Abstract

Objectives

To examine patterns of use of end-of-life care in patients receiving treatment at a large, urban safety-net hospital from 2000 to 2010.

Methods

Data from the Parkland Hospital palliative care database, which tracked all consults for this period, were analyzed. Logistic regression was used to identify predictors of hospice use, and Cox proportional hazards modeling to examine survival.

Results

There were 5,083 palliative care consults over the study period. More patients were Black (41%) or White (31%), and younger than 65 years old (75%). Cancer patients or those who received palliative care services longer were more likely to receive hospice; those who had no form of health care assistance were less likely. There were no racial/ethnic differences in hospice use.

Conclusion

In this cohort, there were no racial/ethnic disparities in hospice use. Those who had no form of health care assistance were less likely to receive hospice.

Keywords: Palliative care, hospice, safety net, disparities

The safety net is a term used to describe hospitals or health care systems that provide care to the poor and underserved. It is estimated that every year, 10 million people receive care from public hospitals and health systems.1 These public hospitals often serve low-income patients with no or limited health insurance as well as many Medicaid beneficiaries and people who need special services. Safety-net hospitals often provide care to people of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, and some estimate that at least 65% of individuals receiving inpatient care in these hospitals were classified as Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, or other races.1 Given that those of low socioeconomic status (SES) have disproportionately higher cancer death rates than those with higher SES2 and often have other chronic or end-stage diseases, safety-net populations would be expected to have significant needs for palliative and end-of-life care.

Prior work suggests that Blacks and members of other underrepresented groups are less likely to utilize palliative care for pain and symptom management and hospice for care at the end of life than their White counterparts.3–11 Possible reasons for this disparity are many, including a lack of knowledge about these options for care on the part of patients and their families.12,13 Cultural and spiritual beliefs and an overall desire for more aggressive therapies at the end of life are additional possible reasons that racial/ethnic differences exist in the use of palliative and hospice care.13–16 Poverty in and of itself is a barrier to access to health care in general and end-of-life care specifically,17 and pharmacies in predominantly non-White neighborhoods in certain areas have been found not to stock sufficient medications to treat patients with severe pain adequately because of regulations with regard to disposal, illicit use and fraud, low demand, and fear of theft,18 further complicating an already complex health care dynamic.

An additional contributor to underuse of hospice care among the underserved may be upstream barriers or under-referral to a palliative care expert. We took advantage of a registry of consecutive patients seen over 11 years by our palliative care inpatient and outpatient service in a large, urban safety-net health system to pursue the following aims: 1) to describe the sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of patients cared for by our palliative care service; and 2) to examine differences in use of hospice and outcomes by race and ethnicity.

Methods

Study setting and patient population

We conducted a retrospective analysis using a registry of all consecutive patients seen by the Parkland Hospital and Health System (Parkland) palliative care service in the inpatient or outpatient setting from January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2010. Parkland is an integrated delivery system comprising a 900-bed teaching hospital, hospital-based outpatient clinics (including the palliative care clinic), and 11 community-based primary care centers. It is the sole safety-net provider for all of Dallas County, so it is responsible for all of the uninsured individuals in a large, diverse Southwestern metropolitan area. Eligible Dallas County residents receiving care at Parkland may qualify for charity health care assistance. This health care assistance plan, however, is not health insurance and does not cover hospice or home health services. The palliative care program at Parkland Hospital does not have specific outreach programs or advertisements that inform patients and families of the services they provide.

Data collection and measurements

The palliative care service database contains information on all patients seen during an inpatient consult or in the outpatient palliative care clinic including age, sex, race/ethnicity, primary diagnosis, insurance, date of initial palliative care evaluation, date of discharge from the palliative care service or clinic, date of death, location of death (if known), referral to hospice, and receipt of hospice services. The patients were followed in the outpatient palliative care clinic or throughout their inpatient hospital course if that was when the consult was obtained. Follow-up phone calls were made to each patient periodically to determine their current status (i.e., whether they were living or deceased). This study was approved by the hospital and University’s integrated institutional review board.

