Abstract

Hospital accreditation has been transferred from high-income countries (HICs) to many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), supported by a variety of advocates and donor agencies. This review uses a policy transfer theoretical framework to present a structured analysis of the development of hospital accreditation in LMICs. The framework is used to identify how governments in LMICs adopted accreditation from other settings and what mechanisms facilitated and hindered the transfer of accreditation. The review examines the interaction between national and international actors, and how international organizations influenced accreditation policy transfer. Relevant literature was found by searching databases and selected websites; 78 articles were included in the analysis process. The review concludes that accreditation is increasingly used as a tool to improve the quality of healthcare in LMICs. Many countries have established national hospital accreditation programmes and adapted them to fit their national contexts. However, the implementation and sustainability of these programmes are major challenges if resources are scarce. International actors have a substantial influence on the development of accreditation in LMICs, as sources of expertise and pump-priming funding. There is a need to provide a roadmap for the successful development and implementation of accreditation programmes in low-resource settings. Analysing accreditation policy processes could provide contextually sensitive lessons for LMICs seeking to develop and sustain their national accreditation programmes and for international organizations to exploit their role in supporting the development of accreditation in LMICs.

Keywords: Hospital accreditation, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), policy transfer, lesson drawing, policy learning

Key Messages

Hospital accreditation has been adopted and developed in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and national accreditation programmes have developed in many of these countries.

Policy transfer theory is a useful tool to analyse policy processes and the transfer of policies from one country or setting to another, including the transfer of accreditation policy to LMICs.

Lack of resources has remained a major challenge to the development of accreditation policy and its sustainability in LMICs.

Analysing accreditation policy processes can provide contextually sensitive lessons for LMICs and for international organizations which support accreditation development in LMICs.

Introduction

Accreditation can be defined as ‘a public recognition by a healthcare accreditation body of the achievement of accreditation standards by a healthcare organisation, demonstrated through an independent external peer assessment of that organisation’s level of performance in relation to the standards’ (Shaw, 2004, p. 9). Accreditation first developed many decades ago in the USA and was adopted in some other Anglophone countries (such as Australia and Canada) before it spread worldwide in the 1990s (Shaw, 2000, 2003). While accreditation originated largely in high-income countries (HICs) (Shaw, 2015), national accreditation programmes have more recently been developed in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Lane et al., 2014).

This literature review provides a structured analysis of the development of hospital accreditation in LMICs. Key questions addressed by the review are to what extent are the structures and processes of hospital accreditation drawn from international models perceived as successful, and to what extent are they shaped by national policy contexts in LMICs? A policy transfer framework (Dolowitz and Marsh, 2000) is used to analyse accreditation policy development and to answer these questions. Policy transfer is defined by Dolowitz and Marsh (1996, p. 344) as ‘a process in which knowledge about policies, administrative arrangements, institutions, etc. in one time and/or place is used in the development of policies, administrative arrangements, and institutions in another time and/or place’.

This growth of accreditation programmes and their implementation in LMICs has been supported by many international organizations. These include, but are not limited to, the International Society for Quality in Healthcare (ISQua), the World Health Organization (WHO), the US-based Joint Commission on Accreditation in Healthcare Organisations (JCAHO), and its international organization: the Joint Commission International (JCI) and donor agencies such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the World Bank (Shaw et al., 2010; Braithwaite et al., 2012). However, the lack of resources in LMICs has remained a major challenge to the transfer of accreditation and its sustainability in these countries (Purvis et al., 2010; Shaw et al., 2010; Mate et al., 2014).

The review also explores who is involved in the transfer of accreditation to LMICs. It examines the interaction between different networks and communication channels involved in the process of accreditation transfer, highlighting the role of international actors in the transfer process. It shows how a policy or practice that is successful in one setting can be transferred to another, and what mechanisms facilitate or hinder the transfer of accreditation policy to LMICs and affect its outcomes. Finally, the review provides contextually sensitive lessons for LMICs seeking to implement and sustain their national accreditation programmes, and for international actors to help them support these countries.

Background

Accreditation programmes can be described in terms of four components: the accreditation body, standards, the survey process and surveyors, and finally incentives (WHO, 2003; Morena-Serra, 2012; Johnson et al., 2016). According to Shaw (2003), the aim of accreditation in HICs is to standardize the processes in healthcare organizations in order to promote safety and quality of care which will result in patient satisfaction, public accountability and staff development. LMICs commonly have limited resources and poor hospital infrastructure, so their main focus is often to ensure better and equal access to healthcare services by establishing basic health facilities with adequate staffing and equipment (Shaw, 2003). However, LMICs can still vary widely with regard to their actual level of resources, along with other factors such as, political goals, the existing healthcare infrastructure, involvement in conflicts and population demographics, all of which may influence the nature of their national accreditation programmes. For example, in 2018 the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in Lebanon was almost 70% higher than that in nearby Egypt (World Bank Group, 2018). Lebanon’s accreditation system focused on improving quality in the predominantly private hospital sector (Ammar et al., 2007). Egypt has an underfunded, low quality, public healthcare system, and it initially prioritized accreditation of primary healthcare (Rafeh, 2001).

There have been 13 previous literature reviews on accreditation that provide information about the origins of healthcare accreditation programmes and their development, along with many empirical findings related to their implementation (see Table 1). However, none of these reviews focused specifically on the mechanisms by which accreditation policies and practices spread from one country to another, and none made use of a theoretical framework to structure their analysis of the development of accreditation.

Table 1.

Summary of the literature reviews

| Author (year) | Title | Sector | Date/period | # found | Search terms | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El-Jardali (2007) | Hospital accreditation policy in Lebanon | Hospital accreditation | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

|

| Greenfield and Braithwaite (2008) | Health sector accreditation research: a systematic review | Health service accreditation | Prior to 2007 | 66 | Accreditation, healthcare, systematic literature review, quality and safety |

|

| Ciapponi and García Martí (2009) | What are the impacts of health sector accreditation? | SUPPORT Summary of a systematic review: based on Greenfield systematic review in 2008 and relevance of the review for LMICs |

|

|||

| The Haute Autorité de santé (HAS) (2010) | What is the impact of hospital accreditation? International literature review | Hospital accreditation | 1 January 2000 to 31 August 2010 | 56 | Not stated |

|

| Tabrizi et al. (2011) | Advantages and disadvantages of healthcare accreditation models | Health service accreditation | January 1985 to December 2010 | 23 | Quality, Accreditation, Hospital, Healthcare |

|

| Alkhenizan and Shaw (2011) | Impact of Accreditation on the Quality of Healthcare Services: a Systematic Review of the Literature | Health service accreditation | Prior to 2009 | 26 | ‘Accreditation’, ‘health services’, ‘quality’, ‘quality indicators’, ‘quality of healthcare’ and ‘impact’. |

|

| Hinchcliff et al. (2012) | A narrative synthesis of health service accreditation literature | Health service accreditation | Prior to 2012 | 122 |

|

|

| Fortes and Baptista (2012) | Accreditation: tool or policy for health systems organizations? | Health service accreditation | Year 1970–2000s | 36 | Accreditation; Health public policy; Health systems; Quality management |

|

| Alkhenizan and Shaw (2012) | The attitude of healthcare professionals towards accreditation: a systematic review of the literature | Health service accreditation | Prior to 2011 | 17 | ’accreditation’, ‘Health Services’, ‘quality’, ‘quality indicators’, ‘quality of healthcare’, ‘attitude’ and ‘impact’. |

