Abstract

Defects in the function of primary cilia are commonly associated with the development of renal cysts. On the other hand, the intact cilium appears to contribute a cystogenic signal whose effectors remain unclear. As integrin-β1 is required for the cystogenesis caused by the deletion of the polycystin 1 gene, we asked whether it would be similarly important in the cystogenetic process caused by other ciliary defects. We addressed this question by investigating the effect of integrin-β1 deletion in a ciliopathy genetic model in which the Ift88 gene, a component of complex B of intraflagellar transport that is required for the proper assembly of cilia, is specifically ablated in principal cells of the collecting ducts. We showed that the renal cystogenesis caused by loss of Ift88 is prevented when integrin-β1 is simultaneously depleted. In parallel, pathogenetic manifestations of the disease, such as increased inflammatory infiltrate and fibrosis, were also significantly reduced. Overall, our data indicate that integrin-β1 is also required for the renal cystogenesis caused by ciliary defects and point to integrin-β1-controlled pathways as common drivers of the disease and as possible targets to interfere with the cystogenesis caused by ciliary defects.

Keywords: ciliopathy, cilium, cystic kidney, Ift88, integrin

INTRODUCTION

Nonmotile or primary cilia are specialized apical cell membrane protrusions that assemble around the microtubule-based axoneme, which stems from the basal body. This is a specialized centriole around which a number of proteins converge to form a structurally defined domain of the cilium known as the transition zone, which acts as a gatekeeper for the regulated movement of the ciliary components (1). The function of primary cilia is to convert extracellular physical, chemical, and mechanical stimuli into a multitude of cellular signaling pathways that control cell proliferation, cytoskeletal rearrangement, cell metabolism, and intracellular trafficking. Consequently, defects in ciliary proteins have profound effects on the development and function of many organs and result in a variety of rare, syndromic conditions collectively referred to as ciliopathies. Pathognomonic to many ciliopathies are kidney cyst formation and renal fibrosis. In fact, the observation of renal cystic disease in the absence of normal ciliogenesis provided the first clue of the possible function of the primary cilium in kidney development (21, 30), and ample evidence has since accumulated on the role of cilia in the regulation of different signaling pathways that control development.

While defects of virtually any ciliary protein result in renal cystogenesis, it was shown that intact cilia support a cyst growth-promoting pathway, referred to as cilia-dependent cyst activation (18). The nature of this signal remains unclear, but it is likely independent of the function of polycystin-1 or polycystin-2 (Pkd1 and Pkd2 genes, respectively), whose mutations cause autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (18), a life-threatening disorder characterized by the formation of bilateral fluid-filled renal cysts, fibrosis, and progressive parenchymal loss that eventually cause organ failure. In fact, it has been suggested that Pkd1 may function by inhibiting cilia-dependent cyst activation (16, 18). However, thus far, no mediator of this cystic pathway has been identified.

We showed that the severe cystic phenotype caused by deletion of Pkd1 was reversed by the codeletion of integrin-β1 (Itgb1 gene) in a conditional mouse model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, indicating that integrin-β1-dependent signaling was required for the cystogenesis induced by loss of Pkd1 (15). The dramatic effect of integrin-β1 knockout also suggested that the mechanism of inhibition may be acting very early in Pkd1-dependent cystic signaling. This led us to ask whether integrin-β1 would be required also in cystic disease caused by ciliary defects. We addressed this question using a conditional model of ablation of Ift88, a component of complex B of intraflagellar transport that is required for the proper assembly of cilia. We show that the simultaneous deletion of integrin-β1 in an Ift88 knockout background significantly reduced the cilium-dependent cystic phenotype, thus suggesting that integrin-β1 signaling functions downstream of cilia-dependent cyst activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

B6.129P2-Ift88tm1Bky/J (JAX stock no. 022409) (10), B6.129-Itgb1tm1Efu/RthsnJ (JAX stock no. 034193) (24), and B6.Cg-Tg(Aqp2-cre)1Dek/J (JAX stock no. 006881) (19) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and crossed to generate collecting duct-specific Ift88fl/fl;Tg(Aqp2-cre) and Itgb1fl/fl;Tg(Aqp2-cre) single-knockout mice and Ift88fl/fl;Itgb1fl/fl;Tg(Aqp2-cre) double-knockout mice (hereafter referred to as Ift88 KO, Itgb1 KO, and Ift88;Itgb1 DKO mice, respectively). Genotyping was confirmed by PCR according to Jackson Laboratory’s protocol. Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Blood urea nitrogen measurement and cystic index.

