Significance

Globalization and immigration expose people to increased diversity, challenging them to think in new ways about new people. Yet, scientists know little about how changing demography affects human mental representations of social groups, relative to each other. How do mental maps of stereotypes differ, with exposure to diversity? At national, state, and individual levels, more diversity is associated with less stereotype dispersion. Paradoxically, people produce more-differentiated stereotypes in ethnically homogeneous contexts but more similar, overlapping stereotypes in diverse contexts. Increased diversity and decreased stereotype dispersion correlate with subjective wellbeing. Perhaps human minds adapt to social diversity, by changing their symbolic maps of the array of social groups, perceiving overlaps, and preparing for positive future intergroup relations. People can adjust to diversity.

Keywords: intergroup relations, social diversity, perceived similarity, stereotypes, cognitive process

Abstract

With globalization and immigration, societal contexts differ in sheer variety of resident social groups. Social diversity challenges individuals to think in new ways about new kinds of people and where their groups all stand, relative to each other. However, psychological science does not yet specify how human minds represent social diversity, in homogeneous or heterogenous contexts. Mental maps of the array of society’s groups should differ when individuals inhabit more and less diverse ecologies. Nonetheless, predictions disagree on how they should differ. Confirmation bias suggests more diversity means more stereotype dispersion: With increased exposure, perceivers’ mental maps might differentiate more among groups, so their stereotypes would spread out (disperse). In contrast, individuation suggests more diversity means less stereotype dispersion, as perceivers experience within-group variety and between-group overlap. Worldwide, nationwide, individual, and longitudinal datasets (n = 12,011) revealed a diversity paradox: More diversity consistently meant less stereotype dispersion. Both contextual and perceived ethnic diversity correlate with decreased stereotype dispersion. Countries and US states with higher levels of ethnic diversity (e.g., South Africa and Hawaii, versus South Korea and Vermont), online individuals who perceive more ethnic diversity, and students who moved to more ethnically diverse colleges mentally represent ethnic groups as more similar to each other, on warmth and competence stereotypes. Homogeneity shows more-differentiated stereotypes; ironically, those with the least exposure have the most-distinct stereotypes. Diversity means less-differentiated stereotypes, as in the melting pot metaphor. Diversity and reduced dispersion also correlate positively with subjective wellbeing.

To love, to laugh, to live, to work, to fail, to despair, to parent, to cry, to die, to mourn, to hope: These attributes exist whether we are Vietnamese or Mexican or American or any other form of classification. We share much more in common with one another than we have in difference.

Viet Thanh Nguyen (ref. 1)

Nguyen is not alone in contemplating diversity. Globalization and immigration are exposing people to more diversity than ever. There are 272 million immigrants around the world (2): 31% reside in Asia, 30% in Europe, 26% in the Americas, 10% in Africa, and 3% in Oceania. These demographic changes transform economies (3), cultures (4), policy decisions (5), and daily interactions (6). The increasing social diversity challenges individuals, both those who move to a new country and those who host incomers, to think in new ways about new groups of people. However, our knowledge on this topic is incomplete.

Psychological science tells us individuals prefer homogeneity (7). At an interpersonal level, people show homophily, that is, they are attracted to others perceived as similar to themselves (8, 9). At the group level, individuals favor ingroup members, over outgroups, even when ingroup similarity has little meaning (10). Moreover, people tend to approach dissimilar others (outgroups) with uncertainty and vigilance (11). Therefore, people may react negatively toward increasing social diversity. For example, interactions with outgroups produce stress and anxiety (12), and people living in recently integrated, ethnically diverse communities have lower levels of trust and social cohesion (13). From this perspective, the future of diversity seems bleak.

However, recent evidence suggests the opposite: People adapt to diversity. Time helps. In early stages, diversity tends to lower trust, but, with time, mixing with others counteracts that negative affect (14). Initial contact with outgroups is stressful, but, as contact continues, positive outcomes emerge (15). Integration helps. High minority-share areas improve relations between integrated groups but harm relations between segregated groups (16). In diverse communities, it is the residential segregation, not diversity per se, that reduces trust (17). Contact helps. Constructive intergroup contact improves intergroup attitudes (18, 19; but see ref. 20).

How do individuals transition from a predisposition favoring homogeneity, to embrace positive outcomes of diversity? We offer a social cognitive perspective. Humans’ ability to navigate in social environments depends on their mental maps of societal groups (21). As thinking organisms (22, 23), people have attitudes and behavior that depend on their constructions of social reality (24, 25). In prior work, attitudes, affect, and subjective wellbeing demonstrate diversity effects but leave open the cognitive mechanisms. We know people mentally array racial and social class groups on economic status (26, 27), and we know that people map the full array of society’s salient groups on two or more dimensions (21). But we do not know how human minds represent the variety of societal groups under differing degrees of diversity (4, 6)—that is, how they map more and less heterogenous arrays of group stereotypes.

Stereotypes mentally represent social groups, influenced by immediate contexts (28–31). In a homogenous environment, people do not encounter difference, so they can maintain the culturally given stereotypes of outgroups that they rarely see. Diverse environments, compared to homogeneous ones, are more likely to expose people to variety, so they will encounter stereotype-(in)consistent instances and may revise prior stereotypes (32–34). This view of diversity suggests cognitive adaptation to heterogenous environments. Two potential and distinct pathways could describe how stereotype maps adapt under diversity.

The most intuitive of these pathways is confirmation bias: namely, that people seek, infer, and store stereotype-consistent information (35). This suggests more stereotype dispersion, so that socially diverse contexts should reinforce people’s expectations, as they cognitively support their prior stereotypes. In a multidimensional mental space, groups would move farther away from one another, reflecting the distinct stereotypes. People do selectively perceive, learn, and recall group attributes that confirm their prior stereotypes (36); more stereotype dispersion might result from diversity, at least initially.

Although seemingly less plausible, the opposite may also emerge: An individuation perspective (33, 37) might predict less stereotype dispersion with more diversity. In a socially diverse context, individuals begin to reject categorical thinking, as they realize that each category is heterogeneous, comprising many individuals with different characteristics. Exposure to diversity over time would lead to acknowledging more variability and therefore create more overlapping representations of group stereotypes. In a multidimensional mental space, groups move close to one another with overlapping stereotypes. The more overlap, then the more groups seem similar.

To be sure, the pathway of increased stereotype dispersion may fit the initial stage of diversity encounters: The few new, personally unfamiliar groups might seem—without any information except their presumed fit to cultural stereotypes—to support distinct group differences. Homogeneity should, paradoxically, produce differentiated stereotypes. Exaggerated differences may lead to negative outgroup evaluations, increase intergroup anxiety, prevent intergroup contact, decrease social trust, and undermine cohesion; these negative responses, however, may just describe initial responses to diversity (14).

