Abstract

Cardiac tumors (CTs) are extremely rare, with an incidence of approximately 0.02% in autopsy series. Primary tumors of the heart are far less common than metastatic tumors. CTs usually present with any possible clinical combination of heart failure, arrhythmias, or embolism. Echocardiography remains the first diagnostic approach when suspecting a CT which, on the other side, frequently appears unexpectedly during an echocardiographic examination. Yet, cardiac tomography and especially magnetic resonance imaging may offer several adjunctive opportunities in the diagnosis of CTs. Early and exact diagnosis is crucial for the following therapy and outcome of CTs.

Keywords: Atrial myxomas, cancer of the heart, cardiac tumors, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of primary cardiac malignancies, echocardiography in the diagnosis of cardiac tumors, malignant tumors of the heart

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac tumors (CTs) are exceedingly rare. With an incidence of approximately 0.02% in autopsy series, primary tumors of the heart are far less common than metastatic tumors. Myxoma is the most common benign tumor (50%–70%); angiosarcoma is the most common malignant one (30%), followed by rhabdomyosarcoma (20%).[1,2] About 10% of all tumor patients develop cardiac metastases, but these are only rarely clinically manifest.[3] Nonetheless, they may cause a wide variety of clinical signs and symptoms that often masquerade as many other more common cardiovascular and systemic diseases. Echocardiography remains the first diagnostic approach when suspecting a CT which, on the other side, frequently appears unexpectedly during an echocardiographic examination. Yet, computed tomography (CT) and especially magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offer several adjunctive advantages that make these technologies the most sophisticated among the imaging techniques available today. An early and correct diagnosis may change the patient's clinical management and prognosis.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

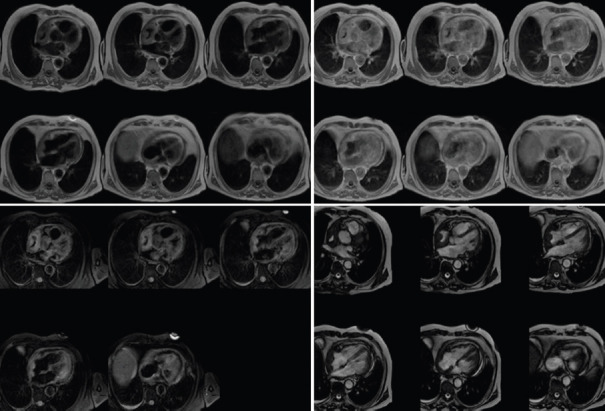

CTs usually present with some combination of heart failure, arrhythmias, or embolic phenomena. Intracavitary tumors are more likely to cause heart failure or embolic phenomena, whereas intramural tumors are more likely to cause arrhythmias. Nevertheless, also intracavitary tumors may have some point of attachment at the cardiac walls and thus can be arrhythmogenic; on the other hand, intramural tumors, if large enough, may bulge and partially obliterate a cardiac chamber or interfere with a ventricle's mechanical performance and thus cause heart failure. Therefore, the specific signs and symptoms produced by tumors are more closely related to their precise anatomical location, size, and relationships with the surrounding structures than to their histological type. Tumors localized in the region of the atria or atrioventricular valves may restrict the blood flow into the heart, mimicking stenosis of the mitral or tricuspid valve. Mobile, pedunculated neoplasms generally lead to paroxysmal heart failure, syncope, dyspnea, or embolism. Tumor infiltration into the ventricular walls may produce symptoms similar to hypertrophic or restrictive cardiomyopathy; the clinical presentation is dominated by heart failure.[4] At ECG, pseudoischemic changes may be evident in the corresponding leads [Figure 1].[5] Expansion into the superior vena cava (SVC) may result in SVC syndrome. Tumor infiltration of the neural pathways or of the conduction system can cause irregular heartbeat and especially atrioventricular block (this is particularly common for fibromas); in some cases, the first manifestation of a CT is sudden cardiac death. CTs are often diagnosed after the patient has suffered a stroke, an embolism of the peripheral vasculature, or a pulmonary artery embolism, caused by detached tumor tissue or mobilization of thrombotic deposits. The possibility of paradoxical embolisms should also be kept in mind. Therefore, all fragments of embolic material retrieved during diagnostic investigations should be subjected to histological analysis. In particular, myxomas tend to cause embolisms because of their gelatinous structure.[6,7,8,9] Papillary fibroleastomas also have systemic embolism as the most common nical presentation.[7,8]

Figure 1.

Metastatic angiosarcoma infiltrating the right ventricular wall. Top: 2D-echo long axis view. Down: pseudoischemic anomalies on corresponding leads

CLASSIFICATION

CTs are divided into benign, malignant, and intermediate tumors of uncertain behavior, with separate sections on germ cell tumors and tumors of the pericardium [Tables 1 and 2].[10]

Table 1.

WHO Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart6

| Benign Tumors and Tumor-Like Conditions |

| Rhabdomyoma |

| Histiocytoid cardiomyopathy |

| Hamartoma of mature cardiac myocytes |

| Adult cellular rhabdomyoma |

| Cardiac myxoma |

| Papillary fibroelastoma |

| Hemangioma, NOS |

| Capillary hemangioma |

| Cavernous hemangioma |

| Arteriovenous malformation |

| Intramuscular hemangioma |

| Cardiac Fibroma |

| Lipoma |

| Cystic tumor of the atrioventricular node |

| Granular cell tumor |

| Schwannoma |

| Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor |

| Paraganglioma |

| Germ cell tumors |

| Teratoma, mature |

| Teratoma, immature |

| Yolk sac tumor |

| Malignant tumors |

| Angiosarcoma |

| Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma |

| Osteosarcoma |

| Myxofibrosarcoma |

| Leiomyosarcoma |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Synovial sarcoma |

| Miscellaneous sarcomas |

| Cardiac lymphomas |

| Metastatic tumors |

| Tumors of the pericardium |

| Solitary fibrous tumor |

| Malignant |

| Angiosarcoma |

| Synovial sarcoma |

| Malignant mesothelioma |

| Germ cell tumors |

| Teratoma, mature |

| Teratoma, immature |

| Yolk sac tumor |

Table 2.

