Abstract

Background

The course of anxiety disorders during childhood is heterogeneous. In two generations at high or low risk, we described the course of childhood anxiety disorders and evaluated whether parent or grandparent major depressive disorder (MDD) predicted a persistent anxiety course.

Methods

We utilized a multigenerational study (1982–2015), following children (second generation, G2) and grandchildren (third generation, G3) of generation 1 (G1) with either moderate/severe MDD or no psychiatric illness. Psychiatric diagnoses were based on diagnostic interviews. Using group-based trajectory models, we identified clusters of children with similar anxiety disorder trajectories (age 0–17).

Results

We identified 3 primary trajectories in G2 (N=275) and G3 (N=118) cohorts: ‘no/low anxiety disorder’ during childhood (G2=66%; G3=53%), ‘non-persistent’ with anxiety during part of childhood (G2=16%; G3=21%), and ‘persistent’ (G2=18%; G3=25%). Childhood mood disorders and substance use disorders tended to be more prevalent in children in the persistent anxiety trajectory. In G2 children, parent MDD was associated with an increased likelihood of being in the persistent (84%) or non-persistent trajectory (82%) vs. no/low anxiety trajectory (62%). In G3 children, grandparent MDD, but not parent, was associated with an increased likelihood of being in the persistent (83%) vs. non-persistent (48%) and no/low anxiety (51%) trajectories.

Conclusion

Anxiety trajectories move beyond what is captured under binary, single time-point, measures. Parent or grandparent history of moderate/severe MDD may offer value in predicting child anxiety disorder course, which could help clinicians and caregivers identify children needing increased attention and screening for other psychiatric conditions.

Keywords: Anxiety disorders, child, depressive disorder, major, parents, grandparents, prediction, trajectories

BACKGROUND

Anxiety disorders often begin in childhood and are among the most prevalent psychiatric conditions in children and adolescents with roughly a third of individuals having an anxiety disorder by the end of childhood.(Kessler RC et al., 2005; Merikangas KR et al., 2010) Globally and in the United States, anxiety disorders are a leading cause of years lived with disability for children and adolescents.(Global Burden of Disease Pediatrics et al., 2016) Compared to those without childhood anxiety, youth with anxiety disorders have worse health, financial, and interpersonal outcomes(Copeland, Angold, Shanahan, & Costello, 2014) and childhood anxiety disorders increase the risk for later other psychiatric disorders.(Bittner et al., 2007; Essau, Lewinsohn, Olaya, & Seeley, 2014; Woodward & Fergusson, 2001) However, there is wide heterogeneity in the onset and progression of anxiety disorders through the life-course. While anxiety disorders can be chronic and persistent, anxiety disorders can remit or wax and wane across childhood and not persist into adulthood.(Asselmann & Beesdo-Baum, 2015; Beesdo-Baum & Knappe, 2012; Ginsburg et al., 2018; Wittchen, Lieb, Pfister, & Schuster, 2000)

Identifying distinct courses, or trajectories, of anxiety disorders in childhood provides information beyond binary or cross-sectional classifications of anxiety disorders, informing our understanding of the heterogeneous nature of anxiety disorders. Prior investigations have described trajectories of anxiety symptoms in part of childhood,(Ahlen & Ghaderi, 2019; Allan et al., 2014; Battaglia et al., 2016; Betts et al., 2016; Crocetti, Klimstra, Keijsers, Hale, & Meeus, 2009; Duchesne, Larose, Vitaro, & Tremblay, 2010; Feng, Shaw, & Silk, 2008; Legerstee et al., 2013; Olino, Klein, Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 2010; Olino, Stepp, Keenan, Loeber, & Hipwell, 2014; Zerwas, Von Holle, Watson, Gottfredson, & Bulik, 2014) with the majority of research focusing on anxiety symptoms across a few time points in childhood. Moreover, we can identify predictors of anxiety disorder trajectories rather than predictors of anxiety onset or anxiety at a singular point in time. Identifying predictors of more persistent, chronic courses of anxiety disorders can help inform prognosis and target intervention efforts to those at a heightened risk for adverse outcomes.(Asselmann & Beesdo-Baum, 2015; Beesdo-Baum & Knappe, 2012; Ginsburg et al., 2018; Ohannessian, Milan, & Vannucci, 2017)

Parent depression increases the risk of pediatric anxiety(Cote et al., 2018; Lieb, Isensee, Hofler, Pfister, & Wittchen, 2002; Warner, Weissman, Mufson, & Wickramaratne, 1999) and through this ongoing high-risk, three-generational study, we previously highlighted an increased risk of depression and other psychiatric disorders in individuals with parent and grandparent depression.(Weissman et al., 2016; Weissman, Leckman, Merikangas, Gammon, & Prusoff, 1984) However, the association between parent depression and the course of anxiety through childhood is less clear.(Batelaan, Rhebergen, Spinhoven, van Balkom, & Penninx, 2014; Feng et al., 2008; Legerstee et al., 2013; Olino et al., 2010; Zerwas et al., 2014) Since parent psychiatric history is often obtained at child assessment, if parent depression predicts anxiety course, it could have high clinical utility.

The multi-generational cohort provides a unique opportunity to expand upon past analyses by studying anxiety disorder trajectories in two generations, by examining trajectories across all of childhood, and by determining whether family depression predicts anxiety course with family diagnoses based on detailed clinical interviews. Therefore, in the three-generation study with clinical psychiatric diagnoses, we aimed to describe the course of childhood anxiety disorders separately in two generations and to determine if parent or grandparent major depressive disorder (MDD) predicted a more persistent anxiety course.