Blood urea nitrogen was measured from sera collected from 9-mo-old animals using the QuantiChrom Urea Assay Kit (DIUR-100, Bioassay Systems, Hayward, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cystic index was determined assessing the cyst area relative to the total sample’s surface using ImageJ.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence.

Mouse kidneys were fixed by perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, paraffin embedded, and cryosectioned. For staining in paraffin tissue, dewaxed sections were subjected to heating in 20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 9.0), 1 mM EDTA, or 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 30 min. Sections were blocked in 5% normal goat serum for 30 min. Incubation in primary antibodies was carried out overnight at 4°C followed by incubation in the appropriate secondary antibodies and rhodamine- or FITC-conjugated Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) to stain collecting duct epithelial cells. Sections were then incubated in 0.1% Sudan black B in 70% ethanol to reduce background fluorescence and finally mounted in DAPI-fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL). The following primary antibodies were used at the indicated dilutions: α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; 1:200, catalog no. 5694), Ki-67 (1:100, catalog no. 15580), CD4 (1:100, catalog no. 25475, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), F4/80 (1:50, catalog no. 14-4801-82, eBioscience, San Diego, CA), major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II; 1:100, catalog no. 32247, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), CD206 (1:100, catalog no. 123001, BioLegend, San Diego, CA), and CD8 (1:100, catalog no. 98941, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA).

TUNEL assay.

Deparaffinized and rehydrated sections were incubated with 20 μg/mL proteinase K in 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.4) for 15 min at room temperature. Slides were rinsed with PBS-Tween 20 and incubated with 3% H2O2 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature to block endogenous peroxidase activity followed by PBS-Tween 20 for washing. Slides were then incubated with a mixture of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) and biotin-16-dUTP (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) in terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in a humidified chamber at 37°C for 2 h. After incubation, slides were washed with PBS-Tween 20 and incubated with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase in a humidified chamber for 20 min at room temperature. After an additional wash with PBS, slides were incubated in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories) and counterstained with hematoxylin. DNase I-treated slides were used as a positive control.

Sirius red staining and fibrotic area measurement.

Tissue slides were stained with the Picro Sirius Red Stain Kit (Abcam) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The stained fibrotic area was measured as a percentage of the total area using ImageJ.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from wild-type, Itgb1 KO, Ift88 KO, and Ift88;Itgb1 DKO kidneys of of 9-mo-old mice using a direct-Zol RNA miniprep kit (Zymo, Irvine, CA). cDNA synthesis was performed using RNA to cDNA EcoDry Premix (Clontech, Kyoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative PCR was performed with SYBR green (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The specific primers used in quantitative PCRs are shown in Table 1. Relative expression was normalized to that of the housekeeping ribosomal protein S11 gene for analysis.

Table 1.

List of primers used in the quantitative RT-PCR gene expression analyses

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| Ccl2 | 5′-GACCCGTAAATCTGAAGCTAA-3′ | 5′-CACACTGGTCACTCCTACAGAA-3′ |

| Fibronectin | 5′-CTTTGGCAGTGGTCATTTCAG-3′ | 5′-ATTCTCCCTTTCCATTCCCG-3′ |

| Collagen type I | 5′-CATAAAGGGTCATCGTGGCT-3′ | 5′-TTGAGTCCGTCTTTGCCAG-3′ |

| NGAL | 5′-TCCTCAGGTACAGAGCTACAA-3′ | 5′-GCTCCTTGGTTCTTCCATACA-3′ |

| KIM-1 | 5′-ATGGCACTGTGACATCCTC-3′ | 5′-ACCACGCTTAGAGATGCTG-3′ |

| Ccl20 | 5′-CTTGCTTTGGCATGGGTACT-3′ | 5′-TCAGCGCACACAGATTTTCT-3′ |

| Cxcl5 | 5′-TCCAGCTCGCCATTCATGC-3′ | 5′-TTGCGGCTATGACTGAGGAAG-3′ |

| Timp1 | 5′-TGGGTTCCCCAGAAATCAACG-3′ | 5′-ACAGAGGCTTTCCATGACTGG-3′ |

| Il-1β | 5′-GCAACTGTTCCTGAACTCAACT-3′ | 5′-ATCTTTTGGGGTCCGTCAACT-3′ |

| Rps11 | 5′-TGCAGTCGATAAGGAAACCC-3′ | 5′-TTGCCAGTTTCTCCAAGTAGG-3′ |

Ccl, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule-1; Cxcl, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand; Timp, tissue inhibitor of metalloprotenase; Rps11, ribosomal protein S11.

