Abstract

The palladium-catalyzed, α-selective hydroarylation of acrylates and acrylamides is reported. Under optimized conditions, this method is highly tolerant of a wide range of substrates including those with base sensitive functional groups and/or multiple enolizable carbonyl groups. A detailed mechanistic study was undertaken, and the high selectivity of this transformation was shown to be enabled by the formation of an [PdII(Ar)(H)] intermediate, which performs selective hydride insertion into the β-position of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION.

α-Arylated carbonyl compounds are ubiquitous substructures in organic synthesis, and the diverse bioactivity of such molecules is exemplified by familiar blockbuster drugs, such as Naproxen and Ibuprofen. Traditionally, this structural motif can be prepared using Pd(0)-catalyzed α-arylation of enolates, as pioneered by Buchwald and Hartwig (Figure 1A).1,2 In these systems the reactive nucleophile is generated via in situ deprotonation of carbonyl compounds with strong base or via pre-formation of the corresponding silyl enol ether. Alternatively, cross-coupling-based methods from the corresponding α-halocarbonyl electrophiles have also been described under nickel or palladium catalysis (Figure 1B).1,3

Figure 1.

Previous metal-catalyzed α-arylation methods, and synopsis of this study.

While these methods are highly enabling and can even be performed in an enantioselective fashion through use of an appropriate chiral ligand, they possess inherent limitations. For example, in enolate α-arylation, strong bases such as NaOtBu and LiTMP are required, which can preclude the use of certain functional groups, such as those with racemizable stereocenters, and can introduce site selectivity issues in compounds possessing multiple carbonyl groups. In the case of cross-coupling methodology, the α-halo carbonyl electrophiles must be pre-synthesized and are not always stable. To address these issues, we envisioned an alternative disconnection where the aryl group is installed at the α-position via a palladium-catalyzed hydroarylation reaction of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds.

At the outset we recognized that the envisioned mode of regioselectivity is opposite to what has previously been documented in reductive Heck systems that proceed via a canonical mechanism involving: oxidative addition of [Pd(0)] to the aryl (pseudo)halide to furnish a [PdII(Ar)(X)] intermediate, coordination of the alkene substrate, 1,2-migratory insertion to deliver the aryl moiety to the partially positively charged β-position, and interception of the [PdII(enolate)] with a hydride source.4,5 We imagined that under appropriate conditions, this process could take place in a polarity-inverted fashion via a [PdII(Ar)(H)] species that would undergo hydride insertion into the β-position to access a [PdII(Ar)(enolate)] intermediate that is analogous to that of typical enolate α-arylation methodology (Figure 1C).

[PdII(Ar)(H)] species and progenitor complexes, such as [PdII(Ar)(formate)], have been synthesized and studied in pioneering work by Alper and have been widely invoked as intermediates in palladium-catalyzed hydrodehalogenation chemistry.6,7 Though at first glance it would seem that these intermediates would be prone to immediate Ar–H reductive elimination, a growing body of literature has invoked [M(R)(H)] (R = alkyl or aryl), accessed via C–H oxidative, or less commonly O–H oxidative addition, followed by transmetalation, as key intermediates in alkene addition processes (Figure 1c).8,9

Herein, we describe the successful realization of the blueprint described above, wherein [PdII(Ar)(H)] intermediates are leveraged for alkene additions. This hydroarylation chemistry represents a mild and operationally convenient strategy to form α-arylated products under ambient atmosphere, with water as a co-solvent, using common and commercially available starting materials.

OPTIMIZATION AND SCOPE.

The study began by attempting to optimize the reaction conditions with 1a and 2a as pilot substrates to provide 3a as the product (see Table S1). We found that optimal conditions for hydroarylation were as follows: 2.5% Pd2(dba)3, 20% tris(4-fluorophenyl)phosphane ligand, 2 equiv K3PO4, and 1.5 equiv 30% aqueous tetramethylammonium formate (TMA•HCO2), in dioxane at 80 °C. Under these conditions, >20:1 α:β selectivity was observed, and 3a could be prepared in 90% yield on 0.2 mmol scale and 73% on 10 mmol scale. To summarize key observations, the solubility of the formate salt is critical for maintaining high selectivity for the desired α-hydroarylated product. Formate sources with metallic counterions were inferior to tetramethylammonium, even when used with a phase transfer catalyst, likely due to reduced solubility. Under optimal conditions, the major byproduct arises from reduction of the alkene.

