Abstract

The failure of standard treatment for patients diagnosed with glioblastoma (GBM) coupled with the highly vascularized nature of this solid tumor has led to the consideration of agents targeting VEGF or VEGFRs, as alternative therapeutic strategies for this disease. Despite modest achievements in survival obtained with such treatments, failure to maintain an enduring survival benefit and more invasive relapsing tumors are evident. Our study suggests a potential mechanism by which anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapies regulate the enhanced invasive phenotype through a pathway that involves TGFβR and CXCR4. VEGFR signaling inhibitors (Cediranib and Vandetanib) elevated the expression of CXCR4 in VEGFR-expressing GBM cell lines and tumors, and enhanced the in vitro migration of these lines toward CXCL12. The combination of VEGFR inhibitor and CXCR4 antagonist provided a greater survival benefit to tumor-bearing animals. The upregulation of CXCR4 by VEGFR inhibitors was dependent on TGFβ/TGFβR, but not HGF/MET, signaling activity, suggesting a mechanism of crosstalk among VEGF/VEGFR, TGFβ/TGFβR, and CXCL12/CXCR4 pathways in the malignant phenotype of recurrent tumors after anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapies. Thus, the combination of VEGFR, CXCR4, and TGFβR inhibitors could provide an alternative strategy to halt GBM progression.

Keywords: CXCR4, TGFβR, VEGFR, MET, Anti-angiogenic therapy, GBM

Introduction

WHO Grade IV glioblastoma (GBM) accounts for 52% of all primary brain tumor cases. Standard of care for GBM includes maximal surgical resection of the tumor, followed by radiation in combination with chemotherapy. However, the median progression-free survival is only 7 months and tumors recur in a large subset of GBM patients [1,2]. The failure of this standard regimen for GBM can be accounted by multiple factors including, but not limited to, the heterogeneity of the microenvironment, de novo and/or acquired tumor resistance, and limitations in drug delivery [3]. To improve the effectiveness of GBM treatment, continued efforts will be needed to identify additional novel therapeutic targets.

Strategies that target angiogenesis have received great attention due to their potential effectiveness in highly vascularized tumors, such as GBM. Tumor angiogenesis is strongly regulated by the VEGF/VEGFR system, of which both ligands and receptors have been found in GBMs [4–6]. Data from clinical trials suggest that, in some patients with recurrent GBM treated with either anti-VEGF antibodies (e.g. Bevacizumab), VEGF binding proteins (e.g. Aflibercept), or small molecular VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g. Cediranib, Vandetanib), these agents could enhance 6-month progression free survival rate (PFS), as well as radio-graphic responses [7–11]. These studies prompted phase III trials evaluating Bevacizumab in combination with chemoradiation in newly diagnosed GBM [12,13]. Under VEGF pathway inhibition with Bevacizumab, a statistically significant increase in infiltrative tumor progression was identified in Bevacizumab responders [14]. The enhanced infiltrative relapse following Bevacizumab was observed when this agent was evaluated as either first- or second-line treatment [15–17]. While evidence suggests that enhanced tumor invasion may be a direct consequence of anti-angiogenic therapy, the underlying mechanism that controls this phenomenon is poorly understood. Recently published results support a role for the HGF/MET in this enhanced invasive phenotype after anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapy [18]. In the presence of anti-VEGF/VEGFR agents, VEGFR2 forms heterodimers with MET, and this interaction causes the dissociation of the protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) from MET, thereby unmasking MET activity and promoting invasion of GBM cells. These data suggest that integrating VEGFR and MET inhibitors will prevent tumor recurrence after anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapy.

In addition to HGF/MET, the invasive phenotype of tumor cells can be regulated by other mechanisms, including the chemokine receptor CXCR4. CXCR4 and its ligand CXCL12 have received considerable attention for their roles in tumor progression that include tumor growth, invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis [19–30]. Their presence in human GBM specimens, as well as tumors from xenograft models is well documented [21,23,31–33]. Studies with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist, showed that CXCR4 blockade could impair GBM growth and invasion [21,23,33].

We report an additional mechanism by which anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapies can regulate the enhanced invasive phenotype through a pathway involving CXCR4. Agents with VEGFR inhibitory activity elevate the expression of CXCR4 in GBM cell lines and xenografts expressing VEGFRs. This upregulation is dependent on TGFβ receptor activity and independent of HGF/MET signaling. Moreover, the combination of Cediranib and AMD3100 provided an enhanced survival benefit to tumor-bearing animals, compared to monotherapies. These data suggest that TGFβ/TGFβR control of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis may contribute to the invasive phenotype of recurrent tumors after anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapy and that the combination of VEGF/VEGFR inhibitors, CXCR4 antagonists, and TGFβR inhibitors may provide a major advantage to halt GBM progression.

Materials and methods

Animals

NOD-scid IL2Rγnull (NSG) mice were from Jackson Laboratories. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell lines and culture conditions

GBM lines L0 (43 yr old male), L1 (45 yr old female), L2 (30 yr old female), SN179 (50 yr old male), and SN186 (75 yr old male) were used in the study; all lines have been extensively published by us [34–41]. Cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 2% B27, 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF), 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), 5 μg/ml of heparin and 1% penicillin–streptomycin and grown in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. DMEM/F12 medium, B27, EGF, bFGF, L-glutamine and antibiotics were obtained from Gibco-BRL (Invitrogen).

Reagents

Cediranib and Vandetanib were provided by Drs. Juliane M. Jürgensmeier and David Blakey (AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals). AMD3100 (Tocris, UK), HGF (Millipore), TGFβ (R&D Systems), and TBRI (Calbiochem) were obtained from the indicated commercial sources. BMS777607 was provided by Dr. Joseph Fargnoli (Bristol-Myers Squibb).

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated with the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen); genomic DNA was removed by RQ1 RNase-free DNase treatment (Promega, WI). RNA (1 μg) was retrotranscribed with iScript complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). cDNA was subjected to PCR analysis by heating for 96 °C for 2 min, followed by amplification for 35 cycles: 96 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 1 min. Touchdown PCR was utilized in some instances; the annealing temperature started at 65 °C and was decreased by 1 °C every cycle for 15 cycles and reached 50 °C; 50 °C was then used for the remaining number of cycles with denaturing and elongating temperatures the same as mentioned previously. All primers, designed to span introns, are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of primers used in RT-PCR.

| Gene | Primer |

|---|---|

| Human VEGF | 5’-gaagtggtgaagttcatggatgtc-3’ (forward) 5’-cgatcgttctgtatcagtctttcc-3’ (reverse) |

| Human VEGFR1 | 5’-gcaccttggttgtggctgac-3’ (forward) 5’-cgtgctgcttcctggtcc-3’ (reverse) |

| Human VEGFR2 | 5’-gtcaagggaaagactacgttgg-3’ (forward) 5’-agcagtccagcatggtctg-3’ (reverse) |

| Human VEGFR3 | 5’-cccacgcagacatcaagacg-3’ (forward) 5’-tgcagaactccacgatcacc-3’ (reverse) |

| Human HGF | 5’-ctcacacccgctgggagtac-3’ (forward) 5’-tccttgaccttggatgcattc-3’ (reverse) |

| Human c-Met | 5’-acagtggcatgtcaacatcgct-3’ (forward) 5’-gctcggtagtctacagattc-3’ (reverse) |

| Human TGFβl | 5’-tggtggaaacccacaacgaa-3’ (forward) 5’- agaagttggcatggtagccc-3’ (reverse) |

| Human TGFβ2 | 5’-tcttcccctccgaaaatgcc-3’ (forward) 5’-aaagtggacgtaggcagcaa-3’(reverse) |

| Human TGFβ3 | 5’-acccaggaaaacaccgagtc-3’ (forward) 5’-atcctcattgtccacgccttt-3’ (reverse) |

| Human TGFβRl | 5’-caaccgcactgtcattcacc-3’ (forward) 5’-cttcaggggccatgtaccttt-3’ (reverse) |

| Human TGFβR2 | 5’-gcacgttcagaagtcggatgt-3’ (forward) 5’-gaggctgatgcctgtcactt-3’ (reverse) |

| Human TGFβR3 | 5’-cggcttgaaaataatgcagagg-3’ (forward) 5’-cacgatttcaggtcgggtga-3’ (reverse) |

| Human actin | 5’-ctcttccagccttccttcct-3’ (forward) 5’-caccttcaccgttccagttt-3’ (reverse) |