METHODS

Participants, study population

The three-generation cohort began with adults (probands, generation one, G1) with moderate to severe MDD seeking treatment at outpatient facilities (high-risk) and adults from the same community with no MDD history and no psychiatric history (low-risk).(Weissman et al., 2016; Weissman et al., 1987; Weissman et al., 1984) Adults with history of primary substance use disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and antisocial personality disorder, were excluded from either group. Adults were of white race and ethnicity, common in genetic studies of the time to reduce heterogeneity. The offspring, and later the grandchildren, of the probands were invited to participate in the study as they aged in. Assessments were completed at study start (year 0, 1982) and at assessment years 2, 10, 20, 25, and 30. Offspring and grandchildren of probands with MDD constituted the high-risk group; offspring and grandchildren of probands without MDD constituted the low-risk group.

For the study presented here, we focus on the biological offspring (second generation, G2) and grandchildren (third generation, G3) of the probands. For G2, data collection began at study start (year 0) and for G3 at assessment year 10. We restricted our sample to G2 offspring (96%) and G3 grandchildren (61%) with at least one assessment after age 17 to restrict our analysis to persons with complete anxiety disorder history during childhood. For G3, one additional individual was excluded due to missing anxiety disorder offset information for the majority of childhood. This research was approved by the New York State Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board.

Anxiety disorder clinical measures

Anxiety disorder episodes were defined based on diagnostic interviews conducted at each assessment using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia–Lifetime (SADS-L) for adults(Mannuzza, Fyer, Klein, & Endicott, 1986) and Kiddie-SADS (K-SADS) for children aged 6–17 years (assessment year 10: K-SADS-e, assessment years 20, 25, 30: K-SADS-PL).(Kaufman et al., 1997; Orvaschel, Puig-Antich, Chambers, Tabrizi, & Johnson, 1982) In the diagnostic interviews, participants (child or parent) were asked to report on psychiatric disorders since last assessment, or since birth if they had no prior assessment. Therefore, while participants are not interviewed every year, they are asked to recall past episodes, collectively providing a complete psychiatric history since birth. In our final sample, 39% of G2 and 82% of G3 had one assessment in childhood and one assessment after age 17 that together constituted their childhood (ages 0–17) anxiety disorder history.

Anxiety disorders included specific phobia, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social phobia, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD was not evaluated until assessment year 20. Interview administrators were blind to the clinical status of all generations and anxiety disorder diagnoses were based on a best estimate procedure completed by experienced mental health professionals who used all available information, were not involved in interviewing, and were blind to clinical status of previous generations.(Leckman, Sholomskas, Thompson, Belanger, & Weissman, 1982) We included anxiety disorder episodes rated definite or probable based on the best estimate; definite diagnoses were given when all anxiety disorder diagnostic criteria were met and probable when more than half of major diagnostic criteria were met.(Leckman et al., 1982)

For each anxiety disorder episode, we used date of episode onset and episode duration to determine age of onset and offset per episode. For each person we grouped reported anxiety disorder episodes together and created binary indicators for whether he or she had an anxiety disorder at each age from 0 to 17. For example, if an individual had one episode onset at age 5 with offset at 8.5 and a second episode onset at age 12.5 with offset at 16.8, we considered this individual to have an anxiety disorder from ages 5–8 and 12–16.

Additional childhood measures

We included measures for childhood onset MDD, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, substance (alcohol or drug) use disorder, and disruptive behavior (includes ADHD). Psychiatric conditions were classified as childhood onset when episode onset was before age 18. As with anxiety disorders, these diagnoses were based on the SADS or K-SADS and the best-estimate procedure.

Grandparent and parent measures

For G2 children, we had information on parent psychiatric diagnoses and for G3 children we had parent and grandparent psychiatric diagnoses; diagnoses were based on best-estimates. To have a similar MDD severity thresholds for parent MDD measures across generations, for G3 children we added a previously used impairment criterion based on the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) to the parent MDD measure.(Weissman et al., 2016) Individuals with MDD and a mean GAS score of ≤70 across assessment years were considered to have moderate/severe MDD. The GAS was administered at each assessment and provides an estimate on current functioning; scores range from 0–100 and higher scores indicate better functioning.(Endicott, Spitzer, Fleiss, & Cohen, 1976)

Statistical analysis

We described G2 and G3 cohorts stratified by proband/G1 high or low risk. We used group-based trajectory models to identify clusters of individuals with similar anxiety disorder status from birth through age 17 with “Proc Traj”, an add-on package to SAS version 9.4 available for free download.(http://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/bjones/download.htm)(Twisk & Hoekstra, 2012) In group-based trajectory models, maximum likelihood was used to estimate model parameters and probability of membership into each group estimated using a multinomial logistic model without predictors.(Jones & Nagin, 2007; Jones, Nagin, & Roeder, 2001) We estimated models for up to six groups; final number of groups was decided based on clinical interpretability, size of smallest group, and model fit using Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC).(Jones et al., 2001) We began with a quadratic term (order=2) and model fit did not improve when altering to cubic. Children were placed into the most-likely trajectory group and we described children in each group. We estimated entropy as a measure of uncertainty in classification, with values closer to one indicating improved classification.(Minjung, Jeroen, Zsuzsa, Thomas, & Lee, 2016; Nagin & Odgers, 2010) For a secondary analysis, we ran the trajectory analysis separately in high and low risk families.

For G2, parent MDD, and for G3, grandparent MDD and parent MDD were evaluated as predictors of belonging to the trajectory group. We estimated the odds ratio (OR) for the association between parent and/or grandparent MDD with anxiety disorder trajectory accounting for family clustering.

Sensitivity analyses

We recreated trajectory models excluding specific phobia episodes and examined parent or grandparent MDD as a predictor in these trajectories without specific phobia. We also repeated analyses excluding PTSD and OCD episodes to account for their exclusion in the DSM-5 anxiety disorder category. Given clustered data with multiple offspring per parent, we violate independence assumptions for group-based trajectory models. Therefore, we evaluated trajectories in 10 samples, each randomly selecting one offspring per parent, to determine if primary anxiety trajectories remained consistent.

