Abstract

Background:

Heart rate recovery (HRR) has been observed to be a significant prognostic measure in patients with heart failure (HF). However, the prognostic value of HRR has not been examined in regard to the level of patient effort during exercise testing. Using the peak respiratory exchange ratio (RER) and a large multicenter HF database we examined the prognostic utility of HRR.

Methods:

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPX) was performed in 806 HF patients who then underwent an active cool-down of at least 1 min. Peak oxygen consumption (VO2), ventilatory efficiency (VE/VCO2 slope), and peak RER were determined with subjects categorized into subgroups according to peak RER (<1.00, 1.00–1.09, ≥1.10). HRR was defined as the difference between heart rate at peak exercise and 1 min following test termination. Patients were followed for major cardiac events for up to four years post-CPX.

Results:

There were 163 major cardiac events (115 deaths, 20 left ventricular assist device implantations, and 28 transplantations) during the four year tracking period. Univariate Cox regression analysis results identified HRR as a significant (p<0.05) univariate predictor of adverse events regardless of the RER achieved. Multivariate Cox regression analysis in the overall group revealed that the VE/VCO2 slope was the strongest predictor of adverse events (chi-square: 110.9, p<0.001) with both HRR (residual chi-square: 16.7, p<0.001) and peak VO2 (residual chi-square: 10.4, p<0.01) adding significant prognostic value.

Conclusions:

HRR after symptom-limited exercise testing performed at sub-maximal efforts using RER to categorize level of effort is as predictive as HRR after maximal effort in HF patients.

Keywords: Heart failure, Heart rate recovery, Respiratory exchange ratio

1. Introduction

The recovery heart rate response after a graded exercise test, traditionally termed heart rate recovery (HRR), has long been a variable of interest with potential value in the clinical setting [1–11]. Specifically, the capacity of the heart rate to decelerate in recovery reflects parasympathetic reactivation and provides a unique perspective regarding fitness and health. Consistently, a low value for HRR has been applied as a marker of increased mortality [1–11].

Two large studies have convincingly identified HRR≤/>12 beats at 1 min post symptom-limited exercise as the demarcation point that predicts increased mortality [12,13]. Two other large studies employed sub-maximal exercise testing (terminating exercise at 85–90% of age-predicted peak heart rate) and found that abnormal HRR retained its efficacy as a prognostic index, independent of the peak heart rate (HR) achieved in relation to age-predicted values [14,15]. While the sensitivity of HRR to assess prognostic risk in relation to sub-maximal intensity runs contrary to the common assumption that high exertion exercise increases diagnostic sensitivity, several recent investigations have raised questions regarding peak HR to gauge physiologic effort [16,17]. Thus, the impact of exertion on HRR may be better assessed by other measures of exercise intensity. Given the common confounding effects of beta-blockers and chronotropic incompetence in the HF population, a better understanding and methodological refinement of exercise intensity on HRR remains important to clarify. Therefore, further work is needed to confirm whether HRR retains prognostic value irrespective of exercise effort.

A readily obtainable variable during cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPX), the peak respiratory exchange ratio (RER), is a more precise method for gauging subject effort during exercise [18–22]. A peak RER≥1.10 is widely accepted as a true indication of maximal effort [18–22]. Thus, a peak RER<1.10 has been associated with a sub-maximal exercise effort in both healthy persons and persons with HF [18–22]. Using data from a large multicenter HF CPX database, we examined the prognostic utility of HRR according to peak RER achieved in order to better determine the influence of exertional effort on this prognostic marker.

2. Methods

This study was a multi-center analysis including HF patients from the exercise testing laboratories at San Paolo Hospital, Milan, Italy; LeBauer Cardiovascular Research Foundation, Greensboro, North Carolina, USA; Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, USA; VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, California, USA; Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA and Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, USA. A total of 806 patients with systolic HF were included in the analysis. The inclusion criteria consisted of a diagnosis of HF and evidence of left ventricular systolic dysfunction by two-dimensional echocardiography obtained within one month of data collection. All subjects completed a written informed consent and institutional review board approval was obtained at each institution. The authors of this manuscript have certified that they comply with the Principles of Ethical Publishing in the International Journal of Cardiology.

