Abstract

Paediatric sarcomas are a heterogeneous group of disorders constituting bone sarcoma and various soft tissue sarcomas. Almost one-third of these presents with metastasis at baseline and another one-third recur after initial curative treatment. There is a huge unmet need in this cohort in terms of curative options and/or prolongation of survival. In this review, we have discussed the current treatment options, challenges and future strategies of managing relapsed/refractory paediatric sarcomas. Upfront risk-adapted treatment with multidisciplinary management remains the main strategy to prevent future recurrence or relapse of the disease. In the case of limited local and/or systemic relapse or late relapse, initial multimodality management can be administered. In treatment-refractory cases or where cure is not feasible, the treatment options are limited to novel therapeutics, immunotherapeutic approach, targeted therapies, and metronomic therapies. A better understanding of disease biology, mechanism of treatment refractoriness, identifications of driver mutation, the discovery of novel targeted therapies, cellular vaccine and adapted therapies should be explored in relapsed/refractory cases. Close national and international collaboration for translation research is needed to fulfil the unmet need.

Keywords: paediatric sarcoma, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, relapsed sarcoma, osteosarcoma, disease biology

Introduction

Paediatric sarcoma constitutes a major group of disease that includes osteosarcoma (OGS), Ewing’s sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor (EWS/PNET), rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), and heterogeneous group of soft tissue sarcoma (STS), mostly infantile fibrosarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour (MPNST), termed as non-rhabdomyomatous soft tissue sarcoma (NRSTS). With the introduction of multimodality treatment including poly-chemotherapy, surgery and/or radiotherapy, the outcome of localized paediatric sarcoma has improved drastically. However, 20–30% localized sarcoma recurs where cure seldom occurs. On the other hand, a sizeable number of bone1 and soft tissue sarcoma2 presents with metastasis at baseline, and the cure rate is still low with the current armamentarium of systemic anti-cancer therapies. In spite of progress in chemotherapeutic combinations, newer surgical approach and radiation techniques, local as well as distant recurrence is one of the major challenges in the management of paediatric sarcomas. The outcome remains dismal in recurrent or treatment-refractory (primary or secondary) setting with the currently available systemic therapies even with a better understanding of tumorigenesis and discovery of potential therapeutic targets.

In-depth understanding of disease biology, determination of molecular signature, identifications of potentially targetable driver mutation, newer immunotherapeutic approach, risk-adapted treatment strategies, and long-term maintenance therapy remains the optimal approach to treat recurrent and refractory paediatric sarcomas.

In this review, we have discussed the current standard of care in recurrent bone sarcoma & STS in paediatric & young adult patients with emerging therapeutic options, unmet needs and future strategies.

Burden of Problems

Data regarding burden of refractory paediatric sarcoma can be estimated from the patients where cure is not possible as literature regarding the same is limited. There is no consensus regarding optimal treatment in second line as various regimens have been tried and there is no head-to-head comparison amongst the different regimens.

Survival in OGS has plateaued at 70% after the dramatic improvement in the 1980s and 1990s.3 In a large retrospective analysis of 1067 patients, there were 564 (52.85%) recurrences with a median time of 13 months. Post recurrence survival was 18% at 5 years. Approximately 35% had refractory disease.4

For localized EWS, the 5-year overall survival ranges from 65% to 75% whereas in metastatic setting it is less than 30%, except in isolated pulmonary metastasis (approximately 50%).5 The 5-year survival of relapsed EWS is 13%. Patients who relapse in the first 2 years from diagnosis have a 5-year survival of 7% compared to 29% who relapse after 2 years from diagnosis.6 At present, there is no standard protocol to treat relapsed EWS due to paucity of clinical trials.7

In pediatric populations, the most common soft tissue sarcoma is RMS, which accounts for one-half of all soft tissue sarcomas. Relapses occur in around 30% cases of RMS, with most relapses occurring before 2 years after initial diagnosis whereas late relapses (after 5 years of diagnosis) are rare and constitute less than 10% of relapsed cases. Most relapses (80%) occur at distant site and involve lungs, bones or bone marrow. Few patients (20%) relapse at the local site and have a more favourable prognosis.8–11 Prognostic factors associated with recurrent or progressive disease include factors at the time of initial diagnosis, including histological subtype, disease group, stage, age 10 years or younger, size, site, and lack of initial radiation therapy. Distant site of recurrence and time of relapse after diagnosis <18 months are important prognostic factors for survival at the time of relapse.8–10,12

In a retrospective analysis by Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group (IRSG), 605 (25.6%) patients out of 2364 treated on IRS-III, IRS-IV pilot, & IRS-IV experienced disease relapse or progression. Median OS was 9.6 months and 17% of patients survived till 5 years after relapse. Probability of survival after relapse was dependent on histologic subtype, disease group, and stage at initial diagnosis. At the time of relapse distant site recurrence have poor survival compared with local recurrence.8

Of 1398 patients with localized disease at diagnosis treated in International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) Malignant Mesenchymal Tumour/MMT 84, 89, and 95 studies, 474 (33.9%) had a relapse. Metastatic disease at relapse, prior treatment, initial tumour size >5 cm, and relapse within 18 months of diagnosis were associated with poor outcomes.10 Many other retrospective analyses have found similar prognostic factors for survival.12

NRSTS accounts for approximately 50% of paediatric STS (13). It is a heterogenous group of rare tumours, with common histologies being synovial cell sarcoma, infantile fibrosarcoma and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour. Five-year survival from synovial sarcoma has been approximately 77%.13 Survival of infantile fibrosarcoma ranges from 80% to 94%.14,15 Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour is relatively chemoresistant. The five-year survival has ranged from 23% to 69%.13

Pathophysiology of Treatment Refractoriness

Pathophysiology of treatment refractoriness is an evolving area of research and there are a lot of knowledge gaps. The studies have focussed on cancer stem cells (CSC), signalling pathways and multidrug resistance. OGS treatment refractoriness has been relatively well studied compared to others.

Gibbs et al16 demonstrated CSC in OGS which has the ability to self-renew, form sarcospheres and were multipotent. These cells had high expression of CD 133, CD 117 and Stro-1.17,18 In vitro studies in OGS cell lines and xenograft mouse model has shown that exposure to chemotherapy transforms a subpopulation of OGS cells to CSC like phenotype.19 These transformed cells have increased the capacity to form sarcospheres in vitro and initiation of tumour in vivo.20 These transformed cells are chemoresistant and are found in refractory OGS.21

It is thought that Wnt-β-catenin signalling pathway plays a key role in the development of OGS and chemotherapy resistance. Increased cytoplasmic expression β-catenin predicts lung metastasis in murine OGS cell line.22 Small interfering RNA (siRNA) mediated silencing of β-catenin leads to chemoresistance to doxorubicin mediated by N-kappaB, inhibition of invasion and motility in human OGS cell line.23 Increased expression of TWIST decreases β-catenin via PI3K pathway leading to cisplatin sensitivity in vitro.24 Knocking down of β-catenin results in methotrexate sensitivity in OGS cell line.25 Apart from Wnt-β-catenin pathway, Hedgehog pathway, Notch, MAP kinase and FGF signalling pathway play a role in maintaining OGS CSC.26

Multidrug resistance in OGS is mediated through different mechanisms. ATP-binding cassette transporters play a key role in drug uptake and transport. Intracellular concentration of the drug is decreased by P-glycoprotein (P-gp), a membrane efflux pump.

P-gp is associated with multidrug resistance in OGS cell lines.27 High P-gp levels have been associated with poor event-free survival and increase the risk of adverse events.28 P-gp has a potential to be used as a biomarker for risk stratification in OGS. Polymorphisms in multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 have been associated with necrosis, methotrexate resistance, myelosuppression and cardiotoxicity.29

Methotrexate is one of the key drugs in OGS and it enters into cells through reduced folate carrier (RFC). Reduced RFC expression is associated with poor histologic response.30,31 Low levels of DNA topoisomerase II β are associated with multidrug resistance in OGS cell line.31 Human glutathione S-transferase P1 (GSTP1) overexpression is associated with poor histological response and prognosis, as it metabolizes chemotherapeutic agents.32,33 There is evidence to suggest that OGS cells develop resistance due to the ability to repair the DNA damaged by cisplatin. Excision repair cross-complementing (ERCC) polymorphisms were associated with event-free survival (EFS) in OGS patients.34–36 In a meta-analysis of 858 OGS patients, ERCC2 polymorphism Lys751Gln was associated with OS and His46His mutation was associated with EFS.36 A key enzyme in the base excision repair pathway (repairs DNA damage) is Apurinic/apyrimidinic exonuclease 1 (APEX 1). Increased expression of APEX 1 is associated with decreased disease-free survival and increased tumour recurrence.37 MicroRNAs modulate OGS drug resistance via DNA damage repair, apoptosis avoidance, suppression of autophagy, activation of cancer stem cells and alteration of OGS associated signal pathways.38

