Abstract

Zwitterionic surface modification is a promising strategy for nanomedicines to achieve prolonged circulation time and thus effective tumor accumulation. However, zwitterion modified nanoparticles suffer from reduced cellular internalization efficiency.

Methods: A polyprodrug-based nanomedicine with zwitterionic-to-cationic charge conversion ability (denoted as ZTC-NMs) was developed for enhanced chemotherapeutic drug delivery. The polyprodrug consists of pH-responsive poly(carboxybetaine)-like zwitterionic segment and glutathione-responsive camptothecin prodrug segment.

Results: The ZTC-NMs combine the advantages of zwitterionic surface and polyprodrug. Compared with conventional zwitterionic surface, the ZTC-NMs can respond to tumor microenvironment and realize ZTC surface charge conversion, thus improve cellular internalization efficiency of the nanomedicines.

Conclusions: This ZTC method offers a strategy to promote the drug delivery efficiency and therapeutic efficacy, which is promising for the development of cancer nanomedicines.

Keywords: charge conversion, zwitterionic, polyprodrug, triggered drug release, nanomedicine

Introduction

Chemotherapy, which exploits small molecule antitumor drugs, is an indispensable approach in the clinic. In recent years, a wide range of chemotherapeutic drugs with high anticancer activities, such as doxorubicin, camptothecin (CPT) and paclitaxel, have been developed for chemotherapy 1-4. Unfortunately, most of these drugs suffer from nonspecific biodistribution, which may cause poor bioavailability and severe side effects. Nanomedicines offer an opportunity to address the mentioned limitations due to their potential of achieving improved drug delivery through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect 5-13. Polyprodrug strategy, which conjugates drugs to the polymer chains through responsive linkers, has been reported for the development of nanomedicine-based drug delivery systems 14-21. Compared to conventional drug carriers using physical loading approach, polyprodrug strategy shows distinct advantages such as high drug loading content, high loading stability and controlled drug release 22-28. Thus, polyprodrug-based nanomedicine is a promising approach for the delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs.

The surface modification is a very important factor for nanomedicines to achieve satisfactory in vivo performance. Neutral “stealth” coating is often favored for surface modification because it can prolong circulation time of nanomedicines and thus realize effective tumor accumulation 29-34. Particularly, zwitterionic structures, such as sulfobetaine and carboxybetaine, have recently received considerable attention as non-interacting surfaces that can reduce nonspecific adsorption 35, 36. Nanoparticles with zwitterionic surfaces exhibit high colloidal stability, long blood circulation time and high biocompatibility, resulting in effective tumor accumulation through the EPR effect 37-41. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that zwitterionic poly(carboxybetaine) (PCB) modification can overcome the barriers associated with the use of polyethylene glycol (PEG) by avoiding the accelerated blood clearance phenomenon 42, 43. In order to achieve optimal treatment effect, nanomedicines are expected to effectively enter cancer cells once they reach tumor tissue. Unfortunately, compared to positively charged nanoparticles, zwitterionic nanoparticles suffer from reduced cellular internalization efficiency due to the poor zwitterionic surface-cell interactions 44, 45. In recent years, stimuli-responsive charge conversion strategy has been reported to promote the cellular internalization efficiency of nanomedicines 46-49. Under certain stimulus, the nanomedicines can achieve surface charge conversion from neutral or negative to positive, resulting in improved nanomedicine-cell interaction. However, the combining of polyprodrug nanomedicine and stimuli-responsive PCB-like modification with zwitterionic-to-cationic (ZTC) charge conversion ability to realize enhanced drug delivery has not yet been reported to the best of our knowledge.