Flow cytometry

Gliomaspheres were dissociated with Accumax solution (Innovative Cell Technologies Inc., CA), washed with ice cold PBS and incubated in blocking solution containing 5 μg/ml of mouse and rat IgG in 5% BSA diluted in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were incubated with mouse anti-human CXCR4-APC (dilution 1:10, R&D Systems) or non-immune IgG-APC, for 30 min on ice. Samples were washed and analyzed with the BD LSR II system (BD Biosciences). Dead cells were excluded by DAPI staining. Data were analyzed by FlowJo software version 7.6 (Tree Star). Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Immunocytochemistry

Gliomaspheres were harvested and gently dissociated with diluted cell dissociation solution (Accumax, Innovative Cell Technologies Inc., CA) in PBS (1:500). Cells were then blocked with 2% BSA in PBS for 1 hr, incubated with mouse anti-human CXCR4 antibody (R&D Systems) for 1 hr, and with goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa 488 for 1 hr. Washing steps were performed with PBS (3 times, 5 min each). Cells were counterstained with DAPI, mounted with aqueous mounting solution and photographed with Zeiss fluorescent microscope (40× objective).

Immunohistochemistry

Brain/tumor sections were heated for 30 min at 70 °C, deparaffnized in Xylene (3 × 5 min), and then rehydrated by stepwise immersion in 100% EtOH (2 × 5 min), 95% EtOH (2 × 5 min), and 70% EtOH (1 × 3 min). After deparaffinization, samples were rinsed with deionized water and processed for antigen retrieval with sodium citrate buffer pH 6, or EDTA pH 8 for 15 min at 98 °C. After cooling to room temperature, samples were washed with deionized water (5 min), quenched with 3% H2O2 (10 min) at room temperature to block endogenous peroxidase activity, and processed for staining. Sections were initially blocked with 5% BSA in TBS-T (1 h), incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, and then with secondary antibodies (1 h) at room temperature. Washing steps were performed with TBS-T (3 times, 5 min each). Finally, the sections were counterstained with DAPI. Primary antibodies used were: mouse anti-human Nestin (dilution 1:100, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA), mouse anti-human CXCR4 (dilution 1:50, R&D Systems), rabbit anti-human/mouse VEGFR2 (dilution 1:50, Cell Signaling), and rabbit anti-human/mouse HIF1α (dilution 1:50, Abcam). Secondary antibodies used were: goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa 594, goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa 488 (1:500, Invitrogen), and goat anti-mouse HRP conjugated IgG (1:3000, Perkin Elmer). Sections were visualized/photographed with a Zeiss fluorescent microscope (20× objective).

Migration assay

In vitro migration assays were performed with modified Boyden chambers using 24-well transwell units with 8 μm pore polycarbonated filters (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ). After treatment with either 500 nM of Cediranib or Vandetanib (16 h), cells were dissociated with 0.02% EDTA in PBS, pH 7.4, and 105 cells were resuspended in serum-free medium and transferred to culture inserts (top chamber). The assembly was placed into 24-well plates containing 3 nM CXCL12 (bottom chamber). After 24 hr, migrating cells located at the bottom of the insert were stained with Calcein AM dye (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 37 °C, and analyzed using a fluorescent plate reader for intensity quantification. Cell numbers were determined by comparison to the standard curve for each cell line. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated at least two times using different cell preparations.

Intracranial injection of GBM cells

GBM cells (105 cells/brain) were injected 3 mm deep into the right cerebral hemisphere (1 mm posterior and 2 mm lateral from Bregma) of NSG mice. Tumor-bearing mice were euthanized using sodium pentobarbital (32 mg/kg) and subsequently perfused with 0.9% saline followed by buffered 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Brains were surgically removed and post-fixed with 4% PFA. After fixation, brains were embedded with paraffin, sectioned using a microtome, and subjected to immunohistochemical analysis.

Drug treatments

Cediranib was delivered for four weeks by oral gavage at a dose of 6 mg/kg, once a day, in 10% Tween 80 diluted in PBS, starting 2 weeks after cell implantation. Animals also received AMD3100 treatment alone or in combination with Cediranib injected subcutaneously, at a dose of 5 mg/kg, twice daily in sterile PBS beginning from the 4th week after cell implantation, and continuing for 2 weeks. A control group of mice was treated with vehicle only. The number of mice used in each treated group is indicated on the survival curve.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis

Percentages of surviving mice (Kaplan–Meier survival analysis) in each group of animals were recorded daily after GBM cell implantation. The endpoint was defined by a lack of physical activity and a body weight reduction >15%. The data were subjected to Log-rank analysis to determine if significant differences existed in survival between the experimental groups.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Data are presented as mean and standard error of mean. P-values were calculated using Student’s t-test with one-tailed distribution. Survival data were subjected to log-rank test. A P-value <0.05 was considered significant and is indicated by symbols in the figures and legends.

