Abstract

Age-related vascular endothelial dysfunction is a major antecedent to cardiovascular diseases. We investigated whether increased circulating levels of the gut microbiome-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide induces endothelial dysfunction with aging. In healthy humans, plasma trimethylamine-N-oxide was higher in middle-aged/older (64±7 years) vs. young (22±2 years) adults (6.5±0.7 vs.1.6±0.2μM) and inversely related to brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (r2=0.29, p<0.00001). In young mice, 6 months of dietary supplementation with trimethylamine-N-oxide induced an aging-like impairment in carotid artery endothelium-dependent dilation to acetylcholine vs. control feeding (peak dilation: 79±3% vs. 95±3%, p<0.01). This impairment was accompanied by increased vascular nitrotyrosine, a marker of oxidative stress, and reversed by the superoxide dismutase mimetic TEMPOL. Trimethylamine-N-oxide supplementation also reduced activation of endothelial NO synthase and impaired NO-mediated dilation, as assessed with the NO synthase inhibitor L-NAME. Acute incubation of carotid arteries with trimethylamine-N-oxide recapitulated these events. Next, treatment with 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol for 8–10 weeks to suppress trimethylamine-N-oxide selectively improved endothelium-dependent dilation in old mice to young levels (peak: 90±2%) by normalizing vascular superoxide production, restoring NO-mediated dilation and ameliorating superoxide-related suppression of endothelium-dependent dilation. Lastly, among healthy middle-aged/older adults, higher plasma trimethylamine-N-oxide was associated with greater nitrotyrosine abundance in biopsied endothelial cells, and infusion of the antioxidant ascorbic acid restored flow-mediated dilation to young levels, indicating tonic oxidative stress-related suppression of endothelial function with higher circulating trimethylamine-N-oxide. Using multiple experimental approaches in mice and humans, we demonstrate a clear role of trimethylamine-N-oxide in promoting age-related endothelial dysfunction via oxidative stress, which may have implications for prevention of cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: Aging, gut microbiome, endothelium, nitric oxide, superoxide, nitrotyrosine

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) increases exponentially with advancing age largely due to the development of vascular endothelial dysfunction1,2. Not only is endothelial dysfunction an initiating step in the progression towards clinical CVD1,3, but it also increases risk of various other age-associated diseases/disorders, including chronic kidney disease, metabolic disorders, cognitive impairment and dementia, and exercise intolerance4. As such, identifying effective interventions for preventing and/or treating age-related endothelial dysfunction is a major, but currently unmet, biomedical research goal1,5. A key factor limiting progress towards this goal is that the mechanisms driving endothelial dysfunction with aging remain incompletely understood. Excessive superoxide-associated oxidative stress, which reduces bioavailability of the vasoprotective and vasodilatory molecule nitric oxide (NO), plays a critical role6,7, but the upstream mechanisms driving this oxidative stress have not been established.

One possible link between aging, oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction is the gut microbiome, as indicated by recent findings from our laboratory showing that short-term suppression of the gut microbiome with antibiotics reverses endothelial dysfunction in old mice8. Our results also indicated a potential role of the gut-derived metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), which is produced through microbe-dependent conversion of ingested precursors (e.g., choline, betaine and L-carnitine) into trimethylamine (TMA; via TMA lyase) that is subsequently absorbed into circulation and converted to TMAO in the liver9,10. Increased plasma concentrations of TMAO independently predict future CVD11–13, are causally linked to the development of atherosclerosis in transgenic mouse models14,15, and are associated with several diseases in humans, including chronic kidney disease16, type II diabetes mellitus17, and Alzheimer’s disease18. However, whether TMAO contributes to endothelial dysfunction with aging and the underlying mechanisms have not yet been fully investigated. In particular, no information is presently available in humans.

Accordingly, here, in a series of well-controlled translational experiments using a comprehensive set of diverse models, functional assessments and mechanistic probes, we investigate the influence of TMAO on endothelial function with aging. We hypothesized that higher circulating concentrations of TMAO with aging or dietary supplementation would be associated with greater superoxide-driven oxidative stress, resulting in reduced NO bioavailability and endothelial dysfunction. We first show that plasma concentrations of TMAO are higher in healthy middle-aged and older (MA/O) humans compared with young adult controls, and that circulating TMAO is inversely related to endothelial function. Using a mouse model, we next show that supplementation with TMAO directly induces an “aging-like” impairment in endothelial function via superoxide-associated oxidative stress and impaired NO bioavailability. To confirm these effects of TMAO with aging, we then suppressed TMAO production in old mice with the gut-targeted TMA lyase inhibitor 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol (DMB), which reversed age-related endothelial dysfunction to levels observed in young mice via normalization of oxidative stress and NO bioavailability. Lastly, we show that the greater endothelial dysfunction in MA/O adults with higher plasma TMAO is associated with greater tonic oxidative stress-related suppression of endothelial function in vivo and evidence of greater oxidative stress in biopsied endothelial cells, supporting the notion that TMAO impairs endothelial function via similar mechanisms (i.e., superoxide-related oxidative stress) in mice and humans. Overall, our results may have important implications for the prevention of age-associated CVD.

METHODS

All data presented in this manuscript and in the online Supplemental Material will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Human subject’s experiments

Experiments involving human subjects were approved by the University of Colorado Boulder Institutional Review Board and complied with the principles set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Subjects were aged 18-27 years (young controls; N=22) or 50-79 years (MA/O; N=101) and had been enrolled in previously conducted intervention-based studies19–23. All subjects were healthy (free from overt clinical disease) based on medical history and physical examination. None of the subjects were physically trained. MA/O subjects had also undergone incremental treadmill testing with ECG and blood pressure to ensure the absence of overt heart disease. On a separate day, maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) was measured during incremental treadmill testing using open-circuit spirometry.

For vascular testing, subjects had been studied either at baseline (prior to the start of the intervention for parallel-design studies; N=70) or at the end of a placebo phase (for crossover design studies, N=47; of these, only N=19 subjects were assigned to receive the placebo second, after the experimental intervention, and no carry over effects on FMD were observed for any intervention19,21,23). All subjects had been studied following an 8–12-hour overnight fast, >20 hours without alcohol, caffeine or vigorous physical activity, and >48 hours without dietary supplements or over-the-counter medications. Subjects refrained from taking prescription medications the morning of testing. Body mass and height were determined by anthropometry; body mass index was calculated. Arterial blood pressure was measured in triplicate over the brachial artery (arm supported at heart level) during seated rest using a semiautomated device (Dinamap XL, Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ). Venous blood was collected for analysis of lipid and lipoprotein concentrations in a CLIA certified laboratory (Boulder Community Hospital Clinical Laboratory, Boulder, CO). An additional plasma sample was stored for later analysis of TMAO, choline, betaine and L-carnitine by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using a stable isotope dilution method against internal standards, as previously described24–26. Three-day diet records were also analyzed from a subset of young and MA/O subjects (N=13/age group) to determine dietary intake of choline, betaine and L-carnitine. Investigators were blinded to subject age and characteristics for plasma and dietary intake analyses. Vascular endothelial function was assessed by brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMDBA), in accordance with established guidelines27. To assess oxidative stress-related suppression of endothelial function, in a subset of subjects (young: N=14; MA/O: N=27), FMDBA was measured following a 20-min intravenous infusion of saline (volume control) and following a 20-min infusion of the reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenger ascorbic acid19,28. Vascular endothelial cells were collected from an antecubital vein by J-wire technique, fixed on slides, and stained to quantify abundance of protein markers of oxidative stress and inflammation by immunofluorescence29,30. Further details on all procedures and antibodies used are included in the Supplemental Material.

Animal experiments

All animal protocols were approved by the University of Colorado Boulder Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and complied with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. A total of 124 male C57BL/6N mice were obtained for these studies from Charles River (young mice; received at 8 weeks of age) or from the National Institute on Aging colony maintained by Charles River (old mice; received at 20–24 months of age). All mice were housed in a conventional facility on a 12-hour light/dark cycle, given ad libitum access to rodent chow and drinking water, and allowed to acclimate to our facility for at least 4 weeks prior to the start of any testing. Mice were single-housed for the duration of all interventions in order to prevent mouse-to-mouse effects on the gut microbiome.

All mice were sacrificed by exsanguination while maintained under anesthesia (inhaled isoflurane). Blood was centrifuged and separated, and heparinized plasma was stored frozen at −80°C for later analysis of TMAO, choline, betaine and L-carnitine, as described above. Carotid arteries were excised, dissected free of surrounding tissue and cannulated in pressurized myograph chambers (DMT, Inc.; Aarhus, Demark) to assess endothelium-dependent dilation (EDD) to increasing doses of acetylcholine (ACh; 10−9 to 10−4 M; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO) and endothelium-independent dilation to increasing doses of the NO donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP; 10−10 to 10−4 M; Sigma-Aldrich Corp.), as previously described8,31,32. Further details, including all pharmacological agents used for pharmaco-dissection, are provided in the Supplemental Material. The thoracic aorta was excised, dissected free of surrounding tissue, sectioned and stored appropriately for later assessment of protein abundance by Western immunoblotting and immunofluorescence, and concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines. For the DMB treatment study, 1–2 sections 1 mm in length were immediately used for assessment of superoxide production by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. All investigators were blinded to treatment group for data collection and plasma and biochemical analyses. Details on all procedures, antibodies and kits used are provided in the Supplemental Material.

TMAO supplementation.

Beginning at 6 months of age, young mice (N=12/group) were randomly fed a defined-choline diet (0.07%; to control for dietary TMAO precursors) without or with 0.12% TMAO added9 (customized diet from Envigo, Madison, WI; TMAO, Sigma-Aldrich, Corp.) for 6 months and sacrificed at 12 months of age. Two mice (1/group) died during the intervention for reasons unrelated to the current study. As such, N=11/group were studied and included in final analyses.

DMB supplementation.

Young (3 months; N=12/group) and old (24 months; N=26-29/group; starting group sizes doubled to account for up to 50% attrition) mice were fed a standard chow diet (Envigo) and randomized to receive ad libitum access to either normal drinking water (Control) or drinking water supplemented with 1% (v/v) 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol (DMB; Sigma-Aldrich) for 8-10 weeks14. Mice were sacrificed at 5-6 (young) or 26-27 months (old) of age. All young mice survived the full intervention and were studied; N=20/group old mice survived and were studied.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in Prism, version 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) and R, version 3.6.2 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was set to α=0.05. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M., unless otherwise noted. Detailed descriptions of all statistical approaches are provided in the Supplemental Material.

RESULTS

Plasma TMAO increases with aging and is inversely related to endothelial function

Plasma TMAO.

Fasted plasma concentrations of TMAO and related metabolites were measured by LC-MS/MS25,26 in young (age 18–27; N=22) and middle-aged to older (MA/O; age 50–79; N=101) adults free of overt clinical disease. Subject characteristics are provided in Table 1. The types of medications used and number of subjects taking those agents are provided in Supplemental Table S1 and were typical of healthy young and older populations. Circulating (plasma) TMAO concentrations were higher in MA/O vs. young adults (non-transformed values: Figure 1A; p<0.001; log-transformed to account for skewness: young, 0.5±0.7 vs. MA/O, 1.6±0.7 μM, p<0.001). Plasma concentrations of the TMAO precursor choline (p<0.001) were also higher in MA/O vs. young adults, but no differences were observed in plasma L-carnitine (p=0.19) or betaine (p=0.41). There were no differences in dietary intake of choline, betaine or L-carnitine between young and MA/O subjects (all p>0.40), suggesting that the age-related differences in plasma TMAO and choline were not obviously due to altered dietary intake of TMAO precursors. Plasma concentrations and dietary intake of precursors of TMAO are provided in Supplemental Table S2.

Table 1.

Human subject characteristics

| Subject Characteristic | Young (N=22) | MA/O (N=101) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 22 ± 2 | 64 ± 7* |

| Male/female | 10/11 | 45/56 |

| Body mass (kg) | 68 ± 9 | 70 ± 15 |

| Height (cm) | 172 ± 9 | 170 ± 9 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.8 ± 2.1 | 24.0 ± 3.9 |

| VO2max (ml/min/kg) | 46.2 ± 9.3 | 30.7 ± 5.6* |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 107 ± 8 | 122 ± 14* |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 65 ± 10 | 72 ± 8* |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 154 ± 28 | 180 ± 32* |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 83 ± 24 | 107 ± 26* |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 55 ± 19 | 58 ± 19 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 84 ± 43 | 90 ± 46 |

| Fasted blood glucose (mg/dl) | 78 ± 10 | 86 ± 8* |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 95 ± 11 | 77 ± 15* |

Data are mean ± S.D. Young: age 18–27; Middle-aged to older (MA/O): age 50-79.

p<0.05 vs. young. Glomerular filtration rate estimated with MDRD equation based on serum creatinine, age, sex and race.

Figure 1. Plasma concentrations of trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) are inversely related to conduit artery endothelial function in healthy adults varying in age.

Plasma TMAO (A) and endothelial function (B; assessed by brachial artery flow-mediated dilation [FMDBA]) in young (N=19) and middle-aged to older (MA/O; N=98) adults. Data are mean ± S.E.M. *p<0.05 vs. young adults (unpaired t-test). C) The unadjusted relation between plasma TMAO (log transformed due to skewness) and FMDBA. D) The adjusted partial residual scatterplot between the Ln TMAO and FMDBA residuals calculated from the linear model adjusted for age, sex, and cardiovascular risk factors (see text), with 95% confidence intervals for the fitted values (grey shaded area). This plot illustrates the strength of the independent effect of TMAO on FMDBA.

Vascular Endothelial Function.

Endothelial function was measured in the MA/O adults (N=98) and in a subset of young adults (N=19) as a reference group. Endothelial function, as assessed by FMDBA, was significantly lower in the MA/O vs. young adults (p<0.0001; Figure 1B). There were no differences in baseline brachial artery diameter (p=0.70) or endothelium-independent dilation to glycerol trinitrate (p=0.25) between young and MA/O adults (Supplemental Table S3).

We used regression analysis to determine if endothelial function was related to circulating TMAO concentrations across young and MA/O adults. TMAO values were log transformed due to skewness. We found that FMDBA was inversely related to plasma concentrations of TMAO (r2 = 0.29, p<0.00001; Figure 1C). This relation remained significant when the model was adjusted for age and sex (partial r2 for an independent effect of TMAO = 0.10, p<0.0001), as well as when the model was adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2max), systolic blood pressure, serum total cholesterol, serum low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and fasted blood glucose (partial r2 for TMAO = 0.09, p<0.0001; Figure 1D), indicating that circulating concentrations of TMAO predict endothelial dysfunction independent of traditional CVD risk factors. Moreover, the 9% of the variance in FMDBA explained independently by circulating TMAO was greater than any other CVD risk factor other than age (partial r2 = 0.16). The next strongest independent predictor, LDL cholesterol, explained only 6% of the variance in FMDBA (partial r2 = 0.06). There were no sex differences observed in the relation between TMAO and FMDBA (TMAO x sex interaction: p=0.42).

Lastly, as 13 MA/O subjects (out of 101) were taking one or more anti-hypertensive medications, we also adjusted the full model for the number of different types of anti-hypertensive medications that subjects were taking. The independent effect of TMAO on FMDBA remained significant (partial r2 = 0.09, p<0.01) and there was no effect of anti-hypertensive medication use (partial r2 < 0.01, p=0.90). Further, plasma TMAO values were not different in MA/O individuals taking anti-hypertensive medications vs. those who were not (6.4±6.6 vs. 6.7±7.1 μM, respectively, p=0.90). These results indicate that the relations we observed between age-associated changes in plasma TMAO and FMDBA are not influenced by anti-hypertensive medication use.

Chronic dietary supplementation with TMAO impairs endothelial function in young mice by increasing superoxide-associated oxidative stress

We have previously shown that plasma concentrations of TMAO are also higher in old (26–28 months) vs. young (6–8 months) male C57BL/6N mice8. As such, young (6 months) male C57BL/6N mice were fed a defined-choline (0.07%) diet, supplemented without (Control; N=9) or with 0.12% TMAO (N=11) for 6 months. Plasma concentrations of TMAO were significantly increased in mice supplemented with TMAO (31.5 ± 9.5 μM) compared to Controls (2.9 ± 0.4 μM, p<0.05), but there were no effects of TMAO supplementation on plasma concentrations of dietary precursors of TMAO (all p>0.45; Supplemental Table S4). TMAO supplementation did not affect body mass, food intake or mass of key organs (all p>0.27; Supplemental Table S4).

Vascular Endothelial Function and NO Bioavailability.

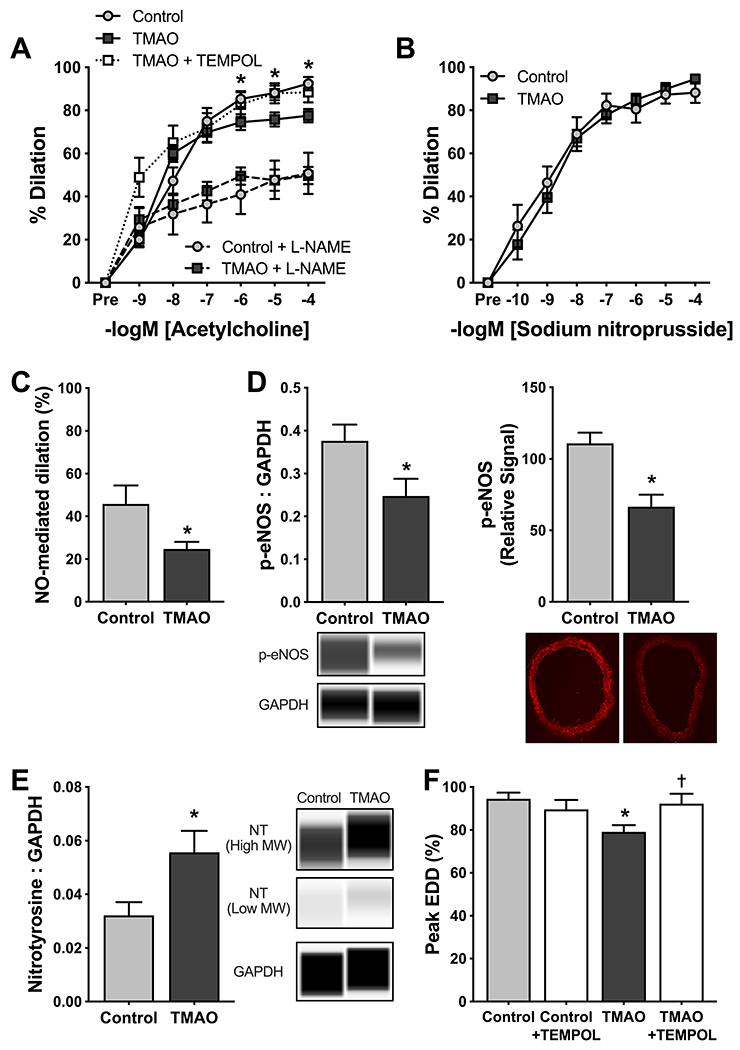

Carotid artery EDD to increasing doses of ACh was significantly lower in the chronically TMAO-supplemented group (Figure 2A; peak EDD, Control: 95±3% vs. TMAO: 79±3%, p<0.01). Impairments in EDD can be mediated by either reduced vascular smooth muscle cell sensitivity to NO and/or by reduced endothelial-derived NO bioavailability. To address the former, we assessed carotid artery endothelium-independent dilation to increasing doses of the NO donor SNP and observed no differences between the groups (Figure 2B), indicating impairments in EDD with TMAO must have been endothelial-specific. To assess whether TMAO impairs EDD by reducing NO bioavailability, we repeated dose responses to ACh following incubation with the NO synthase inhibitor NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME). L-NAME attenuated EDD to ~50% of maximal dilation in both Control and TMAO-supplemented mice (Figure 2A), such that NO-mediated dilation, as assessed by the difference between peak EDD in the absence vs. presence of L-NAME, was significantly lower in mice supplemented with TMAO vs. Controls (Figure 2C; p<0.05).

Figure 2. Chronic TMAO supplementation induces aging-like endothelial dysfunction via reduced NO bioavailability and increased superoxide-driven oxidative stress in young mice.

In arteries from young adult mice (12 mo.) supplemented without (Control) or with 0.12% trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) for 6 months: A) Carotid artery endothelium-dependent dilation (EDD) to increasing doses of acetylcholine (ACh) in the absence and presence of the nitric oxide (NO) synthase inhibitor NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME); B) Peak carotid artery endothelium-independent dilation to increasing doses of the NO donor sodium nitroprusside; C) NO-mediated dilation, as assessed by the difference in carotid artery peak EDD in the absence vs. presence of L-NAME; (D) Protein abundance of phosphorylated endothelial nitric oxide synthase (p-eNOS) at Ser1177, assessed by both Western blotting in aorta lysates (left panel; normalized to GAPDH with representative Western blot images generated from WES electropherograms shown below) and immunofluorescence in aorta rings (right panel; representative images show below); and (E) abundance of nitrotyrosine (sum of high and low molecular weight residues normalized to GAPDH with representative Western blot images generated from WES electropherograms shown to the right); and F) Carotid artery peak EDD to ACh in the absence and presence of the superoxide dismutase mimetic 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl (TEMPOL). All data are mean ± S.E.M. N=6–10/group. *p<0.05 TMAO vs. Control (panel A: 2-way mixed design ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc; panels C-F: unpaired t-test). †p<0.05 vs. ACh alone in TMAO-treated mice (paired t-test).

Reduced NO Bioavailability: Mechanisms of Action.

Reductions in bioavailability of NO can be mediated by lower production of NO via endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) and/or increased scavenging of NO by excessive superoxide bioactivity. First, we found that abundance of phosphorylated eNOS at Ser1177, a well-established marker of eNOS activation, was lower in aorta lysates from TMAO-supplemented mice vs. Controls (Figure 2D; both p<0.05), consistent with the possibility of reduced NO production. We then determined that abundance of nitrotyrosine, an indicator of oxidant modification of tyrosine residues on proteins and a well-established marker of oxidative stress, was ~2-fold higher in aortas from TMAO vs. Control mice (Figure 2E; p<0.05). Finally, to confirm an effect of superoxide-driven scavenging of NO on endothelial function, we repeated dose responses to ACh following incubation with the superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl (TEMPOL). TEMPOL restored EDD in carotid arteries from TMAO-supplemented mice to levels observed in the Control group (p<0.05) but had no effect on EDD in arteries from Control mice (Figure 2F). Together, these findings indicate that TMAO impairs EDD and NO bioavailability by increasing superoxide-dependent scavenging of NO, as well as possibly reducing NO production by eNOS.

Oxidative Stress-Related Mechanisms.

We next attempted to provide insight into the factors contributing to the effects of dietary TMAO supplementation on vascular oxidative stress. We first measured abundance of the superoxide-producing enzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase and both phosphorylated and total p66 Shc1, a marker and master regulator of mitochondrial ROS production, in aorta lysates, observing no differences between TMAO-supplemented vs. Control mice (Supplemental Figure S1A–C). Next we showed that TMAO supplementation had no effect on abundance of the superoxide-scavenging antioxidant enzymes copper-zinc (Cu/Zn)SOD (SOD1; cytosolic isoform; p=0.91), manganese (Mn)SOD (SOD2; mitochondrial isoform; p=0.77) or extracellular (ec)SOD (SOD3; p=0.66) (Supplemental Figure S1D–F). Lastly, because it has been reported that high doses of TMAO (~100μM) following acute intraperitoneal injection in mice and in cell culture may stimulate the pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative stress transcription factor nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB)33, we measured abundance of phosphorylated (i.e., activated) NFκB in aortic lysates. Contrary to findings by other groups, chronic dietary supplementation of TMAO did not influence aortic NFκB activation (p=0.97 Control vs. TMAO-supplemented mice; Supplemental Figure S2A). Consistent with this observation, we also observed no effect of TMAO supplementation on pro-inflammatory cytokines measured in aorta lysates, including interleukin (IL)-6, interferon (IFN)-γ, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (Supplemental Figure S2B–H). Overall, our results indicate that chronically elevated circulating levels of TMAO impair vascular endothelial function by promoting superoxide-driven oxidative stress in the absence of overt increases in pro-inflammatory signaling and cytokine expression. Our findings also indicate that TMAO supplementation-induced stimulation of oxidative stress and tonic superoxide suppression of endothelial function (EDD) are not obviously associated with increased expression of NADPH oxidase, mitochondrial superoxide production or SOD-related endogenous antioxidant defenses.

TMAO directly impairs endothelial function in isolated arteries of young mice

To demonstrate that the endothelial dysfunction induced by chronic dietary TMAO supplementation may have been mediated in part by direct effects of TMAO on the arteries, EDD was assessed in excised carotid arteries from a separate group of young adult male C57BL/6N mice (3–10 months; N=11) before and after a 60-min incubation with 25μM, 50μM or 100μM TMAO. A concentration of 25 μM TMAO was selected to match mean plasma concentrations obtained in the present study following chronic supplementation with TMAO. Two higher concentrations (50μM and 100μM) were also used, as we expected a larger concentration of TMAO would be needed to induce a similar magnitude of endothelial dysfunction within 60 minutes as was observed with chronic supplementation.

Pre-incubation with 25μM TMAO slightly, but significantly reduced EDD (peak EDD: p<0.05), whereas higher concentrations of TMAO decreased EDD in a dose-dependent fashion, such that peak EDD in the presence of 100μM TMAO was only 57±8% of the control response to ACh alone (p<0.01; Figure 3A–B). Consistent with what we observed with chronic TMAO supplementation, there was no effect of acute TMAO incubation on endothelium-independent dilation to SNP (peak, Control: 96±3% vs. 100μM TMAO: 97±2%, p=0.92; Figure 3C), indicating impairments in EDD with TMAO are endothelial-specific rather than due to effects of TMAO on smooth muscle sensitivity to NO.

Figure 3. Acute TMAO incubation directly induces endothelial dysfunction in isolated arteries.

A) Endothelium-dependent dilation (EDD) to increasing doses of acetylcholine (ACh) before (ACh alone) and after 60 min pre-incubation with 25μM, 50μM or 100μM trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO). Statistics are pairwise comparisons of each concentration of TMAO on mean EDD (averaged across doses of ACh; i.e., main TMAO concentration effect). *p<0.05 vs. ACh alone. †p<0.05 vs. 25μM TMAO. #p<0.05 vs. 50μM TMAO. N=11. B) Peak EDD derived from the dose response curves presented in (A). C) Endothelium-independent dilation to sodium nitroprusside (SNP) in paired carotid arteries from the same mice pre-incubated without (SNP alone) or with 100μM TMAO. N=7. D-E) Peak EDD to ACh, either alone or following pre-incubation with 100μM TMAO and/or with the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) (D) or the superoxide dismutase mimetic TEMPOL (E). Both N=4. For B-D, *p<0.05 vs. ACh alone (RM ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc). ‡p<0.05 vs. TMAO. All data are mean ± S.E.M.

To determine whether TMAO induces direct impairment of ACh-stimulated EDD via reducing NO bioavailability, carotid artery dose responses to ACh were performed in this order (3 dose responses in the same arteries separated by 40–60 min): 1) with ACh alone; 2) following 30 min incubation with the NO synthase inhibitor L-NAME; and 3) following 60 min incubation with L-NAME + 100μM TMAO (Figure 3D). L-NAME inhibited ~55% of EDD to ACh alone, but no further reduction in EDD was observed with the addition of TMAO, indicating TMAO directly impairs EDD by reducing NO bioavailability.

To determine whether TMAO directly suppresses EDD and NO bioavailability via superoxide-related oxidative stress, serial dose responses to ACh were performed under the following conditions in the same arteries: 1) with ACh alone; 2) following 60 min incubation with 100μM TMAO; and 3) following 60 min incubation with 100μM TMAO + the SOD mimetic TEMPOL (Figure 3E). Inhibition of superoxide bioactivity with TEMPOL completely reversed the TMAO-induced impairment of EDD. This observation suggests that the impairment in endothelial function induced by chronic dietary supplementation with TMAO may have been mediated, at least in part, via direct suppression of NO-mediated EDD by superoxide-dependent oxidative stress.

Inhibition of TMAO with DMB reverses endothelial dysfunction and vascular oxidative stress with aging

To investigate whether increases in plasma TMAO concentrations contribute to endothelial dysfunction with aging, young (5–6 mo.) and old (26–27 mo.) male C57BL/6N mice were fed a normal chow diet for 8 weeks with their drinking water either supplemented with 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol (DMB; young, YDMB: N=12; old, ODMB: N=12) or not supplemented (Control; young, YC: N=12; old, OC: N=18). DMB inhibits microbial TMA lyase and prevents gut microbiota from converting choline and other precursors into TMA14, thereby suppressing circulating concentrations of TMAO. DMB reduced plasma TMAO in old mice (p=0.07 OC vs. ODMB) to levels observed in young mice (p=0.99 YC vs. ODMB) but had no effect on plasma TMAO levels in young mice (p=0.99 YC vs. YDMB) (Figure 4A). There were no group differences in circulating concentrations of any precursors of TMAO, including choline, betaine and L-carnitine (all p>0.27; Supplemental Table S4).

Figure 4. DMB treatment reverses age-related impairments in endothelial function.

In young (5-6 mo.) and old (26-27 mo.) mice supplemented without (YC, OC) or with (YDMB, ODMB) 1% 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol (DMB) for 8-10 weeks (unless otherwise noted, young: N=8-11/group; old: N=10-14/group): A) Plasma TMAO concentrations; B) (Left panel) Carotid artery endothelium-dependent dilation (EDD) to increasing doses of acetylcholine (ACh) in the absence and presence of the nitric oxide (NO) synthase inhibitor NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), and (right panel) carotid artery endothelium-independent dilation to increasing doses of the NO donor sodium nitroprusside; C) NO-mediated dilation, as assessed by the difference in peak EDD in the absence vs. presence of L-NAME; D) Abundance of phosphorylated (Ser1177) endothelial NO synthase (p-eNOS) in aorta rings, with representative images shown to the right; E) Superoxide production, measured in 1mm aorta rings by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, with representative tracings above; and F) Peak carotid artery EDD to ACh in the absence and presence of the superoxide dismutase mimetic 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl (TEMPOL) in old mice (N=6-14/group). All data are mean ± S.E.M. Statistics are pairwise comparisons across groups and/or drug condition (1-way [panels A, C-E] or 2-way mixed design [panels B and F] ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc). *p<0.05 OC vs. YC. †p<0.05 OC vs. ODMB. ‡p=0.07 OC vs. ODMB.

Animal characteristics.

DMB treatment was well-tolerated by both young and old mice. Old mice tended to drink more water per day on average than young mice (p=0.07), but water intake was not affected by DMB treatment (p>0.32). Food intake was not different across groups (main effect: p=0.89). There were no apparent side effects of DMB, as indicated by no differences in body mass across groups (main effect: p=0.37) nor differences between Control and DMB-treated mice within age groups in the mass of key organs or visceral fat (all p>0.26). Maximal carotid artery diameter was higher in old mice, but this was unaffected by DMB treatment. These data are summarized in Supplemental Table S5.

Vascular Endothelial Function and NO Bioavailability.

DMB treatment fully reversed age-related reductions in EDD to increasing doses of acetylcholine in isolated carotid arteries in old mice, with no effects in young mice (Figure 4B left). There were no group differences in endothelium-independent dilation to SNP (main effect of group: p=0.14; Figure 4B right), indicating DMB did not enhance EDD by increasing smooth muscle sensitivity to NO. Addition of the NO synthase inhibitor L-NAME abolished group differences in EDD (main effect: p=0.88), such that age-related reductions in NO-mediated dilation were restored to young levels in old mice treated with DMB (ODMB vs. OC: p<0.05; ODMB vs. YC: p=0.99; Figure 4C). Overall, these data indicate that suppression of TMAO production with DMB restores endothelial function in old mice by enhancing NO bioavailability.

eNOS Activation and Oxidative Stress.

These DMB-mediated improvements in NO bioavailability and endothelial function in old mice were accompanied by an ~50% restoration of age-related reductions in phosphorylated (Ser1177) eNOS abundance in aortas (Figure 4D), consistent with improved eNOS activation. We then assessed superoxide production in the aorta directly using electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. Superoxide production was ~60% greater in the old vs. young untreated mice, but DMB normalized superoxide production in the old animals (p=0.92 YC vs. ODMB), while having no effect on young mice (Figure 4E). To determine if the normalization of superoxide production by DMB in the old mice ameliorated vascular oxidative stress, we then measured nitrotyrosine in aortic lysates and found that DMB tended to reduce aortic nitrotyrosine (Supplemental Figure S3). Finally, to demonstrate that the DMB-mediated reductions in superoxide production and oxidative stress were responsible for restoring NO bioavailability and endothelial function in the old mice, we treated isolated carotid arteries with the SOD mimetic TEMPOL and assessed EDD in response to increasing doses of acetylcholine. The addition of TEMPOL restored EDD in OC mice to young control levels (Peak EDD in OC mice to ACh alone vs. with TEMPOL: p<0.01; Figure 4F) and abolished group differences in EDD (Peak EDD with TEMPOL, YC: 96±1%, YDMB: 90±5%, OC: 88±4%, ODMB: 92±2%, main effect: p=0.31). Overall, these data indicate that DMB supplementation improves NO-mediated endothelial function by both increasing NO production via eNOS and reducing NO scavenging by superoxide.

Concentrations of plasma TMAO are related to markers of endothelial oxidative stress in humans

Our initial studies in humans showed that plasma TMAO concentrations increase with aging in adults free of chronic clinical disease and that vascular endothelial function is inversely related to plasma TMAO in this population. Our mechanistic studies in mice then demonstrated that increases in TMAO via dietary supplementation, ex vivo administration and natural aging all impair NO-mediated endothelial function by inducing oxidative stress. Accordingly, in this final set of experiments we sought to connect differences in circulating TMAO concentrations to corresponding differences in oxidative stress-associated impairments in endothelial function with aging in humans.

To do so, first we assessed in vivo oxidative stress-mediated suppression of EDD via functional bioassay as the acute increase in FMDBA following supra-physiological intravenous infusion of the antioxidant ascorbic acid (vs. saline infusion). This approach was designed to simulate and translate our TEMPOL administration experiments in mice to healthy aging in humans. In young adults, there was no change in FMDBA between saline and ascorbic acid conditions (ΔFMDBA: 0.3±0.4%; p=0.41), consistent with the interpretation of a lack of tonic oxidative stress-associated suppression of endothelial function. In contrast, in MA/O adults, FMDBA increased in response to ascorbic acid infusion vs. saline (ΔFMDBA: 1.8±0.4%; p<0.0001), consistent with tonic oxidative stress inhibition of endothelial function with aging.

To determine if higher circulating TMAO concentrations are associated with and/or predict oxidative stress-induced impairments in endothelial function with aging, we then divided our MA/O cohort into subgroups with lower (<4.4μM) and higher (>4.5μM) plasma TMAO (median value in overall cohort of N=101 MA/O adults = 4.46μM). There were no significant differences in subject characteristics between the two subgroups besides plasma TMAO (Supplemental Table S6). Baseline brachial artery diameter was comparable across groups and between saline (control) and ascorbic acid conditions, and endothelium-independent dilation to glycerol trinitrate was not different between groups (Supplemental Table S7). As observed in the young subjects, FMDBA did not increase from saline control levels in response to ascorbic acid infusion in the MA/O subgroup with lower circulating TMAO concentrations (Figure 5A–B). However, FMDBA increased significantly from control levels in the MA/O subgroup with higher circulating TMAO concentrations (group x drug infusion interaction: p<0.01). This interaction remained significant when young subjects were omitted from the model and when the model was adjusted for CVD risk factors (see Supplemental Table S8 for results of all statistical analyses). These observations support the concept that higher circulating concentrations of TMAO are associated with greater tonic oxidative stress-suppression of endothelial function among healthy MA/O adult humans.

Figure 5. Endothelial oxidative stress and its suppression of vascular function with aging are associated with higher circulating trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO).

A) Brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMDBA) following 20-min intravenous infusion with saline or the antioxidant ascorbic acid in young adults (18-27 years; N=14) and middle-aged to older (MA/O; 50-79 years) adults with either lower (<4.4μM; N=11) or higher (>4.5μM; N=16) plasma TMAO. Statistics are pairwise comparisons (Sidak’s multiple comparison test) assessed following 2-way mixed design ANOVA (group x drug: p<0.01). *p<0.05 vs. young within drug condition. †p<0.05 saline vs. ascorbic acid within group. B) The change in FMDBA from saline control in response to ascorbic acid (AA) infusion, i.e., oxidative stress-mediated suppression of FMDBA. Statistics are pairwise comparisons (Tukey’s post-hoc test) assessed following 1-way ANOVA (main effect: p<0.01). *p<0.05 vs. young. ‡p<0.05 vs. MA/O adults with lower TMAO. C-D) Abundance of nitrotyrosine in biopsied endothelial cells from MA/O adults is higher in individuals with higher vs. lower plasma TMAO levels (C; N=11-12/group; representative fluorescent images shown on the right) and is related to higher plasma TMAO levels (D; r2 for the unadjusted model is shown; TMAO values are log-transformed due to skewness).

Finally, we sought to translate our findings in mice by determining if higher circulating concentrations of TMAO were linked to oxidative stress in vascular endothelial cells in healthy MA/O adults. To accomplish this, venous endothelial cells were collected via clinical endovascular biopsy from a subset of our MA/O subjects (see Supplemental Table S9 for subject characteristics) and stained for markers of oxidative stress, oxidant enzyme expression and pro-inflammatory signaling using quantitative fluorescence immunohistochemistry. Consistent with our observations in mice, we found that nitrotyrosine was more abundant in endothelial cells from individuals with higher (>4.5μM) vs. lower (<4.4μM) circulating TMAO levels (p<0.05; Figure 5C). Moreover, among all subjects, Ln plasma TMAO was positively related to endothelial cell nitrotyrosine abundance (unadjusted model: r2=0.27, p=0.01; Figure 5D; adjusted for age, sex, CV risk factors, serum triglycerides, and number of anti-hypertensive medications: Ln TMAO partial r2=0.39, p<0.05). Also in agreement with our findings in mice, there were no group differences in endothelial cell abundance of NADPH oxidase (lower TMAO: 0.82±0.31 A.U. vs. higher TMAO: 0.69±0.11 A.U., p=0.74) or the p65 subunit of NF-κB (lower TMAO: 0.26±0.03 A.U. vs. higher TMAO: 0.25±0.07 A.U., p=0.92). These findings confirm and translationally extend our observations in mice by establishing that higher circulating concentrations of TMAO are associated with greater oxidative stress in vascular endothelial cells of healthy MA/O humans.

DISCUSSION

Impaired vascular endothelial function with aging is mediated by declines in NO bioavailability secondary to excess superoxide-related oxidative stress6,7,34, but the upstream mechanisms that drive these events have not been elucidated. Here, using multiple models that span the translational spectrum, we demonstrated for the first time a clear role of higher circulating levels of the gut microbiome-derived metabolite TMAO in promoting aging-related oxidative stress-induced impairments in endothelial function.

Increases in plasma TMAO with aging

We first confirmed that concentrations of plasma TMAO are higher in healthy MA/O compared to young adults, consistent with previous reports24,35. These differences were observed without obvious changes in dietary intake of precursors of TMAO, indicating that TMAO concentrations may be higher with aging due to altered gut microbe-dependent conversion of precursors into TMA and/or altered conversion of TMA into TMAO in the liver. Indeed, in mice, we have previously shown that aging increases relative abundance of the TMA-producing microbial genus Desulfovibrio and increases hepatic protein levels of the TMA-converting enzyme flavin-like monooxygenase (FMO)38. Others have reported increases in relative abundance of microbial taxa that contain TMA-producing species in elderly humans (e.g., Proteobacteria, which includes Desulfovibrio, and Enterobacteriaceae)10,36–38. However, altered abundance of these higher-level taxa does not necessarily indicate that abundance of TMA-producing species within these taxa is altered. Moreover, the majority of these individuals were studied in assisted living facilities or hospitals. As such, investigations are needed to further assess potential changes in the gut microbiome with aging in free-living, healthy adults. As TMAO is cleared from circulation through the kidneys, it is also possible that age-related impairments in kidney function contribute in part to the higher plasma TMAO levels, although we did not observe any relation between plasma TMAO and estimated glomerular filtration rate within our cohort of healthy MA/O adults. Reduced clearance also may have contributed to the higher plasma concentrations of choline observed in the MA/O adults given the lack of difference in dietary choline intake compared with the young controls.

TMAO impairs vascular endothelial function with aging

Vascular endothelial dysfunction is a key antecedent to the development of clinical CVD with aging1,3. Indeed, FMDBA, the gold-standard measure of conduit artery endothelial function in humans, is independently predictive of future age-related CVD morbidity and mortality39,40. In the present study, we identified higher circulating levels of TMAO as a clear upstream driver of endothelial dysfunction. This finding was consistent across multiple models, including human aging, young mice supplemented with TMAO in chow, and in old mice via suppression of gut microbe-dependent production of TMAO with DMB. Importantly, our experiments in isolated arteries incubated acutely with TMAO established the direct effects of TMAO in mediating endothelial dysfunction.

Although an inverse relation between plasma TMAO levels and FMDBA has been reported in patients with stable angina41, to our knowledge, our observations are the first to demonstrate this relation with aging in healthy individuals. Of note, the inverse relation between plasma TMAO levels and FMDBA in our healthy cohort persisted after accounting for multiple traditional cardiovascular risk factors (systolic blood pressure, total and LDL cholesterol, etc.). The present study is also the first to show that TMAO can induce endothelial dysfunction in vivo in healthy young mice, a group typically resistant to adverse stimuli. This finding is consistent with a previous report that TMAO supplementation exacerbates endothelial dysfunction in genetic mouse models of accelerated cellular senescence35. Overall, our results indicate that at least one mechanism by which TMAO stimulates the development of atherosclerosis in mice9,14,42 and is associated with increased CVD risk in humans11–13,42 may be through promoting endothelial dysfunction.

Mechanisms of TMAO-induced endothelial dysfunction with aging: eNOS inactivation and superoxide-related oxidative stress

We next investigated potential mechanisms of reduced NO bioavailability, namely whether TMAO may have affected production of NO by inactivating eNOS and/or scavenging of NO by superoxide-related oxidative stress. First, we found that eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177, an established marker of eNOS activation, was reduced in TMAO-supplemented young mice, and that in old mice treatment with the TMAO-inhibiting compound DMB increased eNOS activation, consistent with a previous report43. These findings suggest that TMAO may reduce NO production, in agreement with observations in cultured endothelial cells incubated with TMAO35,44.

Across our translational models, we consistently observed that TMAO was associated with vascular oxidative stress. First, abundance of nitrotyrosine, an established marker of chronic oxidative stress, was greater in elevated-TMAO conditions in both the aorta of mice and endothelial cells obtained from older adults, and tended to be reduced when we suppressed TMAO production in old mice using DMB. Second, using pharmaco-dissection models in both mice and older adults, we showed that reducing oxidative stress by scavenging excess superoxide restored NO-mediated EDD (endothelial function) to young control levels. This latter observation provides direct evidence that TMAO-induced oxidative stress drives endothelial dysfunction rather than merely being associated with it. Taken together, our findings are the first to demonstrate that TMAO can induce oxidative stress in young and older mice, that a link between higher TMAO and vascular oxidative stress also exists in humans, and that TMAO-associated oxidative stress causes endothelial dysfunction in mice and humans. These observations are consistent with previous reports that TMAO can increase ROS production in cultured endothelial cells35,44,45 and that DMB can reverse oxidative stress in animal models43,46,47.

We also attempted to identify the mechanism by which TMAO induces oxidative stress. TMAO did not alter abundance of the superoxide-generating enzyme NADPH oxidase or p66 Shc1, a marker and master regulator of mitochondrial superoxide production. We also observed no differences in abundance of the SOD antioxidant enzymes, although it is possible that TMAO may suppress SOD activity without affecting total protein abundance, as shown in cultured endothelial cells35,44. The most likely mechanism, however, is the TMAO-induced reduction in eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177. This finding is consistent with greater uncoupling of eNOS, which results in the enzyme producing superoxide instead of NO34 and is a major mechanism for oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction with aging48,49. Finally, TMAO can also induce oxidative stress in cultured endothelial cells via activation of the nod-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome44,45. However, TMAO-induced NLRP3 activation appears to be dependent on inhibition of SOD2 and increased production of mitochondrial ROS45, neither of which were observed here. It is possible that induction of the NLRP3 inflammasome requires high concentrations of TMAO used in cell culture models.

Previous studies have indicated that TMAO induces vascular inflammation33,44,45, likely via activation of NF-κB and/or mitogen-activated protein kinase33, and that DMB supplementation in rats can suppress levels of aortic cytokines in pro-inflammatory conditions43,46,47. Contrary to these previous findings, we observed no obvious effect of TMAO supplementation on aortic pro-inflammatory cytokines or NF-κB. Our findings may be limited by variability and a relatively small sample size; however, we have reported significant differences in aortic inflammatory markers previously with aging and in response to interventions in old mice with comparable sample sizes8,49,50. It is possible that these previous studies reported greater cytokine levels because they used high concentrations of TMAO and/or investigated the effects of TMAO within the context of a pro-inflammatory disease state (e.g., in a model of chronic kidney disease).

In summary, although we observed a consistent effect of TMAO in promoting superoxide-related oxidative stress, we were unable to identify the source of this increased superoxide production, as there were no effects of TMAO on the pathways studied. TMAO may stimulate superoxide production and induces vascular endothelial dysfunction by uncoupling eNOS. Further research will be needed to investigate this potential mechanism.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

The overall findings of these complementary studies provide translational evidence for a key role of the gut microbe-derived metabolite TMAO in mediating age-related vascular endothelial dysfunction via reduced NO bioavailability secondary to superoxide-driven oxidative stress. Our data also provide support for the concept that TMAO-targeted strategies may be effective strategies for preserving vascular endothelial function with aging. Compounds like DMB that target gut microbe-dependent production of TMA may have the most promise as side effects appear minimal, whereas molecules targeting FMO3 and conversion of TMA to TMAO come with unwanted side effects due to TMA accumulation14. Compounds that are non-lethal to the gut microbes are ideal as these should limit off-target effects related to changes in gut microbiome composition. The development of such strategies could have important implications for preserving vascular health with aging, thereby potentially delaying, slowing and/or reducing the development of clinical CVD.

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What is new?

We demonstrate a clear and direct role of higher circulating levels of the gut microbiome-derived metabolite TMAO in age-related vascular endothelial dysfunction in both mice and healthy humans.

Using multiple complementary in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo translational models in both mice and humans, we show that TMAO impairs endothelial function by promoting superoxide-dependent oxidative stress and reducing NO bioavailability.

What is relevant?

Age-related vascular endothelial dysfunction is a major antecedent and key initiating step in the development of CVD, including hypertension.

Emerging evidence suggests that age-related changes in the gut microbiome can influence the cardiovascular system.

This study identifies a novel upstream mechanism, higher circulating levels of TMAO, of age-related vascular endothelial dysfunction that could be targeted to improve vascular health with aging, thereby reducing CVD risk.

Summary

We show that higher circulating levels of TMAO promote age-related endothelial dysfunction by inducing vascular superoxide-dependent oxidative stress and reducing NO bioavailability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to sincerely thank Jill Miyamoto-Ditmon, Danijel Djukovic, Amy Bazzoni, Zachary Condon, Zachary Cook, Christopher J Angiletta and Laura E Griffin for assistance with data collection and analysis.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by NIH grants: R01 HL134887 (D.R.S.); Administrative Supplement HL134887-02S1 (D.R.S. & V.E.B.); and F32 HL140875 (V.E.B.).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST / DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part I: aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107:139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Najjar SS, Scuteri A, Lakatta EG. Arterial aging: is it an immutable cardiovascular risk factor? Hypertension. 2005;46:454–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cahill PA, Redmond EM. Vascular endothelium - Gatekeeper of vessel health. Atherosclerosis. 2016;248:97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajendran P, Rengarajan T, Thangavel J, Nishigaki Y, Sakthisekaran D, Sethi G, Nishigaki I. The vascular endothelium and human diseases. Int J Biol Sci. 2013;9:1057–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seals DR, Kaplon RE, Gioscia-Ryan RA, LaRocca TJ. You’re only as old as your arteries: translational strategies for preserving vascular endothelial function with aging. Physiology (Bethesda). 2014;29:250–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Loo B, Labugger R, Skepper JN, Bachschmid M, Kilo J, Powell JM, Palacios-Callender M, Erusalimsky JD, Quaschning T, Malinski T, Gygi D, Ullrich V, Lüscher TF. Enhanced peroxynitrite formation is associated with vascular aging. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1731–1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachschmid MM, Schildknecht S, Matsui R, Zee R, Haeussler D, Cohen RA, Pimental D, Loo BVD. Vascular aging: chronic oxidative stress and impairment of redox signaling-consequences for vascular homeostasis and disease. Ann Med. 2013;45:17–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunt VE, Gioscia-Ryan RA, Richey JJ, Zigler MC, Cuevas LM, González A, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Battson ML, Smithson AT, Gilley AD, Ackermann G, Neilson AP, Weir T, Davy KP, Knight R, Seals DR. Suppression of the gut microbiome ameliorates age-related arterial dysfunction and oxidative stress in mice. J Physiol. 2019;597:2361–2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, Feldstein AE, Britt EB, Fu X, Chung Y- M, Wu Y, Schauer P, Smith JD, Allayee H, Tang WHW, DiDonato JA, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472:57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romano KA, Vivas EI, Amador-Noguez D, Rey FE. Intestinal microbiota composition modulates choline bioavailability from diet and accumulation of the proatherogenic metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide. mBio. 2015;6:e02481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senthong V, Wang Z, Li XS, Fan Y, Wu Y, Tang WHW, Hazen SL. Intestinal Microbiota-Generated Metabolite Trimethylamine-N-Oxide and 5-Year Mortality Risk in Stable Coronary Artery Disease: The Contributory Role of Intestinal Microbiota in a COURAGE-Like Patient Cohort. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu W, Gregory JC, Org E, Buffa JA, Gupta N, Wang Z, Li L, Fu X, Wu Y, Mehrabian M, Sartor RB, McIntyre TM, Silverstein RL, Tang WHW, DiDonato JA, Brown JM, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Gut Microbial Metabolite TMAO Enhances Platelet Hyperreactivity and Thrombosis Risk. Cell. 2016;165:111–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanitsoraphan C, Rattanawong P, Charoensri S, Senthong V. Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. Curr Nutr Rep. 2018;15:73–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Z, Roberts AB, Buffa JA, Levison BS, Zhu W, Org E, Gu X, Huang Y, Zamanian-Daryoush M, Culley MK, DiDonato AJ, Fu X, Hazen JE, Krajcik D, DiDonato JA, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Non-lethal Inhibition of Gut Microbial Trimethylamine Production for the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Cell. 2015;163:1585–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang WHW, Wang Z, Levison BS, Koeth RA, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1575–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang WHW, Wang Z, Kennedy DJ, Wu Y, Buffa JA, Agatisa-Boyle B, Li XS, Levison BS, Hazen SL. Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) pathway contributes to both development of renal insufficiency and mortality risk in chronic kidney disease. Circ Res. 2015;116:448–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang WHW, Wang Z, Li XS, Fan Y, Li DS, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Increased Trimethylamine N-Oxide Portends High Mortality Risk Independent of Glycemic Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Clin Chem. 2017;63:297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu R, Wang Q. Towards understandingbrain-gut-microbiome connections inAlzheimer’s disease. BMC Systems Biology. 2016;:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierce GL, Lesniewski LA, Lawson BR, Beske SD, Seals DR. Nuclear factor-{kappa}B activation contributes to vascular endothelial dysfunction via oxidative stress in overweight/obese middle-aged and older humans. Circulation. 2009;119:1284–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos-Parker JR, Strahler TR, Bassett CJ, Bispham NZ, Chonchol MB, Seals DR. Curcumin supplementation improves vascular endothelial function in healthy middle-aged and older adults by increasing nitric oxide bioavailability and reducing oxidative stress. Aging (Albany NY). 2017;9:187–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossman MJ, Santos-Parker JR, Steward CAC, Bispham NZ, Cuevas LM, Rosenberg HL, Woodward KA, Chonchol M, Gioscia-Ryan RA, Murphy MP, Seals DR. Chronic Supplementation With a Mitochondrial Antioxidant (MitoQ) Improves Vascular Function in Healthy Older Adults. Hypertension. 2018;71:1056–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeVan AE, Johnson LC, Brooks FA, Evans TD, Justice JN, Cruickshank-Quinn C, Reisdorph N, Bryan NS, McQueen MB, Santos-Parker JR, Chonchol MB, Bassett CJ, Sindler AL, Giordano T, Seals DR. Effects of sodium nitrite supplementation on vascular function and related small metabolite signatures in middle-aged and older adults. J Appl Physiol. 2016;120:416–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martens CR, Denman BA, Mazzo MR, Armstrong ML, Reisdorph N, McQueen MB, Chonchol M, Seals DR. Chronic nicotinamide riboside supplementation is well-tolerated and elevates NAD+ in healthy middle-aged and older adults. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Z, Levison BS, Hazen JE, Donahue L, Li X-M, Hazen SL. Measurement of trimethylamine-N-oxide by stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2014;455:35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boutagy NE, Neilson AP, Osterberg KL, Smithson AT, Englund TR, Davy BM, Hulver MW, Davy KP. Probiotic supplementation and trimethylamine-N-oxide production following a high-fat diet. Obesity. 2015;23:2357–2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boutagy NE, Neilson AP, Osterberg KL, Smithson AT, Englund TR, Davy BM, Hulver MW, Davy KP. Short-term high-fat diet increases postprandial trimethylamine-N-oxide in humans. Nutr Res. 2015;35:858–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thijssen DHJ, Bruno RM, van Mil ACCM, Holder SM, Faita F, Greyling A, Zock PL, Taddei S, Deanfield JE, Luscher T, Green DJ, Ghiadoni L. Expert consensus and evidence-based recommendations for the assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:2534–2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eskurza I, Monahan KD, Robinson JA, Seals DR. Effect of acute and chronic ascorbic acid on flow-mediated dilatation with sedentary and physically active human ageing. J Physiol. 2004;556:315–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colombo PC, Ashton AW, Celaj S, Talreja A, Banchs JE, Dubois NB, Marinaccio M, Malla S, Lachmann J, Ware JA, Le Jemtel TH. Biopsy coupled to quantitative immunofluorescence: a new method to study the human vascular endothelium. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:1331–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eskurza I, Kahn ZD, Seals DR. Xanthine oxidase does not contribute to impaired peripheral conduit artery endothelium-dependent dilatation with ageing. J Physiol. 2006;571:661–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rippe C, Lesniewski L, Connell M, LaRocca T, Donato A, Seals D. Short-term calorie restriction reverses vascular endothelial dysfunction in old mice by increasing nitric oxide and reducing oxidative stress. Aging Cell. 2010;9:304–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gioscia-Ryan RA, LaRocca TJ, Sindler AL, Zigler MC, Murphy MP, Seals DR. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant (MitoQ) ameliorates age-related arterial endothelial dysfunction in mice. J Physiol. 2014;592:2549–2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seldin MM, Meng Y, Qi H, Zhu W, Wang Z, Hazen SL, Lusis AJ, Shih DM. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Promotes Vascular Inflammation Through Signaling of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and Nuclear Factor-κB. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seals DR, Jablonski KL, Donato AJ. Aging and vascular endothelial function in humans. Clin Sci. 2011;120:357–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ke Y, Li D, Zhao M, Liu C, Liu J, Zeng A, Shi X, Cheng S, Pan B, Zheng L, Hong H. Gut flora-dependent metabolite Trimethylamine-N-oxide accelerates endothelial cell senescence and vascular aging through oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;116:88–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Claesson MJ, Cusack S, O’Sullivan O, Greene-Diniz R, de Weerd H, Flannery E, Marchesi JR, Falush D, Dinan T, Fitzgerald G, Stanton C, van Sinderen D, O’Connor M, Harnedy N, O’Connor K, Henry C, O’Mahony D, Fitzgerald AP, Shanahan F, Twomey C, Hill C, Ross RP, O’Toole PW. Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108 Suppl 1:4586–4591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hébuterne X. Gut changes attributed to ageing: effects on intestinal microflora. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2003;6:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Craciun S, Balskus EP. Microbial conversion of choline to trimethylamine requires a glycyl radical enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:21307–21312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeboah J, Crouse JR, Hsu F-C, Burke GL, Herrington DM. Brachial flow-mediated dilation predicts incident cardiovascular events in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 2007;115:2390–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shechter M, Issachar A, Marai I, Koren-Morag N, Freinark D, Shahar Y, Shechter A, Feinberg MS. Long-term association of brachial artery flow-mediated vasodilation and cardiovascular events in middle-aged subjects with no apparent heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2009;134:52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chou R-H, Chen C-Y, Chen I-C, Huang H-L, Lu Y-W, Kuo C-S, Chang C-C, Huang P-H, Chen J-W, Lin S-J. Trimethylamine N-Oxide, Circulating Endothelial Progenitor Cells, and Endothelial Function in Patients with Stable Angina. Sci Rep. 2019;:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Li L, Smith JD, DiDonato JA, Chen J, Li H, Wu GD, Lewis JD, Warrier M, Brown JM, Krauss RM, Tang WHW, Bushman FD, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:576–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li T, Chen Y, Gua C, Li X. Elevated Circulating Trimethylamine N-Oxide Levels Contribute to Endothelial Dysfunction in Aged Rats through Vascular Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Front Physiol. 2017;8:350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun X, Jiao X, Ma Y, Liu Y, Zhang L, He Y, Chen Y. Trimethylamine N-oxide induces inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in human umbilical vein endothelial cells via activating ROS-TXNIP-NLRP3 inflammasome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;481:63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen M-L, Zhu X-H, Ran L, Lang H-D, Yi L, Mi M-T. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Induces Vascular Inflammation by Activating the NLRP3 Inflammasome Through the SIRT3-SOD2-mtROS Signaling Pathway. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li T, Gua C, Wu B, Chen Y. Increased circulating trimethylamine N-oxide contributes to endothelial dysfunction in a rat model of chronic kidney disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;495:2071–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen H, Li J, Li N, Liu H, Tang J. Increased circulating trimethylamine N-oxide plays a contributory role in the development of endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in the RUPP rat model of preeclampsia. Hypertension in Pregnancy. 2019;38:96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Y-M, Huang A, Kaley G, Sun D. eNOS uncoupling and endothelial dysfunction in aged vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1829–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sindler AL, Fleenor BS, Calvert JW, Marshall KD, Zigler ML, Lefer DJ, Seals DR. Nitrite supplementation reverses vascular endothelial dysfunction and large elastic artery stiffness with aging. Aging Cell. 2011;10:429–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gioscia-Ryan RA, Battson ML, Cuevas LM, Eng JS, Murphy MP, Seals DR. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant therapy with MitoQ ameliorates aortic stiffening in old mice. J Appl Physiol. 2018;124:1194–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.