Abstract

Persons with Alzheimer’s disease often experience problems finding their way (wayfinding) even in familiar locations. One possible explanation for wayfinding impairments in persons with AD is that they use different wayfinding strategies than those without the disease; and these strategies may be more ineffective. This study examined differences in wayfinding strategies and spatial anxiety in older adults with and without early-stage AD, as well as gender’s effect on both variables. Cognitively normal older adults (N=50) and adults with early stage AD (N=38) completed a demographic survey, cognitive tests, the Wayfinding Strategies Scale, and the Spatial Anxiety Scale. Results indicated that cognitively normal adults used significantly more orientation strategies [t(85)=2.536, p=.013] than did AD adults, and males (N=37) used significantly more orientation strategies than did females [N=51; t(85)=2.413, p=.018]. Subjects with AD rated their spatial anxiety significantly higher than cognitively normal adults [N=51; t(84)=−3.89, p<.001]. Orientation strategy use was inversely related to spatial anxiety (r=−.434, p<.001). These findings suggest that persons with early-stage AD may use fewer wayfinding strategies and have higher wayfinding-related anxiety compared to adults without AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, aging, wayfinding, anxiety

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive, debilitating illness affecting an estimated 5.8 million Americans (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019). One major debilitating factor for persons with AD is impaired wayfinding. Wayfinding is the ability to find one’s way in an environment, typically with the goal of reaching a particular destination in an expedient manner (Passini, Pigot, Rainville, & Tetreault, 2000). It is estimated that at least 40–50% of persons with early-stage AD have wayfinding difficulties in both familiar and unfamiliar environments, making this difficulty one of the most prevalent and problematic disease symptoms (Pai & Jacobs, 2004). With over 500,000 new AD cases diagnosed each year (BrightFocus Foundation, 2019), the number of older adults experiencing impaired wayfinding will continue to grow. This is a significant issue because wayfinding ability is essential for autonomous functioning, including independence in toileting, eating, and socialization. Impaired wayfinding ability can cause psychological responses such as anxiety, insecurity, and agitation, as well as physical safety concerns such as increased risk for falls and getting lost in unfamiliar environments (Caspi, 2014; Chiu et al., 2004). Persons with AD can experience spatial anxiety or a feeling of apprehension related to wayfinding tasks (e.g., fear or worry about navigating unfamiliar surroundings; Hund & Minarik, 2006; Lawton, 1994). Finally, persons with wayfinding problems can be severely harmed or even die from getting lost in the community (Rowe & Bennett, 2003).

Background

Wayfinding Strategies

Wayfinding is a complex process involving multiple cognitive functions that decline with normal aging and more significantly with cognitive disease (Allison, Fagan, Morris, & Head, 2016; Benke, Karner, Petermichl, Prantner, & Kemmler, 2014; Harris & Wolbers, 2014; Head & Isom; 2010). While wayfinding in a new or unfamiliar environment, people often use a route strategy, in which they follow a series of steps to reach a goal destination (Allison et al. 2016; Lawton, 1994). Individuals who use route strategies must be able to follow marked signs, recognize landmarks, or adhere to written or verbal sets of directions. An example of route strategy would be to “turn left at the first stop sign and then take the second driveway on the left.” Route strategies are somewhat inflexible due to their rigidity and reliance on sequential directions (Lawton, 1994).

As people become more familiar with an environment, they may develop a cognitive map or enduring memory of the environment based on the spatial relationships among the environmental information present, such as landmarks and paths (Iaria, Palermo, Committeri, & Barton, 2009). Orientation strategies, which are those that use cognitive maps, more flexible navigation than route strategies and allow for route adjustments, such as short-cuts, when needed (Lawton, 1994). Often, a person will switch back and forth between orientation and route strategies in order to successfully complete a wayfinding task (Harris & Wolbers, 2014).

Impaired Wayfinding in Older Adults

Multiple studies in real world and virtual environments have shown older adults have impaired wayfinding abilities compared to their younger counterparts (Benke et al., 2014; Harris & Wolbers, 2014). For example, older adults take more time to learn a route and use fewer shortcuts (Harris & Wolbers, 2014), as well as make more errors and stops during a wayfinding task (Taillade et al., 2013). Head and Isom (2010) found that older adults completing a wayfinding task in a virtual environment were less able to recall landmarks and point them out on a virtual map. They also were less likely to complete the route successfully as the number of navigational arrows decreased.Wayfinding deficits in aging may be due to a decline in the ability to use orientation strategies (Gazova et al., 2013; Moffat, Elkins, & Resnick, 2006; Rodgers, Sindone III, & Moffat, 2012), caused by age-related hippocampal changes (Colombo et al., 2017). Several studies have shown overwhelmingly that older adults use route-based strategies more often than orientation strategies (Moffat et al., 2006; Rodgers et al., 2012).

Wayfinding Strategies in Alzheimer’s Disease

Despite the growing body of knowledge related to wayfinding in older adults, less is known about the wayfinding abilities and strategies of person with AD. Although evidence is limited, person with AD have a reduced ability to employ both route and orientation strategies compared to healthy older adults (Allison et al., 2016). While persons with AD can form cognitive maps, they often require more time in an environment to do so (Allison et al., 2016). They also have more difficulty recalling landmarks, affecting route and orientation strategy use (Benke et al., 2014). Additionally, persons with AD can have difficulty maintaining directed attention, making them less able to focus on environmental information (Chiu et al., 2004). Finally, the ability to switch back and forth between route and orientation strategies may be reduced in persons with early stage AD as it may be in older adults without disease (Harris & Wolbers, 2014).

