Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy before ureteroscopy in the management of ureteral stones.

Methods

The databases MEDLINE®, EMBASE and The Cochrane Controlled Trail Register of Controlled Trials were searched between January 1980 and June 2019 to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that referred to the use of alpha-blockers as adjunctive therapy before ureteroscopy for the treatment of ureteral stones. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used for dichotomous outcomes; and mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs were used to report continuous outcomes.

Results

The analysis included five RCTs with a total of 557 patients. Compared with placebo, patients that received adjunctive alpha-blockers had significantly higher successful access to the stone (OR 5.44; 95% CI 2.99, 9.88), a significantly higher stone-free rate at the end of week 4 (OR 3.75; 95% CI 2.20, 6.39), significantly less requirement for balloon dilatation (OR 0.26; 95% CI 0.15, 0.44) and a significantly lower risk of complications (OR 0.25; 95% CI 0.15, 0.42). There was no significant difference in the operation time between the two groups (MD –3.33; 95% CI –7.03, 0.37).

Conclusions

Adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy administered before ureteroscopy was effective in the management of ureteral stones with a lower risk of complications than placebo treatment.

Keywords: Alpha-blockers, ureteroscopy, ureteral stones, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trials

Introduction

Urolithiasis is a major health problem worldwide with increasing incidence and prevalence, which is attributed primarily to the increase in type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity and metabolic syndrome.1–4 The management of urethral stones consists of observation, medical expulsive therapy (MET), shockwave lithotripsy (SWL), ureteroscopy, percutaneous nephrolithotomy or open and laparoscopic stone surgery, depending on the clinical situation.5

The selective alpha-blockers are widely used in the clinical treatment for ureteral stones as MET. For example, previously published meta-analyses, as well as the American Urological Association and European Association of Urology, strongly recommend that patients with ureteral stones be offered alpha-blockers to promote stone passage.6,7 The most recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses demonstrate the benefit of alpha-blockers for the treatment of larger stones in the ureter.8,9 The presumed mechanism of action of alpha-blockers is the inhibition of smooth muscle contraction in the ureter, causing relaxation of the ureter smooth muscle and reducing the strength and frequency of peristalsis.10

In 1980, the first use of rigid retrograde ureteroscopy was reported.11 Thanks to technical improvements and the introduction of a wide range of disposables, rigid or flexible uretero(reno)scopes can be used for the whole ureter, depending on individual anatomy and surgeon preference.6 Ureteroscopy has become the standard treatment method for ureteral stones, with a high success rate.12 However, advancing an ureteroscope into the non-dilated ureter is difficult and carries the risk of inevitable complications, which may lead to the failure of the procedure.13

Due to the physiological effect of alpha-blockers on the ureter, researchers hypothesized that the use of alpha-blockers before ureteroscopy may help during the ureteroscopic procedures, making it easier and safer. A previous study reported that tamsulosin therapy prior to semi-rigid ureteroscopy improved ureteroscopic access to proximal ureteral stones.13 Subsequent publications demonstrated that alpha-blockers (tamsulosin and silodosin) increased access to stones and contributed to stone-free rates.13–17 To date, there has not been a systematic meta-analysis to assess the efficacy and safety of adjunctive alpha-blockers versus placebo before ureteroscopy in the treatment of ureteral stones. Therefore, this current meta-analysis evaluated the effects of adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy prior to ureteroscopy in patients with ureteral stones.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Electronic databases, including MEDLINE®, EMBASE and The Cochrane Controlled Trail Register of Controlled Trials, were searched between January 1980 and June 2019 using the following search terms: alpha-blockers, silodosin, tamsulosin, ureteroscopy, ureteral calculi, ureteral stones and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Abbreviations (α-blockers, ureteroscopy [URS], RCT) were also searched. The reference lists of the retrieved publications were examined to identify other potentially eligible RCTs that referred to the efficacy and safety of adjunctive alpha-blockers therapy before ureteroscopy for the treatment of ureteral stones.

Inclusion criteria

The RCTs were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: (i) studied the efficacy and safety of adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy before ureteroscopy for the treatment of ureteral stones; (ii) provided sufficient data for analysis, including successful access to stone, stone-free rate at the end of week 4, patients that needed balloon dilatation, operation time and complications; (iii) the full text of the study could be accessed. If the above inclusion criteria were not met, the studies were excluded from the analysis.

