The ILCOR COVID-19 consensus aimed to balance the benefits of early resuscitation with the potential for harm to care providers, stating, notably, that every emergency system should react according to its resources and its region’s evolving disease prevalence.1 The start and end of the lockdown period constituted critical time points when the rescue chain had to be accurately readjusted.

The effect of the COVID pandemic on the incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) in Paris has been previously described.2 Since the start of confinement in France (March 17, 2020), the Paris Fire Brigade prehospital emergency system was faced with the need to adapt its OHCA rescue chain. First, the dispatcher performed phone detection of OHCAs using the “hand over belly” technique, which showed its effectiveness in our system in the recent past.3 Indeed, insofar as this procedure kept the bystander away from the patient’s airway, it seemed quite safe. After asking the bystander to open the windows of the room to disperse a potential viral atmosphere, the dispatcher instructed him to perform chest compressions (CCs).4

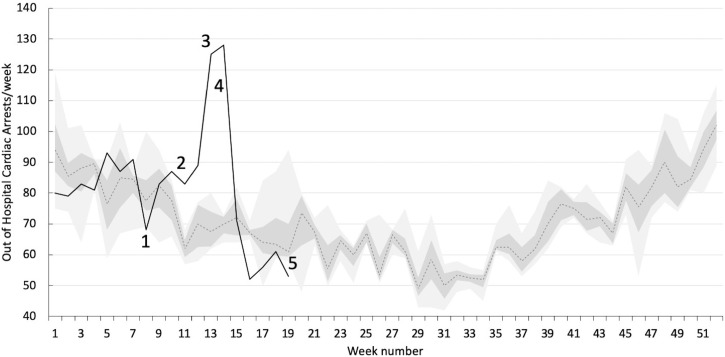

Second, the lockdown resulted in suspending our regional mobile lay-responder application, because mobile-responders had no personal protection equipment (PPE) at this time. Third, the AED-location map from this application failed to be helpful as most public places were closed. Fourth, the dispatch of the Basic Life Support (BLS) teams was limited to one crew per-patient instead of the two provided for in the pre-pandemic period, to limit rescuers’ viral exposure and to keep BLS teams available to treat the dramatically increased number of OHCAs that occurred during this period (Fig. 1 ).2

Fig. 1.

Number of weekly OHCAs treated by the BLS teams since January 1, 2020.

(These data have been previously published2).

The solid black line represents the number of OHCAs per week since January 1, 2020;

The grey dotted line reports the median number of OHCAs per week during the 2016–2019 period and the dark and light grey areas their corresponding interquartile and minimum-to-maximum ranges, respectively.

The numbers 1–5, along the solid black line, refer to the following events:

1. Brigade Headquarters instructions to the rescue workers to wear the Full Personal Protective Equipment.

2. Provisory suspension of the use of the mobile-responder app (Paris Lockdown).

3. Limitation to one BLS crew per-patient instead of the two provided for in the pre-pandemic period.

4. ILCOR Interim Guidance for Basic and Advanced Life Support in Patients with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19 (Originally published April 9, 2020).

5. Breaking out of confinement.

Before leaving the fire station, the BLS teams equipped themselves with gloves, N95 respirators, eye protection, gowns and overshoes, which took approximately one minute.5 Their response time was unchanged, because of reduced road traffic, with a median [interquartile range] drive time of 5 min 36 s [3 min 49 s–7 min 32 s] versus 5 min 10 s [3 min 33 s–7 min 29 s] before the lockdown period. Other BLS procedure adaptations were following ILCOR recommendations. As the Parisian system ensures the reinforcement of BLS teams by a prehospital emergency physician, the latter systematically employed a mechanical CC device to replace the manual CCs and limit the teams’ viral exposure. The physician performed orotracheal intubation wearing a hooded suit and ski mask and using video laryngoscopy.

Breaking out of confinement, which corresponds with the decrease in regional disease prevalence, requires restoring the lay-responder app and easing the BLS teams’ protection to save time in their CPR initiation. COVID’s decreasing prevalence makes it difficult for the dispatcher and the BLS team to differentiate COVID from non-COVID OHCAs instantly. Unfortunately, for some patients, this may result in inappropriate measures.

Finally, the emergency system’s responsiveness remains essential for a balanced adaptation of the rescue procedures to the pandemic’s evolution, any viral changes, and future scientific advances. In this context, the collection of accurate data remains more essential than ever.

Presentations

None.

Financial support, source of funding

No financial support. No source of funding.

This manuscript has not been published previously and is not under consideration elsewhere. All illustrations and figures in the manuscript are entirely original and do not require reprint permission.

Authors’ contributions

CD, FB, BF, RK KB and BP, conceived and structured the specific planification of the rescue chain.

DJ, CD and BP drafted the manuscript,

All authors contributed substantially to its revision.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Firefighters’ BLS teams for their unfailing determination and daily struggle in this war against disease.

References

- 1.Perkins G.D., Morley P.T., Nolan J.P. International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation: COVID-19 consensus on science, treatment recommendations and task force consensus on science, treatment recommendations and task force insights. Resuscitation. 2020;151:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marijon E., Karam K., Jost D. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the Covid 19 pandemic in Paris, France: a population-based, observational study. Lancet Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30117-1. Published online May 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Derkenne C., Jost D., Thabouillot O. Improving emergency call detection of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in the greater Paris area: efficiency of a global system with a new method of detection. Resuscitation. 2020;146:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hobday R.A., Dancer S.J. Roles of sunlight and natural ventilation for controlling infection: historical and current perspectives. J Hosp Infect. 2013;84:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abrahamson S.D., Canzian S., Brunet F. Using simulation for training and to change protocol during the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Crit Care. 2006;10:R3. doi: 10.1186/cc3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]