Abstract

Objective:

Systematic approach to myelolipoma remains poorly defined. We aimed to describe clinical course of myelolipoma and to identify predictors of tumor growth and need for surgery.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective study of consecutive patients with myelolipoma.

Results:

A total of 321 myelolipomas (median size, 2.3 cm) were diagnosed in 305 patients at median age of 63 years (range, 25-87). Median follow-up was 54 months. Most myelolipomas were incidentally detected (86%), whereas 9% were discovered during cancer staging, and 5% during workup of mass effect symptoms. Thirty seven (12%) patients underwent adrenalectomy. Compared to myelolipomas <6 cm, tumors ≥6 cm were more likely to be right-sided (59% vs 41%, P=0.02), bilateral (21% vs 3%, P<.0001), cause mass effect symptoms (32% vs 0%, P<.0001), have hemorrhagic changes (14% vs 1%, P<.0001), and undergo adrenalectomy (52% vs 5%, P<.0001). Among patients with ≥6 months of imaging follow-up, median size change was 0 mm (−10, 115) and median growth rate was 0 mm/year (−6, 14). Compared to <1 cm growth, ≥1 cm growth correlated with larger initial size (3.6 vs 2.3 cm, P=0.02), hemorrhagic changes (12% vs 2%, P=0.007), and adrenalectomy (35% vs 8%, P<.0001).

Conclusions:

Most myelolipomas are incidentally discovered on cross-sectional imaging. Myelolipomas ≥6 are more likely to cause mass effect symptoms, have hemorrhagic changes, and undergo resection. Tumor growth ≥1 cm is associated with larger myelolipoma and hemorrhagic changes. Adrenalectomy should be considered in symptomatic patients with large tumors and when there is evidence of hemorrhage or tumor growth.

Keywords: adrenal mass, adrenal tumor, adrenal incidentaloma, adrenal adenoma, adrenal function, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, adrenalectomy, lipomatous adrenal tumors, adrenal cortical adenoma, adrenal myelolipoma, adrenal cortex hormones

Summary:

Most myelolipomas are incidental, small, asymptomatic, and slow-growing. Tumor growth ≥1 cm is associated with larger myelolipoma and presence of radiographic hemorrhagic changes. Surgery should be considered in symptomatic patients with large tumors, evidence of hemorrhage, or tumor growth.

Introduction

Adrenal myelolipoma is a benign adrenocortical tumor composed of adipose tissue and bone marrow elements1,2. It is the second most common tumor of the adrenal gland reported in one out of 500-1250 autopsy cases3. Myelolipoma is commonly diagnosed in the fifth and sixth decade of life with no obvious sex predilection4–6. The pathogenesis of myelolipoma is unclear, although it is hypothesized to develop from mesenchymal cell metaplasia or as a result overstimulation by increased corticotropin (ACTH) secretion7,8. Increasing incidence of myelolipoma is largely attributed to widespread use of abdominal imaging, accounting for prevalence of 6-16% of adrenal incidentalomas9–11. Although large myelolipomas can lead to mass effect symptoms, most myelolipomas are asymptomatic and are detected incidentally during evaluation for unrelated symptoms or cancer staging. Histopathologic hemorrhagic changes are described in up to 19% of cases, whereas spontaneous tumor rupture is reported in 4.5% of myelolipomas, more commonly in large myelolipomas measuring 10-12 cm13. Coexisting adrenocortical tumors and congenital adrenal hyperplasia are described in 5.7% and 10% of myelolipoma cases, respectively12,13.

Despite high prevalence of adrenal myelolipoma, most data on longitudinal follow-up of these tumors are limited to surgical case series, with inadvertent bias of describing symptomatic and surgically treated cases. Moreover, clinical guidelines on management of adrenal tumors lack evidence-based recommendations on evaluation and management of myelolipoma14,15. Therefore, we aimed to provide a perspective on the natural history, management and outcomes of consecutive patients with myelolipoma, and to identify predictors of tumor growth and surgical resection.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

We performed a retrospective longitudinal follow-up study of consecutive patients with adrenal myelolipoma evaluated at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN, USA) between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2016. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. The Mayo Clinic Adrenal Tumor database was reviewed to identify all patients with myelolipoma. The diagnosis was based on computerized tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or post-operative histopathology of the tumor. Definition of myelolipoma by CT was based on the characteristic appearance of a well-circumscribed nonhomogeneous macroscopic fat-containing adrenal mass with low attenuation on unenhanced imaging and no enhancement with contrast medium. Definition of myelolipoma by MRI was based on a high signal intensity on T1-weighted images due to macroscopic fat content, confirmed by demonstrating a loss of signal intensity within the fatty component on the out-of-phase images. All electronic medical records were reviewed for confirmation of diagnosis, radiologic and biochemical evaluation, management and follow-up.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to provide a summary of the data. Categorical data were reported as absolute and relative frequencies (percentages). Continuous data were presented as median (minimum to maximum range). To compare medians between two independent groups, we used the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. Logistic regression models were used to estimate association of factors of tumor size, tumor growth, and need for surgical resection. All tests were two-sided, and P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using JMP version 13 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Clinical characteristics