Results

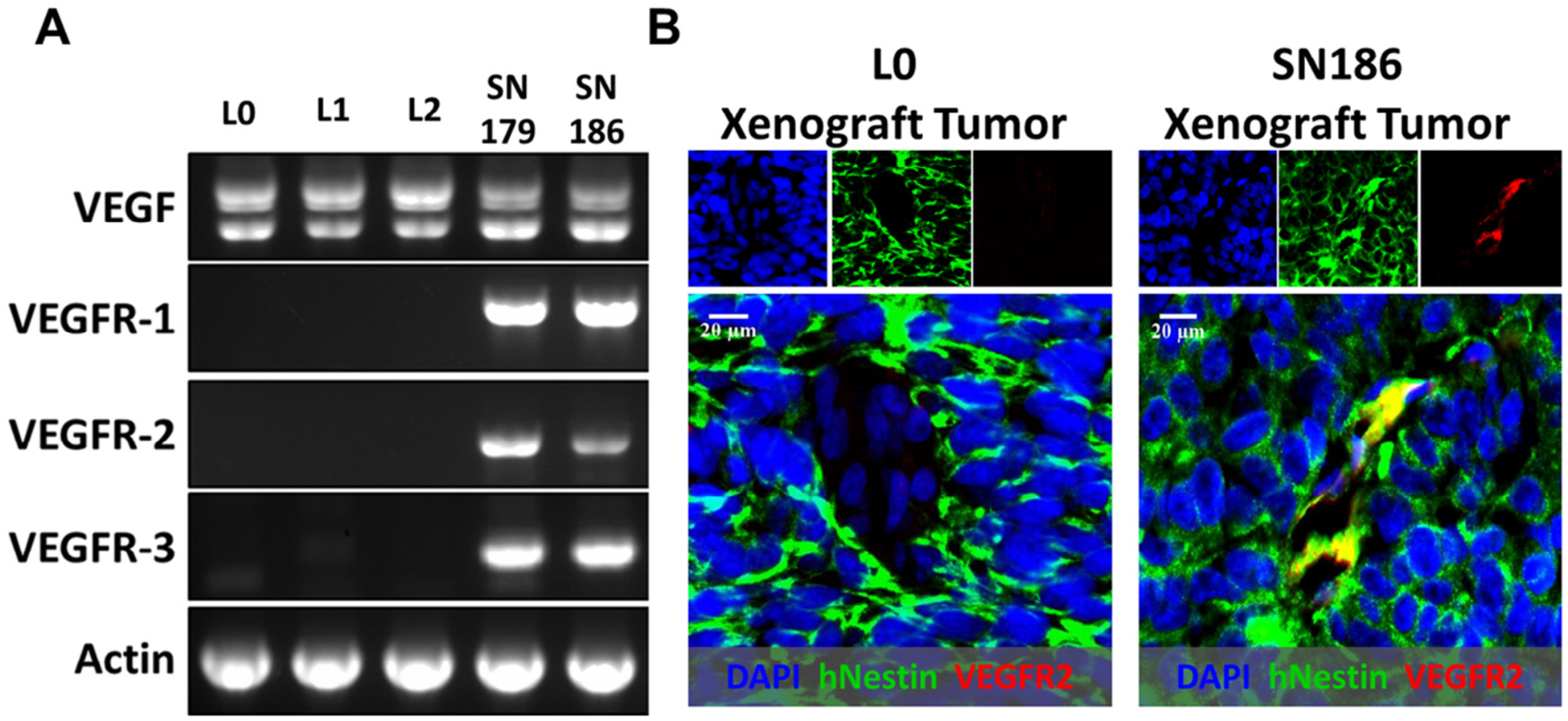

Heterogeneous expression of VEGF receptors by GBM cell lines

The mRNA expression pattern of VEGF and its three receptor isoforms, VEGFR1, VEGFR2, and VEGFR3, was evaluated in various GBM lines cultured under cancer stem cell-like conditions. While VEGF was expressed by all five GBM lines, RT-PCR analysis showed that expression of VEGFRs was varied. All three VEGFR mRNAs were found in SN179 and SN186 lines while none were detected in the L0, L1, and L2 lines (Fig. 1A). Consistent with the in vitro mRNA expression data, immunohistochemical analysis showed that VEGFR2 was detected in tumors derived from SN186 cells, but not the L0 cell line. The co-localization of VEGFR2 and human Nestin indicated that VEGFR2 was expressed by human SN186 cells (Fig. 1B). These data indicate heterogeneity in the expression of VEGFRs in different GBM cell lines and tumors.

Fig. 1.

Heterogenous expression of VEGFRs by GBM cell lines and tumors. (A) RT-PCR analysis identified VEGFR1, 2, 3 mRNAs in SN179 and SN186, but not in L0, L1, and L2 cells. VEGF mRNA was expressed by all cell lines. Actin was used as a control. (B) Immunohistochemical analysis of VEGFR2 expression (red), that co-localized with human Nestin (green), in tumors from SN186 xenograft (right), but not in tumors derived from L0 cells (left). Images were taken with a 40× objective.

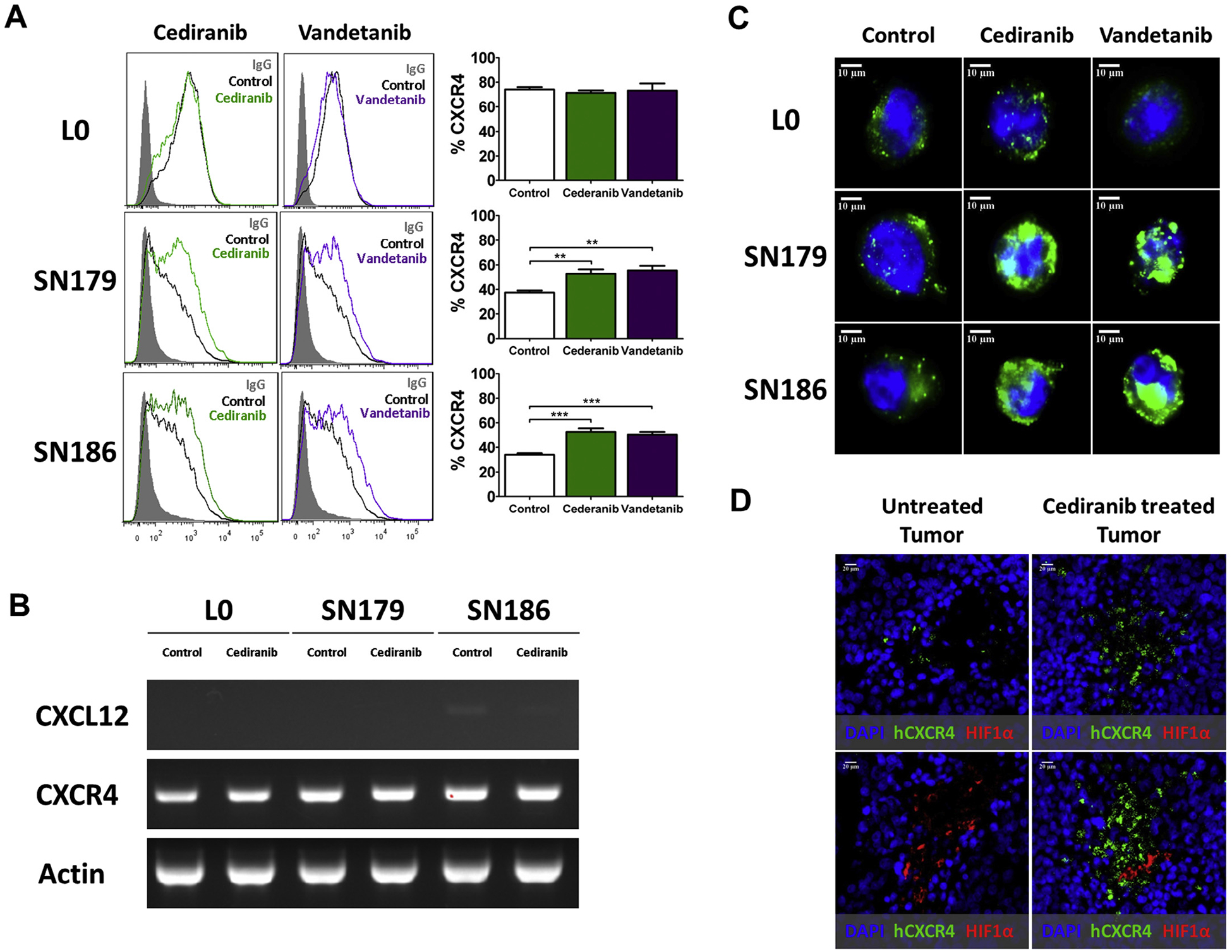

VEGFR inhibitors increased the expression of CXCR4 in GBM cell lines and xenograft tumors that are positive for VEGFRs and enhanced migration of VEGFR-expressing lines to CXCL12

