Abstract

Management of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma is challenging. With an increasing number of options for the first and second-line treatment, understanding and developing optimal systemic treatment strategies are crucial. In second line, two tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) and one monoclonal antibody have been approved after sorafenib by both the European Medicines Agency and the Food and Drug Administration based on the results of phase 3 trials: cabozantinib, regorafenib and ramucirumab. Cabozantinib has demonstrated an improved overall survival and progression-free survival in the phase 3 CELESTIAL study in second and third line, in patients in good general condition (performance status 0–1) and with a normal liver function Child-Pugh class A. Analysis of subgroups has shown that even elderly patients over 65 years, or patients with high baseline alpha-fetoprotein ≥400 ng/mL benefit from cabozantinib. The choice in second-line between the three drugs should be based on factors such as previous tolerance of sorafenib, safety profile of drugs and quality of life. In this review, we will analyze clinical data available on cabozantinib, clarifying the choice between the different possible treatments. However, the upcoming of a new standard in first line with the combination atezolizumab and bevacizumab will change the game and will warrant further investigations to define the accurate subsequent sequence of TKIs. Cabozantinib is also actually tested in first-line in combination with atezolizumab, results of the phase 3 COSMIC trial are eagerly awaited.

Keywords: advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, cabozantinib, MET, alpha-fetoprotein, AFP, tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fourth most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide.1 The incidence of HCC is increasing, reaching almost one million new cases per year worldwide.1 In the past years, there has been a change in epidemiology concerning the etiology of liver disease. While there is a decrease of viral causes (hepatitis B and C), liver complications of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis are growing. HCC more often develops in cirrhotic patients (>80% of cases), but in case of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis it could occur in almost 40% of patients without cirrhosis.2 These epidemiological changes, combined with a better control of viral C infections and of the underlying liver disease, have led to an increase in the number of patients with preserved liver function developing HCC and thus eligible for systemic treatment.

Frequently, patients are initially diagnosed at an advanced stage. However, more and more patients are diagnosed at an earlier stage thanks to screening in cirrhotic patients, but will eventually progress to advanced HCC and be treated with systemic therapies. Until 2016 sorafenib was the only drug to improve median overall survival (OS) in patients with advanced HCC.3 Since then, three other oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) have shown clinical benefit in phase 3 trials:4–6 lenvatinib in first line, regorafenib and cabozantinib in second line after sorafenib failure. Additionally, ramucirumab, a monoclonal antibody that selectively targets vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR-2), has demonstrated an improvement of OS in second-line treatment in patients with alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) ≥ 400 ng/mL.7 Promising results concerning immunotherapy in first and second line setting have been published but have failed to reach clinical significance in phase 3 trials.8,9 Finally, the combination of atezolizumab (immunotherapy, anti-PD-L1) with bevacizumab (monoclonal antibody targeting VEGF) has very recently demonstrated a significant improvement of OS compared to sorafenib in first line setting and will probably be the standard of care in first line in a near future.10

In this article, we will discuss the place of cabozantinib for the treatment of advanced HCC, and emphasize clinical data that can help in decision making between cabozantinib and other validated systemic drugs.

Overview of Systemic Therapies in Advanced HCC

Definition of Advanced HCC

Advanced HCC is defined, according to the latest EASL recommendations,11 by the presence of macroscopic portal invasion and/or extrahepatic spread, in patients with preserved liver function (Child-Pugh class A) and good performance status (PS). Other situations are more debated, particularly the case of patients progressive after transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread. Integrating TACE failure, these patients are eligible for systemic treatment even if they belong to stage B of the BCLC classification. In advanced HCC, systemic therapies represent the standard of care in patients in good general condition PS 0–2, and with a normal liver function.

First Line Therapies

The first drug approved in this setting was sorafenib in 2008, following the results of the phase III randomized SHARP study,3 showing a significant increase in OS compared to placebo (10.7 vs 7.9 months, HR 0.69). This HR represents a statistically and clinically meaningful reduction in the risk of death.

Lenvatinib, a multi TKI of VEGFR 1 to 3, FGF receptors 1 to 4, PDGF α receptor, RET and KIT, showed comparable efficacy to sorafenib in a phase III non-inferiority study,4 in patients with advanced HCC.