|

| Ng et al. (2013) | Factors affecting implementation of accreditation programmes and the impact of the accreditation process of quality improvement in hospitals: a SWOT analysis | Hospital accreditation | Prior to January 2011 | 26 | ‘Public hospital’, ‘hospital accreditation’ and ‘quality improvement’ |

|

| Brubakk et al. (2015) | A systematic review of hospital accreditation: the challenges of measuring complex intervention effects | Hospital accreditation | Prior to July 2014 (all studies on accreditation/certification in 2006 and this was repeated in 2009, 2013 and 2014) | 4 | Accreditation, Certification, Hospital, Patient Safety, Evaluation |

|

| Nicklin (2015) (Accreditation Canada) | The Value and impact of healthcare accreditation: a literature review | Healthcare accreditation | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

|

| Zarifraftar and Aryankhesal (2016) | Challenges of implementation of accreditation standards for healthcare systems and organizations: a systematic review | Health service accreditation | From January 1960 to March 2014 | 24 | Challenge, Barrier, Hospital, Healthcare Systems, Healthcare Organisations, Implementation of Accreditation standards |

|

Previous reviews drew variously on research published from the 1960s to 2015, although the time periods covered, and the primary literature included by the reviews varied considerably. Four emphasized the introduction and growth of accreditation, described its processes, technical aspects and outcomes. They also looked at the governance of accreditation and how it can be institutionalized in health systems (El-Jardali, 2007; Greenfield and Braithwaite 2008; Fortes and Baptista, 2012; Hinchcliff et al., 2012). Eight reviews explored the value and impact of accreditation, including the impact on the quality of care on overall hospital performance or on a single aspect of performance [Ciapponi and García Martí, 2009; The Haute Autorité de santé (HAS), 2010; Alkhenizan and Shaw, 2011; Tabrizi et al., 2011; Ng et al., 2013; Brubakk et al., 2015; Nicklin, 2015; Zarifraftar and Aryankhesal, 2016]. Two of the reviews from the first group also included some consideration of this. Greenfield and Braithwaite (2008) looked at both accreditation processes and the impact of accreditation on healthcare organizations. Similarly, El-Jardali (2007) described the development of accreditation programmes and the barriers to implementation, with a particular focus on countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR). The remaining review explored the attitude of healthcare professionals towards accreditation (Alkhenizan and Shaw, 2012).

Policy transfer framework

This review uses the Dolowitz and Marsh policy transfer framework to describe how policy ideas develop across time and space. It is the most commonly used framework by researchers to describe the process of policy transfer (James and Lodge, 2003; Benson, 2009; Minkman et al., 2018). It employs a series of questions that may be used to explore the transfer of policies, including: Why does policy transfer? Who is involved in the transfer process? What is transferred? From where is policy transferred? What is the degree of transfer? What are the constraints on policy transfer? How does policy transfer lead to policy failure? (see Table 2). This section highlights some important issues raised by these questions (Dolowitz and Marsh, 2000).

Table 2.

Dolowitz and Marsh policy transfer framework (Dolowitz and Marsh, 2000)

| Why transfer? Want to.....................Have to |

Who is involved in the transfer? | What is transferred? | From where? |

Degree of transfer | Constraints on transfer | How to demonstrate policy transfer? | How transfer leads to policy failure? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voluntary | Mixtures | Coercive | Past | Within a nation | Cross-national | ||||||

| Lesson drawing (perfect rationality) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The transfer can range from being ‘voluntary’ learning or ‘lesson drawing’, to ‘coercive’ transfer of policies or practices (Dolowitz and Marsh, 2000). Policymakers may voluntarily choose to adopt a certain policy or practice that is successful elsewhere and adapt it to their context (Rose, 1991; Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996). Alternatively, governments may be coerced directly by another government or organization to apply a policy change or adopt certain practices against its will, or indirectly to secure grants or loans from a government or other donor agencies (Evans, 2009; Stuckler et al., 2011).

Ugyel and Daugbjerg (2015) classify the transfer agents in developing countries into three categories: (1) domestic civil servants, politicians and bureaucrats, who may look for solutions to their domestic policy issues (Dunlop, 2009); (2) officials affiliated to international organizations established by groups of countries, such as the World Bank, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and International Monetary Fund (IMF), that support public sector reform across developing countries (Stone, 2004; Jones and Kettl, 2003); and (3) non-state actors, including transnational advocacy networks, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), think tanks and ‘epistemic communities’, which are defined by Haas (1992, p. 3) as ‘networks of professionals with recognised expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authoritative claim to policy-relevant knowledge within that domain or issue-area’. The review uses this classification to examine transfer agents in LMICs.

Stone (2004) categorizes the elements to be transferred during the transfer process into two main groups: hard and soft elements. Hard elements are tangible and include legislation, regulations, institutions, policy instruments and programmes; whereas soft elements comprise the ideas, principles, lessons and interpretations obtained from policies. These lessons may be about what to do, or what not to do (Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996). A policy can be transferred endogenously within a country (e.g. between sectors or from one geographical district to others), or exogenously from another country. Bennett (1991, p. 220) suggests that there is ‘a natural tendency to look abroad, to see how other states have responded to similar pressures, to share ideas, to draw lessons and to bring foreign evidence to bear within domestic policy-making processes’.

There are four different degrees of transfer: (1) copying: which is direct and complete transfer; (2) emulation: which involves adapting policies or ideas to fit the local context; (3) inspiration: where a policy in one jurisdiction inspires a policy change in another one, but the final policy does not follow the original; and (iv) combinations: which comprise mixtures of different policies from two countries or more (Dolowitz and Marsh, 2000; Stone, 2000).

Benson (2009) groups constraining factors into four groups directly related to the transfer process: (1) demand side: when policymakers in the recipient country resist the policy change; (2) programmatic: when the complexity of the policy constraints its transferability; (3) contextual: cultural differences between the two political systems (the exporter and the importer); and (4) application: organizational arrangements and institutionalization of the new policy.

Finally, it is not necessarily the case that policies which have been successfully implemented in one country will be similarly successful in another. Dolowitz and Marsh (2000) identify three main ways in which transfer can lead to policy failure: uninformed, incomplete, and inappropriate transfer. Uninformed transfer occurs when the recipient country has insufficient information about the policy or practice being transferred. Incomplete transfer happens when crucial elements of the policy have not been transferred to the recipient country. Inappropriate transfer occurs when the recipient country does not sufficiently consider the cultural differences between it and the exporter country (Dolowitz and Marsh, 2000). Geographic proximity and similarities in cultures, ideologies and resources may raise the chances of policy success and facilitate adaptation between the borrowed policy and the local settings in the recipient country or organization (Walker, 1969; Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996).

Policy transfer thus provides a rich set of concepts which can be used as an analytical tool to analyse the development of a new policy and its processes and outcomes. It is used in this review to explore the mechanisms of the growth of hospital accreditation policy and its adoption by LMICs.

Methods

Search strategy

The literature on hospital accreditation and its development in LMICs was identified from three databases: Medline (OVID), the Cochrane Library and the Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC). The keywords for the search were hospital accreditation and terms for LMICs. Specific countries were identified from the World Bank classification of countries into low-, middle- and higher-income groups based on their levels of income per capita (World Bank Group, 2016). The search was conducted between October 2016 and February 2017.