An excess of ligand is necessary for high selectivity observed; with ligand-to-palladium ratios of <2:1, high amounts of β-arylated products were observed (see Figure S11). The origin of this phenomenon could be premature coordination of the alkene to the trans-Ln•PdII(Ar)(I) intermediate, leading to classical polarity Heck-type products. Chelating bidentate phosphine ligands, which could potentially function in their native form or as the monophosphine/monophosphine-oxide,10 are low yielding due to being both cis-coordinating and sterically demanding (see Table S1). We believe that the ligand needs to be of sufficient coordination strength to prevent premature alkene coordination but also labile enough to dissociate in downstream steps. The 4-fluoro-substituent on the triarylphosphine serves to tune the electronic properties of phosphorous to provide this balance in coordination strength, while also being sterically unobtrusive to allow formate to adopt an η3 configuration in the 5-coordinate decarboxylation transition state.6

We next tested the scope and functional group tolerance. Electron-donating and -withdrawing substituents on the aryl iodide were tolerated in the reaction, with electron-withdrawing groups giving consistently higher yields (Figure 2). The reaction is sensitive to steric hindrance, with 2-substituted aryl iodides giving little to no conversion. The reaction is tolerant of heterocycles (3m-s), protected amines (3k), and alcohols (3i, 3l). Moreover, potentially reductively labile groups, including an unprotected aldehyde (3e), a nitro group (3g) a nitrile (3h), and an unprotected ketone (3j), remained intact. Complete selectivity was observed in coupling partners bearing both a br mide and iodide (3d). Next, the reaction was evaluated with different acrylamides and acrylates (Figure 3). The amount of base is critical to the success of these substrates and the reaction was performed with 1% Pd2(dba)3, 5% ligand, and 1 equivalent K3PO4. The reaction performs well with secondary and tertiary amides, tolerating a wide range of heterocycles. The reaction is limited to either monodentate or weakly bidentate amides as no reaction is seen with strongly chelating groups such as 8-aminoquinoline (see Figure S3 for additional limitations). The reaction is also highly compatible with acrylates (5k–5l), presumably because the pKa of the putative enolate is in a similar range to that of the acrylamide substrates.

Figure 2.

Aryl iodide scope. Conditions: 1a (0.20 mmol), 2 (0.24 mmol), Pd2(dba)3 (0.005 mmol), P(4-F-C6H5)3 (0.040 mmol), tripotassium phosphate (0.40 mmol), 30% aq. TMA•HCO2 (0.30 mmol, 0.100 mL), and dioxane (0.133 mL), 80 °C, 4–12 h. Ratios of α:β were determined via 1H NMR (600 MHz) of the crude reaction mixture. Percentages represent isolated yields of the α-arylated product.

Figure 3.

Acrylamide and Acrylate Scope. a Conditions: 4a-l (0.20 mmol), 2a or 2d (0.24 mmol), Pd2(dba)3 (0.002 mmol), tris(4-fluorophenyl)phosphane (0.010 mmol), tripotassium phosphate (0.20 mmol), 30% aq. TMA•HCO2 (0.30 mmol, 0.100 mL), 1,4-dioxane (0.133 mL), 80 °C, 4–12 h. b Conditions: 4n-q (0.20 mmol), 2a (0.24 mmol), Pd2(dba)3 (0.005 mmol), tris(4-fluorophenyl)phosphane (0.050 mmol), tripotassium phosphate (0.40 mmol), TMA•HCO2 (0.30 mmol, 0.100 mL), and 1,4-dioxane (0.133 mL), 100 °C, 24 h. Ratios of α:β were determined via 1H NMR (600 MHz) of the crude reaction mixture. Percentages represent isolated yields of the α-arylated product.

The reaction is not limited to terminal olefin substrates and works with a range of 1,2-disubstituted olefins, albeit with lower conversion. The reaction is compatible with both Z- and E-α,β-unsaturated amides, furnishing the corresponding products in moderate yields and selectivity (5m-q). We believe that mechanistically, hydride and aryl are inserted-syn to one another. Therefore, if the product formed was diastereometic, opposite diastereoselectivity would be observed for E and Z alkene isomers.

To highlight the mild and chemoselective nature of this method, a racemization experiment was performed with amino acid 9. When subjected to the reaction conditions, no loss of enantiomeric excess (ee) was detected (Figure 4). In addition, substrates 4r and 4s were subjected to the reaction conditions and only the hydroarylated products 5r/5s were formed. The potential Buchwald–Hartwig α-arylated byproduct was not detected, showing that it is possible to selectively functionalize one α-carbon over another. In addition, the acetate protecting group, which is labile under basic conditions, was not removed showing this method to have high functional group tolerance. The observed functional group tolerance suggests that this method could be employed in the synthesis of increasingly complex targets, such as millamolecular peptides or bifunctional molecules.