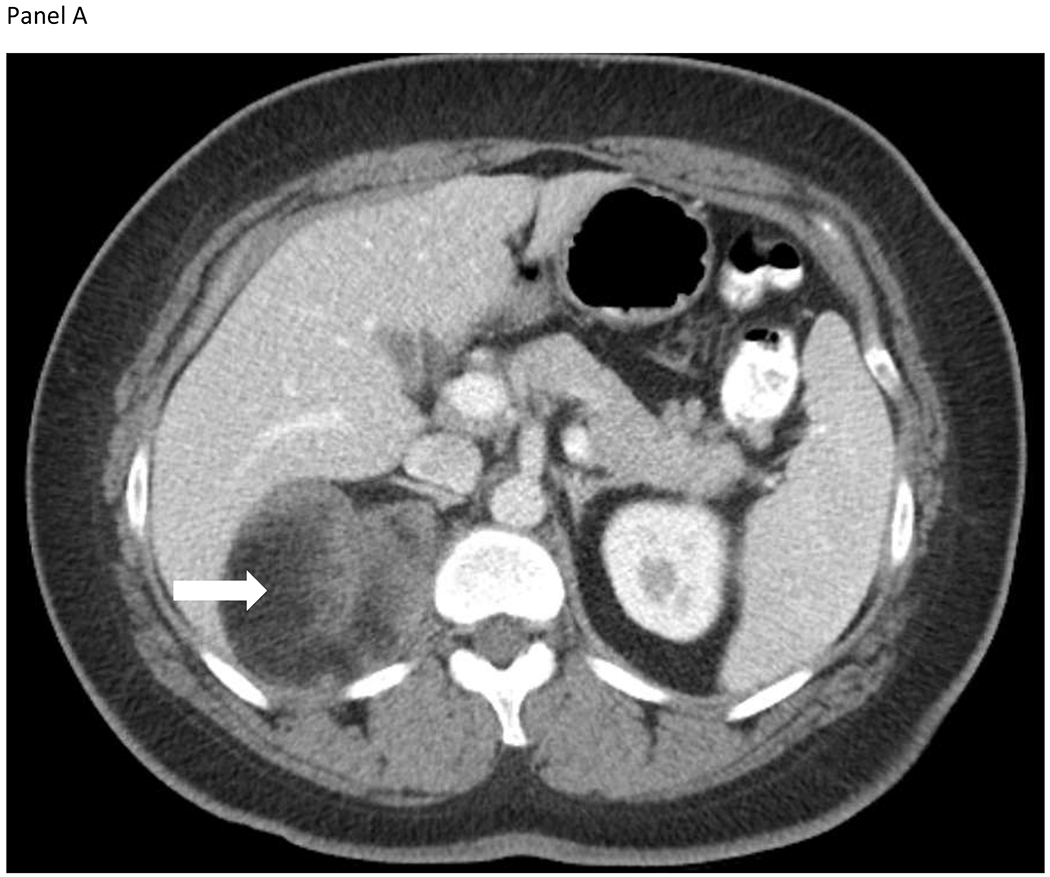

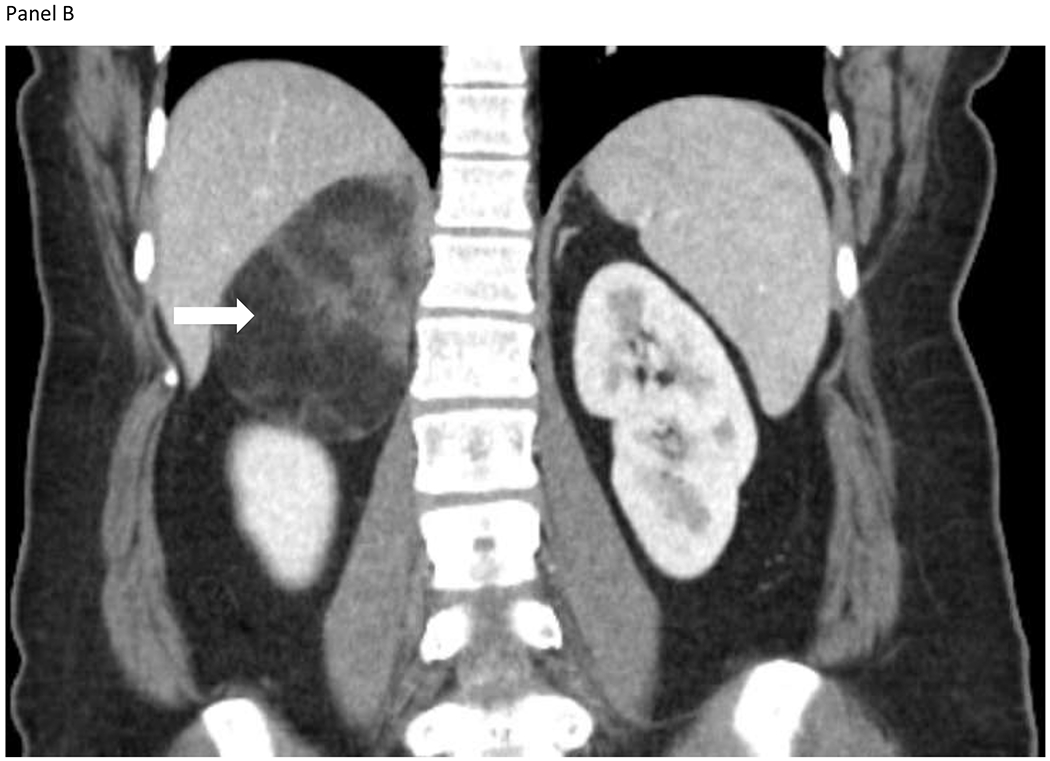

Of 4957 consecutive patients with adrenal tumors, 305 (6.2%) were diagnosed with myelolipoma based on radiographic and/or histopathological data (when available). Median age at diagnosis was 63 years (range, 25-x87). Overall, 305 patients (n=168, 55% men) presented with 321 myelolipomas: 141 (43.9%) right-sided and 180 (56.1%) left-sided. A total of 289 (94.8%) patients had unilateral and 16 (5.3%) had bilateral myelolipomas (Table 1). At initial evaluation, median tumor size was 2.3 cm (range, 0.5-18.0) and median unenhanced CT attenuation was −37.8 Hounsfield units (HU) (range, −110, 41) (Figure, Panels A and B). Of 2 myelolipomas with unenhanced CT attenuation >10 HU, 1 had acute hemorrhage (26 HU) and 1 had small central calcifications (41 HU). In the latter case, magnetic resonance imaging showed a loss of signal on the out-of-phase sequence within the peripheral aspect of the mass consistent with macroscopic fat.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Total (N=305) | <6 cm (n=261) | ≥6 cm (n=44) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex – no. (%) | 168 (55) | 140 (54) | 28 (64) | 0.22 |

| Age – yr (range) | 63 (25-87) | 64 (27-87) | 56.5 (25-84) | 0.09 |

| Mode of discovery – no. (%) | ||||

| Incidental | 27 (9) | 24 (91) | 3 (7) | <.0001 |

| Cancer staging | 27 (9) | 24 (91) | 3 (7) | |

| Mass effect symptoms | 14 (5) | 0 | 14 (32) | |

| Location – no. (%) | ||||

| Right | 141 (44) | 110 (41) | 31 (59) | 0.02 |

| Left | 180 (56) | 158 (59) | 22 (42) | |