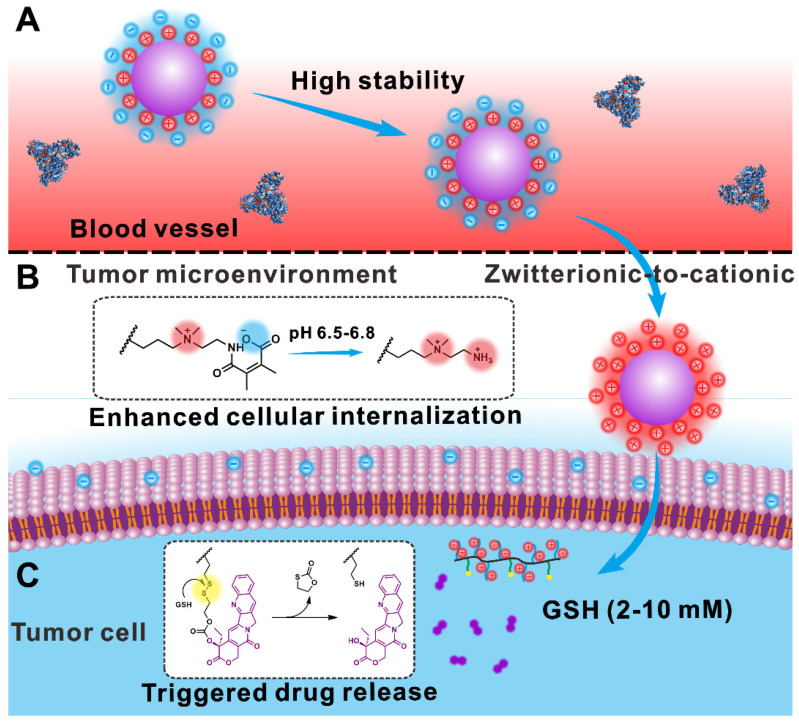

Herein, we report a pH-responsive PCB-like zwitterion-modified nanomedicine with ZTC charge conversion ability (denoted as ZTC-NM) for chemotherapeutic drug delivery. A polyprodrug that is composed of pH-responsive PCB-like zwitterionic segment and glutathione (GSH)-responsive poly-CPT segment was synthesized. The PCB-like zwitterionic structure consists of positively charged quaternary ammonium salt and negatively charged carboxyl group formed by the reaction of amino group and 2,3-dimethylmaleic anhydride (DMMA). Then the ZTC-NMs, which combined the advantages of polyprodrug and PCB-like modification, were prepared by self-assembly of the polyprodrug. As shown in Figure 1A, due to nanosized diameter and PCB-like zwitterionic surface modification, the ZTC-NMs can realize prolonged blood circulation time, which will facilitate tumor accumulation through the EPR effect. In tumor microenvironment, the amide bond formed between DMMA and amino group will respond to tumor pH (6.5-6.8) and achieve acid-responsive cleavage, leading to ZTC surface charge conversion of the ZTC-NMs 50. Due to the presence of highly positive quaternary ammonium salt, the resulting strong cationic NMs can rapidly enter tumor cells through effective electrostatic interaction with negatively charged cell membrane. Therefore, the ZTC charge conversion property can improve the cellular internalization efficiency of NMs and thus promote the drug delivery efficiency (Figure 1B). Moreover, after being taken up by tumor cells, the disulfide bonds in ZTC-NMs will be rapidly cleaved in the presence of intracellular GSH (Figure 1C), which would achieve triggered CPT release through a cascade reaction 51, 52.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration showing the drug delivery process of ZTC-NMs. (A) The PCB-like zwitterion-modified nanomedicine shows high stability in blood circulation, resulting in efficient tumor accumulation through the EPR effect. (B) In tumor acidic microenvironment, the acid-induced zwitterionic-to-cationic surface charge conversion leads to enhanced cellular internalization of the nanomedicine. (C) The high level of intracellular GSH permits triggered drug release.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and characterization of polyprodrug