Gender-related Wayfinding Abilities and Strategies in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease

The factor of gender has been to wayfinding ability. Males have been shown to find their way faster and more effectively than women do in many kinds of spatial navigation tests (Boone, Gong, & Hegarty, 2018; Davis & Therrien, 2012). The differences in wayfinding between males and females are related to several factors. One of the more studied differences between males and females is variation in spatial strategy use. On a self-reported Wayfinding Strategies Scale, healthy young females scored higher on route strategies and lower on orientation strategies (WSS; Lawton, 1994; Lawton & Kallai, 2002). In a qualitative study where older males and females were asked to describe the strategies they used in a virtual reality maze task, cognitively normal females reported using fewer strategies after initial learning (Davis & Weisbeck, 2015).

Spatial Anxiety

Some researchers have related the female disadvantage in spatial-task performance to spatial anxiety, a feeling of uneasiness related to wayfinding tasks (Hund & Minarik, 2006; Lawton, 1994). High spatial anxiety levels have been correlated with wayfinding errors and increased time to reach a destination (Hund & Minarik, 2006). Spatial anxiety has been shown to be more common in women than in men, and is more likely to occur in those who use route versus orientation strategies (Lawton, 1994; Lawton & Kallai, 2002). Spatial anxiety also may be related to hippocampal activity (Engin & Treit, 2007), as persons with hippocampal atrophy (often found in AD) have significantly increased spatial anxiety (Kremmyda et al., 2016). Lawton (1994) found persons who used orientation strategies were less likely to experience spatial anxiety than those using route strategies.

To date, there is no research examining spatial anxiety in older persons or persons with AD. One large study showed that approximately 20% of older adults reported mild, moderate, or severe levels of anxiety related to the highly spatial task of driving (Taylor, Alpass, Stephens, & Towers, 2010). However, it is unknown whether AD-related cognitive deficits make people more or less likely to experience spatial anxiety. Persons with AD may not experience spatial anxiety because they overestimate their cognitive abilities (known as anosognosia; Perrotin et al., 2015). Alternatively, individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) may be aware of their abilities, causing them anxiety about complex spatial tasks (Piras, Piras, Orfei, Caltagirone, & Spalletta, 2016). Beginning evidence shows that general anxiety is common in individuals with dementia, therefore persons with AD may have anxiety about any complex task, including spatial tasks (Seignourel, Kunik, Snow, Wilson, & Stanley, 2008). Since anxiety is correlated with decreased quality of life in persons with dementia (Seignourel et al., 2008), further research is needed to determine the prevalence of wayfinding-related spatial anxiety in adults with early-stage AD.

Purpose

Despite the growing body of research on wayfinding ability in humans, there is a paucity of research on wayfinding strategy use and spatial anxiety in older persons with AD, as well as gender’s effect on these variables. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine

differences in wayfinding strategies and spatial anxiety between older adults with and without early-stage AD;

gender effects on the use of wayfinding strategies and anxiety in this population; and

relationships among cognitive measures and spatial strategies and anxiety.

Based on the literature review, the hypotheses were older persons with AD would have decreased orientation strategies and higher spatial anxiety scores compared to controls; males in both groups would have higher orientation strategies than females; and females in both groups would report higher spatial anxiety. Finally, we wanted to explore relationships among cognitive variables, wayfinding strategy use, and spatial anxiety.

Methods

Participants

This study is part of a larger study in which wayfinding was assessed in older adults without cognitive impairment and those with early-stage AD (blinded for review). In the parent study, a control group of 50 community-dwelling older adults without cognitive disease was recruited using newsletters, announcements, and flyers. Participants with AD (N=38) were recruited from memory clinics and AD support groups. To be in the study, participants had to be 62 years of age or older, and without a history of neurologic or cognitive disorders (other than AD for the AD group). To ensure individuals could see to navigate, they needed a visual acuity of 20/40 with correction and could not have color blindness. The control group had to demonstrate cognitive ability within the normal range according to the Mini Mental Status Test (a score of 27 or higher; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975). Persons in the AD group had to have a physician’s diagnosis of AD or mild cognitive impairment due to AD and had to score within early-stage AD—.5 (questionable) or 1 (mild)—on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR; Hughes, Berg, Danziger, Coben, & Martin, 1982). A descriptive correlational design was used to determine differences in wayfinding strategies and spatial anxiety between the control group and individuals with AD, as well as correlations among cognitive tests, wayfinding strategies, and spatial anxiety.

Procedures

The University’s and affiliated hospital’s Institutional Review Boards approved the study. Study personnel discussed the study with potential participants and then met with them in their homes or at the University lab. For participants with AD, study personnel also contacted their legally authorized representatives (LARs) or decision makers (with the participant’s permission) and asked them to attend the first meeting.

At the first meeting, the study was explained to the participants and LARs. Participants with AD then completed the Evaluation to Sign Consent (ESC) measure to determine consent capacity (Resnick et al., 2007). For those who did not exhibit consent capacity, the decision maker gave consent, and the participants gave assent to participate. Participants then were asked to complete the surveys described in the Measures section.

