Abstract

Background

England’s Time to Change programme to reduce mental health-related stigma and discrimination included a social marketing campaign using traditional and social media, and targeted middle-income groups aged 25–45 between 2009 and 2016. From 2017, the same age group on low to middle incomes were targeted, and the content focused on men’s mental health, by changing the advertising and adapting the ‘key messages’. This study investigates changes in stigma-related public knowledge, attitudes and desire for social distance in England since Time to Change began in 2008–19 and for 2017–19.

Methods

Using data from a face-to-face survey of a nationally representative quota sample of adults for England, we evaluated longitudinal trends in outcomes with regression analyses and made assumptions based on a simple random sample. The pre-existing survey used a measure of attitudes; measures of knowledge and desire for social distance were added in 2009.

Results

Reported in standard deviation units (95% CI), the improvement for knowledge for 2009–19 was 0.25 (0.19, 0.32); for attitudes, 2008–19, 0.32 (0.26, 0.39) and for desire for social distance, 2009–19 0.29 (0.23, 0.36). Significant interactions between year and both region and age suggest greater improvements in London, where stigma is higher, and narrowing of age differences. There were significant improvements between 2017 and 2019 in knowledge [0.09 (0.02, 0.16)] and attitudes [0.08 (0.02, 0.14)] but not social distance.

Conclusion

The positive changes support the effectiveness of Time to Change but cannot be definitively attributed to it. Inequalities in stigma by demographic characteristics present targets for research and intervention.

Introduction

Stigma and discrimination against people with mental illness have substantial public health impact, contributing to inequalities1 including: poor access to mental and physical healthcare;2 reduced life expectancy;3 exclusion from higher education and employment;4 increased risk of contact with criminal justice systems; victimization;5 poverty and homelessness. There is growing investment in and evidence for the effectiveness of anti-stigma interventions, including programmes targeted at the general population and/or specific groups.6

In England, the current national programme against stigma and discrimination is Time to Change,7 delivered by the charities Mind and Rethink Mental Illness. Its first phase ran from 2007 to 2011, including a social marketing campaign launched in January 2009 aimed at adults aged 25–44 in middle-income groups, and work with target groups. To evaluate Time to Change’s effect on public stigma, in 2009 measures of stigma-related knowledge and desire for social distance were added to the pre-existing national Attitudes to Mental Illness survey.8 This survey was first commissioned by the Department (Ministry) of Health in 1994. While it could be argued that stigma-related knowledge, attitudes and desire for social distance among the general public are less important than the experience of stigma (comprising both awareness of public stigma and direct experiences of discrimination), research suggests an association between these two aspects of stigma.9

Time to Change phase 2 was funded for 2011–15, with an extension to 2016, and included social marketing aimed at the same target group of adults.10 Between 2009 and 2015, there were significant improvements in stigma-related knowledge, attitudes and desire for social distance.11 A survey of mental health service users from 2008 to 2014 showed evidence for a reduction in direct experiences of discrimination across a number of areas of life, particularly in informal relationships.12

Time to Change phase 3 runs 2016–21. The social marketing campaign from 2017 is aimed again at those aged 25–44, in an income group overlapping but lower than previous phases, and focuses on men’s mental health. The previous key messages to encourage supportive contact were reworked for this target group. The campaign encouraged people to ‘be in their mate’s corner’ to harness the power of friendship, and also used humour. The campaign then developed this idea further, encouraging people to ‘ask twice’ if they feel like someone they know is acting differently. Hence, the campaign promotes empathy as a key mediator of the effect of contact on prejudice13 while encouraging people to maintain contact14 (as opposed to social distancing). In the process, the campaign delivers parasocial (virtual) contact14 and promotes imagined contact.15 For parents, a tailored section was included in the Time To Change website; and short films were used in public relations and social media.

This change in the target group is in part due to persisting differences found previously showing less positive outcomes in men and lower socio-economic groups.16 As stigma is a cause of health inequalities, it is important that anti-stigma programmes do not result in widening of stigma among demographic groups. Indeed, we previously identified narrowing of pre-existing age and regional differences but none by sex, ethnicity or socio-economic group.16

Aims of the study

This study examines longitudinal trends in: mental health-related knowledge, attitudes to mental illness and desire for social distance from people with mental illness among the general public in England over the course of the whole of Time to Change’s social marketing campaign (launched in 2009) and since the change in target group (2017–19). We investigate whether these trends vary by demographic groups (age, sex, ethnicity or socio-economic group) and region of England.

Methods

Data source

The Attitudes to Mental Illness survey has been carried out in England every year from 2008 to 2017 and every 2 years since 2017, by the agency Kantar TNS.11,16,17 It was previously carried out every few years from 1994.8 There are approximately 1700 respondents for each survey year. Respondents are not resampled in later surveys. A quota sampling frame is used to ensure the survey sample is nationally representative of adult residents in England aged 16 and over: census small area statistics and the Postcode Address File define sample points that are randomly selected and stratified by Government Office Region (GOR) and social status. Sampling errors were calculated on an assumption of a simple random sampling method. Information on the survey methods can be found at: https://www.time-to-change.org.uk/sites/default/files/Attitudes_to_mental_illness_2014_report_final_0.pdf. All interviews were carried out face-to-face in respondents’ homes by trained personnel. The measures of knowledge and desire for social distance were added in 2009, just before the social marketing campaign was launched; therefore, the baseline for public attitudes is 2008 and for the other outcomes is 2009.