The search sought to increase sensitivity by using wildcards to include different forms of root words, e.g. accredited, accrediting and accreditation. Wildcards were also used in conjunction with country names to include nationalities, e.g. Albania and Albanian.

The search covered abstracts, keywords and titles. The initial search in the three databases produced 510 articles. The keyword search was supplemented with a snowballing approach until saturation was reached (Greenhalgh and Peacock, 2005). After the original search, a further search was then conducted on Google Scholar using hospital accreditation, low-middle-income countries, developing countries as keywords, plus citation searches for each document found. Online resources of relevant organizations that were known to participate in or fund regional and national accreditation activities (e.g. WHO, USAID and ISQua) were also reviewed. Reference lists of included articles were further screened for any potentially relevant articles not identified in the primary search, in addition to contacting other researchers in the field, who identified additional publications for consideration. All these broadened the literature search and produced another 63 articles; many of which were not published in the journals covered by the three examined databases.

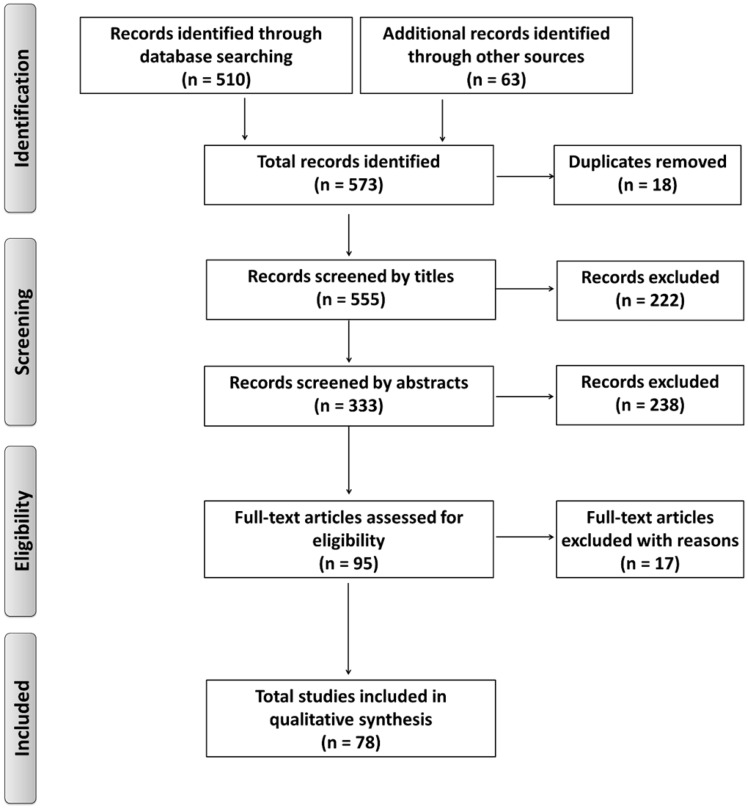

The search was not limited by a specific study design or a certain period. It included both qualitative and quantitative studies that looked at hospital accreditation and its development in any individual LMIC or group of LMICs. Any article that generally discussed accreditation and its processes, its main components, requirements, impacts and common barriers to its implementation and sustainability were also included. The search excluded any article that focused exclusively on accreditation in any setting other than hospitals, such as primary healthcare, specialized hospital departments, disease/medication-specific regulation, and public health and health research. It also excluded any article that discussed the development of accreditation in HICs only, plus non-English language articles. All 573 articles were imported to Endnote and duplicates excluded. The resulting 555 articles were screened by reviewing titles and abstracts. A total number of 95 full texts were obtained, 17 were not relevant, leaving a final number of 78 articles to be included in the analysis, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flowchart of the study selection process (Moher et al., 2009).

Data analysis

A deductive thematic analysis based on policy transfer theory and the questions in the Dolowitz and Marsh framework (see above) was used to analyse the documents found. Text relevant to any of these questions was highlighted and coded. Patterns were identified through an iterative process of bringing relevant information together (Miles and Huberman, 1994). Through this process, contextually sensitive lessons were drawn about how LMICs can develop sustainable hospital accreditation programmes and how international organizations can exploit their role in the field of international policy transfer to be able to support accreditation activities in LMICs.

Results

The findings of the review are structured according to the questions in the policy transfer framework. They are described in more detail in the rest of this section.

Why is accreditation transferred to LMICs?

Accreditation was largely pursued voluntarily as an approach to improve hospital performance (Bukonda et al., 2002; WHO, 2003; Ruelas et al., 2012). There were, however, also a few instances of indirect coercive transfer of accreditation to LMICs (Rafeh, 2001; Bukonda et al., 2002; Legros et al., 2002; Bateganya et al., 2009). Policymakers looked outside their countries, searching for suitable accreditation models to transfer to their home countries to enhance public accountability of healthcare organizations. Some policymakers seeking a ‘quick fix’ for poor hospital performance, decided to transfer accreditation to their home countries, which was limited by time, resources and information.

The literature reports some examples from LMICs in which accreditation programmes were used as an improvement tool for poor hospital performance, a reform instrument for weak health systems, or a regulatory tool for both public and private health sectors (Ammar et al., 2007). Accreditation was also used as part of the implementation of internationally agreed practices such as universal health coverage (UHC), or national policies such as medical tourism (Mate et al. 2014).

Transfer of accreditation as an improvement tool

To face health system challenges in sub-Saharan Africa, a number of Ministries of Health (MOHs) there introduced comprehensive health facility quality standards to their healthcare organizations that set minimum basic requirements for the availability of equipment and use of clinical guidelines. Some organizations in these countries could not comply with these standards due to lack of resources, poor administrative systems and poor organizational inspection (Rowe et al., 2005; Lane et al., 2014). However, governments in these countries persisted in trying to bring quality standards into operation through national health facility accreditation programmes (Bukonda et al., 2002; Lane et al., 2014). For example, Zambia, Uganda and South Africa were reported to have begun extensive reform plans for their health systems and accreditation was essentially included in these plans. Hospitals within these health systems tried to comply with accreditation standards in order to improve the quality of care and promote their public image (Whittaker et al., 2000; Bukonda et al., 2002; Galukande et al., 2016).

The recession of the 1980s in Latin America led to the deterioration of their public sector and its hospitals. In the 1990s, in collaboration with the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO), several countries in Latin America such as Brazil, Chile and Argentina launched their hospital accreditation programmes, in an attempt to strengthen their weak health systems and improve the quality of health services (Arce, 1999; Novaes and Neuhauser, 2000; Legros et al., 2002).

Transfer of accreditation as a regulatory tool

Lebanon and Iran voluntarily chose to use accreditation as a regulatory tool to ensure the quality of healthcare services. Unlike in improvement, accreditation is mandated on all hospitals by law and linked to payments when it is used for regulation (El-Jardali 2007; Kiadaliri et al., 2013; Agrizzi et al., 2016). Countries such as Kenya and Tanzania established a system of National Health/hospital Insurance Funds (NHIF) (Lane et al., 2014). As a result, a number of new accreditation programmes emerged, managed by the NHIFs, where only accredited hospitals could be ‘reimbursed’ for services (Purvis et al., 2010, p. 11).

