Highlights

-

•

This review reveals barriers of cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive women.

-

•

The uptake of cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive women is very low.

-

•

We reported personal, social and structural barriers of cervical cancer screening.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, Screening, Barriers, Facilitators, Low‐ and middle‐income countries, Patient-reported

Abstract

Cervical cancer is among the most common causes of cancer-related deaths in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Despite the strong evidence regarding cervical cancer screening cost-effectiveness, its utilization remains low especially in high risk populations such as HIV-positive women. The aim of this review was to provide an overview on the patient-reported factors influencing cervical cancer screening uptake among HIV-positive women living in LMICs. We systematically searched EMBASE, PUBMED/MEDLINE and Web of Science databases to identify all quantitative and qualitative studies investigating the patient-reported barriers or facilitators to cervical cancer screening uptake among HIV-positive population from LMICs. A total of 32 studies met the inclusion criteria. A large number of barriers/facilitators were identified and then grouped into three categories of personal, social and structural variables. However, the most common influential factors include knowledge and attitude toward cervical cancer or its screening, embarrassment, fear of cervical cancer screening and test results, patient-healthcare provider relationship, social support, screening costs and time constraints. This review’s findings highlighted the need for multi-level participation of policy makers, health professionals, patients and their families in order to overcome the barriers to uptake of cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive women, who are of special concern in LMICs.

1. Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common neoplasm affecting women worldwide, with approximately 90% of cases occurring in developing countries (Ferlay et al., 2015). Cervical cancer is a leading contributor to the increased burden of diseases in less developed regions and it is acknowledged as the second most common cancer among women in developing areas (445 000 new cases each year) and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality in developing countries (above 230 000 deaths each year) (Ferlay et al., 2015, Catarino et al., 2015).

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infection is known to be a well-elucidated risk factor of cervical cancer primarily through accelerating the development of pre-cancerous lesions in the cervix (Bonnet et al., 2004). HIV is also associated with higher rates of high-risk Human Papillomavirus (HR-HPV) acquisition, diminished clearance of HPV, more extensive pre-malignant lesions, and increased risk of cervical cancer when compared to HIV-negative women (Clifford et al., 2016, Massad et al., 2001). Furthermore, women with HIV have a more than two-fold risk of cervical cancer-related mortality compared to those who are HIV negative (Dryden-Peterson et al., 2016).

Cervical cancer is the only gynecological cancer for which screening tools are available, providing the opportunity for early detection of its precursor lesions. Several screening tests have been implemented for cervical cancer. Based on World Health Organization (WHO) reports (World Health Organization, 2006), the Pap test (cytology) is the only screening tool that has been studied in large populations and that has been shown to has been shown to effectively lower the risk of cervical cancer and cancer-related mortality. Other alternative screening tests such as visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) or Lugol's iodine (VILI) are feasible options in resource-limited settings where cytology-based screening tools are not applicable; however, there is not enough comparable evidence on their effectiveness (World Health Organization, 2006).

Despite introducing guidelines on cervical cancer screening for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), cervical cancer screening practice is considerably low in LMICs. Studies of HIV-positive women across LMICs demonstrate relatively low utilization of cervical cancer screening services. In recent surveys carried out among HIV-positive women in Ethiopia (Solomon et al., 2019), Morocco (Belglaiaa et al., 2018), South Africa (Godfrey et al., 2019) and Laos (Sichanh et al., 2014) revealed a low cervical cancer screening uptake of 24.8%, 13%, 32.5% and 5.6%, which demonstrated a large gap with developed countries where uptake of cervical cancer screening among women with HIV is 78% to 85.7% in United States (Ogunwale et al., 2016, Tello et al., 2010) and 53% in United Kingdom (Shah et al., 2006). Therefore, the goal of WHO strategic planning in introducing the “comprehensive cervical cancer control” program is currently far from being achieved, since only small proportion of women have actually done cervical cancer screening in LMICs.

The lower rates of cervical cancer screening uptake have been previously attributed to numerous demographic and clinical characteristics of HIV patients (e.g., socio-demographics, clinical staging of HIV, CD4 cell count and duration on antiretroviral therapy) (Bailey et al., 2012, Ebu et al., 2015). However, up to this point, not enough attention has been paid to the personal, social, and structural factors, noted by patients themselves, that may influence their decision whether to undergo screening or not.

To our knowledge, no published systematic review has addressed the question of what are the women’s self-reported barriers/facilitators to cervical cancer screening in resource-limited settings in LMICs. The aim of this review was to assess the patient-reported personal, social, and structural factors influencing cervical cancer screening uptake among HIV-positive women, to notify future research, and to evaluate whether women living with HIV have different unmet needs.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Search strategy and study selection

To identify the relevant studies, two independent authors (KH and MK) electronically conducted the searches in EMBASE, MEDLINE/PUBMED and Web of Science through January 2020 based on PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). The subject and text words search were performed separately in all relevant databases and then combined with ‘OR’ and ‘AND’ operators. The search included the following key words: ‘HIV’, ‘human immunodeficiency virus’, ‘AIDS’, ‘acquired immune deficiency syndrome’, ‘cervical cancer screening’, ‘pap test’, ‘pap smear’, ‘‘visual inspection with acetic acid’, ‘‘visual inspection with Lugol's iodine’, ‘VIA’, ‘VILI’, ‘cervical cancer’, ‘cervical neoplasm’, ‘barriers’, ‘facilitators’, ‘utilization’, ‘uptake’, ‘perception’, ‘attitude’, ‘self-reported’, ‘patient-reported’. The reference lists of relevant studies were also reviewed in order to detect further studies that were not captured in the primary search.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility criteria included original quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods (both quantitative and qualitative) research studies (i.e., not review articles, meta-analyses, conference papers, commentaries, or clinical trials) that (Ferlay et al., 2015) were written in English, (Catarino et al., 2015) have to be conducted in LMICs, defined as countries with a low- or middle-income status according to the World Bank’s classification, (Bonnet et al., 2004) must have assessed and reported patient-reported factors associated with uptake of cervical cancer screening in HIV-positive women in the quantitative literature or included factors women described as influencing their cervical cancer screening experience in the qualitative literature. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (Ferlay et al., 2015) not available in full text, (Catarino et al., 2015) those that did not specifically address barriers/facilitators to uptake of cervical cancer screening, (Bonnet et al., 2004) those did not clarify whether mentioned barriers/facilitators are reported by patients themselves or not (e.g., data regarding cervical cancer screening may extracted from medical charts or data registrations). It is important to note that during the reporting the results of included studies consisted of both HIV-positive and HIV-negative women, only data on HIV-positive subgroup was included and reported in the current review.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction and study quality assessment were performed independently by two researchers (HV and MK). In the case of disagreement among the 2 reviewers, it would be resolved by discussion with third author (NA). Regarding the study quality assessment, we used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), a tool designed for the quality appraisal of qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies (Pace et al., 2012). No study was excluded due to a low-quality assessment score.