Finally, the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) with an antiangiogenic agent, has been tested in HCC; results of the phase 3 IMbrave150 study comparing the combination therapy vs sorafenib in first line were recently reported.10 The association atezolizumab/bevacizumab significantly prolonged OS and PFS compared to sorafenib; median OS with the combination was not estimable vs 13.2 months with sorafenib (HR 0.58; 95% CI, 0.42–0.79; p = 0.0006).

Second Line Therapies

Cabozantinib: Mechanism of Action, Clinical Efficacy, Safety

Mechanism of Action

Cabozantinib is an oral TKI, targeting VEGFR 1 to 3, MET, AXL, KIT and RET. The MET tyrosine kinase receptor is a receptor for hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) which is an important signaling pathway for cell proliferation and survival.12 Angiogenesis plays a crucial role in tumor progression, regulated by interactions between VEGF and VEGFR. HGF is also an angiogenic factor and acts synergistically with VEGF to induce angiogenesis. Therefore by inhibiting both MET and VEGFR pathways, cabozantinib provides antitumor activity.

Clinical Efficacy

It was first tested in a phase 1 study,13 enrolling 85 patients with solid tumors, mainly medullary thyroid carcinoma; only one patient had HCC. Cabozantinib demonstrated an acceptable safety profile, dose-dependent exposure and half-life supporting once daily dosing, with only moderate inter-individual variability.

Based on these preliminary data, a multicentric phase 2 study was conducted in 526 patients with 9 tumor types including advanced HCC.14 Forty-one patients with advanced HCC, a normal liver function (Child-Pugh A), and at least one prior systemic anticancer agent, received cabozantinib 100mg daily during a 12-week lead-in phase. After the initial 12-week treatment period, patients with stable disease were randomized either to cabozantinib or placebo. At week 12, objective response rate (ORR) was 5%; disease control rate (DCR) was 66%. Median PFS after randomization was 2.5 months with cabozantinib and 1.4 months with placebo, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Finally the phase 3, randomized, double-blinded, controlled, CELESTIAL trial was completed.6 It included 707 patients with a pathological diagnosis of HCC not accessible to curative treatment, Child-Pugh class A liver function and a PS score of 0 or 1. Patients were eligible if they had received previous treatment with sorafenib and had a progressive disease after at least one systemic treatment, but they could have received up to two prior drugs. Patients were randomized to receive either 60mg of cabozantinib once daily or placebo in a 2:1 ratio, with stratification according to disease etiology, region (Asia vs other), and presence of extrahepatic spread and/or macrovascular invasion (yes vs no). The primary endpoint was OS in the intention to treat population; secondary endpoints were PFS and ORR. The median OS was 10.2 months in the cabozantinib group and 8 months in the placebo group, with a HR for death of 0.76 (95% CI 0.63–0.92) and a p value of 0.005. Results concerning OS were consistent across all subgroups, including patients with macrovascular invasion (HR 0.75 [95% CI 0.54–1.03]) or extrahepatic spread (HR 0.72 [95% CI 0.58–0.89]). Median PFS assessed by the investigator was 5.2 months with cabozantinib vs 1.9 months with placebo (HR 0.44 [95% CI 0.36–0.52], p <0.001). ORR according to RECIST criteria was 4% with cabozantinib and less than 1% with placebo (p = 0.009). The outcomes of 495 patients who had received sorafenib as the only prior systemic therapy in the phase 3 CELESTIAL study were presented at ASCO 2018.15 Median OS was 11.3 months with cabozantinib vs 7.2 months for placebo (HR 0.70 [95% CI 0.55–0.88]).

Safety and Tolerability

The safety profile of cabozantinib is close to other TKIs. In the CELESTIAL trial,6 adverse events (AEs) of any grade were reported in 99% of patients, and AEs of grade 3 or more were reported in 68% of patients. The most common AEs of grade 3 or 4 were palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (17%), hypertension (16%), increased level of aspartate aminotransferase 12%), fatigue (10%) and diarrhea (10%). Grade 5 AEs related to cabozantinib were rare (6 out of 467 patients). However, dose reductions were frequent and concerned 62% of patients. The median average daily dose of cabozantinib was 35.8mg.

