Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Pancreatic cystic lesions (PCLs) may be precancerous. Those likely to harbor high-grade dysplasia (HGD) or pancreatic cancer (PC) are targets for surgical resection. Current algorithms to predict advanced neoplasia (HGD/PC) in PCLs lack diagnostic accuracy. In pancreatic tissue and cystfluid (CF) from PCLs, we sought to identify and validate novel methylated DNA markers (MDMs) that discriminate HGD/PC from low-grade dysplasia (LGD) or no dysplasia (ND).

METHODS

From an unbiased whole-methylome discovery approach using predefined selection criteria followed by multistep validation on case (HGD or PC) and control (ND or LGD) tissues, we identified discriminant MDMs. Top candidate MDMs were then assayed by quantitative methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction on archival CF from surgically resected PCLs.

RESULTS

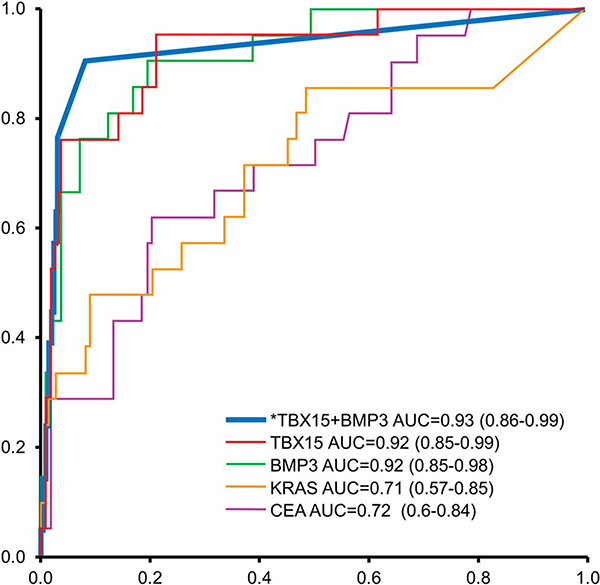

Of 25 discriminant MDMs identified in tissue, 13 were selected for validation in 134 CF samples (21 cases [8 HGD, 13 PC], 113 controls [45 ND, 68 LGD]). A tree-based algorithm using 2 CF-MDMs (TBX15, BMP3) achieved sensitivity and specificity above 90%. Discrimination was significantly better by this CF-MDM panel than by mutant KRAS or carcinoembryonic antigen, with areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.93 (95% confidence interval: 0.86–0.99), 0.71 (0.57–0.85), and 0.72(0.60–0.84), respectively. Cutoffs for the MDM panel applied to an independent CF validation set (31 cases, 56 controls) yielded similarly high discrimination, areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve 5 0.86 (95% confidence interval: 0.77–0.94, P = 0.2).

DISCUSSION

Novel MDMs discovered and validated in tissue accurately identify PCLs harboring HGD/PC. A panel of 2 MDMs assayed in CF yielded results with potential to enhance current risk prediction algorithms. Prospective studies are indicated to optimize and further evaluate CF-MDMs for clinical use.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cystic lesions (PCLs) are common, and widespread use of abdominal cross-sectional imaging has increased their detection. Prevalence estimates of PCLs range widely from 2.4% to 41.3% based on incidental findings from routine abdominal imaging, with highest estimates coming from more recent studies using high-resolution MRI (1–3). The vast majority of PCLs harbor either no dysplasia (ND) or low-grade dysplasia (LGD) only, findings that do not justify the morbidity and mortality risks associated with pancreatic resection. Although there is expert consensus that PCLs harboring high-grade dysplasia (HGD) or early invasive cancer should be selected for surgical resection, current algorithms for detection of such advanced neoplasia are imperfect.

Although the relative risk of pancreatic cancer (PC) is higher in patients with PCLs compared with the general population, the annual incidence of PC in PCLs is very low (<1%), posing unique surveillance and management challenges (4,5). Among the different subsets of precancerous PCLs, the risk of malignant degeneration over time is highest in intraductal papillary muconous neoplasms (IPMNs). A recent metanalysis estimated the cumulative incidence of PC in unresected IPMNs at 10 years to be 8%–25% (6). This risk of malignant degeneration appears to be much lower in isolated branch-duct disease (7). Current guidelines that are used to inform management of PCLs include the Fukuoka guidelines, which classify cysts as having “worrisome” or “high-risk” features based on clinical, laboratory, and morphologic criteria (8,9), the American Gastroenterology Association guidelines (10), and the recently published European guidelines (11). The Fukuoka criteria for “high-risk” PCLs have been shown to have a sensitivity of 56%–81% and a specificity of 69%–73% (12,13) for detecting cancer in PCLs. In the finding of cancer/HGD in surgically resected PCLs, the American Gastroenterology Association guidelines have been reported to have 75%–83% sensitivity at 69%–74% specificity (14). The Fukuoka guidelines and the Sendai guidelines that preceded it greatly reduced the need for pancreatic resections by risk-stratifying PCLs. However, the suboptimal specificity of existing guidelines coupled with the low prevalence of advanced neoplasia in these PCLs results in a significant number of unnecessary pancreatic resections. In addition, the risk of a missed cancer in PCLs is not insignificant (12,13).

A cyst fluid (CF) test that accurately detects advanced neoplasia in patients with “worrisome” and “high-risk” PCLs would be a valuable addition to current risk prediction guidelines. CF cytology has poor overall sensitivity for detection of HGD or PC (15). Previous studies using CF carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and more recently GNAS and KRAS mutations, alone or in combination with clinical features, do not reliably identify advanced neoplasia (16–18). Aberrant DNA methylation events occur at progressive stages through the oncogenic cascade, some present in dysplasia but not metaplasia and others emerge primarily at the invasive cancer stage—a feature that can be exploited for specific clinical applications. This epigenetic phenomenon is likely to be an important driver in the neoplastic progression of PCLs (19), and specific loci of such aberrant methylation offer potentially valuable diagnostic markers. In earlier studies, we have demonstrated strong association of novel methylated DNA markers (MDMs) with PC and discrimination of cancer from benign controls (20). Other investigators have recently reported a study of MDMs in pancreatic CF conducted in parallel to our own work (21). In the present study, we aimed to discover and validate MDMs that discriminate PCLs harboring HGD or PC from those with LGD or ND, initially in pancreatic tissue and subsequently in CF.