RESULTS

Study populations: Second (G2) and third (G3) generations

The G2 cohort included 275 children, 69% from a high-risk family, and the G3 cohort 118 children, 58% from a high-risk family (Table 1). In G2, the median age at first interview was 20 years (IQR:15–24) and 41 (32–49) at last interview and in G3, 10 years (8–15) and 23 years (21–28). Forty-four percent of G2 children and 50% of G3 children had an anxiety disorder before age 18, with 5 years the median age onset (Table 1). In G2, separation anxiety disorder (48%) and specific phobia (46%) were the most common childhood anxiety disorders, compared to specific phobia (63%) and social phobia (36%) in G3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of G2 and G3 offspring stratified by family high-risk status (G1 moderate to severe MDD)

| Second generation (G2) children | Third generation (G3) children | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N=275 | High risk N=190 | Low risk N=85 | Total N=118 | High risk N=69 | Low risk N=49 | |

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Number of families | 90 | 64 | 26 | 40 | 28 | 12 |

| Female | 145 (53) | 98 (52) | 47 (55) | 59 (50) | 34 (49) | 25 (51) |

| Anxiety disorders, before age 18 | ||||||

| Definite or probable anxiety disorder | 122 (44) | 97 (51) | 25 (29) | 59 (50) | 39 (57) | 20 (41) |

| Separation anxiety | 59 (21) | 43 (23) | 16 (19) | 6 (5) | 5 (7) | 1 (2) |

| Specific phobia | 56 (20) | 45 (24) | 11 (13) | 37 (31) | 25 (36) | 12 (24) |

| GAD | 34 (12) | 29 (15) | 5 (6) | 3 (3) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Panic disorder or agoraphobia | 17 (6) | 17 (9) | 0 (0) | 13 (11) | 11 (16) | 2 (4) |

| OCD | 10 (4) | 9 (5) | 1 (1) | 6 (5) | 5 (7) | 1 (2) |

| Social phobia | 25 (9) | 20 (11) | 5 (6) | 21 (18) | 16 (23) | 5 (10) |

| PTSD | - | - | - | 9 (8) | 6 (9) | 3 (6) |

| Multiple anxiety disorders | 51 (19) | 43 (23) | 8 (9) | 19 (16) | 17 (25) | 2 (4) |

| Age at anxiety onset, median (IQR), years | 5 (4–9) | 5 (4–10) | 5 (4–7) | 5 (5–10) | 5 (5–6) | 9 (4–13) |

| Psychiatric disorders, before age 18 | ||||||

| Any mood disorder | 125 (45) | 100 (53) | 25 (29) | 38 (32) | 27 (39) | 11 (22) |

| MDD | 87 (32) | 74 (39) | 13 (15) | 18 (15) | 11 (16) | 7 (14) |

| Dysthymia | 78 (28) | 60 (32) | 18 (21) | 15 (13) | 11 (16) | 4 (8) |

| Alcohol or drug use disorder | 71 (26) | 53 (28) | 18 (21) | 20 (17) | 13 (19) | 7 (14) |

| Disruptive disorder | 89 (32) | 69 (36) | 20 (24) | 23 (19) | 14 (20) | 9 (18) |

| Grandparent & parent MDD history, ever† | ||||||

| Grandparent and parent | - | - | - | 21 (18) | 21 (30) | - |

| Grandparent, no parent | - | - | - | 48 (41) | 48 (70) | - |

| Parent, no grandparent | - | - | - | 12 (10) | - | 12 (24) |

| No parent, no grandparent | - | - | - | 37 (31) | - | 37 (76) |

| Parent psychiatric history, ever | ||||||

| MDD (moderate/severe)† | 195 (71) | 190 (100) | 5 (6)‡ | 33 (28) | 21 (30) | 12 (24) |

| Any MDD (no impairment criterion) | - | - | - | 86 (73) | 54 (78) | 32 (65) |

| Any mood disorder | 199 (72) | 190 (100) | 9 (11) | 97 (82) | 60 (87) | 37 (76) |

| Anxiety disorder | 83 (30) | 76 (40) | 7 (8) | 95 (81) | 56 (81) | 39 (80) |

| Alcohol or drug use disorder | 107 (39) | 95 (50) | 12 (14) | 78 (66) | 52 (75) | 26 (53) |

MDD: Major depressive disorder; OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; GAD: generalized anxiety disorder