2.1. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPX) procedures

Symptom-limited CPX was performed on all subjects and pharmacologic therapy was maintained during exercise testing. Progressive exercise testing protocols on bicycles and/or treadmills were employed at all centers and ventilatory expired gas analysis was performed using a metabolic cart (Medgraphics CPX-D and Ultima, Minneapolis, MN, Sensormedics Vmax29, Yorba Linda, CA or Parvomedics TrueOne 2400, Sandy, UT). Before each test, the equipment was calibrated in standard fashion using reference gases. Heart rate was determined at rest, peak exercise and at one minute recovery. The percent-predicted maximal HR achieved was determined by the following equation: [peak HR/(220−age)]×100. Heart rate recovery was defined as the difference between peak HR and HR 1 min following test termination. All centers followed an active cool-down protocol of at least 1 min. In addition, minute ventilation (VE), oxygen uptake (VO2), and carbon dioxide output (VCO2) were acquired breath-by-breath, and averaged over 10-second intervals. Peak VO2 and peak respiratory exchange ratio (RER) were expressed as the highest 10-second averaged sample obtained during the last 20 s of testing. VE and VCO2 values, acquired from the initiation of exercise to peak, were input into spreadsheet software (Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Corp., Bellevue, WA) to calculate the VE/VCO2 slope via least squares linear regression (y=mx+b, m=slope). Subjects were categorized into subgroups according to peak RER: <1.00, 1.00–1.09, ≥1.10.

2.2. Endpoints

In the overall cohort, subjects were followed for major cardiac events (mortality, LVAD implantation, urgent heart transplantation) via medical chart review for up to four years post CPX. Subjects were followed by the HF programs at their respective institution providing a high likelihood that all events were captured. External means of tracking events, such as the Social Security Death Index, were not utilized in the present study. Any death with a cardiac-related discharge diagnosis was considered an event.

2.3. Statistical analysis

A statistical software package (SPSS 19.0, Chicago, IL) was used to perform all analyses. Continuous and categorical data are reported as mean±standard deviation and percentages, respectively. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) assessed differences in baseline and CPX variables between subgroups of subjects according to peak RER level. The Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference test was used for post-ANOVA pairwise comparisons. Differences in categorical data were assessed by chi-square analysis. Univariate Cox regression analysis was used to assess the prognostic value of HRR in the overall group and within each peak RER subgroup. Hazard ratios were also determined for the overall group and each subgroup according to the established dichotomous classification of HRR (≤/>12 beats) [11–13]. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to assess the differences in survival among subjects according to dichotomous classification of HRR. The log-rank test determined statistical significance among the HRR categories for the Kaplan-Meier analyses. Multivariate (forward stepwise method; entry and removal values of 0.05 and 0.10, respectively) Cox regression analysis was used to assess the prognostic value of HRR in addition to other key CPX variables in the overall group. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

3. Results

There were 163 major cardiac events (115 deaths, 20 left ventricular assist device implantations and 28 transplantations) during the four year tracking period in the entire group. The average yearly event rate was 9.4%. The number of events for subjects with a peak RER of <1.00, 1.00–1.09 and ≥1.10 was 29, 46 and 88, respectively. As shown in Table 1 the mean LVEF, peak VO2, peak HR, percentage of the age-predicted maximal HR achieved, and HRR were significantly lower in subjects experiencing a major cardiac event. Subjects experiencing a major cardiac event were also observed to have a significantly greater resting HR and VE/VCO2 slope.

Table 1.

Differences in patient characteristics and CPX variables according to major cardiac event status.

| Event-free (n = 643) | Major cardiac event (n = 163) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.5±13.1 | 56.6±12.7 | 0.34 |

| Gender (% male) | 73.6 | 76.7 | 0.48 |

| HF etiology (% ischemic/non-ischemic) | 40/60 | 49/51 | 0.02 |

| LVEF (%) | 29.2±9.8 | 23.4±9.0 | <0.001 |

| Prescribed beta-blocker (%) | 78 | 71 | 0.06 |

| Prescribed ACE inhibitor (%) | 75 | 67 | 0.04 |

| Resting HR (beats/min) | 74.0±13.0 | 76.6±15.3 | 0.04 |

| Peak HR (beats/min) | 129.2±23.8 | 117.5±21.8 | <0.001 |

| Percent-predicted maximal HR achieved (%) | 78.7±13.9 | 71.9±12.4 | <0.001 |

| HRR | 18.9±11.5 | 12.6±10.2 | <0.001 |

| Peak RER | 1.11±0.14 | 1.13±0.16 | 0.21 |

| PeakVO2 (ml O2-kg−1-min−1) | 16.3 ± 5.4 | 13.1±4.2 | <0.001 |

| VE/VCO2 slope | 33.6±8.3 | 40.2±10.2 | <0.001 |

HF=heart failure; LVEF=left ventricular ejection fraction; ACE=angiotensin converting enzyme; HR=heart rate; HRR=heart rate recovery; RER=respiratory exchange ratio; VO2=oxygen consumption; VE/VCO2=minute ventilation/carbon dioxide production.

Table 2 lists the key baseline and CPX characteristics in the overall group and peak RER subgroups. Several differences were apparent according to RER grouping, including age, HF etiology, beta-blocker use, resting HR, HRR, peak VO2 and, as expected, peak RER.

