Abstract

Health information technology (HIT) has great potential for increasing patient engagement. Pediatric HCT is a setting ripe for using HIT but in which little research exists. “BMT Roadmap” is a web-based application that integrates patient-specific information and includes several domains: laboratory results, medications, clinical trial details, photos of the healthcare team, trajectory of transplant process, and discharge checklist. BMT Roadmap was provided to 10 caregivers of patients undergoing first-time HCT. Research assistants performed weekly qualitative interviews throughout the patient’s hospitalization, and at discharge and day 100, to assess the impact of BMT Roadmap. Rigorous thematic analysis revealed 5 recurrent themes: emotional impact of the HCT process itself; critical importance of communication among patients, caregivers and healthcare providers; ways in which BMT Roadmap was helpful during inpatient setting; suggestions for improvement of BMT Roadmap; and other strategies for organization and management of complex healthcare needs that could be incorporated into BMT Roadmap. Caregivers found the tool useful and easy-to-use, leading them to want even greater access to information. BMT Roadmap was feasible, with no disruption to inpatient care. While this initial study is limited by the small sample size and single institution experience, these initial findings are encouragning and support further investigation.

INTRODUCTION

One of the basic principles for designing a patient-centered healthcare system is allowing for the continuous, unfettered bi-drectional flow of clinical information and knowledge between patient and provider.1 However, few healthcare organizations have the infrastructure to support individuals with chronic medical conditions in this patient-centered fashion. Pediatric hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) is a medically complex and high-stakes procedure. A dedicated, 24/7, caregiver is necessary and expected in BMT. Oftentimes, a caregiver is tasked with monitoring treatment side effects, managing symptom burden, making treatment decisions, administering medications, and performing medical tasks (e.g., central line care and dressing changes). As such, the HCT trajectory may be long and unpredictable,2 which creates a complex and multifaceted caregiving process. Caregivers become overwhelmed and juggle multiple roles: i) “interpreter” of medical information; ii) “organizer” of medical appointments and juggling the needs of other family members; and iii) “clinician” to assess and identify health changes in the patient.3

We have previously shown that: 1) caregivers of pediatric HCT patients desire more information and support throughout their healthcare trajectory;4 and 2) technology could support this unmet informational need (Phase 1).5 A paper prototype of a health information technology (HIT) tool, “BMT Roadmap”, was developed to meet these needs. We then took the important step in gaining end-user feedback of our paper-based prototype; getting feedback from patients and caregivers in the design of our HIT using both low-fidelity and high-fidelity prototypes (Phase 2).6

These studies eventually lead to the development of “BMT Roadmap,” a HIT tool delivered on a consumer friendly tablet computer (Apple iPad®) that integrates patient-specific health information.7 BMT Roadmap included the following domains: i) real-time laboratory results which families could view even before the clinical team; ii) medications, with plain language summaries of common toxicities, indications for use, and instructions for administration; iii) clinical trials in which the patient was enrolled accompanied by a one-page plain language study summary; iv) healthcare provider directory with “yearbook-style” photos; v) visual depiction of the trajectory of HCT or “Phases of Care” as patients progress through the inpatient hospitalization; and vi) interactive discharge checklist that incorporates educational videos to prepare families for discharge (e.g.,central line care). Herein, we report the implementation of Phase 3 of our research, a qualitative study based on semi-structured interviews conducted in caregivers who used BMT Roadmap throughout the patients’ hospitalization. Unlike Phase 1 and 2 where we evaluated HIT prototypes, we now report on a study of BMT Roadmap conducted in real-time among caregivers of patients undergoing HCT.