Clinicopathologic Features of Primary Heart Tumors

| Histologic Type | Age | Site in Heart | Multiplicity | Syndromic Association | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fetuses, Iinfants | Children | Adults | Layer | Location | |||

| Benign congenital tumors | |||||||

| Rhabdomyoma | ++ | + | Myocardium | Ventricles | Usual | Tuberous sclerosis | |

| Fibroma | + | ++ | + | Myocardium | Ventricle, ventricular septum | Rare | Gorlin syndrome |

| Histiocytoid cardiomyopathy | ++ | +/1 | Endocardium, myocardium | Ventricles, atrial, AV SA nodes | Always | ||

| Benign acquired tumors | |||||||

| Myxoma | +/- | ++ | Endocardium | LA, atrial septum | Rare | Carney complex | |

| RA, atrial septum | |||||||

| Papillary fibroelastoma | ++ | Endocardium | Valves >atria >ventricles | Occasional | |||

| Hemangiomab | + | + | + | Myocardium Endocardium | Atria >ventricles | Unusual | |

| Lipomatous hypertrophy | ++ | Myocardium of atrial septum | |||||

| Lipoma | ++ | Myocardium, epicardium, endocardium | All sites | Rare | |||

| Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumord | ++ | + | +/- | Endocardium | Valves >atria | Occasional | |

| Germ cell tumors | |||||||

| Teratoma | ++ | + | +/- | Pericardial cavity | No | ||

| Ventricular septum (rare) | |||||||

| Yolk sac tumor | ++ | + | Pericardial cavity | No | |||

| Ventricular septum (rare) | |||||||

| Malignant tumors | |||||||

| Angiosarcoma | +/- | ++ | All layers | Right atrium, pericardium | Occasional | ||

| UPS/myxofibrosarcoma | +/- | +/- | ++ | Endocardium | Left atrium | Rare | |

| Other sites | |||||||

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | +/- | ++ | + | Myocardium | Ventricles | No | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | +/- | ++ | Endocardium | Left atrium | No | ||

| Lymphoma | +/- | ++ | Myocardium | Right atrium, others | Occasional | ||

WHO, World Health Organization; AV, atrioventricular; SA, sinoatrial; LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium; UPS, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma.

Most primary CTs are benign in nature. Of these benign CTs, cardiac myxomas by far are the most common entities in adults and rhabdomyomas in the pediatric population.

Cardiac myxoma

Cardiac myxoma typically presenting between the ages of 30 and 60 years and more commonly in women.[7,8,9] Approximately, 75% of myxomas occur in the left atrium where the site of attachment is almost always in the region of the limbus of the fossa ovalis. Myxomas may occasionally be found on the posterior left atrial wall, but tumors presenting in this location should raise the suspicion of malignancy; typically intracavitary, solitary mobile, and pedunculated, myxomas may prolapse to various degrees into the mitral valve orifice, resulting in obstruction of blood flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle as well as mitral regurgitation. Embolic events occur in 30% of patients. Myxomas also may occur in the right atrium (15%–20%). Carney complex is an autosomal dominant pattern syndrome, in which atrial and noncardiac myxomas, schwannomas, and various endocrine tumors are present, along with various skin pigmentation abnormalities.[11]

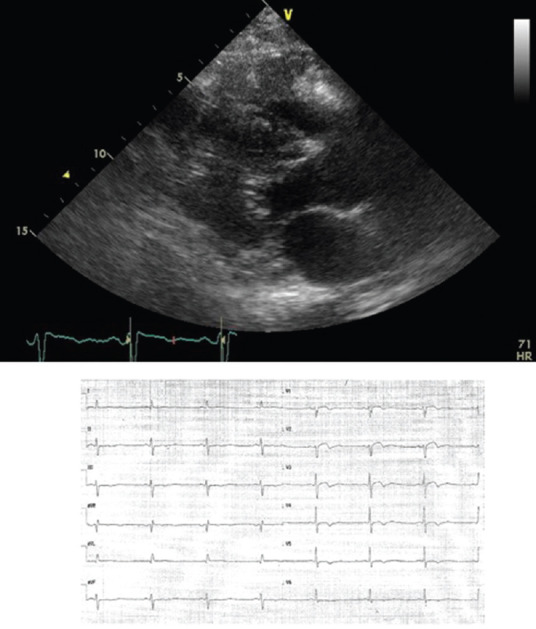

Papillary fibroelastoma [Figure 2]

Figure 2.

Papillary Fibroelastoma, 67-year old patient after transient ischemic attack (30 days earlier). 2D (left) and 3D (right) transthoracic echocardiogram showing a round formation with soft consistence on the atrial side of septal leaflet of tricuspid valve, firstly and erroneously considered ad an endocardial vegetation

Papillary fibroelastoma (PFE) is the most common tumor of the cardiac valves; it is a benign papilloma of the endocardium with a highly mobile stalk and is more often singular than multiple [Figure 2]. PFEs are most commonly localized on the valves, primarily the aortic valve followed by the mitral valve, mainly in the downstream side, with dimensions between 2 and 40 mm. Larger PFEs are seen when they occur on the right-sided valves, and they have the potential to embolize to vital structures. Embolization may occur from the fragile papillary fronds of the mass itself or from thrombotic material formed on the tumor. Accordingly to recent guidelines, intravenous alteplase is not contraindicated and may be reasonable for patients with major acute ischemic stroke likely to produce severe disability and cardiac myxoma or PFE.[12] These tumors may mimic infective endocarditis.

Lipomatous hypertrophy and lipomas

Lipomatous hypertrophy (LHAS) and lipomas arise from benign neoplastic proliferation of nature adipocytes. True lipomas are rare and can occur at any age and with equal frequency in both sexes. They range in diameter from 1 to 15 cm. Most tumors are sessile or polypoid and occur in the subendocardium or subepicardium and are usually enclosed in a capsule. LHIS classically involves the anterior or superior portion of the interatrial septum and spares the fossa ovalis. On average, the septum is thickened up to 2.5 cm. Clinically, LHIS is associated with a higher incidence of atrial arrhythmias, that is, correlated with the degree of hypertrophy. Massive lipomatous hypertrophy can cause obstruction of the SVC.