Figure 4.

Examples demonstrating chemoselectivity and functional group compatibility.

MECHANISTIC STUDIES.

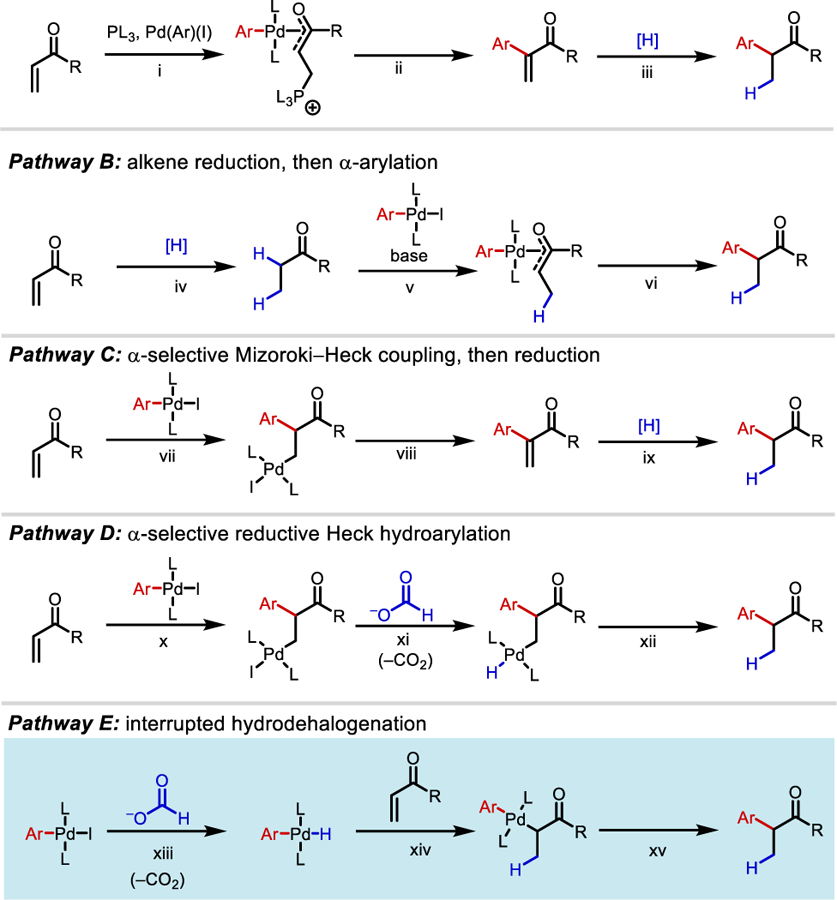

The unusual selectivity of this transformation prompted us to examine the underlying reaction mechanism. We considered four potential pathways (Scheme 1). Pathway A involves a Baylis–Hillman-type mechanism where excess phosphine in solution performs 1,4-addition to access a zwitterion that binds the oxidative addition complex [PdII(Ar)(I)] (step i). Reductive elimination followed by β-phosphine elimination then delivers an α-arylated α,β-unsaturated intermediate (step ii). Reduction of this alkene intermediate furnishes the α-arylated product (step iii). In Pathway B, the alkene is first reduced to the corresponding aliphatic amide (step iv) and then undergoes Buchwald–Hartwig α-arylation to forge the key C(α)–Ar bond via a mechanism of enolate formation, complexation with [PdII(Ar)(I)] (step v), and subsequent reductive elimination (step vi).

Scheme 1.

Possible mechanistic pathways

The third possibility (Pathway C) involves aryl insertion into the α-position of the alkene (step vii), the resulting [PdII(1°-alkyl)(I)] complex β-hydride eliminate (step viii) in a classical Mizoroki–Heck mechanism. The resulting alkene can be reduced to generate the α-arylated product (step ix). Alternatively, in a reductive Heck mechanism (Pathway D), the resulting [PdII(1°-alkyl)(I)] can ligand exchange iodide for formate which can undergo decarboxylation to provide a [PdII(1°-alkyl)(H)] complex (step xi). This can perform reductive elimination to provide the α-arylated product (step xii).