Parent (G2) MDD measure with impairment criterion applied

Five G1 probands reported MDD at later ages

Childhood anxiety disorder trajectories

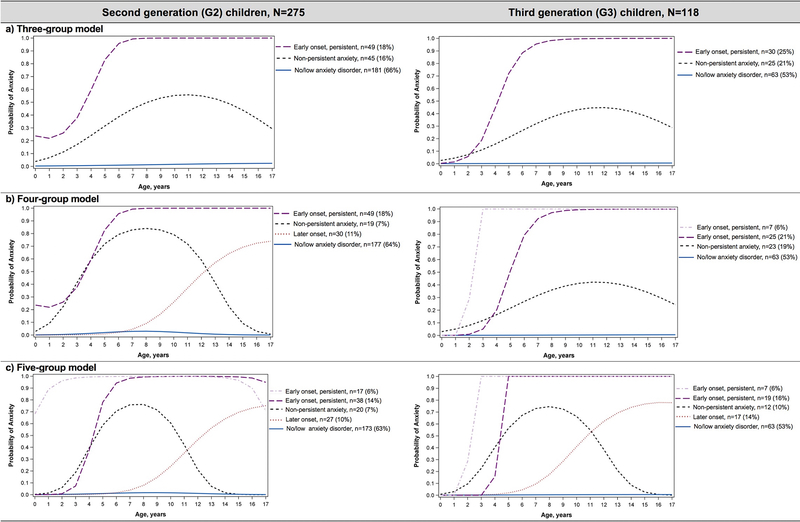

The trajectory models for 3–5 groups are displayed for G2 and G3 in Figure 1. Model fit improved with each additional group allowed; we focus on the 3-group trajectory model given limited sample size, particularly in G3 trajectories. The three identified trajectories of childhood anxiety disorders were similar between G2 and G3 children; 53% of G3 children (G2=66%) were in a trajectory labeled ‘no/low anxiety disorder’, 21% (16%) in a ‘non-persistent’ trajectory with anxiety disorders during part of childhood, and 25% (18%) in a ‘persistent’ trajectory (Figures 1). The estimated entropy for G2 and G3 was >0.95. The mean (and range) of posterior probabilities for group membership in G2 were: persistent anxiety=1.00 (0.94–0.99), non-persistent=0.97 (0.55–1.00), and no/low anxiety=0.99 (0.61–0.99) and for G3: 1.00 (0.97–1.00), 0.98 (0.75–1.00), and 0.99 (0.89–1.00), respectively. Six persons in G2 and two in G3 had a posterior probability <0.8.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of reported anxiety disorder episodes during childhood (0–17 years). G2—model fit: 3-group model (BIC: −1,157, AIC: −1,134), 4-group model (BIC: −1,040, AIC: −1,013), 5-group model (BIC: −940, AIC: −906); G3—model fit: 3-group model (BIC: −495, AIC: −480), 4-group model (BIC: −489, AIC: −468), 5-group model (BIC: −442, AIC: −415). AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criterion

Children in the persistent trajectory had one anxiety disorder spanning most of childhood or multiple anxiety disorders with varying ages of onset and offset. In G2 children placed in the persistent anxiety trajectory (n=49), 17 had one anxiety disorder across childhood (14 with specific phobia), 25 had specific phobia with another anxiety disorder, and seven had at least two other anxiety disorders with at least one anxiety disorder by age 6. In G3 children placed in the persistent anxiety trajectory (n=30), 15 had one anxiety disorder across childhood (10 with specific phobia), six had specific phobia with another anxiety disorder, and nine had at least two other anxiety disorders with all but one having an anxiety disorder onset before age 10 and another onset after age 10.

Table 2 (G2) and Table 3 (G3) display characteristics of children by anxiety trajectory. Mood disorders, disruptive disorders, and substance use disorders tended to be more prevalent during childhood in the persistent anxiety trajectory than the non-persistent trajectory and the no/low anxiety trajectory. Differences were more pronounced in the G3 cohort.

Table 2.

Characteristics of G2 children in each anxiety disorder trajectory group

| G2 children by anxiety disorder trajectory | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early onset, persistent anxiety n=49 (18%) | Non-persistent anxiety n=45 (16%) | No/low anxiety n=181 (66%) | ||||

| No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | |

| High risk group (G1 moderate/severe MDD) | 41 | 84 (70–93) | 37 | 82 (68–92) | 112 | 62 (54–69)*,** |

| Parent (G1) psychiatric disorders | ||||||

| MDD prior to G2 birth | 19 | 39 (25–54) | 15 | 33 (20–49) | 55 | 30 (24–38) |

| Any mood disorder, ever | 41 | 84 (70–93) | 40 | 89 (76–96) | 118 | 65 (58–72)*,** |

| Anxiety disorder, ever | 14 | 29 (17–43) | 18 | 40 (26–56) | 51 | 28 (22–35) |

| Alcohol or drug use disorder, ever | 23 | 47 (33–62) | 20 | 44 (30–60) | 64 | 35 (28–43) |

| G2 characteristics | ||||||

| Female | 33 | 67 (52–80) | 29 | 64 (49–78) | 83 | 46 (38–53)*,** |

| Anxiety disorder(s) in childhood† | ||||||

| Specific phobia | 39 | 80 (66–90) | 13 | 29 (16–44)** | 4 | 2 (1–6)*,** |

| Social phobia | 16 | 33 (20–48) | 9 | 20 (10–35) | 0 | - |

| Panic disorder or agoraphobia | 8 | 16 (7–30) | 6 | 13 (5–27) | 3 | 2 (0–5)*,** |

| OCD | 7 | 14 (6–27) | 1 | 2 (0–12) | 2 | 1 (0–4)** |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 20 | 41 (27–56) | 25 | 56 (40–70) | 14 | 8 (4–13)*,** |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 12 | 24 (13–39) | 12 | 27 (15–42) | 10 | 6 (3–10)*,** |

| More than one anxiety disorder | 32 | 65 (50–78) | 16 | 36 (22–51)** | 3 | 2 (0–5)*,** |

| Years with anxiety in childhood | 14 (13–17) | 6 (4–9)** | 0 (0–0)*,** | |||

| Psychiatric disorders, onset <18yrs | ||||||

| Any mood disorder | 33 | 67 (52–80) | 27 | 60 (44–74) | 65 | 36 (29–43)*,** |

| MDD | 24 | 49 (34–64) | 19 | 42 (28–58) | 44 | 24 (18–31)*,** |

| Dysthymia | 17 | 35 (22–50) | 20 | 44 (30–60) | 41 | 23 (17–29)* |

| Disruptive disorder | 20 | 41 (27–56) | 13 | 29 (16–44) | 56 | 31 (24–38) |

| Alcohol or drug use disorder | 19 | 39 (25–54) | 11 | 24 (13–40) | 41 | 23 (17–29)** |

MDD: Major depressive disorder; OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder; G1: first generation (proband); G2: second generation

p-value<=0.05 compared to non-persistent trajectory

p-value<=0.05 compared to early/persistent trajectory

28 children placed in the ‘no/low anxiety’ trajectory had an anxiety disorder, duration: 1 year (n=12), 2 years (n=14), 3 years (n=2); No PTSD cases

Table 3.