Table 2.

Differences in key baseline and CPX variables in the overall group and peak RER subgroups.

| Overall group (n = 806) | HRR: peakRER<1.00 (n = 149) | HRR: peak RER 1.00–1.09 (n = 214) | HRR: peakRER≥ 1.10 (n = 443) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 55.7±13.0 | 58.6±11.4 | 56.8±14.2 | 54.2±12.8 |

| Gender (% male) | 74 | 72 | 75 | 74 |

| HF etiology (% ischemic/non-ischemic)b | 42/58 | 48/52 | 46/54 | 37/63 |

| LVEF (%) | 28.0±9.9 | 28.9±10.4 | 28.0±9.7 | 27.3±9.7 |

| Prescribed beta-blocker (%)c | 76 | 65 | 72 | 82 |

| Prescribed ACE inhibitor (%) | 73 | 72 | 72 | 74 |

| Resting HR (beats/min)d | 74.6±13.6 | 74.3±12.8 | 76.7±14.1 | 73.6±13.4 |

| Peak HR (beats/min) | 126.9±23.8 | 124.3±21.6 | 126.7±22.0 | 127.8±25.3 |

| Percent-predicted maximal HR achieved (%) | 77.3±13.9 | 77.2±13.6 | 77.8±12.9 | 77.1 ±14.6 |

| HRRe | 17.6±11.5 | 16.1 ±7.1 | 16.0±9.5 | 18.9±13.3 |

| Peak RERf | 1.11 ±0.14 | 0.92±0.05 | 1.05±0.03 | 1.21 ±0.10 |

| Peak VO2 (ml O2-kg−1-min−1)g | 15.6±5.4 | 14.7 ± 4.6 | 15.5±5.6 | 16.0±5.4 |

| VE/VCO2 slope | 35.0±9.1 | 35.9±9.6 | 35.8±9.5 | 34.3±8.8 |

HRR=heart rate recovery; RER=respiratory exchange ratio; HF=heart failure; ACE=angiotensin converting enzyme; HR=heart rate; VO2=oxygen consumption; VE/VCO2= minute ventilation/carbon dioxide production.

Peak RER≥1.10 subgroup significantly lower than the other two subgroups, p<0.05.

Peak RER≥1.10 subgroup significantly different from the other two subgroups, p<0.01.

All three subgroups significantly different, p<0.05.

Peak RER 1.00–1.09 subgroup significantly higher than the peak RER≥1.10 subgroup, p<0.05.

Peak RER≥1.10 subgroup significantly higher than the other two subgroups, p<0.05.

All three subgroups significantly different, p<0.001.

Peak RER≥1.10 subgroup significantly higher than the peak RER<1.00 subgroup, p<0.05.