We used summary tables to extract study characteristics of selected articles (i.e., authors, year and setting of the study, sample size, study design, age and screening status of participants, and main outcomes) along with quality assessment results. After reviewing and identifying several patient-reported factors associated with uptake of cervical cancer screening across included studies, these factors were grouped into three categories including personal, social, and structural barriers/facilitators based on “women’s autonomy in healthcare decision-making” (Sherwin, 1998), in order to organize a comprehensive overview of cervical cancer screening challenges among HIV-positive women living in LMICs. Briefly, personal factors include, but not limited to, knowledge and attitude, perceived susceptibility, embarrassment, fear of the cervical cancer screening procedure and test results, and experiencing cervical cancer-related symptoms. Social factors include the effectiveness of the patient–HCP relationship, stigma, information sources and social support from friends and family members. Structural factors include the screening costs, healthcare facility accessibility, time issues and resources/infrastructures.

3. Results

3.1. Search results and study characteristics

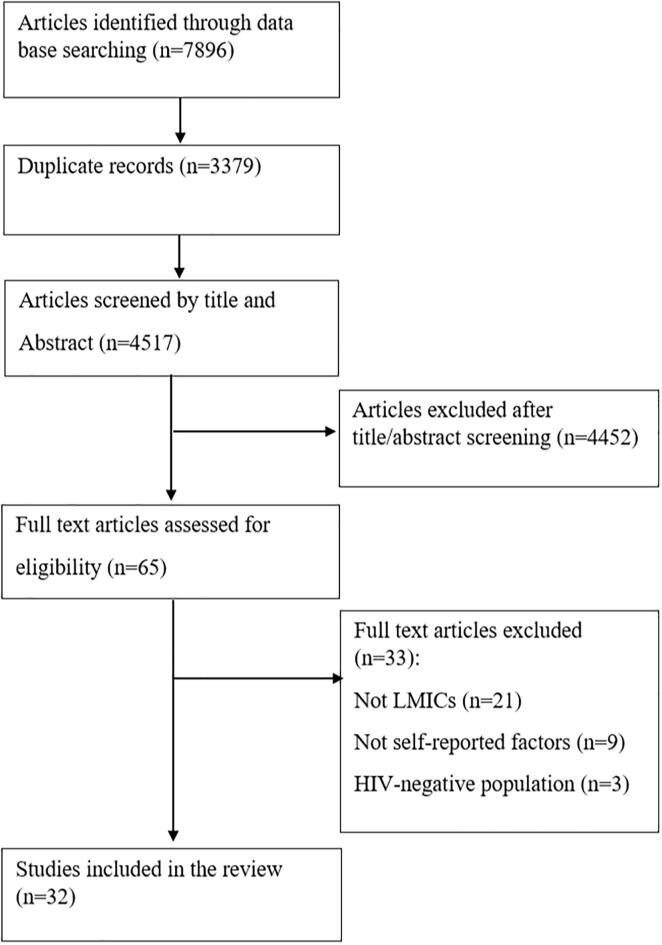

A total of 7896 articles were retrieved from the electronic databases search. After screening records, 32 articles were found to be eligible for inclusion in this review. The details of step by step study identification and selection are shown in Fig. 1. Among 32 included articles in the review, twenty-six studies were quantitative and mixed methods (21 quantitative and 5 mixed methods) and 6 studies were qualitative (Table 1a, Table 1b, Table 1c, Table 1d and 2). The design of all of the quantitative studies were cross-sectional. The majority of the qualitative studies were designed as in-depth interviews (n = 4), one of them as focus group discussions and the last one includes both in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. The proportion of HIV-positive women participating in cervical cancer screening, at least once in lifetime, ranged from 0.7% to 88%. Twelve studies focused on Pap test, three on visual inspection methods (VIA/VILI), three on visual inspection methods and Pap test, and 14 looked generally at cervical cancer screening without specifying a particular screening method. Forty-four percent of the studies were published in years 2018 or later, and twenty-nine studies were carried out in African, two in Asian and one in Southern American LMICs.

Fig. 1.

Literature search and review flowchart for selection of studies.

Table 1a.

Quantitative and mixed-method studies conducted in Western Africa.

| First author, year | Country | Study design | Study setting | Population | Age | Screening status | Type of screening | Patient-reported factors influencing women’s cervical cancer screening experience. The (+/−) signs indicate women’s perception of how these factors influenced their screening experience. | MMAT score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dim et al. (2009) | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT) clinic of the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital in Enugu, Nigeria | 150 HIV-positive women and 150 HIV-negative women | 21–54 years, mean age 34.9 year | 0.7% screened at least once | Pap test | Personal low awareness of cervical cancer (78%) (−), low perception about being at risk of cervical cancer among HIV-positive women (12.1%) (−), low awareness of pap-smear among HIV-positive women (4%) (−) | 50% |

| Adibe and Aluh (2018) | Nigeria | Descriptive cross-sectional study | ART clinic at the Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, tertiary health care in Nnewi, south-eastern Nigeria | 447 HIV-positive women | NR | 10% screened at least once | Pap test |

Personal not heard of cervical cancer screening (61.8%) (−), not heard of HPV (86.4%) (−), not heard of HPV vaccine (88.8%) (−), fear of screening procedure (1.8%) (−), screening not necessary (21%) (−), negative attitude toward screening (56.5%) (−), had a previous Pap test (+), had a previous gynecological visit (+), awareness on cervical cancer (+) Social information sources [media, (23%) and HCP (19.9%)] (+), bad attitude of nurses (0.7%) (−), discouraged by partner (1.3%) (−) Structural too expensive (0.9%) (−) |

75% |

| Ezechi et al. (2013) | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | HIV treatment center, Nigerian Institute of Medical Research (NIMR), Lagos |

1517 HIV-positive women | 18–57 years, mean age 31 year | 9.4% screened at least once | NR |

Personal awareness of cervical cancer (OR: 1.53) (+), fear of test outcome (4.2%) (−), pregnant/recently delivered (10.7%) (−) Social need to obtain partner’s approval (12.4%) (−), religious denial (14.0%) (−) Structural expensive cervical cancer screening (35.2%) (−), long waiting time (12.7%) (−) |

75% |

| Rabiu et al. (2011) | Nigeria | Descriptive cross-sectional study | ART clinic of the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital, Ikeja, Lagos State, Nigeria | 300 HIV-positive women | 17–60 years, mean age 34 year | 31.3% screened at least once | Pap test |

Personal never heard of cervical cancer (74.7%) (−), never heard of the Pap test (84%) (−), fear of the result (9.1), does not feel susceptible to cervical cancer (12.1) (−) Social information sources [media electronic and printed (33.3%), friends and relatives (20.8%), medical personnel (16.7%)] (+) Structural expensive cervical cancer screening (9.1%) (−) |

50% |

| Tchounga et al. (2019) | Ivory Coast (Côte d’Ivoire) | Cross-sectional study | Outpatient setting in the four highest volume urban HIV clinics of government’s or non-governmental organisation’s sector in Côte d’Ivoire | 1991 HIV-positive women | Inter Quartile Range of 37–47 years, median age 42 | 59.7% screened at least once | Pap test and VIA |

Personal being informed on cervical cancer at the HIV clinic (OR: 1.5) (+), clarity of information on cervical cancer (OR: 1.7) (+), identifying HIV as a risk factor for cervical cancer (OR: 1.4) (+), being proposed cervical cancer screening in the HIV clinic (OR: 10.1) (+), receiving advise for repeated cervical cancer screening over time (65.5%) (+), accept screening as part of a research project (15.8%) (+), lack of information about cervical cancer (54%) (−), fear of the result of screening (22%) (−), negligence (15%) (−) Structural fear of cervical cancer screening cost (10%) (−) |