EWS therapy resistance is explained on the basis of CSC, drug-metabolizing enzymes and modulation of signalling pathways. It is thought that EWSCSC arises from primitive mesenchymal stem cells.39 The proposed explanations for chemoresistance of EWS CSC are that they are quiescent, have enhanced ability to repair DNA damage, disrupted apoptotic pathways and high expression of drug-efflux proteins.40 Glutathione S transferases (GST) which belong to the family of Phase II detoxification enzymes are involved in the metabolism of toxic compounds. Low expression of microsomal GST was associated with better prognosis and is correlated with sensitivity to doxorubicin. The same group identified molecular signatures using microarray technology which predicted tumour resistance.41 ERBB4 tyrosine kinase is overexpressed in EWS cell line of chemoresistant and metastatic patients. Overexpression of ERBB4 correlates with poor disease-free survival.42 STAG2 overexpression is associated with metastaticEWS.43 Tumour heterogeneity in tumour cells and microenvironment has also been implicated in chemoresistant EWS.40

Constitutional activation of STAT3 causes resistance to chemotherapy in RMS cell lines.44 In a study that included 31 patients of RMS and 12 patients of NRSTS, biopsy was done at baseline from the primary lesion and from the residual tumour at the end of treatment. The paired samples were analysed for P-gp, multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP 1) and multidrug resistance 3 (MDR 3). Expression of MRP1, MDR 3 and P-gp was higher than in post-treatment specimens suggesting their role in chemoresistance. Clonal selection of MDR protein-expressing tumour cells and up-regulation of MDR proteins were thought to be the possible explanations for increased expression of MDR proteins in post-treatment specimens.45 Serum and glucocorticoid inducible kinase expression in RMS has been shown to be associated with treatment resistance in RMS cell lines.46 In vitro and in vivo studies in RMS have shown that GST mediates chemotherapy resistance.47

Genomic Profiling, Next-Generation Sequencing and Target-Based Approach

Whole genome sequencing was done in 100 patients of OGS with outcome of relapse, percent tumour necrosis and survival. Intronic and intergenic hotspot regions from 26 genes were identified which were associated with relapse. Mutations in genes belonging to AKR enzyme family, PI3K pathways, cell-cell adhesion processes and variants of SLC22 were associated with tumour necrosis and survival.48 In whole-exome analysis of eight OGS patients, out of which three were nonresponder fifteen genes were identified which are possibly associated with drug resistance, metastasis and can be drug targets.49 In a case, a series of two metastatic and chemo-refractory OGS patients comprehensive molecular profiling was done and molecular targeted therapy was given accordingly. Both the patients did not benefit from the approach.50 Whole exome sequencing, whole transcriptome sequencing, high-density single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis of the tumor and whole exome sequencing of matched germline DNA was done in 59 relapse/refractory paediatric solid tumours to evaluate genome-guided therapy. Out of 59 patients, ten patients were refractory sarcoma [EWS-5, RMS-2, inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma-2 and OGS-1]. Actionable mutation with FDA (Unites States Food and Drug Administration) approved drug in adults was seen in four patients while for drugs currently in paediatric trial was seen in five patients. The study showed that multi-dimensional “omics” approach is feasible and can have therapeutic implications.51

The Individualized Therapy for Relapsed Malignancies in Childhood (INFORM) studied 57 patients of relapse paediatric tumours and whole-exome, low-coverage, whole-genome, RNA sequencing, methylation and expression microarray analysis was done. Out of these 57 patients, ten patients of EWS, 5 patients with RMS, 5 patients of OGS and NRSTSwere 3 which were analysable. Eight out of 23 patients had targetable alterations with intermediate or higher prioritization scores.52

In a study of 62 patients with relapsed/refractory paediatric tumours, whole exome sequencing and RNA sequencing were done. Thirteen patients had sarcoma [OGS-7, RMS-4 and EWS-2]. All patients had potentially actionable alterations, which were grouped into targeted therapy, biomarker, risk stratification and diagnostic. Ten patients had actionable alterations for targeted therapy out of which two patients received targeted therapy.53

Comprehensive genomic profiling of 102 advanced/relapse/refractory sarcoma patients were done which included OGS (10), RMS (6) and EWS (3) and actionable mutations were seen in six patients.54 Twenty refractory paediatric sarcoma patients were evaluated for targetable aberrations by array-based expression profiling. All patients had actionable targets. Nine patients received therapy based on actionable alteration and eleven patients did not receive. Median OS and PFS were 8.83 and 6.17 months in the targeted treatment group compared to 4.9 months and 1.7 months in the group which did not receive the targeted therapy, with p values of 0.0014 and 0.0011, respectively. This study showed that patients treated with therapy targeting genetic alterations are likely to benefit.55

In a study of 71 OGS samples from 66 adults and paediatric patients, next-generation sequencing (NGS) was used to identify potentially actionable mutations. Out of these 71 samples, 32 were from metastatic or recurrent lesions. In metastatic/recurrent samples 41.2% had VEGFA whereas the primary site had only 9.7%.56 Amplification of VEGFA has been shown to be a predictor of poor outcomes.57 In the whole cohort, they found genetic changes that can be potentially targeted in 21% and in another 40% they found mutually exclusive VEGFA or PDGFR amplification which can be evaluated as targets. The authors proposed a genetic algorithm classifying approximately 50% of OGS patients eligible for targeted therapy trials.56

Despite encouraging results in identification of targets in refractory paediatric sarcoma, genomic profiling and next-generation sequencing approaches are still experimental.

Current Therapeutic Options in Selected Relapsed/Refractory Paediatric Sarcomas

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Treatment at the time of relapse depends on many factors, viz. site of recurrence, previous treatment received, and individual patient preference. There are no clear guidelines for the treatment of relapsed RMS. Treatment of recurrent childhood RMS should include multimodality options including chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy whenever feasible as summarized in Table 4. In the case of localized disease where surgery is possible, initial surgical resection should be attempted followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy. If the initial disease is unresectable, initial chemotherapy followed by local therapy, ie, surgery or radiotherapy should be done. Surgery may also be attempted in patients with fewer lung metastases. Radiotherapy is an important modality in recurrent RMS, especially in cases where a patient has not received prior radiotherapy and if surgical excision is not feasible.58–60 In the case of gross metastatic disease, palliative chemotherapy may be administered based on chemotherapeutic agents received at the time of initial diagnosis.

Table 4.

Summary of Treatment of Relapsed Paediatric Sarcomas

| Disease Site and Extent | Resectability | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | ||

| Localized or few metastasis |

Resectable | Surgery → chemotherapy ± radiotherapy |

| Unresectable | Chemotherapy → surgery or/+ radiotherapy | |

| Multiple metastasis | Unresectable | Previously received 2 drug (VCR + Act D) → VAC regimen |

| Previously received 3 drug VAC regimen → ICE or VCR + Irinotecan ± Temozolomide | ||

| Osteosarcoma | ||

| Localized or few metastasis |

Resectable | Surgery → chemotherapy ± radiotherapy |

| Unresectable | Palliative chemotherapy (high dose Ifosfamide based) or regorafenib | |

| Lung metastasis | Resectable | Surgery → chemotherapy ± radiotherapy |

| Unresectable | Palliative chemotherapy (high dose Ifosfamide based) or regorafenib | |

| Painful bony metastasis | Unresectable | Sm 153 EDTMP or Ra 223 |

| Multiple metastasis | Unresectable | Palliative chemotherapy (high dose Ifosfamide based) or regorafenib |

| Ewing sarcoma | ||

| Localized or few metastasis |

Resectable | Surgery → chemotherapy ± radiotherapy |

| Unresectable | Chemotherapy → surgery or radiotherapy | |

| Multiple metastasis | Unresectable | Palliative chemotherapy (ICE or Irinotecan + Temozolomide ± VCR) |

| Infantile fibrosarcoma | ||

| Localized | Resectable | Surgery → chemotherapy ± radiotherapy |

| Multiple metastasis | Unresectable | Palliative NTRK inhibitors viz. Larotrectinib |

Abbreviations: Act D, actinomycin D; ICE, ifosfamide/carboplatin/etoposide; NTRK, neurotrophic tropomyosin receptor kinase; VAC, vincristine/actinomycin D/cyclophosphamide; VCR, vincristine.

