Abstract

Stress-coping styles dictate how individuals react to stimuli and can be measured by the integrative physiological parameter of resting heart-rate variability (HRV); low resting HRV indicating proactive coping styles, while high resting HRV typifies reactive individuals. Over 5 successive breeding seasons we measured resting HRV of 57 lactating grey seals. Mothers showed consistent individual differences in resting HRV across years. We asked whether proactive and reactive mothers differed in their patterns of maternal expenditure and short-term fitness outcomes within seasons, using maternal daily mass loss rate to indicate expenditure, and pup daily mass gain to indicate within season fitness outcomes. We found no difference in average rates of maternal daily mass loss or pup daily mass gain between proactive and reactive mothers. However, reactive mothers deviated more from the sample mean for maternal daily mass and pup daily mass gain than proactive mothers. Thus, while proactive mothers exhibit average expenditure strategies with average outcomes, expenditure varies much more among reactive mothers with more variable outcomes. Overall, however, mean fitness was equal across coping styles, providing a mechanism for maintaining coping style diversity within populations. Variability in reactive mothers’ expenditures and success is likely a product of their attempts to match phenotype to prevailing environmental conditions, achieved with varying degrees of success.

Subject terms: Behavioural methods, Behavioural ecology, Animal behaviour

Introduction

Despite the remarkable growth over recent decades in research on consistent individual differences in behaviour (under various terms such as personality, temperament, behavioural types and coping styles), there remains much debate about the adaptive value and fitness consequences of such inter-individual variation and the mechanisms by which such variation can be maintained within populations and species1–6. Ultimately the question remains; if one behavioural type has an apparent fitness advantage over others7,8, then how might variation in behavioural types be maintained in wild populations4? Smith and Blumstein’s9 meta-analysis showed that across a broad range of taxa, bolder individuals tended to achieve increased reproductive success, but often with greater risk of mortality, suggesting that balancing rewards and costs of boldness may vary in different contexts. Other studies have indicated that different behavioural types might prosper under different environmental conditions and that spatial or temporal variation in local conditions might maintain inter-individual variation within populations10. Therefore, the context- or situation-dependent balances between costs and benefits of different behavioural types have been considered key determinants of inter-individual variation within wild populations.

Most studies of personality are conducted in captive, laboratory settings, or at least temporarily remove animals from the wild in order to conduct behavioural tests in more controlled settings10,11 or monitor responses during capture and handling events12,13. As behavioural expression is often context dependent, patterns of inter-individual variation expressed in arguably abstract laboratory conditions or under acute stress may not always be expressed in the range of natural conditions a species experiences14,15, though see16. Thus, an increasing number of studies are attempting to assess personality and its consequences in natural wild settings, where inter-individual variation will have its ecologically and evolutionary relevant consequences14,17–20.

Consistent individual differences in behaviour are typically identified through repeatability of individual behaviour in experimental tests designed to yield metrics that can be interpreted in terms of a particular personality axis, such as the widely used bold-shy axis7–11 or variation in exploration10. While some behavioural test scenarios, such as an open field test, might be applicable to many species, tests often must be tailored to the particular mechanics (e.g. mode of locomotion) and sensory capabilities of the subject species. Thus, tests, and the behavioural metrics extracted, can be very species specific, particularly when attempting to conduct behavioural tests in situ, where local environmental conditions may also dictate experimental design17,20,21. Consequently, identifying clear commonality in the meaning of behavioural tests across multiple species can be challenging22–24. This limits the scope for comparative studies, which are key to unravelling broader evolutionary patterns and ecological relevance of consistent individual differences in behaviour1,14,25–27.

Physiological indicators of inter-individual differences can alleviate some of these limitations, especially if based on a fundamental physiological system that spans a wide taxonomic range. Resting heart rate variability (HRV) is a measure of the degree of variation in successive inter-beat (or R-R) intervals (IBI’s) while an individual is in a stationary condition and can be used to differentiate between individuals in terms of their stress-coping styles in a wide range of mammals28–33. The primary axis of coping styles is the pro-reactive axis. Proactive individuals form routines readily, express little behavioural flexibility and are less responsive to environmental stimuli. Conversely, reactive individuals are more flexible, making them more responsive to environmental stimuli29,30,34. HRV represents the combined effects of the parasympathetic and sympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system on the heart’s pacemaker, the sinoatrial node31,32. At rest, reactive individuals have relatively high parasympathetic activity, resulting in higher HRV, whereas proactive individuals are dominated by sympathetic activity, resulting in reduced HRV28,31,32. However, there are very few studies that have measured a physiological indicator of individual coping style in a wild population35, with most physiological studies of coping style focusing on laboratory or captive animals29,34. Likewise, studies of resting HRV are based on data from laboratory bred specimens, domestic livestock or companion animals28–33.

With the development of heart rate monitors capable of recording IBI’s at millisecond precision it is possible to derive HRV measures on wild animals in situ while undergoing their normal daily activity. We deployed specially modified heart rate monitors on lactating grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) to assess across individual variation and within individual consistency in resting HRV over successive breeding seasons. Female grey seals have been shown to exhibit consistent individual differences in behaviour17,36 including in behavioural plasticity reflecting pro- and reactive stress-coping styles17,37. As coping styles represent a spectrum of approaches for dealing with life’s challenges34,38,39, it is likely that they are associated with inter-individual differences in reproductive success. Kontiainen et al.40 showed that proactive Ural owl (Strix uralensis) females produced more recruits, though such differential success again raises the question of how variation in coping styles is maintained. Monstrier et al.12 also showed enhanced offspring survival for proactive mothers in roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), but in this case success was habitat dependent, with reactive mothers faring better in certain habitats. Therefore, it is plausible that proactive and reactive grey seal mothers may vary in measures of reproductive success.

Grey seals in the UK are true capital breeders with spatially and temporally separate reproduction and foraging. Females fast during the autumnal breeding season, relying on stored reserves to provision themselves and their single pup throughout the 18–20 day lactation period, effectively providing a closed system for the assessment of reproductive expenditure41. All energy required for maintenance and reproduction is derived from foraging at sea outside of the breeding season. Thus, a female grey seal’s annual foraging success is expressed in her maternal post-partum mass, which sets limits on her consequent material expenditure on that year’s pup41. During lactation, maternal daily mass loss rate (kg/day) represents dynamic or average maternal expenditure during the current reproductive event, while pup daily mass gain rate (kg/day) provides an index of the short-term (within season) fitness outcomes of maternal expenditure, and the ratio of maternal daily mass loss rate to pup daily mass gain rate provides a measure of mass transfer efficiency41. This study system, therefore, provides the opportunity to examine how individual coping style is related to measures of individual condition, reproductive expenditure and success, allowing us to test for differences in fitness outcomes with respect to an individual’s position on the pro-reactive spectrum. Over 5 successive breeding seasons (2013–2017) we measured resting HRV of 57 lactating grey seals. First, we show that measures of resting HRV for individuals are repeatable over successive breeding seasons, indicating long-term consistent-individual differences in pro-reactivity. Then we ask whether proactive and reactive mothers differ in measures of maternal reproductive expenditure (maternal daily mass loss rate) and short-term (within breeding season) fitness outcomes (pup daily mass gain rate and mass transfer efficiency). However, as reactive individuals are predicted to exhibit greater flexibility than proactive individuals, either in terms of behaviour or physiology29,30, we predicted that reactive individuals would exhibit greater inter-individual variation relative to proactive individuals in these measures of maternal reproductive performance. Therefore, for each individual, we computed the modulus (the absolute value) of the deviance from the sample mean within each year for each of these metrics (maternal post-partum mass, maternal daily mass loss rate, pup daily mass gain rate and mass transfer efficiency) to determine whether reactive individuals tended to deviate more from annual means of these mass metrics compared to more proactive individuals.