Regorafenib

In second line setting, regorafenib, an oral multikinase inhibitor targeting VEGFR 1 to 3, RET, KIT and PDGF receptor, has shown improvement of OS compared to placebo (10.6 vs 7.8 months; HR 0.63) in the RESORCE trial,5 after failure of sorafenib in patients who tolerate it. Intolerance was defined by the administration of less than 400mg of sorafenib per day for at least 20 days in the month before stopping sorafenib for progression. Median PFS was 3.1 months with regorafenib vs 1.5 months with placebo. AEs were reported in all patients treated with regorafenib, the most common grade 3 or 4 treatment related AEs were hypertension (15%), hand-foot skin reaction (13%), fatigue (9%) and diarrhea (3%). No differences were found in terms of quality of life (QoL) between regorafenib and placebo. Regorafenib is currently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) as a second-line treatment of advanced HCC in patients who tolerated previous sorafenib.

Ramucirumab

Ramucirumab, a human monoclonal antibody that selectively targets VEGFR-2 has been developed. The REACH-2 study,7 a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III study, evaluating ramucirumab as second-line treatment following first-line sorafenib in patients with advanced HCC and elevated AFP levels at baseline (≥400 ng/mL) has shown an increase in median OS (8.5 months in the ramucirumab group and 7.3 months in the placebo group; HR 0.71) and PFS (2.8 months vs 1.6 months; HR 0.452). Treatment-related AEs of any grade were reported in 11% of patients treated with ramucirumab, mostly fatigue, decreased appetite or nausea, hypertension, proteinuria, and bleeding. Based on these results, FDA and EMA approved ramucirumab for patients with advanced HCC previously treated with sorafenib and baseline AFP over 400ng/mL.

Immunotherapies

Additionally, immunotherapies have been investigated in advanced HCC, particularly anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies. Nivolumab and pembrolizumab received accelerated approval by FDA in second line after failure of sorafenib following encouraging results in phase 1 and 2 studies with interesting ORR of respectively 20% and 17%.16,17 However, in phase 3 trials, both pembrolizumab and nivolumab failed to demonstrate an improvement in OS and PFS as single agents. In the KEYNOTE-240 trial,8 median OS was 13.9 months with pembrolizumab versus 10.6 months for placebo (HR 0.781; p=0.0238); median PFS for pembrolizumab was 3 months vs 2.8 months for placebo (HR 0.718; p =0.0022) with a pre-specified one-sided significance thresholds p=0.0174 and 0.002, respectively. In the CHECKMATE-459 study,9 nivolumab was tested in first line compared to sorafenib; OS did not meet the predefined threshold of statistical significance. Median OS was 16.4 months for nivolumab and 14.7 months for sorafenib (HR 0.85; p =0.0752). There is no European approval for the use of either nivolumab or pembrolizumab in second line setting.

The mechanism of action and efficacy of validated drugs in second line are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Validated Drugs for the Treatment of Advanced HCC in Second Line

| Cabozantinib | Regorafenib | Ramucirumab | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target | VEGFR 1–3, RET, MET, AXL, KIT | VEGFR 1–3, RET, KIT, PDGFR | VEGFR-2 |

| Control arm | Placebo | Placebo | Placebo |

| OS (months) HR, p value |

10.2 vs 8.0 0.76, p = 0.005 |

10.6 vs 7.8 0.63, p < 0.0001 |

8.5 vs 7.3 0.71, p = 0.0199 |

| PFS (months) HR, p value |

5.2 vs 1.9 0.44, p < 0.001 |

3.1 vs 1.5 0.46, p < 0.0001 |

2.8 vs 1.6 0.452, p < 0.0001 |

| ORR | 4% vs 0.4% | 11% vs 4% | 4.6% vs 1% |

Third Line Therapies

To date, the only drug tested in third line for the treatment of advanced HCC is cabozantinib. However, it was not a dedicated study, but a subgroup analysis. In the subgroup of patients (n = 192) who had received two prior systemic therapies in the CELESTIAL trial,6 130 were treated with cabozantinib, 62 with placebo. HR for death was 0.90 (95% CI 0.63–1.29); HR for PFS was 0.58 (95% CI 0.41–0.83). In this sub-analysis, cabozantinib seems effective in third line, despite a non-significant result in OS that could be affected by statistical variability due to the small population in this subgroup.