Measures

Mental health-related knowledge

Stigma-related knowledge was measured by the Mental Health Knowledge Schedule (MAKS),18 which comprises six items covering stigma-related mental health knowledge areas: help seeking, recognition, support, employment, treatment and recovery; and six about classification of various conditions as mental illnesses. The standardized total score of the first six items was used; where a higher standardized MAKS score indicates greater knowledge. Previous work showed the overall test–retest reliability of the MAKS is 0.71 (Lin’s concordance statistic). Item retest reliability, using a weighted kappa, ranged from 0.57 to 0.87, indicating moderate to substantial agreement between time points. The overall internal consistency among items is 0.68 (Cronbach’s alpha). This relatively low internal consistency reflects the different domains of knowledge covered by the items; the MAKS was not designed as a scale and instead can be used to track knowledge in specific areas using individual items.18

Mental health-related attitudes

Public attitudes towards mental health were measured using 26 of the 40 items from the Community Attitudes towards the Mentally Ill scale (CAMI),19 plus one added item on employment-related attitudes. This revision to the original CAMI was made by another researcher when the UK Department of Health first commissioned the Attitudes to Mental Illness Survey.8 Items referring to views about possible deinstitutionalization were removed, as they were anachronistic; deinstitutionalization had already occurred. The remaining items cover attitudes about social exclusion, benevolence, tolerance and support for community mental health care and were rated from 1 (strong disagreement) to 5 (strong agreement). The standardized total score of the CAMI was used and a higher score indicates less stigmatizing attitudes. The overall internal consistency of the CAMI in this dataset is 0.87 (Cronbach’s alpha).

Desire for social distance

This is measured using the Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale (RIBS),20 derived from the Star Social Distance Scale.21 For the desire for social distance outcome, i.e. the Intended Behaviour subscale, four items assess the level of desired future contact with people with mental health problems, in terms of: living with, working with, living nearby and continuing a relationship with someone. A higher score indicates less desire for social distance. The total RIBS intended behaviour score was standardized. The overall test–retest reliability of total RIBS score has been shown to be 0.75 (Lin’s concordance statistic). Item retest reliability, using a weighted kappa, ranged from 0.62 to 1.0, indicating moderate to substantial agreement between time points. The overall internal consistency, based on Cronbach’s alpha among the subscale items, was 0.85.20

Socio-economic status

Socio-economic status was categorized using the Market Research Society’s classification system into four groups (A plus B combined, C1, C2 and D plus E combined). This was based on the occupation of the household’s chief income earner: A plus B represents professional/managerial occupations, C1 represents other non-manual occupations, C2 represents skilled manual occupations and D plus E represents semi-/unskilled manual occupations or people dependent on state benefits.

Familiarity with someone with a mental health problem

Knowing someone with a mental health problem or familiarity with mental illness is associated with mental health-related knowledge, attitudes and desire for social distance.17 Familiarity was measured using the question: Who is the person closest to you who has or has had some kind of mental illness? The responses included: immediate family, partner, other family, friend, acquaintance, work colleague, self, other or no-one known. These were categorized into three groups (self, other and none).

Government office region

The lowest level information on participants’ location is the GOR categories as described by the UK Government’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) (ons.gov.uk) (see table 1).

Table 1.

Participant demographics by survey year, un-weighted frequency and weighted per cent

| 2008 (n = 1703) | 2009 (n = 1751) | 2010 (n = 1745) | 2011 (n = 1741) | 2012 (n = 1717) | 2013 (n = 1727) | 2014 (n = 1714) | 2015 (n = 1736) | 2016 (n = 1765) | 2017 (n = 1720) | 2019 (n = 1785) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Female | 925 (51.7) | 939 (51.5) | 939 (51.7) | 912 (51.5) | 924 (51.3) | 926 (51.0) | 893 (50.9) | 919 (51.6) | 918 (51.4) | 938 (50.8) | 933 (51.1) |

| Male | 778 (48.3) | 812 (48.5) | 806 (48.3) | 829 (48.5) | 793 (48.7) | 801 (49.0) | 821 (49.1) | 817 (48.4) | 847 (48.6) | 782 (49.2) | 852 (48.9) |

| Age mean (SD) | 46.7 (18.9) | 46.0 (18.8) | 46.5 (18.4) | 46.4 (19.2) | 46.4 (19.1) | 45.9 (18.3) | 46.0 (18.8) | 46.4 (19.2) | 46.3 (19.7) | 43.7 (20.0) | 46.0 (20.4) |

| Age group, n (%) | |||||||||||

| 16–24 | 188 (13.2) | 247 (14.3) | 240 (14.6) | 235 (14.4) | 258 (14.6) | 289 (14.6) | 221 (14.4) | 242 (14.1) | 211 (13.6) | 220 (17.8) | 275 (14.5) |