Results

Repeatability of HRV across years

Repeatability of the resting HRV estimates for the 25 mothers that had heart rate recorded for more than one season was high (R = 0.630 ± 0.113, CI = 0.367–0.802, LRT p < 0.0001). Repeatability within individuals was also high in most individuals (Ri range = 0.302–0.999, median = 0.686, LQ = 0.582, UQ = 0.936).

HRV and maternal allocation/pup growth

Resting HRV exhibited no discernible influence on the real values of maternal post-partum mass, maternal daily mass loss rate, pup daily mass gain rate, or mass transfer efficiency. Birth date was retained in the best model for absolute values of maternal post-partum mass, maternal daily mass loss rate, and pup daily mass gain rate (Table 1). Mothers that pupped later in the season tended to have lower post-partum masses, though post-partum mass was strongly influenced by individual ID (86% of variation accounted for by ID). As expected, post-partum mass was found to have a strong effect on both maternal daily mass loss rate and pup daily mass gain rate, where heavier mothers were found to have higher rates of mass loss, but also higher rates of pup mass gain (Table 2). However, for a given maternal post-partum mass, those that pupped later in the season tended to exhibit higher rates of maternal daily mass loss and pup daily mass gain (Table 2). Year also had a strong effect on the mass change parameters. In 2015 there were significantly higher rates overall for maternal daily mass loss (Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test by Year: Χ2 = 13.97, df = 4, p = 0.0074) and pup daily mass gain (Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test: Χ2 = 12.82, df = 4, p = 0.0123) relative to the other breeding seasons. However, the putative interaction between resting HRV and year was not retained in any of the confidence sets for any of the tested response variables. None of the parameters tested, however, appeared to explain observed differences in mass transfer efficiency as the null model was the only model remaining after model selection (Table 1). Device type (see methods) did not feature in any of the confidence sets for any of the tested response variables.

Table 1.

Retained GLMMs for predicting mass and mass change proxies of short-term fitness, and the modulus of the deviance from the sample mean for each of these proxies.

| Response variable | Model structure | df | AICc | ΔAIC | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPPM | Birthdate | 4 | 210.2 | 0 | 0.287 |

| Null | 3 | 215.1 | 4.89 | 0.025 | |

| MDML | Year + birth date + MPPM | 9 | 238.5 | 0 | 0.262 |

| Year + MPPM | 8 | 239.2 | 0.66 | 0.188 | |

| Null | 3 | 274.9 | 36.38 | 0 | |

| PDMG | Year + birth date + MPPM | 9 | 252 | 0 | 0.418 |

| Year + MPPM | 8 | 254.1 | 2.08 | 0.147 | |

| Null | 3 | 274.6 | 22.58 | 0 | |

| MTE | Null | 3 | 277.6 | 0 | 0.425 |

| MPPM DEVIANCE | Birth date + HRV | 5 | 235.2 | 0 | 0.329 |

| Birth date | 4 | 236.3 | 1.14 | 0.186 | |

| Null | 3 | 238.5 | 3.33 | 0.062 | |

| MDML DEVIANCE | Birth date + HRV | 5 | 252.6 | 0 | 0.315 |

| Birth date | 4 | 256.6 | 4.02 | 0.042 | |

| Null | 3 | 261.7 | 9.03 | 0.003 | |

| PDMG DEVIANCE | Birth date + HRV | 5 | 265.5 | 0 | 0.389 |

| Birth date | 4 | 268.2 | 2.65 | 0.103 | |

| Null | 3 | 274.2 | 8.67 | 0.005 | |

| MTE DEVIANCE | Null | 3 | 271.4 | 0 | 0.224 |

Null model results are also provided for comparison, even if not retained in confidence set. All models contained ID as a random effect. Nobs = 95, NID = 57. Abbreviations: HRV = Resting heart rate variability, MPPM = maternal post-partum mass, MDML = maternal daily mass loss rate, PDMG = pup daily mass gain rate, MTE = mass transfer efficiency.

Table 2.

Coefficient estimates for the retained fixed effects in the best model from Table 1 (ΔAIC = 0; Table 1) for each response variable.

| Response variable | Fixed/random effect | Coefficient estimate | Standard error | P value | R2 | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPPM (86%) | Intercept | −0.047 | 0.135 | <0.0001 | 0.092 | 0.013–0.225 |

| Birth date | −0.253 | 0.092 | 0.006 | 0.092 | 0.013–0.225 | |

| MDML (16%) | Intercept | −0.041 | 0.239 | <0.0001 | 0.436 | 0.321–0.580 |

| Year (2014) | 0.265 | 0.314 | 0.0002 | 0.007 | 0.000–0.080 | |

| Year (2015) | 0.944 | 0.273 | 0.105 | 0.019–0.242 | ||

| Year (2016) | 0.304 | 0.284 | 0.011 | 0.000–0.092 | ||

| Year (2017) | 0.141 | 0.277 | 0.003 | 0.000–0.064 | ||

| Birth date | 0.165 | 0.093 | 0.076 | 0.039 | 0.000–0.148 | |

| MPPM | 0.571 | 0.090 | <0.0001 | 0.347 | 0.208–0.489 | |

| PDMG (12%) | Intercept | −0.327 | 0.258 | <0.0001 | 0.329 | 0.218–0.493 |

| Year (2014) | 0.475 | 0.343 | 0.0002 | 0.020 | 0.000–0.111 | |

| Year (2015) | 0.810 | 0.298 | 0.071 | 0.005–0.196 | ||

| Year (2016) | 0.262 | 0.310 | 0.007 | 0.000–0.081 | ||

| Year (2017) | −0.185 | 0.303 | 0.004 | 0.000–0.069 | ||

| Birth date | 0.206 | 0.096 | 0.031 | 0.054 | 0.002–0.171 | |

| MPPM | 0.446 | 0.093 | <0.0001 | 0.220 | 0.095–0.370 | |

| MPPM DEVIANCE (63%) | Intercept | 0.063 | 0.117 | <0.0001 | 0.126 | 0.036–0.274 |