Cabozantinib for the Treatment of HCC in Second Line: Patient Selection, Special Considerations

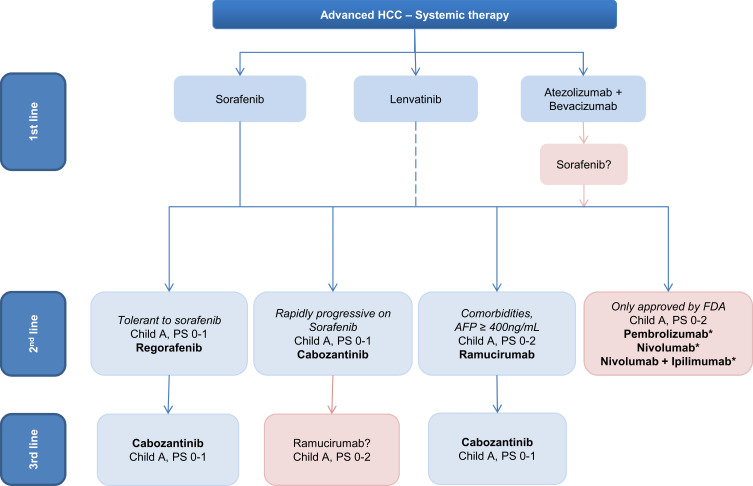

In second line, three treatment options are validated in phase III trials and currently available (cabozantinib, regorafenib and ramucirumab), but there are no clear guidelines for the moment allowing a choice between them. In decision making, several factors should be taken into account: condition of patients (PS, age, liver function), efficacy and tolerance of the drug, quality of life and other elements that will be detailed below. According to these factors, we suggest a treatment algorithm in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for management of advanced HCC.

Note: *No positive phase 3 trials.

Abbreviations: PS, performance status; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; FDA, Food and Drug Administration.

Patient Eligibility for Cabozantinib

Cabozantinib was approved by EMA in September 2018 and by FDA in January 2019 “for the treatment of HCC in adults who have previously been treated with sorafenib”. The approval was based on the results of the CELESTIAL trial, with inclusion criteria restricted to patients in good general condition PS 0 or 1, and with a normal liver function Child-Pugh class A. There is no data available in patients with impaired liver function Child-Pugh B or C, neither in patients that have a PS ≥ 2. Therefore, cabozantinib should not be prescribed in these situations.

In elderly patients over 65 years, cabozantinib is safe and effective, according to a sub-analysis of the CELESTIAL study.18 Median OS and PFS in the subgroup of patients over 65 years were improved in the cabozantinib arm compared to placebo, with, respectively, an HR of 0.74 (95% CI 0.56–0.97) and 0.46 (95% CI 0.35–0.59). Elderly patients received subsequent anticancer therapy after progression on cabozantinib in 22% of cases compared to 28% in patients less than 65 years, therefore, suggesting that cabozantinib did not significantly alter quality of life in older patients. Concerning toxicity, the proportion of patients with AEs of grade 3 or 4 was similar between patients less than 65 years and more than 65 years (67% vs 68%). Similarly, the rate of dose reductions and median average daily dose were similar in both age groups.

Choosing Between Second Line Therapies

Efficacy

According to the phase 3 RESORCE and CELESTIAL trials, both cabozantinib and regorafenib improve OS and PFS in advanced HCC. A matching adjusted indirect comparison (MAIC) of these two drugs was performed in patients who received sorafenib as the only prior systemic therapy, and results were reported at the Annual Conference of International Liver Cancer in September 2019.19 Individual patient data from both RESORCE and CELESTIAL trials were used, and patients were matched according to baseline characteristics (age, race, PS, Child-Pugh class, duration of prior sorafenib, extrahepatic disease, macrovascular invasion, AFP level). There was no significant difference in median OS between cabozantinib and regorafenib (respectively 11.4 months vs 10.6 months, p=0.3474). Even though PFS seemed to be prolonged with cabozantinib (5.6 months compared with 3.1 months for regorafenib, p=0.0005), bias in a MAIC may still occur due to imbalance in unobserved factors, and it cannot replace a head-to-head randomized controlled trial. Therefore, the choice between cabozantinib and regorafenib cannot be based on efficacy since it is similar.