In contrast, decreased stereotype dispersion may be more in line with a positive association between social diversity and intergroup relations over time. Acknowledging the variety within each social category should make their between-group overlap—and therefore similarity—more salient. Diversity should, paradoxically, shrink the dispersed stereotype map, as in the melting pot metaphor. Reducing perceived differences between groups should pave the way for some common ground, easing communication and soothing antagonisms. Subjective wellbeing and more positive responses characterize exposure to diversity—4 y to 8 y after an initial diversity dip in wellbeing, when diversity first increases (14).

To further understand the relevance of stereotype dispersion, we explored its association with group evaluations and general wellbeing. Stereotypes of outgroups are typically negative relative to the mental representation of one’s ingroup. We wanted to know whether reduced perceived dispersion lead to more favorable stereotypes, or simply become similarly more negative or neutral. Moreover, we wanted to know whether stereotype dispersion plays a role in general attitudes toward life satisfaction, given the context of increasing diversity.

Variables

Key variables are defined and operationalized in the following ways.

First, ethnicity is the exemplar domain, given that changes in ethnic diversity shape the world and have been key in recent events, both political (e.g., the refugee crisis, the rise of populist right-wing parties) and historical (e.g., Nazi persecution and genocide of minority groups). We rely on official records of resident ethnicities.

Next, we approximate contextual diversity with the Herfindahl index (38), which measures degrees of group concentration when individuals are classified into groups. Specifically, ethnic diversity (ED) is defined as the probability that two randomly selected individuals from a population will belong to different ethnic groups (39),

| [1] |

where, is the share of ethnic group i in population entity j. It takes into account the relative size distribution of each ethnic group and approaches maximum when a region is occupied by a single ethnicity. Subtracting from 1, then higher scores indicate less concentration of any particular ethnic group, and thus higher diversity. Given that contextual diversity is a distal measure of individuals’ surrounding context, we complement with perceived (proximal) diversity whenever feasible. Perceived diversity is accessed through a self-report of perceived diversity and estimations of groups’ perceived population share.

To differentiate the array of social groups, we approximate their mental representation using the stereotype content model (SCM) (21). Human minds frequently represent various social groups along two central dimensions: warmth and competence. Stereotypes are accidents of history, which result from a group’s perceived societal status (competence) and perceived cooperation/competition (warmth), reflecting the niches of both newly arrived immigrant groups and established long-term inhabitants (40). For instance, current American societal stereotypes portray Canadians and middle-class Americans as warm and competent; Asians and Jews as competent but cold; some native peoples as warm but incompetent; and LatinX refugees as cold (untrustworthy) and incompetent (41). To reflect degrees of stereotype dispersion in this space, we need to measure perceived (dis)similarities among groups. Stereotype dispersion (SD) is operationalized as the Euclidean distance in warmth−competence space,

| [2] |

where is perceived warmth and is perceived competence for each group i; is the centroid, a hypothetical average of warmth and competence, for each population entity j. The Euclidean norm, summing up all Euclidean distances from each group to the centroid and averaging the sum by the number (n) of groups, gives us a dispersion metric. Higher scores indicate larger distances among groups, which means larger stereotype dispersion or more perceived dissimilarities.

Finally, a range of datasets here supports the scope and generalizability of this research. Study 1 focuses on worldwide data, 46 nations on six continents, aggregated from 6,585 respondents. Study 2 collects new data from 50 US states, comprising 1,502 American online respondents. Both studies examine the diversity and dispersion relation. Study 3 examines changes in perceived diversity and dispersion with a 5-y longitudinal study, including 3,924 college students enrolled in 28 American universities. These three studies test our hypothesis at multiple levels (i.e., at the country, state, and individual level) and deploy various analysis strategies (i.e., exploratory, confirmatory, multilevel modeling, and difference-in-difference estimation). Consistently, with ethnic diversity, less stereotype dispersion emerged: Increased contextual and perceived diversity associates with decreased stereotype dispersion, as if social diversity brings together dispersed stereotypes. Moreover, some evidence indicates that increased perceived diversity and decreased stereotype dispersion correlated with more positive group evaluations and increased subjective wellbeing.

Results

Study 1. Stereotype Dispersion Examined Worldwide: More Ethnic Diversity Correlates with Less Stereotype Dispersion.

The SCM has been studied in multiple contexts, including a total of 46 countries (42–45). We merged and analyzed the stereotype content data in these studies. The final dataset contains 12 Western European countries (Belgium, Denmark, England, Finland, Germany, Greece, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland), 8 Eastern European post-Soviet countries (Armenia, Georgia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Kosovo), 9 Middle East countries (Afghanistan, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Pakistan, Turkey), 6 Asian countries/regions (India, Malaysia, South Korea, Japan, Hong Kong, China), 3 African countries (Kenya, South Africa, Uganda), 2 Southwest Pacific countries (Australia, New Zealand), 2 North American countries besides the United States (Canada, Mexico), and 4 South and Central American countries (Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica, Peru).

In each country, preliminary participants listed up to 20 social groups that they could spontaneously recollect. Other participants rated the most commonly mentioned groups’ perceived competence and warmth on five-point scales. These scores were then combined into a stereotype dispersion measure for each country, using Eq. 2. The ethnic diversity data came from ref. 37 that uses Eq. 1. The analyses were conducted at the country level and, given that countries’ levels of income inequality and national wealth are correlated with stereotype content (27), we controlled for these variables with Gini and GDP indexes provided by the World Bank.

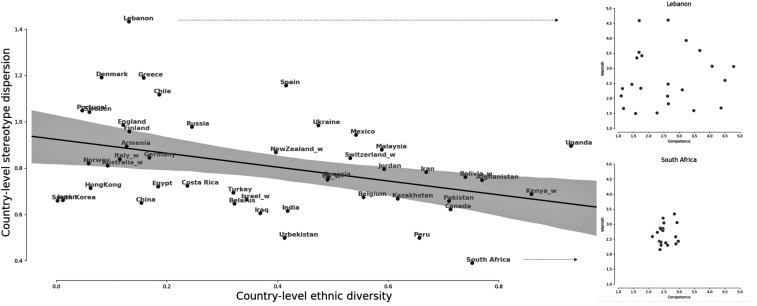

On average, the stereotype dispersion was 0.772 (SD = 0.212). In our sample, South Africa displayed the smallest dispersion (0.391), and Lebanon displayed the largest dispersion (1.433). The average ethnic diversity was 0.371 (SD = 0.260), with South Korea (0.002) representing the least diverse country and Uganda (0.930) representing the most diverse country (see SI Appendix, Table S1 for a full table of country data).

We first explored the Pearson correlation coefficient between countries’ levels of ethnic diversity and social group stereotype dispersion. We observed a negative relationship between ethnic diversity and stereotype dispersion, r(44) = −0.366, P = 0.012. More ethnically diverse nations showed less stereotype dispersion (Fig. 1). Next, adjusting for country-level variables did not change the direction of our results, but including all covariates (Gini and GDP) caused some results to become nonsignificant, r(42) = −0.284, P = 0.062.