Chemotherapy has an important role in the treatment of relapsed RMS. However, there is no clear data for the choice of chemotherapy due to lack of comparative trials and heterogeneity of the trial population. Patients should be encouraged to enrol in clinical trials if available. If the patient has previously received two drug VA (vincristine and actinomycin D) therapy, full course of VAC (vincristine, actinomycin D and cyclophosphamide) may be administered at relapse. Patients who have received VAC, options include Ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (ICE); cyclophosphamide/topotecan; irinotecan, temozolomide, vincristine; gemcitabine, docetaxel; vinorelbine; temsirolimus; and combination of above agents. Various regimens are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Various Chemotherapy Options in Relapsed RMS

| Author | Year | Study Nature | Number (n) | Chemotherapy | ORR (%) | CR/PR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kung et al61 | 1995 | I/II | 14 | ICE | 43 | 3/3 |

| Klingebiel et al174 | 1998 | II | 30 | ICE | 33 | 7/3 |

| Van Winkle et al62 | 2005 | I/II | 27 | ICE | 66 | 9/9 |

| Saylors et al120 | 2001 | II | 15 | Cyclophosphamide/Topotecan | 66 | 0/10 |

| Compostella et al64 | 2019 | II | 38 | Cyclophosphamide/Topotecan/Carboplatin/Etoposide | 28 | 2/7 |

| Mascarenhas et al65 | 2010 | II (window) | 45 | Vincristine/Irinotecan | 26 | NA |

| 47 | Vincristine/Irinotecan | 37 | ||||

| Defachelles et al175 | 2019 | II | 60 | Vincristine/Irinotecan/Temozolomide | 44 | NA |

| 60 | Vincristine/Irinotecan | 31 | ||||

| Setty et al176 | 2018 | R | 15 | Vincristine/Irinotecan/Temozolomide | 0 | 0/0 |

| Kuttesch et al177 | 2009 | II | 11 | Vinorelbine | 35 | 1/3 |

| Casanova et al178 | 2002 | R | 12 | Vinorelbine | 50 | 0/6 |

| Casanova et al179 | 2004 | I/II | 17 | Vinorelbine/Cyclophosphamide | 36 | 1/6 |

| Minard-Colin et al180 | 2012 | II | 50 | Vinorelbine/Cyclophosphamide | 36 | 4/14 |

| Mascarenhas et al181 | 2014 | II | 87 | Vinorelbine/Cyclophosphamide/Temsirolimus | 26 | 5/6 |

| Vinorelbine/Cyclophosphamide/Bevacizumab | 37 | 0/17 | ||||

| Rapkin et al182 | 2012 | R | 5 | Gemcitabine/Docetaxel | 40 | 1/1 |

Abbreviations: ORR, overall response rate; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission; ICE, ifosfamide/carboplatin/etoposide; R, retrospective.

Ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (ICE) has been commonly used regimen in the past, but has significant hematologic toxicity. In a prospective trial of 92 patients with relapsed solid tumours including 14 relapsed RMS, responses were seen in 43% of patients.61 In Children’s Cancer group pooled analysis of three phase I/II trials using ICE in 27 relapsed/refractory RMS patients, the response was observed in two-third of patients.62

Cyclophosphamide/topotecan has been tested in some phase II trials. In one study 10 out of 15 RMS patients responded, however, all patients had partial response.63 In an Italian study, topotecan/cyclophosphamide was combined with carboplatin/etoposide in 38 patients with recurrent or refractory RMS. Response was seen in around one-third of patients but the 5-year OS (17%) and PFS (14%) rates were poor. Rates of haematological toxicity were high.64

Vincristine and irinotecan with/without other drugs are the most commonly used regimens in the current era due to good response rates and manageable toxicity. However, gastrointestinal toxicity and neuropathy remain of concern. A Children’s Oncology Group (COG) prospective, randomized trial (COG-ARST0121) showed no significant difference between responses in two schedules of vincristine/irinotecan.65 In a European Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group (EpSSG) study, 120 patients with recurrent or refractory RMS were randomized to vincristine and irinotecan (VI) or vincristine, irinotecan, and temozolomide (VIT). The VIT arm was associated with higher response rates and better survival.66

High dose chemotherapy (HDT) followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHSCT) has also been tried for patients with RMS in relapse as well as upfront setting. However, available data did not show a significant benefit with this approach.67,68

PAX-FOXO1 fusion protein is expressed in tumor cells in RMS has been historically difficult to target. Novel approaches are currently being developed designed to target either PAX-FOXO1 or its co-regulators. Experimental approach using nanoparticles as a vehicle to transport siRNA to downregulate PAX-FOXO1 has been demonstrated in vitro studies.69 Cell line studies have shown that targeting BET bromodomain protein BRD4 which is a coregulator of PAX-FOXO1 by JQ1 inhibits PAX-FOXO1 function.70 Similarly, targeting chromatin helix DNA binding protein 4 (CHD4) which acts as a coregulator of PAX-FOXO1is feasible in preclinical models.71 Potential targets in receptor tyrosine kinase are IGF-1R, FGFR4, PDGFR, ALK, MET, VEGFR and ERBB2. NOTCH and Smo are being evaluated as the target in developmental pathways.72

Various trials involving nivolumab (NCT02304458), pembrolizumab (NCT02332668), IGF-1 inhibitors (NCT03041701), Wee1 inhibitor (NCT02095132) and CDK4 inhibitors (NCT03709680) are currently undergoing. The summary of the current ongoing clinical trials involving novel therapeutic approaches to RMS is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Ongoing Studies in Relapsed/Refractory Paediatric Sarcoma

| Clinical Trial Identifier | Name of Agent | Disease | Phase | Population | Primary Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT02304458 | Nivolumab ± Ipilimumab | Multiple solid tumours | I/II | 1–18 years | Objective response rate |

| NCT02332668 | Pembrolizumab | Relapsed or refractory solid tumours | II | 6 months to 18 years | Objective response rate |

| NCT03041701 | Ganitumab (anti- IGF1R) + Dasatinib (SRC inhibitor) | Relapsed or refractory rhabdomyosarcoma | I/II | No age limit | Objective response rate |

| NCT03709680 |

|

Relapsed or refractory pediatric sarcomas | I/II | 2–21 years | Objective response rate |

| NCT02095132 | Adavosertib (WEE1 Inhibitor) + Irinotecan | Relapsed or refractory pediatric tumours | I/II | 1–16 years | Maximal tolerable dose/toxicity |

| NCT02484443 | Dinutuximab (Anti GD2) + Sargramostim | Recurrent osteosarcoma | II | Up to 16 years | Disease control rate |

| NCT02470091 | Denosumab (RANKL inhibitor) | Osteosarcoma | II | 11–50 years | Disease control rate |

| NCT03155620 | Targeted Therapy Directed by Genetic Testing | Relapsed or refractory solid tumours | II | 1–16 years | Objective response rate |

| NCT02867592 | Cabozantinib | Relapsed or refractory solid tumours | II | <18 years | Objective response rate |

| NCT03514407 | iNCB059872 (LSD1 Inhibitor) |

Relapsed or refractory Ewing Sarcoma | Ib | 12 years and older | Safety and preliminary antitumor activity |

| NCT02419417 | BMS-986158 (BET Inhibitor) ± Nivolumab |

Advanced solid tumours | I/IIa | 12 years and older | Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics |

| NCT03220347 | INCB059872 | Relapsed or refractory Ewing sarcoma | I | 12 years and older | Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics |

Osteosarcoma

OGS is the most common primary bone tumor in the pediatric population.73 Two-third of patients present with localized disease and have good long-term survival. About 20% of cases have metastatic disease at diagnosis and have a poor outcome. However, about one-third of patients with localized OGS and about 80% of metastatic OGS patients relapse even after multimodality treatment. Most relapses (>50%) occur within 2 years of diagnosis and only a few relapses (<5%) after 5 years of initial diagnosis.74 The most common site of relapse is lung followed by bones and local sites. Pulmonary relapse occurs in 60–90% of cases, bone relapse in 10–20%, local relapse in 10–20% and other sites in <10%.75,76 Approach to treatment of relapsed OGS is based on sites of relapse (lungs, bones, local site or multiple), resectability and timing of relapse after the first diagnosis (Table 4).

Long-term survival in relapsed cases may be achieved in up to one-third of cases. Various factors that predict outcome in relapsed osteosarcoma include timing of relapse after initial diagnosis, sites of relapse, presence of initial metastasis, response to neo-adjuvant therapy, achievement of second complete remission (CR2) after relapse and age. Most important among these are timing of relapse and site of relapse.74

Prognosis of locally recurrent OGS without systemic metastasis is poor with long-term survival reported in 10–40% patients in retrospective studies.4,76-82 No benefit was observed with chemotherapy administration after surgical salvage.83 So locally recurrent OGS should be managed by surgical resection whenever possible. The role of chemotherapy and radiotherapy is doubtful after complete surgical resection. Additional chemotherapy may be administered after surgery as followed in unresectable disease.