METHODS

This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB number HUM00100126) and registered under ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02409121). This work is the final part of a 3-phase project, as described previously6 (Supplemental Data 1. BMT Roadmap Project: Phases 1, 2, and 3). In Phase 1, an experimental paper-based prototype of BMT Roadmap was developed.4, 5, 8, 9 In Phase 2, design session were conducted with patients and caregiveers using multiple prototypes.6, 7 In Phase 3 (the present study), we examined the implementation of BMT Roadmap in the inpatient setting, performing semi-structured qualitative interviews of caregivers of pediatric HCT patients and healthcare professionals to assess for recurring themes regarding the use of HIT during the HCT process. Participants were recruited by HCT nurse coordinators and physicians during the “Pre-Transplant Work-Up” stage in the ambulatory care setting prior to admission to the Pediatric HCT Unit (Supplemental Data 2. BMT Roadmap Brochure). The a priori sample size to assess feasibility of implementing the tool and conducting user assessments was a target of 10 caregivers. Eligibility included: i) adult caregiver (age ≥ 18 years) of any pediatric patient (age ≤ 25 years) undergoing first-time autologous or allogeneic HCT; ii) ability to speak and read in English; iii) willing and able to provide informed consent; and iv) willing to comply with study procedures and reporting requirements. Once enrolled, the Research Coordinator provided a tutorial on using the BMT Roadmap. Participants were allowed to use the device freely throughout the child’s hospital stay.

Qualitative Assessment

In-depth, semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted in 10 caregivers by four trained research assistants at baseline, weekly during admission, at discharge, and at day 100 post-HCT. The goal of these interviews was to unearth commonly held views and perspectives on the use of a patient-centered HIT tool and to identify opportunities for improvement. Open-ended, semi-structured interviews were also conducted in 12 healthcare providers to assess their perspectives on BMT Roadmap and its intended use or on any perceived workflow changes related to the tool. Healthcare provider interviews included physicians (N=5 HCT physicians), staff nurses (N=3), nurse specialists/educators (N=2), advanced practice nurse (N=1), and a social worker (N=1). Adapted from Piette et al,10 a priori domains to elicit caregivers’ and healthcare perceptions were assessed in open-ended questions (Supplementary Data 3. Qualitative Assessment Domains; Supplemental Data 4. Semi-Structured Interview Guide in Caregivers; and Supplementary Data 5. Semi-Structured Interview Guide in Healthcare Providers).

Data Analysis

The interviews were audio-recorded with permission, de-identified, and professionally transcribed. The transcriptions were reviewed with a minimum of three study team members and analyzed using a deductive and inductive approach utilizes best practices for qualitative research.11 Participants were probed to allow the study team to better understand how BMT Roadmap was received and delivered in an actual complex care setting.12 Qualitative thematic analysis of the data was performed through iterative cycles of coding and data collection.13 Codebook structures were refined to reflect emerging themes until consensus of a final codebook scheme was achieved (Supplemental Data 6. Codebook).14

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics and Use of BMT Roadmap

Ten caregivers of pediatric patients undergoing first-time autologous or allogeneic HCT enrolled in this study. As shown in Table 1, the median age of the caregiver population was 35 years (range, 25 - 54 years). A majority of caregivers were Caucasian (90%) and female (80%). Transplants were 50% autologous and 50% allogeneic. The diagnoses were heterogeneous and included acute lymphoblastic leukemia (N=2), acute myelogenous leukemia (N=1), myelodysplastic syndrome (N=1), severe congenital neutropenia (N=1), choroid plexus carcinoma (n=1), Ewing’s sarcoma (N=1), and neuroblastoma (n=3). The median hospital length of stay was 29.5 days (range, 20 – 117). BMT Roadmap was used frequently. Minutes used and days used were strongly inter-correlated (r=.90, p=0.001) and correlated with inpatient days (r=.70, p=0.05; and r=.81, p=0.01 respectively). The most time spent was in the laboratory module, followed by healthcare provider directory, medication, and phases of care modules.

Table 1.