| 25–44 | 562 (36.0) | 633 (35.9) | 540 (35.1) | 545 (35.4) | 580 (34.8) | 568 (36.1) | 514 (36.2) | 528 (35.3) | 597 (35.5) | 491 (37.4) | 521 (36.2) |

| 45–64 | 525 (32.1) | 512 (31.3) | 549 (31.5) | 499 (30.6) | 506 (31.3) | 486 (31.1) | 506 (30.6) | 488 (31.5) | 488 (31.7) | 507 (27.7) | 484 (30.9) |

| 65+ | 428 (18.7) | 359 (18.5) | 416 (19.4) | 462 (19.5) | 373 (19.3) | 384 (18.3) | 473 (18.7) | 478 (19.0) | 469 (19.3) | 502 (17.1) | 505 (18.5) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Asian | 90 (5.5) | 112 (6.2) | 136 (8.5) | 134 (8.1) | 160 (9.7) | 127 (7.9) | 105 (6.6) | 120 (6.7) | 121 (7.0) | 76 (5.5) | 97 (6.5) |

| Black | 73 (4.4) | 63 (3.4) | 88 (4.9) | 64 (3.8) | 67 (3.8) | 66 (3.7) | 69 (4.0) | 99 (5.3) | 83 (4.7) | 61 (4.5) | 82 (4.7) |

| Other | 28 (1.9) | 26 (1.4) | 18 (1.1) | 20 (1.1) | 31 (1.8) | 44 (2.6) | 26 (1.6) | 39 (2.3) | 42 (2.6) | 41 (3.1) | 57 (3.7) |

| White | 1503 (88.1) | 1542 (89.0) | 1496 (85.5) | 1504 (87.0) | 1449 (84.7) | 1474 (85.9) | 1507 (87.8) | 1472 (85.7) | 1507 (85.7) | 1529 (87.0) | 1535 (85.1) |

| Socio-economic Status, n (%) | |||||||||||

| AB | 315 (21.0) | 279 (19.4) | 300 (20.2) | 322 (20.5) | 292 (19.3) | 302 (20.5) | 353 (21.4) | 335 (22.2) | 271 (18.9) | 350 (22.4) | 291 (20.5) |

| C1 | 433 (29.6) | 454 (32.2) | 464 (31.7) | 450 (29.8) | 456 (31.0) | 445 (30.4) | 457 (29.2) | 432 (28.4) | 430 (30.6) | 501 (35.3) | 443 (30.4) |

| C2 | 363 (21.1) | 389 (20.8) | 342 (19.2) | 340 (21.1) | 368 (21.6) | 362 (20.8) | 333 (20.5) | 354 (20.4) | 371 (20.7) | 296 (15.4) | 383 (20.9) |

| DE | 592 (28.2) | 629 (27.6) | 639 (28.8) | 629 (28.6) | 601 (28.1) | 618 (29.1) | 571 (29.0) | 615 (29.1) | 693 (29.8) | 573 (26.9) | 668 (28.3) |

| Familiarity with mental health n (%) | |||||||||||

| Self | 102 (6.0) | 92 (5.0) | 75 (4.2) | 90 (5.6) | 111 (6.4) | 120 (6.6) | 126 (7.4) | 124 (6.9) | 124 (7.4) | 143 (9.2) | 152 (8.9) |

| Other | 665 (42.5) | 902 (54.0) | 892 (53.0) | 896 (53.5) | 926 (55.9) | 963 (57.9) | 953 (57.5) | 963 (58.1) | 1013 (61.1) | 980 (58.8) | 929 (55.0) |

| None | 846 (51.5) | 718 (41.0) | 738 (42.8) | 706 (41.0) | 645 (37.7) | 610 (35.5) | 606 (35.1) | 632 (35.0) | 586 (31.5) | 566 (32.0) | 659 (36.1) |

| Region n (%) | |||||||||||

| North East | 86 (5.3) | 86 (5.0) | 88 (4.8) | 83 (4.8) | 95 (5.5) | 82 (4.9) | 76 (4.4) | 76 (5.5) | 98 (5.3) | 73 (4.6) | 86 (4.7) |

| North West | 218 (12.9) | 245 (14.2) | 244 (13.6) | 233 (13.6) | 235 (12.8) | 233 (13.6) | 240 (13.8) | 280 (20.5) | 242 (13.8) | 238 (13.6) | 250 (13.2) |

| York and Hum | 172 (9.8) | 174 (9.6) | 178 (9.9) | 176 (10.5) | 185 (10.3) | 174 (9.9) | 169 (10.6) | 131 (9.6) | 186 (10.3) | 142 (7.9) | 188 (10.7) |

| East Midlands | 157 (9.1) | 151 (8.7) | 147 (8.6) | 159 (8.5) | 129 (8.2) | 152 (8.6) | 140 (8.0) | 139 (7.2) | 143 (8.1) | 152 (7.8) | 154 (9.0) |

| West Midlands | 173 (9.7) | 192 (10.9) | 190 (10.5) | 195 (10.4) | 186 (10.9) | 188 (10.8) | 189 (10.6) | 167 (8.6) | 189 (10.6) | 188 (11.0) | 173 (9.7) |

