Dear Editors,

The infection by the 2019 novel coronavirus affects mainly the respiratory system with a variable clinical presentation, from a flu-like syndrome with mild respiratory symptoms to a viral pneumonia with acute respiratory insufficiency, multiple organ dysfunction and death. Recent studies suggest that patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection may have a hypercoagulable state that could predispose to thrombotic events. We describe a patient with COVID-19 who developed an acute portal vein thrombosis.

Case presentation

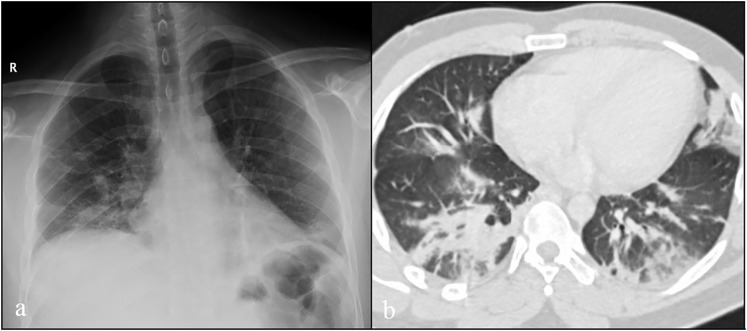

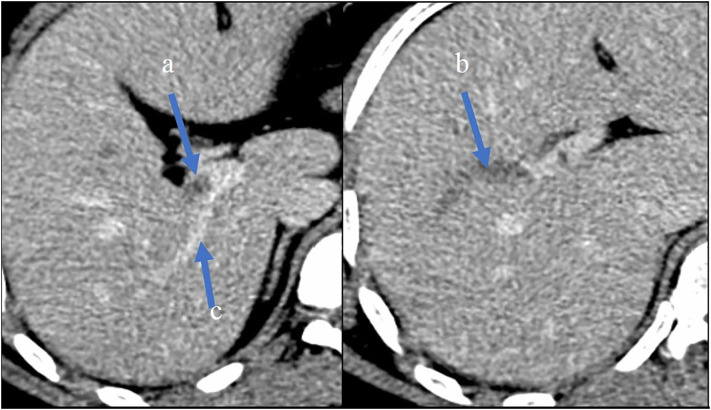

A 27-year-old man from Dominican Republic, with no past medical or surgical history, presented to the emergency department in March 2020, with a three days history of severe colic abdominal pain without nausea, vomiting or diarrhoea. Three weeks before admission he had developed fever and dry cough. In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, during those three weeks the patient stayed home self-isolated, with analgesic and antipyretic treatment. In the emergency department, the patient's temperature was 38.8 °C, he had sinus tachycardia with 150 beats per minute, blood pressure 100/75 mm Hg, respiratory rate 15 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 99% on room air. Physical examination showed an alert young man. Chest auscultation revealed bi-basal crackles. His abdomen was non-distended, with tenderness in the right upper quadrant with negative Murphy's sign. No masses or inguinal hernias were appreciated. No signs of deep vein thrombosis in the lower extremities were found on physical examination. Laboratory findings showed elevated serum aspartate aminotransferase 64 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 111 U/L, lactate dehydrogenase 253 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 148 U/L, total leukocyte count 18 × 109/L (85% neutrophils and 8% lymphocytes), platelets 458 × 109/l, serum fibrinogen > 500 mg/dL (normal range [RN] 150–400), D-dimer using Innovance® D-dimer assay 9.530 μg/L (RN < 500) and C-reactive protein 245 mg/L, while total bilirubin, amylase, lipase, BUN, creatinine clearance, sodium, potassium, calcium, total red blood cell count, haemoglobin, haematocrit, international normalized ratio (INR), activated partial thromboplastin (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT) were normal. The chest X-ray showed alveolo-interstitial opacities in both inferior lobes (Fig. 1a). Therefore, a nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 was performed due to COVID-19 suspicion. A thoracoabdominal computed tomographic (TC) scan with intravenous iodine contrast confirmed a non-enhancing filling defect within the lumen of the right branch of the portal vein without other findings (Fig. 2a, b). The lung window showed bilateral consolidations with ground-glass surrounding in both inferior lobes (Fig. 1b). The patient was admitted to the Internal Medicine Department, and anticoagulant therapy with subcutaneous enoxaparin 1 mg/kg twice daily was started as well as hydroxychloroquine 400 mg loading dose followed by 200 mg per day and azithromycin 500 mg daily. RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 was negative. Blood and sputum cultures were negative. Tests for autoimmunity anti-nuclear antibody, anti-double stranded DNA, anti-extractable nuclear antigen, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody antimitochondrial antibody, antismooth muscle antibody and anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody (anti-LKM-1) were negative. Serum complement C3 level was 198 mg/dL (RN 90–180 mg/dL), with normal C4. Tests for infectious aetiology including hepatitis A, B, C, and HIV, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus and herpes simplex virus were negative. BCR-ABL, JAK-2, Factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A mutations were not detected. Hypercoagulability tests including antiphospholipid antibody, C and S proteins, antithrombin and factor VIII levels were normal. Flow cytometric testing for paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria was negative. The patient evolved favourably with progressive clinical improvement. Fever, respiratory symptoms and abdominal pain disappeared 7 days after admission. Repeated chest X-ray showed improvement of the bilateral alveolo-intersticial opacities. The patient was discharged home 10 days after admission with subcutaneous enoxaparin 80 mg twice daily. Four weeks after discharge, Biozek COVID-19 IgG/IgM (BNCP-402) rapid test Cassette based on lateral flow chromatographic immunoassay for the qualitative detection of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in whole blood was performed. Serological test showed positive IgG and negative IgM. Oral anticoagulant therapy with acenocoumarol was started in the outpatient medical consultation. The duration of anticoagulant therapy for portal vein thrombosis will be kept for 6 months.