To our knowledge, there has been no comparison between the two TKIs approved in second line and ramucirumab. Regarding results of the REACH-2 study,7 the median OS of 8.5 months in the ramucirumab group seems inferior to the results of the CELESTIAL and RESORCE trials. However, no conclusions can be drawn as the study population was not the same in the different studies. Additionally, patients included in the REACH-2 trial had baseline AFP ≥ 400ng/mL, which is a subpopulation of patients with a poorer prognosis.

Finally, there has been no head-to-head comparison between cabozantinib, regorafenib and CPIs. Although pembrolizumab has been approved by FDA and has a favorable risk-to-benefit ratio, the lack of scientific evidence of its efficacy in the phase 3 KEYNOTE-240 study8 should limit the prescription; cabozantinib, regorafenib and ramucirumab should be preferred in second line setting.

Previous Tolerance of Sorafenib

It is important to underline that according to the phase 3 RESORCE trial5 that lead to the approval of the drug, regorafenib should only be used in patients who tolerated sorafenib. Tolerance was defined in the study as the use of ≥ 400mg sorafenib daily for at least 20 out of the 28 days before treatment discontinuation. In the SHARP study,3 44% of patients treated with sorafenib required dose adaptations due to AEs. Therefore, nearly half of patients could not be treated with regorafenib in second line. On the other hand, the use of cabozantinib is not restricted to patients who tolerated sorafenib. Therefore in patients that did not tolerate prior sorafenib, cabozantinib should be preferred over regorafenib in second line.

Time to Progression on Sorafenib

Time to progression on sorafenib is an important factor to take into account to choose between the different treatment options available in second line. In the RESORCE study,5 patients had received only one prior systemic treatment, and median time on sorafenib was 7.8 months in the regorafenib arm; 60% of patients received a full dose of sorafenib (800mg daily) as the last dose before inclusion in RESORCE. An analysis of time to progression (TTP) in the RESORCE trial according to TTP during prior sorafenib was performed.20 Patients were divided into four subgroups according to their quartile of TTP on prior sorafenib. Although the benefit of regorafenib compared to placebo was consistent among the four subgroups, the magnitude of clinical benefit seemed more important in patients that had a longer TTP during sorafenib treatment (patients in the fourth quartile) with a median TTP of 4.5 months (HR 0.54) vs 2.8 months (HR 0.66) in patients rapidly progressive (first quartile).

Meanwhile, a sub-analysis of patients that had received sorafenib as the only prior systemic therapy in the CELESTIAL study were presented at ASCO meeting 2018.15 Median duration of sorafenib was 5 months in the cabozantinib group. OS and PFS according to the duration of prior sorafenib were analysed. In patients who had received sorafenib less than 3 months (rapidly progressive), median OS in the cabozantinib arm was 8.9 months vs 6.9 months with placebo (HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.47–1.10). On the other hand, patients who had received sorafenib for at least 6 months had an OS of 12.3 months with cabozantinib vs 9.2 months with placebo (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.58–1.16). Cabozantinib, therefore, improved OS irrespectively to duration of prior sorafenib treatment. These results suggest that cabozantinib could be preferred over regorafenib in patients rapidly progressive on sorafenib.