| Unilateral | 289 (95) | 254 (97) | 35 (80) | <.0001 |

| Bilateral | 16 (5) | 7/261 (3) | 9 (20) | |

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia – no. (%) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (2.3) | 0.15 |

| Hemorrhage – no. (%) | 9 (3) | 3 (1) | 6 (14) | <.0001 |

| Initial size (range) – cm | 2.3 (0.5-18.0) | 2.0 (0.5-5.8) | 8.5 (6.0-18.0) | <.0001 |

| Final size (range) – cm | 2.6 (0.5-19.3) | 2.5 (0.5-17.0) | 7.9 (6.0-19.3) | <.0001 |

| Hormonal workup – no. (%) | 126 (41) | 94/261 (36) | 32/44 (73) | <.0001 |

| Autonomous cortisol secretion | 3/92 (3) | 3/66 (5) | 0/26 (0) | 0.27 |

| Primary aldosteronism | 9/74 (12) | 8/58 (14) | 1/16 (6) | 0.41 |

| Pheochromocytoma | 0/96 (0) | 0/71 (0) | 0/25 (0) | -- |

| Adrenalectomy – no. (%) | 37 (12) | 14 (5) | 23 (52) | <.0001 |

| Laparoscopic | 21 (57) | 11 (79) | 10 (44) | 0.04 |

| Open | 15 (40) | 3 (21) | 12 (52) | 0.07 |

| Laparoscopic → open | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | x1 (4) | -- |

| Indication for surgery – no. (%) | ||||

| Large tumor size/tumor growth | 12 (32) | 5 (36) | 7 (31) | |

| Diagnostic surgery | 10 (27) | 4 (29) | 6 (26) | |

| Mass effect symptoms | 5 (14) | 1 (7) | 4 (17) | |

| Concomitant ipsilateral tumor w/ hormonal excessa | 4 (11) | 3 (21) | 1 (4) | |

| Acute hemorrhage | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 3 (13) | |

| Concomitant resection during non-adrenal surgeryb | 3 (8) | 1 (7) | 2 (9) | |

Two patients had autonomous cortisol secretion due to adrenal adenoma and 2 patients had primary aldosteronism due to adrenal adenoma.