Demographics and Time Stamps of BMT Roadmap Modules Used by Caregivers

| ID | CG Age |

CG Sex |

CG Race |

Patient Age (years) |

Patient Sex |

Patient Disease |

Type of transplant |

Engraft (days) |

Length of stay (days) |

Days with iPad |

Days using iPad |

Total (min) |

Labs (min) |

Meds (min) |

Directory (min) |

Phases (min) |

Discharge Checklist (min) |

Videos (min) |

Other (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG01 | 35 | M | White | 9 | F | ALL | Mismatched unrelated | 15 | 57 | 58* | 54 | 256.2 | 172.9 | 26.0 | 15.7 | 8.9 | 0.7 | 3.3 | 28.7 |

| CG02 | 25 | F | White | 3 | F | NBL | Autologous | 12 | 20 | 21 | 2 | 6.4 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.2 |

| CG03 | 40 | F | White | 10 | F | Carcinoma | Autologous | 12 | 21 | 22 | 21 | 123.4 | 60.0 | 4.5 | 11.9 | 7.9 | 0.1 | 11.0 | 28.1 |

| CG04 | 28 | F | White | 6 | M | MDS | Matched, unrelated | 14 | 28 | 29 | 14 | 50.1 | 10.7 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 11.6 | 2.0 | 0 | 19.1 |

| CG05 | 31 | F | White | 9 | M | ES | Autologous | 12 | 29 | 30 | 10 | 105.8 | 33.0 | 17.5 | 15.9 | 15.5 | 0.2 | 0 | 23.6 |

| CG06 | 34 | F | Asian | 7 | M | NBL | Autologous | 19 | 23 | 24 | 22 | 102.5 | 67.4 | 5.1 | 14.0 | 3.3 | 0 | 0 | 12.8 |

| CG07 | 26 | F | White | 3 | M | NBL | Autologous | 12 | 30 | 31 | 7 | 17.8 | 7.3 | 0.6 | 4.7 | 3.4 | 0 | 0 | 1.8 |

| CG08 | 54 | M | White | 18 | F | AML | Matched, related | 13 | 28 | 29 | 25 | 51.7 | 22.7 | 1.9 | 12.6 | 7.6 | 1.0 | 0 | 6.1 |

| CG09 | 43 | F | White | 16 | M | SCN | Matched, related | 12 | 34 | 35 | 25 | 110.2 | 41.2 | 16.8 | 5.0 | 11.2 | 2.8 | 14.8 | 18.4 |

| CG10 | 48 | F | White | 19 | M | ALL | Matched, unrelated | 16 | 117 | 68* | 41 | 153.3 | 44.2 | 11.5 | 16.4 | 16.5 | 0.5 | 8.4 | 55.9 |

CG = caregiver; F = female; M = male; ALL = acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML = acute myelogenous leukemia; Carcinoma = choroid plexus carcinoma; ES = Ewing’s sarcoma; NBL = neuroblastoma; SCN = severe congenital neutropenia; Min = minutes. “Total minutes” refers to the total time spent using any component of BMT Roadmap. Each subsequent column represents the total time (in minutes) using the various modules within BMT Roadmap. Other” includes modules, such as clinical trial information as well as the Home Page.

The BMT Roadmap program had a maximum of day 45 post-HCT in pulling real-time laboratory data, which was designed a priori. This affected two subjects where length of hospital was beyond day 45 post-HCT.

Qualitative Findings

Qualitative analyses revealed a wide range of user responses. We focused on 5 important themes that emerged during the qualitative assessment of caregivers throughout their childrens’ hospitalization: i) emotions associated with the HCT process itself; ii) communication between patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers; iii) Roadmap use in the inpatient setting; iv) suggestions for improving Roadmap; and v) organization and management of patient healthcare.

Emotions

In baseline interviews prior to using BMT Roadmap, a wide range of emotions were expressed by caregivers undergoing the HCT process. By the time patients were admitted for HCT, a majority (80%) had received intensive chemotherapy for their underlying malignancy and many of the caregivers reported being emotionally drained. While caregivers understood the risks and complications associated with HCT, undergoing the process itself was overwhelming: “Yes. He’s maxed out. We all are maxed out…It’s getting rough.”

Caregivers also described how their “new norm” had become caring for the patient and coming back and forth to the hospital for various clinic appointments, while also balancing other household commitments and tasks: “It’s our normal life now, so if we ever do go back to that normal that everybody thinks is normal, it’s going to be a bit awkward for us because we’ve always been back and forth to doctors’ appointments and hospitals.”