| Birth date | 0.255 | 0.103 | 0.013 | 0.086 | 0.010–0.217 | |

| HRV | 0.219 | 0.117 | 0.061 | 0.065 | 0.004–0.188 | |

| MDML DEVIANCE (37%) | Intercept | 0.032 | 0.110 | <0.0001 | 0.182 | 0.072–0.336 |

| Birth date | 0.336 | 0.104 | 0.0011 | 0.129 | 0.031–0.270 | |

| HRV | 0.285 | 0.110 | 0.0099 | 0.095 | 0.014–0.229 | |

| PDMG DEVIANCE (7%) | Intercept | −0.003 | 0.099 | <0.0001 | 0.149 | 0.050–0.300 |

| Birth date | 0.334 | 0.098 | 0.0007 | 0.117 | 0.025–0.256 | |

| HRV | 0.235 | 0.010 | 0.0186 | 0.061 | 0.003–0.182 |

Mass-transfer efficiency (MTE) was best explained by the null model and therefore not included here. The percentage values beside each response variable denote the stochastic variation accounted for by ID derived from conditional and marginal coefficients of determination computed using r.squaredGLMM from the MuMIn package93,96. The table also provides R2 (with 95% confidence intervals) for fixed effects within the best models (derived using r2beta96). Abbreviations: HRV = Resting heart rate variability, MPPM = maternal post-partum mass, MDML = maternal daily mass loss rate, PDMG = pup daily mass gain rate, MTE = mass transfer efficiency.

HRV and deviance from seasonal means

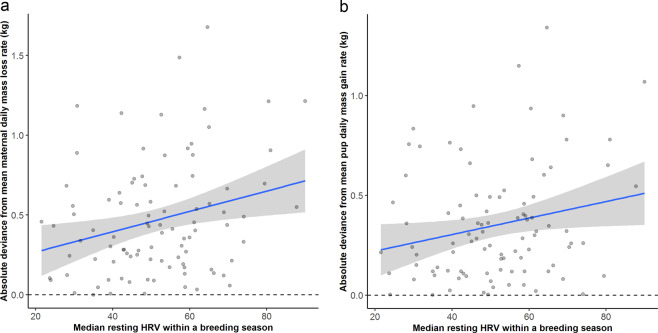

Resting HRV appears to be influential in the degree of individuals’ deviation from annual mean rates of maternal mass loss and pup mass gain, though not for deviance in maternal post-partum mass or mass transfer efficiency. Females who gave birth later in the season were found to deviate more from the annual mean with respect to post-partum mass (Tables 1 and 2), which was again strongly influenced by individual ID (accounting for 63% of the model variation). While resting HRV was also retained in the best model, with more reactive individuals having more variable post-partum masses, the effect was non-significant. However, these results should be considered with caution as the null model was also retained in the confidence set (Table 1, ΔAIC Null = 3.33). By contrast, resting HRV was retained as a significant effect in our models of the degree of deviation from annual mean rates for maternal mass loss and pup mass gain (Fig. 1a,b). More reactive individuals appeared to exhibit greater variation in maternal daily mass loss rates as well as greater variation in pup daily mass gain rates than proactive individuals (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 1a,b). Birth date was also retained, with mothers pupping later in the season exhibiting greater variation in rates of maternal mass loss and pup mass gain. In contrast to maternal post-partum mass, individual ID appeared to account for little variation in the deviance of maternal daily mass loss rate (37% of model variation) and pup daily mass gain rate (7% of model variation). Only the null model was retained in the confidence set for deviance in mass transfer efficiency model (Table 1). None of the confidence sets retained the putative interaction between Resting HRV and year and device type did not feature in any of the confidence sets for any of the tested response variables.

Figure 1.

The effect of resting heart rate variability (HRV) on (a) the modulus of the deviance from annual mean values for rates of maternal daily mass loss, and (b) the modulus of the deviance from annual mean values for rates of pup daily mass gain. Annual mean represented by dashed line at y = 0.0. Line of best fit in blue with shaded area representing 95% CI. Points are raw data values.

Discussion

In our study we use a physiological measure of coping style, resting HRV, which is based on a physiological system that is highly conserved across vertebrates, and underpins behavioural patterns29,30,34. We show high inter-annual repeatability in resting HRV among female grey seals in an entirely natural setting, demonstrating across individual differences and long-term within individual consistency in stress-coping style on the pro-reactive spectrum. In addition, these different coping styles exhibit subtle differences in patterns of reproductive performance that suggest a mechanism by which inter-individual variation in coping style can be maintained within a wild population subject to natural environmental conditions.

Coping style did not influence real values of maternal size (post-partum mass), maternal performance (maternal daily mass loss rate, mass transfer efficiency), or short-term reproductive outcomes in terms of pup growth rates (pup daily mass gain rate). Therefore, across the sampled population, pro- and reactive mothers did not differ significantly in their initial state on arrival at the colony, their in-year expenditure, or their reproductive outcome. It is notable that we found no effect of coping style on the deviance from population mean values of maternal post-partum mass. Therefore, reactive mothers are not necessarily returning to the breeding colony in more variable states, suggesting that both pro- and reactive mothers are faring equally well overall in terms of net mass gain during the at-sea foraging phases of their lifecycle. It seems therefore that the mass change consequences of stress-coping style reveal themselves more on the breeding colony. Individual ID accounted for a large proportion of the variation in both absolute measures of maternal post-partum mass (86%) and deviance from mean post-partum mass (63%). This is indicative of individual differences in overall body size (as opposed to mass) and likely foraging success prior to the breeding season that are independent of coping style; a larger mother will always be larger. Whether pro- and reactive individuals adopt different, but equally successful, foraging strategies (e.g. specialist vs. generalist) while at sea is an area that requires further research.

By contrast, coping style appears to strongly influence the extent of inter-individual variability in our reproductive performance measures. Reactive mothers deviated more from the annual population mean in terms of their daily mass loss and in the daily mass gain of their pups. Proactive mothers exhibited a more consistent mean expenditure and outcome. This coping style effect was independent of pupping date and maternal post-partum masses which are known to influence maternal expenditure and consequent pup growth outcomes in grey seals41. These results demonstrate a reproductive pattern that can maintain inter-individual variation in stress-coping styles within a natural population. Overall, there was no net difference in fitness proxies across the spectrum of coping styles in terms of individual expenditure or outcomes. Therefore, there is likely no net selective advantage to being either proactive or reactive in terms of within season reproductive performance, at least under the environmental conditions that seals experienced during this study (indicated by the lack of evidence for an interaction between coping style and year in our models). There are very few empirical studies that directly show a link between coping style and fitness outcomes in natural environments, and the results of these efforts are mixed12,40. Kontiainen et al.40 found evidence that in conditions of temporally variable food availability proactive Ural owl mothers were more successful overall than reactive mothers. Monestier et al.’s12 study of coping-style in roe deer, showed that pro- and reactive mothers fare better in different habitats, providing a spatially dependent advantage to each coping style. Studies of personality (as opposed to coping style) in non-human animals suggest similar differential trade-offs for individuals across a personality spectrum. For example, the differential success of fast and slow exploring great tits (Parus major) across breeding seasons depending upon habitat resource quality10. A similar pattern of changing costs and benefits of boldness dependent upon spatio-temporal changes in resources was also found in Eurasian red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris42). Such processes represent potential solutions to the conundrum of the maintenance of inter-individual variation in natural populations through differential costs and benefits dependent upon either spatial or temporal variation in environment4. In contrast, our results from studying female grey seals in their natural habitat suggested proactive mothers were not more successful, but instead were more uniform in their reproductive performance than reactive mothers, maintaining expenditure and outcomes closer to the mean values for the cohort.