Statistical analysis.

All data are presented as means ± SE. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison post test or Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test were used to analyze intergroup differences using Prism 7 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

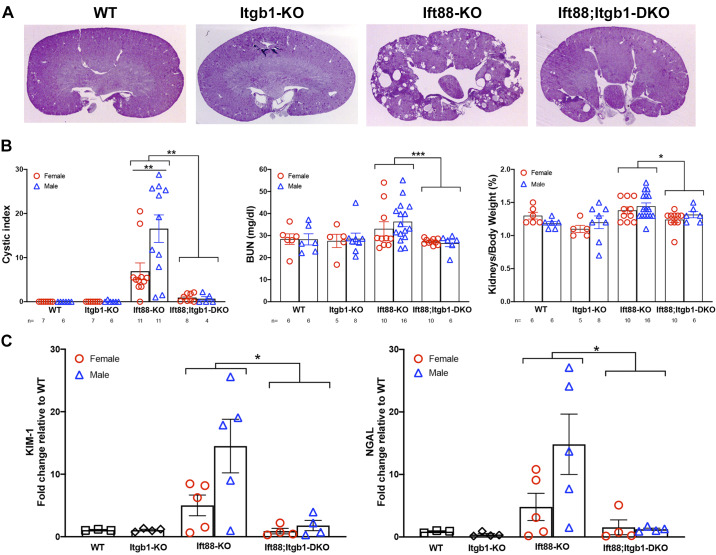

To determine whether integrin-β1 plays any role in the cystogenesis caused by ciliary defects, we crossed Ift88fl/fl, Itgb1fl/fl, and Aqp2-CreTg mice to generate conditional Ift88fl/fl;Aqp2-CreTg and Itgb1fl/fl;Aqp2-CreTg single-knockout mice (hereafter referred to as Ift88 KO and Itgb1 KO mice, respectively) and Ift88fl/fl;Itgb1fl/fl;Aqp2-CreTg double-knockout mice (hereafter referred to as Ift88;Itgb1 DKO mice). In these mice, expression of Cre under the control of the collecting duct-specific aquaporin-2 (Aqp2) promoter is induced at embryonic day 18.5 (25). Despite embryonal activation of Aqp2-Cre, cilia were still visible in the collecting duct epithelial cells of 3-wk-old mice but were absent in 6-mo-old Ift88 KO and Ift88;Itgb1 DKO mice (data not shown). Consistently with the late ablation of the cilium after the critical postnatal switch period (9), Ift88 KO mice showed no remarkable cystogenesis up to 6 mo of age, but a cystic phenotype became overt in most mice by 9 mo (Fig. 1A). At this time, in some of the animals, the kidneys appeared unaffected, indicating the incomplete penetrance of the Ift88 deletion in this last segment of the nephron. Furthermore, female mice were generally less susceptible than male mice to the cystic development (Fig. 1B). Importantly, however, Itgb1 KO animals showed no cystic phenotype, as previously observed (15, 31), and concomitant deletion of integrin-β1 significantly reverted the cystogenesis of Ift88-ablated kidneys in all animals independently of sex (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Integrin-β1 (Itgb1 gene) deletion attenuates renal cystogenesis in Ift88 mutants. A: representative images of 9-mo-old wild-type (WT), Itgb1 knockout (KO), Ift88 KO, and Ift88;Itgb1 double-KO (DKO) kidneys stained with periodic acid-Schiff. B: cystic index (left), blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels (middle), and kidney-to-body weight ratio (right) in 9-mo-old male and female WT, Itgb1 KO, Ift88 KO, and Ift88;Itgb1 DKO mice [the number of animals in each group (n) is indicated at the bottom of each graph]. C: whole kidney expression of kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as determined by quantitative RT-PCR. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