Communication

Caregivers described the importance of communication among patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers. Many described their own methods to learn more about HCT complications, which included the internet. Caregivers supported the concept of having a relationship with their healthcare provider as providing a more personable understanding of their child’s healthcare. A caregiver explained how BMT Roadmap facilitated positive interactions: “You don’t want to be a parent and have just found out your kid has cancer and be all alone on Google… So to have a more personable [BMT Roadmap]…with pictures is very helpful. Otherwise, you end up on WebMD, where everybody dies of everything.”

Caregivers reported how BMT Roadmap allowed them to return to patient-specific information on their own time (e.g., many hours after morning rounds) in order to communicate back to family members when they asked about specific details. Caregivers liked the descriptions and graphical metaphors of what to expect during a specific time point in transplant, because the modules served as visual aids to explain difficult information to a child. Interestingly, some caregivers stated they wanted as much information about HCT as possible, and were pleased that they could go back to BMT Roadmap to process the information at a later time: “The counts. They’ll mention them to me, but I need to see…Everything is way over my head. Being able to see it when I need to or when someone asks me is awesome.” Previously, healthcare providers controlled the information offered to families during morning rounds. Healthcare providers initially voiced concerns about providing real-time health information through BMT Roadmap. However, over time the tool was used as a platform for teaching: “As a nurse at the bedside I would want to say, “Hey let’s get out your tablet. Have you looked at it? Do you have any questions? Let’s look and see what the counts are today and we can talk off of that. On the meds we’re giving let’s look them up.” (Nurse)

With BMT Roadmap, caregivers had access to all of the daily laboratory results at the same time as, and sometimes before, the healthcare providers. While there was initial reluctance in providing such data, once BMT Roadmap was implemented and used in caregivers, the perceived workflow of healthcare providers did not appear to be impacted. Additional representative provider quotes are provided in Table 2: “She is sleeping. She doesn’t want to engage. She doesn’t want to wake up. To have this…later, at a time that she is more receptive or things like that. Having it as a tool that they can go to at any time, is very helpful.” (Physician)

Table 2.

Representative Health Care Professional Responses to Open-Ended Questions

| Subject Experience of Transplant Process |

| “and so there was some question at times about treatment, but then this threw dad, as it does for a lot of families, threw dad into a bit of a crisis of faith but not mom. Mom was steadfast in her faith, and so I think that there was some difference in coping in that way. Dad was saying why is God doing this to us? Mom was strong in her religious convictions and strong in her church supports, and so there were just all these differences in the part that they were playing in all of this, and so we worked a lot on the tangible things. “ (Social Worker) “It's a high stress environment. These parents are going through a lot. They probably think of something then forget it the next minute. Maybe night time is just the time they recall a question. But yes, I would say a lot of questions come at night in addition to the day time.” (Nurse) |

| Role of BMT Roadmap on interaction between patients, caregivers, and providers |

| “I would say maybe the one thing is on the labs. The CBC is really helpful. With that one patient that fixates on things, I’m not sure if having the electrolytes and LFTs there would really help her. Like I said, I only bring these things up if there is something abnormal that I’m doing something about. A lot of times these patients will have abnormalities, because of meds. Again, depending on the patient you mentioned, but sometimes you don’t want it to dwell on it too much. Sometimes when they fixate on it too much, it may not be as helpful. I am thinking, maybe, because a lot of the electrolytes are going to be messed up going through it. Perhaps include the mag and the potassium and then with the LFTs, I don’t know if I would necessarily include them all the time. Definitely the CBC is helpful, but I don’t know, again, there are some people that may be useful for it.” (Physician) “Yes. At least this way they could look and know who, and so— Oh, it was her. Oh, nice. Tha's really nice. These must be the pictures from that were up on the wall out there. Good. Tha's great. I like that. I like that a lot.” (Nurse Coordinator) “Again, the fact that they see this beside us, talking or them seeing it on the chart. The fact that they have this available to them. I remember that one particular patient that I had to redirect a lot also. She, for example, would be… Maybe not, during the times we were working. She is sleeping. She doesn’ want to engage. She doesn’t want to wake up. To have this, to be able to be a good tool, to have this later, at a time that she is more receptive or things like that. Having it as a tool that they can go to at any time, is very helpful.” (Physician) |