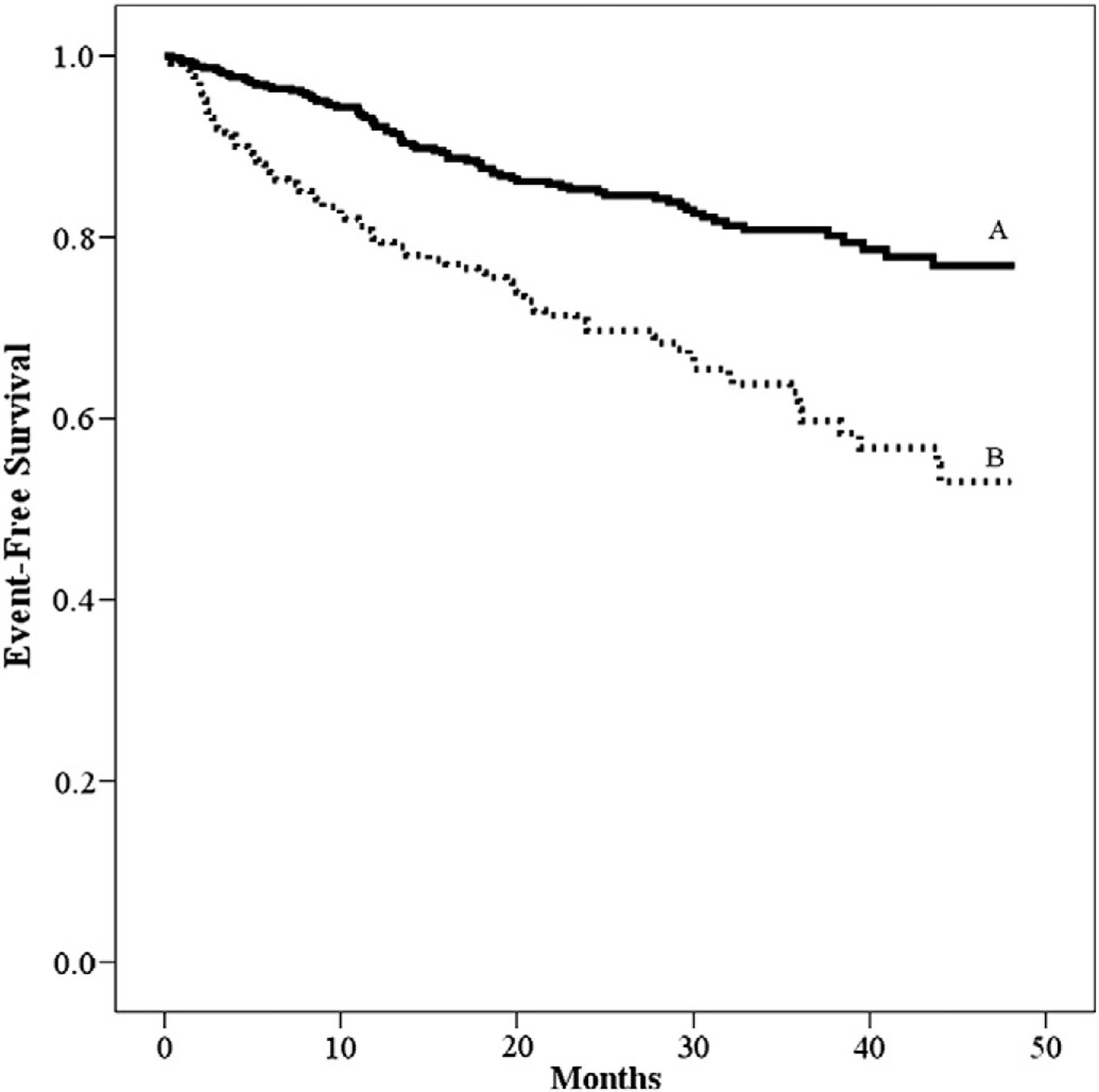

Univariate Cox regression analysis results for HRR are listed in Table 3. In the overall group and all peak RER subgroups, HRR was a significant univariate predictor of adverse events. Moreover, the most frequently cited threshold value for HRR at 1 min (≤/>12 beats) was prognostically significant in all scenarios. Furthermore, HRR remained a significant predictor of adverse events with similar predictive power when adjusted for key patient characteristics in the overall group and all peak RER subgroups except for the peak RER ≥1.10 subgroup with HRR dichotomized. Kaplan-Meier analysis for the HRR threshold of ≤/>12 beats in the overall group is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses for HRR in the overall group and peak RER subgroups.

| HRR as continuous variable | HRR as dichotomous variable (≤/>12 beats) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-square | Hazard ratio & adjusted hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | Hazard ratio & adjusted hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | |

| Overall group (163 events) | 35.9 | 0.95 (0.94–0.97)*** | 2.4 (1.7–3.4)*** |

| 0.97 (0.95–0.98)** | 1.6 (1.2–2.2)** | ||

| Peak RER< 1.00 subgroup (29 events) | 12.8 | 0.93 (0.89–0.97)*** | 4.1 (2.0–8.6)*** |

| 0.92 (0.88–0.96)** | 4.2 (2.0–8.8)*** | ||

| Peak RER 1.00–1.09 subgroup (46 events) | 9.1 | 0.95 (0.91–0.98)** | 2.3 (1.3–4.0)** |

| 0.95 (0.91–0.98)** | 2.1 (1.1–3.7)* | ||

| Peak RER> 1.10 subgroup (88 events) | 19.0 | 0.96 (0.94–0.98)** | 2.0 (1.3–3.1)** |

| 0.98 (0.96–1.00)* | - | ||

Multivariate Cox regression was performed to obtain the adjusted hazard ratio to examine HRR in relation to other patient characteristics and CPX results. The number of predictor variables included in each model was different because the number of events in each RER subgroup was different. Variables in each model included: overall group (age, heart failure etiology, beta-blocker use, LVEF, resting heart rate, peak VO2, VE/VCO2 slope, and HRR), peak RER<1.0 (peak VO2, VE/VCO2 slope, and HRR), peak RER 1.0–1.09 (LVEF, peak VO2, VE/VCO2 slope, and HRR), peak RER≥1.10 (age, heart failure etiology, beta-blocker use, LVEF, resting heart rate, peak VO2, VE/VCO2 slope, and HRR).

p<0.05.

p<0.01.

p<0.001.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis for HRR.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis in the overall group revealed that the VE/VCO2 slope was the strongest predictor of adverse events (chi-square: 109.5, p<0.001) (Table 4). Additional significant predictors of adverse events in the overall group included LVEF, HRR, peak VO2, and beta-blocker treatment. HRR was a significant predictor of adverse events in all peak RER subgroups as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis for key patient characteristics and CPX variables in the overall group and peak RER subgroups.