Rhabdomyomas

Rhabdomyomas are the most common CTs of children and infants. Evidence suggests that rhabdomyomas correspond to a focal hamartomatous accumulation of the striated cardiomyocytes, and it is not actually a neoplasm. Rhabdomyomas occur most frequently in the myocardium of the left ventricle or in the interventricular septum, and they are strongly associated with tuberous sclerosis and appear usually as small and lobulated intramural nodules, with diameters in the range of 2 mm to 2 cm. Typically, rhabdomyomas tend to regress spontaneously, and this occurs in 50% of patients.[13,14]

Fibromas

Fibromas are benign connective tissue tumors derived from fibroblast that occurs predominantly in children and constitute the second most frequent type of primary CT occurring in the pediatric age group. Typically are large tumors ranging from 3 to 10 cm in diameter. They usually occur within the ventricular myocardium and much more frequently within the anterior free wall of the left ventricle or the interventricular septum than in the posterior let ventricular wall or right ventricle. Approximately 70% of fibromas are symptomatic, causing mechanical interference with intracardiac flow, ventricular systolic function, or conduction disturbances.

Hemangiomas

Hemangiomas are extremely rare accounting for 5%–10% of benign tumors. They may occur in any part of the heart but more commonly are found in the lateral wall of the left ventricle, the anterior wall of the right ventricle, or the interventricular septum. Most often, they are incidentally, detected during examinations done for other reasons.

Teratomas

Teratomas are generally observed in children and occur in the pericardium. They are often attached to the base of the great vessels (root of the aorta or the pulmonary trunk). About 90% are located in the anterior mediastinum; the rest, mainly in the posterior mediastinum.[15]

Malignant primary tumors include sarcomas, pericardial mesothelioma, and primary lymphomas

Sarcoma

Sarcoma is a rare type of cancer that occurs in adults, children, and teens. Sarcomas may occur at any age but are most common between the third and fifth decade. Almost 40% are angiosarcomas, have a striking predilection for the right atrium/right ventricle and pericardium, causing right ventricular inflow tract obstruction, pericardial tamponade, and lung metastasis. Other types include undifferentiated sarcoma (25%), malignant fibrous histiocytoma (11%–24%), leiomyosarcoma (8%–9%), fibrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, and osteosarcoma; these types are more likely to originate in the left atrium, causing mitral valve obstruction and heart failure.

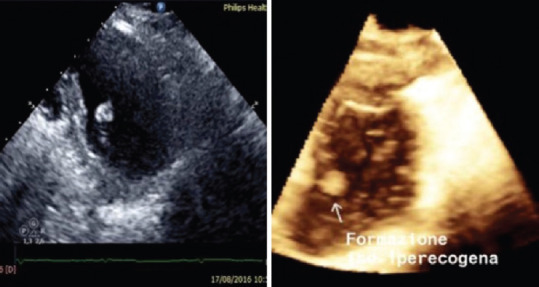

Primary lymphoma

Primary lymphoma is extremely rare. It occurs more frequently in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or other people with immunodeficiency. These tumors may infiltrate the cardiac walls and grow within the atrial and/or ventricular cavities; they usually grow rapidly and may cause heart failure, arrhythmias, tamponade, and superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome [Figure 3].[16,17,18,19]

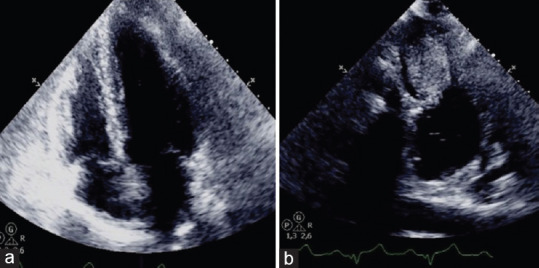

Figure 3.

(a) 2D apical 3-chamber view; (b) 2D apical 4-chamber view. Pericardial effusion and infiltrative mass on left and right ventricular apex, suggestive for malignancy in hip liposarcoma, endometrial adenocarcinoma, and breast infiltrating carcinoma. Final diagnosis was lymphoma

Metastatic tumors

Metastases can reach the heart via the lymphatic way or through the arterial or venous circulation. Lymphatic spread is common for lung and breast cancers and for some sarcomas and lymphomas; it frequently causes pericardial effusion and may cause the so-called “tumor encasement of the heart,” with constriction pattern.[20,21,22] It is important to bear in mind the possibility of a tumor encasement (with or without effusion) in the patients presenting with suspected cardiac tamponade because pericardial drainage will be not effective to relieve symptoms. Intracoronary dissemination is common for leukemia, melanoma, and some lymphomas; the metastases are usually intramural, and cases of acute coronary syndrome have been described. Genitourinary tumors often invade the inferior vena cava, grow quickly in a symbiotic way with superimposed thrombus (the so-called “tumor thrombosis) and reach the right atrium.[23,24] Melanoma is a tumor with a high propensity for cardiac involvement; lung and breast carcinoma, soft-tissue sarcoma, and renal cancer are also common sources of metastases to the heart.[25,26] Leukemia and lymphoma often metastasize to the heart. Considering both the prevalence of the primary tumor and the propensity to metastasize, the most common secondary tumor of the heart observed in the clinical practice is lung carcinoma (35%–40%), followed by hematologic malignancies (10%–20%) and breast cancer (10%).[27]