Fig. 1.

Inverse linear relationship between ethnic diversity and stereotype dispersion in 46 nations. Note that analysis unit is country or region, n = 46. The x axis indicates contextual ethnic diversity from the most homogeneous (left) to the most diverse (right). The y axis indicates stereotype dispersion from the least dispersed (bottom) to the most dispersed (top) maps in warmth-by-competence space. Each dot represents one country; see Results for statistics. We depict the extreme cases (i.e., Lebanon and South Africa) as clearly illustrating the range of stereotype dispersion. See Results for statistics, and see SI Appendix for maps for each country.

Concentrating on ethnic groups, excluding countries that did not rate multiple ethnic groups, the Pearson correlation again revealed a negative relationship, r(36) = −0.405, P = 0.012. The magnitude was slightly stronger than the test with all social groups. Partial correlation adjusting for country covariates again suggested a negative relationship, r(34) = −0.317, P = 0.060, statistically nonsignificant.

In sum, worldwide data suggest that, the more a country is ethnically diverse, the more participants mentally represent social groups as being close to each other, on warmth and competence dimensions.

Study 2. Stereotype Dispersion from 50 States in the United States: More State-Level and Individual Perceived Ethnic Diversity Predicts Less Stereotype Dispersion.

Study 1 data, collected for other purposes, spanned a 20-y period and were tailored to each society’s particular construction of societal groups, and not just ethnic groups. Limitations thus include generational change from multisite data collection and response heterogeneity from mixed group labels. To address these limitations, we collected data within a single month, from 1,502 online Amazon Mechanical Turk participants distributed across the 50 US states. The United States provides a rich context to test our hypothesis, given its long immigration history. To ensure between-state variability, we used stratified sampling with at least 30 participants from each state (except Nebraska, 13 participants, and North Dakota, 20 participants). In this sample, 42% of the participants were female, with a mean age of 34 y. Most of these participants were married (48%) or single (34%), with some college (28%) or bachelor’s degree (41%). Most said they were descendants of German (25%), British (14%), Native American (10%), or African American (10%) ancestry. All human subjects provided informed consent, and their participation was approved under Princeton University Institutional Review Board #10027.

In this study, participants rated 20 relevant immigrant groups (see Materials and Methods) according to their perceived competence and warmth, on a five-point scale, and we constructed a stereotype dispersion score for each individual using Eq. 2. State-level diversity was calculated using the population proportion of 20 immigrant groups from the US Census data via Eq. 1. Participants also provided their perceived diversity of the state, on a five-point scale (1, almost nobody is of a different race or ethnic group, to 5, many people are of a different race or ethnic group). To reduce omitted variable bias on the state level, we included covariates of Gini and GDP; on the individual level, we included covariates of age, gender, social class (i.e., education, income, social ladder), type of area of residence (i.e., rural or urban), and frequency of contact with other ethnic groups, as well as group identity. As a wellbeing measure, we asked current life satisfaction, on a five-point scale (1, extremely dissatisfied, to 5, extremely satisfied).

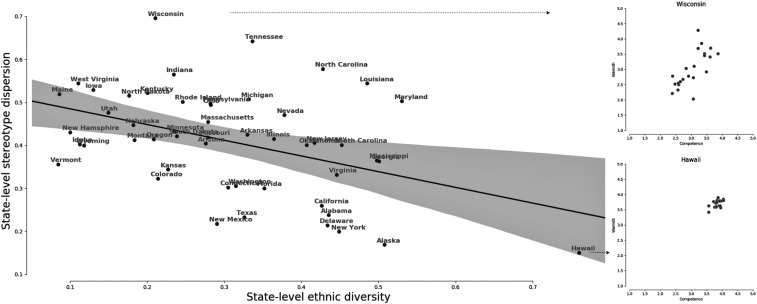

Among 50 states (see SI Appendix, Table S2 for a full table of state data), the average stereotype dispersion was 0.871 (SD = 0.107), with Wyoming showing the largest dispersion (1.079) and Alaska showing the smallest (0.569). On an individual level, the average stereotype dispersion was 0.869 (SD = 0.383), with some showing dispersion as large as 2.449 and some showing 0 dispersion (2.7% of the sample). The average state-level diversity was 0.309 (SD = 0.141). Vermont was the least diverse state (0.085), and Hawaii was the most diverse (0.760). At the individual level, the average perceived diversity was 3.461 (SD = 1.096) on the five-point scale.

First, our analyses started by replicating the study 1 analysis. We tested Pearson correlations between state-level ethnic diversity and state-level ethnic stereotype dispersion. Results confirmed the negative relationship, more diversity less dispersion, r(48) = −0.384, P = 0.006 (Fig. 2). The effect holds after removing an outlier state (i.e., Hawaii), r(47) = −0.305, P = 0.033, or adjusting for state-level Gini and GDP, r(46) = −0.382, P = 0.007.

Fig. 2.

Inverse linear relationship between ethnic diversity and stereotype dispersion in 50 states in the United States. Note that analysis unit is state in the United States, n = 50. The x axis indicates contextual ethnic diversity from the most homogeneous (left) to the most diverse (right). The y axis indicates stereotype dispersion from the least dispersed (bottom) to the most dispersed (top) maps of warmth-by-competence space. Each dot represents one state; see Results for statistics. We depict the extreme cases (i.e., Wisconsin and Hawaii) as clearly illustrating the range of stereotype dispersion. See Results for statistics, and see SI Appendix for maps for each state.

Second, we looked at whether state-level diversity is associated with individual-level stereotype dispersion. We used a multilevel model with errors clustered at the state level. State diversity is the predictor, individual stereotype dispersion is the outcome, and state covariates are controlled. Results showed that state-level diversity predicts individual-level stereotype dispersion (b = −0.282, 95% CI [−0.478, −0.086], P = 0.008): For those living in states with the same levels of inequality and wealth, 1-unit increase in contextual diversity associates with a 0.282-unit decrease in participants’ stereotype dispersion.