The impact of VEGFR signaling inhibitors, Cediranib and Vandetanib, on the surface expression of CXCR4 in the GBM lines was examined by flow cytometry. CXCR4 expression was significantly increased in VEGFR(s)-positive SN179 and SN186 cells but not in the VEGFR(s)-negative L0 cell line, after the lines were treated with either Cediranib or Vandetanib (Fig. 2A). CXCR4 was also increased in the SN186 line with Bevacizumab treatment (data not shown). Although VEGFR inhibitors enhanced CXCR4 protein expression in SN179 and SN186, mRNA levels of CXCR4 were unaffected by the drug treatments (Fig. 2B). CXCL12 mRNA was undetected in control or Cediranib-treated cells (Fig. 2B). The increase in CXCR4 expression after treatment with these VEGFR inhibitors was further confirmed with immunocytochemistry (Fig. 2C). Consistent with the in vitro data, CXCR4 was more readily detected in VEGFR-positive SN186 derived tumors from tumor-bearing NSG mice treated with Cediranib, compared to vehicle-treated tumors. The increase in CXCR4 expression was evident in both normoxic and hypoxic zones, as determined by the relative proximity of CXCR4+ and HIF1α+ cells (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Increased CXCR4 in VEGFR-positive GBM cell lines and tumors treated with VEGFR inhibitors. (A) Flow cytometry analysis determined that CXCR4 is increased in either Cediranib or Vandetanib treated SN179 and SN186 cells, but not in L0 cells. Non-immune IgG was included as a staining control. The bar graphs represent statistical analysis of the percentage of cells expressing CXCR4 from multiple independent flow cytometry analyses. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (B) RT-PCR analysis showed no change in mRNA expression of CXCL12 and CXCR4 after Cediranib treatment in L0, SN179, SN186. Actin served as a positive control. (C) Higher expression of CXCR4 (green) was evident in SN179 and SN186 cells treated with Cediranib, compared to control-treated cells, as detected by immunofluorescent staining. (D) Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor sections from SN186 tumor bearing-NSG mice treated with Cediranib (right), or vehicle-treated tumor bearing mice (left), shows increased CXCR4 (green) in normoxic and hypoxic regions of Cediranib-treated tumors. HIF1α staining (red) was used as a marker to identify hypoxic areas of the tumor. For in vitro experiments (A–C), the cells were treated with 500 nM of Cediranib or Vandetanib for 16 hr before flow cytometry, RT-PCR, or immune-staining analyses. For the in vivo experiment (D), after 2 weeks of cell implantation, mice were treated with Cediranib daily at 6 mg/kg for 4 weeks before the tumors were isolated and subjected to immunohistochemical analysis.

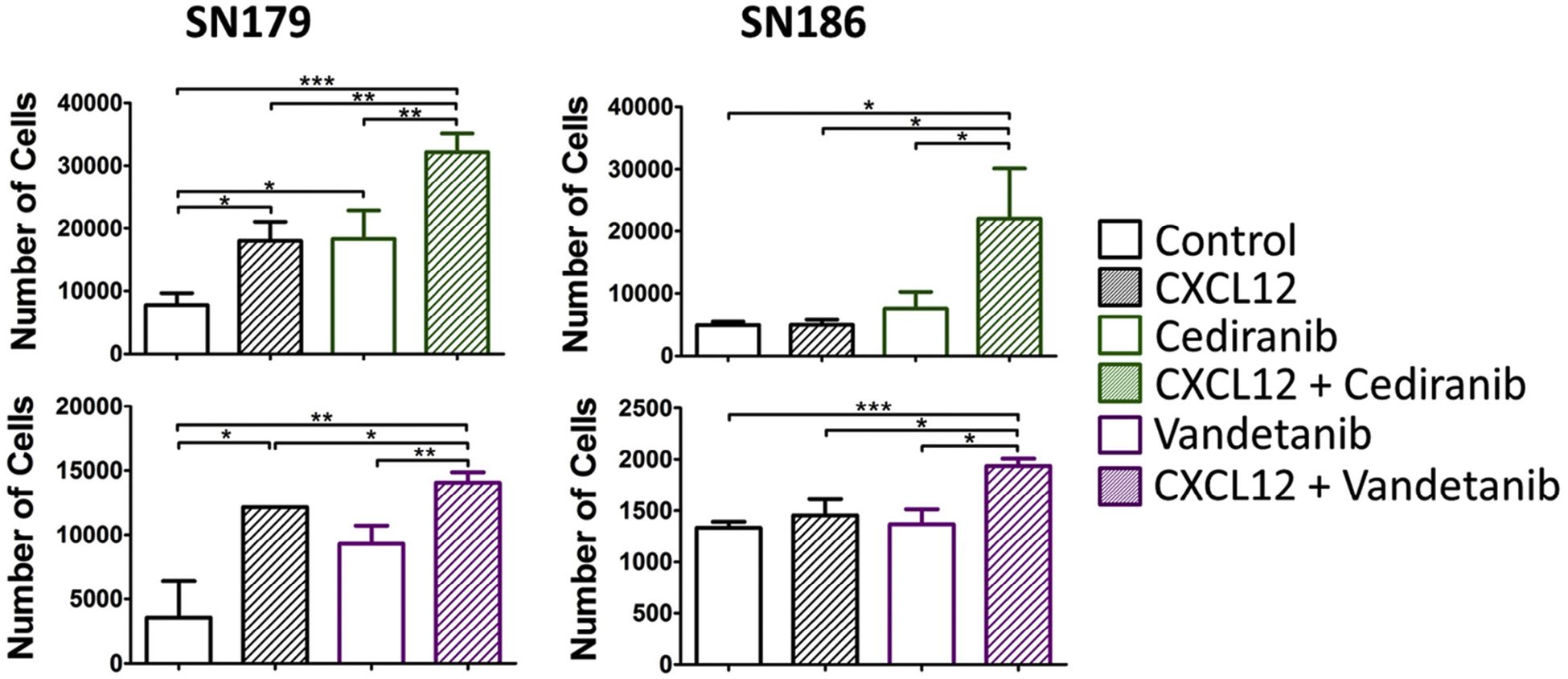

Because CXCR4 was elevated by VEGFR inhibitors, we then determined if these agents could enhance the migration of the SN179 and SN186 cells to CXCL12. Consistent with our previous results [33], in the absence of Cediranib or Vandetanib pre-treatment, CXCL12 induced the migration of SN179, but not SN186 cells. However, both Cediranib and Vandetanib pre-treatment enhanced the CXCL12 directed migration in SN179 cells; these inhibitors also increased basal migration of the SN179 cells. Both drugs induced a migratory effect of SN186 cells (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Enhanced migration of VEGFR inhibitor-treated SN179 and SN186 cells to CXCL12. Migration assays were performed with SN179 (left) and SN186 (right) cell lines in the absence or presence of CXCL12 (3 nM) in the lower chamber. Cells were treated with Cediranib or Vandetanib (500 nM) for 16 hr prior to the migration assay. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