Why should reactive mothers show greater variability in their reproductive expenditure (and consequently pup growth rates) than proactive mothers? Reactive individuals tend to be more responsive to environmental stimuli and consequently exhibit greater behavioural flexibility. Proactive individuals are less responsive to environmental stimuli, express little behavioural flexibility and form routines more readily29,30,34,43. Therefore, it is likely that reactive grey seal mothers tend to invest more or less than average in their current reproductive episode dependent upon the conditions prevailing at the time. A range of local, fine-scale spatial and temporal environmental factors have already been shown to strongly influence the behaviour of grey seal mothers on breeding colonies44–50. Grey seals are typically highly site-faithful to breeding colonies in the UK and tend to occupy similar parts of a colony year after year51. Furthermore, once mothers have pupped, they tend to be ‘tied’ to a small area of the colony due to the limited mobility of the pup51. However, conditions at each locality vary within and between breeding seasons46–48, and a grey seal is clearly unlikely to be able to predict future conditions prior to pupping. Therefore, we might expect reactive individuals to modify their behaviour and/or physiology to attempt to match the prevailing environmental conditions (phenotype-environment matching4,43,52), whereas proactive mothers will adopt an average ‘one size fits all’ approach. The reactive strategy is essentially a high reward but high-risk strategy. If a mother’s phenotype successfully matches to the prevailing conditions, then she is likely to be able to focus her investment in her current pup. If, however, she fails to appropriately match her phenotype to the conditions then she is likely to have to expend energy on other potentially costly activities (e.g. aggression, locomotion), reducing expenditure on her pup. There are various reasons why phenotypically plastic individuals may fail to successfully match their phenotype to the environment, including energetic and physical costs of, and limits to, plasticity but also where the environment changes too rapidly or unpredictably for an individual to make the appropriate changes in time53. Individuals with a reactive coping style may experience higher rates of mass loss due to the action of catabolic hormones (corticosteroids) which are in integral part of the suite of correlated traits defining coping styles29,30,34,54. Future studies could seek to measure not only coping style (using resting HRV), but also individual reactivity30 using stress hormones such as cortisol. Pro- and reactive individuals will likely respond differently to handling and sampling, which may provide a useful indicator of stress-reactivity if appropriately standardised.

Our results and their implications are particularly pertinent in the context of current rapid environmental change. Climate driven local weather patterns are becoming more variable and unpredictable55. Previous work has shown that grey seal behaviour and success on the breeding colony are weather dependent, particularly with respect to temperature and rainfall and their influence on thermoregulation and consequently behaviour46–48,50. However, grey seals are not alone in being subjected to ever more variable and unpredictable conditions during key phases of their lifecycle that are tied to specific seasons (e.g.56). Such changing environmental patterns will inevitably impact differentially upon proactive and reactive individuals within populations27,57,58. Therefore, assessing the extent of variation in coping styles within wild populations and their responses to changing environmental conditions is a vital step in understanding species resilience to rapid environmental change. Species able to cope with anthropogenic disturbance are likely to be those that contain some portion of behaviourally flexible individuals, rather than being species that are tolerant of human activities per se59. Although it remains unclear how directly linked the physiological underpinnings of coping styles and behavioural aspects of personality are38,60, coping styles are linked to the degree of behavioural flexibility that individuals may be able to express29,30,34,38,39,43,61. Given that the basic structure of the mammalian autonomic nervous system and the interplay of sympathetic and parasympathetic branches are highly conserved, it is probable that the behavioural and physiological distinctions between pro- and reactive types represent a fundamental biological pattern that can be observed in many mammalian species and indeed vertebrates more generally29,30,34,43. Consequently, findings from this study will have general applicability and broad relevance across vertebrate species.

Methods

Study site and years

The study was conducted during the annual grey seal breeding season at the Isle of May, Scotland (56.1856° N, 2.5575° W) in the years 2013 to 2017. From late October to early December, individual females spend 18–20 days on the island, during which time they each bear and nurse one pup, enter oestrus approximately 16 days post-parturition62, mate, and abruptly wean their pup around day 18 of lactation41. The Isle of May colony was part of a long-term study of grey seal reproductive energetics and behaviour by the Sea Mammal Research Unit, SMRU41,63. Known individuals can be identified using pre-existing brands, flipper tags and/or pelage patterns41,64. A subset of known breeding females are routinely handled each year by SMRU to obtain morphometric data, with individual females being captured and measured twice during their stay on the colony; once early in lactation (within 5 days of parturition) and once late in lactation (approx. day 14–16 after parturition). We used these handling events to deploy heart rate monitors on known females during the first capture, and to recover them at the second capture. Our focus was on re-deploying devices on the same individuals over multiple-years where possible to gain data on inter-annual consistency of resting HRV. Where individuals did not return or were not available to capture in a particular year, we then completed the annual sample size by including other mothers from the group of known individuals within the long-term study of grey seals on the Isle of May. Details of the standard capture procedure are published elsewhere41,65,66.

Derivation of resting HRV estimates

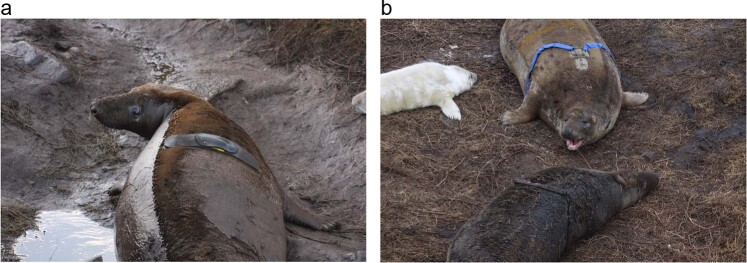

We instrumented focal seals with externally mounted heart rate monitors that provide millisecond precision measurements of IBIs through accurate detection of RR peaks32,67 and transmit these data to remote receivers. In the 2013 and 2014 seasons we used modified Polar H2/H3 monitors (Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland) which transmitted IBI data to Polar RS800CX heart rate receivers. Polar devices have been validated for the recording of HRV in a range of domesticated mammalian species31–33,67–71. In 2013 the Polar monitors were attached to Polar soft strap electrodes extending 14 cm either side of the midline of the monitor. These electrode straps were mounted dorsally, just behind the right shoulder blade, extending laterally to the left and right. The entire unit was covered with a neoprene patch to provide protection and retain electrode gel (Fig. 2a; see72 for full design details). In 2014 this design was improved by replacement of the short Polar soft strap electrodes with two 50 cm protected cables leading to silver chloride electrodes located immediately posterior of the left and right fore-flippers providing more optimal electrode placement (Fig. 2b). The Polar system requires each monitor to be paired to a single receiver located within approximately 20 m72, which can constrain data collection especially in wild, free ranging animals. Therefore, in 2015–2017, we switched to using Firstbeat heart rate monitors (https://international-shop.firstbeat.com/product/team-pack/) as these provided a much increased signal transmission range (up to 200 m line of sight), and the capability to record multiple monitors (up to 80) at a single receiving station. These monitors were again modified with the extended electrodes (Fig. 2b). In all seasons, IBI data were collected during daylight hours only.