Measures

Participants completed an investigator-designed demographics survey to document their age, existing medical conditions, living situation, marital status, and socioeconomic status.

Cognitive measures.

Cognition was assessed with the 30-item Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA; Nasreddine et al., 2005), which measures memory, visuospatial ability, attention, concentration, working memory, language, calculation, orientation, and verbal language. The MoCA has documented sensitivity in identifying MCI (83%) and mild dementia (94–100%; Nasreddine et al., 2005; Smith, Gildeh, & Holmes, 2007).

Digit Span tests were administered to assess working memory and attention (Weschler, 1987). In the Digit Span Forwards (DSF) test, researchers ask participants to repeat a gradually increasing series of numbers until a series is missed twice. For Digit Span Backwards (DSB) test, participants must repeat the series in reverse order. Those with better working memory and attention can repeat longer series of numbers. Lezak (1995) reported that the normal score for the DSF is ≥5 and for the DSB is ≥4. These measures were included because they have been shown to influence spatial tasks in other studies.

Wayfinding strategies.

The Wayfinding Strategies Scale International (WSS) was used to measure route and orientation strategy use (Lawton, 1994; Lawton & Kallai, 2002). In this instrument, participants are asked to rate how likely they are to use certain strategies when walking, driving, or riding a bike through a somewhat familiar town and trying to find their way in a large building or complex they have not visited before. Likert-scale responses ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (almost always). The 11 orientation-strategy questions asked respondents to perform such tasks as visualizing an area’s map or layout and keeping track of direction. The six route-strategy questions asked respondents to give directions (e.g., how many streets to pass before making a turn).

A WSS factor analysis revealed two factors: route and orientation strategies (Lawton & Kallai, 2002). The WSS’s predictive validity has been documented by several studies relating orientation strategy subscale scores to a sense of direction and wayfinding ability (Hund & Minarik, 2006; Lawton & Kallai, 2002). Because this tool has been tested only on young adults—never in an older adult population—a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted in MPlus (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) using Lawton and Kallai’s (2002) two-factor model. The initial model did not have a good fit. A subsequent exploratory factor analysis resulted in a two-factor solution with three questions removed due to poor loading on either factor or cross loading. The final model was comprised of two factors: nine items (alpha .85) for the orientation strategy factor and five (alpha .82) for the route strategy factor. Table 1 shows the factor loadings for each subscale’s items. The questions loading on one of the two factors were consistent with prior research on the tool (Lawton & Kallai, 2002).

Table 1.

Factor Loadings for the Wayfinding Strategy Scale

| Items | Factor I |

Factor II |

|---|---|---|

| I visualized a map or layout of the area in my mind as I went. | .62 | .16 |

| I kept track of the direction (north, south, east, or west) in which I was going. | .75 | −.01 |

| I kept track of where I was in relation to the sun (or moon) in the sky as I went. | .68 | .001 |

| As I went, I made a mental note of the distance I traveled on different roads. | .68 | .32 |

| I kept track of where I was in relation to a reference point, such as the center of town, lake, river, or mountain. | .60 | .33 |

| I could visualize what was outside of the building or complex in the direction I was heading inside the building. | .68 | .06 |

| I always kept in mind the direction from which I had entered the building or complex (e.g. north, east, south, or west side of the building). | .62 | −.05 |

| Whenever I made a turn, I knew which direction I was facing. | .67 | −13 |

| I thought of my location in the building or complex in terms of north, south, east, and west. | .62 | −.03 |

| I asked for directions telling me how many streets to pass before making each turn. | .−.001 | .73 |

| I asked for directions telling me whether to turn right or left at particular streets or landmarks. | −.02 | .84 |

| I appreciated the availability of someone (e.g., a receptionist) who could give me directions. | −.16 | .80 |

| Clearly visible signs pointing the way to different sections of the building or complex were important to me. | .01 | .88 |

| Clearly labeled room numbers and signs identifying parts of the building or complex were very helpful in finding my way. | .12 | .79 |

Note. Model Fit information: RMSEA=.141 [CI .118, .165], with a CFI of .884, and a TLI of .835.

For this study, each subscale’s item total (after the three questions were removed) determined the overall rating for orientation and route strategy use. The scores ranged from 9–45 for the orientation subscale and 5–25 for the route subscale, with higher scores indicating more use of that subscale’s strategy.

Spatial anxiety.

Lawton’s Spatial Anxiety Scale (Lawton, 1994; Lawton & Kallai, 2002) was used to assess self-rated anxiety about wayfinding tasks in an unfamiliar town or city. The scale includes eight Likert-scale items, with responses ranging from “not at all anxious” to “very anxious.” Using principle component analysis, the researchers identified an alpha coefficient of .87, with all items loading on one factor.

Since this tool has not been used in an older adult population, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted in Mplus (Muthen & Muthen, 2017). All eight items loaded on one factor (alpha coefficient .91; Table 2). The sum of the eight items reflects an overall wayfinding anxiety score ranging from 8–64 points, with higher scores indicating higher anxiety.

Table 2.