METHODS

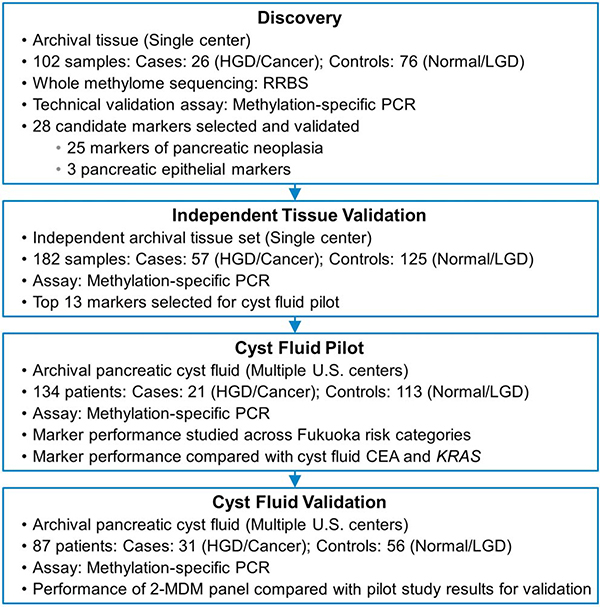

Study overview

Four sequential studies were performed (Figure 1). In the first, we aimed to discover and perform technical validation for pancreatic tissue MDM candidates that discriminate a case group with high-grade precursors (IPMN-HGD, PanIN-3) or invasive PC from a control group with either normal pancreas or low-grade precursor lesions (IPMN-low grade dysplasia [IPMN-LGD], PanIN-1, and PanIN-2). In the second study, we aimed to biologically validate these findings in an independent set of tissue samples. In a subsequent multicenter case-control study, we explored the detection accuracy of selected MDM candidates for advanced neoplasia in PCLs by their blinded assay in CF and compared MDM distributions in CF with those of CEA and mutant KRAS. Finally, in an independent multicenter effort, we validated the performance of the CF MDM panel identified in the pilot phase. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at all participating centers.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. HGD, harbor high-grade dysplasia; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; MDM, methylated DNA marker; RRBS, reduced representation bisulfite sequencing.

Biospecimen sources and assay techniques

Tissue samples for discovery (fresh frozen and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded [FFPE]) and biological validation (independent set of FFPE samples) were selected from existing institutional cancer registries at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, and were reviewed by an expert pathologist (T.C.S.) to confirm correct classification and to guide macrodissection. All pancreatic tissues were collected by the Mayo Clinic SPORE in Pancreatic Cancer Patient Registry and Tissue Core. From a multicenter collaborative effort, archival CF previously obtained by cyst puncture during endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) or surgery was used for the CF pilot and validation phases. Clinical and demographic data, preoperative imaging, and surgical pathology for study subjects were reviewed at each center by site-specific principal investigators and the information was shared using predesigned study forms. Based on the single-observer review (S.M.) of study forms and blinded histological diagnosis and CF results, subjects were classified as Fukuoka worrisome (F-WR) or high risk (F-HR). PCLs that did not satisfy worrisome or high-risk criteria were designated as low risk (F-LR).

Assay techniques

Tissue discovery

An unbiased whole-methylome discovery approach, referred to as reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS), was used to identify discriminant candidate MDMs. DNA was extracted and purified from fresh-frozen tissues (PC, NP) and buffy coat samples using the QIAamp Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). DNA from FFPE samples (HGD, LGD) were prepared using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen). The FFPE DNA was further purified using AMPure XP SPRI beads to select for fragments > 500 bp (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Sequencing library preparation followed the Meissner procedure with modifications where necessary (22). Briefly, DNA samples (300 ng) were fragmented by digestion with MspI, end-repaired and A-tailed with Klenow fragment (3’−5’ exo-), and ligated overnight to methylated TruSeq adapters (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Samples then underwent bisulfite conversion (twice) using a modified EpiTect protocol (Qiagen). qPCR was used to determine the optimal enrichment Ct (LightCycler 480—Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and samples were subsequently amplified with PfuTurbo Cx hotstart for 12–16 cycles dependent on the qPCR amplification profile (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). Samples were AMPure bead purified and then tested on the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent) to assess the DNA size distribution of the enrichment. Size selection of 40–280 bp inserts was performed using AMPure beads with buffer cutoffs of 0.7X—1.1X sample volume. Samples were combined (equimolar) into 4-plex libraries based on a randomization scheme and tested with the bioanalyzer for final size verification.

Sequencing was performed by the Next Generation Sequencing Core at the Mayo Clinic Medical Genome Facility on the Illumina HiSeq 2000. Reads were unidirectional for 101 cycles. The standard Illumina pipeline was run for the primary analysis. Streamlined analysis and annotation pipeline-RRBS was used for quality scoring, sequence alignment, annotation, and methylation extraction (23).

Tissue validation

Genomic DNA was prepared using QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kits (Qiagen) and bisulfite converted using the EZ-96 DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). Amplification primers were designed from marker sequences using either Methprimer software (University of California, San Francisco, CA) or MSPPrimer (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) and synthesized commercially (IDT, Coralville, IA). Assays were rigorously tested and optimized by SYBR Green qPCR (Roche) on bisulfite converted (methylated and unmethylated genomic DNA) and unconverted controls. Assays which cross-reacted with negative controls were either redesigned or discarded. Melt curve analysis was followed to ensure specific amplification was occurring.

Quantitative methylation specific PCR was performed using the LightCycler 480 instrument on 2 μL of converted DNA in a total reaction volume of 25 μL. Standards were derived from serially diluted universal methylated DNA (Zymo Research). Testing was performed first on the discovery samples to verify RRBS results (technical validation). Subsequent blinded testing on DNA from an independent set of macrodissected tissues targeted selected MDM candidates using methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (biological validation). Raw marker levels in both validation sets were standardized to LRRC4, identified in this study as a marker for pancreatic epithelia-derived genomic DNA.

Pilot testing and validation in CF

DNA was extracted from 0.2 mL CF using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) and bisulfite treated by the EZ-96 DNA Methylation kit (Zymo Research). Selected MDMs were then assayed by methylation-specific PCR, as above. β-actin was used to assess total genomic copies. Mutant KRAS (7 mutations) was assayed by Quantitative Allele-specific Real-time Target and Signal Amplification technology and CEA, by a commercial method (MILLIPLEX MAP Kit).

Statistical analyses

Tissue discovery

The primary comparison of interest was the methylation difference between pancreatic neoplasia cases, pancreas controls, and buffy coat controls at each mapped CpG. CpG islands are biochemically defined by an observed to expected CpG ratio >0.6. However, for this model, tiled units of “differentially methylated regions (DMRs)” were created based on distance between CpG site locations for each chromosome. Islands with <5 CpGs were excluded. Individual CpG sites were considered for differential analysis only if the total depth of coverage per disease group was ≥200 reads (an average of 10 reads/subject) and the variance of %-methylation was >0 (noninformative CpGs were excluded). Read-depth criteria were based on the desired statistical power of 80% (2-sided significance level of 5%) to detect a 10% difference in the %-methylation between any 2 groups; this required a minimum sample size of 18 for each group. Statistical significance was determined by logistic regression of the methylation percentage per DMR, based on read counts. To account for varying read depths across individual subjects, an overdispersed logistic regression model was used, where dispersion parameter was estimated using the Pearson χ2 statistic of the residuals from fitted model. DMRs, ranked according to their significance level, were further considered if %-methylation in tissue and buffy coat controls, combined, was ≤1% but ≥10% in cases.