One patient underwent bilateral adrenalectomy for definitive management of persistent Cushing disease after unsuccessful pituitary resection and 2 patients underwent adrenalectomy during resection of ipsilateral renal carcinoma.

Figure 1.

A 33-year-old woman presented with intermittent right upper quadrant pain. She also reported constipation, early satiety, and nausea. Computed tomography identified a 6.4 x 7.1 x 9.2-cm heterogeneous lesion containing macroscopic fat, arising from the medial limb of the right adrenal gland shown on the axial (Panel A) and coronal images (Panel B). The lesion contained internal diffusely distributed soft tissue components and perceived “claw sign”, consistent with a large adrenal myelolipoma. Biochemical workup was unremarkable. Symptoms subsided and the patient opted for observation.

Most myelolipomas were discovered incidentally (n=264, 86%), whereas some were found on cross-sectional imaging performed for cancer staging (n=27, 9%), or during workup of mass effect symptoms (n=14, 5%), including back/flank pain (n=12), positional dyspnea (n=1), and provoked pulmonary embolism due to compression of the inferior vena cava (n=1). Of 12 (4%) patients who were evaluated for congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), 2 (0.7%) were diagnosed with CAH and 10 had either testing for CAH (n=9) or thorough history for CAH (n=1). A total of 19 (6.2%) had concomitant adrenocortical adenoma (contralateral = 12, ipsilateral = 7).

Five (1.7%) patients underwent diagnostic biopsy of the adrenal myelolipoma. There were no reported biopsy-related complications.

Patients were followed for a median of 54 months (range, 0.03-267). Adrenalectomy was performed in 37 (12%) patients with no reported surgical complications. Of 163 (53%) patients with ≥6 months of follow-up imaging performed at a median of 55 months (6-239), overall tumor growth/year was 0 mm (−6, 14). Overall duration of follow-up of patients with ≥6 months of follow-up imaging was 87 months (6-240). At study conclusion, 67 (22%) patients died of unrelated to adrenal mass reason.

Myelolipoma <6 cm vs ≥6 cm

A total of 44 (14.4%) patients had large (≥6 cm) myelolipomas, whereas 11 (3.6%) patients had myelolipomas ≥10 cm. When compared to <6 cm tumors, myelolipomas ≥6 cm were more likely to cause mass effects symptoms (31.8% vs 0%, P<.0001), be bilateral (9/44, 20.5% vs 7/261, 2.7%, P <.0001), have radiographic hemorrhagic changes (13.6% vs 1.1%, P<.0001), and more commonly underwent adrenalectomy (52.3% vs 5.4%, P<.0001). There was no difference in sex, age at diagnosis, or evidence of hormonal hyperfunction between patients with <6 cm vs ≥6 cm myelolipomas (Table 1). Three out of 44 (6.8%) patients with ≥6 cm myelolipoma underwent surgery due to acute hemorrhage, whereas none of myelolipomas <6 cm required surgery for this indication.

There were 3 patients with large (≥6 cm) symptomatic myelolipomas who were followed conservatively. One patient had bilateral myelolipomas (a 10.9-cm right myelolipoma with radiographic hemorrhagic changes and a 2.7-cm left myelolipoma). The large right myelolipoma showed mild decreased in size on follow-up imaging (from 10.9 cm to 10 cm over 22 months). The decrease in size was attributed to involution of the hemorrhage within the mass. The 2.7-cm left adrenal myelolipoma remained stable in size and appearance. The second patient followed conservatively demonstrated stable size of the 9-cm asymptomatic left adrenal myelolipoma on imaging 2 years after initial diagnosis. The third patient with a 6-cm myelolipoma and abdominal pain was simultaneously diagnosed with prostate cancer. Mass effect symptoms resolved without intervention.

Myelolipoma with radiographic hemorrhagic changes

Radiographic hemorrhagic changes within the myelolipoma were noted in 9 (3%) patients (3 women and 6 men), most noted in large tumors (median tumor size of 7.0 cm; range, 1.8-18.0). Five patients presented with mass effect symptoms (median size, 9.0 cm; range, 4.5-18.0 cm) and 4 were found to have myelolipomas incidentally (median size, 4.6 cm; range, 1.8-7.0). Hemorrhagic changes were more common in tumors ≥6 cm as opposed to <6 cm (n=6 [13.6%] vs n=3 [1.1%], P<.0001). Only 1 patient with hemorrhagic myelolipoma was on anticoagulation, while hemorrhage was thought to be unprovoked in 8 patients. Among 5 patients treated with adrenalectomy, indications for surgery included: acute hemorrhage (n=3), diagnostic surgery (n=1), and mass effect symptoms (n=1). Two patients underwent laparoscopic resection, 2 had open surgery and 1 had laparoscopic surgery that was converted to open. None had congenital adrenal hyperplasia or concomitant adrenal adenoma.