75% |

| Ebu and Ogah (2018) | Ghana | Descriptive cross-sectional study | HIV health facilities in the Central Region of Ghana | 660 HIV-positive women | 20–65 years | NR | NR | Personal perceived Benefits of cervical cancer screening (OR: 1.68) (+), perceived Seriousness of cervical cancer (OR: 2.02) (+), cues about cervical cancer screening (OR :3.48) (+) | 100% |

| Stuart et al. (2019) | Ghana | Mixed methods | Cape Coast Teaching Hospital in Cape Coast, Ghana |

55 HIV-positive women and 76 HIV-negative women | Mean age 42.9 year | NR | NR |

Personal embarrassing (35.6%) (−), not painful examination based on previous experience with cervical cancer screening (85.0%) (+), worried about the results of screening (43.3%) (−) Social given enough information about HPV, cervical cancer, and screening before the screening (88.3%) (+) Structural would have cervical cancer screening again if it was free (91.4%) (+) |

50% |

ART anti-retroviral therapy, HCP healthcare provider, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, MMAT mixed methods appraisal tool, NR not reported, OR odds ratio, VIA visual inspection with acetic acid.

Table 1b.

Quantitative and mixed-method studies conducted in Southern Africa.

| First author, year | Country | Study design | Study setting | Population | Age | Screening status | Type of screening | Patient-reported factors influencing women’s cervical cancer screening experience. The (+/−) signs indicate women’s perception of how these factors influenced their screening experience. | MMAT score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Godfrey et al. (2019) | South Africa | Cross-sectional study | Secondary referral obstetrics and gynecology hospital, Lower Umfolozi District War Memorial Hospital, in rural KwaZulu-Natal | 79 HIV-positive women and 155 HIV-negative women | 18–70 years, mean age 29 year | 32.5% screened at least once | Pap test |

Personal never heard of a Pap test (27.1%) (−), too scared/too painful (19.4%) (−), never offered cervical cancer screening (12.9%) (−), feel well so do not need cervical cancer screening (being asymptomatic) (5.8%) (−), do not want to know the result (1.9%) (−), not old enough for cervical cancer screening (1.9%) (−), being symptomatic 57.9% (+) Social Offered to them by HCP (42.1%) (+) Structural did not know where or when to have cervical cancer screening (6.5%) (−), not enough time to get screened (5.8%) (−) |

75% |

| Lieber et al. (2019) | South Africa | Mixed-methods* | Rural HIV clinic in Limpopo Province, South Africa | 403 HIV-positive women for quantitative and 12 HIV-positive women for qualitative study | NR | NR | VIA and Pap test |

Personal discomfort with the position required for undergoing cervical cancer screening (−), knowledgeable about the purpose of VIA and pap test (+), left behind in follow-up care (−) Structural understaffing (−), long waiting time (−) |

25% |

| Maree and Moitse (2014) | South Africa | Descriptive cross-sectional study | Adult HIV unit at a publichospital in Johannesburg, South Africa | 315 HIV-positive women | 27–54 years, mean age 38.9 year | NR | Pap test |

Personal fear of the procedure (39.3%) (−), not ill so screening not necessary (7.4%) (−) Social information sources [nurse or doctor (61%), community health worker (50.8%), classmates (9.8%) and relative and parents (7.6%)] (+), bad attitude of nurses and doctors (8.1%) (−) |

50% |

| Wake et al. (2009) | South Africa | Cross-sectional study | ART clinic at GF Jooste Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa | 100 HIV-positive women | 21–64 years, mean age 32.8 year | 59% screened at least once | Pap test |

Personal had never been asked to get cervical cancer screening (35.7%) (−), had never heard of the Pap test (28.6%) (−), fear and misunderstanding of cervical cancer screening (−) Structural unable to attend cervical cancer screening due to inappropriate time and place (19.6%) (−) |

50% |

| Mingo et al. (2012) | Botswana | Cross-sectional study | Two public health clinics in Gaborone, Botswana | 163 HIV-positive women and 117 HIV-negative women | 20–84 years | 72% screened at least once | Pap test | Personal ever heard of cervical cancer (OR: 3.28) (+), to know if cervix is healthy (56%) (+), to get early treatment (34%) (+), improve overall health (33%) (+), being symptomatic (10%) (+), protecting future fertility/pregnancy (8%) (+) | 50% |

ART anti-retroviral therapy, HCP healthcare provider, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, MMAT mixed methods appraisal tool, NR not reported, OR odds ratio, VIA visual inspection with acetic acid

*Quantitative data of this mix-methods study is not presented since it was not patient-reported factors and it only reported patients’ medical records data.

Table 1c.

Quantitative and mixed-method studies conducted in Eastern Africa.

| First author, year | Country | Study design | Study setting | Population | Age | Screening status | Type of screening | Patient-reported factors influencing women’s cervical cancer screening experience. The (+/−) signs indicate women’s perception of how these factors influenced their screening experience. | MMAT score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assefa et al. (2019) | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | Three public health facilities providing both cervical cancer screening and assisted reproductive technology services in Hawassa, Ethiopia | 342 HIV-positive women | Mean age 33.4 year | 40.1% screened within previous five years | NR |

Personal no need for cervical cancer screening due to no symptoms (34.1%) (−), fear of test results (16.1%) (−), fear of painful examination (11.2%) (−), positive attitude towards cervical cancer and screening (+), knowledge about cervical cancer risk factors (+) Social partner or husband support (+) Structural do not know the place for cervical cancer screening (6.3%) (−), expensive (2%) (−) |

75% |

| Belete et al. (2015) | Ethiopia | Mixed methods | Public health institutions of HIV care in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia | 322 HIV-positive women for quantitative and 14 HIV-positive women for qualitative study | Mean age 35.7 years | 11.5% screened at least once | NR |

Personal being pregnant or in peripartum period (13.3%) (−), fear of test result (30.8%) (−), knowledge about risk factors and prevention of cervical cancer (+) Social information sources [media, (58.2%) and HCP (53.6%)] (+), partner acceptance (10%) (+), religious denial (10%) (−) Structural expensive cervical cancer screening (30%) (−), lack of female screeners (13.3%) (−), time consuming (35.8%) (−) |

75% |

| Erku et al. (2017) | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | ART clinic at University of Gondar Referral and Teaching Hospital, Ethiopia |

302 HIV-positive women | Mean age 33.7 year | 23.5% screened at least once | NR |

Personal comprehensive knowledge about cervical cancer screening (OR: 3.02) (+), perceived susceptibility of cervical cancer (OR: 2.85) (+), absence of symptoms (88.7%) (−), embarrassment (68.8%) (−), fear of test result (71%) (−), not prescribed by the doctor (32.9%) (−) Structural expensive cervical cancer screening (27.7%) (−), Screening center too far (37.7%) (−), time consuming (19%) (−) |

75% |

| Shiferaw et al. (2018) | Ethiopia | Mixed methods | Public (community) health centers in Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia | 581 HIV-positive women | 21–64 years, mean age 34.9 year | 10.8% screened at least once | NR |