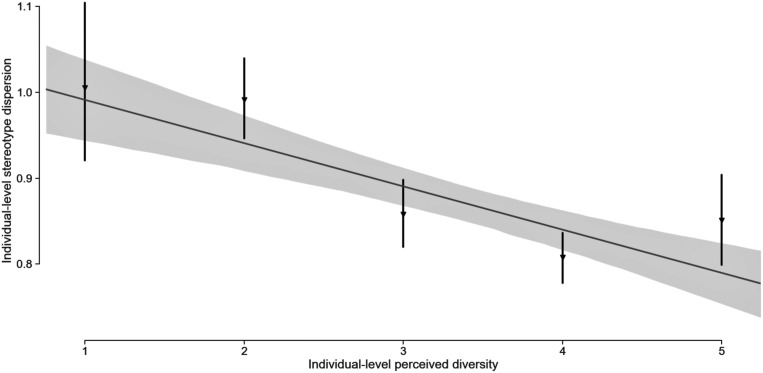

Third, we examined whether individual-level perceived diversity is associated with individual-level stereotype dispersion. We used a multilevel model with errors clustered at state level, individual perceived diversity as the predictor, and individual stereotype dispersion as the outcome, adjusting for individual covariates. Individual-level perceived diversity predicts individual-level stereotype dispersion (b = −0.032, 95% CI [−0.052, −0.012], P = 0.002): Those who perceived more diversity showed less stereotype dispersion; a 1-unit increase in perceived diversity corresponds to a 0.032-unit decrease in stereotype dispersion (Fig. 3; see full model details and robustness checks in SI Appendix, Table S6 and Figs S8 and S9).

Fig. 3.

Individual-level perceived diversity associates with individual stereotype dispersion. Note that analysis unit is online American participants, n = 1,502. The x axis indicates self-report of perceived diversity, ranging from 1, not diverse, to 5, very diverse. The y axis indicates stereotype dispersion from the least dispersed to the most dispersed maps in warmth-by-competence space. Line displays central tendency and 95% CIs for each diversity interval. Full model estimates individual-level linear effects while controlling for within-state dependencies with clustered errors. See statistics in Results.

Next, we explored the mechanisms—that is, how contextual diversity associates with perceived diversity and stereotype dispersion—using mediation analysis (46) (see an alternative mediation analysis in SI Appendix, section 6). Living in diverse states should influence individuals’ perceptions of surrounding diversity, which, in turn, should influence their stereotype dispersion. As expected, the effect of state diversity on stereotype dispersion was fully mediated via perceived diversity: Individuals in diverse states have a tendency to report less stereotype dispersion (b = −0.287, 95% CI [−0.484, −0.089], P = 0.007), but this association was reduced after accounting for perceived diversity (b = −0.164, 95% CI [−0.367, 0.037], P = 0.117). The indirect effect through perceived diversity was a significant mediator (indirect effect b = −0.123, 95% CI [−0.183, −0.064], P < 0.001). This is in line with previous work showing that the psychological effects of perceived diversity tend to be stronger than those of objective measures of diversity (47).

In sum, using a hypothesis-driven controlled survey in 50 states in the United States, we confirmed the inverse relationship between social diversity and stereotype dispersion among 20 top immigrant groups. Contextual diversity at the state level and perceived diversity at the individual level were both associated with decreased stereotype dispersion, with the proximal, perceived indicator being more pronounced, indicating that people mentally represent ethnic groups as being similar on warmth and competence dimensions under diversity.

Study 3. Stereotype Dispersion from a 5-y Longitudinal Study in American Universities: Increased Campus Diversity Is Associated with Decreased Stereotype Dispersion.

The analyses so far revealed that individuals who perceive more ethnic diversity are less likely to mentally differentiate ethnic groups using stereotype content. These analyses were based on cross-sectional data in which the baseline stereotype dispersion can already differ across individuals. We address this problem in this study with a difference-in-difference analysis (48) on a longitudinal dataset examining changes within the same individuals. These analyses were complemented with robustness checks and statistical methods to assess and address potential selection bias in the data.

The analysis rests on a unique panel dataset (49), which contains comparable measures of perceived ethnic diversity and stereotype content when participants graduated from high school in 1999 and then again at the end of their college senior year in 2003. The survey consists of face-to-face interviews in the first wave and telephone interviews in the following four waves. The final sample of 3,924 students contains equally sized racial groups (959 Asian, 998 White, 1,051 African American, and 916 Latino) from 28 higher education institutions, who have lived in a total of 50 different states. In the sample, 58% were female students, and the median household income was $50,000 to $74,999.

The dataset provides measures that are essential to our research question. It includes questions about campus diversity and stereotype content for Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians. Campus diversity is measured by asking the perceived ethnic and racial composition of participants’ high school and college, on a scale from 0 to 100%. We used their responses to calculate perceived diversity via Eq. 1. Stereotype dispersion is measured by perceived competence and warmth of each group. The available items on competence asked about the following: perceived laziness, intelligence, and giving up easily. Warmth was assessed with the following: hard to get along with and honest, on a scale from 1 to 7 (reverse-scoring the negative items). We used these responses to calculate stereotype dispersion via Eq. 2. Note that these questions were only asked in wave 1 (preenrollment) and wave 5 (college senior). As such, we obtained perceived ethnic diversity and stereotype dispersion at these two time points, which were separated by a 4-y time period (see preregistration of this hypothesis online at Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/be9s5). The survey also asked about participants’ life satisfaction (see Materials and Methods), which we used as a wellbeing measure to assess the impact of stereotype dispersion.

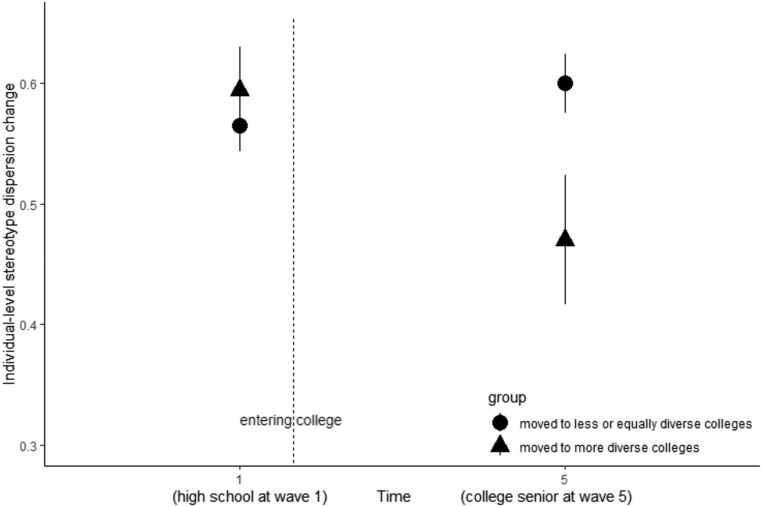

The average stereotype dispersion in high school (M = 0.593, SE = 0.008) was higher than in college (M = 0.562, SE = 0.012), d = −0.031, 95% CI [−0.054, −0.008], P = 0.009. The average perceived diversity in high school (M = 0.446, SE = 0.003) was higher than in college (M = 0.410, SE = 0.005), d = −0.037, 95% CI [−0.046, −0.027], P < 0.001. In high school, perceived diversity did not predict stereotype dispersion (b = −0.001, 95% CI [−0.067, 0.066], P = 0.985), whereas, in college, higher perceived diversity predicted less stereotype dispersion (b = −0.147, 95% CI [−0.246, −0.048], P = 0.004).