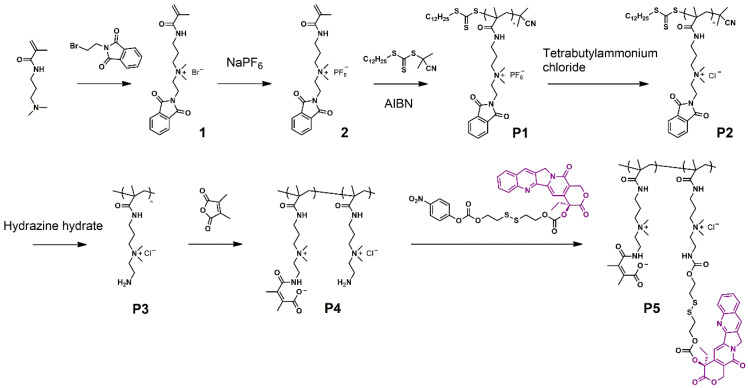

The dual-responsive polyprodrug (P5) was synthesized as shown in Scheme 1 and Scheme S1-S4. At first, a quaternary ammonium salt monomer (1) was synthesized by the reaction between N-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]methacrylamide and N-(2-bromoethyl)phthalimide. Then the hexafluorophosphate salt monomer (2) was prepared for polymerization. Through reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization, the quaternary ammonium salt polymer (P1) was synthesized. Afterwards, the P1 was reacted with tetrabutylammonium chloride for ion exchange, obtaining P2. According to the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) results, the degree of polymerization and molecular weight of P2 were determined to be 32 and 12.2 kDa, respectively (Figure S7). The synthesized P2 was further treated with hydrazine hydrate to remove the protecting groups, yielding water-soluable polymer P3. Then DMMA was conjugated to the amino groups of P3 to prepare the polymer with zwitterionic structure (P4). The P5 was finally obtained by conjugating CPT to the zwitterionic polymer P4 through GSH-responsive disulfide linker. To serve as a control group, a polyprodrug without pH-responsiveness (P7) was synthesized by the similar method, except that DMMA was replaced with succinic anhydride (Scheme S5). NMR, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and UV-vis absorbance characterizations demonstrated the successful synthesis of monomers and polymers (Figure S1-S11). As calculated from the results of NMR spectra, approximately 75% of P4 and P6 were successfully linked with DMMA and succinic anhydride (Figure S9 and S10). By measuring the absorbance at 370 nm, the CPT loading contents of P5 and P7 were determined to be 14.9% and 16.5%, respectively (Figure S11).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis process of the polyprodrug.