Trial selection

All four authors independently identified potentially relevant studies and trials. Together, the four authors discussed each of the RCTs that were included and excluded. Studies that either failed to meet the inclusion criteria or had discrepancies that could not be resolved were excluded.

Data extraction

The four authors independently performed the data extraction for the meta-analysis, which included the following: (i) the name of the first author and the publication year; (ii) the design of the study; (iii) the therapy that the patients received; (iv) the location of the ureteral stones; (v) the size and type of ureteroscope used; (vi) the number of patients; (vii) the duration of adjunctive alpha-blocker treatment; (viii) the outcome measures of the study.

Quality assessment

All of the identified RCTs were included in the meta-analysis regardless of the quality score. The quality of the RCTs was assessed in terms of sequence generation, the concealment of allocation procedures, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias. The studies were then classified qualitatively according to the guidelines published in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions v.5.1.0.18 Based on the quality assessment criteria, each study was rated and assigned to one of the following three quality categories: A, low risk of bias; B , unclear risk of bias; C, high risk of bias. Differences were resolved by discussion among the four authors.

Statistical analyses

Regarding the dichotomous outcomes, odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used where available. Mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs were used to report continuous outcomes. The comparative effects were initially analysed using the traditional pairwise meta-analysis method using Cochrane Collaboration RevMan software (version 5.1.0; Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). The OR for dichotomous outcomes and the MD for continuous outcomes pooled across the studies were estimated using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model.19 A ‘fixed-effects’ statistical model was used if there was no conspicuous heterogeneity. A ‘random-effects’ model was used if heterogeneity was detected. The tests for heterogeneity were performed using χ2-test with the significance level set at P < 0.1. A sensitivity analysis was performed to determine whether the heterogeneity was a result of low study quality.

Results

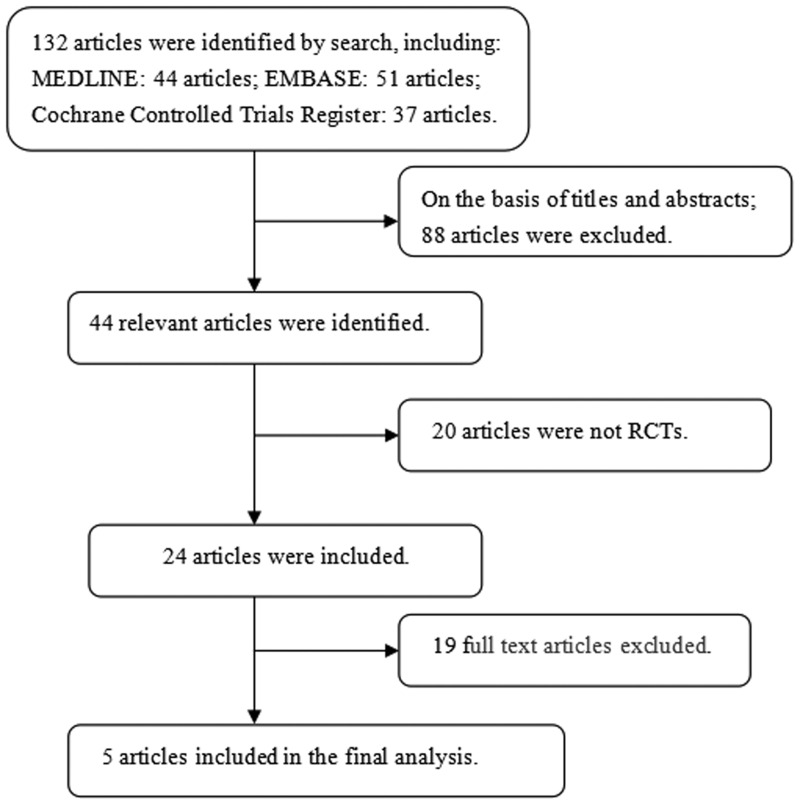

A flow chart showing the study selection process is presented in Figure 1. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, five RCTs involving 557 patients (274 in the alpha-blockers group and 283 in the placebo group) were included in the analysis.13–17 The characteristics of the individual studies are presented in Table 1. All five studies included in the meta-analysis were RCTs. The risk of bias of the five studies was generally low (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of eligible studies showing the number of citations identified, retrieved and included in the final meta-analysis.