| East | 186 (11.3) | 187 (10.4) | 193 (11.3) | 192 (10.6) | 178 (10.3) | 188 (11.0) | 202 (11.3) | 202 (10.5) | 191 (11.3) | 199 (10.8) | 196 (11.7) |

| South East | 287 (16.9) | 278 (16.7) | 282 (17.0) | 285 (16.9) | 291 (17.6) | 285 (16.0) | 287 (17.1) | 305 (16.0) | 290 (16.9) | 295 (17.1) | 283 (15.6) |

| South West | 161 (9.1) | 176 (10.1) | 173 (9.6) | 176 (10.5) | 170 (10.1) | 179 (10.4) | 164 (9.8) | 146 (7.3) | 176 (10.0) | 181 (10.5) | 171 (9.0) |

| London | 263 (16.0) | 262 (14.5) | 250 (14.8) | 242 (14.3) | 248 (14.4) | 246 (14.9) | 247 (14.6) | 290 (14.7) | 250 (13.8) | 252 (16.8) | 284 (16.4) |

Awareness of Time to Change

From 2012, awareness of Time to Change was assessed using recent campaign materials at the end of the survey.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics for participant demographics and crude outcome scores were calculated and reported by survey year and region. All analyses were weighted by gender, age and ethnicity to reflect population characteristics in England. Survey weights were taken from the UK Government’s ONS. To create analysis models, the quota sample was treated as a probability sample. Three initial multiple linear regression models were used to evaluate patterns of change in: (i) public knowledge (MAKS); (ii) public attitudes (CAMI) and (iii) public desire for social distance (RIBS Intended Behaviour) of mental health problems. All the models used the standardized scores of the measures as the dependent variables; therefore, the outputs were interpreted in standard deviation units.

To evaluate changes over time, all the models included a fixed effect for year using a categorical dummy variable. To obtain estimates for the proportion of the population whose outcomes changed between two comparative years (2019 and baseline; or 2019 and 2017), the distributional approach was used, which uses the parameters of the normal distribution.22 This method converts results from linear regression models into corresponding proportions, using the area under the standard normal curve. Other covariates were included to control for differences in participant demographics: gender (female vs. male), age category (16–24, 25–44, 45–64 and 65+), ethnicity (Asian, Black, other and White), socio-economic status (A plus B, C1, C2 and D plus E), familiarity with someone with a mental health problem (self, other and none) and region. The analysis is the same as for earlier evaluations of Time to Change data using this data source,11,16,17 with the exception that the variable for region of England was not included in the analysis for the evaluation of Time to Change phase 1 using this survey.17 Interactions were tested between survey year and demographic subgroups to see whether patterns of change in the outcomes differed by groups. The interaction terms were added separately to the initial models and evaluated for statistical significance using a Wald test. All analyses were carried out using Stata version 15.1.23

Ethics

The King’s College London Psychiatry, Nursing and Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittee exempted this study as secondary analysis of anonymized data.

Results

Survey sample characteristics

The demographics of participants are reported by survey year in table 1. From 2012 to 2019, awareness of Time to Change among the total sample was 27.2% overall (ranging from 21.6% in 2014 to 44.4% in 2013), with differences by ethnicity (White 28.1%, Black 25.1% and Asian 18.9%). In the target group of people in socio-economic groups C1, C2 and D, it was 19.2%.

Changes in mental health-related public knowledge

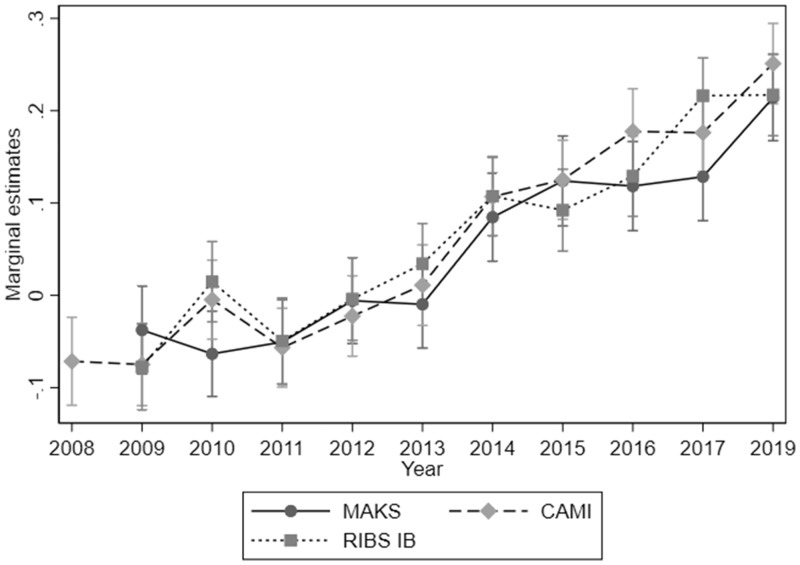

Participants in 2019 scored 0.25 (0.19, 0.32) SD units higher on the MAKS scale compared with those sampled and taking part in 2009 (see table 2). Using the distributional approach,22 this corresponds to an increase in mental health knowledge in 9.9% of people from 2009 to 2019. Figure 1 illustrates the change over time by plotting the marginal estimates of the standardized MAKS score by year. There were no significant interactions found. This means the improvement in stigma-related knowledge over time has not differed between subgroups of the population (age, sex, ethnicity or socio-economic status) or by region. There was a significant improvement between 2017 and 2019 in MAKS score, with a standard deviation unit change of 0.09 (0.02, 0.16). This is equivalent to an increase in mental health knowledge in 3.6% of people.