Personal feeling healthy (36.5%) (−), never think of cervical cancer (23.9%) (−), lack of awareness about cervical cancer screening (9.6%) (−), embarrassing (5.5%) (−), fear of positive results (5.3%) (−), painful screening procedure (1.2%) (−) Social partner negative attitude toward cervical cancer screening (1.4%) (−), religion factors (0.9%) (−), HCP negative attitude (0.7%) (−), no appropriate care at health care facilities (6.2%) (−), HCP do not have good knowledge (1.4%) (−) Structural did not know where to get cervical cancer screening (20.1%) (−), expensive cervical cancer screening (5.7%) (−), no health facility in the catchment area (4.3%) (−) |

75% |

| Solomon et al. (2019) | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | Hospital based setting In Bishoftu town, East Shoa, Ethiopia | 475 HIV-positive women | 18–67 years, mean age 36.2 year | 24.8% screened at least once | VIA |

Personal fear of positive result (28%) (−), being symptomatic (33.1%) (+), perceived self-efficacy (OR: 1.24) (+), perceived threat of cervical cancer (OR: 1.08) (+), perceived net benefit (OR: 1.18) (+) Social information sources [HCP (81.2%), media printed and non-printed (15.9%), close relatives (2.9%)] (+), partner negative attitude toward cervical cancer screening (15%) (−), HCP advice on cervical cancer screening (64.4%) (+), relatives (family/friends) advice (2.5%) (+) |

100% |

| Njuguna et al. (2017) | Kenya | Mixed methods | Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya | 387 HIV-positive women for quantitative study and 4 focus group discussions (each group = 6–8 HIV-positive women) | Inter Quartile Range of 36–44 years, median age 40 | 46.3% screened at least once | NR |

Personal quality of information on cervical cancer screening services above average (OR 5.4–8.9) (+), had previous experience with cervical cancer screening before attending clinic (OR: 2.9) (+), fear of pain or excessive bleeding (−), young age and male gender of the HCP conducting the cervical cancer screening (−) Social cervical cancer screening recommended by HCP (OR: 10) (+) Structural long waiting time (−) |

50% |

| Rositch et al. (2012) | Kenya | Descriptive cross-sectional study | Voluntary counseling and testing centers in Nairobi, Kenya | 268 HIV-positive women and 141 HIV-negative women | Inter Quartile Range of 24–34 years, median age 28 | 14% screened at least once | Pap test |

Personal cervical cancer screening being part of routine care (42%) (+), cervical cancer screening being part of research study (19%) (+), being symptomatic (bleeding and abdominal pain) (6%) (+), did not know what cervical cancer screening is/why needed (78%) (−), knowledge of Pap test (OR: 1.8) (+), knowledge of HPV (OR: 1.7) (+), previous experience with Pap test (OR: 1.9) (+) Structural expensive cervical cancer screening (2%) (−), did not know where to get screened (4%) (−) |

75% |

| Rosser et al. (2015) | Kenya | Cross-sectional study | Integrated HIV clinic in the Nyanza Province of Kenya | 106 HIV-positive women | 23–64 years, mean age 34.9 year | 15% screened at least once | NR |

Personal screening by a male provider (8%) (−) Structural not willing to get screened if they had to pay (48%) (−) |

75% |

| Chipfuwa and Gundani (2013) | Zimbabwe | Descriptive cross-sectional study | Bindura Provincial Hospital, Zimbabwe | 70 HIV-positive women | 19–49 years, mean age 35.7 year | NR | NR |

Personal lack of Knowledge about risk factors of cervical cancer (90%) (−), low of perception about being at risk of cervical cancer among HIV-positive women (74.3%) (−), awareness of cervical cancer scored below the average (97.2%) (−) Social information sources [media, friends and relatives (40.5%), nurses (35.1%), general practitioner (10.8%), counselor (8.1%) and gynecologist (5.4%)] (+), lack of health education by HCP at clinic (97.1%) (−) |

25% |

| Koneru et al. (2017) | Tanzania | Cross-sectional study | HIV clinics in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 399 HIV-positive women | ≥19 years | 9% screened at least once | NR |

Personal had not been informed about care and treatment of cervical cancer at clinic (65.7%) (−) Social information sources [media (47.4%), hospital staff (39.3%), friends and families (4.8%)] (+), Structural free cervical cancer screening (83.3%) (+), free cervical cancer treatment (77.8%) (+), time to travel to clinic > 120 min (18.8%) (−) |

100% |

| Wanyenze et al. (2017) | Uganda | Nationwide cross-sectional study | 245 public and private HIV clinics across the five geographical regions (Central, Northern, Eastern, Western, and Kampala) in Uganda | 5198 HIV-positive women | 15–49 years | 30.3% screened at least once | NR |

Personal lack of information on cervical cancer screening (29.6%) (−), had been told that procedure is painful (10.5%) (−), fear of receiving a cancer diagnosis (40.6%) (−), embarrassing (22.3%) (−), knowledgeable of cervical cancer screening (PR: 2.19) (+), low risk perception (PR: 1.52) (+) Structural lack of screening facilities 14% (−), know any place where cervical cancer screening is offered (PR: 6.47) (+), did not have time (25.5%) (−) |

100% |

ART anti-retroviral therapy, HCP healthcare provider, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, MMAT mixed methods appraisal tool, NR not reported, PR prevalence ratio, OR odds ratio, VIA visual inspection with acetic acid.

Table 1d.

Quantitative and mixed-method studies conducted in other countries.

| First author, year | Country | Study design | Study setting | Population | Age | Screening status | Type of screening | Patient-reported factors influencing women’s cervical cancer screening experience. The (+/−) signs indicate women’s perception of how these factors influenced their screening experience. | MMAT score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belglaiaa et al. (2018) | Morocco | Cross-sectional study | HIV treatment center at the Hospital of Moulay Hassan Ben Elmehdi in Laâyoune city, Morocco | 115 HIV-positive women | Mean age 34.9 years | 13% screened at least once | Pap test |

Personal lack of knowledge of cervical cancer risk factors (79.1%) (−), absence of symptoms (47%) (−), never heard of a Pap test (22%) (−), fear of abnormal results (13%) (−), fear of painful sampling (7%), shame or embarrassment (7%) (−), absence of sexual activity (3%) (−) Social information sources [media, (17.4%), friends/family (2.6%), HCP (0.9%)] (+) |

50% |

| Delgado et al. (2017) | Peru | Cross-sectional study | Vía Libre non-governmental organization (NGO) HIV center in Lima, Peru | 71 HIV-positive women | 19–60 years, mean age 40.4 year | 12.7% never had a Pap test, 77.5% had over 1 year ago, 9.8% within 1 year | Pap test | Personal good knowledge on cervical cancer screening interval and frequency (75%) (+), low perception about being at risk of cervical cancer among HIV-positive women (37.5%) (−), good knowledge on certain types of the HPV that can cause cervical cancer (75%) (+) | 50% |

| Sichanh et al. (2014) | Laos | Cross-sectional case–control study | HIV treatment centers of three provinces of Lao PDR, Vientiane, Luang Prabang and Savannakhet | 320 HIV-positive women (cases) and 320 HIV-negative women (controls) | 25–63 years, mean age 36.2 year | 5.6% screened at least once | Pap test |

Personal no symptoms (46%) (−), never heard of cervical cancer screening (21.2%) (−), screening not necessary (10.9%) (−), not prescribed by the doctor (7.3%) (−) Structural not enough cervical cancer screening services available (5.6%) (−), |

100% |

HCP healthcare provider, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, MMAT mixed methods appraisal tool.