| Overall group | ||

|---|---|---|

| Chi-square | p-Value | |

| VE/VCO2 slope | 109.50 | <0.001 |

| Residual chi-square | ||

| LVEF | 24.03 | <0.001 |

| HRR** | 12.49 | 0.001 |

| Peak VO2 | 9.17 | <0.01 |

| Beta-blockade | 5.09 | 0.02 |

| Peak RER < 1.00 | ||

| Chi-square | ||

| HRR** | 12.82 | <0.001 |

| Residual chi-square | ||

| VE/VCO2 slope | 9.43 | 0.001 |

| Peak RER 1.00–1.09 | ||

| Chi-square | ||

| VE/VCO2 slope | 13.20 | <0.001 |

| Residual chi-square | ||

| HRR** | 9.31 | <0.01 |

| Peak RER ≥ 1.10 | ||

| Chi-square | ||

| VE/VCO2 slope | 98.88 | <0.001 |

| LVEF | Residual chi-square 12.42 | 0.001 |

| Peak VO2 | 4.74 | 0.03 |

| Beta-blockade | 6.24 | <0.01 |

| HRR** | 4.35 | 0.04 |

CPX=cardiopulmonary exercise testing; VE/VCO2=minute ventilation/carbon dioxide production; LVEF=left ventricular ejection fraction; HRR**=heart rate recovery as a continuous variable; VO2=oxygen consumption.

Only variables retained in models are presented; the number of variables included in each model was different due to the number of events in each RER subgroup. Variables in each model included: overall group (age, heart failure etiology, beta-blocker use, LVEF, resting heart rate, peak VO2, VE/VCO2 slope, and HRR), peak RER<1.0 (peak VO2, VE/VCO2 slope, and HRR), peak RER 1.0–1.09 (LVEF, peak VO2, VE/VCO2 slope, and HRR), and peak RER≥1.10 (age, heart failure etiology, beta-blocker use, LVEF, resting heart rate, peak VO2, VE/VCO2 slope, and HRR).

4. Discussion

HRR after maximal and sub-maximal exercise efforts has been found to be an important predictor of survival in apparently healthy persons [12–15,23] as well as in patients with heart disease regardless of age, gender, exercise capacity, left ventricular systolic function, and presence or absence of myocardial ischemia [24]. Furthermore, HRR has been found to be an important predictor of survival in patients with HF irrespective of beta-blockade [25–29]. The current study is the first to our knowledge to identify that the prognostic significance of HRR is not dependent on a common, objective indicator of maximal effort in patients with HF. We have shown that HRR after sub-maximal efforts, defined by peak RER, is as predictive as HRR after maximal effort in patients with HF. Consistently, our analysis corroborates prior studies that showed prognostic utility of HRR irrespective of peak HR [14,15].

Peak RER has long been accepted as an objective marker to distinguish maximal from sub-maximal effort [18–22] and in the current study it was used to categorize two levels of sub-maximal exercise (RER<1.00 and 1.00–1.09); outcomes in these two groups were compared with those among patients achieving maximal exercise (RER≥1.10). Although the exercise tests employed in the current study were symptom-limited, the peak RER achieved during testing provides a valid reflection of true physiologic exertion [18–22]. The RER achieved from sub-maximal exercise tests previously performed in apparently healthy subjects was not reported, but it is likely that they were in the range of 0.90–1.05 in view of other reported exercise test studies [14,15,19–22]. The mean metabolic equivalents (METS) achieved in the sub-maximal exercise tests reported by Cole et al. was approximately 10 METS with an average exercise test duration of 10 min during the Bruce or modified Bruce protocol [14]. The exercise characteristics reported by Morshedi-Meibodi et al. for men and women included a mean exercise duration of 10.5 and 8.3 min, respectively, and a mean peak heart rate of 166 beats/min for both men and women (with 80% of men and 77% of women achieving 85% of the age- and gender-predicted maximal heart rates) during standard Bruce treadmill testing [15]. In our study, 45% of the patients performed sub-maximal exercise efforts (RER<1.10) during treadmill or cycle ergometry testing with a peak heart rate of approximately 125 beats/min (achieving 77% of the age- and gender-predicted maximal heart rates).

The recovery procedures employed in studies that have examined HRR in apparently healthy individuals or persons with heart disease vary, with some studies using an active recovery for approximately 1 min after exercise and others stopping exercise immediately [12–15,23–30]. The body position in which patients were placed after exercise has also varied among studies, with some placing patients supine and others having patients sit during recovery [12–15,23–30]. In the current study, subjects underwent an active recovery at a workload equivalent to the initial exercise stage (≈2 METs) for at least 1 min. This approach to the recovery period is consistent with current practice patterns in most exercise testing laboratories making our findings highly applicable to HF patients undergoing CPX in the clinical setting. Specifically, HRR should be considered a key CPX variable for prognostic purposes irrespective of peak RER.