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression analyses of predictors of mental health-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviour among the general public

| Predictors | Knowledge: standardized Mental Health Knowledge Schedule (MAKS) score (n = 16 943) | Attitudes: standardized Community Attitudes to the Mental Ill (CAMI) score (n = 18 551) | Intended behaviour (IB): standardized Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale (RIBS) IB subscale score (n = 16 943) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized effect size (95% CI) | P-value | Standardized effect size (95% CI) | P-value | Standardized effect size (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Year | ||||||

| 2019 | 0.25 (0.19, 0.32)* | <0.001 | 0.32 (0.26, 0.39)* | <0.001 | 0.29 (0.23, 0.36)* | <0.001 |

| 2017 | 0.17 (0.10, 0.23)* | <0.001 | 0.25 (0.18, 0.31)* | <0.001 | 0.29 (0.23, 0.36)* | <0.001 |

| 2016 | 0.16 (0.09, 0.22)* | <0.001 | 0.25 (0.18, 0.32)* | <0.001 | 0.21 (0.14, 0.27)* | <0.001 |

| 2015 | 0.16 (0.09, 0.23)* | <0.001 | 0.20 (0.13, 0.26)* | <0.001 | 0.17 (0.11, 0.23)* | <0.001 |

| 2014 | 0.12 (0.05, 0.19)* | <0.001 | 0.18 (0.11, 0.24)* | <0.001 | 0.19 (0.12, 0.25)* | <0.001 |

| 2013 | 0.03 (−0.04, 0.09) | 0.415 | 0.08 (0.02, 0.15)* | 0.013 | 0.11 (0.05, 0.18)* | 0.001 |

| 2012 | 0.03 (−0.03, 0.10) | 0.348 | 0.05 (−0.02, 0.11) | 0.137 | 0.07 (0.01, 0.14)* | 0.026 |

| 2011 | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.05) | 0.700 | 0.01 (−0.05, 0.08) | 0.651 | 0.03 (−0.04, 0.09) | 0.399 |

| 2010 | −0.03 (−0.09, 0.04) | 0.445 | 0.07 (0.002, 0.13)* | 0.041 | 0.09 (0.03, 0.16)* | 0.004 |

| 2009 (ref) | – | – | −0.003 (−0.07, 0.06) | 0.917 | – | – |

| 2008 (CAMI ref) | – | – | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 0.15 (0.12, 0.18)* | <0.001 | 0.16 (0.13, 0.19)* | <0.001 | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.01) | 0.296 |

| Male (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Age | ||||||

| 16–24 | 0.06 (0.01, 0.11)* | 0.026 | 0.02 (−0.02, 0.07) | 0.323 | 0.52 (0.47, 0.57)* | <0.001 |

| 25–44 | 0.17 (0.13, 0.21)* | <0.001 | 0.13 (0.09, 0.16)* | <0.001 | 0.45 (0.41, 0.49)* | <0.001 |

| 45–64 | 0.25 (0.21, 0.29)* | <0.001 | 0.22 (0.19, 0.26)* | <0.001 | 0.40 (0.36, 0.44)* | <0.001 |

| 65+ (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Asian | −0.06 (−0.12, 0.002) | 0.062 | −0.44 (−0.49, −0.39)* | <0.001 | −0.37 (−0.44, −0.31)* | <0.001 |

| Black | −0.02 (−0.09, 0.06) | 0.676 | −0.36 (−0.42, −0.29)* | <0.001 | −0.25 (−0.33, −0.16)* | <0.001 |

| Other | −0.03 (−0.14, 0.08) | 0.598 | −0.24 (−0.34, −0.14)* | <0.001 | −0.20 (−0.31, −0.10)* | <0.001 |

| White (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Socio-economic status | 0.35 (0.30, 0.39)* | <0.001 | 0.40 (0.36, 0.44)* | <0.001 | 0.31 (0.27, 0.35)* | <0.001 |

| AB (high-SES) | 0.21 (0.17, 0.24)* | <0.001 | 0.28 (0.24, 0.31)* | <0.001 | 0.20 (0.17, 0.24)* | <0.001 |

| C1 | 0.10 (0.05, 0.14)* | <0.001 | 0.13 (0.09, 0.17)* | <0.001 | 0.12 (0.08, 0.16)* | <0.001 |

| C2 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| DE (low-SES) (ref) | ||||||

| Familiarity with mental health | ||||||

| Self | 0.77 (0.71, 0.83)* | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.80, 0.91)* | <0.001 | 0.82 (0.77, 0.87)* | <0.001 |