Factor Loadings for Spatial Anxiety Scale

| Question | Factor Loading |

|---|---|

| Deciding which direction to walk in an unfamiliar city or town after coming out of a train/bus/metro station or parking garage. | .86 |

| Finding my way to an appointment in an unfamiliar area of a city or town. | .82 |

| Leaving a store that I have been to for the first time and deciding which way to turn to get to a destination. | .88 |

| Finding my way back to a familiar area after realizing I have made a wrong turn and become lost while traveling. | .83 |

| Finding my way in an unfamiliar shopping mall, medical center, or large building complex. | .52 |

| Finding my way out of a complex arrangement of offices that I have visited for the first time. | .87 |

| Trying a new route that I think will be a shortcut, without a map. | .82 |

| Pointing in the direction of a place outside that someone wants to get to and has asked for directions, when I am in a windowless room. | .90 |

Note. N=98

Results

Sample

The study had 88 participants (50 in the control group and 38 in the AD group), ranging from 62 to 92 years of age (mean age 76.24 years). The sample was 42% male and 58% female and most participants were Caucasian (96.5%). There were no significant differences between the groups in age, race, gender, years of education, marital status, financial status, or number of medications. There also were no significant differences between groups in DSF or DSB performance. Control group participants were more likely to live alone than AD participants (Table 3). As expected, AD group participants scored significantly lower on the MMSE and MoCA than did control group participants.

Table 3.

Comparison of demographic and cognitive variables between study groups

| Demographic Variables |

Control Group (n=50) |

AD Group (n=38) |

t (df) | Chi square (df) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SD) Range |

75.46 (5.254) 62 – 86 |

77.26 (6.729) 63 – 92 |

−1.412 (86) | 0.162 | |

| Years education (M, SD) Range |

16.05 (2.752) 20 – 22 |

15.47 (3.211) 12 – 24 |

0.905 (86) | 0.368 | |

| Female (n, %) | 32 (64%) | 19 (50%) | 1.737 (1) | 0.188 | |

| White (n, %) | 47 (94%) | 38 (100%) | 2.360 (1) | 0.124 | |

| Single (n, %) | 18 (36%) | 7 (18.4%) | 3.281 (1) | 0.070 | |

| Lives alone (n, %) | 17 (34%) | 3 (7.9%) | 11.488 (3) | 0.009 | |

| Has financial needs (n, %) | 2 (4%) | 3 (7.9%) | 0.697 (2) | 0.706 | |

| Number of Medications (M, SD) Range |

6.82 (4.552) 0 – 20 |

6.13 (3.543) 0 – 16 |

0.771 (86) | 0.443 | |

| DSF (M, SD) Range |

6.12 (0.961) 5 – 8 |

5.97 (1.093) 4 – 8 |

0.665 (85) | 0.508 | |

| DSB (M, SD) Range |

4.50 (1.182) 2 – 7 |

4.14 (1.159) 2 – 7 |

1.435 (85) | 0.155 | |

| MMSE (M, SD) Range |

29.16 (0.997) 27 – 30 |

25.87 (3.006) 19 – 30 |

6.484 (43.219) | < 0.001 | |

| Snellen Eye Test (M, SD) Range |

27.06 (7.963) 15 – 40 |

28.16 (8.254) 15 – 40 |

−0.631 (86) | 0.530 | |

| MoCA Total Score (M, SD) Ramge |

25.64 (2.097) 20 – 30 |

18.97 (3.578) 12 – 26 |

10.120 (54.061) | < 0.001 |

Note. AD=Alzheimer’s disease; DSF=Digit Span Forward; DSB=Digit Span Backward; MMSE=Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA=Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