The cystic phenotype in Ift88 KO mice was associated with a decrease of renal function, as determined by blood urea nitrogen elevation, and increase of kidney weight, although these parameters seemed not to depend on sex (Fig. 1B). The renal injury markers kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) were upregulated, possibly reflecting alterations in the tissue architecture (Fig. 1C). Cells positive for Ki-67 were significantly increased in Ift88 KO mice compared with control wild-type or Ift88;Itgb1 DKO mice, suggesting increased proliferation in the single ciliary mutant. At the same time, a small number of TUNEL-positive cells could be appreciated in Ift88 KO kidneys that was not significantly reduced in Ift88;Itgb1 DKO kidneys, indicating a low level of apoptosis, which is generally observed in cystic development (Fig. 2A). Other characteristic features associated with cystic kidney disease were evident. In particular, Ift88 KO kidneys presented significant fibrosis and increased inflammatory infiltrate (Figs. 2, B and C, and 3A), as previously described in Ift88 mutants (3).

Fig. 2.

Inactivation of integrin-β1 (Itgb1 gene) reduced fibrosis in Ift88 mutants. A, top row: representative immunofluorescence images of wild-type (WT; n = 3), Itgb1 knockout (KO; n = 3), Ift88 KO (n = 3), and Ift88;Itgb1 double-KO (DKO) kidneys (n = 3) stained with Ki-67 (green), Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA; red), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 50 μm. The graph on the right shows the quantification of Ki-67-positive cells relative to total cell number (5 fields/mouse). A, bottom row: representative TUNEL images of WT (n = 4), Itgb1 KO (n = 4), Ift88 KO (n = 4), and Ift88;Itgb1 DKO (n = 4) kidneys. Scale bar = 50 μm. The graph on the right shows the corresponding quantification of positive cells relative to total cells (5 fields/mouse). B, top row: representative staining for hematoxylin and eosin of WT, Itgb1 KO, Ift88 KO, and Ift88;Itgb1 DKO kidneys showing the abundant infiltrate. B, middle row: sirius red staining with relative quantification of the positive area from whole kidney sections from WT (n = 2), Itgb1 KO (n = 4), Ift88 KO (n = 6), and Ift88;Itgb1 DKO (n = 5) mice (5 fields/mouse). B, bottom row: representative immunofluorescence images of WT (n = 2), Itgb1 KO (n = 3), Ift88 KO (n = 3), and Ift88;Itgb1 DKO (n = 2) kidneys stained with α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; red) and DBA (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 50 μm. The graph on the right shows relative fluorescence intensity measurements (5 fields/mouse). C: whole kidney expression of fibronectin, collagen type I, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (Timp1) mRNAs as determined. All kidneys were from 9-mo-old animals. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P = 0.0001; ****P < 0.0001.

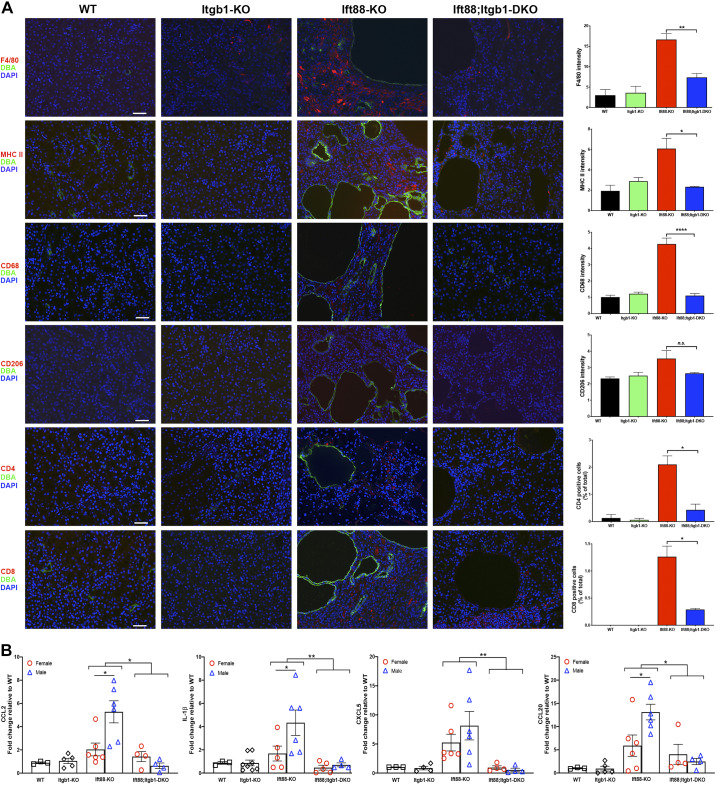

Fig. 3.

