Abstract

Studies of eye movement have become an essential tool of basic neuroscience research. Measures of eye movement have been applied to higher brain functions such as cognition, social behavior, and higher‐level decision‐making. With the development of eye trackers, a growing body of research has described eye movements in relation to mental disorders, reporting that the basic oculomotor properties of patients with mental disorders differ from those of healthy controls. Using discrimination analysis, several independent research groups have used eye movements to differentiate patients with schizophrenia from a mixed population of patients and controls. Recently, in addition to traditional oculomotor measures, several new techniques have been applied to measure and analyze eye movement data. One research group investigated eye movements in relation to the risk of autism spectrum disorder several years prior to the emergence of verbal‐behavioral abnormalities. Research on eye movement in humans in social communication is therefore considered important, but has not been well explored. Since eye movement patterns vary between patients with mental disorders and healthy controls, it is necessary to collect a large amount of eye movement data from various populations and age groups. The application of eye trackers in the clinical setting could contribute to the early treatment of mental disorders.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, endophenotypes, eye movements, nonverbal communication, schizophrenia

Studies of eye movement have become an essential tool of basic neuroscience research. With the development of eye trackers, a growing body of research has described eye movements in relation to mental disorders.

![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

As has been postulated, eyes are windows to the brain as well as to the mind.1 Studies of eye movement have become an essential tool of basic neuroscience research. Almost every area of the brain plays some role in relation to ocular motor control.1 Eye movements are used to evaluate brain function in disorders affecting mostly the brain stem and cerebellum. Recently, measures of eye movements have been applied to higher brain functions such as cognition, social behavior, and higher‐level decision.1 Four noticeable features regarding the utility of eye movements have been observed. First, in many reports on schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), eye movement components are altered in the patient groups. Second, measures of eye movements may contribute to the early diagnosis of mental disorders.1, 2, 3 Third, eye movements may help group current diagnoses into new categories with or without certain types of eye control problems. Fourth, although social behavior including mutual gaze interaction is crucial for communication, eye movements in social situations have not been well explored. In this review, we briefly examine the current situation of eye tracking in mental disorders and discuss the possible application of eye trackers in the clinical setting.

2. METHODS

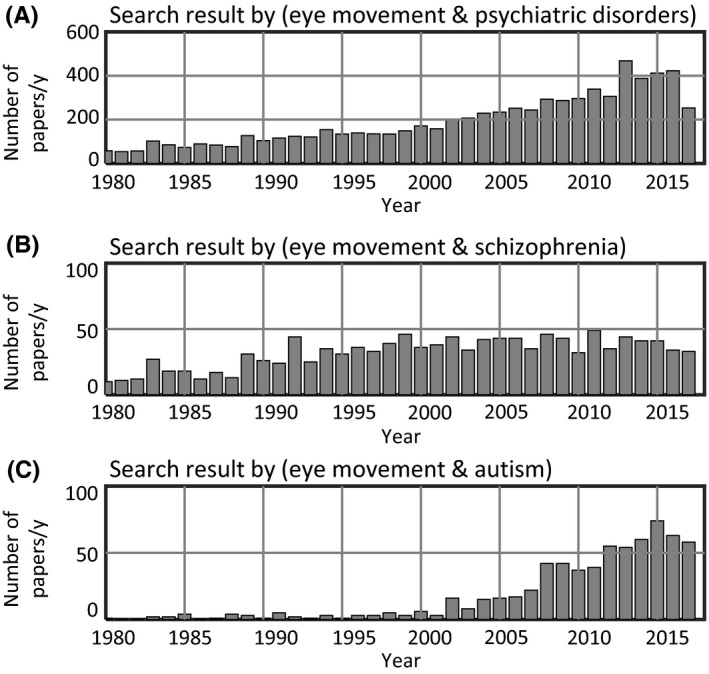

We performed a PubMed search for articles published between 1955 and 2017. We used (eye movement & psychiatric disorders), (eye movement & autism), and (eye movement & schizophrenia) as key words. About 90% of the initial search results for (eye movement & psychiatric disorders) were published after 1980; therefore, we examined studies from this period in regard to the following five aspects: (a) use of basic oculomotor movement measures; (b) introduction of a new method for measuring eye movements and/or conducting data analysis; (c) intention to perform a discrimination analysis of patients and controls from a mixed population; (d) provision of new information regarding measurements and data analysis; and (e) discussions regarding the possible advantages of using eye trackers in the clinical setting. All evaluations were conducted carefully while taking the number of patients and controls described in each report into account.