Safety Profile

The tolerance of the two TKIs approved for the treatment of advanced HCC in second line setting is similar, with drug class related side effects. The most frequent grade 3 and 4 AEs are hypertension, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, fatigue and diarrhea. However, there are some differences in AEs rates. For instance, up to 10% of patients experience grade 3 or 4 diarrhea with cabozantinib, compared to only 3% with regorafenib. Ramucirumab has a different safety profile. In both REACH and REACH-2 trials,7,21 AEs of grade ≥3 occurring in ≥5% of patients were hypertension and bleeding. The safety profiles of the three drugs are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Grade 3/4 Adverse Events

| Cabozantinib | Regorafenib | Ramucirumab | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 17% | 9% | 7% |

| Palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia | 17% | 13% | 0% |

| Hypertension | 16% | 15% | 12.7% |

| Diarrhea | 10% | 3% | 1% |

| Decreased appetite | 6% | 3% | 1% |

| Other | Bleeding 5% |

The choice between second line therapies could be guided by comorbidities of patients, according to the safety profile of each drug. For example, in patients with renal function impairment, considering the risk of dehydration in case of diarrhea, cabozantinib is probably not the most rational choice.

AFP Level

Ramucirumab is the second line treatment with the strongest level of evidence of efficacy in patients with high AFP level. It has demonstrated an improvement in OS compared to placebo following first-line sorafenib in patients with AFP level ≥400 ng/mL in a dedicated study. The biological mechanism explaining the potential association of AFP with efficacy of ramucirumab is uncertain, several hypotheses have been advanced. HCCs are tumors with an important molecular heterogeneity. Molecular classifications based on transcriptome analysis have shown a subclass of HCC (S2) with elevated baseline AFP, associated with poor prognosis. S2 have an over expression of several kinases involved in growth signaling pathways, such as FGFR3, FGFR4, and IGF2 which might increase VEGF/VEGFR-2 pathway activity and affect sensitivity to ramucirumab.

Cabozantinib has also shown its efficacy in the subgroup of patients with high AFP levels. In the CELESTIAL study, even though AFP level was not a stratification factor, 293 patients had baseline AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL, 192 were treated with cabozantinib and 101 with placebo. Both OS and PFS were improved in the cabozantinib arm in this subgroup of patients, with, respectively, an HR of 0.71 (0.54–0.94) and 0.42 (0.32–0.55). Additionally, AFP response and efficacy outcomes in the CELESTIAL trial presented at ASCO 201922 showed that 50% of patients treated with cabozantinib had an AFP response with a 20% decrease in AFP level from baseline at week 8. AFP response was associated with a longer OS (HR 0.61 [95% CI 0.45–0.84]) and PFS (HR 0.55 [95% CI 0.41–0.74]).

Quality of Life

In a post-hoc analysis of the CELESTIAL trial, QoL with cabozantinib compared to placebo was reported.23 During the initial treatment period (up to week 5 after initiation of the drug), cabozantinib was associated with a small reduction in health utility compared to placebo. After this early deterioration, and particularly after day 150, the difference in QoL favored cabozantinib over placebo (p < 0.001), suggesting that dose adjustments increase tolerability and therefore quality of life. However, considering that median PFS with cabozantinib is 5.1 months, the discreet improvement of QoL with cabozantinib concerns less than 50% of patients treated, as half of them have stopped the drug before day 150 for progression.

Concerning regorafenib, no clinically relevant differences were noted in QoL between regorafenib and placebo groups.5 Even though the total score of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Hepatobiliary (FACT-Hep) was statistically lower in the regorafenib group than the placebo group, minimally important differences thresholds established in the literature were not met.

Finally, patient-reported outcomes assessed with a self-administered questionnaire, were analyzed in the REACH-2 study.7 Ramucirumab demonstrated an increased delay to deterioration in QoL compared to placebo with, respectively, a time to deterioration of 3.7 months vs 2.8 months, with no statistically significant difference however (HR 0.799, p = 0.238). It is the only drug in the second line setting with a favorable QoL profile, which is a considerable advantage in this fragile population.

Cost Effectiveness

Although there is an urgent need for effective therapy in advanced HCC, price of anticancer drugs can limit the accessibility to treatment in some countries. Several studies have focused on the cost effectiveness of cabozantinib;24 only direct medical costs were taken into account (price of cabozantinib, management of AEs). Quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), which is a measure of disease burden, were calculated. Cost effectiveness was measured with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). The ICER of cabozantinib vs placebo according to the outcomes in the CELESTIAL trial was 833 497$ in the USA, 304 177$ in the UK and 156 437$ in China, higher than the willingness to pay thresholds. Similarly, in a second study,25 cabozantinib originated a gain of 0.16 QALYs; the ICER compared to placebo was 469 374$. This suggests that cabozantinib is not cost-effective at its current price.