Figure 2.

Two versions of telemetry devices were used to monitor heart rate variability for breeding female grey seals. (a) shows a neoprene strap containing a Polar H2/H3 monitor and Polar soft strap electrode, as used during the 2013 breeding season on the Isle of May, Scotland. (b) shows two neighbouring females equipped with Firstbeat heart rate monitors (as used in 2015–2017) with the extended electrode cables leading to silver chloride electrodes located immediately posterior of the left and right fore-flippers (as used in 2014–2017). The monitor is located centrally on the seals’ back. The monitor, cables and electrodes are protected by a covering of ballistic nylon. The female at the top of this image, is the same female as shown in Fig. 1a in the 2013 breeding season.

Artefacts in IBI data can lead to significant biases in estimates of HRV32,67,73. Sources of artefacts in IBI data can be intrinsic (e.g. arrhythmias, noise from muscle action potentials), or extrinsic (e.g. equipment malfunction, electromagnetic potentials), causing beats to be either missed or spuriously generated, leading to erroneously long or short IBI values32,67,72. We examined our raw IBI data for potential artefacts using Firstbeat Sports software (v.4.5.0.274) and RHRV75 which detect extreme values and make corrections by deletion of spurious extra beats (extreme short IBIs) or interpolation for missing beats (extreme long IBIs). Artefacts that involve invariable sequences of IBIs (flats) or sequences of monotonically increasing or decreasing IBIs (stairs) cannot be corrected33, therefore these were identified using bespoke R scripts written by the authors (NB, AMB, SDT) to permit subsequent filtering of IBI traces with excessive flats and stairs72. IBI traces were then segmented into non-overlapping 300-second periods32 and HRV was computed as the root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) between IBIs using RHRV. Although there are several measures of sympathovagal balance that can be computed from IBI data32, RMSSD is a preferred metric for use under free-running conditions because it is affected less by respiratory cycles76,77 and provides a measure that is relatively easy to interpret32,77. Any 300-second traces that had >5% flats or stairs were removed from subsequent analyses32,33,72.

Each IBI in the remaining traces was matched with a behavioural state derived from in-field video footage recorded concurrently with the IBI data collection. Video footage was decoded by experienced observers (n = 4) post-field season using a focal sampling protocol78 and a bespoke Visual Basic for Applications Macro in Microsoft Excel to record behaviours based on a pre-established ethogram37,46,72,79. In order to define resting HRV, the behavioural state of interest for this study was Resting (defined as the female remaining largely motionless, lying prone or supine with head in contact with the ground, eyes open or closed). All observers were trained to the same ethogram by SDT, and inter-observer reliability was tested on two hours of example video footage, showing high levels of agreement (ICC2 = 0.96, F16,48 = 109, p < 0.0001, 95% C.I. = 0.93–0.99; comparison across four independent observers based on 17 behavioural categories, of which Resting is one). Resting behaviour is relatively easy to identify reliably and tends to comprise the bulk of a breeding grey seal’s activity budget (typically over 60%37,45,46,79–81). Resting HRV was computed only from 300-second periods where the seal was at rest for ≥95% of the IBIs (and where the remaining time did not involve high energy behaviours such as locomotion or aggression). As our measure of resting HRV we computed the median RMSSD from all 300-second traces for each seal in each breeding season (number of 300 second traces per female per year ranged from three to 333, median = 32).

Mass and mass change proxies of maternal expenditure and short-term fitness outcomes

Females and their pups were weighed at each capture as described in Pomeroy et al.41. Mass data were used to calculate three measures of maternal reproductive performance41; maternal post-partum mass (kg), maternal daily mass loss rate (kg/day), and pup daily mass gain rate (kg/day). Maternal post-partum mass was estimated using maternal daily mass loss rate to extrapolate a mother’s mass on the date of first capture to her parturition date as determined through in-field observations of the known females. Maternal post-partum mass provides a measure of maternal size and condition at a standardised time point (immediately after parturition) and is an index of realised somatic growth and foraging success prior to the breeding season41. As pup daily mass gain rate is influenced by pup physiology and behaviour as well as the maternal expenditure41,65,80–84 we also computed the ratio of daily rates of maternal mass loss: pup mass gain as a measure of maternal mass transfer efficiency.

We used our real values of maternal post-partum mass, maternal daily mass loss rate, pup daily mass gain rate, and mass transfer efficiency to examine whether proactive and reactive mothers differed in any of these proxies of maternal reproductive performance. However, as previous studies argue that reactive individuals are more likely to exhibit flexibility, either in terms of behaviour or physiology29,30,34, we also examined whether reactive individuals tended to deviate more from annual means of these mass metrics compared to more proactive individuals. Therefore, for every individual, we computed the modulus (the absolute value) of the deviance from the sample mean within each year for each of these metrics. We chose to use deviance from the annual mean (as opposed to a grand mean across all five years) to account for any interannual differences in seal behaviour and energetics which may have been driven by prevailing weather conditions at the breeding colony and consequent access to water across the population37,46–50.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted in R version 3.5.085. For females with measures of resting HRV for more than one season (Table 3) we determined population level repeatability (R86,87) using the ‘rptR’ package88 with individual as a random effect and the number of measures per individuals as a fixed effect, with parametric bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals computed from 1,000 simulations. We also derived repeatability estimates for every individual (Ri) by dividing the between-individual variance (σ2α) by the sum of between-individual variance and the residual variance for each individual20.

Table 3.

Summary of number of seals for which resting HRV estimates were obtained and the number of individuals with repeat measures across years.

| No. of years with resting HRV estimate | No. of seals |

|---|---|

| 1 | 32 |

| 2 | 16 |

| 3 | 6 |

| 4 | 2 |

| 5 | 1 |

We examined the effect of resting HRV on mass and mass change proxies of fitness by fitting generalized linear mixed-effects models (GLMM) within the R package lme489. Female ID was included as a random effect to account for pseudoreplication of individuals across years90,91. We constructed separate models for each of the response variables; maternal post-partum mass, maternal daily mass loss rate, pup daily mass gain rate, and mass transfer efficiency, and for the deviance versions of these variables. In all models, response variables were standardised by z-transformation. The deviance measures were also log-transformed to meet heteroscedasticity assumptions and address overdispersion92. All response variables were checked for normality using Q-Q plots.