Fig. 1.

Chest radiography in postero-anterior projection with lower zone predominant bilateral airspace opacities (a). CT image (lung window) shows bilateral consolidations with ground-glass surrounding in both inferior lobes (b).

Fig. 2.

Abdominal CT in portal phase showing partial non-opacification of portal vein (a) and complete filling defect of the anterior branch of right division (b). Normal opacification of posterior branch (c).

Discussion

Coagulation abnormalities in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection suggest a hypercoagulable state and are consistent with clinical observations of an increased risk of venous thrombosis associated with COVID-19 [1]. In a series of patients with COVID-19, 71.4% of non-survivors met criteria of disseminated intravascular coagulation versus 0.6% of survivors [2]. The pathophysiology of hypercoagulability in COVID-19 is not completely understood. In sepsis the inflammatory response drive fibrin formation and deposition multiple pathogenetic mechanisms are involved, including activation of macrophages, monocytes, platelets and lymphocytes, activation of complement cascade, endothelial dysfunction, Toll-like receptor activation and tissue-factor (TF) pathway activation [3]. The increased expression of TF plays a pivotal role in the activation of blood coagulation in the setting of sepsis. The TF-FVIIa complex activates both FIX to FIXa and FX to FXa. This leads to the formation of thrombin, which induced conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. Based on the bidirectional relationship between the immune system and thrombin generation, the inhibitory effect of heparin on thrombin could reduce the endothelial injury. These anti-inflammatory properties of heparin, could be relevant in this setting [4,5]. Furthermore, observational studies suggest that heparin treatment in COVID-19 pneumonia with D-dimer level > 3.000 μg/L (>6-fold upper normal limit) could be associated to a decrease in mortality [5]. Acute pulmonary embolism [6], acute limb ischemia [7] and acute stroke [8] have been reported in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Recently, Barry et al., have published a portal vein thrombosis in COVID-19 patient [9]. Taking into account that venous thromboembolism is the most thrombotic event reported in patients with COVID-19, venous thrombosis at unusual sites should be considered.

On the other hand, portal vein thrombosis usually occurs in association with cirrhosis, liver malignancy or in patients with inherited or acquired thrombophilia. Portal vein thrombosis due to viral infection is a rare complication. In our patient, secondary causes for hypercoagulable state such as myeloproliferative neoplasms, antiphospholipid syndrome, paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria, deficiencies of proteins C, S and antithrombin, Factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A mutations were excluded, as well as local predisposing factors such as omphalitis, pancreatitis, diverticulitis, and cholecystitis.

According to several recent studies [[6], [7], [8], [9]], our case could suggest that COVID-19 increases the risk of systemic thrombosis. Guidelines recommend prophylactic doses of low-molecular-weight (LMW) heparin to prevent venous thromboembolism (VTE) in all hospitalized patients with COVID-19, unless there is a contraindication to anticoagulation [1]. Nevertheless, the question of whether outpatients with COVID-19 should receive thromboprophylaxis remains to be elucidated. Some guidelines report this may also be appropriate for selected individuals with thrombotic risk factors such a prior VTE episode, immobilization, recent surgery or malignancy [10]. However, our patient developed a vein thrombosis despite not having any thrombotic risk factors. In conclusion, further investigations are necessary to elucidate if outpatients with COVID-19 should receive prophylactic doses with LMW heparin to prevent thrombotic events.

The patient has provided his written informed consent for the publication of this manuscript.

Funding

No specific funding was received from any bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bikdeli B., Madhavan M.V., Jimenez D., Chuich T., Dreyfus I., Driggin E. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. (pii: S0735-1097(20)35008-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang N., Li D., Wang X., Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18:844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keragala C.B., Draxler D.F., McQuilten Z.K., Medcalf R.L. Haemostasis and innate immunity - a complementary relationship: a review of the intricate relationship between coagulation and complement pathways. Br. J. Haematol. 2018;180:782–798. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thachil J. The versatile heparin in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. Apr 2 2020 doi: 10.1111/jth.14821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang N., Bai H., Chen X., Gong J., Li D., Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020 May;18(5):1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., van der Meer N.J.M., Arbous M.S., DAMPJ Gommers, Kant K.M. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. (pii: S0049-3848(20)30120-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y., Cao W., Xiao M., Li Y.J., Yang Y., Zhao J. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID-2019 pneumonia and acro-ischemia. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. Mar 28 2020;41(0):E006. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2020.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y., Xiao M., Zhang S., Xia P., Cao W., Jiang W. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 Apr 23;382(17) doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barry O., Mekki A., Diffre C., Seror M., El Hajjam M., Carlier R.Y. Arterial and venous abdominal thrombosis in a 79-year-old woman with COVID-19 pneumonia. Radiol. Case Rep. 2020 Apr 29 doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2020.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emert R., Shah P., Zampella J.G. COVID-19 and hypercoagulability in the outpatient setting. Thromb. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]