Accreditation was also used as a mechanism for regulating the private health sector in some LMICs. With lack of inspection by legislative authorities and outdated and poor regulations, the government in India decided to use accreditation to monitor the performance of the private sector (Bhat, 199,9; Nandraj et al., 2001). Similarly, in Lebanon, the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) contracted with private hospitals to manage uninsured patients. With poor quality of care and the high cost of health services as a result of the unregulated private sector and poor governmental control, the MOPH used hospital accreditation as a mechanism to regulate the private sector and improve its service delivery (Ammar et al., 2007).

Transfer of accreditation as part of UHC and medical tourism

Another motive for accreditation in LMICs was medical tourism, e.g. in India (Dastur, 2012) and Jordan (HCAC, 2013). Since patients might limit their search for high-quality health services to accredited hospitals, hospitals were encouraged to participate in accreditation programmes to improve performance and medical outcomes and become medical tourism destinations (Dastur, 2012). This would provide additional income both to the hospital and to the local economy.

The basic principle of UHC is that ‘all people should have access to quality health services they need without facing financial hardship’ (WHO, 2015, p. 2). Public pressure and high social expectations have created a call for equal access to quality healthcare and financial protection from the high costs of health services (WHO, 2015). To achieve this quality of care and ensure value for money, the demand for accreditation has increased and the international move towards UHC raised interest among some LMICs to develop their national accreditation programmes (Shaw, 2015). The payers for UHC—either the governments or insurance funds—support accreditation by providing financial incentives for hospitals to join the programme, and hospitals, in turn, compete to be accredited. Accreditation helps the payers to make informed decisions about which hospitals to include in their payment schemes (Mate et al., 2014).

Indirect coercive transfer of accreditation

The literature shows that the international community can create an indirect coercive transfer by compelling countries, particularly LMICs, to adopt certain policies as a condition of securing funds or loans (Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996; Evans, 2009). This occurred when USAID funded health reform programmes, which specified the inclusion of accreditation in Zambia (Bukonda et al., 2002), Chile (Legros et al., 2002), Indonesia (Broughton et al., 2015), Uganda (Bateganya et al., 2009) and Egypt (Rafeh, 2001).

Who is involved in the transfer of accreditation to LMICs?

This review looked at the agents who were involved in the transfer of hospital accreditation policy to LMICs.

National (state) actors

Officials and national policymakers in LMICs wanted to import the best accreditation model that could fit their national context (Nandraj et al., 2001). Many accreditation programmes started and were managed within the MOHs. This MOH ownership of accreditation programmes, especially in their early stages of development, helped in maintaining the financial and political support needed to sustain the programmes, and in avoiding the financial burden of establishing an independent accreditation body (Mate et al., 2014). The national stakeholders such as civil society organizations, independent hospitals, patient organizations and individual donors also played an important role in supporting their governments’ move towards implementing national accreditation programmes. This, in turn, helped to direct all available national resources towards one common strategic objective that was improving the quality of care (McNatt et al., 2015).

International (non-state) actors

International non-state actors gained the trust of national policymakers through their continuous support to LMICs (Bennett et al., 2015). They used multiple synergistic strategies in the transfer of accreditation policy to LMICs. This occurred through regular regional meetings, annual conferences and academic publications, offering technical support to governments and healthcare organizations and in some cases funding accreditation and its related activities (see Table 3).

Table 3.

The role of international organizations in supporting accreditation in LMICs

| Organization | Activities |

|---|---|

| WHO |

|

| ISQua |

|

| USAID |

|

| JCAHO and JCI |

|

International accreditation experts and individual consultants played a crucial role in the transfer of accreditation to LMICs. For example, consultants and experts from the JCI worked with the Chinese Ministry of Health in 2007 and with the South Korean Hospital Association in 2009 (The Joint Commission, 2017). They helped them through their regular visits, their assistance in developing and revising the standards, and provision of training, which in turn, led to the transfer of knowledge about accreditation and its policy learning, and, in addition, the transfer of new technical skills (Ikbal, 2015).

Donor agencies also played an active role in the introduction of accreditation programmes in LMICs (Mate et al., 2014; Galukande et al., 2016). USAID funded accreditation programmes and provided technical support to governments in many LMICs (see above). USAID also maintained active communication with other actors supportive of accreditation, such as the JCI and ISQua, who further helped in building capacities in LMICs such as in Jordan (USAID, 2013).

The World Bank, WHO and ISQua have worked together for many years to provide support for accreditation programmes in LMICs (Shaw, 2015). They offered technical support to governments and healthcare organizations through regional meetings, conferences, country visits, and publishing of numerous reports, empirical studies and technical working papers explaining accreditation and its processes. ISQua, in particular, produced guidelines for developing accreditation programme and its relevant components.

In conclusion, a number of transfer agents were actively involved in the transfer of accreditation to LMICs including national and international actors. Those actors maintained mutual communications and partnerships to facilitate the uptake of the accreditation policy in limited resources settings.

What is transferred and from where?

There were examples of both soft and hard transfer of accreditation policy. Soft transfer occurred with the growth of the general idea of continuous quality improvement in healthcare in many LMICs (Ammar et al., 2007). The need to tackle challenges in health systems encouraged policymakers to introduce initiatives based on quality improvement concept to their hospitals (Mate et al., 2014). However, they did not necessarily do this through an accreditation system, but sometimes utilized smaller peer review systems as a more appropriate approach to quality improvement with scarce resources (Siddiqi et al., 2012).

The hard transfer of the main components of accreditation programmes (standards development, surveyors, incentives, accreditation body) also occurred. National accreditation programmes that developed in many LMICs were influenced by the success of international programmes in developed countries (Fortes and Baptista, 2012; Aryankhesal, 2016). For example, the accreditation programme in Indonesia was influenced by the Australian programme (Broughton et al., 2015). Similarly, in the EMR, accreditation programmes were commonly influenced by the JCI programme, which established a base in Dubai in 1994 (The Joint Commission, 2017). Governments looked abroad, mainly to these developed countries, to see how they resolved the problem of poor quality of care in their healthcare organizations. They looked at international standards from accreditation bodies in these countries to find the best framework that would be cost-effective, could be adjusted to their national settings and could ensure their quality of care (Whittaker et al., 2000; El-Jardali, 2007; Saleh et al., 2013). Thus, the transfer of hospital accreditation to LMICs was mainly through exogenous sources from developed countries rather than from other LMICs, or endogenously from within the same country.

What is the degree of transfer?

The success of international accreditation models in the developed world inspired many LMICs to change their health policies and make accreditation an integral part of their health systems. JCAHO and its international arm, the JCI programme, were the inspiration for a wide number of accreditation programmes in the developing world, but the final policy did not follow the original framework. Scrivens (1997) claimed that different models of accreditation had successfully developed in LMICs.

Some LMICs emulated international accreditation frameworks. They followed the basic structure, components and processes (Smits et al., 2014); but adapted these frameworks to fit their national contexts and their hospitals. For example, Iran changed its original hospital accreditation programme that was criticized for being structure-based standards. The government developed its updated ‘Accreditation Standards for Hospitals’, which was derived from the JCI standards but included some religious standards that reflected the Iranian national context (Bahadori et al., 2015; Agrizzi et al., 2016).