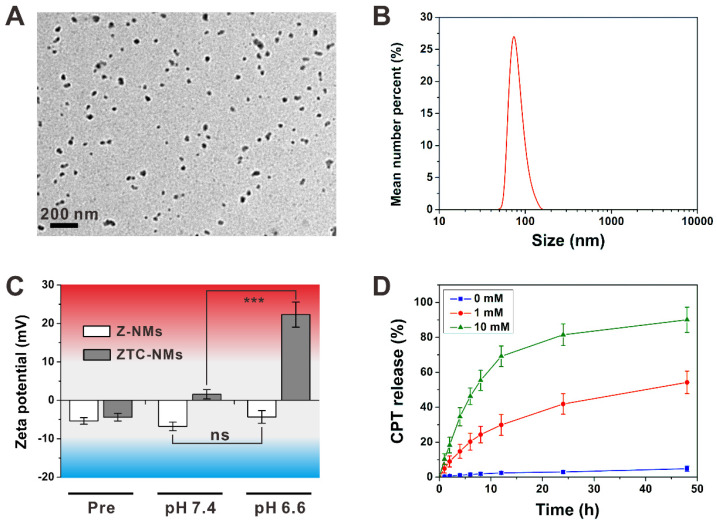

Preparation and characterization of the polyprodrug-based nanomedicine

The amphiphilic polyprodrugs, P5 and P7, can self-assemble into nanoparticles (ZTC-NMs and Z-NMs) with diameters of about 50 nm (Figure 2A and Figure S12). As shown in Figure 2B and Figure S13-S14, ZTC-NMs and Z-NMs showed similar hydrodynamic diameters and colloidal stabilities, which were characterized by dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements. These results demonstrated that the prepared ZTC-NMs and Z-NMs were suitable for in vivo application. Then the pH-responsive property of the ZTC-NMs was determined by DLS. As shown in Figure 2C, both ZTC-NMs and Z-NMs showed neutral surface charges (between -10 mV and 10 mV) due to the zwitterionic surface modifications. After 3 h of incubation at pH 7.4, the ZTC-NMs still showed neutral surface charges. However, the surface charge of ZTC-NMs was converted into strong cationic (> 20 mV) after incubation at pH 6.6 for 3 h, which was due to the pH-induced detachment of DMMA groups and the presence of highly positive quaternary ammonium salt. In general, the nanomedicines that accumulate in tumor tissue through EPR effect can retain for a long time (more than 24 h); therefore, the ZTC-NMs that can achieve ZTC charge conversion within 3 h are suitable for tumor microenvironment-responsive drug delivery. In contrast, after incubation at different pH, the Z-NMs didn't show obvious change in surface charge due to the non-responsiveness of zwitterionic structure in Z-NMs. The size changes of ZTC-NMs in different conditions were also determined. As shown in Figure S15, the size of the ZTC-NMs didn't show obvious change at both pH 7.4 and pH 6.6. Then the GSH-responsive drug release behavior of the ZTC-NMs was investigated by dialysis method. In the absence of GSH, the ZTC-NMs didn't show obvious drug leakage (Figure 2D). Considering the low GSH concentration in body fluids and in the extracellular milieu, the relatively high stability of the nanomedicines led to minimal side effects. This is one of the important advantages of polyprodrug-based nanomedicines when compared with nanomedicines that based on physical encapsulation approach. However, when incubated with 1 × 10-3 M GSH, accelerated drug release was observed, with more than 50% CPT released in 48 h. The drug release rate was further increased when the ZTC-NMs were incubated with higher concentration GSH (1 × 10-2 M). To investigate the release mechanism of the ZTC-NMs in the presence of GSH, the release medium was analyzed by LC-MS. A peak at m/z 349.1 (calculated as 349.1) was found in the spectrum (Figure S16), indicating that free CPT was released. These results demonstrated that the GSH can trigger free CPT release by cleavage of disulfide bonds and subsequent cascade reaction 51-54. It has been demonstrated that the GSH concentration inside cancer cells is relatively high; therefore, the ZTC-NMs would rapidly release CPT inside cancer cells.

Figure 2.

(A) Transmission electron microscope (TEM) image of ZTC-NMs. (B) Effective particle diameter of ZTC-NMs. (C) Zeta potential results of Z-NMs and ZTC-NMs after incubation at pH 7.4 and 6.6 for 3 h (n = 3, ***P < 0.001). (D) In vitro CPT release profiles of ZTC-NMs in the presence or absence of GSH (n = 3).