Osteosarcoma: Lung Metastasis

In the majority of patients with relapsed OGS, lungs are the only site of disease. Surgery (metastasectomy) is the mainstay of management in these cases, with many cases requiring repeated or staged lung resection.83–87 Five-year event-free survival (EFS) for patients after complete surgical resection of pulmonary metastasis ranges from 20% to 45%.84,85 Overall survival with unresectable metastatic disease is less than 5%.86

In the case of isolated lung metastases, the treatment of recurrent OS is primarily surgical. Even patients with subsequent relapses may be cured as long as recurrences are resectable, and repeated thoracotomies may be required.87 Surgical resection of all macroscopic disease should be attempted with thoracoscopy or thoracotomy with palpation of the collapsed lung. There is no comparative trial or clear recommendations for using different approaches viz. thoracoscopy, unilateral or bilateral thoracotomy. Unilateral multiple metastases are usually treated with the addition of chemotherapy but the benefit is less clear. Bilateral thoracotomy with chemotherapy is required for the management of bilateral metastases. Unresectable metastases are treated with chemotherapy with palliative intent. Whether the use of preoperative chemotherapy improves the respectability of bilateral metastases is yet to be defined.88,89 The role of chemotherapy after surgery is controversial.82,90 Limited success has been achieved using radiofrequency ablation and stereotactic radiotherapy as an alternative local treatment option for primary lung or bone metastases.91,92

Osteosarcoma: Bone Metastasis

Patients with bone metastases have a poor prognosis with a 5-year EFS of 11%. However, patients who have late solitary bone relapse have a 5-year EFS of 30%.93,94 Samarium-153 ethylenediamine tetramethylene phosphonate (Sm 153-EDTMP) is a beta-particle–emitting radiopharmaceutical agent, has been studied in patients with locally recurrent or metastatic OGS. Patients with recurrent OGS with bone-only involvement can be managed by surgical resection if feasible. Patients with multiple unresectable bone lesions, 153Sm-EDTMP with or without stem cell support provide good pain relief.95,96

Radium-223 dichloride (Ra 223) is alpha-particle–emitting radiopharmaceutical that is under trials for treating metastatic or recurrent OGS. Preliminary studies suggest that this agent is active in OGS and may have less marrow toxicity and greater efficacy than beta-particle–emitting radiopharmaceuticals such as Sm 153-EDTMP.97,98

Osteosarcoma: Palliative Chemotherapy

Patients with unresectable disease are treated with conventional chemotherapy with palliative intent. The role of chemotherapy for recurrent OS is much less well defined. The choice of chemotherapy depends on the prior disease-free interval and includes ifosfamide or cyclophosphamide, with etoposide and/or carboplatin, gemcitabine and docetaxel, sorafenib or regorafenib and radioactive agents. Various agents and their responses are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies Using Chemotherapeutic Agents in Relapsed Osteosarcoma

| Author | Year of Publication | Phase | Number | Regimen | ORR % | CR/PR (Number) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harris et al99 | 1995 | II | 30 | Ifosfamide | 30 | 1/2 |

| Kung et al183 | 1993 | II | 32 | Ifosfamide + Etoposide | 15 | 2/3 |

| Miser et al184 | 1987 | II | 8 | Ifosfamide + Etoposide | 37 | 0/3 |

| Cairo et al185 | 2001 | II | 23 | Ifosfamide + Etoposide + Carboplatin | 30 | NA |

| Berrak et al186 | 2005 | R | 16 | High dose Ifosfamide | 62 | 6/4 |

| Gentet et al100 | 1997 | II | 27 | High dose Ifosfamide + Etoposide | 48 | 6/7 |

| Lee et al101 | 2016 | R | 28 | Gemcitabine + Docetaxel | 14 | 1/1 |

| Navid et al187 | 2008 | R | 17 | Gemcitabine + Docetaxel | 17 | 0/3 |

| Qi et al188 | 2012 | R | 18 | Gemcitabine + Docetaxel | 5 | 0/1 |

| Palmerini et al189 | 2016 | R | 40 | Gemcitabine + Docetaxel | 17 | 0/6 |

| Fox et al102 | 2012 | II | 14 | Gemcitabine + Docetaxel | 5 | 0/1 |

| Berger et al103 | 2009 | II | 26 | Cyclophosphamide + Etoposide | 19 | 0/5 |

| Rodriguez-Galindo et al104 | 2002 | II | 14 | Cyclophosphamide + Etoposide | 28 | 1/3 |

| Grignani et al105 | 2012 | II | 35 | Sorafenib | 8 | 0/3 |

| Grignani et al106 | 2015 | II | 38 | Sorafenib + Everolimus | 5 | 0/2 |

| Duffaud et al107 | 2019 | II | 43 | Regorafenib | 8 | 0/2 |

| Davis et al108 | 2019 | II | 42 | Regorafenib | 13 | 0/3 |

Abbreviations: CR, complete remission; ORR, overall response rate; PR, partial remission; R, retrospective.

Ifosfamide with etoposide/carboplatin has shown some response in retrospective and Phase 2 trials. Responses have been observed in about one-third of cases. Higher responses were observed in high dose ifosfamide.99,100 The combination of gemcitabine and docetaxel has an overall response rate of less than 20%. A 900 mg/m2 dose of gemcitabine was associated with a higher response rate and longer survival than 675 mg/m2 dose.101,102 Cyclophosphamide and etoposide have shown some activity in recurrent OGS in two phase 2 trials.103,104

Targeted inhibition of molecular pathways viz. mTOR, SRC kinases, and vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs) are currently under clinical trials in relapsed or refractory OGS. The Italian Sarcoma Group reported a poor response rate with sorafenib alone or in combination with everolimus. However, disease stabilization was observed in half of the cases at 6 months.105,106 Two phase 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled have evaluated the efficacy of regorafenib in OGS whose disease had progressed after treatment with at least one previous line of chemotherapy for metastatic disease. Responses were observed in 8–13% cases; however, at least stable disease was seen in up to 64% cases at 8 weeks.107,108

In the Italian Sarcoma Group study, carboplatin and etoposide followed by peripheral blood autologous stem cell transplantation, the 3-year OS and DFS rates were 20% and 12%, which is similar to that achieved with the conventional chemotherapeutic approach.109,110 So currently HDT followed by AHSCT is not recommended. Current approaches for treating OGS using novel therapeutics are given in Table 5.

Osteosarcoma: Newer Advances

Immunotherapy targeting the PD1-PDL1 axis has shown only modest activity in relapsed and refractory OGS patients. In the SARC28 study of pembrolizumab, in advanced bone and soft tissue sarcoma patients, only one partial response was observed among 22 patients with OGS, and median progression-free survival was 8 weeks.111 Prospective data from trials involving other immune checkpoint inhibitors are pending. Novel immunotherapeutic agent for the lung metastases includes inhalation of aerosolized granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). GM-CSF stimulates the proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells and augments the function of neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. However, no significant benefit was observed in 43 patients with pulmonary relapse from OGS in the American Osteosarcoma Study Group (AOST) protocol 0221.112

Osteosarcoma: Ongoing Studies

AOST1421 (NCT02484443) is currently studying combination dinutuximab (anti-GD2 antibody) with sargramostim (GM-CSF) in patients after complete surgical resection of pulmonary metastasis at recurrence.

NCI-COG Paediatric Molecular Analysis for Therapeutic Choice (MATCH) in patients between 1 and 25 years of age is next-generation sequencing-based study in refractory and recurrent solid tumours.Children and adolescents aged 1 to 21 years are eligible for the trial.AOST1321 (NCT02470091) is a single-arm, phase II trial of RANKL inhibitor denosumab, in patients with relapsed or refractory OGS post resection of any measurable disease.

Ewing Sarcoma [EWS]/Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor [PNET]

EWS is the second most common primary bone tumour after OGS.113 With currently available therapeutic modalities good outcomes have been achieved; however, relapses occur in about 30–40% of localized disease and up to 80% with advanced disease.114 Most of the relapses, about 70–80% occur early (within 2 years of diagnosis). Late (2–5 years) and very late (after 5 years of diagnosis) relapses occur in about 20–30% and 5 −10% patients, respectively.115,116 At relapse, most patients have metastatic disease or combined distant and local disease (75−85%). About 15–25% of relapses occur only at the local site, and these are more common with initially localized disease. Lungs are the most common sites of distant relapse followed by bones.6,114 At the time of relapse, about 52% of patients have symptoms, while remaining patients are diagnosed during follow-up imaging.117

The most important prognostic factors are interval between initial diagnosis and subsequent relapse, and site of relapse. Other prognostic factors for poor survival at relapse include high LDH at relapse, age >15 years, non-pulmonary metastasis and symptomatic relapse.114,117,118

No standard approach is available for the treatment of recurrent EWS. Multimodality treatment including surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy is required and depends on previous therapy, duration from diagnosis to relapse, and site of relapse. Relapsed cases are considered a systemic disease and chemotherapy is recommended in all cases. Survival with only local recurrence is better compared with distant and combined recurrences.118 If operable, the patient should undergo surgery and systemic chemotherapy. Radiotherapy may be used in case of inoperable cases, and if margin positivity after surgery. In cases of metastatic disease, chemotherapy is administered with palliative intent. Accepted approach is summarized in Table 4.