Also, the Joint Learning Network (JLN) for UHC in their meeting in Bangkok, Thailand, in April 2013 (Mate et al., 2014) reported that members in Ghana, Malaysia, Indonesia, Mali, India and the Philippines discussed approaches to adapting accreditation processes to their local circumstances. This included starting with one basic structural standard such as standards for hand washing and gradually introducing more sophisticated and outcome-oriented standards. Also, using a set of basic standards for all hospitals and gradually adding complex and specialized standards for specialized hospitals such as paediatric hospitals. A third approach was an incremental multi-level accreditation programme where a hospital is granted an entry-level score when it complies with a basic structure such as a policy or procedure, and a full accreditation when the programme is fully implemented and effective (Mate et al., 2014).

Finally, some LMICs looked at a number of available international accreditation models. Although the JCI programme was the main reference for them, they drew on a combination of models from other developed countries such as Australia, Canada and the UK in devising national programmes that fitted their local contexts (Fortes and Baptista, 2012; Aryankhesal, 2016). For example, the accreditation standards in Lebanon have been derived from a combination of seven accreditation programmes used in the USA, Canada, Australia, France, New Zealand, Ireland and the UK (Ammar et al., 2007).

What are the constraints on accreditation transfer to LMICs?

The review identified many barriers to the transfer of hospital accreditation to LMICs. The decision to adopt accreditation was limited by time and scarcity of resources in many LMICs. These limitations represented major challenges, not only to implement accreditation programmes but also to sustain them. The commonly reported constraints in LMICs, according to the categorization in Benson (2009), were contextual and application factors, but not programmatic nor demand factors.

Contextual factors

Policymakers in some LMICs, such as in India and Thailand (Smits et al., 2014), avoided the incompatibilities that could have resulted from cultural differences by adapting international accreditation frameworks to their local contexts. Government policies in LMICs could also be inconsistent, especially if there were frequent changes in governments and ministries, as has happened in Zambia, Liberia and India (Shaw, 2004; Braithwaite et al., 2012), and this hindered the transfer of accreditation. Politicized bureaucracy, corruption and policymakers’ interest in showing their existing policies to be successful were also identified as potentially hindering the transfer of accreditation (Mate et al., 2014; Sax and Marx, 2014). Additionally, a lack of financial resources and premature end to core funding by international donors were considered a major threat to accreditation programmes in LMICs. For example, the ‘Yellow Star’ programme in Uganda was suspended by the government in 2009 after the end of USAID funding in 2005 and the inability of the government to sustain the programme (Bateganya et al., 2009). In Zambia, the programme stopped for the same reason (Lane et al., 2014).

Application factors

The implementation of accreditation remained difficult in many LMICs due to a variety of factors. Poor hospital infrastructure and lack of technology in many LMICs were among the major challenges (Braithwaite et al., 2012; Mate et al., 2014; Bahadori et al., 2015). In addition, many hospitals suffered from inadequately skilled and trained hospital staff and surveyors. Some hospital managers were neither committed to nor enthusiastic about the programme. Running an accreditation programme also required significant administrative resources which hospitals lacked. Such constraining factors were reported in Zambia, Lebanon, Iran and Uganda (Bukonda et al., 2002; Braithwaite et al., 2012; Saleh et al., 2013; Mate et al., 2014; Bahadori et al., 2015; Galukande et al., 2016; Zarifraftar and Aryankhesal, 2016).

What is the outcome of accreditation transfer to LMICs?

Not all transfer cases are successful. Although transfer can promote the development of policies, there is still a risk of implementation failure or lack of sustainability (Dolowitz and Marsh, 2000). Disappointingly, this was a relatively frequent occurrence in the transfer of accreditation to LMICs such as in the cases of Uganda (Bateganya et al., 2009) and Zambia (Lane et al., 2014). As reported by Purvis et al. (2010), many accreditation programmes could not sustain their viability in countries with limited resources. The reasons for such accreditation policy failure are examined using the classification of policy failure as described by Dolowitz and Marsh (2000).

Uninformed transfer

This occurred when LMICs lacked the information needed to guide their accreditation processes and practices, e.g. standards and guidelines (Hort et al., 2013). To develop a new accreditation programme, governments in LMICs were said to be ‘left to reinvent the wheel’ in basic areas such as standards development, surveyor training programmes and structuring of incentives (Smits et al., 2014). Subsequently, this led to poor policy learning and confusion on handling accreditation and its outcomes at the organizational level as reported in the Zambian experience (Bukonda et al., 2002). In addition, in Thailand, lack of surveyors’ training led to criticisms of ‘subjective’ evaluation by surveyors which influenced the survey process and its reported outcomes (Sriratanaban and Ungsuroat, 2000; Pongpirul et al., 2006).

Incomplete transfer

Sometimes key elements of accreditation were omitted when the policy was transferred. Some LMICs developed standards that mainly considered input indicators while ignoring other indicators such as those related to patient safety, process or quality performance (Broughton et al., 2015). It was also a challenge to establish and administer an accreditation body independent from the MOH (Mate et al., 2014; Shaw, 2015). One study that looked at the development of accreditation in Pakistan identified as a major challenge the establishment of an accreditation body that could transparently manage all accreditation processes (Sax and Marx, 2014).

Furthermore, in the cases where payments were linked to the NHIF, conflict of interest arose with the automatic accreditation of all public hospitals such as in Kenya in 2009, when private hospitals needed to conduct an initial assessment to be accredited, while, public hospitals automatically obtained accreditation (Lane et al., 2014). Mandating accreditation on all hospitals in some LMICs led to a distortion of the philosophy of accreditation as a voluntary tool promoting the concept of continuous quality improvement (Pongpirul et al., 2006).

Policy success

The literature highlighted some factors that supported the successful transfer of accreditation policy to LMICs. Political support and commitment of the national healthcare leaders was an essential element in developing hospital accreditation programmes in many LMICs (Novaes and Neuhauser, 2000), this was evident in Jordan (HCAC, 2013). MOH ownership helped in maintaining the financial and political support needed to develop and sustain the programmes (Cleveland et al., 2011). Also, approaches like linking accreditation to reimbursement or insurance schemes, the availability of incentives such as recognition of a hospital or one of its staff and designating hospitals as medical tourism destinations, also helped with the success of accreditation programmes and their sustainability in some LMICs (Mate et al., 2014).

Collaboration between LMICs and some international organizations and accreditation agencies (see Table 3), and stakeholders engagement also supported the development of accreditation programmes and facilitated the implementation process (Cleveland et al., 2011; Ng et al., 2013). For example, in Thailand, stakeholders such as patient organizations and national insurance companies were involved in the development of national accreditation standards and strengthening the capacity of the national accreditation programme (Pongpirul et al., 2006).

Discussion

The primary goal of this review was to provide deeper understanding and interpretations of the development of hospital accreditation in LMICs through an extensive analysis of policy transfer, its processes and outcomes. The review has taken into account the different local contexts of LMICs and the implications for policy transfer. Policy transfer provided a useful analytical framework to examine the research questions and to explore the transfer process in LMICs, and how governments and policymakers reacted to and interacted with accreditation as a new policy.