At the outset, Pathways C and D seemed unlikely given that it would involve the opposite regioselectivity in the migratory insertion step than what has been previously reported on Heck-coupling of α,β-unsaturated amides, esters, and ketones. In fact, during Minnaard, de Vries, and Reek’s study of reductive Heck hydroarylation of enones, which uses Hünig’s base as the source of hydride and NHC as choice of ligand, only β-arylated products were observed.11 This suggests formate may be involved in selectivity determination for α-versus β-hydroarylation and could be consistent with Pathway E, but not with C or D. Although α-selectivity has been observed in intramolecular cyclizations, this has not been previously documented in intermolecular systems.12

Next, we considered an interrupted hydrodehalogenation paradigm (Pathway E). In this pathway, the [PdII(Ar)(I)] complex exchanges iodide for formate and undergo decarboxylation to furnish a [PdII(Ar)(H)] complex (step xiii). This high reactive species can insert hydride into the β-position of the alkene (step xiv). The resulting [PdII(Ar)(enolate)] can undergo reductive elimination to provide the α-arylated product (step xv).

In an initial control experiment, we found that reaction proceeds in the presence of elemental mercury, albeit in lower conversion, ruling out the possibility of palladium nanoparticle catalysis, supporting a homogenous process as in Pathways A–E. To probe the feasibility of Pathways A, B, and C, the putative α-arylated acrylamide (6) and reduced amide (7) intermediates were subjected to the reaction conditions, and no reaction took place in either case, establishing that pathways involving Baylis–Hillman-type coupling or Mizoroki–Heck arylation followed by reduction, and reduction followed by Buchwald–Hartwig-type α-arylation are not viable mechanisms in this catalytic system (Scheme 2A). Having quickly ruled out these mechanistic pathways, we set our attention to differentiating between the reductive Heck and interrupted hydrodehalogenation pathways (Pathways D and E).

Scheme 2.

Control experiments

In an effort to disambiguate between Pathways D and E experimentally, we performed the reaction under standard conditions without formate. We found that without the addition of formate, the only observable product is the classical β-Mizoroki–Heck product 10 (Scheme 2B). When independently prepared trans-PdII(Ar)(I)(PAr3)2 complex 8 was subjected to the standard reaction conditions, a 3:1 (α:β) mixture was observed, along with 24% Mizoroki–Heck byproduct, which is typically not detectable under catalytic conditions (Scheme 2C). This result suggests that high concentrations of PdII(Ar)(I) promote traditional Mizoroki–Heck pathways. The data from a competition kinetic isotope effect experiment using equal parts sodium formate and d1-sodium formate (kH/kD = 1.5), is consistent with formate being involved in the product-determining step (Scheme 2D).13 In addition, in the examples shown in Figures 2 and 3, hydrodehalogenated byproducts (Ar–H) are commonly observed in the 1H NMR spectra of crude reaction mixtures. The products likely arise from reductive elimination from a [PdII(Ar)(H)] species, suggesting that this intermediate is generated under the reaction conditions (see Figure S7 for crude NMR of 3q). Collectively, these results are inconsistent with Pathway D.

Having established that the general reactivity paradigm of Pathway E is operative, we next sought to gain insight into the details of the catalytic process through reaction progress kinetic analysis (RPKA).14 Due to the biphasic, heterogeneous reaction system with dioxane as solvent, reaction kinetics were performed in DMF, which gives a homogenous mixture and leads to similar yields and selectivity (see SI). In DMF at 80 °C, the reaction proceeds to completion in four minutes, so the kinetics were performed at 65 °C to extend the reaction time for ease of sampling (Eq. 1).

|

(1) |

In terms of general features, the reaction exhibits a short induction period (~2 min). A same-excess experiment showed that the rate of starting material consumption accelerates over time; addition of product did not influence this rate. Though at first glance, this would appear to signal catalyst activation (Figure 5a), when one tracks formation of 3a-α and byproducts over the course of the reaction, it is evident that reduced byproduct 7 does not start forming until approximately 40% conversion. Since the rate of 3a-α formation does not change over the course of the reaction, the increased production of 7 accounts for the change in rate of starting material consumption (See Figure S10), suggesting that it is a secondary process not directly related to the main catalytic cycle. With this in mind, we focused the remainder of the analysis on the early portion of the reaction, before secondary processes predominate since they are more likely to reflect the intrinsic kinetics.

Figure 5.

(A) Same excess experiment for reaction shown in eq. 1. (B) Different excess experiments of the reaction shown in eq. 1

A series of different-excess experiment were next performed. The order in palladium was determined by measuring initial rates with varying palladium concentrations. A linear fit when plotting the rate of product formation vs palladium concentration showed first order dependence in catalyst. The reaction was also shown to have apparent overall zero-order kinetics although the rate is influenced positively by the concentration of formate and negatively by the concentration of alkene (Figure 5B).

