Cutaneous leishmaniasis is a tropical anthropozoonosis caused by the protozoan parasite belonging to the genus Leishmania.[1] The diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis is based on clinical features, supported by epidemiologic data, and laboratory testing. However, with limited healthcare budgets and a large disease burden like ours, dermoscopy is broadening its horizon and is being used in the diagnosis of this infectious disease as well. We hereby report two cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis with a preliminary diagnosis being made dermoscopically followed by parasitologic and histopathologic confirmation.

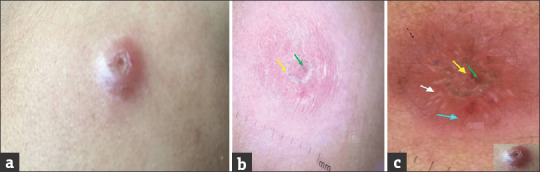

A 15-year-old girl presented with an asymptomatic, single, well-circumscribed nodular lesion on the right forearm which had gradually been increasing in size following insect bite at the same site 4 months ago. On examination, there was a noduloulcerative lesion measuring 3 × 2.5 cm in size with central crusting [Figure 1a]. With a clinical suspicion of cutaneous leishmaniasis, we visualized the lesion using a dermoscope (DermLite DL3N, California, USA) and found the presence of a white starburst pattern and central red area on a pinkish white background. We also observed the presence of comma-shaped and linear vessels [Figure 1b and c].

Figure 1.

(b) Nonpolarized and (c) polarized dermoscopic view (DermLite DL3N, 10×) of cutaneous leishmaniasis showing pinkish white background, central red area representing the ulcer (green arrow) with crust (yellow arrow) chrysalis strands arranged in a white star burst pattern (white arrow), and comma-shaped vessels (blue arrow). Few linear vessels can also be appreciated (black dotted arrow). (a) Solitary noduloulcerative lesion on the forearm

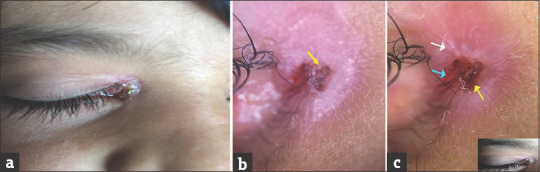

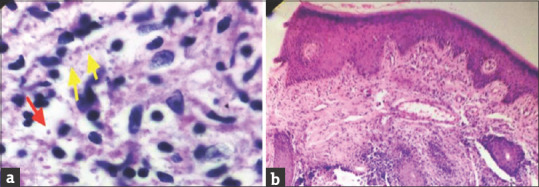

A 6-year-old boy was referred to us from the Department of Ophthalmology in view of nonresponse to antitubercular therapy for a 7-month-old asymptomatic swelling on the nasal aspect of the right eye [Figure 2a]. It was a well-defined, firm, nontender, faintly erythematous plaque measuring 0.5 × 1 cm, with the central area covered with yellowish, loosely adherent crusts. Dermoscopy (using DermLite DL3N) showed central red areas and hyperkeratosis surrounded by a white starburst-like pattern, erythema, and linear vessels [Figure 2b and c]. In both the cases, diagnosis was confirmed by slit-skin smear and histopathology which showed Leishmania donovani bodies and a dermal granulocytic infiltrate composed of epithelioid cells, giant cells, lymphocytes, and macrophages, consistent with the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis [Figure 3].

Figure 2.

(b) Nonpolarized and (c) polarized dermoscopic view (DermLite DL3N, 10×) of cutaneous leishmaniasis showing background erythema, central red area (yellow arrow), star burst pattern of radially arranged chrysalis strands (white arrow), and linear vessels (blue arrow). (a) Crusted plaque on the nasal aspect of right eye

Figure 3.

(a) Slit-skin smear with Leishmania donovani (LD) bodies in the intracellular (yellow arrows) and extracellular spaces (red arrow) ( Giemsa, ×1000). (b) Skin biopsy showing dense inflammation in the dermis along with noncaseating epitheloid granuloma (black arrows) in the dermis (H and E, ×100)

In the present era, dermoscopy has facilitated the rapid diagnosis of many dermatological disorders and has found its utility in cutaneous leishmaniasis as well. Yücel et al. reported dermoscopic findings in 142 lesions from 102 patients. They reported the presence of generalized erythema in 100% cases, yellow tears in 58 lesions, both crust and ulcer in 51 lesions, white starburst-like patterns in 27 lesions, ovoid salmon-colored structures in 19 lesions, and a perilesional hypopigmented halo pattern in 4 lesions.[2] Similar findings have been described by Taheri et al. who additionally noted the presence of milia-like cysts and corkscrew vessels.[3] Yellow tears and perilesional hypopigmentation could not be appreciated in either of our cases. In their study of 26 lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis, Llambrich et al. found coexistence of more than one type of vascular lesion – two in 50% and three or more in 38%.[4] Similar findings were revealed by Dobrev et al.[5] and Nassiri.[6] To the best of our knowledge, no Indian literature exists on the dermoscopic appearance of cutaneous leishmaniasis so far and ours is the first from this part of the globe. We suggest that recognition of dermoscopic features like white star burst pattern (chrysalis crystals) representing collagen and central red areas representing ulceration should be encouraged to aid the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. It may be particularly helpful in patients not consenting for a skin biopsy or in those with extremes of age and as a complementary investigation in other cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bari A, Rahman SB. Many faces of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:23–7. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.38402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yücel A, Günaşti S, Denli Y, Uzun S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: New dermoscopic findings. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:831–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taheri AR, Pishgooei N, Maleki M, Goyonlo VM, Kiafar B, Banihashemi M, et al. Dermoscopic features of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1361–6. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llambrich A, Zaballos P, Terrasa F, Torne I, Puig S, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:756–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobrev HP, Nocheva DG, Vuchev DI, Grancharova RD. Cutaneous leishmaniasis – Dermoscopic findings and cryotherapy. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 2015;57:65–8. doi: 10.1515/folmed-2015-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nassiri A. Dermoscopic features of cutaneous leishmaniasis: Study of 52 lesions. J Am Acad. 2017;76:AB97. [Google Scholar]