Interestingly, despite limited resources in many LMICs, governments voluntarily chose to adopt hospital accreditation as an improvement tool for their hospitals. The decision to use accreditation was based on ‘bounded rationality’ since it was limited by insufficient financial resources and lack of experience, technology and information about accreditation. This review concluded that the lack of financial resources remains a major challenge to many LMICs that seek to develop their national accreditation systems. This concurs with the findings of Purvis et al. (2010), Shaw et al. (2010) and Mate et al. (2014) that implementation and sustainability of accreditation programmes in LMICs are very challenging with the unavailability of resources and poor hospital infrastructure. However, in addition, this review examined how countries were able to develop and implement their accreditation programmes within these limited resources and drew lessons for other countries with similar settings, which may help them to establish and sustain their accreditation programmes.

The literature on policy transfer identifies geographic neighbours as the main source of policy transfer and lesson drawing (Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996). However, this geographic proximity has not been reported in the literature to play a significant role in the transfer of accreditation policy to LMICs. The transfer of accreditation was mainly exogenous from the developed world. International accreditation frameworks from the USA, Canada, Australia and the UK have transferred to many LMICs, particularly the JCI programme from the USA. Meanwhile, countries within the same region were motivated by the support of international actors such as the WHO to develop their accreditation programmes. Regular regional meetings by the WHO offices such as EMRO and PAHO supported the growth of accreditation among countries in their regions and helped with accreditation policy learning. The voluntary transfer of accreditation to LMICs also helped in learning accreditation policy, which was also supported by a number of international actors such as the JCI, ISQua and USAID. This, in turn, helped to avoid the uninformed transfer.

The review found that national accreditation programmes were typically inspired by international frameworks. In many cases, governments emulated the accreditation policy but avoided the ‘lift and shift’ of these international standards that could lead to inappropriate transfer and policy failure. They successfully paid attention to the economic, social, political and cultural settings in their countries and tailored the international accreditation models to fit their hospitals, pursuing approaches such as those advocated by the JLN (Mate et al., 2014).

These approaches could be considered as a particular form of emulation of the accreditation policy where there is some moderation of the standards and a sense of progression over time in order to fit with the realities of lack of resources in some hospitals. It might be helpful if international actors could encourage such approaches when funding accreditation programmes in LMICs since many LMICs failed to sustain their accreditation programmes after donor funding ends. Encouraging such approaches might be considered as an appropriate involvement of international actors to support both the transferability and sustainability of accreditation in LMICs.

Government officials in LMICs also supported the voluntary transfer of accreditation to their countries, and accreditation programmes were managed within the MOHs in most LMICs, especially during the early stages. A study conducted by Braithwaite et al. (2012) to compare accreditation programmes in LMICs with those in HICs found that in 60% of the respondents from 20 LMICs, accreditation was managed within the MOH in comparison to only 8% in respondents from HICs, and justified this as being a governmental response to the lack of resources in LMICs and an approach to ensure the viability of their accreditation programmes. This MOH ownership supported the sustainability of many accreditation programmes in LMICs (Smits et al., 2014).

WHO has recommended that LMIC governments participate in standards development, as the public sector is the predominant healthcare provider in many of these countries (Al-Assaf, 2007; Maamari, 2007). Similarly, Nandraj and colleagues (2001) argue that the MOH ownership of the accreditation programme does not contradict its main role as a healthcare regulator. Instead, it can reinforce both a culture of change and quality improvement within the national health system. In contrast, Shaw (2004) argues that many successful accreditation programmes are independent of the MOHs and have their own legal responsibilities and their governance system. Consequently, Maamari (2007) raises the need to keep a balance between the independence of the accreditation body and the accountability for its recommendations for healthcare organizations in order to maintain its credibility and authority. One of the recommendations of this review is to start the national accreditation programme with the MOH as the main governing body of the programme to ensure reliability and maintenance. An independent accrediting body can then be set up once the programme is well-established and functioning, in order to avoid conflict of interest, especially if the public health sector is the predominant healthcare provider.

Strong government commitment and political support, the MOH ownership, linking accreditation to payments and partnering with international actors appear to be the most common factors that facilitated the transfer of hospital accreditation to LMICs. Partnering supported the synchronization with and adaptation from international standards, and the training of local surveyors. In turn, these helped with the sustainability of the programme (Ng et al., 2013). Contextual and application factors were the most common barriers to the transfer of accreditation, mainly due to the lack of financial resources. This, in turn, led to an incomplete transfer of some crucial elements of the accreditation programme such as the unavailability of financial incentives and the inability to develop and manage a national accreditation body, with an ongoing debate about whether it should be independent of the MOH or not.

This study contributes to the literature by developing a thorough and updated review of the literature on hospital accreditation and its processes, identifying key requirements and common barriers to the implementation and sustainability of accreditation in LMICs. The review contributes to the body of knowledge regarding both accreditation and international policy transfer.

The literature on accreditation lacks the theory development that can explain the growth of accreditation and its processes and outcomes (Greenfield and Braithwaite, 2008). The review addresses this by using the Dolowitz and Marsh policy transfer framework as an analytical tool. Few studies have explored the development of accreditation and its components in LMICs. The review addresses this gap by using a structured analytic framework to consider examples from LMICs in detail.

Most cases of international policy transfer in the literature have described what was transferred rather than how the transfer process proceeded (Mossberger and Wolman, 2003). This review analysed the process of accreditation policy transfer to LMICs and its outcomes. The Policy transfer framework provided a useful tool for examining how accreditation has transferred from one setting to another and how policymakers in LMICs could adopt the policy in their home countries and how they adapted it to their local contexts. Furthermore, the review looked at accreditation policy outcomes from both the success and failure angles, going beyond the Dolowitz and Marsh framework, which focuses only on the reasons for policy failure.

Limitations of the study

There are some limitations to this literature review that need to be considered. Limiting the search to only English language articles might have led to missing articles from LMICs in Latin America, Africa and South Asia. There were also some aspects which the review did not consider due to time constraints, such as how governments in LMICs could relate accreditation policy to their national health policies. This might benefit from further research.

Recommendations for research and practice

Future empirical research on accreditation underpinned by explicit theory would be valuable so that it is easier to assess the relevance of research to different countries and for studies to build on each other’s findings. Further research is also needed to study the background of some emerging policies in LMICs, e.g. UHC and medical tourism and their linkage to accreditation in these countries, as the literature on these areas was sparse. Such research would also be an opportunity to further develop this review’s analysis of the role of international actors in policy transfer of accreditation to LMICs.

Since the lack of financial resources is a major challenge to accreditation in LMICs, further research is needed to analyse the cost-benefit of accreditation programmes in countries with limited resources. There is a need to explore how to reduce the administrative costs of accreditation programmes, or perhaps how to share these costs with NGOs and other international actors. Research on how to enhance the role of these organizations to better support accreditation and quality initiatives in LMICs is also indicated. It may be useful to explore the existing international networks that are involved in accreditation transfer, how they operate and to what extent accreditation as a policy can be shaped by national and international structures.

Conclusion

Many LMICs have developed national accreditation programmes, but lack of financial resources remains a key constraint to the success of accreditation and its sustainability in LMICs. The review concludes that political support and government commitment are critical to developing and sustaining national accreditation programmes in countries with limited resources. MOH ownership can be effective in supporting the programme during its early stages giving it prestige, accountability and authority.