This could be explained by the situation represented in eq. 2, where high concentrations of formate drive the equilibrium to favor formation of the on-cycle palladium-formate complex [a3] and high concentrations of acrylamide favor the formation of the off-cycle palladium-iodo complex [b1], where ligand exchange to generate neither [a3] or [b1] is turnover limiting.15 In addition, zero-order kinetics suggest nothing is coming on to the catalytic cycle during the turnover limiting step which, combined with the KIE data, is evidence for formate decarboxylation being turnover limiting.

|

(2) |

To test this hypothesis, we sought to observe the catalyst resting state using in situ 31P NMR spectroscopy. Monitoring was performed at 162 MHz, in DMF-d7, at 70 °C, using triphenylphosphine sulfide (42.59 ppm) as reference with scans taken every 2 min for 10 min. In order to be able to compare the NMR data with known structures reported in the literature and to avoid issues with aryl group exchange with the oxidative addition complex, we elected to use triphenylphosphine as ligand for this experiment. 6,16

Initial optimization showed that when using triphenylphosphine as ligand under otherwise standard conditions, the reaction provided 62% 1H NMR yield of 3a with 12:1 α:β selectivity, suggesting that the key features of the reactions with PPh3 and P(4-F-C6H4)3 are qualitatively similar (Table S1). Additionally, a separate in situ 19F NMR monitoring experiment with P(4-F-C6H4)3 showed analogous speciation to triphenylphosphine (Figure S13).

With PPh3, major 31P NMR resonances were observed at 27.55 ppm (triphenylphosphine oxide), 22.58 ppm (trans-Pd(Ar)(formate)(PPh3)2), 5.87 (phosphate tribasic), and −4.42 (triphenylphosphine) (Figure 6). The only observable PPh3-bound palladium species was the trans-Pd(Ar)(formate)(PPh3)2 complex. This result suggests this is the predominant catalyst resting state, and based on Alper’s detailed study into the behavior of these complexes, provides support for formate decarboxylation being rate-limiting.6,17

Figure 6.

31P NMR spectrum of reaction in eq 1 after 4 min.

Previous studies have been performed on the behavior of palladium oxidative addition complexes in the presence of acetate. These studies have shown that oxidative addition into aryl-iodide bonds in the presence of acetate favors the [PdII(Ar)(OAc)] complexes.16,18 This reactivity trend can be extended to formate, and we propose that ligand exchange of iodide to formate is also fast. This process is reversible with the equilibrium favoring formation of the [PdII(Ar)(formate)] complex. We believe this equilibrium to be a major driver for the selectivity of this process.