EWS/PNET: Systemic Therapy

There is no standard second-line regimen following relapse after the first‐line treatment. Several regimens have been tried, mostly retrospective evidence is available with only a few Phase 1/2 trials. No single regimen had been proven to be superior to others. Various regimens (Table 3) with promising results includes temozolomide + irinotecan ± vincristine, cyclophosphamide + topotecan, gemcitabine + docetaxel, high dose ifosfamide, ifosfamide + etoposide ± carboplatin (ICE).62,83,102,119-123 Responses with targeted therapy and immunotherapy have been poor.

Table 3.

Chemotherapy Regimens in Relapsed Ewing’s Sarcoma

| Author | Year of Publication | Study Nature | Number | Chemotherapy | ORR (%) | CR/PR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temozolomide + Irinotecan | ||||||

| Wagner et al119 | 2007 | Retrospective | 14 | Temozolomide + Irinotecan | 29 | 1/3 |

| Anderson et al190 | 2008 | Retrospective | 25 | Temozolomide + Irinotecan | 64 | 7/9 |

| Casey et al191 | 2009 | Retrospective | 19 | Temozolomide + Irinotecan | 63 | 5/7 |

| Hernández et al192 | 2013 | Retrospective | 8 | Temozolomide + Irinotecan | 37 | 0/3 |

| Raciborska et al193 | 2013 | Retrospective | 22 | Temozolomide + Irinotecan + VCR | 54 | 5/7 |

| Kurucu et al194 | 2015 | Retrospective | 20 | Temozolomide + Irinotecan | 55 | NA |

| Palmerini et al124 | 2018 | Retrospective | 51 | Temozolomide + Irinotecan | 34 | 5/12 |

| Buyukkapu et al195 | 2018 | Retrospective | 15 | Temozolomide + Irinotecan + VCR | 40 | 4/2 |

| Topotecan + Cyclophosphamide | ||||||

| Saylors et al120 | 2001 | II | 17 | Topotecan + Cyclophosphamide | 35 | 2/4 |

| Hunold et al196 | 2006 | Retrospective | 54 | Topotecan + Cyclophosphamide | 32 | 0/16 |

| Farhat et al197 | 2013 | Retrospective | 14 | Topotecan + Cyclophosphamide | 21 | 0/3 |

| Kebudi et al121 | 2013 | Retrospective | 14 | Topotecan + Cyclophosphamide | 50 | 2/5 |

| Gemcitabine + Docetaxel | ||||||

| Fox et al102 | 2012 | II | 14 | Gemcitabine + Docetaxel | 6 | 0/2 |

| Mora et al198 | 2009 | Retrospective | 6 | Gemcitabine + Docetaxel | 67 | 3/1 |

| Tanaka et al122 | 2016 | Retrospective | 4 | Gemcitabine + Docetaxel | 25 | 0/1 |

| Others | ||||||

| Ferrari et al123 | 2009 | Retrospective | 37 | High dose Ifosfamide | 34 | 02/10 |

| van Maldegem et al199 | 2015 | Retrospective | 107 | Etoposide + platinum | 27 | 15/14 |

| Van Winkle et al62 | 2005 | I/II | 22 | Ifosfamide + carboplatin +Etoposide | 48 | 7/14 |

| Devadas et al125 | 2019 | Retrospective | 49 | Tamoxifen + Etoposide + Cyclophosphamide | 59 | 21/8 |

Abbreviations: CR, complete remission; ORR, overall response rate; PR, partial remission; VCR, vincristine.

Among the various regimens, temozolomide combined with irinotecan has the most encouraging results. Additional vincristine has also been used with this regimen. Among overall 176 combined patients from various studies, responses had been observed in around 40% of patients.119,124 This regimen is well tolerated with lower myelotoxicity and fewer grade 3/4 toxicities (diarrhoea 5–10%, neuropathy 4–12%) compared with other salvage regimens. Irinotecan has been tried by the oral route, and initial studies have shown similar efficacy as the parenteral route. As oral temozolomide is available, this regimen may be considered for oral therapy.119

Topotecan and cyclophosphamide combination has shown some efficacy with 32% response rate in 99 patients from various studies. Grade 3/4 hematological toxicity was observed in more than 50% of patients.120,121 Gemcitabine with docetaxel has 29% response rate in 29 treated patients. Grade 3/4 neutropenia was seen in around 70% of patients.102,122 Ifosfamide, etoposide, and carboplatin (ICE) combination and high dose Ifosfamide had shown good efficacy but the cost of toxicity (100% Grade 3/4 haematological toxicity).62,123 A retrospective study from India has shown encouraging results with oral metronomic therapy using tamoxifen, etoposide, and cyclophosphamide. In 49 relapsed sarcoma patients, the majority of which was EWS, responses were observed in 59% of patients.125 Ongoing clinical trials using novel therapeutics for the management of refractory Ewing’s sarcoma are given in Table no. 5.

The Euro Ewing Consortium is currently conducting a multi-armed phase II/III randomized study (rEECur study) in patients aged 2–50 years with recurrent EWS. (ISRCTN 36453794). In Phase II patients will receive one of four regimens, cyclophosphamide/topotecan, gemcitabine/docetaxel, high dose ifosfamide, or temozolomide/irinotecan. In Phase III two regimens with a higher objective response rate will be tested with progression-free survival as the primary endpoint.

EWS/PNET: Targeted Therapy

Various pathways have been identified in EWS, as targets which may help in disease control. These include insulin growth factor receptor 1 (IGF-1R), vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR), MET, EWS-FLI1 fusion, DNA repair protein PARP1, lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD-1), and placenta growth factor (PGF).126–133

IGF-1R is expressed on EWS tumour cells and drives the growth of tumour cells. Initial trials with monoclonal antibodies against IGF −1R showed some encouraging results but larger studies failed to provide significant results. Studies have been done in combination with an mTOR inhibitor, but also failed to provide meaningful benefit. Current trials of IGF-1R in combination with conventional chemotherapy are ongoing [NCT02306161].134–137

Targeting angiogenesis has been attempted with modest success using regorafenib, and cabozantinib. In heavily pre-treated adult patients treated with regorafenib, response was observed in 10% and 73% of patients were progression-free at 8 weeks.137 With MET inhibitor cabozantinib responses have been observed in around 28% and 24% of patients were progression-free at 6 months.129

EWS-FLI1 is the principal driver of tumour growth in EWS. EWS-FLI1 fusion protein is a possible target for therapy in relapsed cases; however, it is very difficult to target.131 BRD4 protein is a member of the bromodomain and extra terminal domain (BET) family of proteins, is a transcriptional regulator required for the EWS-FLI1 fusion protein function. Bromodomain inhibitors inhibit gene expression of EWS-FLI1.132 Clinical trials using bromodomain inhibitors are currently ongoing [NCT02419417, NCT03220347].

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) is a family of proteins involved in various cellular processes including DNA repair and genomic stability. The expression of PARP1 is elevated in EWS. Olaparib did not have an objective clinical response in a phase 2 trial, though patients were not selected based on biomarkers.138 Currently, trials are undergoing which are selecting patients based on actionable mutation olaparib (NCT03233204), talazoparib (NCT02116777) and niraparib (NCT02044120).

Lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD-1) regulates histone methylation and influences the epigenetic state of cells, is upregulated in EWS. It is a transcriptional repressor of downstream targets of EWS/FLI1 and inhibits tumour growth.139 Clinical trials are currently ongoing with LSD −1 inhibitors [NCT03514407, NCT03600649]. Other targets that have been identified are NKX2.2, HSP90, FOX01 and ATR.140

EWS/PNET: Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy targeting PD-1/PD-L1 axis has shown disappointing results in relapsed EWS. PDL1 expression has observed in around 20% of cases; however, these have low mutational tumour burden (TMB), and low level of tumour infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL).43,141 No objective responses have been observed in patients treated with the anti-PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab or nivolumab.111,142

A novel strategy in the field of immunotherapy for EWS known as Vigil or FANG has shown promising results. In this tumor cells are obtained by biopsy or resection and transfected with a plasmid containing the rhGMCSF (recombinant human GM-CSF) transgene and the shRNAfurin(short hairpin RNA inactivating furin). This leads to the upregulation of the immune system by inhibition of TGF-beta1 and 2 mediated pathways.139,143 Ghisoli et al144 have reported a 1-year survival of 73% for relapsed EWS patients treated with Vigil compared to 23% for those treated with conventional chemotherapy. A phase III trial is currently undergoing in which relapsed EWS patients are treated with temozolomide/irinotecan combination with and without Vigil [NCT03495921].