| Other | 0.44 (0.41, 0.47)* | <0.001 | 0.55 (0.52, 0.58)* | <0.001 | 0.56 (0.52, 0.59)* | <0.001 |

| None (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Region n (%) | ||||||

| North East | 0.15 (0.07, 0.23)* | <0.001 | 0.33 (0.26, 0.40)* | <0.001 | 0.22 (0.14, 0.30)* | <0.001 |

| North West | 0.13 (0.07, 0.18)* | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.21, 0.32)* | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.20, 0.32)* | <0.001 |

| York and Hum | 0.19 (0.13, 0.26)* | <0.001 | 0.33 (0.27, 0.39)* | <0.001 | 0.31 (0.24, 0.37)* | <0.001 |

| East Midlands | 0.14 (0.07, 0.20)* | <0.001 | 0.20 (0.14, 0.26)* | <0.001 | 0.20 (0.13, 0.26)* | <0.001 |

| West Midlands | 0.09 (0.03, 0.15)* | 0.002 | 0.20 (0.14, 0.25)* | <0.001 | 0.19 (0.13, 0.25)* | <0.001 |

| East of England | 0.10 (0.04, 0.16)* | 0.002 | 0.21 (0.16, 0.27)* | <0.001 | 0.18 (0.12, 0.24)* | <0.001 |

| South East | 0.09 (0.03, 0.14)* | 0.001 | 0.19 (0.14, 0.24)* | <0.001 | 0.15 (0.09, 0.20)* | <0.001 |

| South West | 0.14 (0.08, 0.21)* | <0.001 | 0.30 (0.24, 0.36)* | <0.001 | 0.18 (0.12, 0.24)* | <0.001 |

| London (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Statistically significant at P < 0.05 level.

Figure 1.

Marginal estimates of stigma-related knowledge (MAKS), attitudes (CAMI) and desire for social distance (RIBS intended behaviour) by year (95% CIs)

Changes in mental health-related public attitudes

There have been significant improvements on the CAMI scale every year since 2013 compared with 2008 (table 2). Participants scored 0.32 (0.26, 0.39) SD units higher on the CAMI scale in 2019 compared with those sampled and partaking in 2008, equivalent to an estimated 12.6% of people’s attitudes improving. An interaction between year and age (adjusted Wald test P < 0.001) suggests that the improvement over time differed depending on age group, with the greatest improvements made in those aged under 25 (Supplementary figure S1). As this age group has more negative attitudes than those aged 25–45, this represents some convergence among age groups. An interaction between year and region was also found to be significant (P < 0.001). Supplementary figure S2 shows marginal estimates of the standardized CAMI score were significantly lower in London compared with other regions for the early years of Time to Change. Although they have improved over time showing some convergence among regions, participants in London remain the lowest scorers. There was no significant interaction for sex, ethnicity or socio-economic status. There was a significant improvement between 2017 and 2019 in the CAMI score, with a change in standard deviation unit of 0.08 (0.02, 0.14). This corresponds to more positive attitudes in 3.2% of people.

Changes in public desire for social distance from mental health problems

There have been significant improvements on the RIBS intended behaviour scale every year compared with 2009 except 2011, as shown in table 2. Participants scored 0.29 (0.23, 0.36) SD units higher in 2019 compared with those sampled and taking part in 2009, equivalent to the level of desire for social distance decreasing in 11.6% of people since 2009. There was a significant interaction between year and region similar to that for the CAMI (P < 0.001) as seen in Supplementary figure S3. No other interactions (sex, ethnicity or socio-economic status) were significant. No change in RIBS intended behaviour score was found for 2017–19.

Discussion

The findings indicate that the mental health stigma-related outcomes of knowledge, attitudes and desire for social distance have improved from just prior to the launch of Time to Change’s social marketing campaign in January 2009–19, with similar effect sizes.

Since the change to the target group at the end of 2016 from socio-economic groups B, C1 and C2 to groups C1, C2 and D, and the content change to focus on men, there is evidence for further improvements in mental health-related knowledge and attitudes but not in desire for social distance between 2017 and 2019. However, there is so far no evidence that the differences in stigma outcomes among socio-economic groups or between men and women have narrowed. This may in part be due to relatively low campaign awareness in the target group despite the change in targeting. Market testing of campaign content suggested that women pay more attention than men to content featuring women, men and women pay equal attention to content featuring men. Therefore, content featuring men may avoid any widening of sex differences due to greater improvements among women, rather than closing this gap due to greater improvements among men.