Characteristics of G3 children in each anxiety disorder trajectory group

| G3 children by anxiety disorder trajectory | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early onset, persistent anxiety n=30 (25%) | Non-persistent anxiety n=25 (21%) | No/low anxiety n=63 (53%) | ||||

| No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | |

| High risk group (G1 moderate/severe MDD) | 25 | 83 (65–94) | 12 | 48 (28–69)** | 32 | 51 (38–64)** |

| Grandparent (G1), parent (G2) MDD† | ||||||

| Parent and grandparent | 9 | 30 (15–49) | 6 | 24 (9–45) | 6 | 10 (4–20)** |

| Grandparent only | 16 | 53 (34–72) | 6 | 24 (9–45)** | 26 | 41 (29–54) |

| Parent only | 0 | - | 3 | 12 (3–31) | 9 | 14 (7–25)** |

| Neither parent or grandparent | 5 | 17 (6–30) | 10 | 40 (21–61) | 22 | 35 (23–47) |

| Parent (G2) psychiatric disorders, ever | ||||||

| MDD (moderate/severe)† | 9 | 30 (15–49) | 9 | 36 (18–57) | 15 | 24 (14–36) |

| Any MDD (no impairment criterion) | 22 | 73 (54–88) | 18 | 72 (51–88) | 46 | 73 (60–83) |

| Any mood disorder | 28 | 93 (78–99) | 21 | 84 (64–95) | 48 | 76 (64–86)** |

| Anxiety disorder | 25 | 83 (65–94) | 23 | 92 (74–99) | 47 | 75 (62–85) |

| Alcohol or drug use disorder | 21 | 70 (51–85) | 16 | 64 (43–82) | 41 | 65 (52–77) |

| G2 characteristics | ||||||

| Female | 16 | 53 (34–72) | 13 | 52 (31–72) | 30 | 48 (35–61) |

| Anxiety disorder(s) in childhood‡ | ||||||

| Specific phobia | 22 | 73 (54–88) | 14 | 56 (35–76) | 1 | 2 (0–9)*,** |

| Social phobia | 12 | 40 (23–59) | 9 | 36 (18–57) | 0 | - |

| Panic disorder or agoraphobia | 9 | 30 (15–49) | 4 | 16 (5–36) | 0 | - |

| PTSD | 4 | 13 (4–31) | 3 | 12 (3–31) | 2 | 3 (0–11) |

| OCD | 5 | 17 (6–35) | 1 | 4 (0–20) | 0 | - |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 5 | 17 (6–35) | 0 | - | 1 | 2 (0–9)** |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 3 | 10 (2–27) | 0 | - | 0 | - |

| More than one disorder | 15 | 50 (31–69) | 4 | 16 (5–36)** | 0 | - |

| Years with anxiety in childhood | 13 (13–14) | 5 (3–7)** | 0 (0–0)*,** | |||

| Psychiatric disorders, onset <18yrs | ||||||

| Any mood disorder | 18 | 60 (41–77) | 10 | 40 (21–61) | 10 | 16 (8–27)*,** |

| MDD | 5 | 17 (6–35) | 6 | 24 (9–45) | 7 | 11 (5–22) |

| Dysthymia | 9 | 30 (15–49) | 4 | 16 (5–36) | 2 | 3 (0–11)*,** |

| Disruptive disorder | 10 | 33 (17–53) | 4 | 16 (5–36) | 9 | 14 (7–25)** |

| Alcohol or drug use disorder | 9 | 30 (15–49) | 3 | 12 (3–31) | 8 | 13 (6–23)** |

MDD: Major depressive disorder; OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; G1: first generation (proband); G2: second generation; G3: third generation

p-value<=0.05 compared to non-persistent trajectory

p-value<=0.05 compared to early/persistent trajectory

Parent (G2) MDD measure with impairment criterion applied

4 children placed in the ‘no/low anxiety’ trajectory had an anxiety disorder reported to last 1 year

Under the 5-group trajectory model (Figure 1), sample size is limited within trajectories, but a later onset course and early onset remitting course are revealed. Supplemental Table S1 (G2) and Table S2 (G3) display characteristics of children under the 5-group trajectory model.

Parent, grandparent MDD as a predictor

G2 children with parent MDD (high-risk) had an increased likelihood of membership in the persistent-anxiety trajectory (84%, OR=3.16, p<0.05) compared to the no/low anxiety trajectory (62%) (Table 2), with no difference between the non-persistent and persistent trajectories. However, there was no difference between any trajectories when evaluating parent MDD before child birth.

In G3, children with grandparent MDD (high-risk) had an increased likelihood of membership in the persistent-anxiety trajectory (83%) compared to the no/low anxiety (51%, OR=4.85, p<0.05) and non-persistent (48%, OR=5.42, p<0.05) trajectories (Table 2). Parent MDD was not associated with trajectory membership. G3 children with no parent and no grandparent MDD history had a decreased likelihood of membership in the persistent-anxiety trajectory (17%) compared to the no/low anxiety (35%, OR=0.37) and non-persistent (40%, OR=0.30) trajectories (Table 3). In all trajectories, the majority of G3’s parents had history of anxiety disorders (range across trajectories: 75–92%), mood disorder (76–93%), or substance abuse (65–70%).

High vs. low risk stratification

When stratifying G2 and G3 by high or low risk status, identified trajectories were similar (no/low anxiety, non-persistent, persistent). In the low-risk strata, a lower proportion of children were allocated into a persistent trajectory (G2=5%; G3=10%) than children from a high-risk family (G2=22%; G3=36%), Table S3 (G2), Table S4 (G3). Of note, within high-risk G3 children, a higher proportion in the persistent anxiety trajectory had a mood disorder during childhood (72%) than children in non-persistent (33%) and no/low anxiety (16%) trajectories; differences were present, but less pronounced in high-risk G2 children (71%, 61%, 43%).

Sensitivity analyses

Excluding specific phobia episodes, a higher proportion of G2 and G3 children fell into the no/low anxiety trajectory (74–76%) and fewer in the persistent trajectory (9–10%). In G3 children, findings by parent and grandparent MDD were similar; in G2 children, parent MDD (high-risk) no longer significantly predicted anxiety trajectory but remained lowest in the no/low anxiety trajectory. Excluding PTSD and OCD, 3-group trajectory models and associations of parent or grandparent MDD with trajectories were consistent in G2 and G3. Lastly, when drawing ten random samples of one offspring per family, (G2: n=90; G3: n=67), three trajectories were consistent, with variation in the non-persistent trajectory appearing in either a bell-curve or skewed towards later childhood. In G2, the proportion with parent MDD remained higher in the persistent (range across 10 samples: 75–100%) and non-persistent (75–90%) trajectories than the no/low anxiety trajectory (57–68%). In G3, the proportion with grandparent MDD (high-risk family) remained highest in the persistent (range: 79–95%) trajectory compared to the non-persistent (55–83%) and no/low anxiety (49–57%) and the proportion with parent MDD was only slightly lower in the no/low anxiety (15–26%) trajectory than persistent (22–37%) and non-persistent (20–50%) trajectories.