Table 2.

Qualitative studies included.

| First author, year | Country | Study design | Studysetting | Population | Age | Screening status | Type of screening | Patient-reported factors influencing women’s cervical cancer screening experience. The (+/−) signs indicate women’s perception of how these factors influenced their screening experience. | MMAT score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bateman et al. (2019) | Tanzania | Focus group discussions | Twelve Management and Development for Health (MDH) public HIV centers in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 19 HIV-positive women | 24–57 years | NR | NR |

Personal lack of knowledge on cervical cancer screening (−), fear of examination (−) Social information sources (+), participating in patient navigation programs (+), cancer-related stigma (−) |

75% |

| Bukirwa et al. (2015) | Uganda | In-depth interview | HIV specialist care organization of Mildmay Uganda | 18 HIV-positive women | ≥25 years | 1/3 not screened, 1/3 screened once, 1/3 screened on a regular basis | VILI, VIA |

Personal risk perception associated with HIV (+), misconceptions about the cervical cancer screening process (−), fear of painful examination and other screening-related side effects (−), current poor health status of the women (excessive weight loss, DM, HTN) (−), competing health priorities (tuberculosis and antiretroviral therapy) (−), embarrassment (−), poor hygiene (−) Social lack of health education (−), lack of a proper follow-up reminder (−) Structural long waiting time (−) |

100% |

| Gordon et al. (2019) | India | Semi-structured in-depth interviews | New Civil Hospital ART Centrein Surat, India | 25 HIV-positive women | 30–54 years, mean age 37.2 year | 88% screened at least once | Pap test |

Personal concerns about HIV status disclosure (−) Social HIV-related stigma at healthcare facilities (−), support from friends and/or family members (+), confidential communication with physician (+) |

75% |

| Matenge and Mash (2018) | Botswana | Semi-structured interviews | Oodi rural clinic in the Kgatleng district of Botswana | 14 HIV-positive women | 29–49 years, mean age 37.4 year | 71.4% screened at least once | Pap test and VIA |

Personal delays in getting the test results (−), being employed (−), getting an appointment for the cervical cancer screening (−), lack of instruction by HCP (−), lack of knowledge Pap test and risk factors of cervical cancer (−), fear of painful examination (−), embarrassment (−), fear from positive results (−), lack of knowledge about treatment modalities for precursor lesions of cervical cancer (−), alcohol misuse (−) Structural long distance from the clinic (−), unpredictability of public transport for the clinic (−), equipment shortages at the clinic (−), long waiting time (−) |

50% |

| Nyambe et al. (2018) | Zambia | In-depth interviews | Urban and rural health care facilities in Lusaka and Chongwe districts, Zambia | 19 HIV-positive women, 19 HIV-negative women and 2 women with unknown HIV status | 25–49 years | 52.5% screened at least once | NR | Personal importance of early detection of precancerous lesions (+), misconceptions about risk factors of cervical cancer (−), fear of painful examination (−), lack of time and reluctance (−) | 50% |

| White et al. (2012) | Zambia | Focus group discussions and in-depth interviews | Zambian Ministry of Health primary health center in Kanyama | 20 HIV positive women and 40 HIV-negative women | 18–49 years | NR | VIA |

Personal protecting future pregnancy (+), screening test was performed quickly (+), undressing for the exam (−), fear of painful examination (−), potential of contracting diseases from examination (−) Social supportive attitudes of staff (+), confidential communication with staff (+), encouragement from close friends and husbands (+), cancer-related stigma (−), Structural free healthcare services (+), understaffing (−) |

75% |

ART anti-retroviral therapy, HCP healthcare provider, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, MMAT mixed methods appraisal tool, NR not reported, VIA visual inspection with acetic acid, VILI visual inspection with Lugol’s iodine.

3.2. Patient-reported barriers and facilitators

3.2.1. Personal factors

Knowledge and attitude toward cervical cancer and screening

HIV-positive women with low knowledge of cervical cancer (Belglaiaa et al., 2018, Chipfuwa and Gundani, 2013, Dim et al., 2009, Koneru et al., 2017, Matenge and Mash, 2018, Rabiu et al., 2011, Tchounga et al., 2019) and cervical cancer screening (Dim et al., 2009, Matenge and Mash, 2018, Rabiu et al., 2011, Belglaiaa et al., 2018, Godfrey et al., 2019, Sichanh et al., 2014, Adibe and Aluh, 2018, Bateman et al., 2019, Rositch et al., 2012, Shiferaw et al., 2018, Wake et al., 2009, Wanyenze et al., 2017) were less likely to undergo screening. Conversely, adequate knowledge of cervical cancer (Tchounga et al., 2019, Adibe and Aluh, 2018, Assefa et al., 2019, Belete et al., 2015, Erku et al., 2017, Ezechi et al., 2013, Mingo et al., 2012) and cervical cancer screening (Rositch et al., 2012, Wanyenze et al., 2017, Erku et al., 2017, Delgado et al., 2017, Ebu and Ogah, 2018, Lieber et al., 2019;85(1), Njuguna et al., 2017) was associated with higher rates of cervical cancer screening uptake by patients. Two studies evaluated HIV-positive women’s attitudes toward cervical cancer screening and reported that positive attitude (Assefa et al., 2019), despite negative one (Adibe and Aluh, 2018), is associated with increased rate of cervical cancer screening uptake.

Perceived susceptibility of cervical cancer

The majority of studies showed a low perceived susceptibility of cervical cancer among HIV-positive women (Chipfuwa and Gundani, 2013, Dim et al., 2009, Rabiu et al., 2011, Wanyenze et al., 2017, Delgado et al., 2017). This low perceived susceptibility was associated with a decreased uptake of cervical cancer screening in most of studies, except for one study that showed low perceived susceptibility was significantly associated with higher uptake of cervical cancer screening (Wanyenze et al., 2017). On the other hand, a number of previous studies found that greater perceived susceptibility of cervical cancer was associated with increased uptake of cervical cancer screening by study subjects (Solomon et al., 2019, Erku et al., 2017, Bukirwa et al., 2015).

Embarrassment

Among included surveys, embarrassment/shame of showing private parts of body and pelvic examination were among main reasons for not seeking cervical cancer screening facilities, and this barrier’s prevalence ranged from 5.5% to 68.8% among respondents (Belglaiaa et al., 2018, Matenge and Mash, 2018, Shiferaw et al., 2018, Wanyenze et al., 2017, Erku et al., 2017, Bukirwa et al., 2015, Stuart et al., 2019, White et al., 2012). Additionally, the male gender of the healthcare provider (HCP) performing the cervical cancer screening appeared to be a barrier in uptake of cervical cancer screening by HIV-positive women (Njuguna et al., 2017, Rosser et al., 2015).