DIAGNOSIS

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is usually the first diagnostic procedure. When a cardiac mass is detected on echocardiography, the differential diagnosis includes thrombi, benignant tumors, and malignant tumors. The following characteristics must be considered: site, implant, involvement of other structures, and echogenicity. A broad-based mass located in an enlarged left atrium in a patient with atrial fibrillation and/or severe mitral stenosis is likely to be a thrombus. Thrombi in the right chambers are usually an extension or embolus from a deep venous thrombosis; usually, they are serpentine-like and highly mobile.[28] The most common benign tumors (myxomas and PFEs) are pedunculated, and the insertion is in the majority of cases on the left side of the interatrial septum (myxomas) or a cardiac valve (fibroelastomas). Malignant tumors are often broad-based and may have multiple sites; the extension of an intracardiac or pericardial mass in a cardiac wall is usually a marker of malignancy. However, also rhabdomyomas and fibromas may grow within a ventricular wall. Echo contrast agents are useful to confirm the presence of an intracardiac mass and to characterize it further by virtue of the extent of contrast enhancement, which is a marker of vascularity and to assess the myocardial infiltration [Figure 4]. Accordingly, malignant and highly vascular tumors demonstrate hyperenhancement with contrast, whereas thrombi do not appear to enhance at all; myxomas tend to be partially enhanced.[29,30,31] Of note, the uptake of the contrast agent by a CT is usually delayed (several minutes after the injection) and persistent; the use of qualitative and quantitative analysis of the reperfusion time has been proven useful in the differential diagnosis.[32,33] Low mechanical index contrast echocardiography is an easy, noninvasive cardiac imaging tool to assess cardiac mass vascularization. The degree of contrast enhancement and time to opacification are highly variable among cardiac masses and correspond to different extent of vascularization.[34]

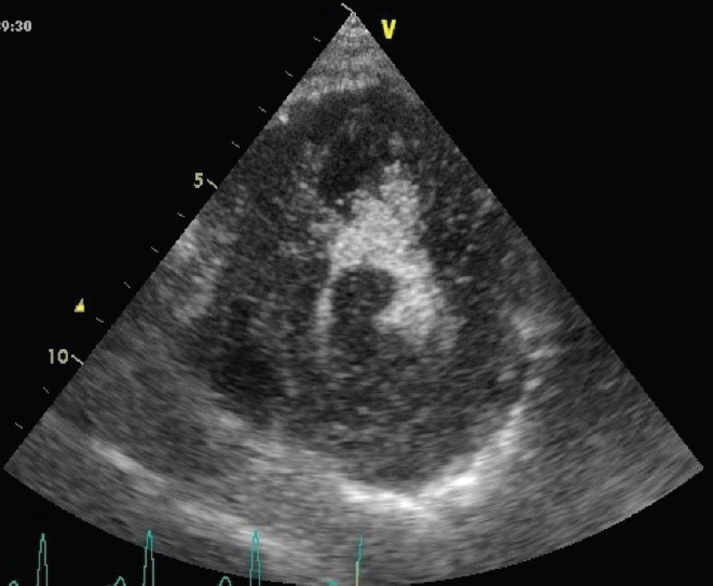

Figure 4.

Echocardiogram of cardiac lymphoma infiltrating the left ventricular wall and protruding into the left ventricular lumen, after contrast injection. The apical septum is partially spared from neoplastic infiltration and appears darker. The small residual left ventricular cavity appears brighter (contrast effect

The identification of tumor thrombosis is of utmost importance in planning the therapies and is better achieved, implementing the echocardiographic examination with sonography.[35]

Transesophageal echocardiography

Transesophageal echocardiography appears to be superior to transthoracic echocardiography when the cardiac mass is located in the atria. The potential advantages of transesophageal echocardiography include improved resolution of the tumor and its attachment, the ability to detect some masses not visualized by transthoracic echocardiography, and to examine the pulmonary veins, venae cavae, the infiltration of the pulmonary veins for the left atrial masses. It should be considered when the transthoracic study is suboptimal, and it is frequently used for intraoperative (transvenous biopsy or cardiac surgery) monitoring [Figures 5 and 6].[36,37,38]

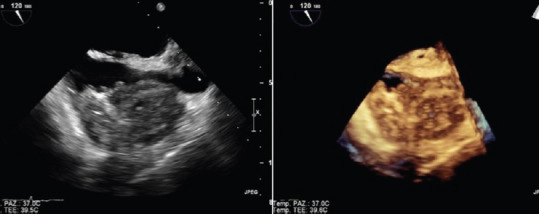

Figure 5.

TEE of right atrial angiosarcoma extendig to superior vena cava. 2D (left) and 3D (right) images (Courtesy of Dr. Rita Piazza)

Figure 6.

Transvenous biopsy of right atrial angiosarcoma (see figure 5). TEE monitoring was used to assess the position of the bioptome (arrow) (Courtesy of Dr. Rita Piazza)

Three-dimensional echocardiography

Three-dimensional (3D) echocardiography, both transthoracic and transesophageal, allows for a more accurate analysis of the mass (site, dimensions) and of its relationship with the neighboring structures. An additional advantage of 3D echo is the possibility of obtaining new section planes on the recorded images, and – using the cropping capability – to identify necrotic areas within the mass.[39,40] If a CT cannot be confirmed by echocardiography, further imaging procedures such as CT or MRI are employed.[41]

Gated cardiac CT can act in a complimentary role to the other modalities in the evaluation of a cardiac mass. CT can provide information, functional assessment, and tissue characterization. With ECG gating to minimize motion-related artifacts, high-speed multistrate equipment provides high-quality images with superior resolution (<1 mm) and the possibility of obtaining multiplanar and tridimensional reconstructions. CT provides a high degree of soft-tissue discrimination, which is helpful in defining the degree of myocardial infiltration. CT can also be used to assess for the presence of calcification, which may be useful in the diagnosis of fibromas, teratomas, rhabdomyomas, hemangiomae, and osteosarcomas. The administration of a contrast agent may clarify further the degree of intramural invasion and can differentiate a vascular tumor from an avascular thrombus. CT provides additional information when the echocardiographic data are equivocal and allows a more accurate evaluation of changes in the follow-up. The main limits of this technique are the use of ionizing radiation.[42]