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to examine baseline characteristics of patients and processes and outcomes of care overall and stratified by race/ethnicity. The chi-square test was used for analysis of ordinal or dichotomous variables, and the ANOVA test used for continuous variables. We used logistic regression first to identify univariate associations between patient characteristics and referral to hospice. Patient and clinical characteristics associated with hospice referral in the unviariate analyses at the p<.20 level were entered into a stepwise multivariable logistic regression to identify independent predictors of hospice referral. We present unadjusted and adjusted odds of receiving hospice services after controlling for age, sex, primary diagnosis, insurance status, and the year of palliative care service. Adjusted differences in survival by race/ethnicity were examined using Cox proportional hazard regression, adjusting for baseline age, sex, primary diagnosis, insurance, the year of palliative care service, and hospice use (coded as a time-dependent variable). This final multivariate Cox model was based on the stepwise variable selection procedure as well as clinical consideration. We used SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC) and Stata 11.0 (College Station, TX) software and significance levels of p<.05 for all statistical comparisons.

Results

Patient characteristics

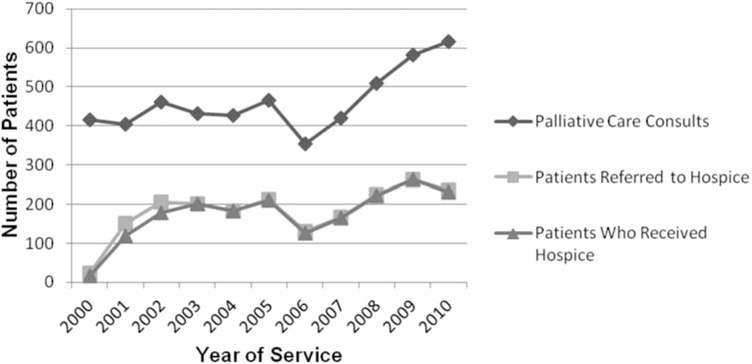

A total of 5,083 patients received palliative care consults or clinic visits during the study period. More than 4/10 (40.7%) were non-Hispanic Black, while 31.1% were non-Hispanic White, 24.1% were Hispanic, and 4.2% were Asian (see Table 1). Overall, 41% of Parkland patients are non-Hispanic Blacks, 32% Hispanics, 20% non-Hispanic Whites, and 7% other races/ethnicities. The mean patient age was 56.6 years and ranged from 18 to 101 years of age. The majority of patients (75.4%) were younger than 65 years of age, and more than half (53.7%) were male. The primary diagnosis was cancer for the vast majority of patients (83.5%). Among those with cancer, lung cancer (17.3%), breast cancer (9.3%), colon cancer (7.0%), hepatocellular cancer (6.4%), head and neck cancer (5.1%), and pancreatic cancer (4.2%) were the most common. Other primary diagnoses included liver cirrhosis (2.4%), end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (1.6%), and AIDS (1.5%). More than 40% of patients participated in the county charity health care assistance program, while 24.1% of patients received Medicare, 17.4% Medicaid, and 2.6% were privately insured. Eleven percent of patients had no form of health care coverage or assistance. Most patients died at home (34.9%) or during an inpatient hospitalization or emergency department visit (22.8%). Figure 1 illustrates the trends in palliative care consults, hospice referrals and hospice enrollment in patients seen over the 11-year study period.

Table 1.

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS OF PARKLAND PATIENTS RECEIVING PALLIATIVE CARE CONSULTS (2000–2010) (N = 5083)

| Characteristic | All Patients N = 5083a | Non-Hispanic White n = 1568 | Non-Hispanic Black n = 2063 | Hispanic n = 1219 | Asian n = 211 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 56.6 | 56.9 | 58.3 | 56.4 | 60.0 | < 0.001** |

| Female (%) | 46.3 | 43.2 | 46.7 | 49.4 | 47.9 | 0.01* |

| Insurance Type (%) | <0.001** | |||||

| County Programb | 44.8 | 47.2 | 31.7 | 62.0 | 54.5 | |

| Medicaid | 17.4 | 15.1 | 22.9 | 11.2 | 17.1 | |

| Medicare | 24.1 | 21.5 | 34.0 | 13.0 | 12.8 | |

| Private Insurance | 2.6 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 1.0 | |