The greater level of stigma in London compared with other regions persists even after controlling for the individual level variables available. Using a 12-item version of the CAMI, similar regional differences were found in the Health Survey for England 2014, a larger and epidemiological survey.24 Again, these differences persisted after adjustment for individual level variables, with some differences becoming more pronounced.25 These differences suggest that other demographical variables or concepts that have not been measured may explain some of the variance. For example, using statistics from the 2011 Census (Table CT0562), the proportion of residents born outside of the UK in London (37%) is far greater compared with England and Wales (9%). Level of education may be associated with the outcomes and region of residence over and above the effect of socio-economic status as controlled for in our model; country of birth and education may therefore represent unmeasured confounders.26 In terms of possible area level factors, there is a higher prevalence of some mental health problems in London compared with the rest of England,27 including a higher prevalence of psychoses in particular.28 This may contribute to the persistence of negative stereotypes, e.g. based on exposure to unfamiliar people who are visibly unwell29 or to local news media stories about episodes of violence committed by people with psychosis.30 Furthermore, unadjusted analysis using the Health Survey for England suggests more negative attitudes in more urban areas.25

Strengths and limitations of the study

The main limitation of this study is our inability to attribute the changes observed, or to estimate the proportion of the changes observed, to the Time to Change programme, given the impossibility of conducting a controlled study. Other temporal trends may contribute to the changes observed. For example, the increased prevalence in anxiety disorders in young women and in adults aged 55–6431 may affect not only familiarity but also extended contact, in this case knowing someone who knows someone with a mental illness. Extended contact can reduce prejudice between ethnic and religious groups14 and so may also be an unmeasured influence on our results. However, in the absence of anti-stigma interventions, attitudes to depression appear unchanged while those to schizophrenia have worsened.32,33 Further, we have previously shown an improvement from the start of Time to Change above the pre-existing trend from 2003 in one of the two factors of the CAMI.34 Finally, there are positive associations between awareness of Time to Change and each of stigma-related knowledge (MAKS); attitudes (CAMI) and intended behaviour (RIBS intended behaviour).35

We calculated sampling errors even though a quota sample was used which violates some statistical assumptions but allowed us to calculate results as if the data were from a probability sample. While probability sampling has been used to measure single aspects of stigma in England at one time point,24,36 no current epidemiological survey has allowed repeated assessment of multiple aspects of stigma over the course of Time to Change. However, the analysis used a nationally representative dataset and the demographic associations we report for attitudes are consistent with those found in the Health Survey for England 2014.24,25

Finally, the survey does not cover specific diagnoses. The public concept of what constitutes a mental illness has widened, based on responses to MAKS items 7–12 that ask about which conditions participants consider as mental illnesses, including stress and grief (which are false).37 While we do not know which conditions participants have in mind when giving their responses to the other items, it is possible that over time respondents include milder or more self-limiting problems. Given the findings suggesting that elsewhere desire for social distance from someone with schizophrenia is increasing, while for depression there is no evidence for change,32,33 this may contribute to more positive attitudes and reduced desire for social distance over time.

Implications

While since 2017 Time to Change has targeted groups with less positive attitudes than previously, i.e. men and lower socio-economic groups, there is so far no evidence that socio-economic, gender or ethnic differences have narrowed. Changes in media used and/or campaign content may be needed to achieve greater awareness and effects in the target group.

We also recommend research to improve the understanding of these pre-existing demographic differences in stigma outcomes, to better understand and address the social processes which influence stigma as measured at the individual level. For example, small area deprivation has been found to be associated with more negative attitudes; however, this relationship was no longer found once individual level factors, particularly education, were included in a multilevel model.26 Educational attainment may not simply be a confounder; however, it may be on the causal pathway whereby greater neighbourhood deprivation leads to poorer educational attainment,38 in turn leading to less positive attitudes. It is concerning that lower socio-economic groups and some ethnic minority groups such as black ethnic minorities have increased risks of both stigmatization towards mental illness and higher prevalence of some mental illnesses.31,39

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at EURPUB online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for collaboration on the evaluation by Sue Baker, Paul Farmer, George Hoare, Jo Loughran and Lisa Muller.

Funding

The TTC evaluation was funded by the UK Government Department of Health and Social Care, Comic Relief and Big Lottery Fund. C.H. was supported by these grants during phases 1–3 of TTC and E.J.R. during phases 2–3. The funding source had no involvement in the study design, data or report writing.

Conflicts of interest: C.H. has received consulting fees from Lundbeck and educational speaker fees from Janssen. E.J.R. and L.P. declare no conflict of interest. No authors participated in the planning or execution of TTC.

Key points

Mental health stigma-related outcomes of knowledge, attitudes and desire for social distance have improved from just prior to the launch of Time to Change’s social marketing campaign in January 2009–19.

Regional differences in stigma have narrowed over time largely due to improvements in London, while improvements among younger adults have led to a narrowing of differences in stigma by age group.

While since 2017, Time to Change has targeted groups with less positive attitudes than previously, i.e. men and lower socio-economic groups, there is so far no evidence that pre-existing socio-economic status, gender or ethnic differences have narrowed.