Hormonal evaluation

Of 126 (41.3%) patients evaluated for adrenal hormone excess, the majority (n=114, 90.5%) demonstrated no evidence of autonomous hormonal hyperfunction. Among those with available data, 96 patients underwent evaluation for pheochromocytoma, and no cases of pheochromocytoma were found. Of 92 patients with biochemical evaluation for autonomous cortisol secretion (excluding one patient with persistent Cushing disease due to ACTH-producing pituitary adenoma), 3 (3.3%) were noted to have autonomous cortisol secretion attributed to concomitant contralateral (n=2) or ipsilateral adrenocortical adenoma (n=1) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Characteristics of patients with myelolipoma and autonomous hormonal secretion.

| Pt, Age/sex | Imaging | Discovery | Reason for surgery | Surgery | Pathology | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt1, 65/M | Left 0.8-cm myelolipoma Right ?cm adrenal adenoma | Incidental | Autonomous cortisol secretion | Right adrenalectomy | Adrenocortical adenoma | Contralateral adrenalectomy for adrenal adenoma and autonomous cortisol secretion |

| Pt2, 71/M | Right 4.0 cm myelolipoma and right 2.8-cm adrenal adenoma | Incidental | Autonomous cortisol secretion | Right adrenalectomy | Myelolipoma and adrenocortical adenoma | Ipsilateral adrenalectomy for adrenal adenoma and autonomous cortisol secretion |

| Pt3, 52/M | Left 1.6-cm myelolipoma and right 4.6-cm adrenal adenoma | Incidental | Autonomous cortisol secretion | Right adrenalectomy | Right adrenocortical adenoma | Contralateral adrenalectomy for adrenal adenoma and autonomous cortisol secretion |

| Pt4, 51/F | Left 4.0-cm myelolipoma | Incidental | FNA: myelolipoma Primary aldosteronism due to IHA Lost to follow-up | |||

| Pt5, 67/M | Left 1.4-cm myelolipoma | Incidental | Primary aldosteronism | Left adrenalectomy | Not available | Lateralization confirmed by AVS Ipsilateral adrenalectomy for adrenal adenoma and primary aldosteronism |

| Pt6, 66/M | Left 3.5-cm myelolipoma | Incidental | Diagnostic surgery | Left adrenalectomy | Myelolipoma | Primary aldosteronism due to IHA treated with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist |

| Pt7, 82/M | Right 7.6-cm myelolipoma | Incidental | Primary aldosteronism due to IHA treated with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist | |||

| Pt8, 65/F | Right 4.0-cm myelolipoma | Incidental | Primary aldosteronism due to ipsilateral adrenal adenoma Poor surgical candidate | |||

| Pt9, 77/M | Right 1.0-cm myelolipoma and left 1.2-cm myelolipoma | Incidental | Primary aldosteronism due to contralateral adenoma treated with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist | |||

| Pt10, 56/M | Left 0.8-cm myelolipoma | Incidental | Primary aldosteronism | Left adrenalectomy | Not available | Lateralization confirmed by AVS Ipsilateral adrenalectomy for adrenal adenoma and primary aldosteronism |

| Pt11, 62/M | Left 1.0-cm myelolipoma | Incidental | Primary aldosteronism | Right adrenalectomy | Adrenocortical adenoma | Lateralization confirmed by AVS Contralateral adrenalectomy for primary aldosteronism and adrenal adenoma |

| Pt12, 71/M | Right 2.0-cm myelolipoma | Incidental | Primary aldosteronism | Left adrenalectomy | Adrenocortical adenoma | Contralateral adrenalectomy for primary aldosteronism and adrenal adenoma |

Abbreviations used: AVS, adrenal vein sampling; FNA, fine-needle aspiration; IHA, bilateral idiopathic hyperaldosteronism

Of 74 patients that underwent biochemical evaluation for aldosterone excess, primary aldosteronism was noted in 9 (12.2%) patients: due to concomitant ipsilateral (n=3) or contralateral adrenocortical adenoma (n=3), or bilateral idiopathic adrenal hyperplasia (n=3).

Tumor growth

A total of 163 (53.4%) patients had ≥6 months of follow-up imaging from initial diagnosis and were included in the analysis of tumor growth, with median duration of overall clinical follow-up of 87 months (range, 6–240 months). Ten (6.1%) patients had bilateral myelolipomas, whereas 153 (93.8%) had unilateral tumors (74 right and 99 left) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with ≥6 months of follow-up imaging.