Governments in LMICs might use alternative accreditation models such as incremental multi-level accreditation programmes to encourage hospitals to comply with accreditation standards; they can gradually proceed to full accreditation based on the infrastructure of the hospitals and the availability of funds. International actors, particularly donor agencies, should give greater emphasis to providing ongoing support to LMICs to develop and sustain accreditation. Research also needs to focus not only on the introduction of accreditation programmes and their implementation processes but equally importantly on how to sustain them.

Acknowledgements

This research is self-funded by the main researcher as a part of her PhD study at the University of Manchester.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.]

Ethical approval. No ethical approval was required for this study.

References

- Agrizzi D, Agyemang G, Jaafaripooyan E.. 2016. Conforming to accreditation in Iranian hospitals. Accounting Forum 40: 106–24. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Assaf A. 2007. Certification, licensure and accreditation. In: Al-Assaf A, Seval A (eds). Healthcare Accreditation Handbook.A Practical Guide. 2nd edn.18–38.http://mighealth.net/eu/images/6/6c/Acc.pdf, accessed 18 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhenizan A, Shaw C.. 2011. Impact of accreditation on the quality of healthcare services: a systematic review of the literature. Annals of Saudi Medicine 31: 407–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhenizan A, Shaw C.. 2012. The attitude of health care professionals towards accreditation: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Family and Community Medicine 19: 74–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammar W, Wakim IR, Hajj I.. 2007. Accreditation of hospitals in Lebanon: a challenging experience. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 13: 138–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arce H. 1999. Accreditation: the Argentine experience in the Latin American region. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 11: 425–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryankhesal A. 2016. Strategic faults in the implementation of hospital accreditation programmes in developing countries: reflections on the Iranian experience. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 5: 515–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahadori M, Ravangard R, Alimohammadzadeh K.. 2015. The accreditation of hospitals in Iran. Iranian Journal of Public Health 44: 295–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateganya M, Hagopian A, Tavrow P, Luboga S, Barnhart S.. 2009. Incentives and barriers to implementing national hospital standards in Uganda. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 21: 421–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett C. 1991. Review article: what is policy convergence and what causes it? British Journal of Political Science 21: 215–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S, Dalglish SL, Juma PA, Rodríguez DC.. 2015. Altogether now…understanding the role of international organisations in iCCM policy transfer. Health Policy and Planning 30: ii26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson D. 2009. Review Article: Constraints on Policy Transfer Working paper—the Centre for Social and Economic Research on the Global Environment. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/48824 accessed 20 September 2018.

- Bhat R. 199. Characteristics of private medical practice in India: a provider perspective. Health Policy and Planning 14: 26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite J, Shaw C, Moldovan M. et al. 2012. Comparison of health service accreditation programmes in low- and middle-income countries with those in higher income countries: a cross-sectional study. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 24: 568–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton E, Achadi A, Latief K. et al. 2015. Indonesia Hospital Accreditation Process Impact Evaluation: Midline Report Technical Report Published by the USAID ASSIST Project. Bethesda, MD: University Research Co., LLC (URC). https://www.usaidassist.org/resources/indonesia-hospital-accreditation-process-impact-evaluation-midline-report, accessed 20 October 2018.

- Brubakk K, Vist GE, Bukholm G, Barach P, Tjomsland O.. 2015. A systematic review of hospital accreditation: the challenges of measuring complex intervention effects. BMC Health Services Research 15: 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukonda N, Tavrow P, Abdallah H, Hoffner K, Tembo J.. 2002. Implementing a national hospital accreditation programme: the Zambian experience. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 14: 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciapponi A, García Martí S.. 2009. What Are the Impacts of Health Sector Accreditation? A SUPPORT Summary of a systematic review. www.support-collaboration.org/summaries.htm, accessed 4 March 2016.

- Cleveland EC, Dahn BT, Lincoln TM. et al. 2011. Introducing health facility accreditation in Liberia. Global Public Health 6: 271–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dastur F. 2012. Hospital accreditation: a certificate of proficiency for healthcare institutions. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 60: 12–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolowitz D, Marsh D.. 1996. Who learns from whom: a review of the policy transfer literature. Political Studies 44: 343–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dolowitz D, Marsh D.. 2000. Learning from abroad: the role of policy transfer in contemporary policy making. Governance 13: 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop C. 2009. Policy transfer as learning: capturing variation in what decision-makers learn from epistemic communities. Policy Studies 30: 289–311. [Google Scholar]

- El-Jardali F. 2007. Hospital accreditation policy in Lebanon: its potential for quality improvement. Le Journal Medical Libanais. The Lebanese Medical Journal 55: 39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M. 2009. Policy transfer in critical perspective. Policy Studies 30: 243–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fortes MT, Baptista TW.. 2012. Accreditation: tool or policy for health systems organisations? Acta Paulista de Enfermagem 25: 626–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fortes MT, Mattos RA, Baptista TW.. 2011. Accreditation or accreditations? A comparative study on accreditation in France, United Kingdom and Cataluña. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira 57: 240–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galukande M, Katamba A, Nakasujja N. et al. 2016. Developing hospital accreditation standards in Uganda. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 31: E204–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield D, Braithwaite J.. 2008. Health sector accreditation research: a systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 20: 172–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield D, Pawsey M, Hinchcliff R, Moldovan M, Braithwaite J.. 2012. The standard of healthcare accreditation standards: a review of empirical research underpinning their development and impact. BMC Public Health Services Research 12: 329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Peacock R.. 2005. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: an audit of primary sources. BMJ 331: 1064–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas PM. 1992. Introduction: epistemic communities and international policy coordination. International Organization 46: 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare Accreditation Council in Jordan (HCAC). 2013. Establishing a national accreditation system in a middle-income country: the Jordan experience. Unpublished.

- Hinchcliff R, Greenfield D, Moldovan M. et al. 2012. Narrative synthesis of health service accreditation literature. BMJ Quality & Safety 21: 979–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hort K, Djasri H, Utarini A.. 2013. Regulating the Quality of Healthcare: Lessons from Hospital Accreditation in Australia and Indonesia. Melbourne: Nossal Institute for Global Health; http://manajemenrumahsakit.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/WP_28-Hospital-accreditation-Aust-Indonesia.pdf, accessed 2 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ikbal F. 2015. Beyond accreditation: issues in healthcare quality. International Journal of Research Foundation of Hospital and Healthcare Administration 3: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- James O, Lodge M.. 2003. The limitations of ‘policy transfer’ and ‘lesson drawing’ for public policy research. Political Studies Review 1: 179–93. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MC, Schellekens O, Stewart J. et al. 2016. SafeCare: an innovative approach for improving quality through standards, benchmarking, and improvement in low- and middle-income countries. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 42: 350–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Commission. 2017. History of the Joint Commission https://www.jointcommission.org/about_us/history.aspx, accessed 13 June 2018.

