Social determinants of health

(SDOH), such as education, occupation, housing, and social support, are widely recognized as key drivers of poor clinical outcomes, health care inequities, and escalating health care costs.1 The 2019 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease recommend, for the first time, that clinicians consider social risk in clinical risk assessment for cardiovascular events.2At the same time, in the policy community there is increasing emphasis on collecting SDOH data to improve risk adjustment, facilitatelinkage with community partners, and prioritizestate and federal policy efforts.

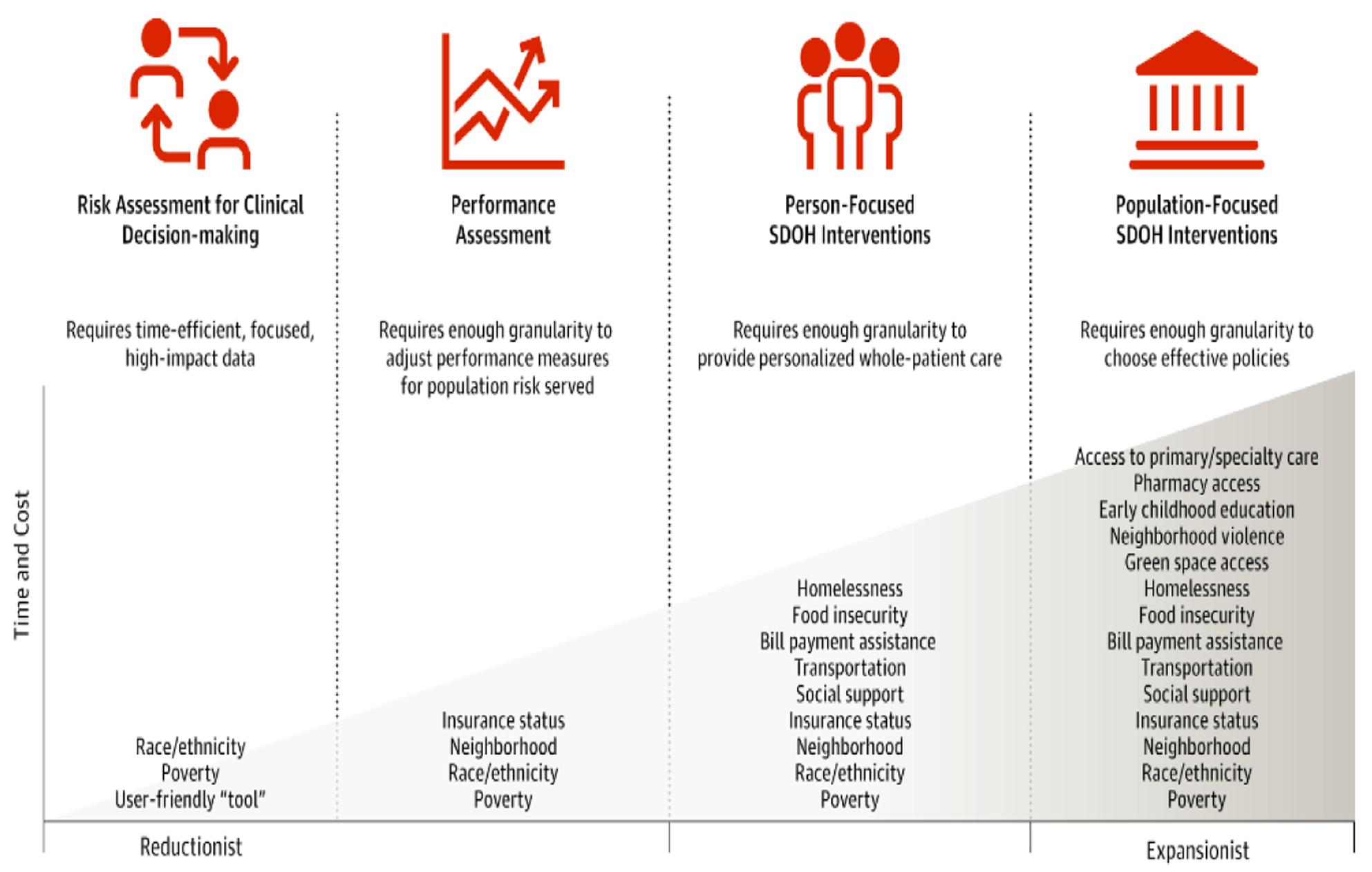

But how to collect these data, who should collect it, how much data are needed, and how it should be used remain unclear. Should the approach be reductionist and focus on collection of only a few key pieces of information with high explanatory power? Should it be expansionist and aim to collect detailed social histories from all patients analogous to how medical histories are taken? The answer depends on the intended use of the data (Figure).

Figure.

Proposed Schematic for Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Data

Use Case 1: Clinical Assessment and Risk Prediction

Clinicians on the front lines of providing cardiovascular care are keenly aware of the effect of SDOH on their patients’ lives. At the same time, the demands they face in terms of documentation and productivity make it hard to imagine how additional data collection on SDOH could be added to a typical encounter. It might be daunting to ask about social factors without clear direction on what to do with the information. It is also difficult for clinicians to know how to incorporate such data into clinical decision-making; while it is known SDOH are associated with clinical outcomes, there is little guidance on what this should mean for prevention and treatment strategies. This set of issues has left many clinicians avoiding the subject altogether, which does not move us meaningfully in the right direction.