3. RESULTS

Figure 1 shows the results of the PubMed literature search. As listed in Table 1, eye movements serve as useful biomarkers in various types of psychiatric and cognitive disorders. There is a large variety of tests using eye trackers. Part of the reason for this variation is the different types of images shown on the monitor. The other part of the reason is the data analysis. In some studies,4 the analyzed data were simply the density of the gaze point in a picture, while in others, a temporal analysis of eye movement was conducted.5 A few studies included additional interpretations of eye movement data, such as a discrimination analysis of patients5 and an interpretation of eye movement in combination with the participant's genetic background.2

Figure 1.

Numbers of reported papers concerning eye movements and mental disorders. Since 1980, research examining the association between eye movements and mental disorders have been increasing. In patients with autism spectrum disorder, search results using the keyword “autism” have been increasing since the beginning of the twenty‐first century. (A–C) Data were obtained from a search of PubMed using the keywords denoted in the title for each graph

Table 1.

Examples of eye movement research involving individuals with various mental disorders and healthy controls

| Study | Subject | Type of eye tracker | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original articles | |||

| Kojima et al4 | SCZ | Display type | When viewing geometric figures, the patient group had fewer eye fixations |

| Takarae et al22 | ASD | Display type | Comparison of pursuit eye movements between patients with high‐functioning autism and healthy controls |

| Nakano et al39 | ASD | Display type | Examined interpersonal synchrony using eye blinks |

| Matsumoto et al40 | Parkinson's disease | Display type | When viewing still images, the scanned area was smaller in patients with Parkinson's disease |

| Benson et al13 | SCZ | Display type | Discrimination analysis of schizophrenia cases and controls with high accuracy; application of a neural network model |

| Jones et al21 | ASD (infants) | Display type | Longitudinal study of infants. Infants later diagnosed with ASD exhibited a mean decline in eye fixation |

| Wang et al23 | ASD | Display type | Used a saliency model for quantification of visual attention in patients with ASD and matched controls |

| Fujioka et al5 | ASD | Display type | Percentage of eye fixation time was depicted in movies such as eyes and mouth in human face movies, upright and inverted biological motion |

| Constantino et al2 | ASD (infants) | Display type | Examined twin‐twin concordance of monozygotes and dizygotes. Variation in viewing of social scenes was strongly influenced by genetic factors. Social visual engagement was impaired in children with ASD |

| Morita et al16 | SCZ | Display type | Linear classifier differentiated cases from controls. Medication affected eye movement |

| Sumner et al28 | DCD (not comorbid with another diagnosis) | Display type | Low‐level oculomotor processes appear intact in children with DCD. Top‐down cognitive control of eye movement was difficult in children with DCD |

| Reviews | |||

| Sweeney et al22 | ASD, ADHD, Tourette's syndrome | Display type | Emphasis on visually guided saccade, antisaccade, and memory‐guided saccade tasks |

| Karatekin3 | Various disorders, children | Multiple | Thorough review of the history of eye tracking studies. Some limitations of eye tracking are pointed out |

| Rommelse et al24 | ADHD, ASD, SLD, SCZ, OCD | Display type | Thorough review of eye movements in mental disorders during childhood and adolescence |

| Schilbach33 | Various disorders and healthy subjects | Multiple | Review of reciprocal and social gaze, including various setups for measurements |

| Thakkar et al12 | Various disorders | Display type | Focused on the failure to predict sensory consequences of one's own actions and psychosis |

ADHD, attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; DCD, developmental coordination disorder; OCD, obsessive‐compulsive disorder; SCZ, schizophrenia; SLD, specific learning disorder.