| Characteristic | Total (n=163) | <1.0 cm growth (n=135) | ≥1.0 cm growth (n=26) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex – no. (%) | 97 (60) | 79 (59) | 16 (62) | 0.77 |

| Age – yr (range) | 62 (27-86) | 63 (28-86) | 57 (27-86) | 0.09 |

| Mode of discovery – no. (%) | ||||

| Incidental | 140 (86) | 116 (86) | 23 (89) | 0.67 |

| Cancer staging | 18 (11) | 15 (11) | 3 (11) | |

| Mass effect symptoms | 5 (3) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Hemorrhage – no. (%) | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (12) | 0.007 |

| Initial size (range) – cm | 2.4 (0.5-18.0) | 2.2 (0.5-13.3) | 3.6 (0.8-18.0) | 0.01 |

| Adrenalectomy – no. (%) | 14 (9) | 5 (4) | 9 (35) | <.0001 |

| Final size (range) – cm | 2.6 (0.5-19.3) | 2.3 (0.5-14.0) | 5.9 (2.3-19.3) | <.0001 |

| Overall change in size (range) – mm | 0 (−10, 115) | 0 (−10, 95) | 20 (10-115) | <.0001 |

| Rate of growth (range) – mm/yr | 0 (−6, 14) | 0 (−5.6, 14) | 3.0 (1-11.0) | <.0001 |

Of these, 26 (16.0%) myelolipomas increased by ≥1.0 cm over the duration of follow-up. Myelolipomas with ≥1.0 cm growth were larger at initial diagnosis (3.6 cm vs 2.2 cm, P=0.01), more likely to have hemorrhagic changes (11.5% vs 0.7%, P=0.007), and more commonly treated surgically (34.6% vs 3.7%, P<.0001), compared to myelolipomas with <1 cm overall growth.

At last follow-up, overall tumor change ranged from −10 mm to 115 mm (median, 0 mm) with growth rate ranging from −6 mm/year to 14 mm/year (median, 0 mm/year).

Surgical resection

A total of 37 (12.1%) patients underwent adrenalectomy: 21 (56.8%) patients underwent laparoscopic adrenalectomy, 15 (40.5%) – open adrenalectomy, and 1 (2.7%) – a laparoscopic adrenalectomy that was converted to open resection (pathology showed an 8.9 cm myelolipoma with fat necrosis and organizing hemorrhage) (Table 4). Indications for surgery included: prevention of tumor growth due to large tumor size or tumor growth at follow-up (n=12), diagnostic surgery (n=10), mass effect symptoms (n=5), concomitant ipsilateral adrenal adenoma with hormonal excess (n=4), acute hemorrhage (n=3), and concomitant resection during surgery for another indication (n=3) (Table 1).

Table 4.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who underwent adrenalectomy vs observation.

| Characteristic | Surgical resection (n=37) | Observation (n=268) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex – no. (%) | 23 (62) | 145 (54) | 0.36 |

| Age – yr (range) | 55 (25–86) | 64 (27–87) | 0.02 |

| Mode of discovery – no. (%) | |||

| Incidental | 25 (68) | 239 (89) | <0.001 |

| Cancer staging | 1 (2) | 26 (10) | |

| Mass effect symptoms | 11 (30) | 3 (1) | |

| Initial size (range) – cm | 6.8 (0.8–18.0) | 2.2 (0.5–18.0) | <.0001 |

| Overall change in size (range) – cm | 1.3 (−0.2, 11.5) | 0 (−1.0, 3.9) | <.0001 |

| ≥1.0 cm growth, overall – no. (%) | 9/15 (60) | 17/155 (11) | <.0001 |

| Growth rate (range) – mm/year | 4.5 (−6, 14) | 0 (−5.6, 7.8) | <.0001 |

| Hemorrhage – no. (%) | 5 (14) | 4 (1) | <.0001 |

| Hormonal workup – no. (%) | |||

| Autonomous cortisol secretion | 1/20 (5) | 2/72 (3) | 0.62 |

| Primary aldosteronism | 3/14 (21) | 6/60 (10) | 0.24 |

| Pheochromocytoma | 0/24 (0) | 0/72 (0) | -- |

| Median follow-up (range) – mo | 54 (1-226) | 54.5 (0.01-267) | 0.79 |

Among 12 patients who underwent surgery for prevention of further tumor growth (due to large initial tumor size or tumor growth at follow-up), median initial tumor size was 8.0 cm (range, 1.5-15.0) and median rate of tumor growth was 5.6 mm/year (range, 2.8-14).

Discussion

In this longitudinal follow-up study, we characterized demographics, clinical presentation, and management of 305 consecutive patients with adrenal myelolipoma followed for a median of 4.5 years. We found that most myelolipomas were small (median tumor size of 2.3 cm), asymptomatic, and remained stable in size on follow-up imaging. Similar to our findings, another large retrospective study of 150 patients with myelolipoma discovered on imaging showed that mean tumor size was 2.1 cm and only 8% of myelolipomas measured ≥6 cm16. In contrast, a recent review of previously reported cases and case series (420 patients) summarized that myelolipomas are usually large tumors averaging at 10.2 cm, with 36% of tumors measuring greater than 10 cm13,17. The discrepancy between our findings and previously reported case series suggests a potential publication bias of primarily describing symptomatic myelolipoma cases.