Fear of the screening procedure and test results

Most of studies reported fear of the screening procedure as a potential barrier to get screened among HIV-positive women (Belglaiaa et al., 2018, Godfrey et al., 2019, Matenge and Mash, 2018, Adibe and Aluh, 2018, Bateman et al., 2019, White et al., 2012, Maree and Moitse, 2014, Nyambe et al., 2018, Shiferaw et al., 2018, Wake et al., 2009, Wanyenze et al., 2017, Assefa et al., 2019, Lieber et al., 2019;85(1), Njuguna et al., 2017, Bukirwa et al., 2015). In most of the cases, this was related to the fear of painful pelvic examination, bleeding or contracting diseases through cervical cancer screening. Interestingly, one study reported that HIV-positive women with previous experience of cervical cancer screening, who reported painless and comfortable cervical cancer screening experience, were more likely to accept and undergo following cervical cancer screening (Stuart et al., 2019). Furthermore, fear of being diagnosed with cancer and fatalistic beliefs about cervical cancer make HIV-positive women less likely to go for a cervical cancer screening (Shiferaw et al., 2018, Stuart et al., 2019, Solomon et al., 2019, Belglaiaa et al., 2018, Godfrey et al., 2019, Matenge and Mash, 2018, Rabiu et al., 2011, Tchounga et al., 2019, Wanyenze et al., 2017, Assefa et al., 2019, Belete et al., 2015, Erku et al., 2017, Ezechi et al., 2013).

Experiencing cervical cancer-related symptoms

Being asymptomatic was identified as a barrier to cervical cancer screening in a large number of studies, as lack of symptoms was incorrectly considered a sign of well-being (Godfrey et al., 2019, Sichanh et al., 2014, Shiferaw et al., 2018, Assefa et al., 2019, Erku et al., 2017, Maree and Moitse, 2014). However, experiencing signs and symptoms of cervical cancer (mainly abdominal pain and bleeding) was a trigger for uptake of cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive women noted by three studies (Solomon et al., 2019, Rositch et al., 2012, Mingo et al., 2012).

Other self-reported personal factors influencing cervical cancer screening uptake

Previous experience of cervical cancer screening was reported as a facilitator for undergoing subsequent cervical cancer screenings (Adibe and Aluh, 2018, Rositch et al., 2012, Njuguna et al., 2017). Being pregnant or in peripartum period was a barrier to cervical cancer screening (Belete et al., 2015, Ezechi et al., 2013); however, desire for pregnancy in future and preserving fertility was a facilitator for cervical cancer screening uptake (Mingo et al., 2012, White et al., 2012). Current medical illnesses (such as advanced stage of AIDS, diabetes or hypertension, etc.) and health priorities other than cervical cancer were considered as screening barriers by HIV-positive women (Bukirwa et al., 2015).

3.2.2. Social factors

Patient–HCP relationship

The effectiveness of the patient–HCP relationship was acknowledged as having a significant effect on cervical cancer screening uptake. Accordingly, women who were well informed by their HCPs regarding the cervical cancer and screening methods were more likely to get screened (Solomon et al., 2019, Godfrey et al., 2019, Njuguna et al., 2017, Stuart et al., 2019, White et al., 2012, Gordon et al., 2019). In contrast, poor patient-HCP relationship and negative attitude of HCPs toward HIV-positive women were considered a barrier toward cervical cancer screening uptake (Adibe and Aluh, 2018, Shiferaw et al., 2018, Maree and Moitse, 2014).

Stigma

Fear of cancer-related stigma lead to patients avoiding cervical cancer screening (Bateman et al., 2019, White et al., 2012). Also, HIV related stigma and concerns regarding HIV status disclosure were mentioned as barriers to cervical cancer screening (Gordon et al., 2019).

Information sources

There seems to be a variety of information sources for cervical cancer and its screening such as media, HCPs, family and friends, and etc. The majority of studies noted media as the main information source (Belglaiaa et al., 2018, Chipfuwa and Gundani, 2013, Koneru et al., 2017, Rabiu et al., 2011, Adibe and Aluh, 2018, Belete et al., 2015), while a lower number of studies noted HCPs as the main sources of information on cervical cancer (Solomon et al., 2019, Maree and Moitse, 2014).

Social support from friends and family members

Encouragement from family members to attend screening, particularly spousal encouragement, was an important motivator for women (Solomon et al., 2019, Assefa et al., 2019, Belete et al., 2015, White et al., 2012, Gordon et al., 2019). Women who reported negative attitude of their husband/partner toward cervical cancer screening were less likely to undergo screening (Adibe and Aluh, 2018, Shiferaw et al., 2018, Ezechi et al., 2013).

Other self-reported social factors influencing cervical cancer screening uptake

Religious beliefs and values seem to influence the uptake of cervical cancer screening across the ethnic and racial diversity of HIV-positive women (Belete et al., 2015, Ezechi et al., 2013). In the latter studies, some participants share concerns for maintaining modesty during cervical cancer screening.

3.2.3. Structural factors

Screening costs

HIV-positive women from ten studies specified that financial issues and screening costs were a barrier to cervical cancer screening (Rositch et al., 2012, Shiferaw et al., 2018, Rosser et al., 2015, Rabiu et al., 2011, Tchounga et al., 2019, Adibe and Aluh, 2018, Assefa et al., 2019, Belete et al., 2015, Erku et al., 2017, Ezechi et al., 2013), while a free screening opportunity was associated with an increased interest of women to get screened for cervical cancer (White et al., 2012). In another report by Stuart et al. (Stuart et al., 2019), 91.4% of HIV-positive women noted that if screening was free, they would do it again. Free cervical cancer screening and cancer-treatment was noted as a facilitator of screening uptake in one study (Koneru et al., 2017).

Healthcare facility accessibility and time issues

Not knowing a place where cervical cancer screening is done or being out of catchment of a healthcare facility providing screening services were among barriers to uptake of cervical cancer screening (Godfrey et al., 2019, Sichanh et al., 2014, Matenge and Mash, 2018, Assefa et al., 2019, Erku et al., 2017, Rositch et al., 2012, Shiferaw et al., 2018, Wake et al., 2009). Time limitations and long waiting time at clinics were noted as barriers by a majority of women (Godfrey et al., 2019, Koneru et al., 2017, Matenge and Mash, 2018, Wake et al., 2009, Wanyenze et al., 2017, Nyambe et al., 2018, Belete et al., 2015, Erku et al., 2017, Ezechi et al., 2013, Lieber et al., 2019;85(1), Njuguna et al., 2017, Bukirwa et al., 2015).

Resources/infrastructures

Lack of facilities needed for cervical cancer screening (Matenge and Mash, 2018, Wanyenze et al., 2017) and understaffing (Belete et al., 2015, Lieber et al., 2019;85(1), White et al., 2012) were other two barriers to cervical cancer screening.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review to summarize only the patient-reported factors influencing cervical cancer screening uptake by HIV-positive women in LMICs. The results of included studies suggest that the rates of uptake of cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive patients from LMICs were below the national and global recommendations. HIV-positive women most commonly highlighted personal (knowledge and attitude, perceived susceptibility, embarrassment and fear of the procedure and test results), social (patient–HCP relationship, stigma, information sources, support from family/friends and religious factors) and structural (costs, accessibility and time issues, resources and infrastructure) variables as key factors playing a prominent role in their screening decision making.

The WHO recommends that > 80% of women ages 35–59 years should have been screened at least once during their lifetime (World Health Organization, 2006). Furthermore, some strategic actions have been taken in order to achieve this goal, such as integration of cervical cancer prevention programs with HIV/AIDS care (Sahasrabuddhe et al., 2012). However, the low rates of cervical cancer screening uptake in LMICs indicates the failure in the implementation of screening programs in such a substantial scale in these countries (Sahasrabuddhe et al., 2012).