Wayfinding Strategy Use

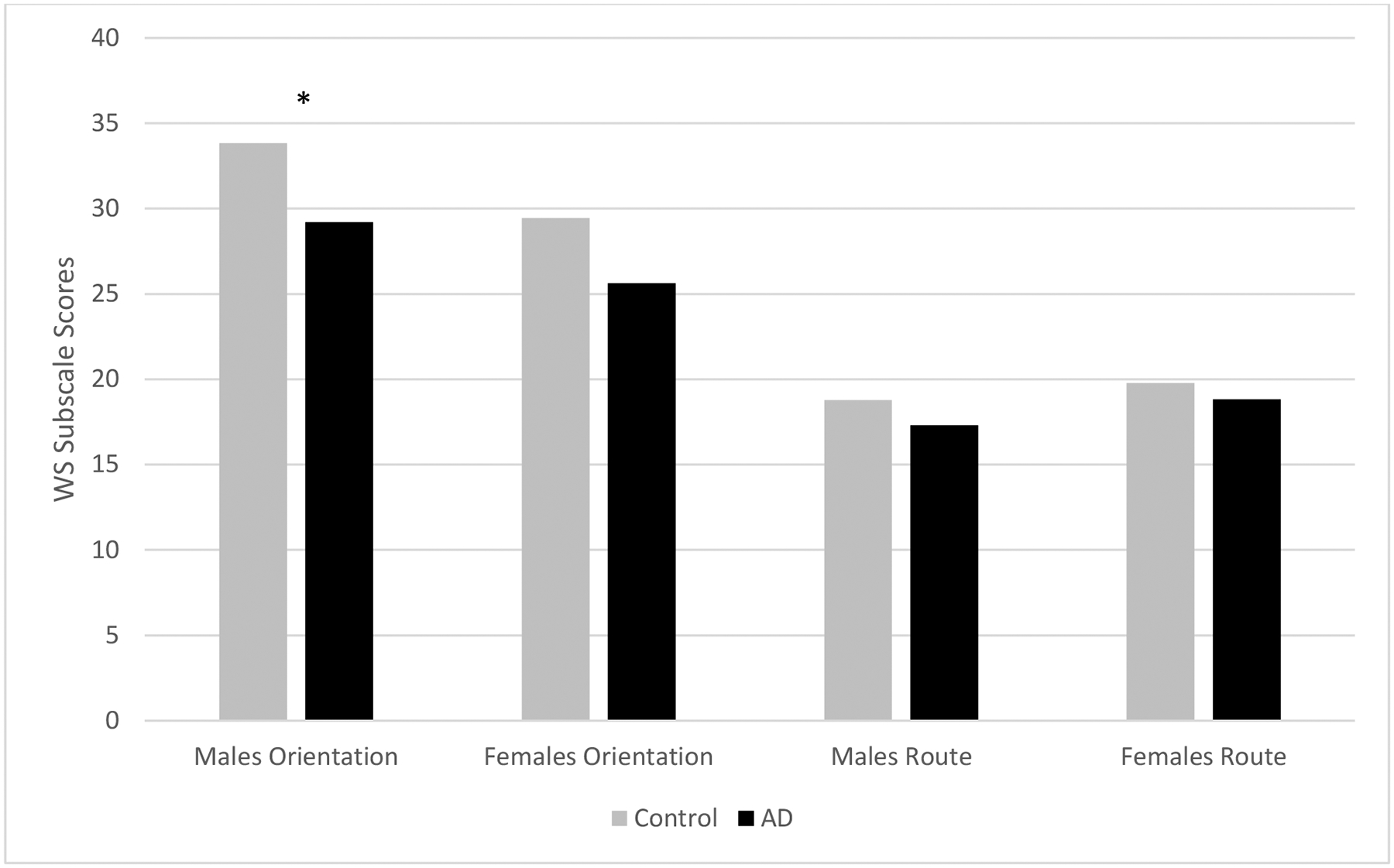

WSS scores ranged from 12–42 (M=29.51, SD=6.68) for orientation strategies and 9–25 (M=18.14, SD=3.35) for route strategies. Overall, control group participants scored significantly higher (M=31.02, SD=6.93) in orientation strategy use than did the AD participants (M=27.46, SD=5.81) as hypothesized [t(85)=2.54, p=.013]. Males also reported using significantly more orientation strategies (M=31.46, SD=6.20) than females (M=28.06, SD=6.71) as hypothesized [t(85)=2.41, p=.018]. There was a trend for females to score higher in route strategies (M=19.44, SD=3.39) than males (M=18.03, SD=3.15; t(85)=−1.98, p=.051). Control group males scored significantly higher on orientation strategies than did AD group males. Likewise, control group females scored higher on orientation strategies than did AD group females. There were no significant differences in route strategy scores for males or females in the control group compared to the AD group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Gender differences in wayfinding strategies between groups. Males’ and females’ orientation and route strategy scores were compared between the AD and control groups. This graph shows that males in the control group scored significantly higher in the reporting of orientation strategies than did males in the AD group (t(35)=2.415, p=.021). There was as trend for females in the control group to score higher in orientation strategies than those in the AD group (t(48)=1.994, p=.052). There was no significant difference in route strategy use in males or females between groups.

* p<.05.

Spatial Anxiety

The spatial anxiety scores (SAS) ranged from 8–34 (M=16.78, SD=6.07) for the whole group. As hypothesized, AD participants scored significantly higher on the SAS (M=19.56, SD=6.064) than did their control group counterparts (M=14.78, SD=5.285), indicating greater spatial anxiety [t(84)=−3.886, p<.001]. AD males (M=18.05, SD=5.967) had significantly higher SAS scores than did control males (M=13.93, SD=4.249; t(35)=−2.400, p=0.022). AD females (M=21.24, SD=5.890) had significantly higher SAS scores than did control females (M=15.25, SD=5.798; t(47)=−3.421, p=0.001). Thus, spatial anxiety was higher for both males and females in the AD group compared to the control group.

SAS scores did not differ significantly between males (M=16.05, SD=5.537) and females (M=17.33, SD=6.447) in the overall group [t(84)=−.962, p=.339]. These results did not support our hypothesis that males overall would have less spatial anxiety than females. There also were no significant SAS score differences between control group males (M=13.94, SD=4.249) and females (M=15.25, SD=5.798; t(48)=−0.836, p=.407), or AD group males (M=18.05, SD=5.967) and females (M=21.24, SD=5.890; t(34)=−1.607, p=.117).

Correlations between Wayfinding Strategies, Spatial Anxiety, and Demographic Factors

Table 4 shows correlations between each of the wayfinding strategies, spatial anxiety, and demographic measures. Orientation strategy scores were positively correlated with years of education completed (r=.318, p=.003). Both orientation (r=.280, p=.009) and route strategy scores (r=.295, p=.006) were positively correlated with MoCA score. Route strategy use was also positively correlated with MMSE score (r=.305, p=.004). A moderate negative correlation was found between use of orientation strategy and spatial anxiety score (r=−.434, p=<.001). No significant correlation was found between use of route strategy and spatial anxiety (r=.022, p=.842). Spatial anxiety scores were negatively correlated with years of education (r=−.246, p=.023), MoCA score (r=−.348, p=.001), and MMSE score (r=−.306, p=.004).

