attribute to the shorter half-life of HA22-LR-6X. HA22 has a molecular weight of 63.3 kDa, and has a half-life of approximately 15 minutes, whereas HA22-LR-6X is only 51.0 kDa in size with a half-life of 8 minutes (data not shown).13 This shorter half-life is probably the result of increased glomerular filtration of this protein in the mouse kidney.20,21 Potential strategies to increase the half-life of HA22-LR-6X include PEGylation and addition of an albumin-binding domain.

In earlier studies we evaluated antibody responses to HA22 and HA22–8X by giving each RIT to mice i.v. to mimic patient dosing. As we were concerned that differences in half-life between HA22 and the HA22-LR constructs16 could contribute to artificially low antibody responses, we immunized mice by i.p. injections to slow entry into the blood and compensate for differences in RIT pharmacokinetics. Antibody responses to HA22 were consistent in Balb/c, C57/BL6, and A/J mouse strains, with PE38-specific responses rapidly increasing after the second immunization (Fig. 4, first column). Mutant RITs showed different degrees of antibody responses, but were generally less immunogenic than HA22. We observed slight differences in the relative responses to mutant RITs among the 3 mouse strains at day 38 (Fig. 4, second column). HA22–8X-specific antibody responses were higher than those of HA22-LR in Balb/c mice after the third immunization, but were at similar response levels in C57/BL6 and A/J mouse strains. In addition, HA22-LR-6X responses were slightly lower in Balb/c mice than in the other 2 mouse strains. Despite these variations, HA22-LR-6X is consistently the least immunogenic of the tested RITs in all the mouse strains. These data suggest that antibody responses to HA22-LR-6X will be lower than HA22 regardless of MHC II haplotype. As HA22-LR-6X induced lower antibody responses than either HA22–8X or HA22-LR, this shows that the combination of the LR deletion with the HA22–8X domain III mutations had a cumulative effect on RIT-specific responses.

As our antitumor studies required more HA22-LR-6X to observe similar antitumor activity as HA22, we had to show that a high dose (50 μg) of HA22-LR-6X was less immunogenic (Fig. 5). We found that with HA22-LR or HA22-LR-6X increasing the dose 10-fold from 5 to 50 μg did not exceed the antibody response to HA22. HA22-LR-6X-specific responses at 50 μg were still below HA22-specific responses at 5 μg doses, supporting the notion that we could administer HA22-LR-6X at a high dose and expect low immunogenicity. Antibody responses induced by HA22-LR-6X at 50 μg were also lower than HA22-LR at 5 μg, which can be attributed to the additional domain III epitope groups in HA22-LR (Fig. 1). In addition to these epitope groups, we found that one of our mAbs against epitope 3B,8 IP44, binds to HA22-LR (unpublished data). IP44 reacts strongly with HA22, and its binding to PE38 is abolished by the R313A mutation in domain II of HA22–8X and also in HA22-LR-6X. As domain II is absent in HA22-LR, it is possible that IP44 also associates with domain III. This interaction could be occurring at a region that is mutated in HA22–8X and HA22-LR-6X, which would account for the inability of this antibody to bind domain III of these molecules. It is also noteworthy that the mAbs specific to epitope 4b (IP14 and IP86) both bind HA22-LR, but only IP14 binds to HA22-LR-6X. These additional epitopes may be contributing to the immunogenicity of HA22-LR and could account for the lower immunogenicity of HA22-LR-6X.

In addition to showing that HA22-LR-6X elicits low antibody responses in mice, we show that these antibodies do not inhibit HA22 activity on Raji cells in neutralization assays. As HA22-LR-6X induces a low level of antibodies, and these antibodies cannot neutralize HA22, there are probably few remaining B-cell epitopes in this molecule. Future work will focus on determining the contribution of T-cell epitopes to the immunogenicity of this molecule, which we have only indirectly addressed by removing protease-processing sites. The characteristics that distinguish HA22-LR-6X from former variants of HA22 are that (1) it can be given at higher doses than HA22–8X in mice owing to its lower nonspecific toxicity and that (2) it avoids the neutralizing antibodies generated by HA22–8X or HA22-LR owing to its lower immunogenicity. These properties suggest that we will see a significant clinical benefit when this mutation is incorporated into other RITs. Strong candidates for the LR-6X mutation could include the antimesothelin/PE38 RIT SS1P that elicits neutralizing antibodies in a large majority of patients after a single cycle of treatment, and may particularly benefit from the characteristics of this mutation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research and with a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement with MedImmune, LLC.