DISCUSSION

We identified courses of childhood anxiety disorders in two generations and highlighted pertinent distinctions between children in each course. Children with more persistent anxiety may need increased observation for other psychiatric illnesses as a higher proportion of children in the persistent anxiety disorder trajectory reported other psychiatric disorders during childhood than those in non-persistent or no/low anxiety trajectories. Parent or grandparent MDD history appears to offer some value in predicting child anxiety disorder trajectory and may help identify children at heightened risk; however, discrepancies were present between second and third-generation cohorts.

Anxiety disorder trajectories

The identified trajectories highlight heterogeneity in the course of childhood anxiety and move beyond what is captured under binary or cross-sectional childhood measures. Prior work highlighted that not all childhood anxiety disorders persist into late adolescence or early adulthood(Betts et al., 2016; Bittner et al., 2007; Ginsburg et al., 2018; Wittchen et al., 2000; Woodward & Fergusson, 2001) and identified anxiety symptom trajectories; however, the age range evaluated was typically narrower. For example, in girls 5–12 years(Zerwas et al., 2014) and 10–17 years,(Olino et al., 2014) anxiety symptom trajectories included low, high-decreasing, and high-increasing groups. Comparable trajectories were found in separation anxiety disorder (high-increasing, high-declining, low-persistent, low-increasing) from age 1.5 to 6 years,(Battaglia et al., 2016) in broad anxiety symptom trajectories from ages 8–14 years(Ahlen & Ghaderi, 2019) and in children aged 6–12 years.(Duchesne et al., 2010) Differences in anxiety symptom trajectories between boys and girls have also been described.(Legerstee et al., 2013) In joint anxiety and depression trajectories from age 14–30 years, trajectories included no anxiety, increasing anxiety, anxiety decreasing by early adulthood, and anxiety increasing in early adulthood;(Olino et al., 2010) patterns extending past what we observed through age 17. While we observed high posterior probabilities and entropy,(Nagin & Odgers, 2010) identified trajectories are based on reported anxiety disorder episode onset and offset and trajectories and do not capture all individual variation. Similarities with prior literature and across both generations provide support for these varying courses. Together, details on the heterogeneous course of anxiety disorders can inform clinicians and families making treatment decisions and can be extended in future research to examine outcomes and early predictors of anxiety disorder trajectories.

Parent and grandparent MDD

Prior work yielded varied results on whether parent depression predicted anxiety trajectories. Maternal depression, measured with CES-D when the child was 36-months, predicted whether young girls were in a low vs. high anxiety symptom trajectory through age 12 years, but did not significantly predict high-decreasing vs. high-increasing trajectories.(Zerwas et al., 2014) In young boys, maternal depression during the child’s first years of life predicted membership in a high-increasing vs. low anxiety symptom trajectory.(Feng et al., 2008) Parent lifetime depression, measured through structured clinical interviews, was not statistically significantly associated with belonging to a persistent anxiety trajectory compared to a declining anxiety trajectory or a low depression and anxiety trajectory.(Olino et al., 2010) Parent history of internalizing problems was slightly higher for girls in a high-increasing-anxiety symptom trajectory (32%) vs. mid-symptom declining (23%) and for boys in high-declining (24%) vs. mid-stable trajectory (15%).(Legerstee et al., 2013) In young children, maternal depression predicted belonging to a high-increasing depression/anxiety symptom trajectory vs. a moderate-increasing trajectory(Cote et al., 2009) and to a separation anxiety disorder high-increasing vs. low-persistent trajectory.(Battaglia et al., 2016)

In our sample of second-generation children, parent MDD (high-risk family) predicted belonging to the persistent or non-persistent anxiety trajectory compared to the no/low anxiety trajectory, but did not distinguish between the non-persistent and persistent trajectories. In third-generation children, parent MDD did not predict anxiety disorder trajectory; however, grandparent MDD (high-risk family) predicted membership into the persistent anxiety disorder trajectory.

Differences between results could be related to differing measures of parent depression, depression severity, and timing of collection. In prior work, duration of maternal depression episode, but not current maternal symptom severity and number of episodes, was associated with child’s internalizing scores.(Foster et al., 2008) Our binary ‘parent MDD’ variable in G2 children measured parents with moderate to severe, treatment resistant MDD vs. parents without MDD and other psychiatric disorders. Whereas, in G3 children ‘parent MDD’ measured MDD with impairment vs. parents with and without other psychiatric conditions, perhaps why grandparent MDD was a stronger predictor than parent MDD in G3. While variable, findings warrant collecting family (including grandparent) history of moderate/severe depression when children present with anxiety disorders to inform care.

Childhood psychiatric comorbidities

Comorbid psychiatric disorders are common in children with anxiety disorders and prior studies, including previous work in this cohort, have described the association between childhood anxiety disorders and an increased likelihood of developing other psychiatric conditions, particularly depression.(Bittner et al., 2007; Copeland, Shanahan, Costello, & Angold, 2009; Essau, Lewinsohn, Lim, Ho, & Rohde, 2018; Warner, Wickramaratne, & Weissman, 2008; Weissman et al., 1999; Woodward & Fergusson, 2001) Girls in a high-increasing anxiety symptom trajectory in adolescence had an increased likelihood of MDD in early adulthood compared to girls in a mid-symptom trajectory.(Legerstee et al., 2013) Relatedly, childhood mood disorders and substance use disorders were prevalent in children with persistent anxiety disorders compared to children with non-persistent anxiety disorders. Even within high-risk families, differences in childhood mood disorder prevalence were apparent across the anxiety trajectories. Proper treatment of anxiety disorders and careful observation for psychiatric comorbidities may be particularly warranted in children with anxiety disorders persisting into late childhood.