3.1. Eye movements in schizophrenia

The first study of eye movements in schizophrenia was published in the early 1900s.3 Since then, numerous studies have investigated eye movements in schizophrenia (Figure 1B).3, 6, 7 Strong evidence of abnormal scanning patterns have been reported among patients with schizophrenia.3, 6, 7 The study of exploratory eye movements4, 6 has been the focus of large‐scale research on scanning patterns in schizophrenia. Another form of eye movements called pursuit (tracking movements of the eyes toward the moving target) was found to be abnormal in some schizophrenic patients.3, 8, 9, 10, 11 Saccade, a rapid type of eye movement, has also been reported to differ in such patients compared with healthy controls.3, 12

Using a combination of these differences, Benson et al13 conducted a discrimination analysis of schizophrenia. They used a neural network model for classification that differentiated patients and controls from a mixed population. Another independent research group conducted a discrimination analysis of schizophrenia with a linear classifier.14 In both these reports, the accuracy of the discrimination analysis was 80% or higher; however, this may have been affected by the optimistic nature of their classifier.15

One important factor concerning schizophrenia is the effect of antipsychotic agents.16 The effect of dopamine blockade associated with antipsychotic agents is known to affect muscle movements, causing extrapyramidal symptoms such as parkinsonism, dystonia, and dyskinesia. Although eye movement has been reported to be significantly related to chlorpromazine‐equivalent doses of antipsychotic agents,16, 17 the antipsychotic effects of muscular abnormalities may vary depending on the individual. Antipsychotic therapy is commonly used in the treatment of schizophrenia, and the daily antipsychotic dose has been reported to have significant positive and negative associations with left globus pallidus volume and right hippocampus volume, respectively.18 Therefore, the effect of antipsychotic agents on eye movement must be carefully evaluated. Further research is needed to clarify the exact role of antipsychotic agents on eye movement.

3.2. Eye movements in ASD

Eye movement research in ASD has increased sharply in the twenty‐first century (Figure 1C). Among mental disorders, ASD is distinctive because its diagnosis is based on early childhood behavior.19 It is hard to obtain verbal‐behavioral information from a child during the limited time of a hospital visit. In 2015, a research group described a novel early detection method that used eye movements20 to assess the risk of developing ASD several years prior to verbal‐behavioral abnormalities. Detection methods using an eye tracker can assist clinicians in early identification of ASD. It is worth noting that 2‐ to 6‐month‐old infants who were later diagnosed with autism initially moved their eyes in a way that was indistinguishable from healthy controls; however, their eye movements declined over this period.21 This decline occurred in a narrow developmental time window. The research group recently published a paper on the social gaze of infants, reporting that eye movement traits have a genetic component.2 This finding is consistent with the strong tendency of heritability in autism.2 The gaze deficit in social contexts may begin as a neurological sign of their genetic background.

The results regarding ASD in early childhood are adequately consistent and sufficient for a possible diagnosis prior to the emergence of the behavioral characteristics applied as diagnostic criteria. It may therefore be possible to use eye trackers in screening for ASD in children who are amenable to early treatment. Measurement using eye trackers is a safe and noninvasive method for examining childhood development that may help examiners identify early signs of ASD in tandem with information from parents and caregivers.

As stated above, ASD is diagnosed in early childhood,19 but the majority of research experiments involving eye movement has been conducted in adults or adolescents.5, 22, 23 Some reports have described oculomotor behavior in school‐age children with ASD and compared it with age‐matched controls.3, 24 The results in those reports are not as prominent as those reported in studies on schizophrenia. In many of these published reports, group differences were found between participants with ASD and healthy controls; however, these are not without major discrepancies.3, 24, 25 This may be partly because there were often less than 20 participants with ASD in each study, so some of the results may not accurately reflect the total ASD population.