Our findings are to some extent consistent with the results of a previous systematic review, which analyzed the barriers associated with cervical cancer screening uptake in LMICs. Lack of knowledge and awareness, psychological (embarrassment or shyness), structural, sociocultural and religious barriers were among the most commonly reported factors influencing women’s decision to undergo cervical cancer screening (Devarapalli et al., 2018). In another review by McFarland et al. (McFarland et al., 2016) evaluating barriers to Pap test screening among women living in sub‐Saharan Africa, reported individuals’ barriers were lack of knowledge and awareness about Pap test, fear of cancer, belief of not being at risk for cervical cancer, and that a Pap test is not important unless being symptomatic and cultural or religious factors. Provider-level barriers were failure to inform or encourage women to get cervical cancer screening. Major system-related barriers were low availability and accessibility of the cervical cancer screening. However, in contrast to our review, previous reviews did not exclusively focus on HIV-positive women to identify whether they have different barriers or information needs regarding cervical cancer screening uptake.

There seems to be considerable overlap between the HIV-positive and HIV-negative population in terms of barriers influencing their uptake of cervical cancer screening. For instance, in a non-HIV cohort of women, similar to our findings, lack of knowledge about cervical cancer risk factors, treatment, and prevention strategies, painful screening experiences, embarrassment and other personal and institutional barriers were noted as common challenges affecting cervical cancer screening (Ebu et al., 2015).

Despite previous well-established challenges in cervical cancer screening among general population, HIV-related stigma is a unique barrier exclusively affecting HIV-positive women (Gordon et al., 2019). A high proportion of HIV-positive women have noted facing HIV-stigma both in healthcare settings and community contexts (Gordon et al., 2019, Valencia-Garcia et al., 2017). These concerns include being treated poorly by HCPs and being rejected or loss the support of families or friends after HIV-status disclosure. Unfortunately, the vicious cycle of HIV-stigma and lack of HIV status disclosure is a barrier negatively affecting cervical cancer screening uptake, leading to smaller number of HIV-positive women obtaining recommended cervical cancer care (both prevention and treatment) (Gordon et al., 2019). Previous research noted that discrimination and stigma against HIV-positive women are more prevalent in LMICs (Genberg et al., 2008); therefore, this review’s findings highlights that prompt actions must be taken in order to decrease HIV-related stigma and discrimination and increase the delivery of recommended health care to HIV-positive women.

Strengths and limitations

This review was the first of its kind to assess patient-reported barriers/facilitators to uptake of cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive women in LMICs. This review highlights the perspectives of HIV-positive women and thus could be used as a valuable resource for further research and health promotion actions. This collective evidence has fundamental implications for education, policy, and further research. Our review was limited by the variable quality of included studies.

5. Conclusions

This review has raised numerous barriers and facilitators at personal, social and structural levels hindering the use of cervical cancer screening services among HIV-positive women in LMICs. This provides concrete evidence for the use of multilevel strategies, by targeting health professionals, policy-makers, patients and their families, in order to promote the uptake of cervical cancer screening services by HIV-positive women in countries with limited resources.

Authors contributions

Original concept, MK and KH.

Database search, MK and KH.

Data extraction, MK, HV and NA.

Preparation of the primary manuscript drafts, KH, LF, SR and KB.

Critical review and preparation of final manuscript, HV, NA, LF, SR and KB.