Limitations

The original study selection was based on identifying offspring with high or low MDD risk; as such, prevalence estimates of children falling into each trajectory may differ from population-based samples and many psychiatric diagnoses are more prevalent than general samples. Relatedly, our sample was all white from a selected US region, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Examining trajectories in under-represented populations is essential to inform care and treatment of pediatric anxiety disorders across diverse populations. Sample size limited detection of differences between trajectory groups. Our analysis was limited to persons with complete childhood psychiatric history; however, trajectories were similar when we included cases missing anxiety disorder information in later childhood. Patient details were collected on onset and duration of each psychiatric disorder episode, which are based on retrospective reporting from the child or parent, in some cases years after the episode ended which could affect recall. We grouped anxiety disorders together; however, anxiety disorders comprise a range of specific symptoms and impairment. The group-based trajectory models cluster children with similar patterns of anxiety disorders, as a result, a small subset of children with shorter duration anxiety disorders are allocated into the no/low anxiety trajectory. The three-step approach with most-likely class membership may result in observed attenuated effects between parent/grandparent MDD and trajectory group.(Bakk Z, Tekle FB, & Vermunt JK, 2013; Heron JE, Croudace TJ, Barker E, & Tilling KM, 2015) We observed negligible changes under probabilistic group assignment.(Sweeten G, 2014) Treatment of anxiety disorders, which we do not evaluate, may influence an individual’s anxiety disorder trajectory.

Conclusions

Anxiety disorders are prevalent, typically onset during children, and often precede other psychiatric conditions. Describing the heterogeneous course of childhood-onset anxiety disorders allows exploration and understanding past binary measures, taking a life course perspective. Clinically relevant differences between children with no/low anxiety, non-persistent anxiety, and persistent anxiety were present in both generations and may assist in identifying opportunities to intervene. Further, history of grandparent and parent moderate/severe MDD may help clinicians identify children at greater risk for persistent anxiety and adverse outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (Bethesda, MD) under Award Numbers T32MH013043, R01MH036197, and R01MH114967. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funding source had no role in the design of the study; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest statement. In the past 3 years, Dr. Weissman received funding from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Sackler Foundation, and the Templeton Foundation and has received royalties for the publication of books on interpersonal psychotherapy from Perseus Press and Oxford University Press, and on other topics from the American Psychiatric Association Press and royalties on the social adjustment scale from Multihealth Systems. Dr. Bushnell received support from the National Institute of Mental Health under Award Number T32MH013043. Drs. Gameroff, Talati, and Wickramaratne report no potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement. The data is not released publicly; for information on access to the data, please go to the website: highriskdepression.org

REFERENCES

- Ahlen J, & Ghaderi A (2019). Dimension-specific symptom patterns in trajectories of broad anxiety: A longitudinal prospective study in school-aged children. Dev Psychopathol, 1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418001384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan NP, Capron DW, Lejuez CW, Reynolds EK, MacPherson L, & Schmidt NB (2014). Developmental trajectories of anxiety symptoms in early adolescence: the influence of anxiety sensitivity. J Abnorm Child Psychol, 42(4), 589–600. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9806-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselmann E, & Beesdo-Baum K (2015). Predictors of the course of anxiety disorders in adolescents and young adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 17(2), 7. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0543-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakk Z, Tekle FB, & Vermunt JK. (2013). Estimating the Association Between Latent Class Membership and External Variables Using Bias-Adjusted Three-Step Approaches. Sociological Methodology, 43(1), 272–311. [Google Scholar]