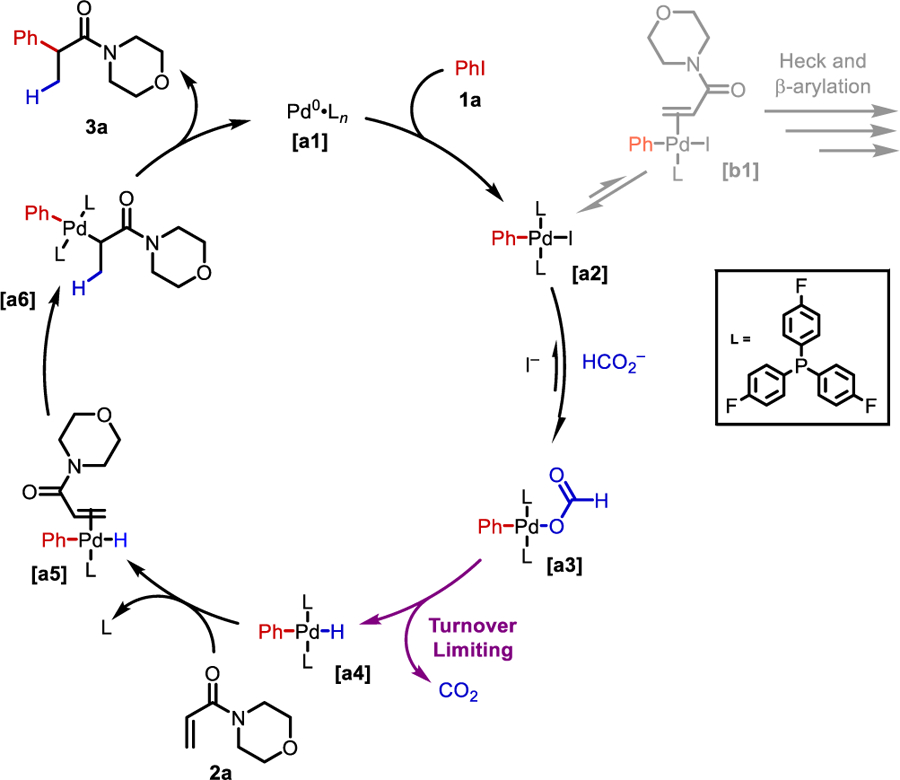

Based on the kinetic data and in situ NMR studies, a mechanism is proposed (Scheme 3). Palladium(0) undergoes oxidative addition into iodobenzene to form a [PdII(Ph)(I)(PAr3)2] complex [a2]. This complex can progress off-cycle by undergoing exchange of a phosphine ligand for an alkene molecule, which leads to Heck and β-arylated byproducts [b1], explaining the decrease in rate at high alkene and low ligand concentrations. Alternatively, complex [a2] can progress on-cycle by undergoing ligand exchange with formate to generate the [PdII(Ar)(formate)] complex [a3]. The formate-complex undergoes irreversible decarboxylation in the turnover limiting step to generate CO2 and [PdII(Ar)(H)] complex [a4]. This complex coordinates alkene to generate [a5] and undergoes migratory insertion into the electronically activated β-position of the alkene to generate an [PdII(Ar)(enolate)] [a6]. This can undergo reductive elimination to furnish the α-arylated product 3a.

Scheme 3.

Proposed catalytic cycle

We believe it is the high ligand loading and rapid exchange of iodide for formate that drives the selectivity for this catalytic cycle. Without the addition of base or water, the reaction suffers from poor selectivity and high amounts of Heck-type products. This is also the case for ligand:Pd ratios of less than 2:1 (see Figure S11).

CONCLUSION.

A novel method for the α-arylation of amides and esters using a mild, palladium-catalyzed hydroarylation has been developed. This chemistry is tolerant of a wide range of substrates including heterocycles and internal α,β-unsaturated acrylamides in high yield and selectivity. The mechanism of this reaction has been evaluated using reaction progress kinetic analysis and in situ reaction monitoring to suggest an unprecedented hydride first pathway made possible by the rapid formation and decomposition of a [PdII(Ar)(formate)] complex.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was financially supported by the National Institutes of Health (5R35GM125052–03 and diversity supplement, 5R35GM125052–03S1), Bristol-Myers Squibb, the Alfred P. Sloan Fellowship Program, and the Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Program. We thank the National Science Foundation (NSF/DGE-1346837) (J.A.G.) for a predoctoral fellowship. Dr. Jason S. Chen (Scripps Research Automated Synthesis Facility) is acknowledged for assistance with HRMS, Drs. Gary J. Balaich and Milan Gembicky (USCD) are acknowledged for assistance with X-Ray crystallography, and Professor Donna G. Blackmond and Dr. David E. Hill are acknowledged for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

(Word Style “TE_Supporting_Information”). Supporting Information. A brief statement in nonsentence format listing the contents of material supplied as Supporting Information should be included, ending with “This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.” For instructions on what should be included in the Supporting Information as well as how to prepare this material for publication, refer to the journal’s Instructions for Authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) For general reviews on transition-metal-catalyzed α-arylation, see: Lloyd-Jones GC, Palladium-Catalyzed α-Arylation of Esters: Ideal New Methodology for Discovery Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2002, 41, 953–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Culkin DA; Hartwig JF Palladium-Catalyzed α-Arylation of Carbonyl Compounds and Nitriles. Acc. Chem. Res 2003, 36, 234–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Johansson CCC; Colacot TJ Metal-Catalyzed α-Arylation of Carbonyl and Related Molecules: Novel Trends in C–C Bond Formation by C–H Bond Functionalization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2010, 49, 676–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Barde E; Guérinot A; Cossy J α-Arylation of Amides from α-Halo Amides Using Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. Synthesis 2019, 51, 178–184. [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Shaughnessy KH; Hamann BC; Hartwig JF Palladium-Catalyzed Inter- and Intramolecular α-Arylation of Amides. Application of Intramolecular Amide Arylation to the Synthesis of Oxindoles. J. Org. Chem 1998, 63, 6546–6553. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kawatsura M; Hartwig JF, Simple, Highly Active Palladium Catalysts for Ketone and Malonate Arylation: Dissecting the Importance of Chelation and Steric Hindrance. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 1473–1478. [Google Scholar]; (c) Fox JM; Huang X; Chieffi A; Buchwald SL Highly Active and Selective Catalysts for the Formation of α-Aryl Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar]; (d) Moradi WA; Buchwald SL Palladium-Catalyzed α-Arylation of Esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 7996–8002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Beare NA; Hartwig JF Palladium-Catalyzed Arylation of Malonates and Cyanoesters Using Sterically Hindered Trialkyl- and Ferrocenyldialkylphosphine Ligands. J. Org. Chem 2002, 67, 541–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Cossy J; de Filippis A; Pardo DG, Palladium-Catalyzed Intermolecular α-Arylation of N-Protected 2-Piperidinones. Org. Lett 2003, 5, 3037–3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Hama T; Liu X; Culkin DA; Hartwig JF Palladium-Catalyzed α-Arylation of Esters and Amides under More Neutral Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 11176–11177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Liu X; Hartwig JF Palladium-Catalyzed Arylation of Trimethylsilyl Enolates of Esters and Imides. High Functional Group Tolerance and Stereoselective Synthesis of α-Aryl Carboxylic Acid Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 5182–5191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Hao Y-J; Hu X-S; Zhou Y; Zhou J; Yu J-S Catalytic Enantioselective α-Arylation of Carbonyl Enolates and Related Compounds. ACS Catal 2020, 10, 955–993 [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Gooßen LJ Pd-Catalyzed Synthesis of Arylacetic Acid Derivatives from Boronic Acids. Chem. Commun 2001, 669–670.; (b) Lundin PM; Esquivias J; Fu GC, Catalytic Asymmetric Cross-Couplings of Racemic α-Bromoketones with Arylzinc Reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 154–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bellina F; Rossi R Transition Metal-Catalyzed Direct Arylation of Substrates with Activated sp3-Hybridized C–H Bonds and Some of Their Synthetic Equivalents with Aryl Halides and Pseudohalides. Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 1082–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Sivanandan ST; Shaji A; Ibnusaud I; Seechurn CCCJ; Colacot TJ, Palladium-Catalyzed α-Arylation Reactions in Total Synthesis. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2015, 38–49.