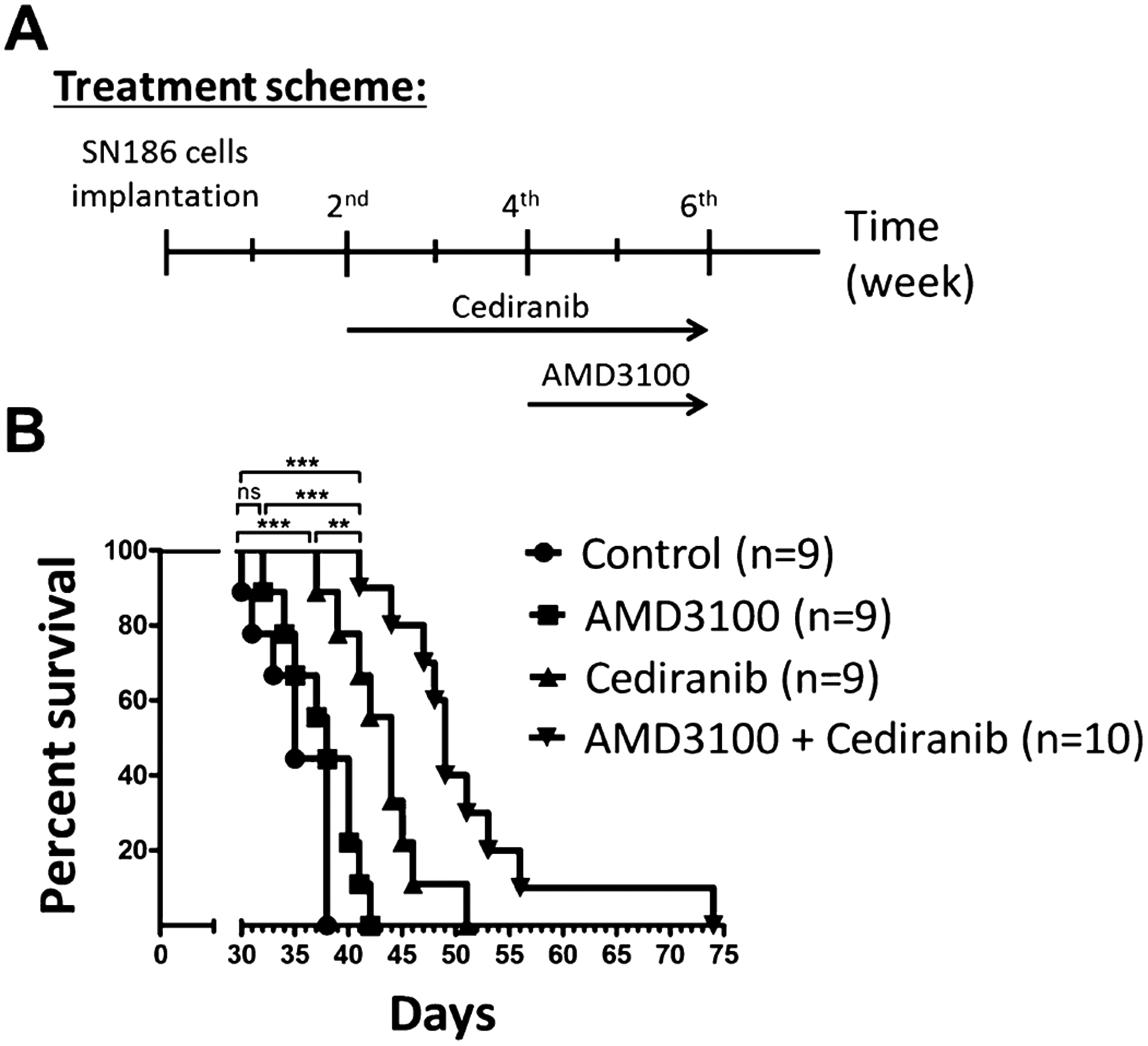

The combination of a CXCR4 antagonist and a VEGFR inhibitor increased the survival of VEGFR(s)-positive GBM bearing animals

To determine whether antagonism of CXCR4 after anti-VEGFR therapy of a VEGFR(s)-positive tumor xenograft could improve survival, SN186 cells were intracranially implanted into NSG mice and tumors were allowed to initiate for 2 weeks. Tumor-bearing animals were then treated with or without Cediranib. Following an additional two weeks, control and Cediranib-treated mice were further subdivided into vehicle and AMD3100 (CXCR4 antagonist) treatment groups (Fig. 4A). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (Fig. 4B) showed that combined treatment of Cediranib and AMD3100 provided the greatest survival advantage to tumor bearing mice, when compared to control (P < 0.0001), AMD3100 (P < 0.0001), or Cediranib (P = 0.0085) treated groups. Although single treatment of Cediranib also contributed a statistically significant benefit to animal survival (P = 0.0003), no effect of monotherapy with AMD3100 on the survival of tumor bearing mice was evident (P = 0.1027), when compared to the control-treated cohort. These results suggest that an alternative therapy scheme that targets both VEGFR and CXCR4 signaling might render an advantage over monotherapies.

Fig. 4.

Combination of Cediranib and AMD3100 prolonged survival of SN186 tumor bearing mice. (A) Treatment scheme for the survival analysis of SN186 tumor-bearing NSG mice. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that the longest survival was achieved with combined treatment (n = 10, median = 49 days), compared to vehicle-treated (n = 9, median = 35 days), single treatment with AMD3100 (n = 9, median = 38 days), or Cediranib (n = 9, median = 44 days).

VEGFR inhibitors regulated CXCR4 expression in an HGF/MET independent and TGFβ/TGFβRs dependent manner

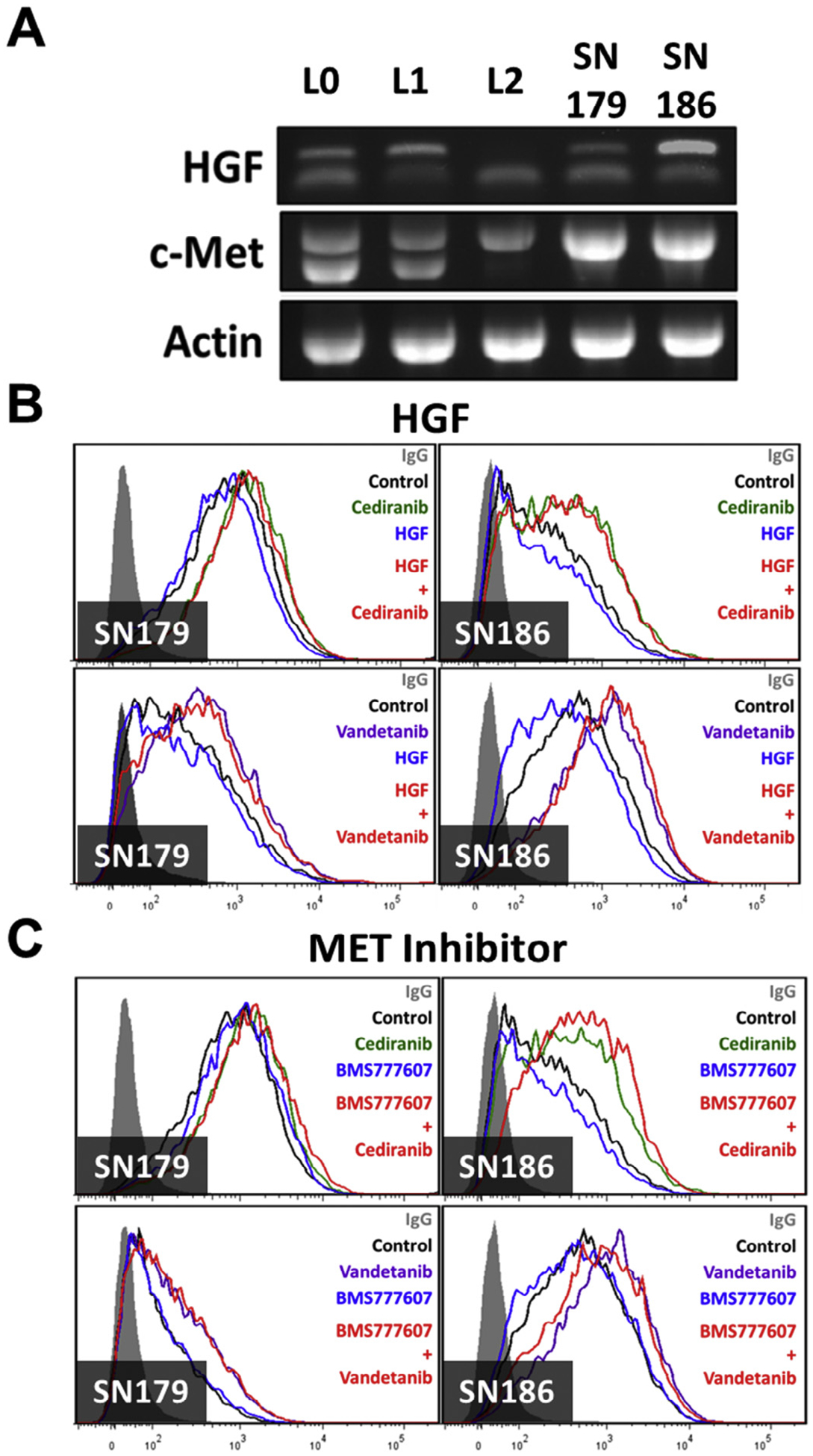

Anti-VEGF agents can regulate enhanced invasiveness in GBM by unmasking MET signaling inhibition [18]. Because MET was shown to be an upstream regulator of CXCR4 [42], the effect of HGF on CXCR4 expression was evaluated in the absence or presence of either Cediranib or Vandetanib. Flow cytometry analysis showed that exogenous HGF did not impact CXCR4 levels (Fig. 5B). The lack of an exogenous HGF effect could be due to the presence of endogenous HGF generated by these cell lines, as evidenced by RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 5A). However, a MET inhibitor, BMS777607, was unable to prevent the effects of the VEGFR inhibitors on CXCR4 expression (Fig. 5C). Taken together, the VEGFR inhibitor regulated expression of CXCR4 is independent of the HGF/MET signaling pathway.