For the purposes of clinical assessment and risk prediction, the most reasonable approach is likely a reductionist approach. To quickly and effectively treat patients, clinicians need the least amount of data that accurately capture incremental increases in risk attributable to SDOH. Cardiovascular risk prediction models underpredict risk in populations with high social risk compared with those with low social risk3; it is possible that even the addition of 1 variable, such as poverty, to existing models may improve risk assessment meaningfully. A simple screening tool of 1 or 2 questions may have a role here, with positive screens triggering a referral for a more extensive assessment. However, these data would still need to be consolidated into concrete, usable information integrated into clinical workflow.

Use Case 2: Performance Evaluation

Another important use of SDOH data is in risk adjustment for performance assessment. To avoid erroneously penalizing clinicians and systems who care for socially high-risk populations, enough data granularity is required to facilitate adjusting performance measures for the level of social risk of the populations they serve.4 Emerging evidence suggests that several key factors, such as insurance status and poverty, can significantly affect performance measurement on measures such as readmissions for heart failure or acute myocardial infarction.5 Ongoing testing of existing performance measures will provide valuable insight into exactly which elements are high yield in terms of improving models, but here one cannot let perfection be the enemy of “good enough.” Data collection for these purposes should be automated when at all feasible, and a small number of high-fidelity data elements will likely suffice.

Use Case 3: Person-Focused SDOH Interventions

When an initial screening suggests that SDOH are likely playing a role in a patient’s health, a more thorough assessment of each element is warranted: here, an expansionist approach is needed. Such evaluation, best conducted by individuals with training in social work, case management, or care coordination, requires a careful, thorough needs assessment across a range of SDOH. Only with thorough data collection can interventions best be tailored to each individual. For example, if a patient with heart failure were to screen positive on a simple SDOH question, a follow-up evaluation might focus on determining the details of the individual’s living situation or transportation needs that might affect their ability to take a complex medication regimen or attend follow-up appointments. Patients can then be linked with the appropriate support services, such as housing assistance and medical transportation, to maximize their chance of achieving good health outcomes.

Use Case 4: Local, State, and Federal Population-Based Interventions and Policies

In an increasingly value-based payment structure, hospital systems need SDOH data to know how to meet the needs of at-risk populations. The ability to coordinate with existing community services and design new community programs will require community-specific information.6 For example, rural communities might face very different transportation challenges than urban ones; only by collecting these data can solutions be prioritized to meet community needs. And with the broadest possible scope, local, state, and federal policy makers need enough detail to enact policies that move further upstream to target the root causes of so many social determinants: lack of economic opportunity and entrenched poverty. Only by quantifying the degree to which the failure to address SDOH has led to poor health outcomes and high health spending can the policy landscape be altered to prioritize further interventions in this area. Data collection for these purposes should be population-based samples, allowing for a detailed analysis with representative groups that can then generalize much more broadly than the sampling that could take place in a clinic or hospital.

Conclusions

In sum, there is a time and place for both a reductionist and an expansionist approach to data on SDOH. One of the most common pearls of wisdom one will hear in the halls of a teaching hospital is “if it is not going to change what you do, do not order it.” For now, most physicians have taken this approach to SDOH. But operating ignorant of social risk is no longer an option if the objective is to help patients achieve the best clinical outcomes possible and may have the highest cost and clinical consequences among those in the highest social risk groups. If the goal is reduced healthcare inequities and improved population health, the medical community will need to adapt, get concrete, and get practical about the use of social determinants data.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Hammond is supported by T32 HL007081 from the Washington University School of Medicine. Dr Joynt Maddox receives research support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL143421), National Institute on Aging (R01AG060935), and the Commonwealth Fund and previously did contract work for the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Contributor Information

Gmerice Hammond, Cardiovascular Division, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, St Louis, Missouri..

Karen E.Joynt Maddox, Center for Health Economics and Policy, Institute for Public Health at Washington University in St Louis, St Louis, Missouri..

REFERENCES

- 1.Valentine NB, Koller TS, Hosseinpoor AR. Monitoring health determinants with an equity focus: a key role in addressing social determinants, universal health coverage, and advancing the 2030 sustainable development agenda. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:34247. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.34247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019;2019: CIR0000000000000678.31815538 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colantonio LD, Richman JS, Carson AP, et al. Performance of the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease pooled cohort risk equations by social deprivation status. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(3): e005676. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joynt Maddox KE. Financial incentives and vulnerable populations: will alternative payment models help or hurt? N Engl J Med. 2018;378(11): 977–979. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1715455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joynt Maddox KE, Reidhead M, Hu J, et al. Adjusting for social risk factors impacts performance and penalties in the hospital readmissions reduction program. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(2):327–336. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor LA, Tan AX, Coyle CE, et al. Leveraging the social determinants of health: what works? PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0160217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone. 0160217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]