In 2016, a study group conducted a discrimination analysis using an eye tracker on adolescents and adults with ASD.5 They measured the eye movements of 26 ASD patients and 35 age‐matched controls and differentiated between both groups efficiently. Wang et al23 found atypical visual attention in people with ASD using a saliency map, which is a form of image processing that uses human vision as a model, with a dataset of 700 pictures of natural scenes. These two studies utilized high‐context images (such as faces and multiple people in a single image) and low‐context images (such as geometrical shapes and letters). The key feature of eye tracking in ASD is its ability to compare eye movements between two different image contexts and incorporate them into the analysis.

In regard to the specificity and overlap of eye movement abnormalities found across mental disorders,24 eye movements may help subdivide current diagnoses into subpopulations with or without a certain type of eye control problem. ASD is occasionally associated with intellectual disabilities, learning disorders, and attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), so study populations should contain multiple subgroups with or without comorbid disorders. For example, hyperactivity is relatively common during childhood in high‐functioning ASD, and children with high‐functioning ASD are often hyperactive.26 This comorbidity may cause the heterogeneity of eye movements in ASD. In people with ADHD, altered eye movements have been reported by a number of research groups.3, 24 In addition, saccade timing has been shown to be altered in people with ADHD.24

The discrepancies between the published papers on ASD3, 24, 25 may reflect the heterogeneity of the patients in each report. Therefore, subtype‐specific descriptions of eye behavior in people with ASD may be important for better understanding of its association with eye movements.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Recent developments in eye trackers

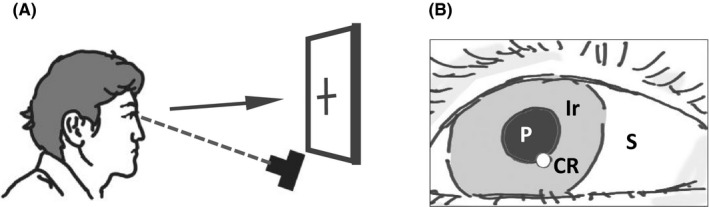

The history of eye tracker hardware has been described in several studies.3, 27 In 1991, a US company, SR Research, released a prototypical eye tracker. In 2001, another leading company, Tobii Technology, was founded in Sweden. In the twenty‐first century, the number of eye tracker manufacturers has been increasing with advances in the field. This increase in the number of manufacturers has coincided with the increase in the number of published papers (Figure 1). The most widely used method of estimating gaze using an eye tracker is based on the pupil‐corneal reflection technique,27 in which a camera captures time‐lapse images of the eye under appropriate illumination (Figure 2A). The positional data of parts of the eye (Figure 2B) are acquired and converted to indicate the geometrical location of the gaze on a monitor.

Figure 2.

Measurement of gaze by camera images of an eye. A, Schematic illustration showing how eye movements are measured with a camera. The arrow indicates the direction of gaze when a person looks at an object. B, In many eye trackers, the images of the eye are used to analyze the pupil (P) and corneal reflection (CR). Then, the geometrical position of the gaze is calculated from the P and CR positions. Since the iris (Ir) is more reflective to infrared than to visible light, infrared is often used as illumination. S, sclera