- Batelaan NM, Rhebergen D, Spinhoven P, van Balkom AJ, & Penninx BW (2014). Two-year course trajectories of anxiety disorders: do DSM classifications matter? J Clin Psychiatry, 75(9), 985–993. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia M, Touchette E, Garon-Carrier G, Dionne G, Cote SM, Vitaro F,… Boivin M (2016). Distinct trajectories of separation anxiety in the preschool years: persistence at school entry and early-life associated factors. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 57(1), 39–46. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo-Baum K, & Knappe S (2012). Developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am, 21(3), 457–478. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts KS, Baker P, Alati R, McIntosh JE, Macdonald JA, Letcher P, & Olsson CA (2016). The natural history of internalizing behaviours from adolescence to emerging adulthood: findings from the Australian Temperament Project. Psychol Med, 46(13), 2815–2827. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716001495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittner A, Egger HL, Erkanli A, Jane Costello E, Foley DL, & Angold A (2007). What do childhood anxiety disorders predict? J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 48(12), 1174–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01812.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Angold A, Shanahan L, & Costello EJ (2014). Longitudinal patterns of anxiety from childhood to adulthood: the Great Smoky Mountains Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 53(1), 21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, & Angold A (2009). Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 66(7), 764–772. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote SM, Ahun MN, Herba CM, Brendgen M, Geoffroy MC, Orri M,… Tremblay RE (2018). Why Is Maternal Depression Related to Adolescent Internalizing Problems? A 15-Year Population-Based Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 57(12), 916–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote SM, Boivin M, Liu X, Nagin DS, Zoccolillo M, & Tremblay RE (2009). Depression and anxiety symptoms: onset, developmental course and risk factors during early childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 50(10), 1201–1208. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02099.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti E, Klimstra T, Keijsers L, Hale WW 3rd, & Meeus W (2009). Anxiety trajectories and identity development in adolescence: a five-wave longitudinal study. J Youth Adolesc, 38(6), 839–849. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9302-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne S, Larose S, Vitaro F, & Tremblay RE (2010). Trajectories of anxiety in a population sample of children: clarifying the role of children’s behavioral characteristics and maternal parenting. Dev Psychopathol, 22(2), 361–373. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, & Cohen J (1976). The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 33(6), 766–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770060086012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Lewinsohn PM, Lim JX, Ho MR, & Rohde P (2018). Incidence, recurrence and comorbidity of anxiety disorders in four major developmental stages. J Affect Disord, 228, 248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Lewinsohn PM, Olaya B, & Seeley JR (2014). Anxiety disorders in adolescents and psychosocial outcomes at age 30. J Affect Disord, 163, 125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.12.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Shaw DS, & Silk JS (2008). Developmental trajectories of anxiety symptoms among boys across early and middle childhood. J Abnorm Psychol, 117(1), 32–47. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster CE, Webster MC, Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Rush AJ,… King CA (2008). Course and Severity of Maternal Depression: Associations with Family Functioning and Child Adjustment. J Youth Adolesc, 37(8), 906–916. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9216-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg GS, Becker-Haimes EM, Keeton C, Kendall PC, Iyengar S, Sakolsky D,… Piacentini J (2018). Results From the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Extended Long-Term Study (CAMELS): Primary Anxiety Outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 57(7), 471–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Burden of Disease Pediatrics, Kyu C, Pinho HH, Wagner C, Brown JA, Bertozzi-Villa JC, A.,… Vos T. (2016). Global and National Burden of Diseases and Injuries Among Children and Adolescents Between 1990 and 2013: Findings From the Global Burden of Disease 2013 Study. JAMA Pediatr, 170(3), 267–287. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron JE, Croudace TJ, Barker E, & Tilling KM. (2015). A comparison of approaches for assessing covariate effects in latent class analysis. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 6(4), 420–434. [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, & Nagin DS (2007). Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and an SAS procedure for estimating them. Sociological Methods & Research, 35(4), 542–571. doi: 10.1177/0049124106292364 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, Nagin DS, & Roeder K (2001). A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociological Methods & Research, 29(3), 374–393. doi:Doi 10.1177/0049124101029003005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P,… Ryan N (1997). Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Sholomskas D, Thompson WD, Belanger A, & Weissman MM (1982). Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: a methodological study. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 39(8), 879–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legerstee JS, Verhulst FC, Robbers SC, Ormel J, Oldehinkel AJ, & van Oort FV (2013). Gender-Specific Developmental Trajectories of Anxiety during Adolescence: Determinants and Outcomes. The TRAILS Study. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 22(1), 26–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb R, Isensee B, Hofler M, Pfister H, & Wittchen HU (2002). Parental major depression and the risk of depression and other mental disorders in offspring: a prospective-longitudinal community study. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 59(4), 365–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannuzza S, Fyer AJ, Klein DF, & Endicott J (1986). Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia--Lifetime Version modified for the study of anxiety disorders (SADS-LA): rationale and conceptual development. J Psychiatr Res, 20(4), 317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L,… Swendsen J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity study-adolescent supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minjung K, Jeroen V, Zsuzsa B, Thomas J, & Lee VHM (2016). Modeling predictors of latent classes in regression mixture models. Struct Equ Modeling, 23(4), 601–614. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2016.1158655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, & Odgers CL (2010). Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol, 6, 109–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, Milan S, & Vannucci A (2017). Gender Differences in Anxiety Trajectories from Middle to Late Adolescence. J Youth Adolesc, 46(4), 826–839. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0619-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, & Seeley JR (2010). Latent trajectory classes of depressive and anxiety disorders from adolescence to adulthood: descriptions of classes and associations with risk factors. Compr Psychiatry, 51(3), 224–235. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Stepp SD, Keenan K, Loeber R, & Hipwell A (2014). Trajectories of depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescent girls: a comparison of parallel trajectory approaches. J Pers Assess, 96(3), 316–326. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2013.866570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J, Chambers W, Tabrizi MA, & Johnson R (1982). Retrospective assessment of prepubertal major depression with the Kiddie-SADS-e. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry, 21(4), 392–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeten G (2014). Group-Based Trajectory Models In Bruinsma G & Weisburd D (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Twisk J, & Hoekstra T (2012). Classifying developmental trajectories over time should be done with great caution: a comparison between methods. J Clin Epidemiol, 65(10), 1078–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner V, Weissman MM, Mufson L, & Wickramaratne PJ (1999). Grandparents, parents, and grandchildren at high risk for depression: a three-generation study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 38(3), 289–296. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199903000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner V, Wickramaratne P, & Weissman MM (2008). The role of fear and anxiety in the familial risk for major depression: a three-generation study. Psychol Med, 38(11), 1543–1556. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Berry OO, Warner V, Gameroff MJ, Skipper J, Talati A,… Wickramaratne P (2016). A 30-Year Study of 3 Generations at High Risk and Low Risk for Depression. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(9), 970–977. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Gammon GD, John K, Merikangas KR, Warner V, Prusoff BA, & Sholomskas D (1987). Children of depressed parents. Increased psychopathology and early onset of major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 44(10), 847–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Leckman JF, Merikangas KR, Gammon GD, & Prusoff BA (1984). Depression and anxiety disorders in parents and children. Results from the Yale family study. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 41(9), 845–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wolk S, Wickramaratne P, Goldstein RB, Adams P, Greenwald S,… Steinberg D (1999). Children with prepubertal-onset major depressive disorder and anxiety grown up. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 56(9), 794–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Lieb R, Pfister H, & Schuster P (2000). The waxing and waning of mental disorders: evaluating the stability of syndromes of mental disorders in the population. Compr Psychiatry, 41(2 Suppl 1), 122–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward LJ, & Fergusson DM (2001). Life course outcomes of young people with anxiety disorders in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 40(9), 1086–1093. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200109000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerwas S, Von Holle A, Watson H, Gottfredson N, & Bulik CM (2014). Childhood anxiety trajectories and adolescent disordered eating: findings from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development. Int J Eat Disord, 47(7), 784–792. doi: 10.1002/eat.22318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.