The criteria we used to identify and rank marker regions were tailored toward the goal of being able to design methylation-specific amplification assays. The 4 principal filters were (i) DMR identification using defined CpG density criteria (5–20 CpGs/100 bp) and beta regression modeling, (ii) receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, (iii) case-group methylation differentials and fold-change ratios (with respect to either normal tissue or normal leukocytes), and iv) CpG comethylation over the region (in cases) and lack of comethylation (in controls). Two comparisons were performed with separate cohorts: PC vs “normal” pancreas samples—normal meaning resected, histologically verified, normal pancreas margins in patients who underwent resection of islet cell cancers or serous cystadenomas; and PanIN-3 vs combined PanIN-2, PanIN-1, and IPMN-LGD samples. This was necessitated by the nature of the samples; the cancers and resected normal margins were frozen tissues and the dysplastic samples were FFPE tissues. The compromised DNA representation in the latter, because of the harshness of the fixation process, results in reduced sequencing coverage and an altered footprint. To avoid technique-related artifacts, the DMR calling pipeline and statistical comparisons were made between groups with similar DNA integrity characteristics.

Tissue validation/pilot testing in CF

Distribution of marker values in independent tissues and CF within each lesion category was summarized using box plots, and the association of these markers with the dysplasia grade estimated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The sensitivity of each marker along with 95% 2-sided confidence intervals (CIs) was estimated at the 90th, 95th, and 100th percentile values of the nondsyplastic/LGD patients. Marker accuracy for discrimination of cases (HGD/PC) vs controls (Nondysplastic/LGD) was further assessed using ROCs. A combination of markers was assessed with regression partition trees (rPart). The total number of MDMs selected to be in the tree was determined through cross-validation. Bootstrap cross-validation for the entire panel of MDMs and the relative importance of individual MDMs was assessed using random forest regression (rForest; the sample size for the tissue validation provided greater than 95% power to detect an area under the ROC curve [AUC] value of 0.85 or greater compared to the null value of 0.7 [1-sided significance level of 5%]) for any single marker. For the CF cohort, this similar comparison achieved 76% power. No adjustments for multiple testing were performed.

Validation in CF

The trained rPart and rForest trees from the Pilot phase where frozen at there estimated values and applied directly to the MDM results obtained from an independent set of CF samples. Clinical details of the independent set of CF samples were released to the analysis team (independent of manuscript, statistician D.W.M) only after the MDM results were generated. The actual performance of the trained models was summarized as sensitivity, specificity, and AUC with corresponding 95% CIs.

RESULTS

Tissue discovery

Cases comprised 18 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and 8 HGD (PanIN-3), and controls included 18 normal pancreas; 47 LGD (29 IPMN-LGD, 18 PanIN-1 or 2) (Figure 1). We also studied 11 normal white blood cell (buffy coat) controls provided by Mayo Clinic Biospecimens Archive Linking Investigators and Clinicians to GIH Cell Signalling Research Clinical Core. Buffy coat was also evaluated as a control to exclude MDMs present in inflammatory cells and in normal circulation.

Nineteen DMRs were identified from the PC vs normal tissue analysis using the 4 criteria outlined above in statistical methods (see Table 1, Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/A190). Individual areas under the ROC curve ranged from 0.66 to 0.96 (P-value < 0.001—0.08). These DMRs exhibited strong contiguous CpG methylation (>10%) and methylation fold change ratios >20. Several DMRs with lower individual AUCs (<0.80) were included in the selection for their ability to potentially complement clinical sensitivity in a multimarker panel. In addition, 3 epithelial-specific regions were chosen. These DMRs exhibit robust methylated signals in both pancreatic cases and controls (>20%), but very little (<1%) in white blood cells and other hematopoietic cell types, and represent candidate normalizing MDMs. The HGD vs LGD comparison yielded 6 additional DMRs with AUCs of 0.70–0.87 (P-value < 0.001) (see Table 1, Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/A190). Performance characteristics of all candidate MDMs were confirmed by quantitative methylation specific PCR assay on the discovery samples (technical validation).

Tissue validation

For the biological independent tissue validation, cases included 30 PDAC and 27 HGD lesions (4 PanIN-3, 22 IPMN-HGD, 1 Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm [MCN]-HGD); controls included 31 normal pancreas, 88 LGD lesions (36 IPMN-LGD, 44 PanIN-1/2, 8 MCN-LGD), and 6 serous-cystic neoplasms (Figure 1). DMRs selected as candidate MDMs along with their respective AUCs are delineated (see Table 2, Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/A190). Average case/control methylation ratios were in the 2.5–9 fold range. Our selection criteria were as follows: AUC ≥ 0.75, white blood cells methylation less than 2%, and strong methylation positivity (15% or greater) in cases. The analytical performance of the qPCR assays also influenced selection (e.g., specificity of amplification, dilution linearity, CVs of standard and controls, etc.). Based on their performance characteristics, 13 MDMs were chosen to take forward into the CF pilot (see Table 3, Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/A190). Distribution plots of these MDMs across individual tissue categories illustrate clearly the much higher methylation levels in cases (IPMN-HGD, PanIN-3, and PDAC) than controls (see Figure 1, Supplementary Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/AJG/A191).

Pilot testing in CF

Overall performance

Of 134 pancreatic cysts (41 intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN), 35 MCN, 23 serous cystadenoma, 13 cystic adenocarcinoma (3 IPMN, 1 MCN, 9 indeterminate precursor), and 22 inflammatory or other nondysplastic cysts), we categorized 21 as cases (8 HGD, 13 adenocarcinoma) and 113 as controls (45 ND, 68 LGD) (Figure 1). Median age (IQR) was 71 years (56–77) for cases and 61 years (46–69) for controls (P < 0.01); 61% of cases and 31% of controls were men (P = 0.034) (Table 1). The groups were comparable with regard to smoking, personal history of non-PC, and family history of PC. CF was collected at the time of surgery in most study subjects with the remaining collected at preoperative EUS (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical features in cases and controls from cyst fluid pilot and validation sets

| Pilot |

Validation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, N = 21 | Controls, N = 113 | Cases, N = 31 | Controls, N = 56 | |

| Ageb,c | 71 (56,77) | 61 (46,69) | 72 (66,79) | 63 (50, 70) |

| Male sexa | 11 (61%) | 31 (32%) | 13 (42%) | 36 (64%) |

| Smoking | 10 (48%) | 43 (38%) | 19 (61%) | 27 (48%) |

| Personal history of nonpancreatic cancer | 5 (28%) | 14 (15%) | 9 (29%) | 8 (14%) |

| Family history of pancreatic cancer | 1 (6%) | 7 (7%) | 3 (10%) | 4 (7%) |

| Collection method (surgery)c | 18 (86%) | 78 (69%) | 29 (94%) | 52 (93%) |

P < 0.05 in Pilot Study.