Table 4.

Pearson correlations among wayfinding strategies, spatial anxiety, and demographic factors

| Route Total | Spatial Anxiety Scale Total | Age (yrs.) | Education (highest year completed) | MoCA Total | Digital Span: Forward | Digital Span: Backwards | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orientation Total | .039 | −.434*** | .034 | .318** | .280** | −.142 | −.070 |

| Route Total | .022 | −.152 | .041 | .295** | .016 | .097 | |

| Spatial Anxiety Scale Total | −.169 | −.246* | −.348** | .066 | −.194 | ||

| Age (yrs.) | .145 | −.159 | −.044 | −.066 | |||

| Education (highest year completed) | .239* | −.013 | .193 | ||||

| MoCA Total | .119 | .308** | |||||

| Digital Span: Forward | .352** |

Note. MoCA=Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

p<.05.

p<.01.

p<.001.

Discussion

The most important findings from this study were the differences in wayfinding strategies and spatial anxiety scores between older adults with and without AD. These results showed that participants with early-stage AD had significantly lower orientation strategy scores and a trend towards lower route strategy scores. Individuals with AD also had significantly more spatial anxiety than those without AD. These findings are consistent with previous research about wayfinding strategies and AD.

Beginning research has shown older individuals with AD use fewer orientation strategies than do those without AD (Allison et al., 2016). This difference may be related to AD’s early, destructive effects on the hippocampus (Allison et al., 2016; Iaria, Petrides, Pike & Bohot,, 2003). Decreased orientation strategy use also may be related to a reduced ability to maintain attention and recall environmental landmarks, both of which may impair the ability to establish and use a cognitive map (Benke et al., 2014; Chiu et al., 2004; Head & Isom, 2010). Our results showed AD participants were significantly less likely to use orientation strategies than were their control counterparts.

There also is some evidence that individuals with early-stage AD use fewer route strategies compared to older adults without AD (Allison et al., 2016). Although our results did not show a significant difference in route strategy use, there was a trend toward less route strategy use among AD participants. Like orientation strategy use, a reduction in route strategy use also may be related to the reduced ability to maintain attention and recall environmental landmarks (Benke et al., 2014; Chiu et al., 2004; Head & Isom, 2010). Additionally, while the WSS only measured spatial strategies use, persons with AD may resort to other non-spatial strategies (i.e., guessing or trial and error) because they have difficulty using spatial strategies in complex environments.

Our results showed significantly increased spatial anxiety among participants with early-stage AD compared to control group participants. We found no other studies that examined the incidence of spatial anxiety in persons with AD. One contributing factor may be the hippocampal changes that take place in AD, as anxiety has been strongly linked to hippocampal function (Engin & Treit, 2007; Kremmyda et al., 2016). Additionally, previous research has shown spatial anxiety to be associated with decreased orientation strategy use as compared to route strategy use (Lawton, 1994; Lawton & Kallai, 2002). Our findings supported this hypothesis, as a significant negative correlation was found between orientation use and spatial anxiety scores. It is possible that decreased use of orientation strategies results in reduced navigational flexibility, leading to increased spatial anxiety. Additionally, the reduced ability to maintain and use a cognitive map of one’s environment may lead to feelings of disorientation, further escalating anxiety in persons with early-stage AD (Lawton, 1994).

Among participants, we found males were more likely to use orientation strategies than females in both the overall and control groups. This finding is consistent with similar findings from other studies (Davis & Weisbeck, 2015; Lawton, 1994; Lawton & Kallai, 2002). We did not find any difference in spatial anxiety between males and females in either the control or AD study groups. Evidence regarding gender differences in spatial anxiety is mixed (Hund & Minarik, 2006; Lawton, 1994; Lawton & Kallai, 2002). While some have suggested females have more wayfinding-related anxiety than do their male counterparts, our findings did not support this pattern (Lawton, 1994; Lawton & Kallai, 2002).

Among AD participants, the lack of gender differences in spatial anxiety was an interesting finding. The lack of gender differences in spatial anxiety may be related to our sample’s mean age. While previous spatial anxiety studies focused on much younger populations, often college-age individuals, our participants had a mean age of 76 years (Lawton, 1994; Lawton & Kallai, 2002). It is possible that with increasing age, males without cognitive disease retain their advantage over women in orientation strategy use, but have less confidence in their abilities and thus more anxiety. Alternatively, it is possible that males have less orientation strategy use over time—despite still having an advantage over older women—causing them to have spatial anxiety on par with females of that age group.

Several study limitations exist. The relatively small sample size affects the study’s generalizability. In addition, the wayfinding measures relied on self-report in a population with memory impairment. Although our participants were in the very early stages of AD, it is possible that their ability to answer the questions was impaired. Of note, the differences found between the groups with and without AD are congruent with the disease course and known changes that occur in the brain, giving some evidence for these tools’ predictive validity.

This study’s clinical implications are that persons with AD may struggle with wayfinding; and that they have a reduced ability to employ spatial strategies effectively. Large, complex environments, such as senior living communities and hospitals, may prove especially difficult due to a lack of distinctiveness. Because wayfinding impairments have profound implications—such as a loss of independence—interventions to help older persons with AD in wayfinding are needed.