Our independent variables included our estimate of resting HRV for every individual. As individuals exhibited highly repeatable resting HRV across years, we used the median RMSSD across all years present for every individual as our estimate of resting HRV in these models. This was to avoid confounding the random effect of ID, included to account for pseudoreplication, with the highly individual measures of resting HRV. Global models for each response variable also included the date on which the female gave birth (birthdate, as number of days from 1st January) as a covariate, with the sex of the pup, year and device type (Polar or Firstbeat) as factors. For all models (apart from those with maternal post-partum mass as the response variable), we included maternal post-partum mass as a covariate to account for the known positive relationship between maternal mass and daily rates of maternal mass loss and pup-growth41. All continuous covariates (resting HRV, birthdate and maternal post-partum mass) were standardised by z-transformation. Resting HRV and year were included in models as an interaction term to allow for an examination of whether different coping style fared better under different annual conditions46–48,50. For each mass response variable, the modelling procedure began by fitting the full (global) model using the Gaussian family and identity link. For model inference, we examined all plausible alternate models with reduced combinations of explanatory variables using the R function ‘dredge’ from the Package ‘MuMIn’93. The ‘best’ model was defined as the model with the lowest corrected Akaike’s information criterion (AICc). However, we also retained and examined all models within a confidence set, defined according to criteria established by Richards94. All models within a ∆AICc ≤ 6 of the ‘best’ model were retained within a preliminary confidence set. This initial confidence set was then subsetted, retaining only models with a ∆AICc value lower than more complex models within which they were nested. This approach avoids retaining overly complex models but also acknowledges that the model with the lowest AICc score is not necessarily the most parsimonious model94,95. For each response variable we also provide the output from the null model for comparison (models with no fixed effects and only the random effect).

We included no other interaction terms in the models reported here. However, where resting HRV and birthdate both featured in a confidence set, we did test alternative models with an interaction between resting HRV and birthdate, on the basis that seals with different coping styles might occupy the island at different stages of the breeding season. All these models performed worse (based on AICc) than the corresponding models lacking the interaction term, and therefore this interaction was not considered further. In all models the total number of observations was 95, and the total number of individuals was 57.

For each response variable we examined the relative contribution of ID as a random effect within the best model using r.squaredGLMM from the MuMIn package93,96 to provide conditional and marginal coefficients of determination. We also used r2beta96 to compute R2 (with 95% confidence intervals) for fixed effects within the best models.

Ethics

All animal handling procedures conformed to the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986 and were performed in collaboration with the Sea Mammal Research Unit (University of St. Andrews) operating under UK Home Office project licence #60/4009. The research presented here was approved by the Durham University Animal Welfare Ethical Review Board as well as by the University of St. Andrews Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee. Observational protocols were designed to conform to the ASAB/ABS guidelines for the treatment of animals in teaching research.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Simon Moss for his help and support in designing and improving our heart rate monitors and for facilitating our field campaigns. There are many who assisted during the five seasons of fieldwork in various ways; in particular we wish to thank; Hailey Frear, Zoe Fraser, Jodie Wells, Nathan Nwachukwu, Alec Brazier, Maddie Harris, Matt Bivins, Dr. Kimberley Bennett, Dr. Kelly Robinson, Dr. William Paterson, Izzy Langley, Hayley Quigg, and Hannah Wood. We thank the two anonymous reviewers for their very constructive and thoughtful comments. Support for the initial development and deployment of HR monitors during 2013 and 2014 field campaigns was provided to SDT by the National Geographic Society Waitt Grants Program (Grant Number W287-13). UK NERC supported long term research at the Isle of May through core funding to SMRU. PPP was in receipt of NERC grant no. NE/G008930/1 and Esmée Fairbairn Foundation funding during the work. AMB and CRS were supported by the Durham Doctoral Studentship scheme.

Author contributions

S.D.T. conceived the research, designed and coordinated the study, collected field data, carried out the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript; C.R.S., N.B. and A.M.B. participated in the design and implementation of the study, collected field data, performed behavioural data extraction, contributed advice on statistical analyses and critically revised the manuscript; PPP contributed to the design and implementation of the study, coordinated and managed the long-term study of grey seal reproductive energetics and behaviour at the Sea Mammal Research Unit, provided fitness proxy data (morphometric data), contributed advice on statistical analyses and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Data availability

Data are available in the electronic supplementary material.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-66597-3.

References

- 1.Sih A, Bell A, Johnson JC. Behavioural syndromes: an ecological and evolutionary overview. TREE. 2004;19:372–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biro PA, Stamps JA. Are animal personality traits linked to life-history productivity? TREE. 2008;23:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duckworth RA. Evolution of personality: developmental constraints on behavioural flexibility. The Auk. 2010;127:752–758. doi: 10.1525/auk.2010.127.4.752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf M, Weissing FJ. An explanatory framework for adaptive personality differences. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2010;365:3959–3968. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carere, C. & Maestripieri, D. editors. 2013. Animal personalities. Behavior, physiology, and evolution. Chicago (IL): The University of Chicago Press.