A variety of different definitions of HRR have been used in many of the aforementioned studies which likely accounts for some of the observed differences in study results [12–15,23–30]. However, although two previous sub-maximal exercise testing studies defined an abnormal HRR as a change from the peak heart rate to minute two of recovery of 42 beats or less [14,15], Morshedi-Meibodi et al. also examined an abnormal HRR at minute one of recovery which was defined as a change from the peak heart rate of 12 beats or less [15]. In the latter study, an abnormal HRR at minute one of recovery was also found to be predictive of cardiovascular event risk in univariate models [15]. Based on the available literature, Huang et al. have suggested that a one minute HRR value of 12 beats is likely to improve the specificity and positive predictive value for mortality and cardiovascular events [10,11]. While the majority of studies have focused on patients with coronary artery disease, Driss et al. also suggested that the optimal one minute HRR threshold is 12 beats in patients with HF [27]. Although a variety of optimal one minute HRR threshold values have been reported (from 6.5 to 17 beats) [25–29], we chose to use a one minute cutoff HRR of 12 beats in order to be consistent with the above studies.

The results of the current study are similar to previous studies in apparently healthy individuals and in persons with HF [12–15,23–29]. In particular, our analysis of HRR as a dichotomous variable for the overall group produced a hazard ratio of 2.4, which is similar to those reported in previous studies. The hazard ratio was significant at all levels of effort, but was greatest for patients with the lowest RER (4.1; CI=2.0–8.6) and least for patients with the highest RER (2.0; CI=1.3–3.1). The hazard ratio for patients with an RER between 1.0 and 1.9 was 2.3 (CI=1.3–4.0). The reasons for these differences between groups are unclear, but may be related to patients in the RER<1.0 subgroup being significantly older, having a lower peak VO2, having a greater percentage of patients with ischemic HF, and having a smaller percentage of patients prescribed a beta-blocker than the RER≥1.10 subgroup. However, there were no significant differences in patient characteristics between the RER<1.0 and RER 1.0–1.09 subgroups. In addition, there was no significant difference in peak HR among the RER subgroups with the percent-predicted maximal HR achieved being identical (77%) in all three RER subgroups.

Despite our finding that the VE/VCO2 slope was the strongest predictor of adverse events in the multivariate model in the overall group, HRR along with peak VO2 added significant prognostic value. These results are important and highlight the manner by which HRR represents a unique facet (i.e. autonomic tone) of fitness and health [1–11]. Furthermore, recent findings among patients with heart disease participating in cardiac rehabilitation revealed that HRR improved after 12 weeks of rehabilitation and was associated with improved survival [31]. In fact, 41% of patients with an abnormal baseline HRR (defined as <12 beats/min at minute one of recovery) normalized HRR following training (increasing significantly from a mean of 6.5±4.1 at baseline to 11.5±6.8 beats/min) [31]. In a multivariate model, failure to normalize HRR was significantly associated with older age, lack of improvement in exercise capacity, peripheral arterial disease, and prior HF. Finally, failure to normalize HRR after cardiac rehabilitation predicted a higher mortality [31].

The above results and other studies of HRR in patients with HF have utilized symptom limited exercise tests; no previous study to our knowledge has examined the effects of exercise effort on the prognostic value of HRR [24–31]. We have observed that the prognostic significance of HRR is not dependent on maximal effort in patients with HF. In view of this, the recommendation by Mezzani et al. to exercise patients with HF as close as possible to a RER of 1.15 may be unnecessary when examining HRR for prognostic purposes [32]. Mezzani et al. found that patients with HF who had a peak VO2≤10 ml O2·kg−1·min−1 and a peak RER≥1.15 had a poorer 2-year survival rate than patients with a peak VO2≤10 ml O2·kg−1·min−1 and a peak RER<1.15 [32]. Although the relatively small number of patients studied by Mezzani et al. were older and had poorer exercise tolerance, there was no significant difference in peak RER between patients with a peak VO2≤10 ml O2·kg−1·min−1 and peak VO2>10, but ≤14 ml O2·kg−1·min−1 [32]. Clearly, the examination of HRR combined with peak VO2 and the VE/VCO2 slope has prognostic relevance as demonstrated in our data. Continued prognostic modeling in patients with HF is warranted to optimize utilization of CPX data for clinical assessment.