Fig. 5.

Increased CXCR4 expression by VEGFR inhibitors is independent of HGF/MET signaling. (A) RT-PCR analysis detected HGF and MET mRNAs in all cell lines. Actin served as a control. Neither (B) recombinant HGF (100 ng/ml, top panels) nor (C) a MET signaling inhibitor BMS777607 (1 μM, bottom panels) affected the upregulation of CXCR4 by Vandetanib or Cediranib (500 nM) in SN179 (left) and SN186 (right) cell lines, as analyzed by flow cytometry.

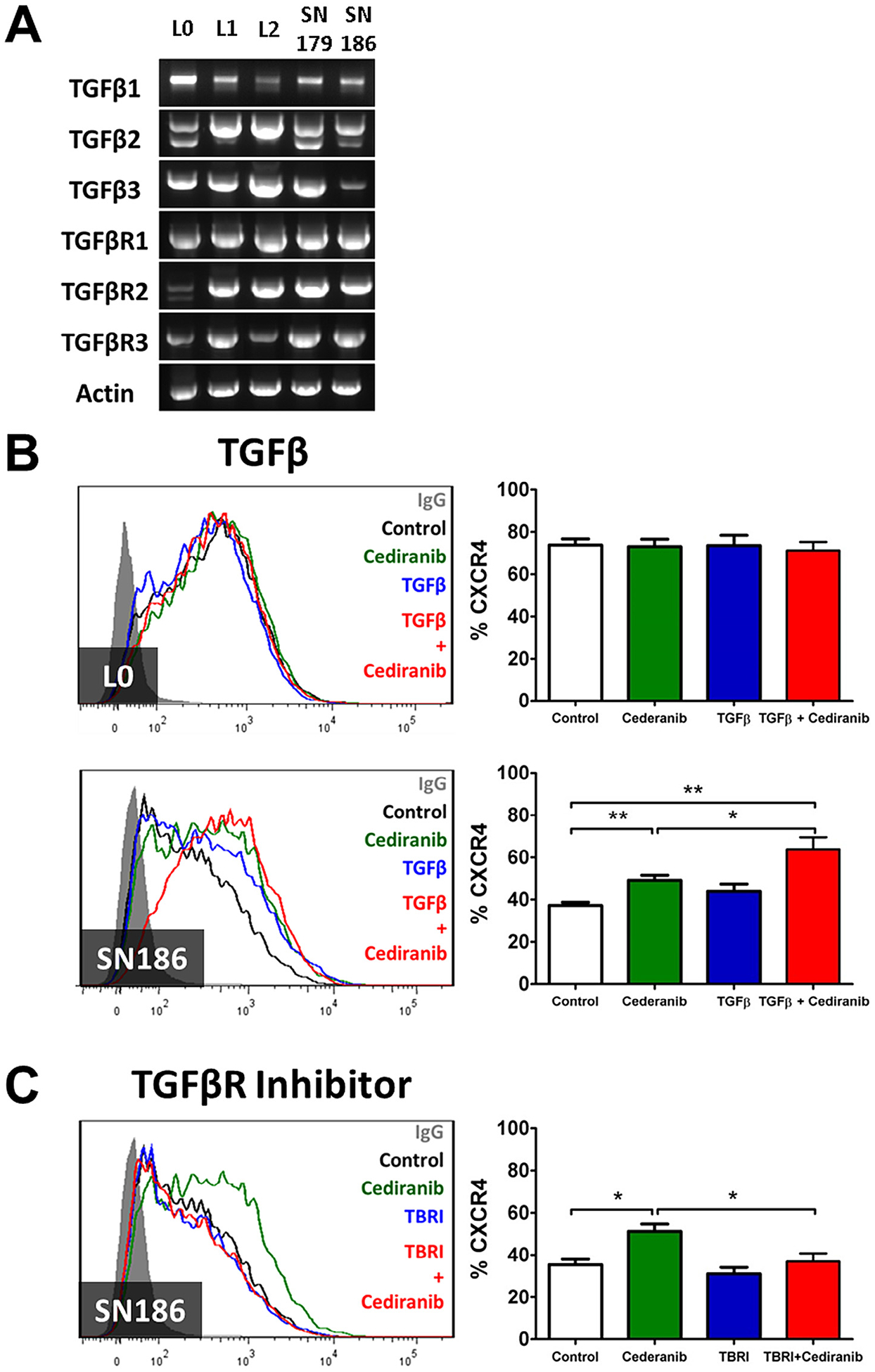

TGFβ is known for its roles in both pro- and anti-inflammatory regulation in tumor progression [43–47]. As TGFβ is highly expressed in tumors receiving anti-VEGFR treatment [48], we hypothesized that TGFβ could be a factor involved in the anti-VEGFR induced increases in CXCR4 expression. RT-PCR analysis determined that mRNA levels of all forms of TGFβ (TGFβ1, TGFβ2, TGFβ3) and all TGFβRs (TGFβR1, TGFβR2, TGFβR3) were found in all of the lines under study (Fig. 6A). Levels of TGFβ protein in L0 and SN186 cells treated with or without Cediranib were below limits of detection (data not shown). Nonetheless, TGFβ1 enhanced the Cediranib effect on CXCR4 expression in the VEGFR(s)-positive SN186, but not the VEGFR(s)-negative L0, cell line (Fig. 6B). Moreover, a TGFβR inhibitor suppressed the Cediranib stimulated expression of CXCR4 in the SN186 cells (Fig. 6C). These results support a mechanism in which the enhancement of CXCR4 expression by VEGFR inhibition is controlled by TGFβ/TGFβR signaling.

Fig. 6.

Increased CXCR4 expression by Cediranib is regulated by the TGFβ/TGFβR signaling pathway. (A) RT-PCR analysis detected TGFβ1, TGFβ2, β3, and TGFβRs in all GBM lines. (B) Recombinant TGFβ1 (5 ng/ml) enhanced the effect of Cediranib (500 nM) on CXCR4 expression in SN186, but not in L0 cells. (C) TGFβR kinase inhibitor (TBRI, 1 μM) blocked the effect of Cediranib (500 nM)-induced CXCR4 expression in SN186 cells. The bar graphs represent statistical analysis of the percentage of cells expressing CXCR4 from multiple flow cytometry analyses. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

While drugs targeting the VEGF/VEGFR pathway are now considered for GBM, aggressive tumor relapse after anti-VEGF/VEGFR treatment is a chief concern. Data from laboratory and clinical studies indicate that after initial responses to anti-VEGF/VEGFR drugs, tumors tend to grow back in a more invasive manner [9,14–16,48]. The underlying mechanisms responsible for the tumor resistance and adaptive invasive phenotype remain elusive. A previous report suggests that inhibition of VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling unmasks the activity of MET by removing protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B, thus stimulating an enhanced invasive phenotype of tumor cells through this receptor [18]. The results reported here identify a CXCR4 and TGFβR axis as an alternative mechanism by which anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapies promote progression of glioblastoma cells after anti-angiogenic therapies.