- Jones LR, Kettl DF.. 2003. Assessing public management reform strategy in an international context. International Public Management Review4: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kiadaliri AA, Jafari M, Gerdtham U-G.. 2013. Frontier-based techniques in measuring hospital efficiency in Iran: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. BMC Health Services Research 13: 312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane J, Barnhart S, Luboga S. et al. 2014. The emergence of hospital accreditation programmes in East Africa: lessons from Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania. Global Journal of Medicine and Public Health 3: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Legros S, Massoud R, Urroz O.. 2002. The Chilean legacies in healthcare quality. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 14: 83–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maamari N. 2007. Hospital accreditation In: Al-Assaf A, Seval A (eds). Healthcare Accreditation Handbook. A Practical Guide. 2nd edn.277–345. http://mighealth.net/eu/images/6/6c/Acc.pdf, accessed 18 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mate KS, Rooney AL, Supachutikul A, Gyani G.. 2014. Accreditation as a path to achieving universal quality health coverage. Globalization and Health 10: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNatt Z, Linnander E, Endeshaw A. et al. 2015. A national system for monitoring the performance of hospitals in Ethiopia. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 93: 719–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB., Huberman AM.. 1994. Data management and analysis methods In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds). Handbook of Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications, 428–44. [Google Scholar]

- Minkman E, van Buuren MW, Bekkers VJ.. 2018. Policy transfer routes: an evidence-based conceptual model to explain policy adoption. Policy Studies 39: 222–50. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 151: 264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morena-Serra R. 2012. Does progress towards universal health coverage improve population health? The Lancet 380: 917–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossberger K, Wolman H.. 2003. Policy transfer as a form of prospective policy evaluation: challenges and recommendations. Public Administration Review 63: 428–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nandraj S, Khot A, Menon S, Brugha R.. 2001. A stakeholder approach towards hospital accreditation in India. Health Policy and Planning 16: 70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng K, Leung GK, Johnston JM, Cowling BJ.. 2013. Factors affecting the implementation of accreditation programmes and the impact of the accreditation process on quality improvement in hospitals: a SWOT analysis. Hong Kong Medical Journal 19: 434–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklin W. 2015. The Value and Impact of Healthcare Accreditation: A Literature Review Accreditation Canada, 2008 (Updated April 2015). http://hpm.fk.ugm.ac.id/wp/wp-content/uploads/Sesi-8-BAHAN-BACAAN-The-Value-and-Impact-of-Health-Care-Accreditation.pdf, accessed 17 July 2017.

- Novaes H, Neuhauser D.. 2000. Hospital accreditation in Latin America. Pan American Journal of Public Health 7: 425–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongpirul K, Sriratanaban J, Asavaroengchai S, Thammatach-Aree J, Laoitthi P.. 2006. Comparison of healthcare professionals’ and surveyors’ opinions on problems and obstacles in implementing a quality management system in Thailand: a national survey. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 18: 346–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purvis GP, Jacobs D, Kak N.. 2010. . International Healthcare Accreditation Models, and Country Experiences: Introductory Report on Options for the Republic of South Africa. Pretoria: University Research Co., LLC; https://www.usaidassist.org/sites/assist/files/international_accreditation_models_feb10_0.pdf, accessed 18 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rafeh N. 2001. Accreditation of Primary Health Care Facilities in Egypt: Programme Policies and Procedures Technical Report No. 65. Bethesda, MD: Partnerships for Health Reform Project, Abt Associates Inc. http://www.phrplus.org/Pubs/te65fin.pdf accessed 2 January 2016.

- Rose R. 1991. What is lesson-drawing? Journal of Public Policy 11: 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe AK, Savigny D, Lanata C, Victora C.. 2005. How can we achieve and maintain high‐quality performance of health workers in low resource settings? The Lancet 366: 1026–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruelas E, Dantes OG, Leatherman S, Fortune T, Gay-Molina JG.. 2012. Strengthening the quality agenda in healthcare in low- and middle-income countries: questions to consider. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 24: 553–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh SS, Bou Sleiman J, Dagher D, Sbeit H, Natafgi N.. 2013. Accreditation of hospitals in Lebanon: is it a worthy investment? International Journal for Quality in Health Care 25: 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sax S, Marx M.. 2014. Local perceptions of factors influencing the introduction of international healthcare accreditation in Pakistan. Health Policy and Planning 29: 1021–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrivens E. 1997. Assessing the value of accreditation systems. The European Journal of Public Health 7: 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw C. 2000. External quality mechanisms for healthcare: summary of the ExPeRT project on visitation, accreditation, EFQM and ISO assessment in European Union countries. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 3: 169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw C. 2003. Evaluating accreditation. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 15: 455–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw C. 2004. Toolkit for Accreditation Programmes: Some Issues in the Design of External Assessment and Improvement Systems. Dublin: ISQua, ALPHA Council for the World Bank; http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.495.1428&rep=rep1&type=pdf, accessed 4 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw C. 2015. Accreditation is not a stand-alone solution. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 21: 226–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw C, Kutryba B, Braithwaite J, Bedlicki M, Warunek A.. 2010. Sustainable healthcare accreditation: messages from Europe in 2009. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 22: 341–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi S, Elasady R, Khorshid I. et al. 2012. Patient Safety Friendly Hospital Initiative: from evidence to action in seven developing country hospitals. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 24: 144–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits H, Supachutikul A, Mate KS.. 2014. Hospital accreditation: lessons from low- and middle-income countries. Globalization and Health 10: 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriratanaban J, Ungsuroat Y.. 2000. Evaluation of the Hospital Accreditation Project. Nonthaburi: Health Systems Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Stone D. 2000. Non-governmental policy transfer: the strategies of independent policy institutes. Governance 13: 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Stone D. 2004. Transfer agents and global networks in the “transnationalization” of policy. Journal of European Public Policy 11: 545–66. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckler D, Basu S, McKee M.. 2011. International monetary fund and aid displacement. International Journal of Health Services 41: 67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabrizi JS, Gharibi F, Wilson AJ.. 2011. Advantages and disadvantages of healthcare accreditation models. Health Promotion Perspectives 1: 1–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission. 2017. History of The Joint Commission Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/about_us/history.aspx, accessed 13 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The Haute Autorité de santé (HAS). 2010. What Is the Impact of Hospital Accreditation? International Literature Review. Paris: MATRIX Knowledge group; https://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2011-10/synth-matrix_ang_v2.pdf, accessed 18 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ugyel L, Daugbjerg C.. 2015. Voluntary policy transfer in developing countries: international and domestic agents and process dynamics. IGPA Research Seminar Series. Lhawang Ugyel & Carsten Daugbjerg. In International Conference on Public Policy, 1–14.

- USAID. 2013. Jordan Healthcare Accreditation Project, Final Report. https://jordankmportal.com/resources/final-report-of-jordan-healthcare-accreditation-project-2013, accessed 1 May 2016.

- Walker J. 1969. The diffusion of innovations among the American states. The American Political Science Review 33: 880–99. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker S, Green-Thompson RW, Mccusker I, Nyembezi B.. 2000. Status of healthcare quality review programme in South Africa. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 3: 247–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. 2016. Countries and Economies https://data.worldbank.org/country, accessed 12 December 2016.

- World Bank Group. 2018. GDP per Capita (Current US$)—Egypt, Arab Rep https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD? locations=EG, accessed 8 December 2019.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2003. Quality and Accreditation in Health Services: A Global Review Geneva. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2003/WHO_EIP_OSD_2003.1.pdf, accessed 2 February 2016.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2015. Universal Health Coverage: Moving Towards Better Health. WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, July 2015, Manila, Philippines. Available at: https://iris.wpro.who.int/handle/10665.1/12124, accessed 15 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zarifraftar M, Aryankhesal. 2016. Challenges of implementation of accreditation standards for healthcare systems and organisations: a systematic review. Journal of Management Sciences2: 191–201. [Google Scholar]