| Strengths and Weaknesses of BMT Roadmap |

| “No, I think the language is great, because I think i’s just middle of the road, right? I’s not like, oh, you feel yucky, but it’s also not complicated clinical language, so I think it sounds great, and I think one of the things that we had briefly discussed is talking about GVHD and any of these and choosing to allow families to access that information but not necessarily put it on page one where it would spear everybody, so this seems like a good… Yes.” (Social Worker) “I think being able to see the labs and see the green dots takes away some of the pressure from the parent who is here having to communicate that information, or the parent who is at home having to seek out that information if they just have it, because a lot of times (0:43:37.2 unclear) hurry up and wait, so if a family can, not really need much information but just take a look, go on here and sees whatever today, I think that could be really helpful. I think some of the glossary and the general idea of wha’s happening at this point, I think tha’s information that a lot of times, even though tha’s simple information, it’s a little bit harder to communicate what’s happening at the end of the day, and that could be really helpful too. I could imagine it being very useful in that situation, if both had access to it” (Social Worker) “I think a couple of things having hand dandy like right here. In the moment, they can look up their labs. It’s not dependent on the nurse bringing them their labs every day. They can look it up and they can be empowered to know, “Oh my child’s white count is this. ” The child’s hemoglobin is below 7. So they’re going to get a transfusion today,” or that might be a question they have for the staff. “I see my son’s is 6.9. Are you guys planning to do this?” I think that’s empowering for families.” (Advanced Practice Nurse) |

| Strategies to Improve BMT Roadmap |

|

“…maybe more information on more content, and I guess that’s not as important strictly in-patient for now. Maybe when it’s outpatient, having here’s a phone number or an email or the clinic phone number or something associated with folks, that would be a good thing, but it would be pretty easy to find for patients.” (Social Worker) “Perhaps there would be interfaces with Fitbit because some adults for example they love to brag about how much they walked. They can say, "Yesterday I walked two miles. Today I'm going to walk two point five." To have that capability where you can actually connect a Fitbit for those hardcore transplanters at least so they can keep track of those things.” (Physician) “Can you put a statement in there like, “We expect some electrolyte and LFTs variations, that could be normal, going through this process. Discuss with your physician?” (Physician) “I would actually advocate putting the name that we usually use. Nobody uses promethazine everybody says phentramin. You’ve got the generic name on the top, and the brand name in small letters, or for the families I would actually use the name that we use. We call it Ativan. Nobody uses the term Lorazepam. I would flip it around. Ativan generic name, lorazepam.” (Physician) “Yes, because I think that if you give this to people prior to admission, they know the importance of things when they come in because really, mouth care, daily hygiene, those are all things families can do which will help optimize their stay and help minimize extra days and infections and so many things that I think get overlooked, even by nursing staff. I think it would be nice to have that.” (Nurse Specialist) |

Roadmap Uses

Caregivers reported that the Laboratory module was the one they viewed the most (Table 2). They were able to access the results as soon as they became available: “Every morning at 5:30 AM I wake up and refresh this… tell me what the counts were. We live by counts…”

The initial intent of BMT Roadmap was for caregiver support of patient-centric data. Some caregivers commented that the Roadmap could be used by other caregiving individuals, even those not technically-savvy: “My uncle and aunt came to visit us yesterday. They’re older, so the fact that they could use this was really awesome…”

Roadmap Suggestions for Improvement

Caregivers provided feedback and suggestions for improving the tool such as making changes to the graphical display for better understanding of the data: “…when I look at Labs, and I’m new to the liver panel and all those, a little pop-up explanation of why do I need to care about creatinine would be awesome…”