Table 1.

The characteristics of the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that were included in the present meta-analysis to evaluate the effects of adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy prior to ureteroscopy in patients with ureteral stones.13–17

| Author | Year | Study design |

Therapy |

Location of ureteral calculus | Size of ureteroscope | Type of ureteroscope |

Sample size |

Duration of treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Experiment | Control | Experiment | |||||||

| Bayar et al.17 | 2019 | RCT | Diclofenac 50 mg | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg +diclofenac 50 mg | Ureter | 6/7.5 Fr | Semi-rigid | 63 | 61 | 7 days |

| Mohey et al.16 | 2018 | RCT | Placebo (multivitamins) | Silodosin 8 mg | Distal ureter | 8/9.5 Fr | Semi-rigid | 65 | 62 | 10 days |

| Aydin et al.14 | 2018 | RCT | Diclofenac 50 mg | Silodosin 8 mg +diclofenac 50 mg | Ureter | 7/7.5 Fr | Semi-rigid | 50 | 47 | 3 days |

| Bhattar et al.15 | 2017 | RCT | Placebo (multivitamins) | Silodosin 8 mg | Ureter | 8/9.8 Fr | Not mentioned | 21 | 23 | 14 days |

| Ahmed et al.13 | 2017 | RCT | Placebo | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg | Proximal ureter | 7.5 Fr | Semi-rigid | 84 | 81 | 7 days |

Fr, French.

Table 2.

The risk of bias for the randomized controlled trials that were included in the present meta-analysis to evaluate the effects of adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy prior to ureteroscopy in patients with ureteral stones.13–17

| Author | Year | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | Other sources of bias | Level of quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayar et al.17 | 2019 | A | A | A | B | A | A | A |

| Mohey et al.16 | 2018 | A | A | A | B | A | A | A |

| Aydin et al.14 | 2018 | A | A | A | B | B | A | B |

| Bhattar et al.15 | 2017 | A | A | A | B | A | A | A |

| Ahmed et al.13 | 2017 | A | A | A | B | A | A | A |

A, low risk of bias; B, unclear risk of bias; C, high risk of bias.

All five studies (n = 557; 274 in the alpha-blockers group and 283 in the placebo group) contributed to the analysis of the successful access to the stones.13–17 No heterogeneity was found among the trials so a fixed-effects model was chosen for the analysis. Compared with the placebo group, the adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy was associated with a significantly higher rate of successful access to the stones (OR 5.44; 95% CI 2.99, 9.88; P < 0.00001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Successful access to the ureteral stone during ureteroscopy in groups treated with either adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy or placebo therapy before ureteroscopy.13–17

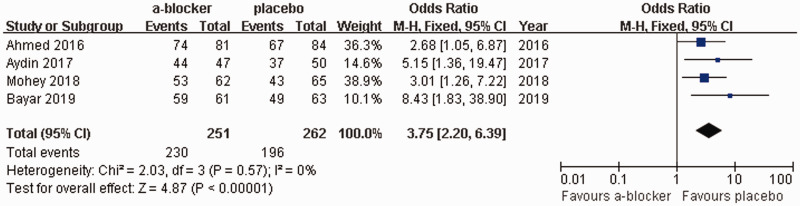

Four studies (n = 513; 251 in the alpha-blockers group and 262 in the placebo group) contributed to the analysis of the stone-free rate at the end of week 4.13,14,16,17 No heterogeneity was found among the trials so a fixed-effects model was chosen for the analysis. Compared with the placebo group, the adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy was associated with a significantly higher successful stone-free rate at the end of week 4 (OR 3.75; 95% CI 2.20, 6.39; P < 0.00001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Stone-free rate at the end of week 4 in groups treated with either adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy or placebo therapy before ureteroscopy.13,14,16,17