- 6.Dochtermann NA, Dingemanse NJ. Behavioral syndromes as evolutionary constraints. Behav. Ecol. 2013;24:806–811. doi: 10.1093/beheco/art002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Réale D, Gallant BY, Leblanc M, Festa-Bianchet M. Consistency of temperament in bighorn ewes and correlates with behaviour and life history. Anim. Behav. 2000;60:589–597. doi: 10.1006/anbe.2000.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adriaenssens B, Johnsson JI. Shy trout grow faster: exploring links between personality and fitness-related traits in the wild. Behav. Ecol. 2011;22:135–143. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arq185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith BR, Blumstein DT. Fitness consequences of personality: A metaanalysis. Behav. Ecol. 2008;19:448–455. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arm144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dingemanse NJ, Both C, Drent PJ, Tinbergen JM. Fitness consequences of avian personalities in a fluctuating environment. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2004;271:847–852. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Both C, Dingemanse NJ, Drent PJ, Tinbergen JM. Pairs of extreme avian personalities have highest reproductive success. J. Anim. Ecol. 2005;74:667–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2005.00962.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monestier C, et al. Is a proactive mum a good mum? A mother’s coping style influences early fawn survival in roe deer. Behav. Ecol. 2015;26:1395–1403. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arv087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.May TM, Page MJ, Fleming PA. Predicting survivors: animal temperament and translocation. Behav. Ecol. 2016;27:969–977. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arv242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Archard GA, Braithwaite VA. The importance of wild populations in studies of animal temperament. J. Zool. 2010;281:149–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00714.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrari C, et al. Testing for the presence of coping styles in a wild mammal. Anim. Behav. 2013;85:1385–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.03.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herborn KA, et al. Personality in captivity reflects personality in the wild. Anim. Behav. 2010;79:835–843. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.12.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Twiss SD, Cairns C, Culloch RM, Richards SA, Pomeroy PP. Variation in female grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) reproductive performance correlates to proactive-reactive behavioural types. Plos One. 2012;7:e49598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blaszczyk MB. Boldness towards novel objects predicts predator inspection in wild vervet monkeys. Anim. Behav. 2017;123:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2016.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward‐Fear G, et al. The ecological and life history correlates of boldness in free‐ranging lizards. Ecosphere. 2018;9:e02125. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.2125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeRango EJ, et al. Intrinsic and maternal traits influence personality during early life in Galápagos sea lion (Zalophus wollebaeki) pups. Anim. Behav. 2019;154:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2019.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benson-Amram S, Holekamp KE. Innovative problem solving by wild spotted hyenas. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2012;279:4087–4095. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter AJ, Marshall HH, Heinsohn R, Cowlishaw G. How not to measure boldness: novel object and antipredator responses are not the same in wild baboons. Anim. Behav. 2012;84:603–609. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arvidsson LA, Adriaensen F, van Dongen S, De Stobbeleere N, Matthysen E. Exploration behaviour in a different light: testing cross-context consistency of a common personality trait. Anim. Behav. 2017;123:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2016.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuen CH, Schoepf I, Schradin C, Pillay N. Boldness: are open field and startle tests measuring the same personality trait? Anim. Behav. 2017;128:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2017.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sih A, Cote J, Evans M, Fogarty S, Pruitt J. Ecological implications of behavioural syndromes. Ecol. Letts. 2012;15:278–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Réale D, Reader SM, Sol D, McDougall PT, Dingemanse NJ. Integrating animal temperament within ecology and evolution. Biol. Rev. 2007;82:291–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolf M, Weissing FJ. Animal personalities: consequences for ecology and evolution. TREE. 2012;27:452–461. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sgoifo A, et al. Incidence of arrhythmias and heart rate variability in wild-type rats exposed to social stress. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:1754–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.4.H1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koolhaas JM, et al. Coping styles in animals: current status in behavior and stress physiology. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1999;23:925–935. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(99)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koolhaas JM, De Boer SF, Coppens CM, Buwalda B. Neuroendocrinology of coping styles: Towards understanding the biology of individual variation. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2010;31:307–321. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Visser EK, et al. Heart rate and heart rate variability during a novel object test and a handling test in young horses. Physiol. Behav. 2002;76:289–296. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(02)00698-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Borell E, et al. Heart rate variability as a measure of autonomic regulation of cardiac activity for assessing stress and welfare in farm animals: a review. Physiol. Behav. 2007;92:293–316. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jonckheer-Sheehy VSM, Vinke CM, Ortolani A. Validation of a Polar® human heart rate monitor for measuring heart rate and heart rate variability in adult dogs under stationary conditions. J. Vet. Behav. 2012;7:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2011.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Øverli Ø, et al. Evolutionary background for stress-coping styles: relationships between physiological, behavioral, and cognitive traits in non-mammalian vertebrates. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2007;31:396–412. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rödel HG, Monclús R, von Holst D. Behavioral styles in European rabbits: social interactions and responses to experimental stressors. Physiol. Behav. 2006;89:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bubac CM, et al. Repeatability and reproductive consequences of boldness in female gray seals. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2018;72:100. doi: 10.1007/s00265-018-2515-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shuert, C. R., Pomeroy, P. P. & Twiss, S. D. In press. Coping styles in capital breeders modulate behavioural trade-offs in time allocation: assessing fine-scale activity budgets in lactating grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) using accelerometry and heart rate variability. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 74, 8, 10.1007/s00265-019-2783-8.

- 38.Carere C, Caramaschi D, Fawcett TW. Covariation between personalities and individual differences in coping with stress: Converging evidence and hypotheses. Curr. Zool. 2010;56:728–740. doi: 10.1093/czoolo/56.6.728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coppens CM, de Boer SF, Koolhaas JM. Coping styles and behavioural flexibility: Towards underlying mechanisms. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2010;365:4021–4028. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kontiainen P, et al. Aggressive Ural owl mothers recruit more offspring. Behav. Ecol. 2009;20:789–796. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arp062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pomeroy PP, Fedak MA, Rothery P, Anderson S. Consequences of maternal size for reproductive expenditure and pupping success of grey seals at North Rona, Scotland. J. Anim. Ecol. 1999;68:235–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2656.1999.00281.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santicchia F, et al. Habitat-dependent effects of personality on survival and reproduction in red squirrels. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2018;72:134. doi: 10.1007/s00265-018-2546-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruiz-Gomez M, et al. Response to environmental change in rainbow trout selected for divergent stress coping styles. Physiology and Behavior. 2011;102:317–22. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boness DJ, Anderson SS, Cox CR. Functions of female aggression during the pupping and mating season of grey seals, Halichoerus grypus (Fabricius) Can. J Zool. 1982;60:2270–2278. doi: 10.1139/z82-293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson SS, Harwood J. Time budgets and topography – how energy reserves and terrain determine the breeding behaviour of grey seals. Anim. Behav. 1985;33:1343–1348. doi: 10.1016/S0003-3472(85)80196-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Twiss SD, Caudron A, Pomeroy PP, Thomas CJ, Mills JP. Finescale topographical correlates of behavioural investment in offspring by female grey seals, Halichoerus grypus. Anim. Behav. 2000;59:327–338. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Redman P, Pomeroy PP, Twiss SD. Grey seal maternal attendance patterns are affected by water availability on North Rona, Scotland. Can. J. Zool. 2001;79:1073–1079. doi: 10.1139/z01-081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Twiss SD, Thomas CJ, Poland VF, Graves JA, Pomeroy PP. The impact of climatic variation on the opportunity for sexual selection. Biol. Letts. 2007;3:12–15. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stephenson CM, Matthiopoulos J, Harwood J. Influence of the physical environment and conspecific aggression on the spatial arrangement of breeding grey seals. Ecol. Inform. 2007;2:308–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2007.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stewart JE, Pomeroy PP, Duck CD, Twiss SD. Finescale ecological niche modeling provides evidence that lactating gray seals (Halichoerus grypus) prefer access to fresh water in order to drink. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2014;30:1456–72. doi: 10.1111/mms.12126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pomeroy PP, Anderson SS, Twiss SD, McConnell BJ. Dispersion and site fidelity of breeding female grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) on North Rona, Scotland. J. Zool. 1994;233:429–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1994.tb05275.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bijleveld AI, et al. Personality drives physiological adjustments and is not related to survival. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2014;281:20133135. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Witt TJ, Sih A, Wilson DS. Costs and limits of phenotypic plasticity. TREE. 1998;13:77–91. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(97)01274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruiz-Gomez MDEL, et al. Behavioral plasticity in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) with divergent coping styles: When doves become hawks. Hormones and Behavior. 2008;54:534–538. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hulme, M. et al. Climate Change Scenarios for the United Kingdom: The UKCIP02 Scientific Report, Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK. 120pp (2002).