| Uninsured | 11.1 | 13.1 | 8.1 | 12.8 | 14.7 | |

| Cause of Deathc(%) | < 0.001** | |||||

| Cancer | 83.8 | 82.1 | 86.6 | 81.0 | 86.7 | |

| Liver Cirrhosis | 2.4 | 2.9 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 1.9 | |

| AIDS | 1.4 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 0.0 | |

| ESRDd | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 1.0 | |

| CHFe | 1.3 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 0 | |

| Site of Death (%) | <0.001** | |||||

| Home | 34.9 | 36.6 | 32.6 | 35.4 | 39.3 | |

| Hospitalf | 22.8 | 21.7 | 23.8 | 22.8 | 21.3 | |

| Nursing Home | 4.5 | 5.0 | 6.1 | 1.3 | 2.8 | |

| Inpatient Hospice | 1.9 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 0.5 | |

| Other/Unknown | 35.9 | 34.2 | 35.5 | 38.8 | 36.0 | |

| Mean Duration of Palliative Care | ||||||

| Services, years | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.78 |

| Referred to Hospice (%) | 39.9 | 38.7 | 38.5 | 41.0 | 39.8 | 0.50 |

| Received Hospice (%) | 37.6 | 37.4 | 37.1 | 38.5 | 38.9 | 0.86 |

p-v alue≤.01

p-v alue≤.001

Missing race/ethnicity data on 22 patients

A charity health care assistance program for residents of Dallas County

Only the 5 leading causes of death are listed

End Stage Renal Disease

Congestive Heart Failure

Hospital includes ED, inpatient ward, and ICU

Figure 1.

Trends in End-of-Life Care Services per year of Palliative Care Service, 2000–2010

Comparison of patients by race/ethnicity

The same baseline characteristics as noted above were examined with stratification by race/ethnicity (see Table 1). Hispanic and non-Hispanic White patients died at slightly younger ages than non-Hispanic Black and Asian patients (p<.001). Hispanic patients more often had ESRD and cirrhosis than members of other racial/ethnic groups, and non-Hispanic Black and Asian patients more commonly had cancer of some type as a primary diagnosis (p<.001). Blacks more often had Medicare (34.0%) or Medicaid (22.9%), while Hispanics, non-Hispanic Whites, and Asians participated in the county charity assistance program in greater percentages than their respective counterparts. There were no statistically significant differences in hospice referral or duration of palliative care services. The median time to death after palliative consult in days, by race was as follows: 50 days for White patients, 55 days for Black patients, 65 days for Hispanic patients, and 57 days for Asian patients.

Predictors of hospice use and survival by race

In univariate analysis, patients with cancer as a primary diagnosis (OR: 2.08, 95% CI: 1.75 to 2.47) were more likely to go on to receive hospice care. Those who were on palliative care in later years of development of the palliative care service were less likely to get hospice (0.94, 0.93 to 0.96). Patients who did not have insurance were less likely to receive hospice (OR: 0.62, 0.51 to 0.76), while there was no statistically significant difference in hospice enrollment among patients who received county health care (OR: 1.08, 0.96 to 1.22) (see Table 2). There was also no statistically significant difference in hospice utilization by race/ethnicity. Some of these findings held true on multivariable logistic regression analysis. After adjustment for age, race/ethnicity, gender, insurance status, primary diagnosis, and the year palliative care was initiated, palliative care patients with cancer as a primary diagnosis (AOR: 2.15, 95% CI 1.80 to 2.56) were more likely to receive hospice services. Again, those who were uninsured (AOR 0.63, 0.51 to 0.78) were less likely to receive hospice. There were no statistically significant differences in hospice use by race/ethnicity on the adjusted analysis (see Table 2). On adjusted analysis, however, those who received services in later years of development of the palliative care service were more likely to go to hospice (1.09, 1.07 to 1.11). A Cox proportional hazard model with adjustment for age, gender, insurance status, cancer diagnosis, year of the palliative care service, and hospice status, revealed a difference in survival based on race/ethnicity among Hispanic patients, but not for Asian and African American patients when compared with White patients. The adjusted hazard ratio (AHR) by race/ethnicity is as follows: Hispanic AHR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.81 to 0.96; African American AHR: 1.04, 95% CI: 0.97 to 1.13; and Asian AHR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.77 to 1.08. (See Table 3.)