References

- 1. Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health 2013;103:813–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mai Q, D’Arcy C, Holman J, et al. Mental illness related disparities in diabetes prevalence, quality of care and outcomes: a population-based longitudinal study. BMC Med 2011;9:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wahlbeck K, Westman J, Nordentoft M, et al. Outcomes of Nordic mental health systems: life expectancy of patients with mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2011;199:453–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Social Exclusion Unit Report. Mental Health and Social Exclusion. London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clement S, Brohan E, Sayce L, et al. Disability hate crime and targeted violence and hostility: a mental health and discrimination perspective. J Ment Health 2011;20:219–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Henderson C, Stuart H, Hansson L. Lessons from the results of three national antistigma programmes. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2016;134:3–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Henderson C, Thornicroft G. Stigma and discrimination in mental illness: Time to Change. Lancet 2009;373:1928–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mehta N, Kassam A, Leese M, et al. Public attitudes towards people with mental illness in England and Scotland, 1994-2003 . Br J Psychiatry 2009;194:278–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Evans-Lacko S, Brohan E, Mojtabai R, Thornicroft G. Association between public views of mental illness and self-stigma among individuals with mental illness in 14 European countries. Psychol Med 2012;42:1741–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sampogna G, Bakolis I, Evans-Lacko S, et al. The impact of social marketing campaigns on reducing mental health stigma: results from the 2009-2014 Time to Change programme. Eur Psychiatry 2017;40:116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Henderson C, Robinson E, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Public knowledge, attitudes, social distance and reported contact regarding people with mental illness 2009–2015. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2016;134:23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Corker E, Hamilton S, Robinson E, et al. Viewpoint survey of mental health service users’ experiences of discrimination in England 2008–2014. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2016;134:6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J Pers Soc Psychol 2006;90:751–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Al Ramiah A, Hewstone M. Intergroup contact as a tool for reducing, resolving, and preventing intergroup conflict: evidence, limitations, and potential. Am Psychol 2013;68:527–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. West K, Holmes E, Hewstone M. Enhancing imagined contact to reduce prejudice against people with schizophrenia. Group Process Intergroup Relat 2011;14:407–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Robinson EJ, Henderson C. Public knowledge, attitudes, social distance and reporting contact with people with mental illness 2009-2017. Psychol Med 2018;49:2717–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Evans-Lacko S, Henderson C, Thornicroft G. Public knowledge, attitudes and behaviour regarding people with mental illness in England 2009-2012. Br J Psychiatry 2013;202:s51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Evans-Lacko S, Little K, Meltzer H, et al. Development and psychometric properties of the Mental Health Knowledge Schedule. Can J Psychiatry 2010;55:440–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taylor SM, Dear MJ. Scaling community attitudes toward the mentally ill. Schizophr Bull 1981;7:225–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Evans-Lacko S, Rose D, Little K, et al. Development and psychometric properties of the reported and intended behaviour scale (RIBS): a stigma-related behaviour measure. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2011;20:263–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Star SA. What the Public Thinks about Mental Health and Mental Illness, Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Association of Mental Health, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1952.

- 22. Sauzet O, Breckenkamp J, Borde T, et al. A distributional approach to obtain adjusted comparisons of proportions of a population at risk. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 2016;13:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. StataCorp, 2017.

- 24. Ilic N, Henderson H, Henderson C, et al. Chapter 3. Attitudes towards mental illness. In: Craig R., Fuller E., Mindell J., editors. Health Survey for England 2014: Health, Social Care and Lifestyles. London: Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bhavsar V, Schofield P, Das-Munshi J, Henderson C. Regional differences in mental health stigma-analysis of nationally representative data from the Health Survey for England, 2014. PLoS One 2019;14:e0210834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ingram E, Jones R, Schofield P, Henderson C. Small area deprivation and stigmatising attitudes towards mental illness: a multilevel analysis of Health Survey for England (2014) data. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2019;54:1379–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Digital PCDN. Quality and Outcomes Framework, Prevalence. Achievements and Exceptions Report: 2015-2016. NHS Digital.

- 28. Kirkbride JB, Errazuriz A, Croudace TJ, et al. Incidence of schizophrenia and other psychoses in England, 1950-2009: a systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS One 2012;7:e31660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee EH, Hui CL, Ching EY, et al. Public stigma in China associated with schizophrenia, depression, attenuated psychosis syndrome, and psychosis-like experiences. Psychiatr Serv 2016;67:766–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clement S, Foster N. Newspaper reporting on schizophrenia: a content analysis of five national newspapers at two time points. Schizophr Res 2008;98:178–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, Brugha T, editors. Mental Health and Wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schomerus G, Schwahn C, Holzinger A, et al. Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2012;125:440–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pescosolido BA, Manago B, Monahan J. Evolving public views on the likelihood of violence from people with mental illness: stigma and its consequences. Health Aff 2019;38:1735–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Evans-Lacko S, Corker E, Williams P, et al. Trends in public stigma among the English population in 2003-2013: influence of the Time to Change anti-stigma campaign. Lancet Psychiatry 2014;1:121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Henderson C, Potts L Department of Health Attitudes to Mental Illness Survey Evaluation Report (2008-2019). Report to the funders, 2019.

- 36.National Centre for Social Research British Social Attitudes 2015, 2016.

- 37. Henderson C, Robinson E. Department of Health Attitudes to Mental Illness Survey Evaluation Report (2008-2017). Report to the funders, 2017.

- 38. Garner CL, Raudenbush SW. Neighborhood effects on educational attainment: a multilevel analysis. Sociol Educ 1991;64:251–62. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Qassem T, Bebbington P, Spiers N, et al. Prevalence of psychosis in black ethnic minorities in Britain: analysis based on three national surveys. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015;50:1057–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.