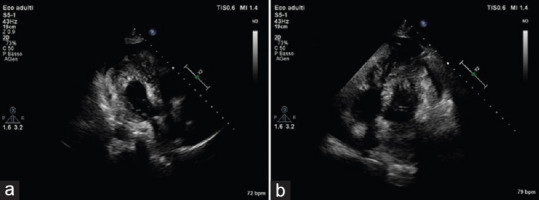

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) will probably become a staple imaging technique for CTs for several reasons, including its excellent spatial and contrast resolution (with no radiation exposure) and its ability to obtain a wide field of view and to perform multiplanar imaging. CMR can identify, with high specificity, cardiac masses that do not require excision: pseudotumors, thrombi, lipomas, lipomatous hypertrophy, and PFEs. Most other CTs will require tissue diagnosis to aid in the establishment of a treatment plan.[43,44,45] T1-weighted and T2-weighted dual-inversion recovery fast spin–echo sequences offer detailed morphological information, with T1-weighted images providing excellent soft-tissue characterization and T2-weighted images providing superior tissue contrast and demonstration of fluid components. For Heterogeneous tumors such as myxomas and teratomas, studies have demonstrated an excellent correlation between MRI and pathological findings. Short inversion recovery sequence permits the suppression of fat signals, and therefore, is useful in detecting lipid-containing masses such as lipoma. Contrast enhancement with gadolinium provides information on the vascularity of the mass; it often allows for better delineation of tumor infiltration within the myocardium and assists in the differentiation of thrombus from tumor. Steady-state free precession sequences cine acquisitions provide excellent 3D visualization of cardiac function, valve motion, and structure, size, attachment to adjacent structures and mobility of cardiac masses. CMR is emerging as the imaging modality of choice for complex cardiac masses [Figures 7-11].[46,47,48]

Figure 7.

cRMI: left, iso-intense in T1-TSE sequences; middle iper-intense in T2; right, PSIR with central hypo-intense core compatible with diagnosis of fibroelastoma (courtesy Dr. Matteo Gravina)

Figure 11.

Angiosarcoma, 68-year old male with history of chest pain and dyspnea. cMRI: Solid tissue with improved contrast enhancement, surrounding the superior vena cava and right atrium and leading to reduced expansion with pericardium thickening and minimal effusion (courtesy of Dr. Matteo Gravina)

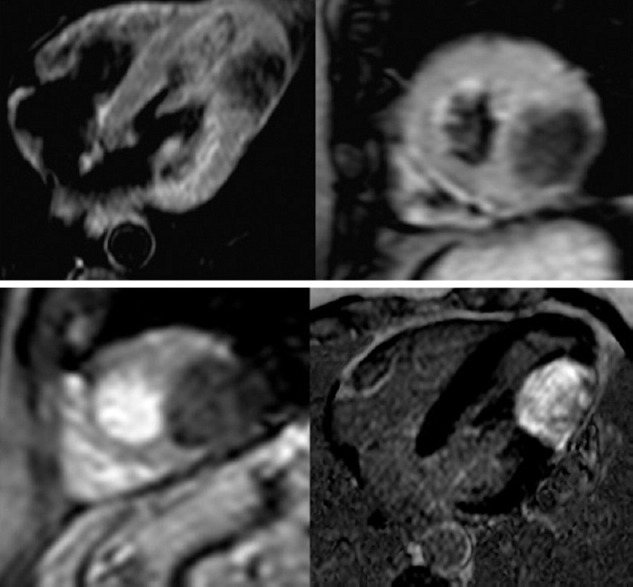

Figure 8.

Lypoma, 60-year old woman, with poor acustic window echocardiogram. Up, cMRI showing rounded capsule formation in right atrium on interatrial septum. Down, hyper-intense in T1 sequence and hypo-intense in fat sat sequences compatible with lypoma (courtesy of Dr. Matteo Gravina)

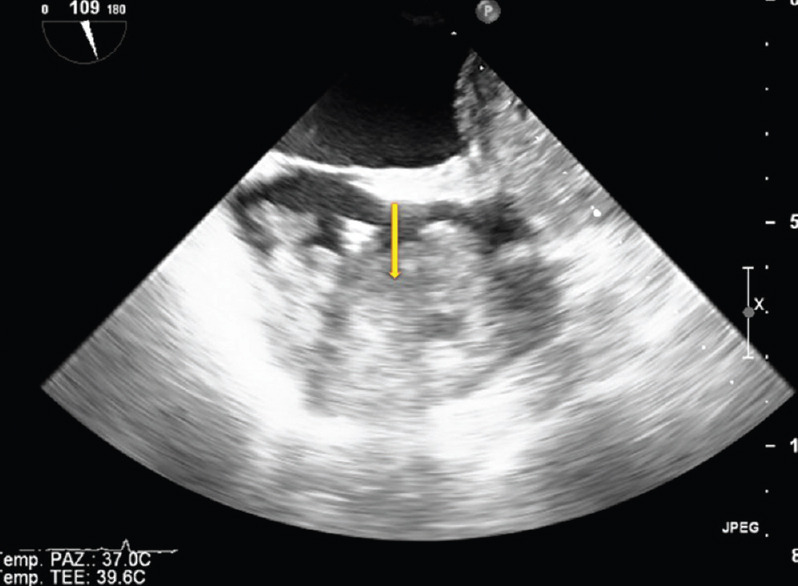

Figure 9.

Cardiac Fibroma, 51-year old man referred for dizziness, sweating and vomit, admitted to acute cardiac care unit with suspected acute coronary syndrome (a) Echocardiography apical 4-chamber view: the mass is not visible. (b) Echocardiography off axis view: oval mass of the left ventricular lateral wall (ref 39,40)

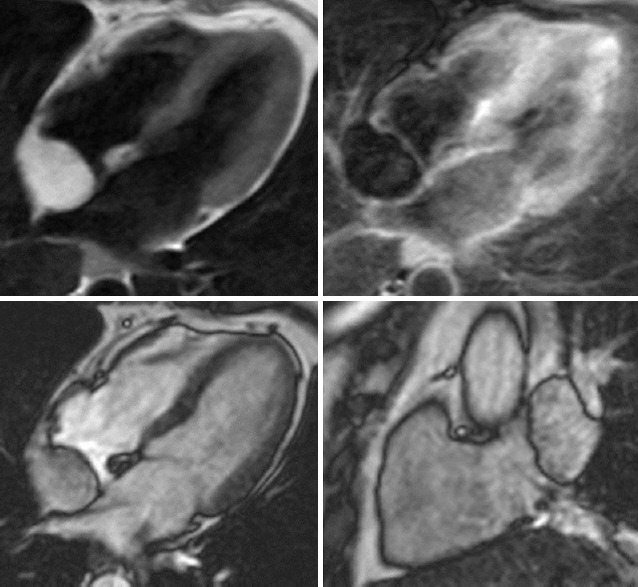

Figure 10.