To formally model the effect of perceived diversity on stereotype dispersion, we employed a mixed-effects difference-in-difference estimator using the following equation:

| [3] |

where, is the outcome of stereotype dispersion for each individual i at time t. is a dummy time variable that equals 1 for college and 0 for high school; is the continuous treatment variable representing intensity of diversity perceived by each individual i. We interacted and to produce the coefficient which is the average treatment effect of the perceived diversity on stereotype dispersion over time. It measures whether individuals with higher perceived diversity in college experienced a greater decrease in stereotype dispersion from high school to college. is a vector of pretreatment variables including race, gender, and income. The error term is clustered at individual level and high school state level.

We found that the interaction between time and perceived diversity was negative and statistically significant (b = −0.155, 95% CI [−0.260, −0.050], P = 0.004). It indicates a large and significant decrease in stereotype dispersion between high school and college in individuals who perceived more campus diversity. The point estimate implies that 1-unit increase in perceived diversity translated into a 0.155-unit decrease in stereotype dispersion between high school and college (Fig. 4). To adjust for pretreatment individual characteristics, we added gender, household income, and participant’s own ethnicity into the model. These adjustments reduced the perceived diversity coefficient only slightly (b = −0.116, 95% CI [−0.223, −0.009], P = 0.033).

Fig. 4.

Students who attended more diverse colleges show larger decrease in stereotype dispersion from high school to college. Note that analysis unit is American college student, at two time points, n = 3,924. The x axis indicates two time points: end of high school and end of college. The y axis indicates stereotype dispersion change, from less increase to more increase. Error bars in circle represent students who experienced less diversity changes from high school to college, while error bars in triangle represent students who experienced more diversity changes. As shown, students who experienced more diversity changes decreased dramatically in stereotype dispersion, compared to the other group. See statistics in Results.

Next, we checked the robustness of this result. First, campus diversity did not predict placebo outcomes (attitudes toward future, b = −0.014, 95% CI [−0.242, 0.267], P = 0.916, life as failure, b = −0.038, 95% CI [−0.210, 0.135], P = 0.664). Second, campus diversity in elementary school, middle school, and neighborhood were associated with group perceptions similarly as in high school (at 13 y old, b = −0.110, 95% CI [−0.212, −0.007], P = 0.037; three-block radius at 13 y old, b = −0.111, 95% CI [−0.213, -0.009], P = 0.033; at first grade, b = −0.102, 95% CI [−0.203, −0.000], P = 0.049; less so three-block radius at 6 y old, b = −0.090, 95% CI [−0.192, 0.013], P = 0.087). Third, we observed different motivations to move to diverse colleges. Logistic regression suggests that students who thought having enough ingroup members was unimportant were more likely to go to diverse colleges (b = −0.023, 95% CI [−0.043, −0.004], P = 0.020). Although we cannot fully rule out endogeneity, we performed an additional analysis examining the subsample of students who were more open to diversity and moved into a more diverse college. Results were consistent with our previous findings and showed that diversity was negatively associated with stereotype dispersion even among motivated students (b = −0.109, 95% CI [−0.196, −0.021], P = 0.015). See SI Appendix, Fig. S7 and Tables S7–S10 for full model details and missing data adjustments.

In sum, using a quasi-experimental design with longitudinal data among American students, we found that changes in campus diversity were associated with students’ mental representations of ethnic groups. Students who moved to and lived in a more diverse campus perceived more similarities among ethnic groups on warmth and competence stereotype dimensions.

Exploratory Analysis. On the Downstream Effects of Stereotype Dispersion: Less Stereotype Dispersion Associates with Positive Group Evaluations and Higher Life Satisfaction.

Along with the analysis on diversity and stereotype dispersion, we examined two important downstream effects of stereotype dispersion.

First, we found that less dispersed maps tend to cluster groups in the high competence and high warmth quadrant (see SI Appendix, Figs S2, S3, S5, and S6 for visualizations). Groups in diverse contexts are not only perceived as more similar but also are perceived as more positive than neutral. Pearson’s correlations between stereotype dispersion and competence and warmth suggested such positivity effect in cross-country data [stereotype dispersion was negatively correlated with competence, r(44) = −0.315, P = 0.033 and warmth, r(44) = −0.419, P = 0.004; study 1], and cross-state data [competence, r(48) = −0.716, P < 0.001 and warmth, r(48) = −0.724, P < 0.001; study 2]. Multilevel regression with stereotype dispersion as the outcome suggested such positivity effect among online Americans (stereotype dispersion was negatively associated with competence, b = −0.196, 95% CI [−0.225, −0.167], P < 0.001 and warmth, b = −0.224, 95% CI [−0.251, −0.198], P < 0.001; study 2), but not in longitudinal data (stereotype dispersion was positively associated with competence, b = 0.155, 95% CI [0.137, 0.172], P < 0.001 and warmth, b = 0.029, 95% CI [0.015, 0.042], P < 0.001; study 3). Having cross-race friendships was not associated with positivity (higher competence, b = −0.007, 95% CI [−0.051, 0.037], P = 0.763 and warmth, b = 0.026, 95% CI [−0.039, 0.092], P = 0.433; study 3).

Next, we examined the association between stereotype dispersion and life satisfaction. In study 2, using a multilevel model with errors clustered at state level, stereotype dispersion as the predictor, and life satisfaction as the outcome variable, we found an inverse relation (b = −0.147, 95% CI [−0.283, −0.012], P = 0.034). In other words, with a 1-unit decrease in stereotype dispersion, participants self-reported life satisfaction increased by 0.147 units. In two separate models, we found that life satisfaction was positively correlated with perceived diversity (b = 0.110, 95% CI [0.062, 0.159], P < 0.001), but not with state diversity (b = 0.188, 95% CI [−0.235, 0.613], P = 0.389). In study 3, we found that, on aggregate level, less stereotype dispersion was related to more life satisfaction (high school: b = −0.067, 95% CI [−0.128, −0.006], P = 0.031; college: b = −0.080, 95% CI [−0.133, −0.026], P = 0.003; but there were no individual-level effects, interaction term b = −0.044, 95% CI [−0.124, 0.035], P = 0.272). Perceived diversity indeed showed individual-level effects: Within the same individual, increases in perceived campus diversity associated with increases in life satisfaction; interaction term b = 0.228, 95% CI [0.033, 0.423], P = 0.022. In addition, less stereotype dispersion was correlated with other variables, such as positive attitudes toward friends of different races and professors. See SI Appendix, Tables S11–S14 for a full list of these variables and regression results. Having cross-race friendship was correlated with less stereotype dispersion (study 3, b = −0.152, 95% CI [−0.085, −0.005], P = 0.001), adjusting for perceived diversity.

Taken together, these findings suggest that stereotype dispersion might be associated with positive stereotype content and better wellbeing. Although evidence is incomplete, it provides some evidence for a missing link between diversity and evaluations in previous literature. Overall, these results show that stereotype dispersion is not neutral, and, in fact, it may underpin other individual and intergroup outcomes.