All authors read the final version of manuscript and approved it for submission.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adibe M.O., Aluh D.O. Awareness, knowledge and attitudes towards cervical cancer amongst HIV-positive women receiving care in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. J. Cancer Educ. 2018;33(6):1189–1194. doi: 10.1007/s13187-017-1229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assefa A.A., Astawesegn F.H., Eshetu B. Cervical cancer screening service utilization and associated factors among HIV positive women attending adult ART clinic in public health facilities, Hawassa town, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019;19(1):847. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4718-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey H., Thorne C., Semenenko I., Malyuta R., Tereschenko R., Adeyanova I. Cervical screening within HIV care: findings from an HIV-positive cohort in Ukraine. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034706. e34706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman L.B., Blakemore S., Koneru A., Mtesigwa T., McCree R., Lisovicz N.F. Barriers and facilitators to cervical cancer screening, diagnosis, follow-up care and treatment: perspectives of human immunodeficiency virus-positive women and health care practitioners in Tanzania. Oncologist. 2019;24(1):69–75. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belete N., Tsige Y., Mellie H. Willingness and acceptability of cervical cancer screening among women living with HIV/AIDS in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Gynecol. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2015;2:6. doi: 10.1186/s40661-015-0012-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belglaiaa E., Souho T., Badaoui L., Segondy M., Pretet J.L., Guenat D. Awareness of cervical cancer among women attending an HIV treatment centre: a cross-sectional study from Morocco. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020343. e020343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet F., Lewden C., May T., Heripret L., Jougla E., Bevilacqua S. Malignancy-related causes of death in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Cancer. 2004;101(2):317–324. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukirwa A., Mutyoba J.N., Mukasa B.N., Karamagi Y., Odiit M., Kawuma E. Motivations and barriers to cervical cancer screening among HIV infected women in HIV care: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:82. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0243-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catarino R., Petignat P., Dongui G., Vassilakos P. Cervical cancer screening in developing countries at a crossroad: Emerging technologies and policy choices. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;6(6):281–290. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v6.i6.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipfuwa T., Gundani H.V. Mashonaland Central Province; Zimbabwe: 2013. Awareness of cervical cancer in HIV positive women aged 18 to 49 years at Bindura Provincial Hospital. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford G.M., Franceschi S., Keiser O., Schoni-Affolter F., Lise M., Dehler S. Immunodeficiency and the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3 and cervical cancer: A nested case-control study in the Swiss HIV cohort study. Int. J. Cancer. 2016;138(7):1732–1740. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado J.R., Menacho L., Segura E.R., Roman F., Cabello R. Cervical cancer screening practices, knowledge of screening and risk, and highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence among women living with human immunodeficiency virus in Lima, Peru. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2017;28(3):290–293. doi: 10.1177/0956462416678121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devarapalli P., Labani S., Nagarjuna N., Panchal P., Asthana S. Barriers affecting uptake of cervical cancer screening in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Indian J. Cancer. 2018;55(4):318. doi: 10.4103/ijc.IJC_253_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dim C.C., Dim N.R., Ezegwui H.U., Ikeme A.C. An unmet cancer screening need of HIV-positive women in southeastern Nigeria. Medscape J. Med. 2009;11(1):19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryden-Peterson S., Bvochora-Nsingo M., Suneja G., Efstathiou J.A., Grover S., Chiyapo S. HIV infection and survival among women with cervical cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34(31):3749–3757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.9613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebu N.I., Ogah J.K. Predictors of cervical cancer screening intention of HIV-positive women in the central region of Ghana. BMC Women's Health. 2018;18(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0534-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebu N.I., Mupepi S.C., Siakwa M.P., Sampselle C.M. Knowledge, practice, and barriers toward cervical cancer screening in Elmina, Southern Ghana. Int. J. Women's Health. 2015;7:31. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S71797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erku D.A., Netere A.K., Mersha A.G., Abebe S.A., Mekuria A.B., Belachew S.A. Comprehensive knowledge and uptake of cervical cancer screening is low among women living with HIV/AIDS in Northwest Ethiopia. Gynecol. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2017;4:20. doi: 10.1186/s40661-017-0057-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezechi O.C., Gab-Okafor C.V., Ostergren P.O., Odberg Pettersson K. Willingness and acceptability of cervical cancer screening among HIV positive Nigerian women. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Dikshit R., Eser S., Mathers C., Rebelo M. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genberg B.L., Kawichai S., Chingono A., Sendah M., Chariyalertsak S., Konda K.A. Assessing HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination in developing countries. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(5):772–780. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9340-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey M.A.L., Mathenjwa S., Mayat N. Rural Zulu women's knowledge of and attitudes towards Pap smears and adherence to cervical screening. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2019;11(1):e1–e6. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v11i1.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J.R., Barve A., Chaudhari V., Kosambiya J.K., Kumar A., Gamit S. “HIV is not an easily acceptable disease”: the role of HIV-related stigma in obtaining cervical cancer screening in India. Women Health. 2019;59(7):801–814. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2019.1565903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koneru A., Jolly P.E., Blakemore S., McCree R., Lisovicz N.F., Aris E.A. Acceptance of peer navigators to reduce barriers to cervical cancer screening and treatment among women with HIV infection in Tanzania. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2017;138(1):53–61. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber M., Afzal O., Shaia K., Mandelberger A., Du Preez C., Beddoe A.M. Cervical cancer screening in HIV-positive farmers in South Africa: mixed-method assessment. Ann. Glob. Health. 2019;85(1) doi: 10.5334/aogh.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maree J.E., Moitse K.A. Exploration of knowledge of cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening amongst HIV-positive women. Curationis. 2014;37(1):1209. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v37i1.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massad L.S., Ahdieh L., Benning L., Minkoff H., Greenblatt R.M., Watts H. Evolution of cervical abnormalities among women with HIV- 1: evidence from surveillance cytology in the women's interagency HIV study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2001;27(5):432–442. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200108150-00003. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matenge T.G., Mash B. Barriers to accessing cervical cancer screening among HIV positive women in Kgatleng district, Botswana: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205425. e0205425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland D.M., Gueldner S.M., Mogobe K.D. Integrated review of barriers to cervical cancer screening in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2016;48(5):490–498. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingo A.M., Panozzo C.A., DiAngi Y.T., Smith J.S., Steenhoff A.P., Ramogola-Masire D. Cervical cancer awareness and screening in Botswana. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2012;22(4):638–644. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e318249470a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njuguna E., Ilovi S., Muiruri P., Mutai K., Kinuthia J., Njoroge P. Factors influencing cervical cancer screening in a Kenyan health facility: a mixed qualitative and quantitative study. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;6(4):1180–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Nyambe N., Hoover S., Pinder L.F., Chibwesha C.J., Kapambwe S., Parham G. Differences in cervical cancer screening knowledge and practices by HIV status and geographic location: implication for program implementation in Zambia. Afr. J. Reprod. Health. 2018;22(4):92–101. doi: 10.29063/ajrh2018/v22i4.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunwale A.N., Coleman M.A., Sangi-Haghpeykar H., Valverde I., Montealegre J., Jibaja-Weiss M. Assessment of factors impacting cervical cancer screening among low-income women living with HIV-AIDS. AIDS Care. 2016;28(4):491–494. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1100703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace R., Pluye P., Bartlett G., Macaulay A.C., Salsberg J., Jagosh J. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012;49(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiu K.A., Akinbami A.A., Adewunmi A.A., Akinola O.I., Wright K.O. The need to incorporate routine cervical cancer counselling and screening in the management of HIV positive women in Nigeria. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2011;12(5):1211–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rositch A.F., Gatuguta A., Choi R.Y., Guthrie B.L., Mackelprang R.D., Bosire R. Knowledge and acceptability of pap smears, self-sampling and HPV vaccination among adult women in Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040766. e40766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosser J.I., Njoroge B., Huchko M.J. Cervical cancer screening knowledge and behavior among women attending an urban HIV clinic in western Kenya. J. Cancer Educ. 2015;30(3):567–572. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0787-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahasrabuddhe V.V., Parham G.P., Mwanahamuntu M.H., Vermund S.H. Cervical cancer prevention in low-and middle-income countries: feasible, affordable, essential. Cancer Prevention Res. 2012;5(1):11–17. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S., Montgomery H., Smith C., Madge S., Walker P., Evans H. Cervical screening in HIV-positive women: characteristics of those who default and attitudes towards screening. HIV Med. 2006;7(1):46–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin S. Temple University Press; 1998. The Politics of Women's Health: Exploring Agency and Autonomy. [Google Scholar]

- Shiferaw S., Addissie A., Gizaw M., Hirpa S., Ayele W., Getachew S. Knowledge about cervical cancer and barriers toward cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive women attending public health centers in Addis Ababa city. Ethiopia. Cancer Med. 2018;7(3):903–912. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sichanh C., Quet F., Chanthavilay P., Diendere J., Latthaphasavang V., Longuet C. Knowledge, awareness and attitudes about cervical cancer among women attending or not an HIV treatment center in Lao PDR. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon K., Tamire M., Kaba M. Predictors of cervical cancer screening practice among HIV positive women attending adult anti-retroviral treatment clinics in Bishoftu town, Ethiopia: the application of a health belief model. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):989. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6171-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart A., Obiri-Yeboah D., Adu-Sarkodie Y., Hayfron-Benjamin A., Akorsu A.D., Mayaud P. Knowledge and experience of a cohort of HIV-positive and HIV-negative Ghanaian women after undergoing human papillomavirus and cervical cancer screening. BMC Women's Health. 2019;19(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0818-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchounga B., Boni S.P., Koffi J.J., Horo A.G., Tanon A., Messou E. Cervical cancer screening uptake and correlates among HIV-infected women: a cross-sectional survey in Côte d'Ivoire, West Africa. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029882. e029882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tello M.A., Jenckes M., Gaver J., Anderson J.R., Moore R.D., Chander G. Barriers to recommended gynecologic care in an urban United States HIV clinic. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19(8):1511–1518. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Garcia D., Rao D., Strick L., Simoni J.M. Women's experiences with HIV-related stigma from health care providers in Lima, Peru:“I would rather die than go back for care”. Health Care Women Int. 2017;38(2):144–158. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2016.1217863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wake R.M., Rebe K., Burch V.C. Patient perception of cervical screening among women living with human immuno-deficiency virus infection attending an antiretroviral therapy clinic in urban South Africa. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2009;29(1):44–48. doi: 10.1080/01443610802484070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanyenze R.K., Bwanika J.B., Beyeza-Kashesya J., Mugerwa S., Arinaitwe J., Matovu J.K.B. Uptake and correlates of cervical cancer screening among HIV-infected women attending HIV care in Uganda. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1380361. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1380361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H.L., Mulambia C., Sinkala M., Mwanahamuntu M.H., Parham G.P., Kapambwe S. Motivations and experiences of women who accessed “see and treat” cervical cancer prevention services in Zambia. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012;33(2):91–98. doi: 10.3109/0167482X.2012.656161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Reproductive Health, World Health Organization, World Health Organization. Chronic Diseases, Health Promotion. Comprehensive cervical cancer control: a guide to essential practice. World Health Organization, 2006.