P < 0.05 in Validation.

P < 0.05 between Pilot and Validation.

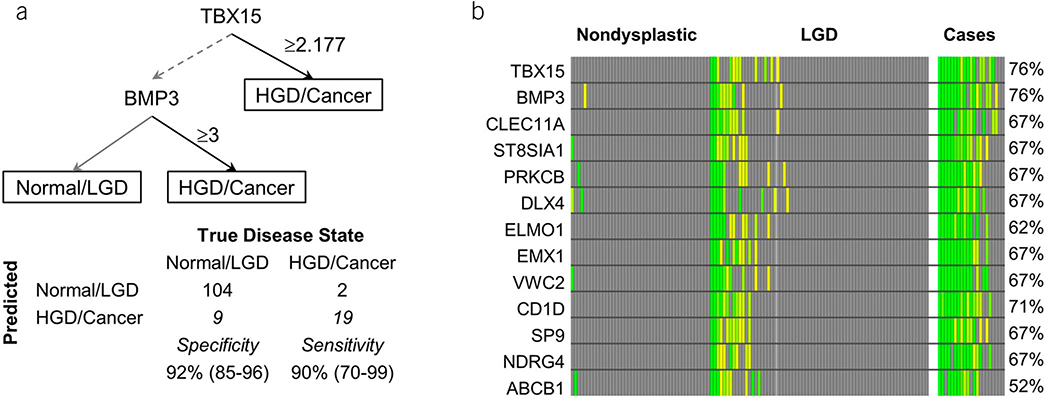

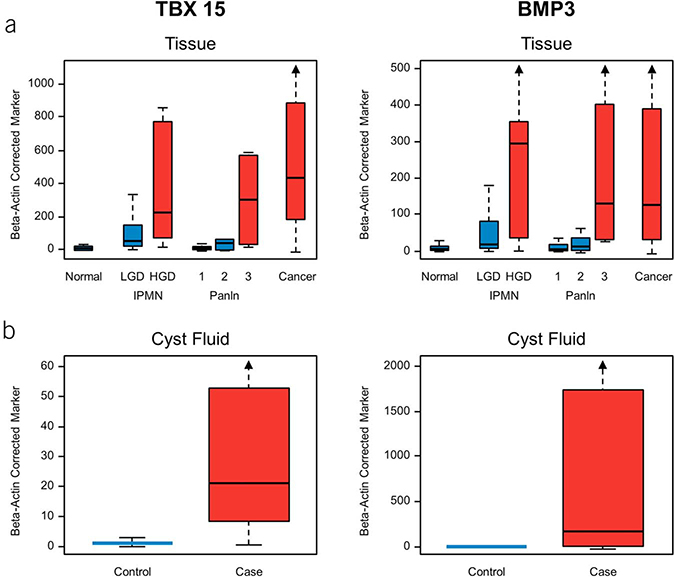

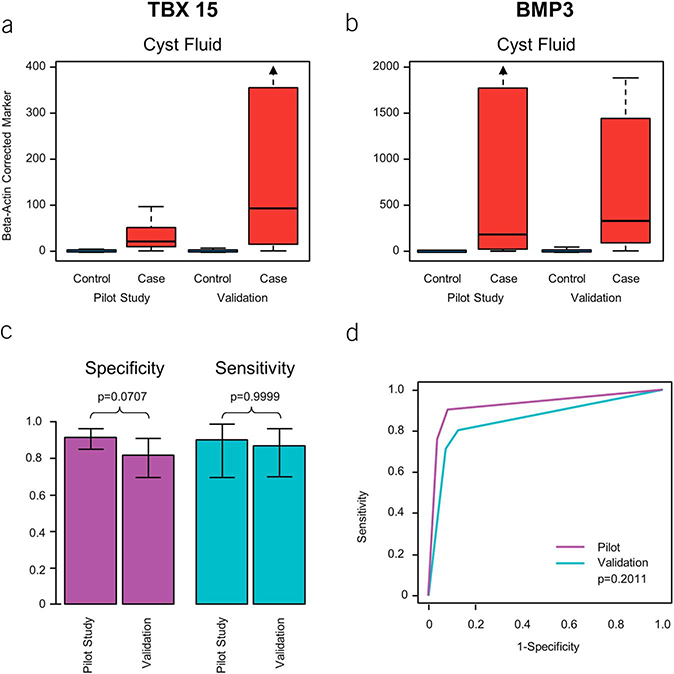

CF distributions of all 13 MDMs demonstrated evident separation between cases and controls (see Figure 1, Supplementary Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/AJG/A191) and incremental marker levels with advancing grades of dysplasia. Individual MDMs achieved AUCs ranging from 0.71 to 0.92 (see Table 3, Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/A190). rPart regression identified 2 MDMs (TBX15 and BMP3) that provided maximum separation between cases and controls (Figure 2a) and achieved an AUC of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.86–0.99) with a sensitivity of 90% (95% CI: 70%–99%) at a specificity of 92% (95% CI: 85%–96%). Methylated TBX15 and BMP3 individually demonstrated 76% sensitivity (95% CI: 53–92) at 90% specificity (95% CI: 83–95) and most false-positive findings occurring in controls with LGD as compared to those with ND (Figure 2b). CF and tissue distributions of methylated TBX15 and BMP3 (Figure 3) demonstrate significant fold change differences between cases and controls in tissue and CF. Relative ranking of all CF markers using random-forest regression further confirmed the highly informative nature of these top MDMs (see Figure 2, Supplementary Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/AJG/A192). The cross-validated AUC using the entire panel of 13 CF MDMs was 0.87 (95% CI: 0.76–0.99). Comparing the diagnostic performance of the 2-MDM panel in CF acquired surgically and endoscopically revealed no significant difference in sensitivity (88% vs 100%, P = 0.99) or specificity (92% vs 94%, P = 0.99). Although age and sex were significantly associated with case/control status, there was minimal effect with respect to these factors on the association of the MDMs with cases and controls (see Table 4, Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/A190), especially for TBX15 and BMP3.

Figure 2.

Discrimination of selected MDMs assayed from cyst fluid. (a) Decision tree classification with marker cutoffs using the top 2 markers TBX15 and BMP3. (b) Heat matrix for cyst fluid MDMs among cases and controls with sensitivity of individual MDMs at 90% specificity. The color ranges from yellow to green with “more green” indicating further distance from the specificity cutoff. HGD, harbor high-grade dysplasia; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; MDM, methylated DNA marker.

Figure 3.

Distributions of 2 discriminant methylated DNA markers in cases and controls. (a) Distributions in tissue by different grades of neoplasia from biological mucinous neoplasm. (b) Distributions in CF from cases (HGD or cancer) and controls (LGD or no dysplasia). CF, cyst fluid; HGD, harbor high-grade dysplasia; IPMN, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm; LGD, low-grade dysplasia.