- 56.Post, E S. & Mann, M. Acceleration of phenological advance and warming with latitude over the past century. Sci. Rep. 8, 10.1038/s41598-018-22258-0 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Bolnick DI, et al. The Ecology of Individuals: Incidence and Implications of Individual Specialization. Am.Nat. 2003;161:1–28. doi: 10.1086/343878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Violle C, et al. The return of the variance: intraspecific variability in community ecology. TREE. 2012;27:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carrete M, Tella JL. Inter-Individual Variability in Fear of Humans and Relative Brain Size of the Species Are Related to Contemporary Urban Invasion in Birds. Plos One. 2011;6:e18859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zidar J, et al. A comparison of animal personality and coping styles in the red junglefowl. Anim. Behav. 2017;130:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2017.06.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dingemanse NJ, Kazem AJN, Réale D, Wright J. Behavioural reaction norms: Animal personality meets individual plasticity. TREE. 2010;25:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Twiss SD, Poland VF, Graves JA, Pomeroy PP. Finding fathers: Spatio-temporal analysis of paternity assignment in grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) Mol. Ecol. 2006;15:1939–1953. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smout S, King R, Pomeroy P. Environment‐sensitive mass changes influence breeding frequency in a capital breeding marine top predator. J. Anim. Ecol. 2019;00:1–13. doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.13128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hiby L, et al. Analysis of photo‐id data allowing for missed matches and individuals identified from opposite sides. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013;4:252–259. doi: 10.1111/2041-210x.12008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bennett KA, Speakman JR, Moss SEW, Pomeroy PP, Fedak MA. Effects of mass and body composition on fasting fuel utilisation in grey seal pups (Halichoerus grypus Fabricius): an experimental study using supplementary feeding. J. Exp. Biol. 2007;210:3043–3053. doi: 10.1242/jeb.009381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Langton SD, Moss SE, Pomeroy PP, Borer KE. Effect of induction dose, lactation stage and body condition on tiletamine-zolazepam anaesthesia in adult female grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) under field conditions. Vet. Rec. 2011;168:457. doi: 10.1136/vr.d1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marchant-Forde RM, Marlin DJ, Marchant-Forde JN. Validation of a cardiac monitor for measuring heart rate variability in adult female pigs: accuracy, artefacts and editing. Physiol. Behav. 2004;80:449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hopster H, Blokhuis HK. Validation of a heart-rate response monitor for measuring a stress response in dairy cows. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 1994;74:465–474. doi: 10.4141/cjas94-066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Parker M, Goodwin D, Eager RA, Redhead ES, Marlin DJ. Comparison of Polar® heart rate interval data with simultaneously recorded ECG signals in horses. Comp. Exercise Physiol. 2010;6:137–142. doi: 10.1017/S1755254010000024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ille N, Erber R, Aurich C, Aurich J. Comparison of heart rate and heart rate variability obtained by heart rate monitors and simultaneously recorded electrocardiogram signals in nonexercising horses. J. Vet. Behav. 2014;9:341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2014.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Essner A, et al. Comparison of Polar® RS800CX heart rate monitor and electrocardiogram for measuring inter-beat intervals in healthy dogs. Physiol. Behav. 2015;138:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brannan, N. B. L. Investigating the physiological underpinnings of proactive and reactive behavioural types in grey seals (Halichoerus grypus): Trial deployment of a minimally invasive data logger for recording heart rate and heart rate variability in a wild free-ranging breeding pinniped species, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online, http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11980/ (2017).

- 73.Berntson GG, et al. Heart rate variability: Origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:623–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saalasti, S., Seppänen, M. & Kuusela, A. Artefact correction for heart beat interval data. In: Advanced Methods for Processing Bioelectrical Signals; 1st Probisi 2004 Proceedings. Jyväskylä, Finland: University of Jyväskylä (2004).

- 75.Martínez, C. A. G. et al. Heart Rate Variability Analysis with the R Package RHRV, Springer (2017).

- 76.Penttila J, Helminen A, Jartti T, Kuusela T. Time domain, geometrical and frequency domain analysis of cardiac vagal outflow: effects of various respiratory patterns. Clin. Physiol. 2001;21:365–376. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.2001.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pohlin F, et al. Seasonal variations in heart rate variability as an indicator of stress in free-ranging pregnant Przewalski’s horses (E. ferus przewalskii) within the Hortobágy National Park in Hungary. Front. Physiol. 2017;8:664. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Altmann J. Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behav. 1974;49:227–267. doi: 10.1163/156853974X00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shuert CR, Pomeroy PP, Twiss SD. Assessing the utility and limitations of accelerometers and machine learning approaches in classifying behaviour during lactation in a phocid seal. Anim. Biotelem. 2018;6:14. doi: 10.1186/s40317-018-0158-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kovacs KM, Lavigne D. Growth of grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) neonates: Differential maternal investment in the sexes. Can. J. Zool. 1986;64:1937–1943. doi: 10.1139/z86-291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kovacs KM. Maternal behaviour and early behavioural ontogeny of grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) on the Isle of May, UK. J. Zool. 1987;213:697–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1987.tb03735.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Anderson SS, Fedak MA. Grey seal, Halichoerus grypus, energetics: females invest more in male offspring. J. Zool. 1987;211:667–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1987.tb04478.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Haller MA, Kovacs K, Hammill MO. Maternal behaviour and energy investment by grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) breeding on land-fast ice. Can. J. Zool. 1996;74:1531–1541. doi: 10.1139/z96-167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mellish JAE, Iverson SJ, Bowen WD. Variation in milk production and lactation performance in grey seals and consequences for pup growth and weaning characteristics. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 1999;72:677–90. doi: 10.1086/316708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.R Core Team. 2018. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.R-project.org/.

- 86.Bell AM, Hankison SJ, Laskowski KL. The repeatability of behaviour: A meta-analysis. Anim. Behav. 2009;77:771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H. Repeatability for Gaussian and non-Gaussian data: A practical guide for biologists. Biol. Rev. 2010;85:935–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stoffel MA, Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H. rptR: Repeatability estimation and variance decomposition by generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2017;8:1639–1644. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015;67:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bolker BM, et al. Generalized linear mixed models: a practical guide for ecology and evolution. TREE. 2009;24:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dingemanse NJ, Dochtermann NA. Quantifying individual variation in behaviour: Mixed-effect modelling approaches. J. Anim. Ecol. 2013;82:39–54. doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Elphick CS. A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010;1:3–14. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2009.00001.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bartón, K. MuMIn: multi-model inference. R package version 1.10.0. 2014. Available online at, http://cran.r-project.org/package=MuMIn (2014).

- 94.Richards SA. Dealing with overdispersed count data in applied ecology. J. Appl. Ecol. 2008;45:218–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01377.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Richards SA, Whittingham MJ, Stephens PA. Model selection and model averaging in behavioural ecology: the utility of the IT-AIC framework. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2011;65:77–89. doi: 10.1007/s00265-010-1035-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H. A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013;4:133–142. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00261.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in the electronic supplementary material.