Our study identifies heterogeneity in VEGFR expression by various GBM cell lines as the mRNA levels of the three receptor isoforms were evident in some lines but not others, while VEGF was expressed by all lines under study. When comparing fold changes (≥−0.5: down-regulated, ≤0.5: up-regulated) in the expression of VEGF, VEGFR1, and VEGFR2, based on the tumor/normal tissue ratio in a screen of the TCGA database collected from patients with GBM, VEGF was identified as prominently up-regulated in 390 samples (99.2%) while only 3 samples were shown to be down-regulated (0.8%). In contrast, the change in gene expression of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 was far more heterogeneous among these samples: 197 up-regulated (77.3%) and 58 down-regulated (22.7%) with VEGFR1, 174 up-regulated (76.7%) and 53 down-regulated (23.3%) with VEGFR2 (data not shown); the gene expression of VEGFR3 was not analyzed due to the lack of data. Hence, VEGFR expression patterns in the GBM lines used in this study reflect the heterogeneity of these receptors in GBM tissues.

CXCL12 and CXCR4 are well known for their pro-migratory effects in many different types of cancer, including GBM [19,23,24,32]. Moreover, CXCL12 and CXCR4 may contribute to the insensitivity of GBM to irradiation by recruiting tumor infiltrated-CD11b+ microglia/macrophages that are responsible for the revascularization process in the tumor [30,49,50]. With regard to tumor recurrence after anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapy, this report provides the first evidence that VEGFR inhibitors (Cediranib and Vandetanib) are capable of elevating the expression of CXCR4 in GBM cell lines, as well as in Cediranib treated-xenograft tumors. While Cediranib and Vandetanib primarily affect VEGFR associated tyrosine kinases, they also impact other receptor kinases e.g. EGFR, PDGFRα/β, c-kit. The increase in CXCR4 expression by VEGFR inhibitors is likely due to VEGFR signal inhibition as this effect was only observed in VEGFR-positive, but not VEGFR-negative, GBM cell lines. Further evidence pointing to VEGF/VEGFR signaling, at least with the SN186 line, was the similar impact of Bevacizumab on the upregulation of CXCR4. The VEGFR-negative lines used here are categorized to the classical (or proliferative) subclass, based on the molecular subtype classification reported previously, as they are enriched with EGFR expression [51–53]. As such, the lack of an effect of Vandetanib in these lines suggests that EGFR is not involved in the regulation of CXCR4 by these agents.

Using pharmacological approaches, we demonstrated that the mechanism for up-regulation of CXCR4 by anti-VEGFR agents is dependent on TGFβ/TGFβRs, but not HGF/MET signaling. The presence of TGFβs and TGFβRs is well documented in GBM tumors [48,54,55]. In the U87 GBM xenograft model, expression of TGFβ was markedly increased in the tumors treated with either Bevacizumab, or Sunitinib, or the combination of Bevacizumab and Sunitinib, when compared to control treated tumors [48]. TGFβ-dependent-regulation of CXCR4 is also evident in GBM as a small-molecule inhibitor of TGFβ type 1 receptor kinase (LY364947) was shown to inhibit the increase in CXCR4 expression stimulated by radiation in murine GL261 neurospheres [49]. Coupling these observations, our data support an interaction among three signaling pathways that include VEGF/VEGFRs, TGFβ/TGFβRs, and CXCL12/CXCR4. Inhibition of VEGF/VEGFR signaling induces TGFβ/TGFβR signaling activity, and subsequent stimulation of the CXCL12/CXCR4 pathway which could further promote tumor progression. Regulation of CXCR4 by TGFβ was not observed in all lines, e.g. L0. CXCR4 expression in this line may be at a maximal level and thus unregulatable by exogenous TGFβ. Alternatively, CXCR4- and TGFβR-expressing subpopulations of cells may be distinct.

The combination of Bevacizumab and chemotherapy exhibits, at best, a trend in clinical effectiveness with selective cytotoxic agents, compared to monotherapies [17,56–58]. As such, the combination of anti-angiogenic therapies with molecularly targeted agents needs to be considered. Our study provides evidence for an enhanced survival effect on AMD3100 and Cediranib treated GBM-bearing mice and represents a significant scientific rationale for clinical evaluation of combined therapy that targets both VEGF/VEGFRs and CXCL12/CXCR4. Published studies showed that AMD3100 treatment significantly impaired intracranial growth of U87 GBM xenografts [21] as well as the migration of U87 and LN308 cell lines under hypoxic conditions [24]. Using the U87 xenograft model, Barone et al. reported enhanced survival combining anti-VEGF antibody and CXCR4 antagonist [59]. Our study is distinguished from this latter one by the use of GBM lines cultured under stem cell-like conditions and evidence supporting a mechanism for increased CXCR4 expression and function in GBM cells that is dependent on TGFβR signaling.

In conclusion, our results provide evidence for the involvement of CXCR4 in the progression of GBM with anti-angiogenic therapies that involves mutual interaction among three independent signaling pathways CXCL12/CXCR4, TGFβ/TGFβR, and VEGF/VEGFR. These observations not only contribute to a better understanding of the molecular complexity of mechanisms that drive tumor malignancy and resistance to current therapies in GBM patients, but also suggest a strategy of targeting all of these pathways simultaneously, to enhance the effectiveness of GBM treatment.

Acknowledgement

The research reported in this study was partially funded by the Florida Center for Brain Tumor Research (to J.K.H.).

Abbreviations:

- GBM

glioblastoma

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor beta

- TGFβR

transforming growth factor beta receptor

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- MET

mesenchymal epithelial transition factor

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any conflict of interests to report related to this manuscript.