Nurses and other caregivers should be aware that persons with AD may be anxious when asked to find their way, and they may need additional assistance and support. Since persons with AD had more spatial anxiety than those without the disease, regardless of gender, it is important that carers provide support for persons with AD while they are learning new environments. Spatial anxiety has been associated with reduced wayfinding ability in younger persons (Hund & Minarik, 2006); thus, it would be interesting to determine if measures to reduce anxiety (such as reassurance, practice, and support) could improve wayfinding ability in this population. In addition, it is important to analyze the impact of spatial anxiety on persons with AD, such as how it affects independence, spatial/neighborhood mobility, the effect on driving, and the impact on engagement with community resources. Life space, which is the spatial extent of mobility in a person’s environment, has been related to cognitive decline (Crowe, et al., 2008). It makes sense that when persons with AD experience anxiety about wayfinding, they may choose to lessen their engagement with the world. It is possible that part of the reason for a decreased life space in persons with cognitive decline is spatial anxiety.

The study results support that research is needed to test interventions to support persons with AD in wayfinding. Persons with AD may be more dependent upon the legibility of environments as well as personal support to find their way. Studies are needed that examine ways to make complicated environments easier to navigate; such as improved signage, the use of cues, and technological devices to assist with wayfinding. For example, several studies have shown that large, bright, easily distinctive cues can help persons with AD find their way in complex environments (Cogne et al., 2018; Davis, Ohman & Weisbeck, 2017), and that special signage using icons, words, and high contrast letters and background, can assist with wayfinding (Brush, Camp, Bohach & Gerstberg, 2015).

The finding that participants with AD had lower orientation strategy scores than the demographically similar control group beg the question of whether or not a change in wayfinding strategy use may be an early disease indicator. Although we included only people with diagnosed AD or MCI due to AD, it would be beneficial to assess whether these changes occur prior to diagnosis. Scientists have shown that a decline in orientation strategies can be linked to hippocampal changes indicative of developing AD (Konishi et al., 2018). Thus, a decline in spatial strategy use may be an early biomarker for AD development, which could lead to early diagnosis.

This study adds to the literature regarding wayfinding strategy use and anxiety in individuals with and without AD. Our findings also add to existing evidence that changes in wayfinding strategy use may be an early clinical indicator for AD (Bianchini et al., 2014). These results may help guide development of wayfinding interventions for individuals with AD.

Acknowledgments

Author Note: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15AG037946. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Rebecca Davis, Kirkhof College of Nursing, Grand Valley State University.

Amy Veltkamp, Registered Nurse, Spectrum Health, Grand Rapids, MI.

References

- Allison SL, Fagan AM, Morris JC, & Head D (2016). Spatial navigation in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 52(1), 77–90. 10.3233/JAD-150855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2019). 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Retrieved from https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures

- Benke T, Karner E, Petermichl S, Prantner V, & Kemmler G (2014). Neuropsychological deficits associated with route learning in Alzheimer disease, MCI, and normal aging. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 28(2), 162–167. 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini F, Di Vita A, Palermo L, Piccardi L, Blundo C, & Guariglia C (2014). A selective egocentric topographical working memory deficit in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease: A preliminary study. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 29(8), 749–754. 10.1177/1533317514536597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BrightFocus Foundation (2019). Alzheimer’s disease: Facts and figure. Retrieved from https://www.brightfocus.org/alzheimers/article/alzheimers-disease-facts-figures