- (4).(a) For selected reviews on the Heck reaction, see: Beletskaya IP; Cheprakov AV The Heck Reaction as a Sharpening Stone of Palladium Catalysis. Chem. Rev 2000, 100, 3009–3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Felpin F-X; Nassar-Hardy L; Le Callonnec F; Fouquet E Recent Advances in the Heck–Matsuda Reaction in Heterocyclic Chemistry. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 2815–2831. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mc Cartney D; Guiry PJ The Asymmetric Heck and Related Reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 5122–5150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Gurak JA Jr.; Engle KM Practical Intermolecular Hydroarylation of Diverse Alkenes via Reductive Heck Coupling. ACS Catal 2018, 8, 8987–8992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Oxtoby LJ; Gurak JA Jr.; Wisniewski SR; Eastgate MD; Engle KM Palladium-Catalyzed Reductive Heck Coupling of Alkenes. Trends Chem 2019, 1, 572–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Grushin VV; Bensimon C; Alper H The First Isolable Organopalladium Formato Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, and X-ray Structure. Facile and Convenient Thermal Generation of Coordinatively Unsaturated Palladium(0) Species. Organometallics 1995, 14, 3259–3263. [Google Scholar]

- (7).For a review on hydrodehalogenation and related reactions, see: Modak A; Maiti D Metal Catalyzed Defunctionalization Reactions. Org. Biomol. Chem 2016, 14 (1), 21–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Lv H; Xiao L-J; Zhao D; Zhou Q-L Nickel(0)-Catalyzed Linear-Selective Hydroarylation of Unactivated Alkenes and Styrenes with Aryl Boronic Acids. Chem. Sci 2018, 9, 6839–6843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lv H; Kang H; Zhou B; Xue X; Engle KM; Zhao D Nickel-Catalyzed Intermolecular Oxidative Heck Arylation Driven by Transfer Hydrogenation. Nat. Commun 2019, 10, 5025–5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) He Y; Liu C; Yu L; Zhu S, Ligand-Enabled Nickel-Catalyzed Redox-Relay Migratory Hydroarylation of Alkenes with Arylborons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020. 10.1002/anie.202001742. [DOI] [PubMed]