Table 2.

USE OF HOSPICE. SIMPLE AND MULTIVARIABLE LOGISTIC REGRESSION ANALYSIS

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.99 (0.86–1.13) | 0.95 (0.82–1.09) |

| Hispanic | 1.05 (0.90–1.22) | 1.06 (0.91–1.25) |

| Asian | 1.07 (0.79–1.43) | 1.01 (0.75–1.37) |

| Insurance Status | ||

| Insured | Ref | Ref |

| No Insurance | 0.62 (0.51–0.76) | 0.63 (0.51–0.78) |

| County Charity Program | 1.08 (0.96–1.22) | 1.00 (0.88–1.14) |

| Cancer Diagnosis | 2.08 (1.75–2.47) | 2.15 (1.80–2.56) |

| Year of Palliative Care Service | 0.94 (0.93–0.96) | 1.09 (1.07–1.11) |

Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, gender, insurance status, primary diagnosis, and the year of palliative care service

OR = Odds Ratio

CI = Confidence Interval

AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio

Table 3.

ADJUSTED COX PROPORTIONAL HAZARDS MODEL OF SURVIVAL

| Predictor | Adjusted Hazard Ratioa | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | — |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.04 | 0.97–1.13 |

| Hispanic | 0.88 | 0.81–0.96 |

| Asian | 0.91 | 0.77–1.08 |

| Age | 1.01 | 1.00–1.01 |

| Gender (female) | 1.15 | 1.08–1.23 |

| Insurance Status | ||

| No Insurance | 1.40 | 1.26–1.57 |

| County Charity Program | 1.21 | 1.12–1.29 |

| Cancer Diagnosis | 1.02 | 0.93–1.11 |

| Year of Palliative Care Service | 0.97 | 0.96–0.98 |

| Received Hospice | 25.37 | 19.66–32.74 |

Adjusted for age, gender, insurance status, primary diagnosis, year of palliative care service, and receipt of hospice

CI = Confidence Interval

Discussion

Racial/ethnic disparities in end-of-life care have been identified throughout the literature, and African Americans, Hispanics/Latinos, and members of other underrepresented groups have been shown to use hospice less often than their White counterparts. In our study of palliative care patients, however, there were no statistically significant differences in hospice use by race or ethnicity on univariate or multivariable analysis. Patients in this study received palliative care and the interdisciplinary care that palliative medicine provides. This exposure to palliative care physicians, nurses, social workers, and chaplains throughout the course of illness may assist patients and their families in making the often difficult transition to hospice care.

Our study of patients who received palliative care consultation in a safety-net hospital system revealed some interesting findings. For instance, we found that people of low socioeconomic status and members of underrepresented minority groups use palliative care and often receive hospice services at the end of life in our public hospital. We found that despite literature that suggests that there are racial/ethnic disparities in hospice utilization, there were no statistically significant racial/ethnic differences in hospice use in this patient population. We also found that on adjusted analysis, patients who were on the palliative care service in later years of development of the service were more likely to get hospice. This may be a result of practitioners gaining experience and exposure to hospice organizations over time that has resulted in greater successes in this regard. People who had no form of health care insurance or assistance were less likely to receive hospice, which confirms that despite our best efforts, providing end-of-life care to the uninsured continues to be a challenge among hospice and palliative medicine providers working within safety-net hospital systems. Our findings show that a significant percentage of palliative care patients in this study had cancer, and that having a cancer diagnosis was associated with hospice utilization. These findings suggest that opportunities to extend the scope of palliative care services to people with other life-limiting illnesses are present and should be explored.

This study has helped to identify opportunities for continued development of our palliative care program. For instance, cancer diagnosis was associated with hospice use in this study. When hospice care in the United States was established, cancer patients made up the largest percentage of hospice admissions. Cancer patients now make up 40.1% of hospice admissions nationally,19 and in our study 84% of palliative care patients had cancer of some type. Though people with cancer certainly benefit from palliation of their symptoms and hospice care at the end of life, strides can be made to extend services to people with other life-limiting illnesses. Furthermore, recent research has shown that palliative care intervention early in the disease trajectory may certainly be beneficial,20,21 and interventions utilizing electronic health records to prompt physicians to begin having discussions with advanced lung cancer patients about their end-of-life care preferences have also been successful.22 Additional interventions should be designed to increase patients’ awareness of palliative care early in the disease trajectory—particularly among those who historically underutilize these services.