Footnotes

All authors have declared there are no financial conflicts of interest in regards to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pastan I, Hassan R, Fitzgerald DJ, et al. Immunotoxin therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pastan I, Hassan R, FitzGerald DJ, et al. Immunotoxin treatment of cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2007;58:221–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kreitman RJ, Wilson WH, Bergeron K, et al. Efficacy of the anti-CD22 recombinant immunotoxin BL22 in chemotherapy-resistant hairy-cell leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kreitman RJ, Squires DR, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al. Phase I trial of recombinant immunotoxin RFB4(dsFv)-PE38 (BL22) in patients with B-cell malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23: 6719–6729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassan R, Bullock S, Premkumar A, et al. Phase I study of SS1P, a recombinant anti-mesothelin immunotoxin given as a bolus I.V. infusion to patients with mesothelin-expressing mesothelioma, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5144–5149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Pastan I. High shed antigen levels within tumors: an additional barrier to immunoconjugate therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7981–7986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Xiang L, Hassan R, et al. Immunotoxin and Taxol synergy results from a decrease in shed mesothelin levels in the extracellular space of tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17099–17104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onda M, Nagata S, FitzGerald DJ, et al. Characterization of the B cell epitopes associated with a truncated form of Pseudomonas exotoxin (PE38) used to make immunotoxins for the treatment of cancer patients. J Immunol. 2006;177:8822–8834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onda M, Beers R, Xiang L, et al. An immunotoxin with greatly reduced immunogenicity by identification and removal of B cell epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11311–11316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allured VS, Collier RJ, Carroll SF, et al. Structure of exotoxin A of Pseudomonas aeruginosa at 3.0-Angstrom resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:1320–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bang S, Nagata S, Onda M, et al. HA22 (R490A) is a recombinant immunotoxin with increased antitumor activity without an increase in animal toxicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1545–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mansfield E, Chiron MF, Amlot P, et al. Recombinant RFB4 single-chain immunotoxin that is cytotoxic towards CD22-positive cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 1997;25:709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weldon JE, Xiang L, Chertov O, et al. A protease-resistant immunotoxin against CD22 with greatly increased activity against CLL and diminished animal toxicity. Blood. 2009;113:3792–3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogata M, Chaudhary VK, Pastan I, et al. Processing of Pseudomonas exotoxin by a cellular protease results in the generation of a 37,000-Da toxin fragment that is translocated to the cytosol. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20678–20685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiron MF, Fryling CM, FitzGerald DJ. Cleavage of Pseudomonas exotoxin and diphtheria toxin by a furin-like enzyme prepared from beef liver. J Biol Chem. 1994; 269:18167–18176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiron MF, Fryling CM, FitzGerald D. Furin-mediated cleavage of Pseudomonas exotoxin-derived chimeric toxins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31707–31711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onda M, Willingham M, Wang QC, et al. Inhibition of TNF-alpha produced by Kupffer cells protects against the nonspecific liver toxicity of immunotoxin anti-Tac(Fv)-PE38, LMB-2. J Immunol. 2000;165:7150–7156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pastan I, Beers R, Bera TK. Recombinant immunotoxins in the treatment of cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;248:503–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierce NF. Induction of optimal mucosal antibody responses: effects of age, immunization route(s), and dosing schedule in rats. Infect Immun. 1984;43:341–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliver C, Essner E. Protein transport in mouse kidney utilizing tyrosinase as an ultrastructural tracer. J Exp Med. 1972; 136:291–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maack T, Johnson V, Kau ST, et al. Renal filtration, transport, and metabolism of low-molecular-weight proteins: a review. Kidney Int. 1979;16:251–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]