EWS/PNET: Role of ASCT

The role of HDT followed by ASCT is doubtful in relapsed EWS due to the lack of any prospective trial in this population. Various retrospective analyses have shown the benefit of HDT followed by ASCT. However, ASCT was done in the patients responding to initial chemotherapy. This limits the role of ASCT in relapsed EWS and it is not routinely recommended.145–147 Temozolomide/Irinotecan-based chemotherapy may be favored due to higher responses and lower toxicity.

Infantile Fibrosarcoma

Infantile fibrosarcoma (IF) also known as congenital fibrosarcoma is a rare soft tissue tumor that presents at birth or develops in the 1st year of life. They represent approximately 5% to 10% of all sarcomas in infants.148–150 It has a reciprocal translocation, t(12;15)(p13;q25), resulting in ETV6/NTRK3 gene fusion in which the ETV6 (TEL) gene from 12p13 fuses with the NTRK3 gene (Trk C) on 15q25.151

The European Paediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group evaluated a conservative therapeutic strategy in 50 infants with localized IFS. The initial surgery was performed if it could be done without mutilation. No further therapy was given if negative margins (group I/R0; n=11) or microscopic positive margins (group II/R1; n=8). Non-alkylator-based chemotherapy vincristine-actinomycin (VA) was administered to those with initial inoperable tumours (group III/R2; n=31). Response to chemotherapy was observed in 68% of patients. The 3-year event-free survival was 84% and the overall survival 94.0% at a median follow-up of 4.7 years.152

As discussed, ETV6/NTRK3 gene fusion is found in patients with IF. Larotrectinib is an oral ATP-competitive inhibitor of TRK A, B, and C. In a phase I/II basket trial involving 55 adults and paediatric patients with advanced or metastatic tumours with TRK fusion proteins, seven patients with IF were included. All patients responded to larotrectinib with two patients achieved complete remission and five achieved partial responses.153 Larotrectinib was approved by the FDA for use in adults and children with solid tumours with an NTRK gene fusion without a known acquired resistance mutation, which are either metastatic or where surgical resection is likely to result in severe morbidity, and who have no satisfactory alternative treatments or who have progressed following treatment.

In a patient with IF, upfront surgical resection should be considered. If the tumour is very large and a mutilating surgery is expected, neoadjuvant therapy similar to RMS may be administered. In cases of relapsed and metastatic IF, where the tumour is not surgically amenable, the patient should be started on larotrectinib or enrolled in a clinical trial. Summary of current modalities is mentioned in Table 4, recent novel therapeutic approaches are given in Table 5.

Non-Chemotherapeutic Approaches in Refractory Pediatric Sarcoma Including Newer Advances

Metronomic Therapy

Metronomic therapy is low-dose, prolonged, continuous administration of drugs that inhibits angiogenesis.154,155 Metronomic therapy was shown to be safe and well tolerated in a study of 16 children with relapsed/refractory patients which included five patients with OGS.156 A randomized controlled trial comparing metronomic therapy with placebo, in extracranial non-hematopoietic paediatric solid tumours, post lines of chemotherapy were done to evaluate the role of metronomic therapy with the proportion of patients without disease progression as an endpoint. There was no significant difference between the two groups. However, in post hoc subgroup analysis patients who received more than three cycles and did not have bone sarcoma benefited with metronomic therapy.157 Metronomic therapy needs to be explored in a palliative setting, in clinical trials designed for this group of patients.

Immune Check-Point Inhibitors

Few STS[1–5%] may have genomic instability in the form of Microsatellite instability [MSI], such as MSI-H, which is the biologic basis of deficient mismatch repair (dMMR).158 They may respond to anti-programmed death receptor 1 [PDl] or anti-programmed death receptor ligand 1 [PDL1] inhibitors. Recently FDA has approved pembrolizumab, a PD1 inhibitor as a treatment option in certain advanced solid tumours including STS that are refractory to standard of care therapy which are MSI-H or dMMR.159 PD-1–expressing TILs and tumour PD-L1 expression were seen in 65% and 58% of tumours in 105 cases of various STS sub-types. Initial immunotherapy trials did show a modest response in advanced STS with few tumour types showed predominantly stable disease.160–163 Second study showed encouraging results in some adult-type STS [dedifferentiated liposarcoma & undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma] but none in paediatric sarcoma.111

Ipilimumab a CTLA4 immune checkpoint inhibitor was evaluated in Phase I clinical trial for refractory pediatric sarcoma which included OGS and RMS. No objective responses were seen.161 Similarly, a phase I/II trial in relapsed refractory Ewing’s sarcoma and OGS using nivolumab and combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab did not show any objective response.163

Immunotherapy probably will not be as effective as in adult oncology because pediatric cancers have less tumor mutational burden, immune system in children is still maturing and regulatory T cells present in the microenvironment of pediatric sarcomas have high immunosuppressive action which hinders immunotherapy.72 Many clinical trials ongoing on refractory STS evaluating the role of immunotherapy and the majority of them include adult patients with STS (Table 5).

Cancer Vaccines

Dendritic cell vaccine is a novel approach that appears to be promising. In metastatic and refractory pediatric sarcoma autologous lymphocyte infusion plus sequential autologous tumor lysate vaccines were administered as adjuvant therapy after completion of conventional therapy. Five-year survival was 63% in patients with EWS and RMS and 74% in patients who did not have any residual disease after conventional therapy.164

CAR-T Therapy

In view of the limitations of immune checkpoint inhibitors in refractory pediatric sarcoma, CAR-T cells have generated a lot of interest. The key challenges lie in the rarity of the disease and finding an appropriate target. To circumvent these problems current research is focussing on developing CAR-T cells against antigens which are present in other tumors as well as refractory pediatric tumors.165 Phase I clinical trials of EGFR as CAR-T cells as target in OS, RMS and EWS (NCT03618381) are going on. GD2 is another target of CAR-T cells that are currently being tried in OGS, EWS and sarcoma (NCT01953900, NCT02107963, NCT03356782). Infantile fibrosarcoma with a high level of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes with high expression of costimulatory molecules suggests that adoptive T-cell therapy could be an option.166

Promising Immunotherapeutic Approaches in Pediatric Sarcomas

Paediatric sarcomas express fewer neoantigen than adult type and distinguish them distinctly from adult STS in terms of pathogenesis as well as response to immune checkpoint inhibitors.167 Neoantigen expression is vital for immune cell infiltration in the tumor microenvironment and subsequent immune-mediated cell killing. The discovery of neoantigen and development of directed therapy is of paramount importance. Surface targets such as ganglioside GD2 and GD3 are expressed in paediatric sarcomas and also IGF1R in Ewing’s sarcoma. These surface antigens can be targeted with advanced targeted therapy including CAR-T cell therapy.168

However, it is pertinent to note that novel therapeutical approaches that have been successful in other cancers have not yet impacted the management of pediatric sarcoma patients. INFORM study and other studies using the “omics” approach have generated huge genetic, epigenetic, gene expression data along with the identification of new driver mutations, but patients have not benefited in terms of survival from this genetic data acquisition. Immunotherapy with conventional targets has failed in pediatric refractory sarcomas. Drug screens have identified new drugs and are currently under trials, but proof of efficacy is lacking.

Future Direction

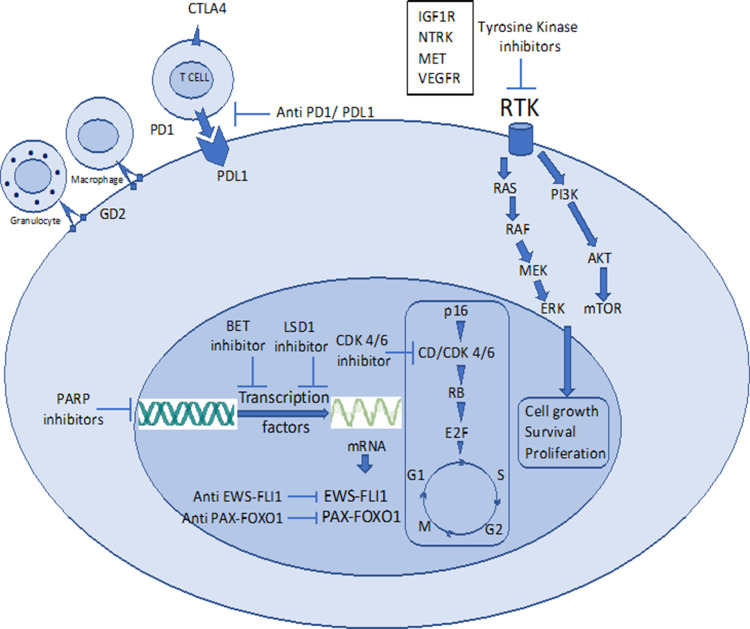

Systemic combination chemotherapy has reached a plateau in terms of cure rate & survival after huge success over the last 3 decades and has complemented by advanced surgical techniques, improved quality of life with limb salvage therapy and better prosthesis with newer engineering and improved radiation technique sparing short-&long-term treatment-related toxicities. Now, the focus is on further improving the survival, lowering long-term treatment-related toxicities, better salvage therapy in case of recurrent disease and to find the cure with research & development of newer therapeutics for metastatic disease. Newer targets in refractory sarcomas are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Newer targets in refractory pediatric sarcomas.