References

- [1].Schneider T, et al. , Gliomas in adults, Dtsch. Arztebl. Int 107 (2010) 799–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].McComb RD, et al. , The biology of malignant gliomas – a comprehensive survey, Clin. Neuropathol 3 (1984) 93–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Clarke J, et al. , Recent advances in therapy for glioblastoma, Arch. Neurol 67 (2010) 279–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Plate KH, et al. , Up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor and its cognate receptors in a rat glioma model of tumor angiogenesis, Cancer Res. 53 (1993) 5822–5827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Plate KH, et al. , Vascular endothelial growth factor and glioma angiogenesis: coordinate induction of VEGF receptors, distribution of VEGF protein and possible in vivo regulatory mechanisms, Int. J. Cancer 59 (1994) 520–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Samoto K, et al. , Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its possible relation with neovascularization in human brain tumors, Cancer Res. 55 (1995) 1189–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hofer S, et al. , Clinical outcome with bevacizumab in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma treated outside clinical trials, Acta Oncol. 50 (2011) 630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Reardon DA, et al. , Glioblastoma multiforme: an emerging paradigm of anti-VEGF therapy, Expert Opin. Biol. Ther 8 (2008) 541–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Iwamoto FM, et al. , Bevacizumab for malignant gliomas, Arch. Neurol 67 (2010) 285–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Batchelor TT, et al. , AZD2171, a pan-VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, normalizes tumor vasculature and alleviates edema in glioblastoma patients, Cancer Cell 11 (2007) 83–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Drappatz J, et al. , Phase I study of vandetanib with radiotherapy and temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma, Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys 78 (2010) 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gilbert MR, et al. , A randomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma, N. Engl. J. Med 370 (2014) 699–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chinot OL, et al. , Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy-temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma, N. Engl. J. Med 370 (2014) 709–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bergers G, et al. , Modes of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy, Nat. Rev. Cancer 8 (2008) 592–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Iwamoto FM, et al. , Patterns of relapse and prognosis after bevacizumab failure in recurrent glioblastoma, Neurology 73 (2009) 1200–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].de Groot JF, et al. , Tumor invasion after treatment of glioblastoma with bevacizumab: radiographic and pathologic correlation in humans and mice, Neuro-Oncol. 12 (2010) 233–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Narayana A, et al. , A clinical trial of bevacizumab, temozolomide, and radiation for newly diagnosed glioblastoma, J. Neurosurg 116 (2012) 341–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lu KV, et al. , VEGF inhibits tumor cell invasion and mesenchymal transition through a MET/VEGFR2 complex, Cancer Cell 22 (2012) 21–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Koshiba T, et al. , Expression of stromal cell-derived factor 1 and CXCR4 ligand receptor system in pancreatic cancer: a possible role for tumor progression, Clin. Cancer Res 6 (2000) 3530–3535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hall JM, et al. , Stromal cell-derived factor 1, a novel target of estrogen receptor action, mediates the mitogenic effects of estradiol in ovarian and breast cancer cells, Mol. Endocrinol 17 (2003) 792–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rubin JB, et al. , A small-molecule antagonist of CXCR4 inhibits intracranial growth of primary brain tumors, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 100 (2003) 13513–13518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Burns JM, et al. , A novel chemokine receptor for SDF-1 and I-TAC involved in cell survival, cell adhesion, and tumor development, J. Exp. Med 203 (2006) 2201–2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ehtesham M, et al. , CXCR4 expression mediates glioma cell invasiveness, Oncogene 25 (2006) 2801–2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zagzag D, et al. , Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and VEGF upregulate CXCR4 in glioblastoma: implications for angiogenesis and glioma cell invasion, Lab. Invest 86 (2006) 1221–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zagzag D, et al. , Hypoxia- and vascular endothelial growth factor-induced stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha/CXCR4 expression in glioblastomas: one plausible explanation of Scherer’s structures, Am. J. Pathol 173 (2008) 545–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mantovani A, et al. , The chemokine system in cancer biology and therapy, Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 21 (2010) 27–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sun X, et al. , CXCL12/CXCR4/CXCR7 chemokine axis and cancer progression, Cancer Metastasis Rev. 29 (2010) 709–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Duda DG, et al. , CXCL12 (SDF1alpha)-CXCR4/CXCR7 pathway inhibition: an emerging sensitizer for anticancer therapies, Clin. Cancer Res 17 (2011) 2074–2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ping YF, et al. , The chemokine CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4 promote glioma stem cell-mediated VEGF production and tumour angiogenesis via PI3K/AKT signalling, J. Pathol 224 (2011) 344–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tseng D, et al. , Targeting SDF-1/CXCR4 to inhibit tumour vasculature for treatment of glioblastomas, Br. J. Cancer 104 (2011) 1805–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hattermann K, et al. , The chemokine receptor CXCR7 is highly expressed in human glioma cells and mediates antiapoptotic effects, Cancer Res. 70 (2010) 3299–3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Komatani H, et al. , Expression of CXCL12 on pseudopalisading cells and proliferating microvessels in glioblastomas: an accelerated growth factor in glioblastomas, Int. J. Oncol 34 (2009) 665–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Liu C, et al. , Expression and functional heterogeneity of chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CXCR7 in primary patient-derived glioblastoma cells, PLoS ONE 8 (2013) e59750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Galli R, et al. , Isolation and characterization of tumorigenic, stem-like neural precursors from human glioblastoma, Cancer Res. 64 (2004) 7011–7021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sarkisian MR, et al. , Detection of primary cilia in human glioblastoma, J. Neurooncol 117 (2014) 15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Silver DJ, et al. , Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans potently inhibit invasion and serve as a central organizer of the brain tumor microenvironment, J. Neurosci 33 (2013) 15603–15617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Siebzehnrubl FA, et al. , The ZEB1 pathway links glioblastoma initiation, invasion and chemoresistance, EMBO Mol. Med 5 (2013) 1196–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Deleyrolle LP, et al. , Evidence for label-retaining tumour-initiating cells in human glioblastoma, Brain 134 (2011) 1331–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Deleyrolle LP, et al. , Determination of somatic and cancer stem cell self-renewing symmetric division rate using sphere assays, PLoS ONE 6 (2011) e15844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Liu C, et al. , Chemokine receptor CXCR3 promotes growth of glioma, Carcinogenesis 32 (2011) 129–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hothi P, et al. , High-throughput chemical screens identify disulfiram as an inhibitor of human glioblastoma stem cells, Oncotarget 3 (2012) 1124–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Esencay M, et al. , HGF upregulates CXCR4 expression in gliomas via NF-kappaB: implications for glioma cell migration, J. Neurooncol 99 (2010) 33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Roth P, et al. , Integrin control of the transforming growth factor-β pathway in glioblastoma, Brain 136 (2013) 564–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Gold LI, The role for transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) in human cancer, Crit. Rev. Oncog 10 (1999) 303–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fontana A, et al. , Expression of TGF-beta 2 in human glioblastoma: a role in resistance to immune rejection, Ciba Found. Symp 157 (1991) 232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kuczynski EA, et al. , VEGFR2 expression and TGF-β signaling in initial and recurrent high-grade human glioma, Oncology 81 (2011) 126–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Zhang M, et al. , Blockade of TGF-β signaling by the TGFβR-I kinase inhibitor LY2109761 enhances radiation response and prolongs survival in glioblastoma, Cancer Res. 71 (2011) 7155–7167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Piao Y, et al. , Glioblastoma resistance to anti-VEGF therapy is associated with myeloid cell infiltration, stem cell accumulation, and a mesenchymal phenotype, Neuro-Oncol. 14 (2012) 1379–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hardee ME, et al. , Resistance of glioblastoma-initiating cells to radiation mediated by the tumor microenvironment can be abolished by inhibiting transforming growth factor-β, Cancer Res. 72 (2012) 4119–4129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Maddirela DR, et al. , MMP-2 suppression abrogates irradiation-induced microtubule formation in endothelial cells by inhibiting αvβ3-mediated SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling, Int. J. Oncol 42 (2013) 1279–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mischel PS, et al. , Identification of molecular subtypes of glioblastoma by gene expression profiling, Oncogene 22 (2003) 2361–2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Brennan C, et al. , Glioblastoma subclasses can be defined by activity among signal transduction pathways and associated genomic alterations, PLoS ONE 4 (2009) e7752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Verhaak RG, et al. , Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1, Cancer Cell 17 (2010) 98–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Eichhorn PJ, et al. , USP15 stabilizes TGF-β receptor I and promotes oncogenesis through the activation of TGF-β signaling in glioblastoma, Nat. Med 18 (2012) 429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Beier CP, et al. , The cancer stem cell subtype determines immune infiltration of glioblastoma, Stem Cells Dev. 21 (2012) 2753–2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kreisl TN, et al. , Phase II trial of single-agent bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab plus irinotecan at tumor progression in recurrent glioblastoma, J. Clin. Oncol 27 (2009) 740–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Møller S, et al. , A phase II trial with bevacizumab and irinotecan for patients with primary brain tumors and progression after standard therapy, Acta Oncol. 51 (2012) 797–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Reardon DA, et al. , Phase II study of carboplatin, irinotecan, and bevacizumab for bevacizumab naïve, recurrent glioblastoma, J. Neurooncol 107 (2012) 155–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Barone A, et al. , Combined VEGF and CXCR4 antagonism targets the GBM stem cell population and synergistically improves survival in an intracranial mouse model of glioblastoma, Oncotarget 5 (2014) 9811–9822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]