In this study, those who had no form of health insurance or assistance were less likely than the insured to receive hospice services, though these findings did not hold true for patients who received charity assistance when compared with people with some form of health insurance. Having charity assistance does allow patients access to health care that they would not otherwise have, and though this assistance does not cover hospice services, it allows for health care resources that would not otherwise be available. People with county assistance may be more willing to seek care than those who have no coverage, increasing their eligibility for donated or charity hospice services. It may keep them in the care continuum, such that hospice services are a possibility if and when they are available. Furthermore, previous research suggests that enrollment of patients in a comprehensive public assistance program may result in hospice enrollment comparable to previously reported hospice use by insured individuals and uniformly lower use of hospital resources, including emergency room visits, inpatient admissions, and intensive care unit stays.23,24 Comprehensive palliative care programs have been developed to provide care to populations served by safety-net public health systems and have been successful;25 however, providing palliative care and end-of-life care to the underrepresented and underserved continues to be a challenge, and continued efforts should be made to provide them with this much-needed care. Our survival model revealed that Hispanic patients lived longer than patients of other racial/ethnic backgrounds. While this result was statistically significant, the median survival was similar across racial/ethnic groups, and therefore we do not feel that this is a clinically significant finding.

Certain limitations should be taken into account in this study. It was performed at a single site, which may limit the external validity of the results to other care settings and people of differing socioeconomic status. Furthermore, the literature has shown that regional variation and hospital, nursing home or health care system practice patterns may play a role in racial differences in care.26–28 These effects may explain the results of our analysis; consequently, the role of these effects on end-of-life care treatment on our population compared with other hospital systems is something that should be explored. Additionally, some patients were lost to follow-up, making it difficult to determine the locus of their terminal care. In the future, studies that examine the palliative and end-of-life care of patients at multiple safety-net hospitals should be conducted to determine if our findings can be generalized or are unique to our patient population.

Despite these limitations, certain important findings should be taken into account. Our palliative care database explores palliative and end-of-life care among a relatively young and racially/ethnically diverse population that would be difficult to capture in a claims-based analysis.29 In this population with limited resources, more than one-third of patients who received palliative care went on to receive hospice services. Additionally, there were no differences in hospice utilization or survival by race, though socioeconomic status (as defined by possession of health coverage, in this instance) may certainly play a role. Future research should examine the correlation between socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and preferences for end-of-life care. Additionally, interventions should be designed to introduce palliative care earlier in the disease trajectory in an effort to reduce disparities in end-of-life care, be they based on socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, or cultural beliefs.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted with support from UT-STAR, NIH/NCATS Grant Number KL2TR000453. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of UT-STAR, UT Southwestern Medical Center and its affiliated academic and health care centers, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Ramona L. Rhodes, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Division of General Internal Medicine, in Dallas; Department of Clinical Sciences, in Dallas.

Lei Xuan, Department of Clinical Sciences, in Dallas.

M. Elizabeth Paulk, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Division of General Internal Medicine, in Dallas.

Heather Stieglitz, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Division of General Internal Medicine, in Dallas.

Ethan A. Halm, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Division of General Internal Medicine, in Dallas; Department of Clinical Sciences, in Dallas.