Abbreviations: BET, bromodomain extra terminal motif; CD Cyclin D, CDK 4/6 cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; GD2, disialoganglioside 2; IGF1R, insulin-like growth factor receptor 1; LSD1, lysine-specific histone demethylase 1; MET, mesenchymal–epithelial transition; NTRK, neurotropic tropomyosin receptor kinase; PARP, poly ADP ribose polymerase; PD1, programmed death receptor 1; PDL1, programmed death receptor Ligand 1; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Various immunotherapeutic approaches – both as single agents and in combination are in clinical studies or published with the mixed outcome and some are promising.169 Chemo-immunotherapy combination therapies can be one of the potential strategies in those with a high burden or upfront metastatic disease after the huge success of the same approach in non-small cell lung cancer.170 Cellular vaccine171 & adaptive cell therapy,172 defining kinome and development of small molecule targeted therapies [NCT02601950] are emerging & theoretically promising treatment strategies in paediatric sarcoma especially translocation associated sarcomas.

Maintenance immunotherapeutic strategy after completion of definitive initial treatment may improve the long-term outcome just like PACIFIC173 study demonstrated huge success of Durvalumab [an anti-PDL1 antibody] in stage 3 NSCLC after definitive chemoradiation and should be investigated in paediatric sarcomas. A strategy that decreases the chance of recurrence in paediatric sarcomas should be a better strategy rather than treating them on recurrence.

In the case of treatment refractoriness, a newer immunotherapeutic strategy like CAR-T cells can be an emerging & promising therapy that can cure even treatment-resistant cases, just like in haematological malignancies. International and national collaboration of multi-pronged treatment strategy, personalized & precision medicine and a better understanding of tumour genome, identification of treatment resistance mechanism, exploitation of host immunity remains the future treatment strategy in the management of relapsed & refractory paediatric sarcomas.