- (9).(a) For reviews, see: Crisenza GEM; Bower JF, Branch Selective Murai-type Alkene Hydroarylation Reactions. Chem. Lett 2016, 45, 2–9. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dong Z; Ren Z; Thompson SJ; Xu Y; Dong G Transition-Metal-Catalyzed C–H Alkylation Using Alkenes. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 9333–9403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) For selected recent examples, see: Crisenza GEM; Sokolova OO; Bower JF Branch-Selective Alkene Hydroarylation by Cooperative Destabilization: Iridium-Catalyzed ortho-Alkylation of Acetanilides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 14866–14870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Xing D; Dong G, Branched-Selective Intermolecular Ketone α-Alkylation with Unactivated Alkenes via an Enamide Directing Strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 13664–13667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Grélaud S; Cooper P; Feron LJ; Bower JF Branch-Selective and Enantioselective Iridium-Catalyzed Alkene Hydroarylation via Anilide-Directed C–H Oxidative Addition. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 9351–9356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zhang M; Hu L; Lang Y; Cao Y; Huang G, Mechanism and Origins of Regio- and Enantioselectivities of Iridium-Catalyzed Hydroarylation of Alkenyl Ethers. J. Org. Chem 2018, 83, 2937–2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Xing D; Qi X; Marchant D; Liu P; Dong G, Branched-Selective Direct α-Alkylation of Cyclic Ketones with Simple Alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 4366–4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Verma P; Richter JM; Chekshin N; Qiao JX; Yu J-Q, Iridium(I)-Catalyzed α-C(sp3)–H Alkylation of Saturated Azacycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 5117–5125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ji Y; Plata RE; Regens CS; Hay M; Schmidt M; Razler T; Qiu Y; Geng P; Hsiao Y; Rosner T; Eastgate MD; Blackmond DG, Mono-Oxidation of Bidentate Bis-phosphines in Catalyst Activation: Kinetic and Mechanistic Studies of a Pd/Xantphos-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 13272–13281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).(a) Raoufmoghaddam S; Mannathan S; Minnaard AJ; de Vries JG; Reek JNH Palladium(0)/NHC-Catalyzed Reductive Heck Reaction of Enones: A Detailed Mechanistic Study. Chem. Eur. J 2015, 21, 18811–18820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Raoufmoghaddam S; Mannathan S; Minnaard AJ; de Vries JG; de Bruin B; Reek JNH, Importance of the Reducing Agent in Direct Reductive Heck Reactions. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 266–272. [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Diethelm S; Carreira EM Total Synthesis of (±)-Gelsemoxonine. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 8500–8503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shen C; Liu R-R; Fan R-J; Li Y-L; Xu T-F; Gao J-R; Jia Y-X Enantioselective Arylative Dearomatization of Indoles via Pd-Catalyzed Intramolecular Reductive Heck Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 4936–4939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kong W; Wang Q; Zhu J Water as a Hydride Source in Palladium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Reductive Heck Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 3987–3991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Simmons EM; Hartwig JF On the Interpretation of Deuterium Kinetic Isotope Effects in C–H Bond Functionalizations by Transition-Metal Complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 3066–3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Blackmond DG, Reaction Progress Kinetic Analysis: A Powerful Methodology for Mechanistic Studies of Complex Catalytic Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2005, 44, 4302–4320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Blackmond DG, Kinetic Profiling of Catalytic Organic Reactions as a Mechanistic Tool. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 10852–10866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Burés J, A Simple Graphical Method to Determine the Order in Catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 2028–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).(a) Rosner T; Pfaltz A; Blackmond DG Observation of Unusual Kinetics in Heck Reactions of Aryl Halides: The Role of Non-Steady-State Catalyst Concentration. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 4621–4622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Blackmond DG; Schultz T; Mathew JS; Loew C; Rosner T; Pfaltz A Comprehensive Kinetic Screening of Palladium Catalysts for Heck Reactions. Synlett 2006, 3135–3139. [Google Scholar]

- (17).(a) Grushin VV; Alper H, The Existence and Stability of Mononuclear and Binuclear Organopalladium Hydroxo Complexes, [(R3P)2Pd(R’)(OH)] and [(R3P)2Pd2(R’)2(μ-OH)2]. Organometallics 1996, 15, 5242–5245. [Google Scholar]; (b) Amatore C; Carre E; Jutand A; M’Barki MA; Meyer G Evidence for the Ligation of Palladium(0) Complexes by Acetate Ions: Consequences on the Mechanism of Their Oxidative Addition with Phenyl Iodide and PhPd(OAc)(PPh3)2 as Intermediate in the Heck Reaction. Organometallics 1995, 14, 5605–5614. [Google Scholar]; (c) Molloy JJ; Seath CP; West MJ; McLaughlin C; Fazakerley NJ; Kennedy AR; Nelson DJ; Watson AJB Interrogating Pd(II) Anion Metathesis Using a Bifunctional Chemical Probe: A Transmetalation Switch. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18). Based on Eq. 2, the resting state is likely partitioned between a3, a2, and b1. Given that only a3 is identifiable by 31P NMR and that 3a-β is formed in trace amounts, a2 and b1 appear to be minor components.

- (19).Kalek M; Stawinski J Palladium-Catalyzed C–P Bond Formation: Mechanistic Studies on the Ligand Substitution and the Reductive Elimination. An Intramolecular Catalysis by the Acetate Group in PdII Complexes. Organometallics 2008, 27, 5876–5888. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.