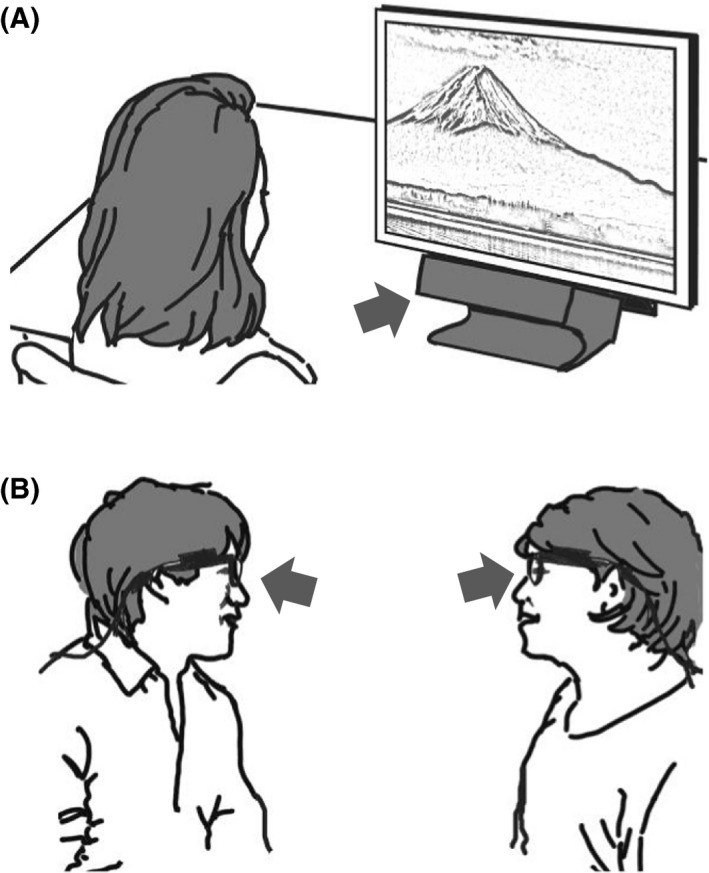

In the literature, the majority of the research has been conducted with the images shown on a display (Figure 3A). Typically, participants have been asked to sit on a chair and look at a visual stimulus on a monitor that includes graphical images, daily objects, faces, and scenes. Sometimes, participants are asked to follow a moving target. A setup such as that shown in Figure 3A provides easier control of spatial conditions with limited head movement. Usually, basic oculomotor behavior and eye movements have been measured by having a person look at a monitor screen. In the setup shown in Figure 3B, the gaze of two persons can be simultaneously monitored using eyeglasses equipped with an eye tracker. Although the interaction in terms of gaze between the two subjects can be monitored in this setup, the data analysis is more complicated than that for the setup shown in Figure 3A because it involves more variables and additional steps of analysis. Head movement is extensive and should be considered in the setup shown in Figure 3B.

Figure 3.

Two representative modes of experiments. A, In the display mode, an image or movie is shown on a monitor, and the participant is asked to look at it. B, Dual eye tracking: using a wearable eye camera, it is possible to monitor the gaze in social communication. The arrows indicate the possible position of cameras to capture eye movements

Traditionally, basic oculomotor measures consist of those from three eye movement types: fixations, saccades, and smooth pursuit.3, 28 Fixation centers the eyes on a stationary target; saccade is rapid eye movement between fixations, and smooth pursuit is seen when a person is tracking a moving target. In healthy persons, personal differences in oculomotor behavior are observed when looking at a monitor.29, 30 Differences in eye movements in healthy individuals are referred as their “oculomotor signature.”31 Variations in gaze patterns during face‐to‐face communication have also recently been described.32

4.2. Role of eye movements in social interaction

Despite the development of eye trackers, it remains unclear why eye‐to‐eye contact is necessary in communication. A situation in which two individuals are looking at each other is referred to as “mutual gaze”.32 Mutual gaze has a large impact on cognition and emotion,33 and the information obtained from another person's eyes is essential for mutual interaction.34 Extensive analysis conducted to date has yet to elucidate the mechanism that underlies this phenomenon. This may be partly because individual differences in gaze patterns are substantial.32 Everyone has a unique eye movement “fingerprint” when having a conversation.32 If someone has a defect in their eye movement, it is likely to affect how well they understand the behaviors of others, which can cause difficulties in his/her social life. Eye movement is among the endophenotypes necessary for a better understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms underlying mental disorders.