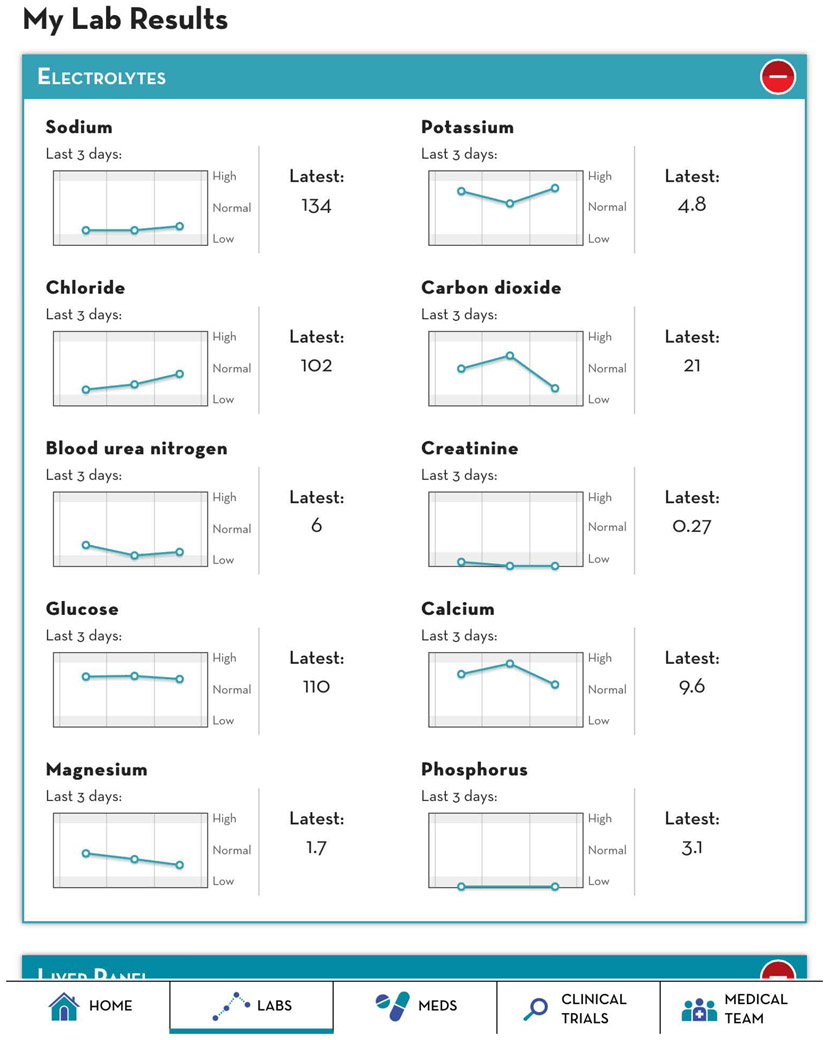

Caregivers focused primarily on the laboratory module and offered suggestions on the lay-out of the results. For example, users liked the graphical aspects of the laboratory results (Figure 1), but also wanted more control over how many days of data were shown on the graph: “I think we need more than the last three days. Because if her bilirubin is at 0.5 but I know two weeks ago it was at 3.0, I can be happy. I think longer-acting data…might actually tell a better story.”

Figure 1.

BMT Roadmap: Laboratory Results Module

While some caregivers and healthcare providers felt that reporting just the results were informative, other “information-seeking” caregivers preferred having more granular details other than just “high vs low,” such as “abnormal vs normal” next to their child’s laboratory result, although this was designed intentionally since the absolute numbers were not always reflective of an “abnormal” result: “…I would like to know what a normal range is. On his ALT or his red blood cells, it doesn’t give you what it should be.”

Caregivers also recommended additional modules related to communication of information as well as patient’s vital signs to be added to the tool: “The two things I’ve said before and I’ll say it again is that the vitals and the communication. If there’s some way to take notes to share with the doctor.”

Organization and Management

While interviews focused on use of BMT Roadmap by caregivers, a common theme throughout was their attention to how they organized and managed their childs’ healthcare, including use of calendar systems or other types of artifacts, and how these ideas could be built into a future iteration of BMT Roadmap: “I was very, very formal in the beginning, that I kept a binder that I three hole punched everything in. Then I filled up about six of them and said, ‘I can’t handle this anymore’…Now, I just have a calendar that I jot stuff down.”