- Boone AP, Gong X, & Hegarty M (2018). Sex differences in navigation strategy and efficiency. Memory & Cognition, 46(6), 909–922. 10.3758/s13421-018-0811-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brush JA, Camp C, Bohach S, & Gerstberg N (2015). Developing a signage system that supports wayfinding and independence for persons with dementia. Canadian Nursing Home, 26(1), 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi E (2014). Wayfinding difficulties among elders with dementia in an assisted living residence. Dementia, 13(4), 429–450. 10.1177/1471301214535134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu Y, Algase D, Whall A, Liang J, Liu H, Lin K, & Wang P (2004). Getting lost: Directed attention and executive functions in early Alzheimer’s disease patients. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 17(3), 174–180. 10.1159/000076353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogne M, Auriacombe S, Vasa L, Tison F, Klinger E, Sauzeon H, & Pierre-Alaine J (2018). Are visual cues helpful for virtual spatial navigation and spatial memory in patients with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease? Neuropsychology, 32(4), 385–400. doi: 10.1037/neu0000435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo D, Serino S, Tuena C, Pedroli E, Dakanalis A, Cipresso P, & Riva G (2017). Egocentric and allocentric spatial reference frames in aging: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 80, 605–621. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe M, Andel R, Wadley VG, Okonkwo OC, Sawyer P, & Allman RM (2008). Life-space and cognitive decline in a community-based sample of African American and Caucasian older adults. Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 63(11), 1241–1245. 10.1093/gerona/63.11.1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R, Ohman JM, & Weisbeck C (2017). Salient cues and wayfinding in Alzheimer’s disease within a virtual senior residence. Environment and Behavior, 49(9), 1038–1065. 10.1177/0013916516677341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RL, & Therrien BA (2012). Cue color and familiarity in place learning for older adults. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 5(2), 138–148. 10.3928/19404921-20111004-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RL, & Weisbeck C (2015). Search strategies used by older adults in a virtual reality place learning task. The Gerontologist, 55(Suppl 1), S118–S127. 10.1093/geront/gnv020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engin E, & Treit D (2007). The role of hippocampus in anxiety: Intracerebral infusion studies. Behavioural Pharmacology, 18(5–6), 365–374. 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282de7929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, & McHugh PR (1975). “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazova I, Laczó J, Rubinova E, Mokrisova I, Hyncicova E, Andel R, … Hort J (2013). Spatial navigation in young versus older adults. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 5, 94 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MA, & Wolbers T (2014). How age-related strategy switching deficits affect wayfinding in complex environments. Neurobiology of Aging, 35(5), 1095–1102. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.10.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head D, & Isom M (2010). Age effects on wayfinding and route learning skills. Behavioural Brain Research, 209(1), 49–58. 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C Berg L, Danziger W, Coben L & Martin R (1982). A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 140(6), 566–572. 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hund A, & Minarik J (2006). Getting from here to there: Spatial anxiety, wayfinding strategies, direction type, and wayfinding efficiency. Spatial Cognition and Computation, 6(3), 179–201. 10.1207/s15427633scc0603_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iaria G, Palermo L, Committeri G, & Barton J (2009). Age differences in the formation and use of cognitive maps. Behavioural Brain Research, 196(2), 187–191. 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.08.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iaria G, Petrides M, Dagher A, Pike B, & Bohbot V (2003). Cognitive strategies dependent on the hippocampus and caudate nucleus in human navigation: Variability and change with practice. The Journal of Neuroscience, 23(13), 5945–5952. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05945.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi K, Joober R, Poirier J, MacDonald K, Chakravarty M, Patel R, … Bohbot VD (2018). Healthy versus entorhinal cortical atrophy identification in asymptomatic APOE4 carriers at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 61(4), 1493–1507. 10.3233/JAD-170540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremmyda O, Hüfner K, Flanagin V, Hamilton DA, Linn J, Strupp M, … Brandt T (2016). Beyond dizziness: Virtual navigation, spatial anxiety and hippocampal volume in bilateral vestibulopathy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 139 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton C (1994). Gender differences in way-finding strategies: Relationship to spatial ability and spatial anxiety. Sex Roles, 30(11–12), 765–779. 10.1007/BF01544230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton C , & Kallai J (2002). Gender differences in wayfinding strategies and anxiety about wayfinding: A cross-cultural comparison. Sex Roles, 47(9–10), 389–401. 10.1023/A:1021668724970 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak M (1995). Neuropsychological assessment (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moffat S, Elkins W, & Resnick S. (2006). Age differences in the neural systems supporting human allocentric spatial navigation. Neurobiology of Aging, 27(7), 965–972. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L & Muthén B. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen. [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine Z, Phillips N, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, … Chertkow H (2005). The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(4), 695–699. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai M, & Jacobs W (2004). Topographical disorientation in community-residing patients with Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(3), 250–255. 10.1002/gps.1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passini R, Pigot H, Rainville C, & Tétreault MH (2000). Wayfinding in a nursing home for advanced dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Environment and Behavior, 32(5), 684–710. 10.1177/00139160021972748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotin A, Desgranges B, Landeau B, Mézenge F, La Joie R, Egret S, … Chételat G (2015). Anosognosia in Alzheimer disease: Disconnection between memory and self-related brain networks. Annals of Neurology, 78(3), 477–486. 10.1002/ana.24462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piras F, Piras F, Orfei MD, Caltagirone C, & Spalletta G (2016). Self-awareness in Mild Cognitive Impairment: Quantitative evidence from systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 61, 90–107. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B, Gruber-Baldini AL, Pretzer-Aboff I, Galik E, Buie VC, Russ K, & Zimmerman S (2007). Reliability and validity of the evaluation to sign consent measure. The Gerontologist, 47(1), 69–77. 10.1093/geront/47.1.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers M, Sindone III J, & Moffat S (2012). Effects of age on navigation strategy. Neurobiology of Aging, 33, 202.e215–202. e222. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe M, & Bennett V (2003). A look at deaths occurring in persons with dementia lost in the community. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 18(6), 343–348. 10.1177/153331750301800612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seignourel P, Kunik M, Snow L, Wilson N, & Stanley M (2008). Anxiety in dementia: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(7), 1071–1082. 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Gildeh N, & Holmes C (2007). The Montreal Cognitive Assessment: Validity and utility in a memory clinic setting. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 52(5), 329–332. 10.1177/070674370705200508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taillade M, Sauzéon H, Dejos M, Pala P, Larrue F, Wallet G, … N’Kaoua B (2013). Executive and memory correlates of age-related differences in wayfinding performances using a virtual reality application. Neuropsychology, Development, and Cognition. Section B, Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition, 20(3), 298–319. 10.1080/13825585.2012.706247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Alpass F, Stephens C, & Towers A (2010). Driving anxiety and fear in young older adults in New Zealand. Age and Ageing, 40(1), 62–66. 10.1093/ageing/afq154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weschler D (1987). Weschler Memory Scale—revised manual. New York, NY: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]