Discussion

This research documents mental maps of social groups under diversity, describing the role of social cognition in diversity. Throughout three studies with worldwide, statewide, individual-level, and longitudinal tracking data, we consistently found an inverse relation: more diversity, less stereotype dispersion. Participants in diverse contexts, especially those who report more diversity, evaluated ethnic groups as being more similar on warmth and competence stereotype dimensions. Diversity, paradoxically, reduces perceived group differences. Reduced group differences also correlate with greater subjective wellbeing and with more positive stereotypes in some contexts.

From Homophily to Adaptation.

The changes in mental representations of social groups provide one cognitive condition for the previously mixed findings of responses under diversity. For example, anticipating diversity (6), people initially expect group differences, that is, differentiated stereotypes that elicit threat and negativity toward outgroups. However, as actual diversity increases (6), with more exposure and experience, people may tone down previously exaggerated stereotypes, and start to realize latent and deep commonalities across groups, which eventually buffer against threat and yield more positive group relations over time. Such common ground—reduced stereotype dispersion—is the condition that the contact hypothesis hopes to achieve: the perception of common humanity (ref. 18, p. 281). It is also the condition that Nguyen realized: We share much more in common with one another than we have differences (1). Reduced stereotype dispersion may have created similarity attracting positive interactions (7–9), and this is indicated in our data by associations with positive outcomes.

The current studies provide evidence that diversity is associated with less stereotype dispersion, but they do not specify psychological mechanisms, which should be explored in the future.

Positivity.

We found some evidence showing that less stereotype dispersion relates to positive stereotype content. It is an open question why the single, less-dispersed mental map did not sit in middle−middle position. One possibility suggests norms (50). Diverse environments endorse tolerant norms that lead to more positive outgroup ratings. Another possibility is repeated exposure inducing attraction (51). The higher the exposure to outgroups, the more individuals attach positive affect to these groups, resulting in positive impressions. A third possibility is person positivity (52): Increased familiarity makes outgroups seem more personal and human, which, in turn, should produce more positive evaluations. A fourth possibility is similarity asymmetry (53). The societal ingroup (high-competence/high-warmth quadrant) is the reference group, so outgroup members are perceived to be similar to the societal ingroup, instead of the societal ingroup being similar to outgroups. Future work needs to test these mechanisms.

Process.

Mental maps of social groups’ economic positions differ, especially among individuals who experience different information from local networks and who endorse different motivations (26, 27). Likewise, reduced stereotype dispersion under diversity will differ by experience and motivation.

Experience-updating models (54) would suggest that warmth and competence are abstract knowledge that people learn from initially sparse data and update based on new evidence. New data with low feature variability (as found in a homogeneous society) strengthens prior knowledge, such as larger stereotype dispersion. New data with high feature variability (as found in a diverse society) weakens or adjusts it, which may lead to smaller stereotype dispersion. Intergroup research suggests that people perceive ingroups as more heterogeneous (55), and as less extreme (56) than outgroups. Our result extends the scope by suggesting that extreme evaluations may come from differentiated stereotypes engrained in homogeneous environments, whereas less extreme evaluations may come from overlapping cognitive representations in diverse environments (57). When experiencing diversity, people may also break stereotype-inconsistent exemplars into new subtypes (58). In this context, new subtypes might make it easier to see overlaps across superordinate categories, which should lead to reduced stereotype dispersion. An alternative experience may come from category simplification. As the number of ethnic groups within a society increases, people might experience cognitive load. They could simplify the categories or shift away from immigrant or ethnic categories (59), which could also reduce stereotype dispersion.

Besides experience, motivation-based models (33) would suggest that people who live in diverse contexts want to get along with different others. This orientation toward outgroups, in turn, promotes more thoughtful, deliberate processes. People living in homogeneous contexts do not have such motivations and therefore use relatively automatic stereotypes (a dual-process model; ref. 32). Future work needs to disentangle the mechanisms and specify exactly how diversity reduces stereotype dispersion.

Generality.

Several directions would expand the scope. 1) One direction is assessing stereotype dimensions other than warmth and competence. Recent studies suggest ideological beliefs (60) and other unforeseen spontaneous contents (61) can be critical in impression formation. 2) Another is considering diversity other than ethnicity. Sexual orientation and ideological and religious beliefs are also important socially defined categories. 3) A third direction is examining causality. Demographic changes by themselves may influence mental representation of social groups, but randomized experiments need to substantiate. Experimentally increasing the perceived variability of outgroup members leads to more positive evaluations of those groups (62). Although, according to our reasoning, changes in group perception should be adjusted by continuous exposure (i.e., over a period of time) with large variations (i.e., larger scale), single-time or single-site manipulation can be further improved. 4) Yet another direction is linking cognition and behaviors. More research needs to test how changing mental representation in human minds influences consequential decision-making and action (27, 63).

Variations.

Overall, individuals adapt to increasing diversity in ways that are consonant with the coexistence of multiple groups. Reducing perceived differences between groups facilitates finding common ground and sharing social identity, and aids meaningful intergroup interactions. However, make no mistake: Diverse societies are not free of challenges that hamper the adaptive processes uncovered by our work. More threatening contexts characterized by segregation (16, 17, 49), ethnic conflict (13, 39), or sharp inequalities between ethnic groups (26, 27) can slow down or even curb adaptation to diversity. Majority−minority dynamics may also create variations. Entering a more diverse demography can be very different in terms of power dynamics for people who are historically dominant versus underrepresented minorities. We observed that the association between diversity and stereotype dispersion was not conditional on participant’s group identities (see also SI Appendix, Tables S3–S5). However, one procedural limitation is that we asked about shared societal stereotypes, but not group- or individual-specific opinions. Future work can address this limitation and explore group dynamics around diversity and social cognition.

Our work provides evidence of a possible pathway by which individual cognitions adapt to demographic changes in their social ecologies. The core finding—individuals have in them the potential to embrace diversity—should encourage societies to intervene against potential barriers to a peaceful coexistence. One positive characteristic of social diversity is the broadening of people’s horizons. Ironically, stereotype content maps of relevant groups show the opposite movement (i.e., groups represented in mental maps tend be become compressed together). However, perhaps broadening horizons means realizing that societal groups do not differ as much as individuals may initially imagine. Exposure to diversity teaches that fact.

Materials and Methods

Ethnic Diversity.