Conclusions

Paediatric sarcomas are heterogeneous group of disorders and nearly one-third of them presents with metastasis at presentation and another one-third relapsed after initial curative therapies. Not much of therapeutic developments happened in relapsed/refractory paediatric sarcomas and current treatment options are very much limited in terms of cure or long-term control. Multimodality treatment with chemotherapy, surgery and/or radiotherapy can be curative options in some limited relapsed cases or when relapse occurs after a long remission. But, in the majority of remaining cases, treatment refractoriness remains the main challenge and possesses a huge unmet need. Current newer strategies including targeted therapies, salvage chemotherapy, ASCT, immunotherapeutic approach, adoptive cellular therapies only produced modest & temporary responses, so far. Better understanding of disease biology, mechanism of treatment refractoriness, well-designed clinical trials, combination chemo-immunotherapeutic strategy, better national and international collaboration, translational research remains the key to success and fulfils the unmet need.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Biswas B, Rastogi S, Khan SA, et al. Hypoalbuminaemia is an independent predictor of poor outcome in metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumours: a single institutional experience of 150 cases treated with uniform chemotherapy protocol. Clin Oncol. 2014;26(11):722–729. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iqbal N, Shukla NK, Deo SVS, et al. Prognostic factors affecting survival in metastatic soft tissue sarcoma: an analysis of 110 patients. Clin Transl Oncol. 2016;18(3):310–316. doi: 10.1007/s12094-015-1369-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson ME. Update on survival in osteosarcoma. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47(1):283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2015.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelderblom H, Jinks RC, Sydes M, et al. Survival after recurrent osteosarcoma: data from 3 European Osteosarcoma Intergroup (EOI) randomized controlled trials. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(6):895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaspar N, Hawkins DS, Dirksen U, et al. Ewing sarcoma: current management and future approaches through collaboration. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(27):3036–3046. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.5256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stahl M, Ranft A, Paulussen M, et al. Risk of recurrence and survival after relapse in patients with Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(4):549–553. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grünewald TGP, Cidre-Aranaz F, Surdez D, et al. Ewing sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2018;4:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pappo AS, Anderson JR, Crist WM, et al. Survival after relapse in children and adolescents with rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(11):3487–3493. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dantonello TM, Int-Veen C, Winkler P, et al. Initial patient characteristics can predict pattern and risk of relapse in localized rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(3):406–413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chisholm JC, Marandet J, Rey A, et al. Prognostic factors after relapse in nonmetastatic rhabdomyosarcoma: a nomogram to better define patients who can be salvaged with further therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1319–1325. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sung L, Anderson JR, Donaldson SS, et al. Late events occurring five years or more after successful therapy for childhood rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group. Eur J CanceR. 1990. 2004;40(12):1878–1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazzoleni S, Bisogno G, Garaventa A, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors after recurrence in children and adolescents with nonmetastatic rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer. 2005;104(1):183–190. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dasgupta R, Rodeberg D. Non-rhabdomyosarcoma. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2016;25(5):284–289. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2016.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parida L, Fernandez-Pineda I, Uffman JK, et al. Clinical management of infantile fibrosarcoma: a retrospective single-institution review. Pediatr Surg Int. 2013;29(7):703–708. doi: 10.1007/s00383-013-3326-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loh ML, Ahn P, Perez-Atayde AR, Gebhardt MC, Shamberger RC, Grier HE. Treatment of infantile fibrosarcoma with chemotherapy and surgery: results from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Children’s Hospital, Boston. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24(9):722–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbs CP, Kukekov VG, Reith JD, et al. Stem-like cells in bone sarcomas: implications for tumorigenesis. Neoplasia. 2005;7(11):967–976. doi: 10.1593/neo.05394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tirino V, Desiderio V, d’Aquino R, et al. Detection and characterization of CD133+ cancer stem cells in human solid tumours. PLoS One. 2008;3(10):e3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adhikari AS, Agarwal N, Wood BM, et al. CD117 and Stro-1 identify osteosarcoma tumor-initiating cells associated with metastasis and drug resistance. Cancer Res. 2010;70(11):4602–4612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martins-Neves SR, Paiva-Oliveira DI, Wijers-Koster PM, et al. Chemotherapy induces stemness in osteosarcoma cells through activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Cancer Lett. 2016;370(2):286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang Q-L, Liang Y, Xie X-B, et al. Enrichment of osteosarcoma stem cells by chemotherapy. Chin J Cancer. 2011;30(6):426–432. doi: 10.5732/cjc.011.10127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown HK, Tellez-Gabriel M, Heymann D. Cancer stem cells in osteosarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2017;386:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwaya K, Ogawa H, Kuroda M, Izumi M, Ishida T, Mukai K. Cytoplasmic and/or nuclear staining of beta-catenin is associated with lung metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20(6):525–529. doi: 10.1023/A:1025821229013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang F, Chen A, Chen J, Yu T, Guo F. siRNA-mediated silencing of beta-catenin suppresses invasion and chemosensitivity to doxorubicin in MG-63 osteosarcoma cells. Asian Pac J Cancer. 2011;12(1):239–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu J, Liao Q, He H, Zhong D, Yin K. TWIST interacts with β-catenin signaling on osteosarcoma cell survival against cisplatin. Mol Carcinog. 2014;53(6):440–446. doi: 10.1002/mc.21991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma Y, Ren Y, Han EQ, et al. Inhibition of the Wnt-β-catenin and Notch signaling pathways sensitizes osteosarcoma cells to chemotherapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;431(2):274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basu-Roy U, Basilico C, Mansukhani A. Perspectives on cancer stem cells in osteosarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2013;338(1):158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.05.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajkumar T, Yamuna M. Multiple pathways are involved in drug resistance to doxorubicin in an osteosarcoma cell line. Anticancer Drugs. 2008;19(3):257–265. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3282f435b6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baldini N, Scotlandi K, Barbanti-Bròdano G, et al. Expression of P-glycoprotein in high-grade osteosarcomas in relation to clinical outcome. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(21):1380–1385. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511233332103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Windsor RE, Strauss SJ, Kallis C, Wood NE, Whelan JS. Germline genetic polymorphisms may influence chemotherapy response and disease outcome in osteosarcoma: a pilot study. Cancer. 2012;118(7):1856–1867. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ifergan I, Meller I, Issakov J, Assaraf YG. Reduced folate carrier protein expression in osteosarcoma: implications for the prediction of tumor chemosensitivity. Cancer. 2003;98(9):1958–1966. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patiño-García A, Zalacaín M, Marrodán L, San-Julián M, Sierrasesúmaga L. Methotrexate in pediatric osteosarcoma: response and toxicity in relation to genetic polymorphisms and dihydrofolate reductase and reduced folate carrier 1 expression. J Pediatr. 2009;154(5):688–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uozaki H, Horiuchi H, Ishida T, Iijima T, Imamura T, Machinami R. Overexpression of resistance-related proteins (metallothioneins, glutathione-S-transferase π, heat shock protein 27, and lung resistance-related protein) in osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1997;79(12):2336–2344. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei L, Song X-R, Wang X-W, Li M, Zuo W-S. Expression of MDR1 and GST-pi in osteosarcoma and soft tissue sarcoma and their correlation with chemotherapy resistance. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2006;28(6):445–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biason P, Hattinger CM, Innocenti F, et al. Nucleotide excision repair gene variants and association with survival in osteosarcoma patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics J. 2012;Dec;12(6):476–483. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2011.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caronia D, Patiño-García A, Milne RL, et al. Common variations in ERCC2 are associated with response to cisplatin chemotherapy and clinical outcome in osteosarcoma patients. Pharmacogenomics J. 2009;9(5):347–353. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J, Liu S, Wang W, et al. ERCC polymorphisms and prognosis of patients with osteosarcoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(10):10129–10136. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2322-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang J, Yang D, Cogdell D, et al. APEX1 gene amplification and its protein overexpression in osteosarcoma: correlation with recurrence, metastasis, and survival. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2010;9(2):161–169. doi: 10.1177/153303461000900205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen R, Wang G, Zheng Y, Hua Y, Cai Z. Drug resistance‐related microRNAs in osteosarcoma: translating basic evidence into therapeutic strategies. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(4):2280–2292. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin PP, Wang Y, Lozano G. Mesenchymal stem cells and the origin of Ewing’s sarcoma. Sarcoma. 2011;2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmed AA, Zia H, Wagner L. Therapy resistance mechanisms in Ewing’s sarcoma family tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73(4):657–663. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2392-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scotlandi K, Remondini D, Castellani G, et al. Overcoming resistance to conventional drugs in Ewing sarcoma and identification of molecular predictors of outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(13):2209–2216. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.2542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mendoza-Naranjo A, El-Naggar A, Wai DH, et al. ERBB4 confers metastatic capacity in Ewing sarcoma. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5(7):1087–1102. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201202343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crompton BD, Stewart C, Taylor-Weiner A, et al. The genomic landscape of pediatric Ewing sarcoma. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(11):1326–1341. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu X, Xiao H, Wang R, Liu L, Li C, Lin J. Persistent GP130/STAT3 signaling contributes to the resistance of doxorubicin, cisplatin, and MEK inhibitor in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2016;16(7):631–638. doi: 10.2174/1568009615666150916093110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Citti A, Boldrini R, Inserra A, et al. Expression of multidrug resistance-associated proteins in paediatric soft tissue sarcomas before and after chemotherapy. Int J Oncol. 2012;41(1):117–124. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmid E, Stagno MJ, Yan J, et al. Serum and glucocorticoid inducible kinase 1-sensitive survival, proliferation and migration of rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;43(3):1301–1308. doi: 10.1159/000481842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seitz G, Bonin M, Fuchs J, et al. Inhibition of glutathione-S-transferase as a treatment strategy for multidrug resistance in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. Int J Oncol. 2010;36(2):491–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhuvaneshwar K, Harris M, Gusev Y, et al. Genome sequencing analysis of blood cells identifies germline haplotypes strongly associated with drug resistance in osteosarcoma patients. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:1. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5474-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chiappetta C, Mancini M, Lessi F, et al. Whole-exome analysis in osteosarcoma to identify a personalized therapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8:46. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Subbiah V, Wagner MJ, McGuire MF, et al. Personalized comprehensive molecular profiling of high risk osteosarcoma: implications and limitations for precision medicine. Oncotarget. 2015;6(38):38. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang W, Brohl AS, Patidar R, et al. MultiDimensional clinOmics for precision therapy of children and adolescent young adults with relapsed and refractory cancer: a report from the center for cancer research. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(15):3810–3820. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Worst BC, van Tilburg CM, Balasubramanian GP, et al. Next-generation personalised medicine for high-risk paediatric cancer patients – the INFORM pilot study. Eur J Cancer. 2016;65:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khater F, Vairy S, Langlois S, et al. Molecular profiling of hard-to-treat childhood and adolescent cancers. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192906. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Groisberg R, Hong DS, Holla V, et al. Clinical genomic profiling to identify actionable alterations for investigational therapies in patients with diverse sarcomas. Oncotarget. 2017;8:24. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weidenbusch B, Richter GHS, Kesper MS, et al. Transcriptome based individualized therapy of refractory pediatric sarcomas: feasibility, tolerability and efficacy. Oncotarget. 2018;9(29):29. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suehara Y, Alex D, Bowman A, et al. Clinical genomic sequencing of pediatric and adult osteosarcoma reveals distinct molecular subsets with potentially targetable alterations. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(21):6346–6356. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-4032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang J, Yang D, Sun Y, et al. Genetic amplification of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway genes, including VEGFA, in human osteosarcoma. Cancer. 2011;117(21):4925–4938. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hayes-Jordan A, Doherty DK, West SD, et al. Outcome after surgical resection of recurrent rhabdomyosarcoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(4):633–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.De Corti F, Bisogno G, Dall’Igna P, et al. Does surgery have a role in the treatment of local relapses of non-metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(7):1261–1265. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Angelini L, Bisogno G, Alaggio R, et al. Prognostic factors in children undergoing salvage surgery for bladder/prostate rhabdomyosarcoma. J Pediatr Urol. 2016;12(4):265.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kung FH, Desai SJ, Dickerman JD, et al. Ifosfamide/carboplatin/etoposide (ICE) for recurrent malignant solid tumors of childhood: a Pediatric Oncology Group Phase I/II study. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1995;17(3):265–269. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199508000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Winkle P, Angiolillo A, Krailo M, et al. Ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (ICE) reinduction chemotherapy in a large cohort of children and adolescents with recurrent/refractory sarcoma: the Children’s Cancer Group (CCG) experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44(4):338–347. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rl S, Kc S, J S J, et al. Cyclophosphamide plus topotecan in children with recurrent or refractory solid tumors: a pediatric oncology group Phase II Study. J Clin Oncol. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Compostella A, Affinita MC, Casanova M, et al. Topotecan/carboplatin regimen for refractory/recurrent rhabdomyosarcoma in children: report from the AIEOP Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee. Tumori. 2019;105(2):138–143. doi: 10.1177/0300891618792479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mascarenhas L, Lyden ER, Breitfeld PP, et al. Randomized phase II window trial of two schedules of irinotecan with vincristine in patients with first relapse or progression of rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(30):4658–4663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.7390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abstracts S. Pediatr blood cancer. 2019;66(S4):e27989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weigel BJ, Breitfeld PP, Hawkins D, Crist WM, Baker KS. Role of high-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell rescue in the treatment of metastatic or recurrent rhabdomyosarcoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23(5):272–276. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200106000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peinemann F, Kröger N, Bartel C, et al. High-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation for metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma–a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rengaswamy V, Zimmer D, Süss R, Rössler J. RGD liposome-protamine-siRNA (LPR) nanoparticles targeting PAX3-FOXO1 for alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma therapy. J Controlled Release. 2016;235:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.05.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gryder BE, Yohe ME, Chou H-C, et al. PAX3–FOXO1 establishes myogenic super enhancers and confers bet bromodomain vulnerability. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(8):884–899. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Böhm M, Wachtel M, Marques JG, et al. Helicase CHD4 is an epigenetic coregulator of PAX3-FOXO1 in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(11):4237–4249. doi: 10.1172/JCI85057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen C, Dorado Garcia H, Scheer M, Henssen AG. Current and future treatment strategies for rhabdomyosarcoma. Front Oncol. 2019;20;9(20):1903–1904. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(75)90415-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arndt CA, Crist WM. Common musculoskeletal tumors of childhood and adolescence. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(5):342–352. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907293410507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Link MP, Goorin AM, Miser AW, et al. The effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on relapse-free survival in patients with osteosarcoma of the extremity. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(25):1600–1606. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198606193142502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gelderblom H, Jinks RC, Sydes M, et al. Survival after recurrent osteosarcoma: data from 3 European Osteosarcoma Intergroup (EOI) randomized controlled trials. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(6):895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kempf-Bielack B, Bielack SS, Jürgens H, et al. Osteosarcoma relapse after combined modality therapy: an analysis of unselected patients in the Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study Group (COSS). J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(3):559–568. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ferrari S, Briccoli A, Mercuri M, et al. Late relapse in osteosarcoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006;28(7):418–422. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000212944.82361.1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]