Genetic factors also play a substantial role in the etiology of mental disorders.9, 35, 36, 37 It has been suggested that ASD and schizophrenia share common biological pathways based on the recent genomic studies.38 Several groups have examined heritability estimates of eye movement phenotypes in patients with schizophrenia.8, 35 In those studies, two eye movement tasks were associated with moderate to high heritability.8, 35 Ladea and Prelipceanu9 concluded that such eye movement tasks are insufficient as diagnostic tests for schizophrenia. This is partly because the abnormalities observed in the eye movement tasks were frequently found in the patients’ unaffected relatives,8, 35 as well as in a minor population of healthy controls.9 However, eye movement tasks may be effective to test for biological markers of the associated risk of developing schizophrenia.9 Participating in a test involving such tasks may increase the chance of receiving an early intervention.

The application of eye trackers in the clinical setting to screen for mental disorders seems promising. At the same time, eye movement patterns vary considerably among both patients and healthy controls. Therefore, future studies should include larger numbers of eye movement examples from various populations and age groups. As reported in the case of ASD,2, 21 the longitudinal design of eye movement research could help achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between eye movements and mental disorders.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. N. Ozaki has received research support or speakers’ honoraria from or has served as a consultant to Astellas, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mochida, MSD, Nihon Medi‐Physics, Novartis, Ono, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Takeda, Taisho, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Tsumura, and KAITEKI. The remaining author have no conflict of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

E.S. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All other authors contributed to the data interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript.

DATA REPOSITORY

Supplementary material for figure 1 can be found in timeline.xlsx.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Drs T. Koike and N. Sadato for their helpful discussions. This research was supported by AMED under grant No. JP18dm0207005, JSPS KAKENHI grant No. 26461778, and a Research Fellowship by the Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders.

Shishido E, Ogawa S, Miyata S, Yamamoto M, Inada T, Ozaki N. Application of eye trackers for understanding mental disorders: Cases for schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2019;39:72–77. 10.1002/npr2.12046

REFERENCES

- 1. Shaikh AG, Zee DS. Eye movement research in the twenty‐first century‐a window to the brain, mind, and more. Cerebellum. 2017;17:252–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Constantino JN, Kennon‐McGill S, Weichselbaum C, et al. Infant viewing of social scenes is under genetic control and is atypical in autism. Nature. 2017;547:340–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Karatekin C. Eye tracking studies of normative and atypical development. Dev Rev. 2007;27:283–348. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kojima T, Matsushima E, Ando K, et al. Exploratory eye movements and neuropsychological tests in schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18:85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fujioka T, Inohara K, Okamoto Y, et al. Gazefinder as a clinical supplementary tool for discriminating between autism spectrum disorder and typical development in male adolescents and adults. Mol Autism. 2016;7:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kojima T, Matsushima E, Ohta K, et al. Stability of exploratory eye movements as a marker of schizophrenia–a WHO multi‐center study. World Health Organization. Schizophr Res. 2001;52:203– 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matsushima E, Kojima T, Ohta K, et al. Exploratory eye movement dysfunctions in patients with schizophrenia: possibility as a discriminator for schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32:289–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thaker GK. Neurophysiological endophenotypes across bipolar and schizophrenia psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:760–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ladea M, Prelipceanu D. Markers of vulnerability in schizophrenia. J Med Life. 2009;2:155–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moates AF, Ivleva EI, O'Neill HB, et al. Predictive pursuit association with deficits in working memory in psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:752–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ivleva EI, Moates AF, Hamm JP, et al. Smooth pursuit eye movement, prepulse inhibition, and auditory paired stimuli processing endophenotypes across the schizophrenia‐bipolar disorder psychosis dimension. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:642–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thakkar KN, Diwadkar VA, Rolfs M. Oculomotor prediction: a window into the psychotic mind. Trends Cogn Sci. 2017;21:344–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Benson PJ, Beedie SA, Shephard E, Giegling I, Rujescu D, St CD. Simple viewing tests can detect eye movement abnormalities that distinguish schizophrenia cases from controls with exceptional accuracy. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:716–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miura K, Hashimoto R, Fujimoto M, et al. An integrated eye movement score as a neurophysiological marker of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2014;160:228–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kuhn M, Johnson K. Applied predictive modeling. New York, NY: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morita K, Miura K, Fujimoto M, et al. Eye movement as a biomarker of schizophrenia: using an integrated eye movement score. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;71:104–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Inada T, Inagaki A. Psychotropic dose equivalence in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;69:440–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hashimoto N, Ito YM, Okada N, et al. The effect of duration of illness and antipsychotics on subcortical volumes in schizophrenia: analysis of 778 subjects. Neuroimage Clin. 2018;17:563–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Klin A. A new way to diagnose autism. TED Conference 2015. [Cited 2018 Aug 27] Available from https://www.ted.com/talks/ami_klin_a_new_way_to_diagnose_autism. Accessed 2018 Dec 26.