In study 1, ethnic diversity data came from ref. 39 dataset. The authors used the Encyclopedia Britannica and Atlas Narodov Mira to get the proportion of different ethnic groups per country, and calculated an index of ethnic diversity using the Herfindahl index (38). In study 2, we used estimates of the proportion of different ethnic groups per state in the United States. We used the US Census (2010) data, the most recent census available. In study 2, this measure was paired with a subjective ethnic diversity measure in which participants responded, on a five-point scale, regarding the state where they live, from 1 “almost nobody is of a different race or ethnic group” to 5 “many people are of a different race or ethnic group.” In study 3, we used estimates of the proportion of different ethnic groups per student per wave, by a perceived ethnic diversity measure available in the survey. In wave 1 (high school) and wave 2 (college), participants responded to the question “What was the ethnic and racial composition of your last high school?” and “Think back to the very first class you attended at college, roughly what percentage of the students were…?” Participants responded to both questions on a scale from 0 to 100 for African Americans, Hispanics or Latinos, Asians, and Whites. A higher score in these measures indicates more ethnic diversity (Eq. 1).

Stereotype Dispersion.

We calculated stereotype dispersion by assessing how different groups were perceived in terms of warmth and competence. In study 1, 6,585 participants (52% female, mean age 27 y old, most had a college degree) read in their native language, “We intend to investigate the way societal groups are viewed by the [country] society. Thus, we are not interested in your personal beliefs, but in how you think they are viewed by others.” These groups were provided by a subset of participants from each country. These groups were different for each country, but commonly mentioned groups were age, gender, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and religious groups. For each of these social groups, participants read, “To what extent do most [country citizen] view members of [that group] as [trait]?” The dimension of warmth was assessed with the following traits: “warm,” “well-intentioned,” “friendly,” “sincere,” and “moral.” Competence was assessed with “competent,” “capable,” and “skilled.” All responses were recorded on a scale from 1 “not at all” to 5 “extremely.” In study 2, we presented participants with the same question as in study 1, but, this time, we selected the groups that were assessed by including the 20 largest immigrant groups in the United States according to the 2016 yearbook of Immigration Statistics. With this criterion, we included the following groups: Mexicans, Germans, British, Italians, Canadians, Irish, Russians, Filipinos, Chinese, Austrians, Indians (from India), Hungarians, Cubans, Dominican Republican, Swedish, Koreans, Vietnamese, Polish, African Americans, and Native Americans. Participants evaluated each group with the traits “warm” and “trustworthy” to assess warmth and the traits “competent” and “assertive” to assess competence. In study 3, respondents read, “Where would you rate [ethnic group] on this scale, where 1 means tends to be [adjective] to 7 means tends to be [adjective].” The groups in the survey were: Asian, White, African American, and Latino. All groups were assessed with the available traits diagnostic of warmth (“hard to get along with” and “honest”) and competence (“hardworking,” “intelligent,” and “stick with it”). Exploratory factor analysis confirmed that items loaded on expected dimensions. Factor loadings were 0.38 for hard to get along with and 0.51 for honesty, while factor loadings were 0.71 for hardworking, 0.64 for intelligent, and 0.59 for stick with it. The survey included other traits, but none of them were diagnostic of either competence or warmth, and thus were not included in our measure (see preregistration). These warmth and competence scores were used to calculate our stereotype dispersion measure. Stereotype dispersion was defined as the Euclidean norm among social groups on a two-dimensional warmth and competence space (Eq. 2).

Wellbeing.

Study 1 does not have wellbeing measures. Study 2 participants responded to the question “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole nowadays?” (1. Extremely dissatisfied, 2. Moderately dissatisfied, 3. Slightly satisfied, 4. Moderately satisfied, 5. Extremely satisfied). Study 3 wave 1 included the item “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.” (1. Strongly agree, 2. Agree, 3. Neither agree or disagree, 4. Disagree). Wave 5 had the item “You enjoyed life.” (0. Never, 1. Rarely, 2. Sometimes, 3. Often, 4. All of the time). Responses were reverse-coded and rescaled to align the two waves to be comparable.

Covariates.

We controlled for variables influencing warmth and competence at both the contextual (studies 1 and 2) and individual (studies 2 and 3) levels. In study 1, we were restricted to the use of aggregated data and could not include individual-level variables. We controlled for income inequalities measured with the Gini and GDP index, provided by the World Bank. We matched these data with each country and the year the data were collected. When Gini data were not available for the exact year, we used the nearest available year.

In study 2, we controlled Gini and GDP at the state level using Bureau of Economic Analysis data. At the individual level, the following covariates were included: age (continuous, centered), gender (binary, factored), education level (from elementary to J.D./M.D./Ph.D., continuous, centered), annual household income (from less than $10,000 to $150,000 or more, continuous, centered), and social status (1. Bottom of the ladder to 9. Top, continuous, centered). To account for characteristics of the different locations, we controlled for type of living area with the following question: “Which of the following best describes the area you live in?” (1. Big city, 2. Suburbs or outskirts of a big city, 3. Town or small city, 4. Village, 5. Farm or home in countryside, continuous, centered; robust check with discrete). To see whether self-report frequency of contact contributes to stereotype dispersion, we controlled: “How often do you have any contact with people who are of a different race or ethnic group when you are out and about? This could be on public transport, in the street, in stores or in the neighborhood.” (1. Never, 2. Once a month or less, 3. Several times a month, 4. Several times a week, 5. Everyday, continuous, centered).

Study 3 was restricted to individual-level data. We controlled for demographic features in the survey: gender (binary, factored), race (categorical, factored), and household income (1. Under $3,000 to 14. $75,000 or more, continuous, centered).

Data and Materials Availability.

All data and analytic code can be accessed at GitHub, https://osf.io/hcg72/?view_only=45a5a582fe2c4ae9af88dc32795c875c. Study 3 preregistered the analysis plan at Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/be9s5.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Princeton University. Part of this research was conducted while M.R.R. was a visiting scholar at Princeton University, funded by a Fulbright Grant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

Data deposition: All data and analytic code can be accessed at GitHub, https://github.com/XuechunziBai/Social-Diversity-Stereotype-Content-Similarity. Study 3 preregistered the analysis plan at Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/be9s5.

See online for related content such as Commentaries.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2000333117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nguyen V. T., The people we fear are just like us. NY Times Op-Docs. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/19/opinion/opdocs-immigration.html. Accessed 19 November 2019.

- 2.United Nations , The international migrant stock. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.asp. Accessed 31 August 2019.