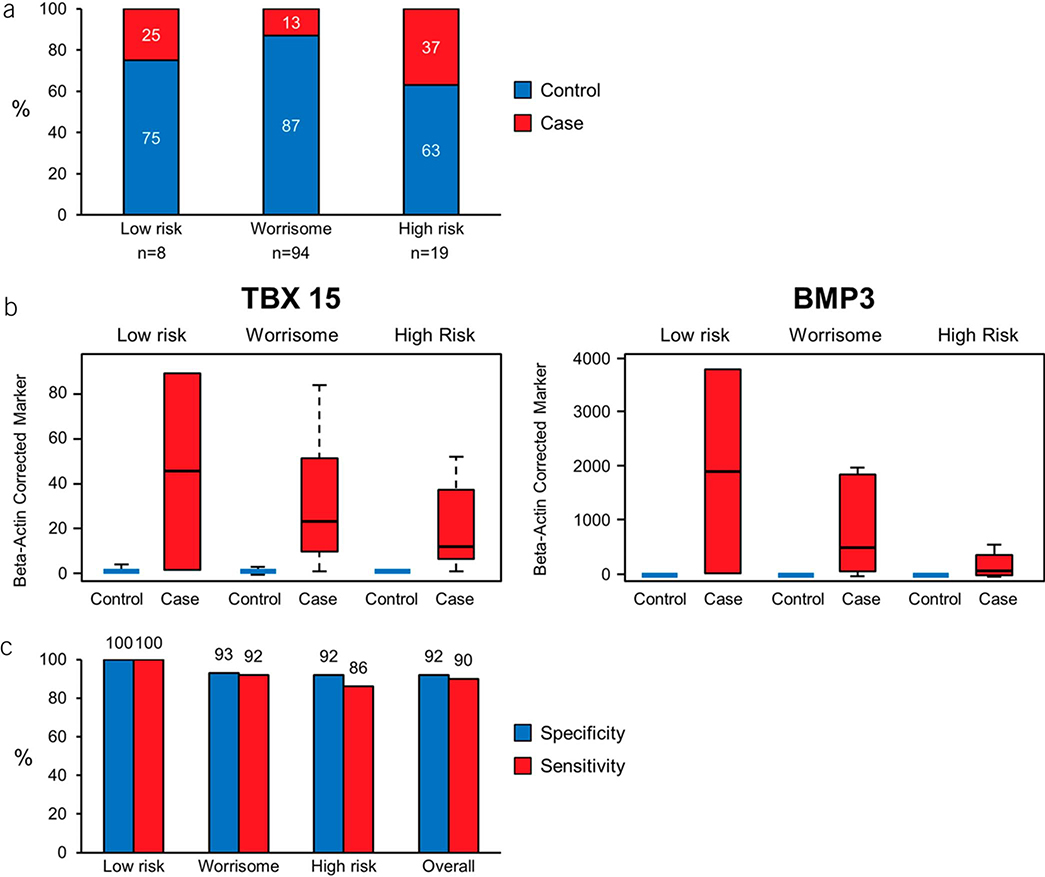

CF MDM performance within Fukuoka classification

Of the 134 CF samples included in the study, preoperative clinical and radiologic data sufficient for Fukuoka risk stratification were available in 121 cases, of which 94 had worrisome features (F-WR) and 19 were F-HR (Figure 4a). Prevalence of HGD/cancer in F-WR was 13% (12/94), and that in F-HR was 37% (7/19). There were 2 cases with HGD in the F-LR group. Distributions of the top 2 MDMs (TBX15 and BMP3) across the 3 Fukuoka risk strata demonstrated clear separation between cases and controls with high fold change (Figure 4b,c). This 2 MDM panel was 100% sensitive and specific for detecting advanced neoplasia in low-risk PCLs and achieved a sensitivity of 92% at a specificity of 93% for detecting advanced neoplasia in Fukuoka WR PCLs. This panel detected 6/7 (85%) cases with advanced neoplasia in the F-HR group with a specificity of 92% (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Findings in Fukuoka subsets. (a) Proportion of cases (HGD or cancer) and controls (LGD or no dysplasia) across the 3 Fukuoka risk groups. (b) Distributions of TBX15 and BMP3 across Fukuoka categories. (c) Sensitivity of the MDM panel at a specificity cutoff of 90% in the different Fukuoka risk groups. HGD, harbor high-grade dysplasia; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; MDM, methylated DNA marker.

Comparison with CF CEA and mutant KRAS

At 90% specificity, sensitivities of CF CEA and mutant KRAS for advanced neoplasia were 29% (95% CI: 11–52) and 48% (95% CI: 26–70), respectively. Case sensitivities were substantially and significantly better (P < 0.007) by both TBX15 and BMP3 individually and together as a panel than by mutant KRAS or CEA across the range of specifities, based on AUCs (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparative AUCs for TBX15, BMP3 (individually and in combination based on the predicted probability from rPart decision tree [indicated by asterisk]), mutant KRAS and cyst fluid CEA for distinguishing cases (HGD or cancer) and controls (LGD or no dysplasia). AUC, areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve; HGD, harbor high-grade dysplasia; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; rPart, regression partition tree.

Validation in CF

From an independent CF sample set of 87 pancreatic cysts (22 IPMN, 14 MCN, 12 serous cystadenoma, 21 cystic adenocarcinoma [16 IPMN, 5 indeterminate precursor], 10 HGD IPMN, and 8 inflammatory or other nondysplastic cysts), we categorized 31 as cases (10 HGD, 21 adenocarcinoma) and 56 as controls (20 ND, 36 LGD). Similar to results in the pilot phase, CF distributions of all 13 MDMs including the 2 MDMs in the panel demonstrated evident separation between cases and controls (Figure 6a–b). The cutoffs for the 2-marker panel (TBX 15, BMP3) identified on pilot testing were applied to the validation sample set, and at those pre-determined cutoffs, the sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of the 2-MDM panel in the validation cohort were 87% (95% CI: 70%–96%), 82% (70%–91%), and 0.86 (0.77–0.94), respectively (Figure 6c,d). Moreover, the pilot trained rPart and rForest trees had very similar diagnostic accuracy in the validation set (see Figure 3, Supplementary Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/AJG/A193).

Figure 6.