Similarly, in dedicated studies, neither regorafenib26,27 or ramucirumab28 were cost-effective treatments.

MET Expression

c-MET is a tyrosine kinase receptor to which hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) binds with high affinity, allowing the activation of multiple downstream cascades such as PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways, inducing angiogenesis, cell proliferation, invasion and survival. In preliminary studies, it has been shown that acquired resistance to long-term sorafenib treatment involves upregulation of HGF secretion and c-MET activation.29 In vitro, cabozantinib is able to inhibit tumor growth in HCC cells that overexpress c-MET.30 Moreover in experimental metastatic mouse models, cabozantinib reduced the number of metastatic lesions. Therefore, by inhibiting MET in addition to VEGFR, cabozantinib targets multiples pathways which may provide additional efficacy and help overcome resistance to drugs that target only VEGFR. This hypothesis was not confirmed however in an exploratory analysis of the CELESTIAL study, where outcomes (OS and PFS) were analysed according to plasma biomarkers.31 Plasma samples were collected from 674 patients at baseline and at week 4. Low levels of MET and HGF were associated with a better prognosis, but neither MET expression or HGF level were predictive of an OS benefit with cabozantinib. However, plasma level of c-MET is probably not the best way to assess activation of the c-MET pathway. Immunohistochemistry or more likely bio-molecular data (c-MET amplification) would be preferable to determine a relationship between the efficacy of cabozantinib and activation of the c-MET pathway. However, considering the lack of data confirming c-met amplification as a predictive marker of cabozantinib efficacy, treatment decision according to c-met expression cannot be recommended.

Perspectives

Recently, combinations of CPIs with anti-angiogenic agents have been developed. The most advanced is the association of atezolizumab and bevacizumab which has shown in first line setting an improvement of OS, PFS and a delayed deterioration of QoL compared to sorafenib.10 In light of these encouraging results, there should be a change in international guidelines for the treatment of advanced HCC in first line setting very soon; FDA and EMA approvals are pending. Other combinations are being studied in first line in ongoing phase 3 trials, such as the association atezolizumab/cabozantinib (COSMIC trial) and the association durvalumab/tremelimumab (HIMALAYA study). Results should be available in 2021.Therefore, in the future, all the data available on TKIs will be difficult to interpret, as nearly all TKIs have been tested in patients progressive after a first line therapy with sorafenib. It is difficult to predict the place of cabozantinib in the next years: in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors, or in second line after failure of the combination atezolizumab with bevacizumab?

Conclusion

Cabozantinib is an approved, effective and safe drug for the treatment of advanced HCC in second and third line setting. It should be considered only in patients in good general condition (PS 0 or 1), with a preserved liver function (Child-Pugh class A), regardless to age. After progression on sorafenib, it could be preferred over regorafenib in patients rapidly progressive after first-line, or in case of intolerance to sorafenib. Its safety profile should be taken into account in treatment decision, considering the high proportion of patients experiencing grade 3 or 4 diarrhea. In the future, cabozantinib could be available in fist line setting in combination with CPI, results of the phase 3 COSMIC trial are eagerly awaited.