Overall, myelolipomas remain stable in size or grow slowly. We found that median tumor size minimally increased from 2.3 cm to 2.6 cm and only 16% of myelolipomas grew by more than 1 cm over 4.5 years of median follow-up. In our longitudinal follow-up study, the annual growth rate ranged from −6 mm/year to 14 mm/year. Similarly, others reported >5 mm tumor growth in 16% of myelolipomas16. In a small study of 12 patients followed for 2.3 years, tumor size increased by a mean of 2 mm/year18. Similarly, tumor growth was shown in 11/69 (16%) patients with myelolipoma in another study, ranging from 0.8 mm/year to 7.1 mm/year (median, 1.6 mm/year) over 3.9 years of follow-up16. Although one study found that tumor growth was more likely in younger patients and longer duration of follow-up16, we found that significant tumor growth was associated with larger initial tumor size and presence of hemorrhagic changes, but not with age, sex or mode of discovery. Based on our findings, small myelolipomas without hemorrhagic changes do not require imaging follow-up, whereas large myelolipomas or those with hemorrhagic changes on initial imaging should undergo additional follow-up or undergo resection.

Most adrenal myelolipomas do not require surgical intervention or monitoring. In our cohort, 12% of patients underwent resection of myelolipoma. Surgical resection was more common in younger patients, in those with symptoms of mass effect, in patients with larger tumors, or tumors that had radiographic hemorrhagic changes or increased in size. In accordance with other studies, laparoscopic adrenalectomy appears safe and effective19–21. One study recommended surgical resection for all lipomatous tumors ≥3.5 cm, in addition to tumors leading to mass effect symptoms and those with uncertain diagnosis based imaging characteristics17. However, our findings support that conservative management is preferred for most patients with myelolipomas due to their benign and indolent nature. Surgery may be indicated for large symptomatic myelolipomas, those with diagnostic uncertainty, or those with significant tumor growth.

Spontaneous rupture and retroperitoneal hemorrhage of myelolipoma are exceedingly rare and more commonly described in large tumors measuring more than 6-7 cm12. While radiographic hemorrhagic changes were seen in 9 (3%) patients in the present study, acute hemorrhage/tumor rupture requiring surgical intervention was reported in only 3 (0.9%) patients, all with myelolipomas ≥6 cm. Another study of incidentally discovered myelolipomas identified no cases of myelolipoma with retroperitoneal hemorrhage16. In contrast, several studies reported up to 4.5% of cases with tumor rupture, most in large myelolipomas greater than 10 cm13,22,23. Higher prevalence of tumor rupture in previous reports raises a concern for publication bias.

Current guidelines for the management of adrenal incidentaloma do not propose hormonal evaluation for obvious myelolipoma14,15. Although adrenal myelolipomas do not contain any adrenal cortical or medullary components and are not hormonally active, coexisting hormone hypersecretion and adrenocortical adenomas are reported in 7.5% and 5.7% of myelolipoma cases, respectively13. Hormonal hyperfunction in patients with myelolipoma is likely due to adrenal collision tumors coexisting with myelolipomas or coexisting ipsilateral or contralateral adrenal cortical adenomas or hyperplasia12. In our study, hormonal hypersecretion due to co-existing adrenal adenoma or hyperplasia was observed in 9.5% of cases. There were no cases of pheochromocytoma or adrenocortical carcinoma in the present study. Therefore, hormonal workup should be considered in patients with suspected co-existing adrenal adenoma and those with overt features of hormone excess (such as primary aldosteronism and overt Cushing syndrome), rather than all patients with myelolipoma.

Our study has several limitations including its retrospective design, limited length of follow-up, differences in follow-up and management strategies of patients over time, and partial workup and management done outside of our institution. First, prevalence of myelolipoma may be misrepresented in our study as we only evaluated patients who underwent abdominal imaging and the true rate and longitudinal history in those individuals without imaging follow-up could not be ascertained. Thus, all point estimates are based on available data and the possibility of initial imaging detection bias cannot be excluded. Many adrenal myelolipomas were diagnosed based on imaging characteristics and did not undergo histopathological confirmation of the diagnosis. Therefore, some of the tumors could have been misdiagnosed as myelololipoma based on the presence of macroscopic fat. Yet, the majority of myelolipomas rely on radiographic characteristics and cannot be histopathologically confirmed in clinical practice. Of importance, only those patients that had >6 months of serial imaging were included in the longitudinal analysis, which could potentially represent a repeat imaging bias and reflect underlying clinical concern and/or other high risk features. Additionally, indications for surgery varied based on an individual circumstance; therefore, symptomatic and/or large myelolipomas with concerning radiographic characteristics such as hemorrhage were more likely to be removed, contributing to selection bias. Another important limitation of our study is limited evaluation for CAH, with only 4% of our cohort undergoing evaluation for co-existing CAH. In our opinion, screening for CAH should be considered in all patients with bilateral myelolipomas, cortical adenomas or hyperplasia even in the absence of overt clinical findings. Strengths of the study include a large sample size and consecutive cohort of patients, as well as availability of detailed medical records.