Comparative results of CF pilot and validation study. (a and b) CF distributions of TBX 15 and BMP 3 from cases (HGD or cancer) and controls (LGD or no dysplasia) in pilot study and subsequent validation. (c) Sensitivities and specificities of the 2-MDM panel. (d) AUCs for the 2-MDM panel in independent pilot and validation sets. AUC, areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CF, cyst fluid; HGD, harbor high-grade dysplasia; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; MDM, methylated DNA marker.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified and validated MDMs in pancreatic tissue that accurately discriminate high-grade precursor lesions and cancer (advanced neoplasia) from low-grade precursors and normal pancreas. We subsequently demonstrated that selected MDMs assayed from a small volume of CF detect advanced neoplasia with high sensitivity and specificity. In our direct comparison, the detection accuracy for advanced neoplasia by these novel MDMs was significantly better than by the currently available CF markers (CEA and mutant KRAS).

Unlike previous CF biomarker discovery efforts, the novel MDMs assayed in CF in this study were derived from a rigorous discovery effort aimed at detection of advanced neoplasia. We specifically identified highly informative MDMs that are acquired in the transition between LGD and HGD, which is critical for identification of advanced neoplasia. High discrimination was retained in subsequent translation to CF. The 2-marker MDM panel we describe is straight-forward to assay in CF, requires a very small CF volume, and achieves high-predictive accuracy. Although the MDMs we identified have not been previously described for such a diagnostic application, it is of biological interest to note that the functions of target genes aberrantly methylated relate to regulation of cell growth and transcription (see Table 5, Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/A190). TBX15 or T-box 15 is a transcription factor involved in cellular differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis. It has been shown to be associated with multiple cancers (24). BMP3 (bone morphogenic protein 3) is a member of the transforming growth factor-β growth factor superfamily and a putative tumor suppressor in colon cancer and other cancers, where it is downregulated via promoter hypermethylation (25,26).

In recent years, several studies have focused on molecular markers in CF, aiming to identify genetic alterations specific for PCL type and malignant potential. In one of the earliest studies in this field, the multicenter prospective PANDA study, the sequential combination of CF KRAS mutation followed by allelic loss was specific (96%) but had poor sensitivity (37%) for predicting advanced neoplasia (27). Although the utility of CF KRAS in differentiating mucinous from nonmucinous cysts was implicated in this study and validated in subsequent studies (28), the AUC for CF KRAS in our study was significantly lower compared with MDMs, providing further evidence that presence of mutant KRAS in CF is not a reliable predictor of advanced neoplasia. In a more recent multicenter retrospective study, Springer et al., (18) demonstrated that a combination of molecular and clinical markers was able to identify mucinous cysts with 90%–100% sensitivity and 92%–98% specificity. The investigators reported a complex molecular panel that included mutations in KRAS, GNAS, SMAD4, and TP53, loss of heterozygosity in chromosomal location of RNF43 and TP53, and aneuploidy in chromosome 5p, 8p, 13q, or 18q, and others identified patients requiring surgery (IPMNs with HGD/cancer, MCNs, and SPNs) with a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 92%. Several other genetic abnormalities have been identified in mucinous PCLs that have been implicated in neoplastic progression which include mutations in TP53, PIK3CA, PTEN, CDKN2A, and SMAD4 with increased CF telomerase activity (29–33). Singhi et al. (34) proposed an algorithmic approach using EUS-FNA and CF marker analysis for all cysts greater than 1.5 cm in size and concluded that cysts with a KRAS and/or GNAS mutation with either TP53 or PIK3CA/PTEN mutations should undergo surgical resection. In their study, 41 patients had surgical pathology, of which 13 harbored advanced neoplasia, and the proposed algorithm accurately identified 10 (77%) of these 13 cases. Other potential CF molecular markers include telomerase because telomerase activity correlated with the presence of HGD or cancer in resected worrisome cysts with a sensitivity of 73.7% and a specificity of 90.6% (33). More recently, a multi-institutional validation study using surgically collected CF reported concordance indexes of up to 0.8 for a panel of CF protein assays for discriminating high-risk from low-risk IPMNs (35). In their study, combining the protein marker panel with a clinical algorithm improved the highest discrimination (c-statistic 0.84). Sample viscosity was a limiting factor for the assay and resulted in elimination of 5 high-risk samples. Unlike our current study that included a wide range of cyst subtypes, this study included only pathologically confirmed IPMNs that would potentially limit the clinical application in the preoperative setting where the need for a predictive test is the greatest and cyst histopathologic subtype is not always evident. Another recent study reported results of a large panel of CF molecular markers tested in 59 IPMNs (36). Using single-platform PCR combining several promising CF biomarkers that included both mutant KRAS and GNAS in addition to multiple messenger RNA and micro-RNA targets, the authors reported a cross-validated AUC of 0.86 for differentiating high-risk from low-risk IPMNs (36). Validation in an independent sample set is more robust and is needed to further evaluate this approach.

We have found that epigenetic markers, due to inherent biological and technical advantages, achieve high accuracy for the detection of advanced neoplasia in multiple organs. It is now well-established in clinical practice that colorectal cancer and advanced precursor lesions can be accurately detected using a multitarget stool DNA test that includes MDMs (37–40). Furthermore, we have observed that an MDM panel alone assayed from stool detects cancer and HGD with high sensitivity and specificity from patients with inflammatory bowel disease based on early results (41,42). Recently published studies from our group have highlighted potential diagnostic applications of MDMs assayed from plasma in gastric, esophageal, and hepatocellular cancer detection (43–45). Premalignant lesions, such as Barrett’s esophagus (44) can be detected with high discrimination via nonendoscopic approaches using a sponge-on-string sampling device.

Hata, et al., (21) in a recent study, reported good discrimination for detecting advanced neoplasia using MDMs in pancreatic CF. They used existing candidate MDMs from previous studies to create a 7-marker panel (SOX17, BNIP3, FOXE1, PTCHD2, SLIT2, EYA4, and SFRP1). In their study, the best individual MDM (SOX17) had a sensitivity of 78.4% and a specificity of 85.6%. The 2-marker MDM panel in our study identified 90% of patients with advanced neoplasia at 92% specificity. Subsequent independent validation in a nonoverlapping set of CF samples using the same panel of methylated markers and with prespecified cutoffs derived from the discovery sample set has not been reported previously for CF MDMs and is a major strength of this current study. Moreover, although all 7 previously reported CF MDMs were sequenced in our discovery step, only BNIP3 and SOX17 met our a priori sequencing analysis criteria for selection as potential candidate MDMs. Neither of these markers met criteria prespecified for both technical and biological validation analyses. The other 5 MDMs (FOXE1, PTCHD2, SLIT2, EYA4, and SFRP1) were not identified as candidate markers by our pipeline for a variety of reasons that included elevated buffy coat methylation (PTCHD2), low methylation in tumor tissue (EYA4, FOXE1, SFRP1, and SLIT2), and nonsignificant P values in the regression analysis of sequencing data (FOXE1).