Funding Statement

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Disclosure

Audrey Debaillon Vesque reports lecture fees and travel fees from Bayer and Ipsen. She also reports personal fees from Bayer, Ipsen, and Roche, outside the submitted work. Jean-Frédéric Blanc reports advisory board and personal fees from Bayer, Ipsen, Eisai, BMS, MSD, Roche, Amgen, Abbvie and advisory board from Lilly. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piscaglia F, Svegliati‐Baroni G, Barchetti A, et al. Clinical patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a multicenter prospective study. Hepatology. 2016;63(3):827–838. doi: 10.1002/hep.28368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llovet JM, Hilgard P, de Oliveira AC, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10126):1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):56–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng A-L, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced and progressing hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1717002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu AX, Kang Y-K, Yen C-J, et al. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased α-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(2):282–296. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30937-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finn RS, Ryoo B-Y, Merle P, et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: a randomized, double-blind, Phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2019;38(3):193–202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yau T, Park JW, Finn RS, et al. CheckMate 459: A randomized, multi-center phase III study of nivolumab (NIVO) vs sorafenib (SOR) as first-line (1L) treatment in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC). Ann Oncol. 2019;30:v874–v875. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz394.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng A-L, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. LBA3 - IMbrave150: efficacy and safety results from a ph III study evaluating atezolizumab (atezo) + bevacizumab (bev) vs sorafenib (Sor) as first treatment (tx) for patients (pts) with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Ann Oncol. 2019;30:ix186–ix187. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz446.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yakes FM, Chen J, Tan J, et al. Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10(12):2298–2308. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurzrock R, Sherman SI, Ball DW, et al. Activity of XL184 (Cabozantinib), an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(19):2660–2666. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelley RK, Verslype C, Cohn AL, et al. Cabozantinib in hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a phase 2 placebo-controlled randomized discontinuation study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(3):528–534. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelley RK, Ryoo B-Y, Merle P, et al. Outcomes in patients (pts) who had received sorafenib (S) as the only prior systemic therapy in the phase 3 CELESTIAL trial of cabozantinib (C) versus placebo (P) in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15_suppl):4088. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.4088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2017;389(10088):2492–2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): a non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(7):940–952. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30351-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rimassa L, Cicin I, Blanc J-F, et al. Outcomes based on age in the phase 3 CELESTIAL trial of cabozantinib (C) versus placebo (P) in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15_suppl):4090. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.4090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelley RK, Mollon P, Blanc JF, et al. Matching-adjusted indirect comparison of cabozantinib versus regorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. P021, ILCA; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finn RS, Merle P, Granito A, et al. Outcomes of sequential treatment with sorafenib followed by regorafenib for HCC: additional analyses from the phase III RESORCE trial. J Hepatol. 2018;69(2):353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu AX, Park JO, Ryoo B-Y, et al. Ramucirumab versus placebo as second-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma following first-line therapy with sorafenib (REACH): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):859–870. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00050-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelley RK, Rimassa L, Ryoo B-Y, et al. Alpha fetoprotein (AFP) response and efficacy outcomes in the phase III CELESTIAL trial of cabozantinib (C) versus placebo (P) in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(4_suppl):423. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.4_suppl.42330452337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abou-Alfa GK, Mollon P, Meyer T, et al. Quality-adjusted life years assessment using cabozantinib for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC) in the CELESTIAL trial. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(4_suppl):207. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.4_suppl.207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao W, Huang J, Hutton D, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of cabozantinib as second-line therapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2019;39(12):2408–2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shlomai A, Leshno M, Goldstein DA. Cabozantinib for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819878304. doi: 10.1177/1756284819878304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shlomai A, Leshno M, Goldstein DA. Regorafenib treatment for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib-A cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parikh ND, Singal AG, Hutton DW. Cost effectiveness of regorafenib as second-line therapy for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2017;123(19):3725–3731. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng H, Qin Z, Qiu X, Zhan M, Wen F, Xu T. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ramucirumab treatment for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib with α-fetoprotein concentrations of at least 400 ng/mL. J Med Econ. 2020;23(4):347–352. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2019.1707211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Firtina Karagonlar Z, Koc D, Iscan E, Erdal E, Atabey N. Elevated hepatocyte growth factor expression as an autocrine c-Met activation mechanism in acquired resistance to sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Sci. 2016;107(4):407–416. doi: 10.1111/cas.12891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiang Q, Chen W, Ren M, et al. Cabozantinib suppresses tumor growth and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma by a dual blockade of VEGFR2 and MET. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(11):2959–2970. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rimassa L, Kelley R, Meyer T, et al. 678PDOutcomes based on plasma biomarkers for the phase III CELESTIAL trial of cabozantinib (C) versus placebo (P) in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC). Ann Oncol. 2019;30:v257–v258. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz247.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]