Inactivation of integrin-β1 (Itgb1 gene) reduces the inflammation in the kidneys of Ift88 mutants. A: representative immunofluorescence images of wild-type (WT), Itgb1 knockout (KO), Ift88 KO, and Ift88;Itgb1 double-KO (DKO) kidneys costained for Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA; green) and F4/80 (red, first row), major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II; red, second row), CD68 (red, third row), CD206 (red, fourth row), CD4 (red, fifth row), or CD8 (red, sixth row) and then counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 50 μm. The graphs on the right show the corresponding fluorescence intensities determined from n = 2–5/group (5 fields/mouse). B: whole kidney expression of chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL)2, IL1-β, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL)5, and CCL20 mRNAs as determined by quantitative RT-PCR. All kidneys were from 9-mo-old animals. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

To investigate the effects of Itgb1 inactivation on fibrosis in Ift88 KO kidneys, we measured collagen type I deposition and α-SMA expression. Sirius red staining of collagen type I indicated that the degree of fibrosis observed in Ift88 KO kidneys was significantly reduced when integrin-β1 was codeleted (6.1% vs 2.8%; Fig. 2B). Costaining for α-SMA and collecting duct epithelium-specific Dolichos bifluoros agglutinin showed an increased expression of myofibroblasts in Ift88 KO kidneys, particularly in the area around cysts, that was absent in the kidneys of Ift88;Itgb1 DKO mice (Fig. 2B). Correspondingly, expression of fibrotic genes, collagen type I and fibronectin, as well as tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (Timp1) was significantly elevated in Ift88 KO kidneys but near control levels in Ift88;Itgb1 DKO kidneys, confirming the extensive extracellular matrix alterations in the absence of Ift88 (Fig. 2C). While expression of fibronectin and collagen type I was comparable in male and female Ift88 KO mice, the increase in Timp1 expression was driven entirely by the response of male Ift88-KO mice, further underlining sex as a biological variable in the response to the loss of cilia. Overall, these observations suggest that integrin-β1 is required for the fibrotic response in Ift88 KO kidneys. To confirm the inflammatory origin of fibrosis, we determined the nature of the infiltrate, which was characterized by CD4-positive and CD8-positive lymphocytes as well as a substantial macrophage population, as determined by F4/80 staining, both in the interstitium and around the cysts of Ift88 KO kidneys but not in Ift88;Itgb1 DKO kidneys (Fig. 3A). The strong MHC II and CD68 stains and weak CD206 stains suggested the prevalence of the M1 macrophage population, in agreement with the activation of myofibroblasts (Fig. 3A) (6). Consistent with the increased inflammatory macrophage presence and fibrosis, expression of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL)2 as well as chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 and CCL20 was increased in Ift88 KO kidneys but normalized in Ift88;Itgb1 DKO kidneys (Fig. 3B). Of note, expression of CCL2, IL-1β, and CCL20 appeared significantly higher in male than female Ift88 KO mice, suggesting a correlation with the cystic phenotype and a sex-dependent contribution of the immune response in the disease.

DISCUSSION

We showed that the renal cystic phenotype caused by the conditional ablation of Ift88 in the collecting ducts can be prevented by the codeletion of Itgb1. Differently from the lethal Ift88 embryonal systemic deletion (9) or the Ift88 hypomorphic ORPK model, which presents with cystic kidneys at birth and dies within the first weeks after birth (29), the late gestation inactivation of Ift88 in principal cells of the renal collecting ducts produces a slow progressing renal cystic disease characterized by a significant fibrosis and immune infiltrate.