Cardiac fibroma. Upper, cMRI T2-weighted images 4-chamber and short axis view showing hypo-intense nodular mass in the mid-apical and inferior-lateral wall segments. Down-left, first-pass minimal enhancement with gadolinium. Down-right, late enhancement 4-chamber view, the mass appears as hyper-intense (ref 39,40)

Positron-emission tomography and positron-emission tomography/computed tomography

Positron-emission tomography (PET) and PET/CT give additional information on the metabolic activity of the mass. As tumors are typically in a relatively hypermetabolic state, PET imaging using a metabolic tracer such as 2-fluorine 18 fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (18 FDG) has proven useful in detecting malignant tumors. Glucose metabolism is quantified by the maximum standardized uptake value (SUV). Malignant tumors usually have a high SUV, proportional to their proliferative index; a maximum SUV <3.5 suggests a benign lesion, while a value >10 is highly suggestive of malignancy.[49,50] Using FDG-PET/CT, a sensitivity of over 90% in differentiating benign and malignant processes was achieved.[51] A major problem with18 FDG is the variable uptake by the myocardium, which might reduce the diagnostic accuracy in ventricular tumors.[52] A low-carbohydrate, fat-rich meal followed by a prolonged fasting period reduces the myocardial uptake of glucose and make possible to highlight CTs.[53] The intravenous injection of 50 Units/Kg of body weight of unfractioned heparin shortly before the injection of18 FDG further reduces the physiological myocardial uptake of glucose.[54]

TREATMENT

The treatment of benign primary tumors (myxoma, PFEs, and lipoma) is surgical excision followed by serial echocardiography over 5–6 years to monitor for recurrence.[55] In about 1%–5% of cases, a recurrence or second cardiac myxoma has been reported after resection of the initial one. Rhabdomyomas regress spontaneously after infancy. The prognosis after surgery is usually excellent in the case of benign tumors.

Treatment of malignant primary tumors is surgery, with the goal of a complete resection without infiltrated margins; this is more difficult in large tumors infiltrating the ventricular walls and in angiosarcomas (only in 30% of cases a complete resection is possible).[56] A neoadjuvant (preoperatory) chemotherapy may improve the resectability of large tumors; for left atrial tumors, autotransplantation may be necessary to achieve a complete resection.[57] Chemotherapy and – in selected cases – local radiotherapy may be used after surgery; it is mandatory in all the cases of incomplete resection because the rate of recurrence is usually high and may prolong the time-to-relapse and the overall survival in the other patients.[58,59] An accurate evaluation of the characteristic of malignant tumors (type, size, site, presence of metastases, and rese ctability) before planning any intervention is a mainstay of treatment.[60] Lymphomas are treated by steroids, systemic chemotherapy (and antiretroviral therapy in case of AIDS-related lymphomas).[61,62,63,64]

Treatment of metastatic CTs depends on tumor origin. It is usually based on systemic chemotherapy. For solid tumors, mostly those from lung cancer, with pericardial metastases, intrapericardial chemotherapy increases the rate of complete cure and event-free survival.[65,66] Tumor thrombosis may be treated with an association of chemotherapy and anticoagulants (low molecular weight heparin), but other options (insertion of a vena cava filter, thrombectomy, and closure of the IVC at the time of surgery) may be considered according to the clinical presentation.[67,68]