Currently, the greatest clinical dilemma in deciding between immediate surgery vs surveillance appears to be in the F-WR PCLs. A recent Mayo Clinic study showed that F-WR cysts possess a significantly lower 5-year PC risk compared with F-HR cysts (4.1% vs 49.7%; P < 0.001), and the cancer risk in the worrisome group was comparable to F-LR cysts (46). In a cohort of 281 patients with IPMNs managed nonoperatively, those with worrisome features had a 5-year disease-specific survival of 96%, suggesting that conservative management may be appropriate (47). In our study cohort of surgically resected cysts, the large majority (82/94; 87%) of F-WR cysts did not have advanced neoplasia. The high sensitivity and specificity for detecting advanced neoplasia in this large subset of F-WR cysts is promising and if validated in an unbiased prospective population of PCLs, has important clinical relevance because only a very small fraction of F-WR cysts that are surgically resected in current practice harbor advanced neoplasia.

Traditionally, surgical pathology has served as the criterion standard against which the performance of CF biomarkers has been assessed. However, it is important to mention that the cytologic grading of dysplasia in PCLs is subjective with poor interobserver agreement, and histologic grading is clinically often not feasible in the preoperative setting, given inherent challenges of pancreatic tissue acquisition (48). Furthermore, although some have proposed that the epithelial subtype of IPMNs is associated with differential risk of malignant transformation (49), recent studies have challenged the clinical utility of epithelial subtyping, suggesting that the concomitant presence of multiple epithelial subtypes is common and considerable number of IPMNs remain unclassifiable (50). Moreover, spontaneous cyst epithelial denudation can limit the histologic interpretation of cyst epithelial subtype and dysplasia grade (51). With further validation and optimization of assay techniques, it is possible that assay of molecular markers in CF will surpass or complement histology to more objectively, reproducibly, and accurately predict risk of malignant degeneration. The high discrimination we found for HGD and cancer by assay of the MDM panel could translate into improved effectiveness. As part of the assessment of this approach for future clinical implementation, it would be valuable to conduct a formal cost-effectiveness analysis using the appropriate input assumptions.

Our study has several limitations. First, this study was performed using archived CF samples; most of which had been collected at the time of surgery. MDM discrimination appeared similar or better when CF was collected via EUS before surgery, but endoscopic samples were relatively few in number. Furthermore, it is not yet known if similar discrimination would be present by MDM analysis in patients not meeting structural indications for surgery. Second, samples for this study were from archives of multiple centers, collected under different institutional protocols and were not balanced for potential confounders. This resulted in significant differences in baseline variables across groups, notably in age and gender. However, adjusted analyses did not demonstrate any significant influence of these clinical covariates on MDM performance. Because of this heterogeneity, the performance of the CF MDM panel in both the pilot and validation sets is more likely to be reproducible. Third, histologic diagnosis was not subjected to a centralized pathology review. Cases with intermediate grade dysplasia were reviewed by a single pathologist at our institution (T.C.S.) and reallocated to either LGD or HGD categories to conform to present classification guidelines. In addition, although surgical pathology provides the critically important diagnostic reference standard for assessing biomarker accuracy, it also potentially introduces verification bias or CF collection artifact that needs to be addressed in future prospective validation studies.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that novel DNA methylation markers assayed from CF can accurately detect advanced neoplasia in PCLs. Prospective studies are currently underway to include patients assigned to both immediate surgery and clinical follow-up arms in an attempt to corroborate these findings and optimize marker combinations for clinical use.

Supplementary Material

STUDY HIGHLIGHTS.

WHAT IS KNOWN

Pancreatic cysts are common, a subset can progress to cancer. Cysts containing high-grade dysplasia or cancer cells should be surgically resected. Algorithms to identify patients at risk for advanced neoplasia in pancreatic cysts are not accurate.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

In an analysis of pancreatic tissue and cyst fluid samples, we identified and validated DNA methylation makers that can detect advanced neoplasia.

A panel of two methylated DNA markers (TBX 15, BMP3) discovered and validated in tissue and subsequently validated in cyst fluid assays is highly sensitive and specific for differentiating cysts with no dysplasia or low-grade dysplasia from those with advanced neoplasia.

Further rigorous validation of these cyst fluid methylated DNA markers in prospective studies is indicated

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Preliminary data from this investigation were presented at Digestive Disease Week 2016 and 2017 and the American College of Gastroenterology Annual Meeting 2017. The authors thank Terri Johnson for her outstanding clerical assistance throughout the study and manuscript submission.

Financial support: Funding was provided by the Carol M. Gatton Foundation (to DAA). Research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Institute of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30DK084567. The project described was also supported by Award Number P50 CA102701 (Mayo Clinic SPORE in Pancreatic Cancer) and R37CA214679 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. Exact Sciences (Madison WI) provided funds for sequencing and critical assay reagents.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: David A. Ahlquist, MD.

Potential competing interests: Mayo Clinic has licensed intellectual property to Exact Sciences on molecular markers and sample processing techniques for multiple cancers and precancers, including pancreatic cancer. As co-inventors on licensed technologies, several co-authors (D.A.A., J.B.K., S.M., W.R.T., D.W.M., and T.C.Y.) could share potential future royalties to Mayo Clinic from Exact Sciences in accordance with institutional policy and oversight. G.P.L. and H.T.A. are Exact Sciences employees. Exact Sciences provided assay materials and partial funding but had no role in the protocol design, study execution, or analysis of data. The other authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to declare.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL accompanies this paper at http://links.lww.com/AJG/A190, http://links.lww.com/AJG/A191, http://links.lww.com/AJG/A192, http://links.lww.com/AJG/A193