- 21. Jones W, Klin A. Attention to eyes is present but in decline in 2‐6‐month‐old infants later diagnosed with autism. Nature. 2013;504:427–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sweeney JA, Takarae Y, Macmillan C, Luna B, Minshew NJ. Eye movements in neurodevelopmental disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang S, Jiang M, Duchesne XM, et al. Atypical visual saliency in autism spectrum disorder quantified through model‐based eye tracking. Neuron. 2015;88:604–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rommelse NN, Van der Stigchel S, Sergeant JA. A review on eye movement studies in childhood and adolescent psychiatry. Brain Cogn. 2008;68:391–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schmitt LM, Cook EH, Sweeney JA, Mosconi MW. Saccadic eye movement abnormalities in autism spectrum disorder indicate dysfunctions in cerebellum and brainstem. Mol Autism. 2014;5:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Andersen PN, Hovik KT, Skogli EW, Egeland J, Oie M. Symptoms of ADHD in children with high‐functioning autism are related to impaired verbal working memory and verbal delayed recall. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holmqvist K, Marcus N, Anderson R, Dewhurst R, Jarodzka H, Weijer J. Eye tracking: a comprehensive guide to methods and measures. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sumner E, Hutton SB, Kuhn G, Hill EL. Oculomotor atypicalities in developmental coordination disorder. Dev Sci. 2018;21:e12501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dorr M, Martinetz T, Gegenfurtner KR, Barth E. Variability of eye movements when viewing dynamic natural scenes. J Vis. 2010;10:28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Castelhano MS, Henderson JM. Stable individual differences across images in human saccadic eye movements. Can J Exp Psychol. 2008;62:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bargary G, Bosten JM, Goodbourn PT, Lawrance‐Owen AJ, Hogg RE, Mollon JD. Individual differences in human eye movements: an oculomotor signature? Vision Res. 2017;141:157–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rogers SL, Speelman CP, Guidetti O, Longmuir M. Using dual eye tracking to uncover personal gaze patterns during social interaction. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schilbach L. Eye to eye, face to face and brain to brain: novel approaches to study the behavioral dynamics and neural mechanisms of social interactions. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2015;3:130–5. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Koike T, Tanabe HC, Sadato N. Hyperscanning neuroimaging technique to reveal the “two‐in‐one” system in social interactions. Neurosci Res. 2015;90:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Greenwood TA, Braff DL, Light GA, et al. Initial heritability analyses of endophenotypic measures for schizophrenia ‐ the consortium on the genetics of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1242–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shishido E, Aleksic B, Ozaki N. Copy‐number variation in the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;68:85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kushima I, Aleksic B, Nakatochi M, et al. High‐resolution copy number variation analysis of schizophrenia in Japan. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:430–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kushima I, Aleksic B, Nakatochi M, et al. Comparative analyses of copy‐number variation in autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia reveal etiological overlap and biological insights. Cell Rep. 2018;24:2838–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nakano T, Kato N, Kitazawa S. Lack of eyeblink entrainments in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:2784–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Matsumoto H, Terao Y, Furubayashi T, et al. Small saccades restrict visual scanning area in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26:1619–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials