Abstract

A variety of new psychoactive substances (NPS) are appearing in recreational drug markets worldwide. NPS are compounds that target various receptors and transporters in the central nervous system to achieve their psychoactive effects. Chemical modifications of existing drugs can generate NPS that are not controlled by current legislation, thereby providing legal alternatives to controlled substances such as cocaine or amphetamine. Recently, 3-fluorophenmetrazine (3-FPM), a derivative of the anorectic compound phenmetrazine, appeared on the recreational drug market and adverse clinical effects have been reported. Phenmetrazine is known to elevate extracellular monoamine concentrations by an amphetamine-like mechanism. Here we tested 3-FPM and its positional isomers, 2-FPM and 4-FPM, for their abilities to interact with plasma membrane monoamine transporters for dopamine (DAT), norepinephrine (NET) and serotonin (SERT). We found that 2-, 3- and 4-FPM inhibit uptake mediated by DAT and NET in HEK293 cells with potencies comparable to cocaine (IC50 values < 2.5 µM), but display less potent effects at SERT (IC50 values >80 µM). Experiments directed at identifying transporter-mediated reverse transport revealed that FPM isomers induce efflux via DAT, NET and SERT in HEK293 cells, and this effect is augmented by the Na+/H+ ionophore monensin. Each FPM evoked concentration-dependent release of monoamines from rat brain synaptosomes. Hence, this study reports for the first time the mode of action for 2-, 3- and 4-FPM and identifies these NPS as monoamine releasers with marked potency at catecholamine transporters implicated in abuse and addiction.

Keywords: New psychoactive substances, legal high, phenmetrazine, monoamine transporter, amphetamine

1. Introduction

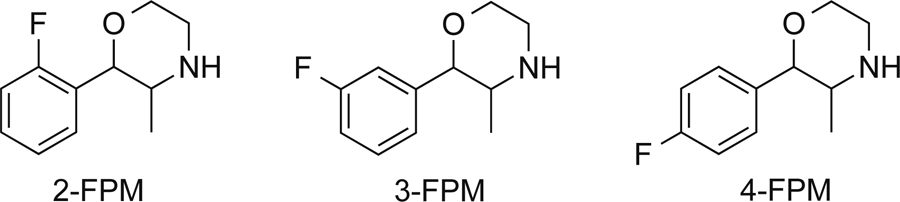

Novel synthetic drugs of abuse, more formally known as new psychoactive substances (NPS), are appearing at a rapid pace on recreational drug markets worldwide (Welter-Luedeke and Maurer, 2016). NPS are designed to imitate the actions of known drugs of abuse (e.g. amphetamines), while circumventing current legal restrictions on controlled substances due to their unique chemical structures (Baumann et al., 2014). NPS are marketed and sold over the Internet under various names like “research chemicals”, “bath salts” or ”legal highs”, and there is legitimate concern about their negative impacts on public health (Tettey and Crean, 2015). Based on the surveillance model first developed by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) launched the Early Warning Advisory (EWA) in 2013 to monitor the appearance of NPS on a global scale. Recently, the EWA identified 3-fluorophenmetrazine (3-FPM) as an NPS on Internet websites, and information from drug user forums suggests the drug exhibits psychostimulant properties in human users (See Figure 1 for the chemical structures of 3-FPM and its positional isomers). Notably, the parent compound phenmetrazine was once prescribed as an anorectic medication but was withdrawn from the clinical market because of its abuse potential (Griffiths et al., 1976, Banks et al., 2013).

Figure 1:

Chemical structures of fluorophenmetrazine isomers, 2-, 3- and 4-FPM

The process of developing and manufacturing NPS hinges on easy access to the biomedical literature where multiple information sources, such as patent applications and medicinal chemistry journals, provide a rich source of ideas for clandestine chemists (Brandt et al., 2014). The preparation of 3-FPM was first published in 2011 as part of a patent application for morpholine-based compounds that were being investigated for a range of potential therapeutic applications (Blough, 2011, Blough, 2013). Similar to other psychostimulant drugs, phenmetrazine interacts with plasma membrane monoamine transporters (MATs) expressed on the surface of various cell types (Rothman et al., 2002). MATs, or neurotransmitter:sodium symporters, belong to the solute carrier 6 family of proteins (SLC6) and mediate the uptake of monoamine neurotransmitters from the extracellular space (Kristensen et al., 2011). Specific transporters for serotonin (SERT, SLC6A4), dopamine (DAT, SLC6A3) and norepinephrine (NET, SLC6A2) exploit the sodium gradient across cell membranes to drive the movement of monoamines from the synaptic cleft into the neuronal cytoplasm, thus tightly regulating the strength and the duration of monoamine signaling (Torres et al., 2003). MATs represent major targets for clinically relevant drugs (e.g., antidepressants) but also for a plethora of abused substances, like cocaine and amphetamine (Kristensen et al., 2011).

All psychostimulants that target MATs increase extracellular concentrations of monoamines in the central and peripheral nervous systems. However, the precise mode of drug action may be subdivided into cocaine-like “blockers” and amphetamine-like “releasers” (Sitte and Freissmuth, 2010). MAT blockers bind to the orthosteric site on transporters and act as non-transported uptake inhibitors (Plenge et al., 2012). Cocaine is the prototypical MAT blocker. However, additional mechanisms for cocaine action have been reported, including monoamine release via reverse transport and enhanced exocytosis (Venton et al., 2006, Heal et al., 2014). MAT releasers also bind to transporters, but these drugs are subsequently transported into the cytoplasm where they reverse the normal direction of transporter flux to trigger efflux of neurotransmitters (Robertson et al., 2009). Substrate-type releasers are transported across cellular membranes along with sodium ions and at sufficiently high intracellular concentrations, these drugs can redistribute neurotransmitters from vesicular storage pools into the cytosol (Sulzer et al., 2005, Sitte and Freissmuth, 2010). As a consequence, the intracellular concentrations of free monoamine neurotransmitters and sodium cations build up at the inner side of the plasma membrane to enable transporter-mediated reverse transport (Sitte and Freissmuth, 2015).

Previous research shows that phenmetrazine acts as a substrate-type releaser at DAT and NET, with much weaker effects at SERT (Rothman et al., 2002). Chemical modification of amphetamine-type stimulant drugs can produce profound changes in their profile of pharmacological effects. For instance, addition of a fluorine to the 4-position on the phenyl ring of amphetamine increases potency towards SERT relative to DAT (Marona-Lewicka et al., 1995, Nagai et al., 2007, Baumann et al., 2011, Rickli et al., 2015). Limited information is available on the pharmacology of 3-FPM (Blough, 2011, Blough, 2013), so we sought to characterize the molecular mode of action of this drug in cells expressing human transporters and in native tissue preparations from rat brain. Based on the available structure-activity data for amphetamine-type compounds (Cozzi et al., 2013), we hypothesized that addition of a fluoro substitution to the phenyl ring of phenmetrazine would enhance the potency of analogs toward SERT compared to DAT. In vitro uptake inhibition and efflux assays were used to elucidate the mechanism of action of 3-FPM at MATs, and to evaluate whether the drug induces transporter-mediated release consistent with an amphetamine-type action. Two positional isomers, 2-FPM and 4-FPM, were included in our study for comparison, because isomers of NPS often appear in the marketplace and present challenges from a clinical and forensic perspective (Brandt et al., 2015, Brandt et al., 2014, Elliott et al., 2013, Dinger et al., 2016, Marusich et al., 2016, McLaughlin et al., 2016).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Chemicals

2-(2-Fluorophenyl)-3-methylmorpholine (2-FPM), 2-(3-fluorophenyl)-3-methylmorpholine (3-FPM) and 2-(4-fluorophenyl)-3-methylmorpholine (4-FPM) were prepared as fumarate salts and analytically characterized previously (McLaughlin et al., 2016). [3H]5HT (28.3 µCi mmol−1) was purchased from PerkinElmer (Boston, MD, USA), and [3H]MPP+ (80–85 µCi mmol−1) was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA). Cell culture dishes were from Sarstedt AG&Co., Nuembrecht, Germany. All other chemicals and reagents, including cell culture supplies, were purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

2.2. Cell Culture

Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Essential Medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, streptomycin (100 µg 100 mL−1) and penicillin (100 IU 100 mL−1), and kept in humidified atmosphere (5 % CO2, 37 °C). The generation of HEK293 cells stably expressing human DAT (hDAT) and human NET (hNET) is described elsewhere (Scholze et al., 2002). Human SERT (hSERT) was cloned in frame with monomeric GFP (mGFP) into a tetracycline inducible expression vector pcDNA 4/TO (Invitrogen by life-Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The generation of stable cell lines was performed as described previously (Hilber et al., 2005).

The selection of HEK293 cells stably expressing hDAT or hNET was executed by constantly adding geneticin (50 µg mL−1). For hSERT expressing HEK293 cells the selection pressure was maintained by adding blasticidin (10 µg mL−1) and zeocin (300 µg mL−1) to the cell culture medium. Expression of hSERT was induced with tetracycline (1 µg mL−1) 24 h prior to the experiment.

2.3. Radiotracer Uptake and Efflux Experiments in HEK293 Cells

Uptake inhibition and efflux experiments were performed as described elsewhere (Mayer et al., 2017). Briefly, for uptake experiments, HEK293 cells expressing the desired transporter were seeded at a density of 4 ×104 cells per well on a poly-d-lysine (PDL) coated 96-well plate the day before the experiment. The cells were incubated for 5 min with various concentrations of 2-, 3- or 4-FPM in Krebs-HEPES buffer (KHB) (25 mM Hepes, 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4 and 5 mM D-glucose, pH 7.3) to allow for equilibration before the addition of radiolabeled substrate. The radiolabeled substrate for hDAT and hNET was [3H]MPP+ (20 nM) whereas the radiolabeled substrate for hSERT was [3H]5HT (100 nM). After incubation for 180 s (hDAT and hNET) or 60 s (hSERT), radioactive substrate was aspirated and the cells were washed with ice cold KHB to terminate uptake. Subsequently, the cells were lysed in sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS, 1 %; 200 µL per well) and the amount of radioactivity within each well was assessed by use of a liquid scintillation counter. Nonspecific uptake was determined in the presence of 10 µM mazindol for hDAT and hNET or 10 µM paroxetine for hSERT. For analysis, nonspecific uptake was subtracted from all values and uptake was expressed as percent of control uptake, i.e. uptake in absence of inhibitor, and plotted against increasing concentrations of inhibitor.

For efflux experiments, 4 ×104 HEK293 cells expressing hDAT, hNET or hSERT were seeded onto PDL-coated 5mm glass-coverslips. The cells were pre-loaded with 0.1 µM [3H]MPP+ (hDAT and hNET) or 0.4 µM [3H]5HT (hSERT) in KHB for 20 min at 37°C. Subsequently, the cells were transferred into small chambers with a volume of 200 µL and superfused with KHB (25°C, 0.7 mL per minute) for 40 min to establish a stable baseline. At t= −12, the experiment was started by collecting three 2-min fractions of superfusate to record the basal efflux, followed by the addition of monensin (10 µM) (at t= −8) or solvent for four fractions. Finally, the cells were exposed to 2-, 3- or 4-FPM (5 µM) (at t=0) for five fractions and then lysed in 1% SDS. Radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting and radioactivity per fraction was expressed as fractional release, i.e. the percentage of released [3H] versus the amount of [3H] present at the beginning of that fraction (Sitte et al., 2000).

2.4. Whole-cell Patch Clamp

Whole-cell Patch Clamp: HEK293 cells stably expressing hSERT were seeded at low density 24 h before recordings. Currents through the transporter were measured in the whole-cell patch clamp configuration. The electrode resistance was between 2–5 megohms. For the recordings, we used the following internal solution: 133 mM potassium gluconate, 6 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.7 mM MgCl2, 10 mM EGTA, and 10 mM HEPES adjusted to pH 7.2 with KOH. The external solution in all experiments was 140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 20 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. For rapid solution exchange, we used an OctaFlow superfusion device (ALA Scientific, Farmingdale, NY). Cells were clamped to −60mV and continuously superfused either with blank external solution or an external solution containing the tested compounds. For current acquisition, we employed an Axopatch 200B amplifier and pClamp 10.2 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The washout period following substrate/inhibitor application was 60 s in all cases. Current traces were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz using a Digidata 1550 (Molecular Devices). The currents were quantified using Clampfit 10.2 software. Passive holding currents were subtracted, and the traces were filtered using a 100-Hz digital Gaussian low-pass filter.

2.5. Radiotracer flux experiments in rat brain synaptosomes

All experiments utilizing animal tissue were performed in agreement with the ARRIVE guidelines. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Frederick, MD, US) weighing 250–350 g were maintained in facilities fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and experiments were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Intramural Research Program (IRP). Rats were double-housed and maintained on a 12 h light:dark cycle (lights on from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM), with food and water available ad libitum. On the day of an experiment, rats were euthanized by CO2 narcosis and brains were processed to yield synaptosomes as previously described (Rothman et al., 2002). Brain tissue was obtained between 10:00 AM and noon for all experiments. Synaptosomes were prepared from rat striatum for the DAT assays, whereas synaptosomes were prepared from whole brain minus striatum and cerebellum for the NET and SERT assays. For the release assays, 9 nM [3H]MPP+ was used to assess activity at DAT and NET while 5 nM [3H]5-HT was used to assess activity at SERT. All buffers used in the release assays contained 1 µM reserpine to block vesicular uptake of substrates. The selectivity of release assays was optimized for a single MAT by including unlabeled blockers to prevent uptake of substrates by competing transporters. Specifically, for NET assays, 100 nM GBR12935 and citalopram were added; for SERT assays, 100 nM GBR12935 and nomifensine were added; for DAT assays, 100 nM desipramine and citalopram were added. Synaptosomes were preloaded with radiolabeled substrate in Krebs-phosphate buffer (126 mM NaCl, 2.4 mM KCl, 0.5 mM KH2PO4, 1.1 mM CaCl2, 0.83 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM Na2SO4, 11.1 mM glucose, 13.7 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mg per mL ascorbic acid, and 0.05 mM pargyline, pH 7.4) and incubated for 1 h to achieve steady state. Release assays were initiated by adding 850 µL of preloaded synaptosomes to 150 µL of test compound prepared in Krebs-phosphate buffer containing 1 mg mL−1 BSA. Maximal release was determined in the presence of tyramine (10 µM for DAT/NET and 100 µM for SERT). Assays were terminated (30 min for DAT and NET, 5 min for SERT) by rapid vacuum filtration/washing through GF/B filters on a Brandel harvester (Gaithersburg, MD, USA), and retained radioactivity was quantified by a PerkinElmer TopCount. Percent of maximal release was plotted against the log of compound concentration. Data were fit to a three-parameter logistic equation to generate EC50 values (GraphPad Prism 6.0, GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

2.6. Analysis and statistics

All experimental data are represented as mean ± SEM. For statistical comparisons, release of preloaded tritiated substrate in the presence or absence of monensin was analyzed by two-way ANOVA (treatment x time) followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test. P <0.05 was chosen as the minimum criterion for statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Fluorinated phenmetrazines inhibit transporter-mediated uptake

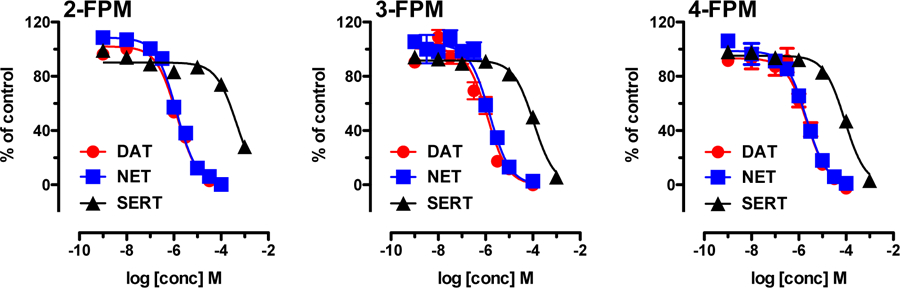

2-, 3- and 4-FPM were tested for their ability to inhibit uptake mediated by hDAT, hNET or hSERT in HEK293 cells. As depicted in Figure 2, each compound elicited concentration-dependent inhibition of MAT-mediated uptake, and the relevant IC50 values are summarized in Table 1. For hDAT and hNET, IC50 values were in the low micromolar range, not exceeding 2.5 µM (Table 1). For hSERT, potencies to inhibit uptake were much weaker, with IC50 values ranging from 88 to 454 µM. The IC50 values for 3-FPM and 4-FPM at hSERT were 111.65 (± 13.08) and 88.09 (±1.83) µM, whereas the IC50 for 2-FPM was 454 (±15.4) µM. Notably, movement of the fluoro substitution from the 2-, to 3-, to 4-position produced a progressive stepwise increase in relative potency at hSERT as compared to hDAT and hNET. This observation is best illustrated by a progressive decrease in DAT/SERT ratio and NET/SERT ratio (Table 1). By contrast, the DAT/NET ratio was not affected by the position of the fluoro substitution, with ratios close to unity for all drugs (Table 1). Overall, the IC50 values point toward high selectivity for catecholaminergic transporters, i.e. DAT and NET, versus SERT.

Figure 2:

Effects of fluorinated phenmetrazines on transporter-mediated uptake in HEK293 cells expressing human MATs. Cells were incubated with 0.02 µM [3H]MPP+ for hDAT and hNET assays or 0.1 µM [3H]5HT for hSERT assays, along with various concentrations of fluorinated phenmetrazines. Non-specific uptake was determined in the presence of 10 µM mazindol for DAT and NET or 10 µM paroxetine for SERT. All data are presented as mean ± SEM from 3 experiments performed in triplicate.

Table 1:

IC50 values for inhibition of transporter-mediated uptake by FPM isomers in HEK293 cells. Values are given as mean ± SEM obtained from nonlinear curve fits obtained from n=3 independent experiments, performed in triplicate (data shown in Figure 2). DAT/SERT ratio is expressed as 1/(DAT IC50) divided by 1/(SERT IC50); higher values indicate greater selectivity for DAT. NET/SERT ratio is expressed as 1/(NET IC50) divided by 1/(SERT IC50); higher values indicate greater selectivity for NET. DAT/NET ratio is expressed as 1/(DAT IC50) divided by 1/(NET IC50); higher numbers indicate greater DAT-selectivity.

| IC50 (µM) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAT | NET | SERT | DAT / SERT ratio | NET / SERT ratio | DAT / NET ratio | |

| 2-FPM | 1.33 ± 0.09 | 1.29 ± 0.03 | 454 ± 15.4 | 340.1 | 351.4 | 0.97 |

| 3-FPM | 1.16 ± 0.29 | 1.51 ± 0.17 | 111.65 ± 13.08 | 96.4 | 73.7 | 1.31 |

| 4-FPM | 2.14 ± 0.39 | 2.05 ± 0.28 | 88.09 ± 1.83 | 41.2 | 42.9 | 0.96 |

3.2. Fluorinated phenmetrazines induce transporter-mediated reverse transport

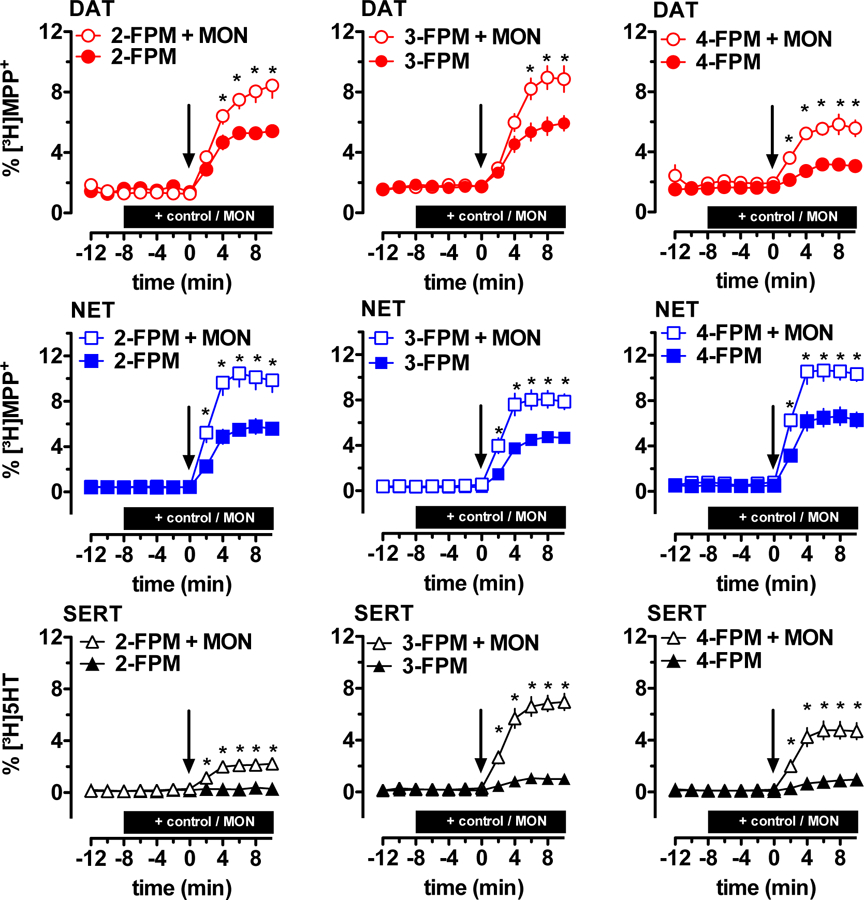

Although uptake inhibition assays can identify drugs which interact with MATs, the uptake assays cannot distinguish between drugs acting as blockers versus those acting as substrate-type releasers. Consequently, we examined the effects of fluorinated phenmetrazines in an efflux assay which can identify transporter releasers. Figure 3 shows the effects of 2-, 3- and 4-FPM on MAT-mediated reverse transport in HEK293. Cells expressing the desired transporter were preloaded with [3H]MPP+ for hDAT and hNET, or [3H]5-HT for hSERT, and subsequently superfused. At hDAT and hNET, the addition of 2-, 3- or 4-FPM (5 µM each, min 2 to 10) increased tritium outflow above basal levels (Figure 3, closed symbols and supplementary Figure 1). At SERT, 3- and 4-FPM significantly enhanced basal release of [3H]5-HT, but 2-FPM did not (Figure 3, closed symbols and supplementary Figure 1). A key aspect of our efflux experiments was the pretreatment of cells with either control buffer or buffer containing the Na+/H+-ionophore monensin. It is well established that monensin (10 µM) disrupts the sodium gradient across cell membranes (Mollenhauer et al., 1990), thereby selectively enhancing substrate-induced reverse transport via MATs (Scholze et al., 2000). As depicted in Figure 3, the efflux of [3H]substrate induced by all three fluorinated phenmetrazines at hDAT, hNET and hSERT was markedly enhanced by monensin (Figure 3, open symbols). A two-way ANOVA (treatment x time) was carried out to examine the effects of each FPM at each transporter, where the two treatment groups were: 1) monensin plus drug or 2) buffer plus drug. Bonferroni post-hoc tests were used to determine significant differences between drug with monensin as compared to drug without monensin at each time point. The data reveal that monensin treatment significantly augmented FPM-induced [3H]substrate release. For 2-FPM, there was a main effect of treatment at hDAT F1,20=5.49, P < 0.05; hNET F1,31=14.31, P < 0.001; and hSERT F1,34=19.78, P < 0.0001. For 3-FPM there was a main effect of treatment at hDAT F1,21= 6.82, P < 0.05; hNET F1,30=12.37, P < 0.01; and hSERT F1,26=66.44, P < 0.0001. And for 4-FPM there was an analogous effect of treatment at hDAT F1,22=8,51, P < 0.01; hNET F1,28=13,42, P < 0.001; and hSERT F1,39=25,04, P < 0.0001.

Figure 3:

Effects of fluorinated phenmetrazines on transporter-mediated efflux of tritiated substrates in HEK293 cells expressing human MATs. Cells were preloaded with [3H]MPP+ for hDAT and hNET assays, or [3H]5HT for hSERT assays, and subsequently perfused. After three basal fractions monensin or control buffer was added at t = −8 min (MON, 10 µM, indicated by black bar). Subsequently, the cells were exposed to FPMs at t = 0 min (5 µM, addition at t = 0 min indicated by arrow). All data are represented as mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test. * denotes p <0.05 when compared to the corresponding control buffer condition.

3.3. 2-,3- and 4-FPM induce transporter-mediated currents

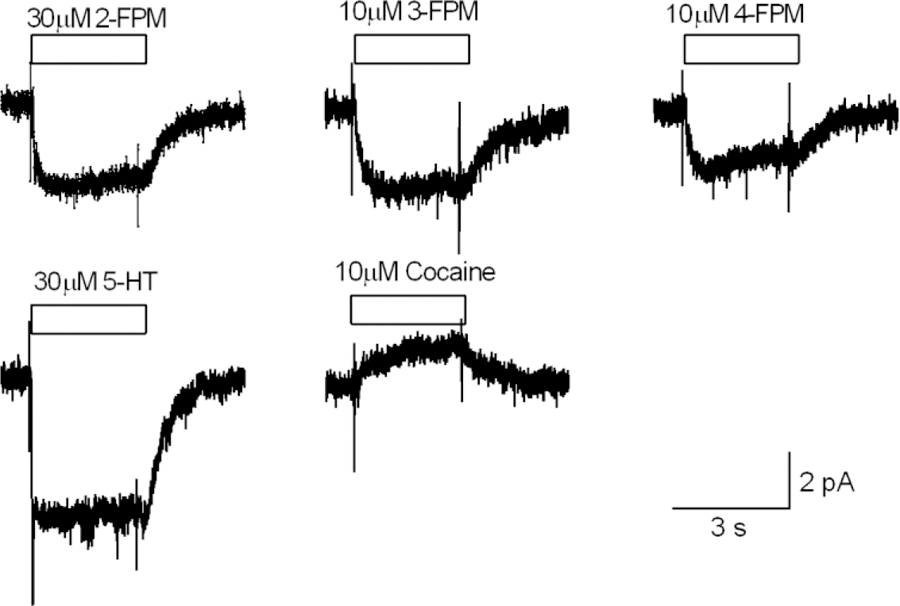

In DAT and NET expressing cells, 2-, 3- and 4-FPM robustly elevated the basal efflux of preloaded tritiated substrate and this effect could be further augmented by co-application of monensin (Figure 3). At SERT, however, application of the individual FPMs resulted in less marked effects. To rule out the possibility that the FPM-induced increases in basal tritium efflux at SERT stem from unmasked basal [3H]substrate-leakage in presence of an inhibitor, we performed electrophysiological recordings. In SERT-expressing cells, application of substrates results in inwardly directed currents (Mager et al., 1994). On the contrary, this does not apply to inhibitors (Sandtner et al., 2016). As depicted in Figure 4, application of 2-, 3- or 4-FPM, as well as the endogenous SERT-substrate 5-HT, evoked inwardly directed ionic currents. This was in obvious contrast to the effects observed in presence of the SERT-inhibitor cocaine which induced no current.

Figure 4:

Representative traces of ionic currents mediated via hSERT, recorded from the same cell (3 different batches of cells were recorded). The three upper panels show currents induced by 30 µM 2-FPM (−4 pA; n = 7), 10 µM 3-FPM (−3.8 pA; n = 6) and 10 µM 4-FPM (−2.5 pA; n = 7), respectively. These currents were inwardly directed and resembled the current induced by 30 µM 5-HT (−7 pA; n = 3) (left lower panel). Application of cocaine (10 µM; n = 4) gave rise to an outwardly directed current, which presumably reflected blockage of a substrate independent leak conductance through hSERT.

3.4. Effects of 2-,3- and 4-FPM on transporters in synaptosomes

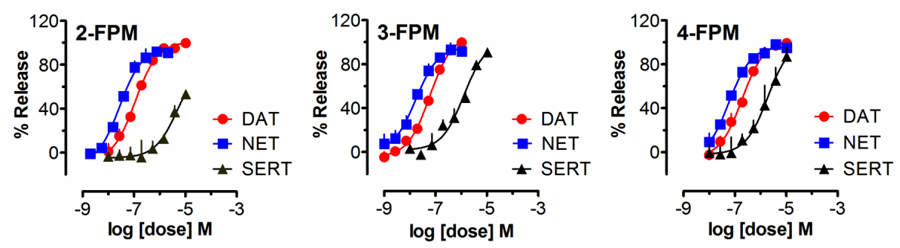

Heterologous expression of MATs in non-neuronal cells provides a convenient experimental system, but such conditions are artificial when compared to MATs expressed in situ. Hence, we performed release assays in rat brain synaptosomes (Baumann et al., 2012), an experimental system where transporters are expressed in their natural microenvironment including the components involved in neurotransmission (Gray and Whittaker, 1962, Wilhelm et al., 2014). As a means to avoid confounding factors associated with the vesicular accumulation of [3H]substrate, the release experiments were performed in presence of 1 µM reserpine. The data in Figure 5 demonstrate that fluorinated phenmetrazines act as fully efficacious releasers at MATs naturally expressed in rat brain synaptosomes. The findings show that the tested phenmetrazine analogues act as MAT-substrates rather than blockers, since “pseudo-efflux” of tritiated substrates caused by uptake blockade rarely exceeds 25–30% of maximal efficacy in this assay (Baumann et al., 2013). In line with data obtained from HEK293 cells (Figure 2), the fluorinated phenmetrazines affected DAT and NET with comparable potencies. Further, as observed in HEK293 cells, a progressive decrease in the relative selectivity for DAT versus SERT could be detected as the fluoro substitution was moved from the 2-, to 3-, to 4-position. The EC50 values and the relative ratios obtained from non-linear curve fits in Figure 5 are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 5:

Effects of fluorinated phenmetrazines on transporter-mediated release of tritiated substrates from rat brain synaptosomes. Rat brain synaptosomes were preloaded with [3H]MPP+ for DAT and NET assays, or [3H]5HT for SERT assays, and subsequently exposed to various concentrations of 2-, 3- or 4-FPM. Release assays were optimized for DAT, NET or SERT using unlabeled inhibitors as outlined in the materials and methods section. Data are mean ± SEM obtained from 3 experiments performed in triplicate.

Table 2:

EC50 values for transporter-mediated release by FPM isomers in rat brain synaptosomes. Values are given as mean ± SEM obtained from nonlinear curve fits as shown in Figure 4. DAT/SERT ratio is expressed as 1/(DAT EC50) divided by 1/(SERT EC50); higher values indicate greater selectivity for DAT. NET/SERT ratio is expressed as 1/(NET EC50) divided by 1/(SERT EC50); higher values indicate greater selectivity for NET. DAT/NET ratio is expressed as 1/(DAT EC50) divided by 1/(NET EC50); higher numbers indicate greater DAT-selectivity.

| EC50 (nM) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAT | NET | SERT | DAT / SERT ratio | NET / SERT ratio | DAT / NET ratio | |

| 2-FPM | 112 ± 10 | 28 ± 3 | 4808 ± 1265 | 43 | 172 | 0.25 |

| 3-FPM | 60 ± 4 | 17 ± 4 | 1269 ± 207 | 21 | 75 | 0.28 |

| 4-FPM | 191 ± 17 | 58 ± 7 | 1895 ± 424 | 10 | 33 | 0.30 |

4. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to determine the molecular mechanism of action for the fluoro ring-substituted analogues 2-, 3-, and 4-FPM. Previous evidence shows the parent compound phenmetrazine is a substrate-type releaser at DAT and NET in rat brain tissue, with much weaker substrate activity at SERT (Rothman et al., 2002). Solis and colleagues recently reported that phenmetrazine induces an inwardly-directed sodium current in cells expressing hDAT, consistent with its activity as a transportable DAT substrate (Solis et al., 2016). We speculated that addition of a fluorine substituent to the phenyl ring of phenmetrazine (Figure 1) might alter the relative potency of the isomers at SERT relative to DAT and NET. Data obtained here from uptake inhibition experiments in HEK293 cells show that the effects of FPM isomers are generally comparable to the parent compound phenmetrazine, with compounds exhibiting a pronounced selectivity for hDAT and hNET over hSERT. As depicted in Figure 2, each phenmetrazine isomer inhibited MAT-mediated uptake in a concentration-dependent manner. At hDAT and hNET, the test drugs potently inhibited the uptake of [3H]MPP+ with IC50 values in the low micromolar range. Uptake inhibition at hSERT was markedly less potent with corresponding IC50 values in the range of 88–445 µM (Figure 2 and Table 1). Notably, movement of the fluoro substitution from the 2-, to 3-, to 4-position produced a progressive stepwise increase in relative potency at SERT when compared to the catecholamine transporters.

As mentioned in the Introduction, psychostimulants can be subdivided into cocaine-like blockers and amphetamine-like releasers. Uptake inhibition assays can be used to identify drugs that interact with MATs, but these assays cannot distinguish non-transported uptake inhibitors from transported substrates (Baumann et al., 2012). Hence, superfusion studies were performed in HEK cells expressing MATs to delineate the possible impact of 2-, 3- and 4-FPM on transporter-mediated reverse transport. These experiments allow for monitoring the time-dependent release of preloaded [3H]MPP+ via hDAT and hNET or [3H]5HT via hSERT in the absence or presence of test drugs. At hDAT and hNET, the fluorinated phenmetrazines had similar effects, as each FPM elevated the release of tritiated substrate when compared to untreated basal efflux (Figure 3). At hSERT, more divergent effects on release were detected with the isomers. The addition of 3- or 4-FPM induced moderate release of [3H]5HT whereas 2-FPM had no detectable effect on SERT mediated efflux at the concentration tested (Figure 3). The latter finding is consistent with the uptake inhibition experiments in which 3- and 4-FPM exerted weak but measurable inhibitory effects on SERT mediated uptake, whereas no obvious effect could be observed for 2-FPM at concentrations below 30 µM (Figure 2). The notion that the FPMs reverse the normal direction of transporter flux to induce release is bolstered by the fact that monensin augmented the effects on tritium overflow. Since MATs strictly depend on the sodium gradient as a driving force (Kristensen et al., 2011), elevated sodium concentrations at the cytoplasmic side of the membrane will augment efflux triggered by substrates but not blockers (Bonisch, 1986, Sitte and Freissmuth, 2010). At all MATs included in our study, the co-application of monensin and 2-, 3- or 4-FPM resulted in a significantly higher fractional release of tritiated substrate in comparison to that observed in the absence of monensin (Figure 3).

It is noteworthy that 2-, 3- and 4-FPM exerted only small effects on SERT-mediated efflux when given without monensin (Figure 3 and supplementary Figure 1). Earlier studies showed that application of a transporter blocker might artificially enhance transporter mediated efflux (i.e., pseudo-efflux). Such an effect can be explained by the fact that an inhibitor prevents transporters from re-capturing extracellular [3H]substrates that leaked from the cells by simple diffusion (Scholze et al., 2000). In this manuscript, we provide two lines of evidence that rule out the possibility that FPMs might increase efflux [3H]5-HT via uptake blockade. First, as described above, co-application of monensin augmented the FPM-induced efflux several-fold (Figure 3), a phenomenon which clearly differentiates transportable substrates from non-transported inhibitors (Baumann et al., 2013, Sandtner et al., 2016, Mayer et al., 2017). Second, as observed for the endogenous SERT-substrate 5-HT, the presence of 2-, 3- and 4-FPM induced inwardly directed currents in SERT expressing cells (Figure 4). Together, these two data sets provide compelling evidence that the FPMs included in this study are transported by SERT in cell systems. It is worth mentioning that Scholze et al. (2000) demonstrated monensin causes (a) a rise in intracellular Na+ and (b) an alkalization of the interior of the cell. As such monensin is likely to i) increase transporter-mediated efflux, ii) enhance outward diffusion of the 5HT and iii) perhaps also diminish reuptake of 5-HT via SERT. The effective release rate in the presence of monensin will critically depend on the rate of 5HT reuptake which may or may not fully compensate for the enhanced release (diffusion or carrier-mediated). The reuptake rate is determined mostly by the amount of transporters expressed on the cell surface, which for HEK293 cells used in the current study is likely to be very high due to the use of an inducible expression system. It is probably for this reason that the apparent release induced by monensin alone in the present work is considerably lower than in the earlier study of Scholze and coworkers, where a different cell line was used. In synaptosomes prepared from native rat brain tissue, FPMs induced fully efficacious release of tritiated substrate in a concentration dependent manner via all three MATs. As stated above, this observation strongly supports the hypothesis that the effects of FPMs at DAT, NET and SERT involve reverse transport rather than simple uptake blockade. In accordance with uptake inhibition assays performed in HEK293 cells, a shift to the right could be observed for the potencies of the isomers as releasers of [3H]5HT at SERT, when compared to potencies at DAT and NET. It is predicted that the effects of FPMs on transporter-mediated release of tritiated substrates by DAT, NET and SERT will be antagonized by uptake blockers at these sites, as seen for co-application of paroxetine and PCA in Scholze et al., 2000. Future studies should test this hypothesis with FPMs. Other investigators have subtracted nonspecific “pseudo-efflux” caused by uptake inhibitors from total release, and considered a drug as a 5-HT releaser only when it produced significantly higher maximal 5-HT efflux compared with citalopram (Simmler et al., 2013). Importantly, the present findings from synaptosomes show that ring-substitution at the 2-, 3- and 4-position produced an increase in the relative potency at SERT, i.e. reducing the DAT/SERT and NET/SERT ratios (Figure 5 and Table 2). Thus, the release experiments in synaptosomes agree with data from HEK293 cells which demonstrate that fluoro ring-substitution of phenmetrazine, especially at the 4-position, can increase potency at SERT relative to DAT or NET. This observation agrees with the findings published by Cozzi et al., (2013) who tested the effects of trifluoromethyl ring-substituted methcathinone analogs (Cozzi et al., 2013), showing that substitution at the 2-,3- and 4-positions shift the relative potencies of test drugs towards the SERT.

The release assays carried out in synaptosome preparations were performed in the presence of reserpine to block vesicular accumulation of tritiated substrates, and to exclusively observe the effects of the fluorinated phenmetrazines on DAT, NET and SERT. Partilla and colleagues have shown that the parent drug phenmetrazine does not interact with the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) as an inhibitor or substrate at concentrations up to 100 μM (Partilla et al., 2006). Thus, it seems unlikely that the fluorinated phenmetrazine analogues tested here would differ in this respect. Nevertheless, future studies are warranted to examine the effects of FPMs and other NPS on VMAT2 function.

In this study, no in vivo experiments were performed, and extrapolation of in vitro findings to possible effects in animals or humans must be made with caution. For example, it was previously shown (Rothman et al., 2002) that systemic administration of phenmetrazine results in dose-related elevations of extracellular dopamine and serotonin in rat nucleus accumbens, despite the fact that in vitro findings indicate phenmetrazine is at least 10-fold DAT-selective compared to SERT. The present in vitro data show that fluorination at the 2- or 3-position of phenmetrazine did not have a major impact on MAT activity as compared to the parent compound phenmetrazine. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that 3-FPM will have in vivo effects that mimic those of phenmetrazine itself. Indeed, user reports found on Internet forums (e.g. erowid.org, drugs-forum or bluelight.org) indicate 3-FPM produces psychostimulant-like subjective effects in recreational human users. A recent publication by Backberg et al. (Backberg et al., 2016) showed that 3-FPM was found in serum and urine of drug abusers seeking medical care. In the cases reported by Backberg et al., stimulant-like neurobiological effects seem consistent with the MAT activity of 3-FPM reported here, but this interpretation is complicated by polydrug abuse of the individuals included in that study (Backberg et al., 2016). Controlled studies would be needed to assess the clinical effects in more detail. In addition, no data for potential activity at receptors are available for the phenmetrazines examined in this study. For instance, a previous study conclusively demonstrated that the psychoactive properties of methcathinone analogs are attributable to their activities at MATs and not at receptors (Simmler et al., 2014). Future studies should examine the receptor activities for FPM isomers. The data described in this study predict that all three phenmetrazine isomers will exert similar effects at DAT and NET, which could contribute to significant risk for abuse and addiction. In this study, we also included the 2- and 4-FPM isomers which have yet to appear as “research chemicals”. Given the fluid nature of the NPS phenomenon and the changes associated with “catch-up” legislation (Brandt et al., 2014), the appearance of 3-FPM analogues and its isomers cannot be fully excluded.

5. Conclusion

The “research chemical” 3-FPM, and its two positional isomers 2-FPM and 4-FPM, have been identified as substrate-type releasing agents at MATs. All of the FPM isomers are more selective for DAT and NET as compared to SERT, indicating a high potential for abuse and addiction. However, movement of the ring-substitution from the 2-, to 3- to 4-position produced an increase in the relative potency at SERT, i.e. reducing the DAT/SERT and NET/SERT ratios. This study has characterized the molecular mechanism of action of a current NPS and two positional isomers that could appear as replacements in response to banning of 3-FPM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by Austrian Research Fund/FWF grants F3506 and W1232 (H.H.S.) and DA12970 (B.E.B.); F.P.M. is a recipient of a DOC-fellowship of the Austrian Academy of Sciences; Portions of the work were supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, USA (J.S.P and M.H.B.).

Abbreviations

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- DA

dopamine

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- FPM

fluorophenmetrazine

- HEK293 cells

human emrbyonic kidney cells

- KHB

Krebs-HEPES-buffer

- MAT

monoamine transporter

- MPP+

1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium

- NET

norepinephrine transporter

- NPS

new psychoactive substance

- SERT

serotonin transporter

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

HHS has received honoraria for lectures and consulting from AbbVie, Lundbeck, MSD, Ratiopharm, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis and Serumwerk Bernburg (past 5 years). All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References:

- BACKBERG M, WESTERBERGH J, BECK O & HELANDER A 2016. Adverse events related to the new psychoactive substance 3-fluorophenmetrazine - results from the Swedish STRIDA project. Clin Toxicol (Phila), 54, 819–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANKS ML, BLOUGH BE, FENNELL TR, SNYDER RW & NEGUS SS 2013. Role of phenmetrazine as an active metabolite of phendimetrazine: evidence from studies of drug discrimination and pharmacokinetics in rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend, 130, 158–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAUMANN MH, AYESTAS MA JR., PARTILLA JS, SINK JR, SHULGIN AT, DALEY PF, BRANDT SD, ROTHMAN RB, RUOHO AE & COZZI NV 2012. The designer methcathinone analogs, mephedrone and methylone, are substrates for monoamine transporters in brain tissue. Neuropsychopharmacology, 37, 1192–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAUMANN MH, CLARK RD, WOOLVERTON WL, WEE S, BLOUGH BE & ROTHMAN RB 2011. In vivo effects of amphetamine analogs reveal evidence for serotonergic inhibition of mesolimbic dopamine transmission in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 337, 218–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAUMANN MH, PARTILLA JS, LEHNER KR, THORNDIKE EB, HOFFMAN AF, HOLY M, ROTHMAN RB, GOLDBERG SR, LUPICA CR, SITTE HH, BRANDT SD, TELLA SR, COZZI NV & SCHINDLER CW 2013. Powerful cocaine-like actions of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), a principal constituent of psychoactive ‘bath salts’ products. Neuropsychopharmacology, 38, 552–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAUMANN MH, SOLIS E JR., WATTERSON LR, MARUSICH JA, FANTEGROSSI WE & WILEY JL 2014. Baths salts, spice, and related designer drugs: the science behind the headlines. J Neurosci, 34, 15150–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLOUGH BER, NC, US), ROTHMAN RICHARD (ELLICOTT CITY, MD, US), LANDAVAZO ANTONIO (RALEIGH, NC, US), PAGE KEVINM (WILLOW SPRING, NC, US), DECKER ANNMARIE (DURHAM, NC, US). 2013. Phenylmorpholines and analogues thereof. United States patent application 20130203752.

- BLOUGH BETFR, RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA, 27607, US), ROTHMAN RICHARD (12719 FOLLY QUARTER ROAD, ELLICOTT CITY, MARYLAND, 21042, US), LANDAVAZO ANTONIO (2313 FALLS RIVER AVENUE, RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA, 27614, US), PAGE KEVINM (264 MICHAEL PLACE, WILLOW SPRING, NORTH CAROLINA, 27592, US), DECKER ANNMARIE (1300 LAUREL SPRINGS DRIVE, DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA, 27713, US). 2011. Phenylmorpholines and analogues thereof. WO/2011/146850.

- BONISCH H 1986. The role of co-transported sodium in the effect of indirectly acting sympathomimetic amines. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol, 332, 135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRANDT SD, ELLIOTT SP, KAVANAGH PV, DEMPSTER NM, MEYER MR, MAURER HH & NICHOLS DE 2015. Analytical characterization of bioactive N-benzyl-substituted phenethylamines and 5-methoxytryptamines. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom, 29, 573–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRANDT SD, KING LA & EVANS-BROWN M 2014. The new drug phenomenon. Drug Test Anal, 6, 587–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COZZI NV, BRANDT SD, DALEY PF, PARTILLA JS, ROTHMAN RB, TULZER A, SITTE HH & BAUMANN MH 2013. Pharmacological examination of trifluoromethyl ring-substituted methcathinone analogs. Eur J Pharmacol, 699, 180–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DINGER J, WOODS C, BRANDT SD, MEYER MR & MAURER HH 2016. Cytochrome P450 inhibition potential of new psychoactive substances of the tryptamine class. Toxicol Lett, 241, 82–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLIOTT SP, BRANDT SD, FREEMAN S & ARCHER RP 2013. AMT (3-(2-aminopropyl)indole) and 5-IT (5-(2-aminopropyl)indole): an analytical challenge and implications for forensic analysis. Drug Test Anal, 5, 196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAY EG & WHITTAKER VP 1962. The isolation of nerve endings from brain: an electron-microscopic study of cell fragments derived by homogenization and centrifugation. J Anat, 96, 79–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIFFITHS RR, WINGER G, BRADY JV & SNELL JD 1976. Comparison of behavior maintained by infusions of eight phenylethylamines in baboons. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 50, 251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEAL DJ, GOSDEN J & SMITH SL 2014. Dopamine reuptake transporter (DAT) “inverse agonism”--a novel hypothesis to explain the enigmatic pharmacology of cocaine. Neuropharmacology, 87, 19–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILBER B, SCHOLZE P, DOROSTKAR MM, SANDTNER W, HOLY M, BOEHM S, SINGER EA & SITTE HH 2005. Serotonin-transporter mediated efflux: a pharmacological analysis of amphetamines and non-amphetamines. Neuropharmacology, 49, 811–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRISTENSEN AS, ANDERSEN J, JORGENSEN TN, SORENSEN L, ERIKSEN J, LOLAND CJ, STROMGAARD K & GETHER U 2011. SLC6 neurotransmitter transporters: structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacol Rev, 63, 585–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGER S, MIN C, HENRY DJ, CHAVKIN C, HOFFMAN BJ, DAVIDSON N & LESTER HA 1994. Conducting states of a mammalian serotonin transporter. Neuron, 12, 845–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARONA-LEWICKA D, RHEE GS, SPRAGUE JE & NICHOLS DE 1995. Psychostimulant-like effects of p-fluoroamphetamine in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol, 287, 105–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARUSICH JA, ANTONAZZO KR, BLOUGH BE, BRANDT SD, KAVANAGH PV, PARTILLA JS & BAUMANN MH 2016. The new psychoactive substances 5-(2-aminopropyl)indole (5-IT) and 6-(2-aminopropyl)indole (6-IT) interact with monoamine transporters in brain tissue. Neuropharmacology, 101, 68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAYER FP, LUF A, NAGY C, HOLY M, SCHMID R, FREISSMUTH M & SITTE HH 2017. Application of a Combined Approach to Identify New Psychoactive Street Drugs and Decipher Their Mechanisms at Monoamine Transporters. Curr Top Behav Neurosci, 32, 333–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLAUGHLIN G, MORRIS N, KAVANAGH PV, POWER JD, O’BRIEN J, TALBOT B, ELLIOTT SP, WALLACH J, HOANG K, MORRIS H & BRANDT SD 2016. Test purchase, synthesis, and characterization of 2-methoxydiphenidine (MXP) and differentiation from its meta- and para-substituted isomers. Drug Test Anal, 8, 98–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOLLENHAUER HH, MORRE DJ & ROWE LD 1990. Alteration of intracellular traffic by monensin; mechanism, specificity and relationship to toxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1031, 225–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGAI F, NONAKA R & SATOH HISASHI KAMIMURA K 2007. The effects of non-medically used psychoactive drugs on monoamine neurotransmission in rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol, 559, 132–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARTILLA JS, DEMPSEY AG, NAGPAL AS, BLOUGH BE, BAUMANN MH & ROTHMAN RB 2006. Interaction of amphetamines and related compounds at the vesicular monoamine transporter. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 319, 237–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PLENGE P, SHI L, BEUMING T, TE J, NEWMAN AH, WEINSTEIN H, GETHER U & LOLAND CJ 2012. Steric hindrance mutagenesis in the conserved extracellular vestibule impedes allosteric binding of antidepressants to the serotonin transporter. J Biol Chem, 287, 39316–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RICKLI A, HOENER MC & LIECHTI ME 2015. Monoamine transporter and receptor interaction profiles of novel psychoactive substances: para-halogenated amphetamines and pyrovalerone cathinones. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol, 25, 365–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBERTSON SD, MATTHIES HJ & GALLI A 2009. A closer look at amphetamine-induced reverse transport and trafficking of the dopamine and norepinephrine transporters. Mol Neurobiol, 39, 73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROTHMAN RB, KATSNELSON M, VU N, PARTILLA JS, DERSCH CM, BLOUGH BE & BAUMANN MH 2002. Interaction of the anorectic medication, phendimetrazine, and its metabolites with monoamine transporters in rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol, 447, 51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANDTNER W, STOCKNER T, HASENHUETL PS, PARTILLA JS, SEDDIK A, ZHANG YW, CAO J, HOLY M, STEINKELLNER T, RUDNICK G, BAUMANN MH, ECKER GF, NEWMAN AH & SITTE HH 2016. Binding Mode Selection Determines the Action of Ecstasy Homologs at Monoamine Transporters. Mol Pharmacol, 89, 165–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHOLZE P, NORREGAARD L, SINGER EA, FREISSMUTH M, GETHER U & SITTE HH 2002. The role of zinc ions in reverse transport mediated by monoamine transporters. J Biol Chem, 277, 21505–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHOLZE P, ZWACH J, KATTINGER A, PIFL C, SINGER EA & SITTE HH 2000. Transporter-mediated release: a superfusion study on human embryonic kidney cells stably expressing the human serotonin transporter. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 293, 870–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMMLER LD, BUSER TA, DONZELLI M, SCHRAMM Y, DIEU LH, HUWYLER J, CHABOZ S, HOENER MC & LIECHTI ME 2013. Pharmacological characterization of designer cathinones in vitro. Br J Pharmacol, 168, 458–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMMLER LD, RICKLI A, HOENER MC & LIECHTI ME 2014. Monoamine transporter and receptor interaction profiles of a new series of designer cathinones. Neuropharmacology, 79, 152–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SITTE HH & FREISSMUTH M 2010. The reverse operation of Na(+)/Cl(−)-coupled neurotransmitter transporters--why amphetamines take two to tango. J Neurochem, 112, 340–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SITTE HH & FREISSMUTH M 2015. Amphetamines, new psychoactive drugs and the monoamine transporter cycle. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 36, 41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SITTE HH, SCHOLZE P, SCHLOSS P, PIFL C & SINGER EA 2000. Characterization of carrier-mediated efflux in human embryonic kidney 293 cells stably expressing the rat serotonin transporter: a superfusion study. J Neurochem, 74, 1317–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOLIS E JR., SUYAMA JA, LAZENKA MF, DEFELICE LJ, NEGUS SS, BLOUGH BE & BANKS ML 2016. Dissociable effects of the prodrug phendimetrazine and its metabolite phenmetrazine at dopamine transporters. Sci Rep, 6, 31385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SULZER D, SONDERS MS, POULSEN NW & GALLI A 2005. Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: a review. Prog Neurobiol, 75, 406–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TETTEY J & CREAN C 2015. New psychoactive substances: catalysing a shift in forensic science practice? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TORRES GE, GAINETDINOV RR & CARON MG 2003. Plasma membrane monoamine transporters: structure, regulation and function. Nat Rev Neurosci, 4, 13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VENTON BJ, SEIPEL AT, PHILLIPS PE, WETSEL WC, GITLER D, GREENGARD P, AUGUSTINE GJ & WIGHTMAN RM 2006. Cocaine increases dopamine release by mobilization of a synapsin-dependent reserve pool. J Neurosci, 26, 3206–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WELTER-LUEDEKE J & MAURER HH 2016. New Psychoactive Substances: Chemistry, Pharmacology, Metabolism, and Detectability of Amphetamine Derivatives With Modified Ring Systems. Ther Drug Monit, 38, 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILHELM BG, MANDAD S, TRUCKENBRODT S, KROHNERT K, SCHAFER C, RAMMNER B, KOO SJ, CLASSEN GA, KRAUSS M, HAUCKE V, URLAUB H & RIZZOLI SO 2014. Composition of isolated synaptic boutons reveals the amounts of vesicle trafficking proteins. Science, 344, 1023–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Web- References

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.