REFERENCES

- 1.Moris M, Bridges MD, Pooley RA, et al. Association between advances in high-resolution cross-section imaging technologies and increase in prevalence of pancreatic cysts from 2005 to 2014. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:585–93.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee KS, Sekhar A, Rofsky NM, et al. Prevalence of incidental pancreatic cysts in the adult population on MR imaging. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105:2079–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Jong K, Nio CY, Hermans JJ, et al. High prevalence of pancreatic cysts detected by screening magnetic resonance imaging examinations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:806–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheiman JM, Hwang JH, Moayyedi P. American gastroenterological association technical review on the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology 2015;148: 824–48.e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tada M, Kawabe T, Arizumi M, et al. Pancreatic cancer in patients with pancreatic cystic lesions: A prospective study in 197 patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:1265–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi SH, Park SH, Kim KW, et al. Progression of unresected intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas to cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15: 1509–20.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crippa S, Capurso G, Cammà C, et al. Risk of pancreatic malignancy and` mortality in branch-duct IPMNs undergoing surveillance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis 2016;48:473–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka M, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Adsay V, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology 2012;12:183–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka M, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Kamisawa T, et al. Revisions of international consensus Fukuoka guidelines for the management of IPMN of the pancreas. Pancreatology 2017;17:738–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vege SS, Ziring B, Jain R, et al. American gastroenterological association institute guideline on the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology 2015;148:819–22; quize12–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas. European evidence-based guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Gut 2018;67: 789–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaimakliotis P, Riff B, Pourmand K, et al. Sendai and Fukuoka consensus guidelines identify advanced neoplasia in patients with suspected mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:1808–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee A, Kadiyala V, Lee LS. Evaluation of AGA and Fukuoka Guidelines for EUS and surgical resection of incidental pancreatic cysts. Endosc Int Open 2017;5:E116–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge PS, Muthusamy VR, Gaddam S, et al. Evaluation of the 2015 AGA guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms in a large surgically confirmed multicenter cohort. Endosc Int Open 2017;5:E201–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woolf KM, Liang H, Sletten ZJ, et al. False-negative rate of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for pancreatic solid and cystic lesions with matched surgical resections as the gold standard: One institution’s experience. Cancer Cytopathol 2013;121:449–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cizginer S, Turner BG, Turner B, et al. Cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen is an accurate diagnostic marker of pancreatic mucinous cysts. Pancreas 2011;40:1024–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singhi AD, Nikiforova MN, Fasanella KE, et al. Preoperative GNAS and KRAS testing in the diagnosis of pancreatic mucinous cysts. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:4381–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Springer S, Wang Y, Dal Molin M, et al. A combination of molecular markers and clinical features improve the classification of pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1501–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong SM, Kelly D, Griffith M, et al. Multiple genes are hypermethylated in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Mod Pathol 2008;21:1499–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kisiel JB, Raimondo M, Taylor WR, et al. New DNA methylation markers for pancreatic cancer: Discovery, tissue validation, and pilot testing in pancreatic juice. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:4473–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hata T, Dal Molin M, Hong SM, et al. Predicting the grade of dysplasia of pancreatic cystic neoplasms using cyst fluid DNA methylation markers. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:3935–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu H, Smith ZD, Bock C, et al. Preparation of reduced representation bisulfite sequencing libraries for genome-scale DNA methylation profiling. Nat Protoc 2011;6:468–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun Z, Baheti S, Middha S, et al. SAAP-RRBS: Streamlined analysis and annotation pipeline for reduced representation bisulfite sequencing. Bioinformatics 2012;28:2180–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papaioannou VE. The T-box gene family:Emerging roles in development, stem cells and cancer. Development 2014;141:3819–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loh K, Chia JA, Greco S, et al. Bone morphogenic protein 3 inactivation is an early and frequent event in colorectal cancer development. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2008;47:449–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kisiel JB, Li J, Zou H, et al. Methylated bone morphogenetic protein 3 (BMP3) gene: Evaluation of tumor suppressor function and biomarker potential in biliary cancer. J Mol Biomark Diagn 2013;4:1000145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khalid A, Zahid M, Finkelstein SD, et al. Pancreatic cyst fluid DNA analysis in evaluating pancreatic cysts: A report of the PANDA study. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69:1095–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikiforova MN, Khalid A, Fasanella KE, et al. Integration of KRAS testing in the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions: A clinical experience of 618 pancreatic cysts. Mod Pathol 2013;26:1478–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanda M, Sadakari Y, Borges M, et al. Mutant TP53 in duodenal samples of pancreatic juice from patients with pancreatic cancer or high-grade dysplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:719–30 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Carracedo D, Turk AT, Fine SA, et al. Loss of PTEN expression is associated with poor prognosis in patients with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19: 6830–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sasaki S, Yamamoto H, Kaneto H, et al. Differential roles of alterations of p53, p16, and SMAD4 expression in the progression of intraductal papillary-mucinous tumors of the pancreas. Oncol Rep 2003;10:21–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biankin AV, Biankin SA, Kench JG, et al. Aberrant p16(INK4A) and DPC4/Smad4 expression in intraductal papillary mucinous tumours of the pancreas is associated with invasive ductal adenocarcinoma. Gut 2002; 50:861–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hata T, Dal Molin M, Suenaga M, et al. Cyst fluid telomerase activity predicts the histologic grade of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:5141–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singhi AD, Zeh HJ, Brand RE, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Guidelines are inaccurate in detecting pancreatic cysts with advanced neoplasia: A clinicopathologic study of 225 patients with supporting molecular data. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:1107–17.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al Efishat MA, Attiyeh MA, Eaton AA, et al. Multi-institutional validation study of pancreatic cyst fluid protein analysis for prediction of high-risk intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Ann Surg 2018;268:340–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maker AV, Hu V, Kadkol SS, et al. Cyst fluid biosignature to predict intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas with high malignant potential. J Am Coll Surg 2019;228:721–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Redwood DG, Asay ED, Blake ID, et al. Stool DNA testing for screening detection of colorectal neoplasia in Alaska native people. Mayo Clin Proc 2016;91:61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahlquist DA, Zou H, Domanico M, et al. Next-generation stool DNA test accurately detects colorectal cancer and large adenomas. Gastroenterology 2012;142:248–56; quiz e25–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lidgard GP, Domanico MJ, Bruinsma JJ, et al. Clinical performance of an automated stool DNA assay for detection of colorectal neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:1313–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 2014;370: 1287–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kisiel JB, Yab TC, Nazer Hussain FT, et al. Stool DNA testing for the detection of colorectal neoplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:546–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kisiel JB, Klepp P, Allawi HT, et al. Analysis of DNA methylation at specific loci in stool samples detects colorectal cancer and high-grade dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:914–21.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson BW, Suh YS, Choi B, et al. Detection of gastric cancer with novel methylated DNA markers: Discovery, tissue validation, and pilot testing in plasma. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:5724–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iyer PG, Taylor WR, Johnson ML, et al. Highly discriminant methylated DNA markers for the non-endoscopic detection of barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:1156–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kisiel JB, Dukek BA, VSRK R, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma detection by plasma methylated DNA: Discovery, phase I pilot, and phase II clinical validation. Hepatology 2019;69:1180–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mukewar S, de Pretis N, Aryal-Khanal A, et al. Fukuoka criteria accurately predict risk for adverse outcomes during follow-up of pancreatic cysts presumed to be intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Gut 2017;66: 1811–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crippa S, Bassi C, Salvia R, et al. Low progression of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms with worrisome features and high-risk stigmata undergoing non-operative management: A mid-term follow-up analysis. Gut 2017;66:495–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goyal A, Abdul-Karim FW, Yang B, et al. Interobserver agreement in the cytologic grading of atypia in neoplastic pancreatic mucinous cysts with the 2-tiered approach. Cancer Cytopathol 2016;124:909–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mino-Kenudson M, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Baba Y, et al. Prognosis of invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm depends on histological and precursor epithelial subtypes. Gut 2011;60:1712–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schaberg KB, DiMaio MA, Longacre TA. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms often contain epithelium from multiple subtypes and/or are unclassifiable. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gómez V, Majumder S, Smyrk TC, et al. Pancreatic cyst epitheliaĺ denudation: A natural phenomenon in the absence of treatment. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;84:788–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.