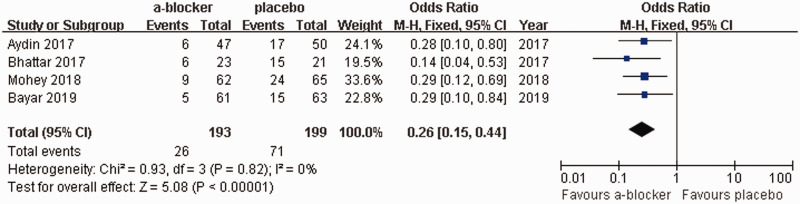

A total of four studies (n = 392 patients; 193 in the alpha-blockers group and 199 in the placebo group) contributed to the analysis of the number of patients that needed balloon dilatation.14–17 No heterogeneity was found among the trials, so a fixed-effects model was chosen for the analysis. Compared with the placebo group, the adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy was associated with a significantly lower need for balloon dilatation during ureteroscopy (OR 0.26; 95% CI 0.15, 0.44; P < 0.00001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Requirement for balloon dilatation during ureteroscopy in groups treated with either adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy or placebo therapy before ureteroscopy.14–17

All five studies (n = 557; 274 in the alpha-blockers group and 283 in the placebo group) were used in the analysis of operation time.13–17 Heterogeneity was found among the trials (I2 = 82%; P = 0.0002), so a random-effects model was chosen for the analysis. There was no significant difference in operation time between the adjunctive alpha-blockers and placebo groups (MD: –3.33; 95% CI –7.03, 0.37; P = 0.08) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Analysis of the operation time (min) in groups treated with either adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy or placebo therapy before ureteroscopy.13–17

Perforation, formation of a false lumen and mucosal haemorrhage requiring the operation to end were defined as complications. All five studies (n = 557; 274 in the alpha-blockers group and 283 in the placebo group) contributed to the analysis of complications.13–17 No heterogeneity was found among the trials, so a fixed-effects model was chosen for the analysis. Compared with the placebo group, the adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy was associated with a significantly lower incidence of complications (OR 0.25; 95% CI 0.15, 0.42; P < 0.00001) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Analysis of the complications in groups treated with either adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy or placebo therapy before ureteroscopy.13–17

Discussion

Ureteral calculi account for 20% of urinary tract stones and affect 5–10% of the population.20,21 Most professional societies recognize the off-label use of alpha-blockers as an initial treatment option for patients with ureteric stones < 10 mm in size as MET.6,7 In addition, alpha-blockers are known to significantly increase the spontaneous passage of stone fragments in the ureter after SWL and ureteroscopy.22,23 The ureteroscope has facilitated the diagnosis and treatment of various urological diseases, especially ureteral stones.24 Although ureteroscopy has yielded high success rates in the treatment of ureteral stones, the surgical procedure is technically difficult. Various techniques have been used to achieve dilatation, such as passive dilatation (using a double J stent) or active dilatation (using balloons, sequential fascial dilator), with the purpose of overcoming the difficult negotiation of the ureter, but these techniques may carry the risk of complications.25,26 Several RCTs have reported the promising results of adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy before ureteroscopy.13–17

A previous RCT that included 1136 analysed patients reported that tamsulosin was not effective in terms of stone-free status at 4-weeks follow-up.27 The current meta-analysis results were different to those of the previous study,27 which suggests that caution is required when considering the results of the current meta-analysis of five relatively small RCTs.13–17 A network meta-analysis showed a significant increase in stone expulsion rate and a reduction in stone expulsion time with alpha-blockers compared with placebo or phosphodiesterase inhibitors.28 In terms of the stone expulsion rate, alpha-blockers were very likely to be the ‘best’ interventions.28 Several meta-analyses have indicated that alpha-blockers are effective following SWL for stone clearance and for relieving patient discomfort following ureteric stent placement.29,30 To date, the utility of alpha-blocker use prior to routine ureteroscopy for ureteral stones remains unclear and controversial. This current meta-analysis demonstrated that adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy before ureteroscopy significantly improved successful access to the stones, the stone-free rate at the end of week 4 and reduced the need for balloon dilatation. In addition, alpha-blocker therapy before ureteroscopy significantly decreased the complication rate compared with placebo, though the operation time was similar between the two groups. Therefore, this current meta-analysis provides evidence that preoperative alpha-blockers are an effective therapy for patients undergoing ureteroscopy for ureteral stones.