Caregivers also described how they would “check-off” their caregiving duties through use of lists or charts. Some reported using their mobile devices to set alarms in reminding when a certain task needed to be completed: “Usually I have a notepad. I keep it in my calendar. Or I have a memo thing on my phone. If I’m out and about and I’m like, ‘Oh I need to ask them this, ’ I’ll type it in.”

In addition to organizing healthcare plans through direct communication with the provider team, some caregivers commented on using the internet for their source of information: “I Google. Yes, if I don’t find the answer I want or I’m still confused, then Ill go to his nurses or his doctors. But, Google always comes first because I want to know everything. I want to learn it all, and if you hold back on me…I want to know it all.”

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to utilize a patient-centered HIT tool specific to the inpatient BMT setting. Despite being a relatively heterogeneous population of caregivers, BMT Roadmap was well-received and considered a useful tool. The qualitative themes that emerged were notably similar to those reported by others of the long-term impact on caregivers of HCT survivors.2, 15 Caregivers suggested improvements for adding more information to the tool, including daily check lists for tasks such as walking and bathing as well being allowed to use the tool in the outpatient setting or upon readmission. In two caregivers, the patients were readmitted for second HCT and they specifically requested to have BMT Roadmap during their second hospitalization.

A common theme that emerged during the weekly, qualitative interviews was the critical importance of communication among patients, caregivers and the health care team. Participants felt BMT Roadmap augmented, rather than detracted, from this communication. The research team had initial concerns about the tool negatively impacting the workflow and experiences of the healthcare team. However, once implemented, they acknowledged that the tool was not burdensome and actually added to the care they provided patients. Healthcare providers noted that caregivers were less focused in their discussion on laboratory results or medications and appeared to be less anxious during rounds, which we attribute to ready-access of information in real-time.

Almost all caregivers expressed a desire to have as much information about the process as possible. These caregivers emphasized the need to create, maintain, and improvise various organization and management strategies to cope with the large volume of information that accompanies HCT. Given that caregivers were regularly turning to the internet for information, this HIT tool could serve as a source for well-vetted, caregiving resources. Participants regularly reflected on the emotional burden of the HCT process consistent with the literature;16 suggesting an important role for a user-centered tool such as BMT Roadmap in such stressful situations.

Effective interactions between patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers are known to impact clinical outcomes,17 and the finding from our study suggests that BMT Roadmap did indeed support interactions and communication. Patients who report good communication with their healthcare providers are more likely to be satisfied with their care, share pertinent information for accurate diagnosis of problems, follow treatment recommendations, and adhere to prescribed treatments.18, 19 In this study, patients and caregivers were eager to follow and track their own health information (particularly laboratory data which allows caregivers to track when “success” or engraftment of HCT takes place), in real-time or when convenient. The intent of BMT Roadmap was to inform, educate, and engage patients and their caretakers, facilitated by HIT, which is consistent with another recent finding on use of inpatient real-time health information to engage families in pediatric hospital care.20 While the study was conducted with parents of children hospitalized on a medical/surgical unit, majority of the parents reported improved healthcare team communication through the tablet device.