The indolent progression in the Aqp2;Cre-dependent model is likely be due to residual ciliary function that persists up to 3 wk, beyond the time-sensitive phase of susceptibility to cystic development, in agreement with the delayed phenotype observed upon systemic cilia depletion in adult mice (9). In fact, some cilia were detectable in Ift88 KO kidneys at 3 wk of age, although their function cannot be ascertained. Alternatively, it may depend on the deletion of Ift88 limited to the terminal segment of the nephron.

The less severe expression of the cystic phenotype in cilia-deficient female mice supports similar observations by Zimmerman et al. (32) in response to ischemia-reperfusion kidney injury. These differences were paralleled by the lower expression of CCL2, IL-1β, CCL20, and Timp1 in female Ift88 KO kidneys. Overall, these findings are intriguing and point to other physiological regulators of disease progression beyond the scope of this study. It will be important to determine whether this sex difference is observed in other ciliopathies. In particular, sex as a biological variable in the immune response triggered during the cystic process warrants further investigation.

Apoptosis has been observed in polycystic kidney disease and different ciliopathy models as well as in Ift88-depleted organs (2, 7). However, while proliferation and fibrosis increased in Ift88-depleted cystic kidneys, apoptosis was very low and did not significantly change in Ift88;Itgb1 DKO kidneys, suggesting that rather than a pathogenetic driver it may be a secondary event whose frequency may increase at later stages of disease.

As previously reported, an immune infiltrate was present prevalently around the cystic areas (3). Macrophages appeared to be abundantly represented in the infiltrate, concordantly with increased expression of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and CCL2 in Ift88 KO kidneys. While their presence may contribute to the cystogenesis as shown in different genetic models, the lack of both cellular infiltrate and CCL2 expression at earlier times (6 mo) despite the sporadic presence of renal cysts (data not shown) would indicate that the inflammatory components support the progression rather than the onset of cystogenesis. Interestingly, all these pathological changes were absent in Ift88;Itgb1 DKO mice, suggesting a role of integrin-β1 in signaling for immune cells recruitment/development and fibrosis and overall supporting the early involvement of integrin-β1 in the cilia-dependent cystogenetic process.

Since the evidence that Pkd1 may be involved in the repression of a cilium-dependent cyst-promoting pathway, its possible signaling effectors remain unclear. More recently, the causative role for Hedgehog signaling, a classical cilium-dependent regulatory pathway, in the cystogenesis produced by Pkd1 mutation has been ruled out (17). The present findings expand our previous observations on the requirement of integrin-β1 in the cystogenesis caused by the deletion of Pkd1 (15) and place integrin-β1 downstream of the cilium-dependent cyst-promoting pathway, thus suggesting that an integrin-β1-dependent mechanisms may underlie a key cystogenetic signal common to multiple cystic genes. How integrin-β1 may support the cystic signal is still under investigation. However, the function of integrins as cross-linkers of extracellular matrix components and intercellular adhesion molecules with actin microfilaments (11, 12) points to the alteration of mechanical forces as possible triggers of cystic development. Extracellular matrix dysregulation is not only a hallmark manifestation of polycystic kidney disease but has also been shown to contribute to the disease. Lamin-α5 hypomorphs manifest a renal cystic phenotype (26), while the ablation of periostin, a ligand of integrin-αv/β3 and integrin-αv/β5, ameliorates the progression of disease in an orthologous nephronophthisis model (28). Recently, Nigro et al. (20) showed that Pkd1 may coordinate cellular contractility in response to changes in substrate rigidity through the regulation of myosin light chain phosphorylation. Pkd1 has also been shown to control microtubule elongation and stabilization required for normal cell migration (8). Interestingly, the microtubule cytoskeleton is affected in ciliary mutants (4, 5) where acetylated tubulin significantly accumulates in the cytosolic microtubules due to an increased activity of the tubulin acetyltransferase MEC17 (4).

As cross-talk exists between microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton (13), it is plausible that cystic ciliary signals also propagate through changes in microtubule dynamics. Integrin-β1 is not only expressed in the cilium, where it participates in ciliary mechanosensorial functions (22, 23), but is also present in cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix contacts, where it colocalizes with Pkd1 (14) and where the microtubule and actomyosin networks come together (27). As such, integrin-β1 may be the common denominator presiding to the cytoskeletal rearrangements that support both the cilium and Pkd1-dependent cystic processes, and integrin signaling may be an effective target for disease treatment.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01-DK-106035 (to G. L. Gusella) and R01-DK-117913 (to K. Lee). Microscopy was performed at the Microscopy CoRE at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, supported in part with funding from NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant S10-OD-021838.