It is noteworthy that this current meta-analysis demonstrated that there was no significant difference in operation time between the adjunctive alpha-blocker and placebo groups. As is well known, the operative time of ureteroscopy is greatly affected by the surgeons’ experience, the time needed to achieve ureteral access and the stone size and density that affect the laser firing time, active fragment retrieval and use and type of post-ureteroscopy stents. These factors might have affected the current results.

The α-adrenergic receptors are classified into three different subtypes: α1A, α1B and α1D.31 The human ureter contains α1-adrenergic receptors along its entire length, particularly the subtypes α1A and α1D, which are more densely located in the distal ureter and ureterovesical junction as compared with the proximal and middle ureter.32 The role of adrenergic receptors in the human ureter was first described in 1970.33 It was shown that stimulation of α1-adrenergic receptors enhanced ureteral contraction and increased ureteral peristalsis.34 Thus, selective α1A/α1D-adrenergic receptor antagonists, such as tamsulosin and silodosin, should induce relaxation of the ureteric smooth muscles and dilatation of the ureteric lumen. Therefore, the ureteroscope may advance more easily, providing increased access to stones and a decreased complication rate.13

In the current meta-analysis, perforation, formation of a false lumen and mucosal haemorrhage requiring the operation to end were defined as complications and the adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy was associated with a significantly lower rate of complications compared with the placebo group (P < 0.00001), suggesting that the adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy resulted in safer ureteroscopic procedures.

This study had several limitations despite the fact that all five RCTs included in this current meta-analysis had a low risk of bias and their quality was high. First, because of the limited quantity of relevant original studies, this meta-analysis only included five studies with sample sizes that were not large. Secondly, the duration of treatment with adjunctive alpha-blockers prior to ureteroscopy ranged from 3 days to 2 weeks. Thirdly, the size of the ureteroscope was not consistent across the studies, ranging from 6 Fr to 9.8 Fr. In addition, the lack of uniform inclusion criteria, the variation in the types of alpha-blockers used, the different types of ureteroscope used and the different locations of the ureteral stones may have resulted in bias. In addition, other endpoints (preoperative and postoperative J stent placement rates, SWL histories and the use of the alpha-blocker treatment after the ureteroscopy) were lacking because the data were too scarce to be formally analysed. After the heterogeneity among individual studies was taken into account, this meta-analysis provides valuable data on the efficacy and safety of adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy versus placebo before ureteroscopy for the treatment of ureteral stones. Further high-quality RCTs are required to provide more information on the use of adjunctive alpha-blockers before ureteroscopy for the treatment of ureteral stones.