CONCLUSIONS

Primary CTs are mostly benign and have a good prognosis, whereas malignant primary CTs are most commonly sarcomas and have a poor prognosis. CTs may be misdiagnosed as other conditions (including rheumatic valvular disease, endocarditis, myocarditis, pericarditis, cardiomyopathies, and congenital heart disease), pulmonary conditions (including pulmonary emboli, pulmonary hypertension, and interstitial lung disease), cerebrovascular disease and vasculitis. Advances in noninvasive cardiovascular imaging techniques, especially echocardiography, CT and MRI have greatly facilitated the diagnostic evaluation and permit the rapid identification of intracardiac masses. A multidisciplinary approach is of paramount importance in defining the diagnosis and in planning therapies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Neragi-Miandoab S, Kim J, Vlahakes GJ. Malignant tumours of the heart: A review of tumour type, diagnosis and therapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2007;19:748–56. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rizzo S, Thiene G, Valente M, Basso C. Primary cardiac malignancies: Epidemiology and pathology. In: Lestuzzi C, Oliva S, Ferraù F, editors. Manual of Cardioncology. Springer; 2017. pp. 339–65. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarjeant JM, Butany J, Cusimano RJ. Cancer of the heart: Epidemiology and management of primary tumors and metastases. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2003;3:407–21. doi: 10.2165/00129784-200303060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pino P, Lestuzzi C. Cardiac malignancies. Clinical aspects. In: Lestuzzi C, Oliva S, Ferraù F, editors. Manual of Cardioncology. Springer; 2017. p. 311-. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lestuzzi C, Nicolosi GL, Biasi S, Piotti P, Zanuttini D. Sensitivity and specificity of electrocardiographic ST-T changes as markers of neoplastic myocardial infiltration. Echocardiographic correlation. Chest. 1989;95:980–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.5.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.St John Sutton MG, Mercier LA, Giuliani ER, Lie JT. Atrial myxomas: A review of clinical experience in 40 patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55:371–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinede L, Duhaut P, Loire R. Clinical presentation of left atrial cardiac myxoma. A series of 112 consecutive cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2001;80:159–72. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, Nair GM, Catton C, Yau T, et al. Cardiac tumours: Diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:219–28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoppe UC, La Rosee K, Beuckelmann DJ, Erdmann E. Herztumoren – Manifestation durch uncharakteristische Symptomatik Heart tumors—their manifestation through uncharacteristic symptoms. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1997;122:551–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1047653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A, Nicholson AG, editors . World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. 4th ed. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carney JA, Gordon H, Carpenter PC, Shenoy BV, Go VL. The complex of myxomas, spotty pigmentation, and endocrine overactivity. Medicine (Baltimore) 1985;64:270–83. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198507000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demaerschalk BM, Kleindorfer DO, Adeoye OM, Demchuk AM, Fugate JE, Grotta JC, et al. Scientific rationale for the inclusion and exclusion criteria for intravenous alteplase in acute ischemic stroke: A Statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke. 2016;47:581–641. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain D, Maleszewski JJ, Halushka MK. Benign cardiac tumors and tumorlike conditions. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2010;14:215–30. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Günther T, Schreiber C, Noebauer C, Eicken A, Lange R. Treatment strategies for pediatric patients with primary cardiac and pericardial tumors: A 30-year review. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;29:1071–6. doi: 10.1007/s00246-008-9256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox JN, Friedli B, Mechmeche R, Ismail MB, Oberhaensli I, Faidutti B, et al. Teratoma of the heart. A case report and review of the literature. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1983;402:163–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00695058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chalabreysse L, Berger F, Loire R, Devouassoux G, Cordier JF, Thivolet-Bejui F. Primary cardiac lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: A report of three cases and review of the literature. Virchows Arch. 2002;441:456–61. doi: 10.1007/s00428-002-0711-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuzellier JF, Saade YA, Torossian PF, Baehrel B. Primary cardiac lymphoma: Diagnosis and treatment. Report of 6 cases and review of the literature. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2005;98:875–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nascimento AF, Winters GL, Pinkus GS. Primary cardiac lymphoma: Clinical, histologic, immunophenotypic, and genotypic features of 5 cases of a rare disorder. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1344–50. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3180317341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chin JY, Chung MH, Kim JJ, Lee JH, Kim JH, Maeng IH, et al. Extensive primary cardiac lymphoma diagnosed by percutaneous endomyocardial biopsy. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2009;17:141–4. doi: 10.4250/jcu.2009.17.4.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamura A, Matsubara O, Yoshimura N, Kasuga T, Akagawa S, Aoki N. Cardiac metastasis of lung cancer. A study of metastatic pathways and clinical manifestations. Cancer. 1992;70:437–42. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920715)70:2<437::aid-cncr2820700211>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee DS, Barnard M, Freeman MR, Hutchison SJ, Graham AF, Chiu B. Cardiac encasement by metastatic myxoid liposarcoma. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2002;11:322–5. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(02)00131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ibrahim N, Lopez-Candales A. Cement encasement of the pericardium: Echocardiographic manifestation. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-205276. pii: bcr2014205276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shamberger RC, Ritchey ML, Haase GM, Bergemann TL, Loechelt-Yoshioka T, Breslow NE, et al. Intravascular extension of wilms tumor. Ann Surg. 2001;234:116–21. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200107000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lall A, Pritchard-Jones K, Walker J, Hutton C, Stevens S, Azmy A, et al. Wilms' tumor with intracaval thrombus in the UK children's cancer study group UKW3 trial. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:382–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glancy DL, Roberts WC. The heart in malignant melanoma. A study of 70 autopsy cases. Am J Cardiol. 1968;21:555–71. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(68)90289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klatt EC, Heitz DR. Cardiac metastases. Cancer. 1990;65:1456–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900315)65:6<1456::aid-cncr2820650634>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg AD, Blankstein R, Padera RF. Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation. 2013;128:1790–4. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kronik G. The European cooperative study on the clinical significance of right heart thrombi. Eur Heart J. 1989;12:1046–59. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baumgartner RA, Das SK, Shea M, LeMire MS, Gross BH. The role of echocardiography and CT in the diagnosis of cardiac tumors. Int J Card Imaging. 1988;3:57–60. doi: 10.1007/BF01801645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mansencal N, Revault-d’Allonnes L, Pelage JP, Farcot JC, Lacombe P, Dubourg O. Usefulness of contrast echocardiography for assessment of intracardiac masses. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;102:177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirkpatrick JN, Wong T, Bednarz JE, Spencer KT, Sugeng L, Ward RP, et al. Differential diagnosis of cardiac masses using contrast echocardiographic perfusion imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1412–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lestuzzi C. Primary tumors of the heart. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2016;31:593–8. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uenishi EK, Caldas MA, Tsutsui JM, Abduch MC, Sbano JC, Kalil Filho R, et al. Evaluation of cardiac masses by real-time perfusion imaging echocardiography. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2015;13:23. doi: 10.1186/s12947-015-0018-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barchitta A, Basso C, Piovesana PG, Antonini-Canterin F, Ruzza L, Bianchi A, et al. Opacification patterns of cardiac masses using low-mechanical index contrast echocardiography: Comparison with histopathological findings. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2017;30:72–7. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J, Cheng Y, Lee YZ, Wang Y, Zheng Y, Dong R, et al. Sonography and transthoracic echocardiography for diagnosis of systemic cardiovascular metastatic tumor thrombi. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:1993–2027. doi: 10.7863/ultra.15.10038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters PJ, Reinhardt S. The echocardiographic evaluation of intracardiac masses: A review. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19:230–40. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takaya T, Takeuchi Y, Nakajima H, Nishiki-Kosaka S, Hata K, Kijima Y, et al. Usefulness of transesophageal echocardiographic observation during chemotherapy for cardiac metastasis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma complicated with left ventricular diastolic collapse. J Cardiol. 2009;53:447–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jurkovich D, de Marchena E, Bilsker M, Fierro-Renoy C, Temple D, Garcia H, et al. Primary cardiac lymphoma diagnosed by percutaneous intracardiac biopsy with combined fluoroscopic and transesophageal echocardiographic imaging. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2000;50:226–33. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-726x(200006)50:2<226::aid-ccd19>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaragoza-Macias E, Chen MA, Gill EA. Real time three-dimensional echocardiography evaluation of intracardiac masses. Echocardiography. 2012;29:207–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2011.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plana JC. Three-dimensional echocardiography in the assessment of cardiac tumors: The added value of the extra dimension. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2010;6:12–9. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-6-3-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baumgartner RA, Das SK, Shea M, LeMire MS, Gross BH. The role of echocardiography and CT in the diagnosis of cardiac tumors. Int J Card Imaging. 1988;3:57–60. doi: 10.1007/BF01801645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lestuzzi C, De Paoli A, Baresic T, Miolo G, Buonadonna A. Malignant cardiac tumors: Diagnosis and treatment. Future Cardiol. 2015;11:485–500. doi: 10.2217/fca.15.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoey ET, Mankad K, Puppala S, Gopalan D, Sivananthan MU. MRI and CT appearances of cardiac tumours in adults. Clin Radiol. 2009;64:1214–30. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilkeson RC, Chiles C. MR evaluation of cardiac and pericardial malignancy. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2003;11:173–86, 8. doi: 10.1016/s1064-9689(02)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gravina M, Casavecchia G, Totaro A, Ieva R, Macarini L, Di Biase M, et al. Left ventricular fibroma: What cardiac magnetic resonance imaging may add? Int J Cardiol. 2014;176:e63–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gowda RM, Khan IA, Nair CK, Mehta NJ, Vasavada BC, Sacchi TJ, et al. Cardiac papillary fibroelastoma: A comprehensive analysis of 725 cases. Am Heart J. 2003;146:404–10. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Araoz PA, Eklund HE, Welch TJ, Breen JF. CT and MR imaging of primary cardiac malignancies. Radiographics. 1999;19:1421–34. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.6.g99no031421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grebenc ML, Rosado de Christenson ML, Burke AP, Green CE, Galvin JR. Primary cardiac and pericardial neoplasms: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000;20:1073–103. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.4.g00jl081073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rahbar K, Seifarth H, Schäfers M, Stegger L, Hoffmeier A, Spieker T, et al. Differentiation of malignant and benign cardiac tumors using 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:856–63. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.095364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kikuchi Y, Oyama-Manabe N, Manabe O, Naya M, Ito YM, Hatanaka KC, et al. Imaging characteristics of cardiac dominant diffuse large B-cell lymphoma demonstrated with MDCT and PET/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:1337–44. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2436-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maurer AH, Burshteyn M, Adler LP, Steiner RM. How to differentiate benign versus malignant cardiac and paracardiac 18F FDG uptake at oncologic PET/CT. Radiographics. 2011;31:1287–305. doi: 10.1148/rg.315115003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maurer AH, Burshteyn M, Adler LP, Gaughan JP, Steiner RM. Variable cardiac 18FDG patterns seen in oncologic positron emission tomography computed tomography: Importance for differentiating normal physiology from cardiac and paracardiac disease. J Thorac Imaging. 2012;27:263–8. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e3182176675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kobayashi Y, Kumita S, Fukushima Y, Ishihara K, Suda M, Sakurai M, et al. Significant suppression of myocardial (18) F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake using 24-h carbohydrate restriction and a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet. J Cardiol. 2013;62:314–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Masuda A, Naya M, Manabe O, Magota K, Yoshinaga K, Tsutsui H, et al. Administration of unfractionated heparin with prolonged fasting could reduce physiological 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the heart. Acta Radiol. 2016;57:661–8. doi: 10.1177/0284185115600916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang JG, Wang B, Hu Y, Liu JH, Liu B, Liu H, et al. Clinicopathologic features and outcomes of primary cardiac tumors: A 16-year-experience with 212 patients at a chinese medical center. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2018;33:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vaporciyan A, Reardon MJ. Right heart sarcomas. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2010;6:44–8. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-6-3-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blackmon SH, Patel AR, Bruckner BA, Beyer EA, Rice DC, Vaporciyan AA, et al. Cardiac autotransplantation for malignant or complex primary left-heart tumors. Tex Heart Inst J. 2008;35:296–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leja MJ, Shah DJ, Reardon MJ. Primary cardiac tumors. Tex Heart Inst J. 2011;38:261–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Isambert N, Ray-Coquard I, Italiano A, Rios M, Kerbrat P, Gauthier M, et al. Primary cardiac sarcomas: A retrospective study of the french sarcoma group. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:128–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Paoli A, Miolo GM, Buonadonna A. Cardiac tumors: multimodality approach, follow-up, prognosis. In: Lestuzzi C, Oliva S, Ferraù F, editors. Manual of Cardioncology. Springer; 2017. pp. 417–22. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Soon G, Ow GW, Chan HL, Ng SB, Wang S. Primary cardiac diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: Clinical, histologic, immunophenotypic, and genotypic features of 3 cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2016;24:40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lestuzzi C, Spina M, Martellotta F, Carbone A. Massive myocardial infiltration by HIV-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Echocardiographic aspects at diagnosis and at follow-up. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2012;13:836–8. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3283511fa7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen CF, Hsieh PP, Lin SJ. Primary cardiac lymphoma with unusual presentation: A report of two cases. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6:311–4. doi: 10.3892/mco.2017.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mauricio R, Mgbako O, Buntaine A, Moreira A, Jung A. Complete resolution of tumor burden of primary cardiac non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Case Rep Cardiol. 2016;2016:2124975. doi: 10.1155/2016/2124975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lestuzzi C. Neoplastic pericardial disease: Old and current strategies for diagnosis and management. World J Cardiol. 2010;2:270–9. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v2.i9.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lestuzzi C, Bearz A, Lafaras C, Gralec R, Cervesato E, Tomkowski W, et al. Neoplastic pericardial disease in lung cancer: Impact on outcomes of different treatment strategies. A multicenter study. Lung Cancer. 2011;72:340–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cristofani LM, Duarte RJ, Almeida MT, Odone Filho V, Maksoud JG, Srougi M, et al. Intracaval and intracardiac extension of wilms' tumor. The influence of preoperative chemotherapy on surgical morbidity. Int Braz J Urol. 2007;33:683–9. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382007000500010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ayyathurai R, Garcia-Roig M, Gorin MA, González J, Manoharan M, Kava BR, et al. Bland thrombus association with tumour thrombus in renal cell carcinoma: Analysis of surgical significance and role of inferior vena caval interruption. BJU Int. 2012;110:E449–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]