Notes

- 1.Regenstein M, Huang J. Stresses to the Safety Net: The Public Hospital Perspective. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Facts and Figures 2012. The American Cancer Society; Available at: http://www.cancer.org/acs [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen LL. Racial/ethnic disparities in hospice care: a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2008. June;11(5):763–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lepore MJ, Miller SC, Gozalo P Hospice use among urban Black and White U.S. nursing home decedents in 2006. Gerontologist. 2011. April;51(2):251–60. Epub 2010 Nov 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connor SR, Elwert F, Spence C, Christakis NA. Racial disparity in hospice use in the United States in 2002. Palliat Med. 2008. April;22(3):205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwak J, Haley WE, Chiriboga DA. Racial differences in hospice use and in-hopsital death among Medicare and Medicaid dual-eligible nursing home residents. Gerontologist. 2008. February;48(1):32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greiner KA, Perera S, Ahluwalia JS. Hospice usage by minorities in the last year of life: results from the National Mortality Followback Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003. July;51(7):970–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardy D, Chan W, Liu CC, Cormier JN, Xia R, Bruera E, Du XL. Racial disparities in length of stay in hospice care by tumor stage in a large elderly cohort with non-small lung cancer. Palliat Med. 2012. January;26(1):61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardy D, Chan W, Liu CC, Cormier JN, Xia R, Burera E, Du XL. Racial disparities in the use of hospice services according to geographic residence and socioeconomic status in an elderly cohort with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2011. April 1;117(7):1506–15. Epub 2010 Nov 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ludke RL, Smucker DR. Racial differences in the willingness to use hospice services. J Palliat Med. 2007. December;10(6):1329–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tanis D, Tulsky JA. Racial differences in hospice revocation to pursue aggressive care. Arch Intern Med. 2008. January 28;168(2):218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhodes RL, Teno JM, Welch LC. Access to Hospice for African Americans: Are They Informed about the Option of Hospice? J Palliat Med. 2006. April;9(2):268–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Born W, Greiner KA, Sylvia E. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about end-of-life care among inncer-city African Americans and Latinos. J Palliat Med 2004. April;7(2):247–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, tulsky JA. What explains racial differences in the use of advance directives and attitudes toward hospice care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008. October;56(10):1953–8. Epub 2008 Sep 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson KS, Elbert-Avial KI, Tulsky JA. The influence of spiritual beliefs and practices on the treatment preferences of African Americans: a review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005. April;53(12):711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith AK, McCarthy EP, Paulk E, et al. (2008). Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning among patients with cancer: impact of terminal illness acknowledgment, religiousness, and treatment preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2008 September;26(25): 4131–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyckholm LJ, Coyne PJ, Kreutzer KO, et al. Barriers to effective palliative care for low-income patients in late stages of cancer: Report of a study and strategies for defining and conquering barriers. Nurs Clin North Am. 2010. September;45(3):399–409. Epub 2010 May 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison RS, Wallenstein S, Natale SK, Snezel RS, Huang L. “We Don’t Carry That”— Failure of pharmacies in predominantly nonWhite neighborhoods to stock opioid analgesics. N Engl J Med. 2000. April 6;342(14):1023–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America, 2011 Edition. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010. August 19;363(8):733–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, Muzikansky A, et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013. February 1;30(4):394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Temel JS, Greer JA, Gallagher ER, Jackson VA, et al. Electronic prompt to improve outpatient code status documentation for patients with advanced lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013. February 20;31(6):710–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergman J, Chi AC, Litwin MS. Quality of end-of-life care in low-income, uninsured men dying of prostate cancer. Cancer. 2010. May 1;116(9):2126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergman J, Kwan L, Fink A, et al. Hospice and emergency room use by disadvantaged men dying of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2009. May;181(5):2084–9. Epub 2009 Mar 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kvale EA, Williams BR, Bolden JL, Padgett CG, Bailey FA. The Balm of Gilead Project: a demonstration project on end-of-life care for safety-net populations. J Palliat Med. 2004. June;7(3):486–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng NT, Mukamel DB, Caprio T, Shubing C, Temekin-Greener H. Racial disparities in in-hospital death and hospice use among nursing home residents at the end of life. Med Care. 2011. November;49(11):992–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper A, Rivara FP, Wang J, MacKenzie EJ, Jurkovich GJ. Racial disparities in intensity of care at the end-of-life: Are trauma patients the same as the rest? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012. May;23(2):857–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rathore SS, Masoudi FA, Havranek EP, Krumholz HM. Regional variation in racial differences in the treatment of elderly patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2004. December;117(11):811–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan RO, Wei II, Virnig BA. Improving identification of Hispanic males in Medicare: use of surname matching. Med Care. 2004. August;42(8):810–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]