In conclusion, this current meta-analysis demonstrated that adjunctive alpha-blocker therapy before ureteroscopy was effective and safe in the management of ureteral stones.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Trinchieri A, Coppi F, Montanari E, et al. Increase in the prevalence of symptomatic upper urinary tract stones during the last ten years. Eur Urol 2000; 37: 23–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scales CD, Jr, Smith AC, Hanley JM, et al. Urologic Diseases in America Project. Prevalence of kidney stones in the United States. Eur Urol 2012; 62: 160–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antonelli JA, Maalouf NM, Pearle MS, et al. Use of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to calculate the impact of obesity and diabetes on cost and prevalence of urolithiasis in 2030. Eur Urol 2014; 66: 724–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeong IG, Kang T, Bang JK, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and the presence of kidney stones in a screened population. Am J Kidney Dis 2011; 58: 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Türk C, Petřík A, Sarica K, et al. EAU guidelines on interventional treatment for urolithiasis. Eur Urol 2016; 69: 475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preminger GM, Tiselius HG, Assimos DG, et al. 2007 guideline for the management of ureteral calculi. J Urol 2007; 178: 2418–2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assimos D, Krambeck A, Miller NL, et al. Surgical Management of Stones: American Urological Association/Endourological Society Guideline, PART I. J Urol 2016; 196: 1153–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollingsworth JM, Canales BK, Rogers MA, et al. Alpha blockers for treatment of ureteric stones: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2016; 355: i6112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang W, Xue P, Zong H, et al. Efficacy and safety of silodosin in the medical expulsion therapy for distal ureteral calculi: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 81: 13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meltzer AC, Burrows PK, Wolfson AB, et al. Effect of Tamsulosin on Passage of Symptomatic Ureteral Stones: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178: 1051–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pérez-Castro E, Martínez Piñeiro JA. . La ureterorrenoscopia transurethral: un actual proceder urológico. Arch Esp Urol 1980; 33: 445–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yencilek F, Sarica K, Erturhan S, et al. Treatment of ureteral calculi with semirigid ureteroscopy: where should we stop? Urol Int 2010; 84: 260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed A, Maarouf A, Shalaby E, et al. Semi-rigid ureteroscopy for proximal ureteral stones: does adjunctive tamsulosin therapy increase the chance of success. Urol Int 2017; 98: 411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aydin M, Kilinç MF, Yavuz A, et al. Do alpha-1 antagonist medications affect the success of semi-rigid ureteroscopy? A prospective, randomised, single-blind, multicentric study. Urolithiasis 2018; 46: 567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhattar R, Jain V, Tomar V, et al. Safety and efficacy of silodosin and tadalafil in ease of negotiation of large ureteroscope in the management of ureteral stone: a prospective randomized trial. Turk J Urol 2017; 43: 484–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohey A, Gharib TM, Alazaby H, et al. Efficacy of silodosin on the outcome of semi-rigid ureteroscopy for the management of large distal ureteric stones: blinded randomised trial. Arab J Urol 2018; 16: 422–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bayar G, Kilinc MF, Yavuz A, et al. Adjunction of tamsulosin or mirabegron before semi-rigid ureterolithotripsy improves outcomes: prospective, randomized single-blind study. Int Urol Nephrol 2019; 51: 931–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, v.5.1.0 (updated March 2011). Cochrane Collaboration Web site 2011. http: //www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- 19.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7: 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curhan GC. Epidemiology of stone disease. Urol Clin North Am 2007; 34: 287–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ketabchi AA, Aziziolahi GA. Prevalence of symptomatic urinary calculi in Kerman, Iran. Urol J 2008; 5: 156–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuler TD, Shahani R, Honey RJ, et al. Medical expulsive therapy as an adjunct to improve shockwave lithotripsy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endourol 2009; 23: 387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.John TT, Razdan S. Adjunctive tamsulosin improves stone free rate after ureteroscopic lithotripsy of large renal and ureteric calculi: a prospective randomized study. Urology 2010; 75: 1040–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuchs GJ. Milestone in endoscope design for minimally invasive urologic surgery: the sentinel role of a pioneer. Surg Endosc 2006; 20: S493–S499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Hakim A, Tan BJ, Smith AD. Ureteroscopy: technical aspects. Urinary stone disease: the practical guide to medical and surgical management. Humana, Totowa, New Jersey 2007; 589–607. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joshi HB, Newns N, Stainthorpe A, et al. Ureteral stent symptom questionnaire: development and validation of a multidimensional quality of life measure. J Urol 2003; 169: 1060–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pickard R, Starr K, MacLennan G, et al. Medical expulsive therapy in adults with ureteric colic: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386: 341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sridharan K, Sivaramakrishnan G. Medical expulsive therapy in urolithiasis: a mixed treatment comparison network meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2017; 18: 1421–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu Y, Duijvesz D, Rovers MM, et al. Alpha-blockers to assist stone clearance after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy: a meta-analysis. BJU Int 2010; 106: 256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamb AD, Vowler SL, Johnston R, et al. Meta-analysis showing the beneficial effect of α-blockers on ureteric stent discomfort. BJU Int 2011; 108: 1894–1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itoh Y, Kojima Y, Yasui T, et al. Examination of alpha 1 adrenoceptor subtypes in the human ureter. Int J Urol 2007; 14: 749–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasaki S, Tomiyama Y, Kobayashi S, et al. Characterization of α1-adrenoceptor subtypes mediating contraction in human isolated ureters. Urology 2011; 77: e13–e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malin JM, Jr, Deane RF, Boyarsky S. Characterisation of adrenergic receptors in human ureter. Br J Urol 1970; 42: 171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss RM, Bassett AL, Hoffman BF. Adrenergic innervation of the ureter. Invest Urol 1978; 16: 123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]