- 3.Milanovic B., Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization, (Harvard University Press, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crisp R. J., Meleady R., Adapting to a multicultural future. Science 336, 853–855 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bansak K. et al., Improving refugee integration through data-driven algorithmic assignment. Science 359, 325–329 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig M. A., Rucker J. M., Richeson J. A., The pitfalls and promise of increasing racial diversity: Threat, contact, and race relations in the 21st century. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 27, 188–193 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caporael L. R., The evolution of truly social cognition: The core configurations model. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 1, 276–298 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrne D., Interpersonal attraction and attitude similarity. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 62, 713–715 (1961). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McPherson M., Smith-Lovin L., Cook J. M., Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 27, 415–444 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tajfel H., Turner J. C., . “An integrative theory of inter-group conflict” in The Social Psychology of Inter-group Relations, Austin W. G., Worchel S., Eds. (Brooks/Cole, Monterey, CA, 1979), pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stephan W. S., Stephan C. W., . “An integrated threat theory of prejudice” in Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination, (Psychology Press, 2013), pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toosi N. R., Babbitt L. G., Ambady N., Sommers S. R., Dyadic interracial interactions: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 138, 1–27 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Putnam R. D., E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century: The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize lecture. Scand. Polit. Stud. 30, 137–174 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramos M. R., Bennett M. R., Massey D. S., Hewstone M., Humans adapt to social diversity over time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 12244–12249 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacInnis C. C., Page-Gould E., How can intergroup interaction be bad if intergroup contact is good? Exploring and reconciling an apparent paradox in the science of intergroup relations. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10, 307–327 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laurence J., Schmid K., Rae J. R., Hewstone M., Prejudice, contact, and threat at the diversity-segregation nexus: A cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis of how ethnic out-group size and segregation interrelate for inter-group relations. Soc. Forces 97, 1029–1066 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uslaner E. M., Segregation and Mistrust: Diversity, Isolation, and Social Cohesion, (Cambridge University Press, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allport G. W., The Nature of Prejudice, (Addison-Wesley, Cambridge, MA, 1954). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pettigrew T. F., Tropp L. R., A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 90, 751–783 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paluck E. L., Green S. A., Green D. P., The contact hypothesis re-evaluated. Behav. Public Policy 3, 129–158 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiske S. T., Cuddy A. J. C., Glick P., Xu J., A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 82, 878–902 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiske S. T., Thinking is for doing: Portraits of social cognition from daguerreotype to laserphoto. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 63, 877–889 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor S. E., Brown J. D., Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychol. Bull. 103, 193–210 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lippmann W., Public Opinion, (Free Press, 1965). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy G. L., Medin D. L., The role of theories in conceptual coherence. Psychol. Rev. 92, 289–316 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraus M. W., Rucker J. M., Richeson J. A., Americans misperceive racial economic equality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 10324–10331 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hauser O. P., Norton M. I., (Mis)perceptions of inequality. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 18, 21–25 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durante F. et al., Nations’ income inequality predicts ambivalence in stereotype content: How societies mind the gap. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 52, 726–746 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durante F. et al., Ambivalent stereotypes link to peace, conflict, and inequality across 38 nations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 669–674 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiedler K., Beware of samples! A cognitive-ecological sampling approach to judgment biases. Psychol. Rev. 107, 659–676 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hogarth R. M., Lejarraga T., Soyer E., The two settings of kind and wicked learning environments. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 24, 379–385 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crisp R. J., Turner R. N., Cognitive adaptation to the experience of social and cultural diversity. Psychol. Bull. 137, 242–266 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiske S. T., Neuberg S. L., . “A continuum of impression formation, from category-based to individuating processes: Influences of information and motivation on attention and interpretation” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Zanna M. P., Ed. (Academic, 1990), Vol. 23, pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmid K., Hewstone M., Ramiah A. A., Neighborhood diversity and social identity complexity: Implications for intergroup relations. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 4, 135–142 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nickerson R. S., Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2, 175–220 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiske S. T., . “Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination” in Handbook of Social Psychology, Gilbert D. T., Fiske S. T., Lindzey G., Eds. (McGraw-Hill, New York, NY, ed. 4, 1998), Vol. 2, pp. 357–411. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brewer M. B., . “A dual process model of impression formation” in Advances in Social Cognition, Srull T. K., Wyer R. S. Jr., Eds. (Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, 1988), Vol. 1, pp. 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirschman A., The paternity of an index. Am. Econ. Rev. 54, 761–762 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alesina A., Devleeschauwer A., Easterly W., Kurlat S., Wacziarg R., Fractionalization. J. Econ. Growth 8, 155–194 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiske S. T., Durante F., . “Stereotype content across cultures” in Handbook of Advances in Culture and Psychology, Gelfand M. J., Chiu C., Hong Y., Eds. (Oxford University Press, 2016), Vol. 6, pp. 209–258. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee T. L., Fiske S. T., Not an outgroup, not yet an ingroup: Immigrants in the stereotype content model. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 30, 751–768 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cuddy A. J. et al., Stereotype content model across cultures: Towards universal similarities and some differences. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 1–33 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kervyn N., Fiske S. T., Yzerbyt V. Y., Integrating the stereotype content model (warmth and competence) and the Osgood semantic differential (evaluation, potency, and activity). Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 43, 673–681 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu S. J., Bai X., Fiske S. T., Admired rich or resented rich? How two cultures vary in envy. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 49, 1114–1143 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grigoryan L. et al., Stereotypes as historical accidents: Images of social class in postcommunist versus capitalist societies. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 46, 927–943 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baron R. M., Kenny D. A., The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koopmans R., Schaeffer M., Relational diversity and neighbourhood cohesion. Unpacking variety, balance and in-group size. Soc. Sci. Res. 53, 162–176 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Angrist J. D., Pischke J. S., Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion, (Princeton University Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Massey D. S., Charles C., National Longitudinal Survey of Freshmen, (Office of Population Research, Princeton University, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christ O. et al., Contextual effect of positive intergroup contact on outgroup prejudice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 3996–4000 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zajonc R. B., Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 9, 1–27 (1968).5667435 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sears D. O., The person-positivity bias. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 44, 233–250 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tversky A., Features of similarity. Psychol. Rev. 84, 327–352 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tenenbaum J. B., Kemp C., Griffiths T. L., Goodman N. D., How to grow a mind: Statistics, structure, and abstraction. Science 331, 1279–1285 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Konovalova E., Le Mens G., An information sampling explanation for the in-group heterogeneity effect. Psychol. Rev. 127, 47–73 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Linville P. W., The complexity–extremity effect and age-based stereotyping. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 42, 193–211 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Linville P. W., Fischer G. W., Salovey P., Perceived distributions of the characteristics of in-group and out-group members: Empirical evidence and a computer simulation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57, 165–188 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park B., Judd C. M., Ryan C. S., Social categorization and the representation of variability information. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2, 211–245 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zuberi T., Bonilla-Silva E., Eds., White Logic, White Methods: Racism and Methodology, (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koch A., Imhoff R., Dotsch R., Unkelbach C., Alves H., The ABC of stereotypes about groups: Agency/socioeconomic success, conservative-progressive beliefs, and communion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 110, 675–709 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nicolas G., Bai X., Fiske S., Automated dictionary creation for analyzing text: An illustration from stereotype content. 10.31234/osf.io/afm8k. Accessed 19 April 2019. [DOI]

- 62.Brauer M., Er-Rafiy A., Increasing perceived variability reduces prejudice and discrimination. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 47, 871–881 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martinez J. E., Feldman L., Feldman M., Cikara M., Narratives shape cognitive representations of immigrants and policy preferences. 10.31234/osf.io/d9hrj (31 December 2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.