The finding that HRR during sub-maximal exercise is predictive of survival in patients with HF is important and highlights the ease by which this simple measure may be employed in future studies and clinical practice if similar prognostic information is observed. In fact, it seems plausible that HRR could be examined after not only sub-maximal exercise testing, but possibly after a 6-minute walk test (6MWT). Although the 6MWT is recommended as a functional performance measure in patients with HF and is commonly administered [18,33], only one study has examined HRR following this procedure [34]. In a small group of patients with HF who were awaiting cardiac transplantation, HRR at minute-two of recovery was observed to be significantly lower in patients who died or underwent cardiac transplantation compared to patients surviving and not receiving cardiac transplantation [34]. One additional study of HRR using the 6MWT in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis found that abnormal HRR (defined as <13 beats at minute one and 22 beats at minute two of recovery) was associated with poorer survival [35]. In the latter study, abnormal HRR at 1 min of recovery was the most significant predictor of mortality with a hazard ratio of 5.2 (CI=1.8–15.2) [35]. In addition, a significant relationship (r=0.44; p<0.0001) was observed between the 6MWT distance ambulated and HRR at 1 min of recovery [35]. In view of these findings and the findings from the current study, future investigation of HRR after the 6MWT is needed.

In view of the overall prognostic value of HRR and the potential for improved HRR from cardiac rehabilitation and sildenafil therapy in patients with heart disease and HF, respectively [31,36], routine assessment of HRR during submaximal and maximal exercise assessments is warranted. Although no consensus has been reached on the best methods and definitions for HRR, the methods by which HRR may be best employed and understood have been presented with the suggestion that HRR become a routine supplement to CPX since it compares similarly in prognostic power to age and metabolic equivalents [37]. Future investigation of HRR in patients with HF undergoing therapeutic interventions is needed as is the investigation of optimal methods and definitions to measure HRR.

Several potential limitations to this study exist and include the retrospective nature of the study as well as the acquisition of data from several different centers. Although the current study is retrospective, the majority of large studies examining HRR after exercise have also been retrospective [12–15]. The acquisition of data from several different centers is a potential limitation, but standardized CPX methods employed at each of the centers decreased such potential and included the use of progressive exercise testing protocols and active cool-down protocols for at least 1 min. The use of both bicycle CPX and treadmill CPX may be a potential limitation, but other studies have examined HRR after bicycle exercise and have found results similar to studies in which treadmill CPX was employed [1,4]. Furthermore, rather than a limitation, the findings in the current study expand the use of different modes of exercise to examine HRR. However, investigation of potential confounding issues that may limit the clinical utility of HRR is worthy of further investigation.

In summary, HRR after symptom-limited CPX performed at sub-maximal efforts as defined by peak RER is as predictive as HRR after maximal effort in patients with HF. Further examination of HRR after sub-maximal exercise assessments is warranted.