In summary, BMT Roadmap was developed with a multi-disciplinary team to address multiple information needs of caregivers undergoing HCT. Our qualitative study suggests that patient-centric HIT tools may be able to engage caregivers in hospital care. BMT Roadmap could meet this need, particularly in the HCT setting where complex, long-term communication and information recall is necessary for both patients and caregivers. To our knowledge, there are no other HIT applications in the market meeting this need and thus the findings herein are novel and of relevance. Nonetheless, we recognize the limitation of our small sample size and the single institution experience. We are expanding the current technology to an adult BMT population, and have included quantitative assessments to integrate the findings with our qualitative domains. It remains essential that evidence-based data with user-centered experiences are captured before widespread dissemination of such tools.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (R21HS023613 “Personalized Engagement Tool for Pediatric BMT Patients and Caregivers” to S.W.C.) and the A. Alfred Taubman Medical Research Institute. Sung Won Choi is the Edith Briskin / Shirly K. Schlafer Foundation Research Professor. This work was recently presented at the upcoming American Society of Hematology Meeting (December 2016). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the above mentioned parties. We would like to thank all the caregivers and healthcare providers who participated in this study.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedman CP, Wong AK, Blumenthal D. Achieving a nationwide learning health system. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:57cm29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop MM, Curbow BA, Springer SH, Lee JA, Wingard JR. Comparison of lasting life changes after cancer and bmt: Perspectives of long-term survivors and spouses. Psychooncology. 2011;20:926–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Von Ah D, Spath M, Nielsen A, Fife B. The caregiver's role across the bone marrow transplantation trajectory. Cancer nursing. 2016;39:E12–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaziunas E, Buyuktur A, Jones J, Choi S, Hanauer D, Ackerman M. Transition and reflection in the use of health information: The case of pediatric bone marrow transplant caregivers. Proceedings of the acm 2015 conference on computer supported cooperative work (cscw '15) Vancouver, british columbia, canada. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaziunas E, Hanauer DA, Ackerman MS, Choi SW. Identifying unmet informational needs in the inpatient setting to increase patient and caregiver engagement in the context of pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maher M, Kaziunas E, Ackerman M, Derry H, Forringer R, Miller K, O'Reilly D, An LC, Tewari M, Hanauer DA, Choi SW. User-centered design groups to engage patients and caregivers with a personalized health information technology tool. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016;22:349–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maher M, Hanauer DA, Kaziunas E, Ackerman MS, Derry H, Forringer R, Miller K, O'Reilly D, An L, Tewari M, Choi SW. A novel health information technology communication system to increase caregiver activation in the context of hospital-based pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation: A pilot study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4:e119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keusch F, Rao R, Chang L, Lepkowski J, Reddy P, Choi SW. Participation in clinical research: Perspectives of adult patients and parents of pediatric patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2014;20:1604–1611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Büyüktür AG, Ackerman MS. Issues and opportunities in transitions from speciality care: A field study of bone marrow transplant. Behaviour & Information Technology. 2014:1–19 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piette JD, Valenstein M, Eisenber D, Fetters MD, Sen A, Saunders D, Watkins D, Aikens JE. Rationale and methods of a trial to evaluate a depression telemonitoring program that includes a patient-selected support person. Journal of clinical trials 2014; 5:1 (protocol). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano-Clark VL, Smith KC. Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. 2011. Http://obssr.Od.Nih.Gov/mixed_methods_research. Last accessed on september 2, 2015.

- 12.Complex interventions in health: An overview of research methods. Edited by Richards david a. and hallberg ingalill rahm. 1st edition. Routledge taylor & francis group, london and new york. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miles AB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. Second edition. Thousand oaks, ca: Sage publications, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krippendorff K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Newbury park, ca: Sage publications; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bishop MM, Beaumont JL, Hahn EA, Cella D, Andrykowski MA, Brady MJ, Horowitz MM, Sobocinski KA, Rizzo JD, Wingard JR. Late effects of cancer and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation on spouses or partners compared with survivors and survivor-matched controls. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1403–1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barata A, Wood WA, Choi SW, Jim HS. Unmet needs for psychosocial care in hematologic malignancies and hematopoietic cell transplant. Current hematologic malignancy reports. 2016;11:280–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gentles SJ, Lokker C, McKibbon KA. Health information technology to facilitate communication involving health care providers, caregivers, and pediatric patients: A scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epstein RM, Street RLJ. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: Promoting healing and reducing suffering. 2007

- 19.Street RL Jr., Mazor KM, Arora NK. Assessing patient-centered communication in cancer care: Measures for surveillance of communication outcomes. J Oncol Pract. 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly MM, Hoonakker PL, Dean SM. Using an inpatient portal to engage families in pediatric hospital care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.