DISCLOSURES

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.Y., K.L., and G.L.G. conceived and designed research; M.Y. performed experiments; M.Y., L.M.C.B., K.L., and G.L.G. analyzed data; M.Y., K.L., and G.L.G. interpreted results of experiments; M.Y. and G.L.G. prepared figures; M.Y. and G.L.G. drafted manuscript; M.Y., K.L., and G.L.G. edited and revised manuscript; M.Y., L.M.C.B., K.L., and G.L.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anvarian Z, Mykytyn K, Mukhopadhyay S, Pedersen LB, Christensen ST. Cellular signalling by primary cilia in development, organ function and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 15: 199–219, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0116-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attanasio M, Uhlenhaut NH, Sousa VH, O’Toole JF, Otto E, Anlag K, Klugmann C, Treier A-C, Helou J, Sayer JA, Seelow D, Nürnberg G, Becker C, Chudley AE, Nürnberg P, Hildebrandt F, Treier M. Loss of GLIS2 causes nephronophthisis in humans and mice by increased apoptosis and fibrosis. Nat Genet 39: 1018–1024, 2007. doi: 10.1038/ng2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell PD, Fitzgibbon W, Sas K, Stenbit AE, Amria M, Houston A, Reichert R, Gilley S, Siegal GP, Bissler J, Bilgen M, Chou PC-T, Guay-Woodford L, Yoder B, Haycraft CJ, Siroky B. Loss of primary cilia upregulates renal hypertrophic signaling and promotes cystogenesis. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 839–848, 2011. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berbari NF, Sharma N, Malarkey EB, Pieczynski JN, Boddu R, Gaertig J, Guay-Woodford L, Yoder BK. Microtubule modifications and stability are altered by cilia perturbation and in cystic kidney disease. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 70: 24–31, 2013. doi: 10.1002/cm.21088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blitzer AL, Panagis L, Gusella GL, Danias J, Mlodzik M, Iomini C. Primary cilia dynamics instruct tissue patterning and repair of corneal endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 2819–2824, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016702108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braga TT, Agudelo JSH, Camara NOS. Macrophages during the fibrotic process: M2 as friend and foe. Front Immunol 6: 602, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cano DA, Murcia NS, Pazour GJ, Hebrok M. Orpk mouse model of polycystic kidney disease reveals essential role of primary cilia in pancreatic tissue organization. Development 131: 3457–3467, 2004. doi: 10.1242/dev.01189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castelli M, De Pascalis C, Distefano G, Ducano N, Oldani A, Lanzetti L, Boletta A. Regulation of the microtubular cytoskeleton by polycystin-1 favors focal adhesions turnover to modulate cell adhesion and migration. BMC Cell Biol 16: 15, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s12860-015-0059-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davenport JR, Watts AJ, Roper VC, Croyle MJ, van Groen T, Wyss JM, Nagy TR, Kesterson RA, Yoder BK. Disruption of intraflagellar transport in adult mice leads to obesity and slow-onset cystic kidney disease. Curr Biol 17: 1586–1594, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haycraft CJ, Zhang Q, Song B, Jackson WS, Detloff PJ, Serra R, Yoder BK. Intraflagellar transport is essential for endochondral bone formation. Development 134: 307–316, 2007. doi: 10.1242/dev.02732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Humphries JD, Chastney MR, Askari JA, Humphries MJ. Signal transduction via integrin adhesion complexes. Curr Opin Cell Biol 56: 14–21, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadry YA, Calderwood DA. Chapter 22: Structural and signaling functions of integrins. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1862: 183206, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2020.183206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaFlamme SE, Mathew-Steiner S, Singh N, Colello-Borges D, Nieves B. Integrin and microtubule crosstalk in the regulation of cellular processes. Cell Mol Life Sci 75: 4177–4185, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00018-018-2913-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee K, Battini L, Gusella GL. Cilium, centrosome and cell cycle regulation in polycystic kidney disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812: 1263–1271, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee K, Boctor S, Barisoni LMC, Gusella GL. Inactivation of integrin-β1 prevents the development of polycystic kidney disease after the loss of polycystin-1. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2014. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013111179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma M, Gallagher AR, Somlo S. Ciliary mechanisms of cyst formation in polycystic kidney disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 9: a028209, 2017. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma M, Legué E, Tian X, Somlo S, Liem KF Jr. Cell-autonomous Hedgehog signaling is not required for cyst formation in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 2103–2111, 2019. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018121274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma M, Tian X, Igarashi P, Pazour GJ, Somlo S. Loss of cilia suppresses cyst growth in genetic models of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Genet 45: 1004–1012, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ng.2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson RD, Stricklett P, Gustafson C, Stevens A, Ausiello D, Brown D, Kohan DE. Expression of an AQP2 Cre recombinase transgene in kidney and male reproductive system of transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 275: C216–C226, 1998. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.1.C216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nigro EA, Distefano G, Chiaravalli M, Matafora V, Castelli M, Pesenti Gritti A, Bachi A, Boletta A. Polycystin-1 regulates actomyosin contraction and the cellular response to extracellular stiffness. Sci Rep 9: 16640, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53061-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pazour GJ, San Agustin JT, Follit JA, Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB. Polycystin-2 localizes to kidney cilia and the ciliary level is elevated in orpk mice with polycystic kidney disease. Curr Biol 12: R378–R380, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00877-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Praetorius HA, Praetorius J, Nielsen S, Frokiaer J, Spring KR. β1-integrins in the primary cilium of MDCK cells potentiate fibronectin-induced Ca2+ signaling. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F969–F978, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00096.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Praetorius HA, Spring KR. The renal cell primary cilium functions as a flow sensor. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 12: 517–520, 2003. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200309000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raghavan S, Bauer C, Mundschau G, Li Q, Fuchs E. Conditional ablation of beta1 integrin in skin. Severe defects in epidermal proliferation, basement membrane formation, and hair follicle invagination. J Cell Biol 150: 1149–1160, 2000. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raphael KL, Strait KA, Stricklett PK, Miller RL, Nelson RD, Piontek KB, Germino GG, Kohan DE. Inactivation of Pkd1 in principal cells causes a more severe cystic kidney disease than in intercalated cells. Kidney Int 75: 626–633, 2009. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shannon MB, Patton BL, Harvey SJ, Miner JH. A hypomorphic mutation in the mouse laminin α5 gene causes polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1913–1922, 2006. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Small JV, Geiger B, Kaverina I, Bershadsky A. How do microtubules guide migrating cells? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 957–964, 2002. doi: 10.1038/nrm971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallace DP, Quante MT, Reif GA, Nivens E, Ahmed F, Hempson SJ, Blanco G, Yamaguchi T. Periostin induces proliferation of human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney cells through alphaV-integrin receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1463–F1471, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90266.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoder BK, Richards WG, Sommardahl C, Sweeney WE, Michaud EJ, Wilkinson JE, Avner ED, Woychik RP. Differential rescue of the renal and hepatic disease in an autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease mouse mutant. A new model to study the liver lesion. Am J Pathol 150: 2231–2241, 1997. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoder BK, Tousson A, Millican L, Wu JH, Bugg CE Jr, Schafer JA, Balkovetz DF. Polaris, a protein disrupted in orpk mutant mice, is required for assembly of renal cilium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F541–F552, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00273.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X, Mernaugh G, Yang D-H, Gewin L, Srichai MB, Harris RC, Iturregui JM, Nelson RD, Kohan DE, Abrahamson D, Fässler R, Yurchenco P, Pozzi A, Zent R. β1 integrin is necessary for ureteric bud branching morphogenesis and maintenance of collecting duct structural integrity. Development 136: 3357–3366, 2009. doi: 10.1242/dev.036269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerman KA, Song CJ, Li Z, Lever JM, Crossman DK, Rains A, Aloria EJ, Gonzalez NM, Bassler JR, Zhou J, Crowley MR, Revell DZ, Yan Z, Shan D, Benveniste EN, George JF, Mrug M, Yoder BK. Tissue-resident macrophages promote renal cystic disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 1841−1856, 2019. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018080810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]