References

- [1].Imai K, Sato H, Hori M, et al. Vagally mediated heart rate recovery after exercise is accelerated in athletes but blunted in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;24:1529–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pierpont GL, Voth EJ. Assessing autonomic function by analysis of heart rate recovery from exercise in healthy subjects. Am J Cardiol 2004;94(1):64–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ng J, Sundaram S, Kadish AH, Goldberger JJ. Autonomic effects on the spectral analysis of heart rate variability after exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009;297:H1421–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jehn M, Halle M, Schuster T, Hanssen H, Koehler F, Schmidt-Trucksass A. Multivariable analysis of heart rate recovery after cycle ergometry in heart failure: exercise in heart failure. Heart Lung 2011;40:E129–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Goldsmith RL, Bloomfield DM, Rosenwinkel ET. Exercise and autonomic function. Coron Artery Dis 2000;11:129–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sleight P, La Rovere MT, Mortara A, et al. Physiology and pathophysiology of heart rate and blood pressure variability in humans: is power spectral analysis largely an index of baroreflex gain? Clin Sci (Lond) 1995;88:103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Convertino VA, Adams WC. Enhanced vagal baroreflex response during 24 h after acute exercise. Am J Physiol 1991;260(pt 2):R570–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kingwell BA, Dart AM, Jennings GL, Korner PI. Exercise training reduces the sympathetic component of the blood pressure-heart rate baroreflex in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 1992;82:357–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fisher JP, Seifert T, Hartwich D, Young CN, Secher NH, Fadel PJ. Autonomic control of heart rate by metabolically sensitive skeletal muscle afferents in humans. J Physiol 2010;588(7):1117–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Huang PH, Leu HB, Chen JW, et al. Usefulness of attenuated heart rate recovery immediately after exercise to predict endothelial dysfunction in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 2004;93:10–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Huang PH, Leu HB, Chen JW, Lin SJ. Heart rate recovery after exercise and endothelial function — two important factors to predict cardiovascular events. Prev Cardiol 2005;8:167–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cole CR, Blackstone EH, Pashkow FJ, Snader CE, Lauer MS. Heart-rate recovery immediately after exercise as a predictor of mortality. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1351–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nishime EO, Cole CR, Blackstone EH, Pashkow FJ, Lauer MS. Heart rate recovery and treadmill exercise score as predictors of mortality in patients referred for exercise ECG. JAMA 2000;284:1392–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cole CR, Foody JM, Blackstone EH, Lauer MS. Heart rate recovery after submaximal exercise testing as a predictor of mortality in a cardiovascular healthy cohort. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:552–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Morshedi-Meibodi A, Larson MG, Levy D, O’Donnell CJ, Vasan RS. Heart rate recovery after treadmill exercise testing and risk of cardiovascular disease events (The Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 2002;90:848–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jain M, Nkonde C, Lin B, Walker A, Wackers F. 85% of maximal age-predicted heart rate is not a valid endpoint for exercise treadmill testing. J Nucl Cardiol 2011;18: 1026–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pinkstaff S, Peberdy MA, Kontos MC, Finucane S, Arena R. Quantifying exertion level during exercise stress testing using percentage of age-predicted maximal heart rate, rate pressure product, and perceived exertion. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85: 1095–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fleg JL, Pina IL, Balady GJ, et al. Assessment of functional capacity in clinical and research applications. Circulation 2000;102:1591–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Davies JA. Direct determination of aerobic power In: Maud PJ, Foster C, editors. Physiological assessment of human fitness. Champaign (Ill): Human Kinetics; 1995. p. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Froelicher VF, Myers JN, editors. Exercise and the heart Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Balady GJ, Berra KA, Golding LA, et al. Interpretation of clinical test data In: Franklin BA, Whaley MH, Howley ET, editors. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. p. 115–33. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wasserman K, Hansen J, Sue D, Casaburi R, Whipp B. Principles of exercise testing and interpretation. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Adabag AS, Grandits GA, Prineas RJ, Crow RS, Bloomfield HE, Neaton JD. Relation of heart rate parameters during exercise test to sudden death and all-cause mortality in asymptomatic men. Am J Cardiol 2008;101:1437–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Watanabe J, Thamilarasan M, Blackstone EH, Thomas JD, Lauer MS. Heart rate recovery immediately after treadmill exercise and left ventricular systolic dysfunction as predictors of mortality: the case of stress echocardiography. Circulation 2001;104:1911–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lipinski MJ, Vetrovec GW, Gorelik D, Froelicher VF. The importance of heart rate recovery in patients with heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Card Fail 2005;11(8):624–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Arena R, Guazzi M, Myers J, Peberdy MA. Prognostic value of heart rate recovery in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J 2006;151(4):851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Driss AB, Tabet JY, Meurin P, et al. Heart rate recovery identifies high risk heart failure patients with intermediate peak oxygen consumption values. Int J Cardiol 2011;149(2):284–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Arena R, Myers J, Abella J, et al. The prognostic value of the heart rate response during exercise and recovery in patients with heart failure: influence of beta-blockade. Int J Cardiol 2010;138:166–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Guazzi M, Myers J, Peberdy MA, Bensimhon D, Chase P, Arena R. Heart rate recovery predicts sudden cardiac death in heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2010;144(1):121–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Thomas DE, Exton SA, Yousef ZR. Heart rate deceleration after exercise predicts patients most likely to respond to cardiac resynchronization therapy. Heart 2010;96:1385–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jolly MA, Brennan DM, Cho L. Impact of exercise on heart rate recovery. Circulation 2011;124:1520–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Mezzani A, Corra V, Bosimini E, Giordano A, Giannuzzi P. Contribution of peak respiratory exchange ratio to peak VO2 prognostic reliability in patients with chronic heart failure and severely reduced exercise capacity. Am Heart J 2003;145:1102–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Radford MJ, Arnold JM, Bennett SJ, et al. ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with chronic heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Heart Failure Clinical Data Standards): developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation September 20 2005;112(12):1888–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cipriano G, Yuri D, Bernardelli GF, Mair V, Buffolo E, Branco JNR. Analysis of 6-minute walk test safety in pre-heart transplantation patients. Arq Bras Cardiol 2009;92(4): 294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Swigris JJ, Swick J, Wamboldt FS, et al. Heart rate recovery after 6-min walk test predicts survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2009;136:841–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Guazzi M, Arena R, Pinkstaff S, Guazzi MD. Six months of sildenafil therapy improves heart rate recovery in patients with heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2009;136: 341–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Shetler K, Marcus R, Froelicher VF, et al. Heart rate recovery: validation and methodologic issues. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38(7):1980–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]