In conclusion, most myelolipomas are small, asymptomatic, remain stable in size over time, and do not require surgical intervention or follow-up. In contrast, myelolipomas ≥6 are more likely to cause mass effect symptoms and have radiographic hemorrhagic changes. Hormonal excess is rare and is attributed to concomitant adrenocortical adenomas or hyperplasia. Adverse events such as tumor rupture and acute retroperitoneal hemorrhage are exceedingly rare. Tumor growth is associated with larger myelolipomas and presence of radiographic hemorrhagic changes. Surgical resection should be considered in symptomatic patients with large tumors, evidence of hemorrhage, or tumor growth.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the James A. Ruppe Career Development Award in Endocrinology (IB) and the Catalyst Award for Advancing in Academics from Mayo Clinic (IB). This research was partly supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) USA under award K23DK121888 (to I.B). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Institutes of Health USA.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: IB reports advisory board participation with Corcept Therapeutics, CinCore and HRA Pharma outside the submitted work. OH reports research collaboration with Mayo Clinic and advisory board participation with Corcept Therapeutics and Pfizer outside the submitted work.

An abstract of this study was published at the Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society on March 28th, 2020.

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Lam AK-yJEp. Update on adrenal tumours in 2017 World Health Organization (WHO) of endocrine tumours. 2017;28(3):213–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khater N, Khauli RJAjou. Myelolipomas and other fatty tumours of the adrenals. 2011;9(4):259–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsson CA, Krane RJ, Klugo RC, Selikowitz SMJS. Adrenal myelolipoma. 1973;73(5):665–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decmann Á, Perge P, Tóth M, Igaz P. Adrenal myelolipoma: a comprehensive review. Endocrine. 2018;59(1):7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Low G, Dhliwayo H, Lomas DJCr. Adrenal neoplasms. 2012;67(10):988–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam K, Lo CJJocp. Adrenal lipomatous tumours: a 30 year clinicopathological experience at a single institution. 2001;54(9):707–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selye H, Stone HJTAjop. Hormonally Induced Transformation Of Adernal into Myeloid Tissue. 1950;26(2):211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sieber S, Gelfman N, Dandurand R, Braza FJCm. Ectopic ACTH and adrenal myelolipoma. 1989;53(1):7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song JH, Chaudhry FS, Mayo-Smith WWJAJoR. The incidental adrenal mass on CT: prevalence of adrenal disease in 1,049 consecutive adrenal masses in patients with no known malignancy. 2008;190(5):1163–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bin X, Qing Y, Linhui W, Li G, Yinghao S. Adrenal incidentalomas: experience from a retrospective study in a Chinese population. Paper presented at: Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantero F, Masini A, Opocher G, Giovagnetti M, Arnaldi GJH. Adrenal incidentaloma: an overview of hormonal data from the National Italian Study Group. 1997;47(4-6):284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shenoy VG, Thota A, Shankar R, Desai MGJIjouIjotUSoI. Adrenal myelolipoma: controversies in its management. 2015;31(2):94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Decmann Á, Perge P, Tóth M, Igaz PJE. Adrenal myelolipoma: a comprehensive review. 2018;59(1):7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fassnacht M, Arlt W, Bancos I, et al. Management of adrenal incidentalomas: European society of endocrinology clinical practice guideline in collaboration with the European network for the study of adrenal tumors. 2016;175(2):G1–G34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaidya A, Hamrahian A, Bancos I, Fleseriu M, Ghayee HKJEP. THE EVALUATION OF INCIDENTALLY DISCOVERED ADRENAL MASSES. 2019;25(2):178–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell MJ, Obasi M, Wu B, Corwin MT, Fananapazir GJE. The radiographically diagnosed adrenal myelolipoma: what do we really know? 2017;58(2):289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao J, Sun F, Jing X, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of primary adrenal lipomatous tumours in Chinese patients: A 31-year follow-up study. 2014;8(3-4):E132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han M, Burnett A, Fishman EK, Marshall FJTJou. The natural history and treatment of adrenal myelolipoma. 1997;157(4):1213–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamashita S, Ito K, Furushima K, et al. Laparoscopic versus open adrenalectomy for adrenal myelolipoma. 2014;3(2):34–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaudhary R, Deshmukh A, Singh K, Biswas RJBcr. Is size really a contraindication for laparoscopic resection of giant adrenal myelolipomas? 2016;2016:bcr2016215048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agrusa A, Romano G, Frazzetta G, et al. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy for large adrenal masses: single team experience. 2014;12:S72–S74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu H-P, Chang W-Y, Chien S- T, et al. Intra-abdominal bleeding with hemorrhagic shock: a case of adrenal myelolipoma and review of literature. 2017;17(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sebastia M, Perez-Molina M, Alvarez-Castells A, Quiroga S, Pallisa EJEr. CT evaluation of underlying cause in spontaneous subcapsular and perirenal hemorrhage. 1997;7(5):686–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]