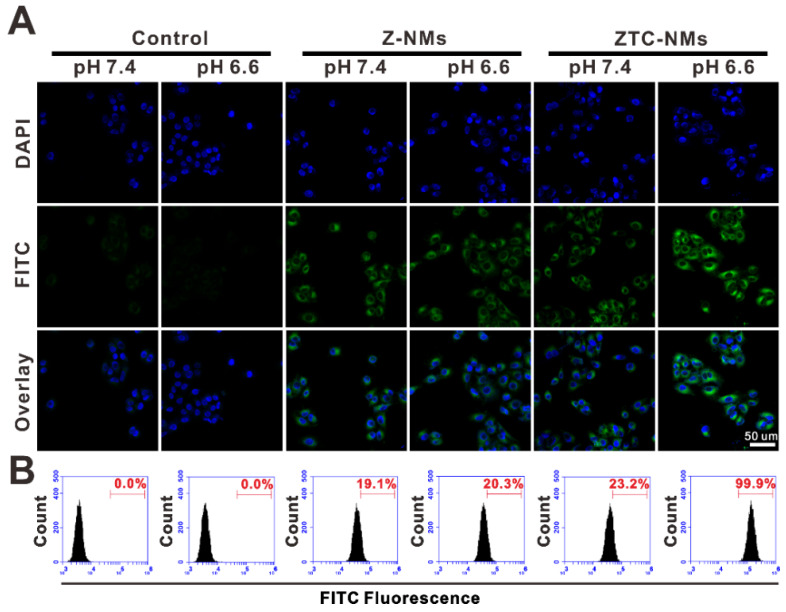

In vitro cellular study

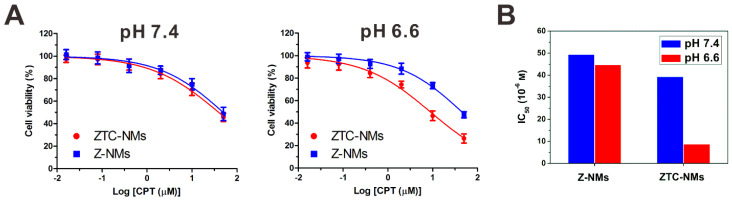

The enhanced cellular internalization of the ZTC-NMs was evaluated on A549 cells. To observe the cellular uptake of nanomedicines, both ZTC-NMs and Z-NMs were labeled by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). The FITC-labeled NMs were pretreated with pH 7.4 or 6.6 buffer solution for 3 h. Then A549 cells were incubated with pretreated ZTC-NMs or Z-NMs for 2 h. Thereafter, cells were stained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and analyzed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and flow cytometry (FCM). As shown in Figure 3A and 3B, cells with pH 7.4 pretreated ZTC-NMs incubation showed relatively weak fluorescence. The low cellular uptake may be attributed to the zwitterionic surface of the ZTC-NMs. However, obviously stronger green fluorescence was found inside the cells when incubated with pH 6.6 pretreated ZTC-NMs, indicating enhanced cellular internalization of the ZTC-NMs. In contrast, both pH 7.4 and pH 6.6 pretreated Z-NMs showed low cellular uptake, indicating non-responsiveness of the Z-NMs. These results confirmed that the pH-responsive ZTC charge conversion ability of the ZTC-NMs could enhance intracellular drug delivery in weak acidic environment. Then the cell growth inhibition efficacies of ZTC-NMs and Z-NMs were further evaluated. Cells were incubated with pH 7.4 and pH 6.6 pretreated NMs for 6 h and then with fresh culture medium for additional 42 h. Next, a methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay was conducted to measure the cell viabilities. As shown in Figure 4A, the pH 7.4 pretreated ZTC-NMs and Z-NMs showed comparable cell growth inhibition ability; however, compared to Z-NMs, the pH 6.6 pretreated ZTC-NMs showed much improved cytotoxicity. The calculated IC50 value of pH 6.6 pretreated ZTC-NMs was 5.1-fold lower than that of pH 6.6 pretreated Z-NMs (Figure 4B). This pH-induced high anticancer efficacy can be a result of ZTC charge conversion-enhanced intracellular drug delivery.

Figure 3.

(A) Confocal fluorescence images and (B) flow cytometry (FCM) analysis of A549 cells upon incubation with different pH pretreated FITC-labeled Z-NMs and ZTC-NMs for 2 h.

Figure 4.

(A) Viability of A549 cells incubated with ZTC-NMs and Z-NMs at different pH for 6 h and then incubated with fresh culture medium for another 42 h. (n = 5/group) (B) The IC50 values of Z-NMs and ZTC-NMs at different pH (based on data in (A)).

In vivo positron emission tomography (PET) imaging

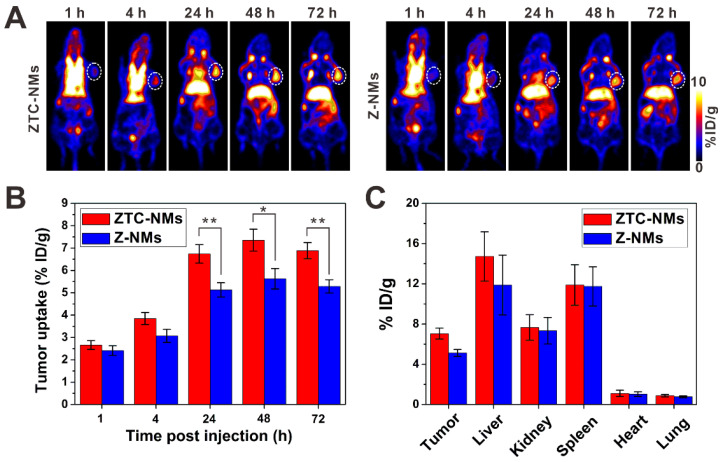

Next, the in vivo performance of ZTC-NMs was studied by PET imaging. Zirconium-89 (89Zr) was used for radiolabeling. The 89Zr-Z-NMs and 89Zr-ZTC-NMs were injected intravenously into A549 tumor-bearing mice for PET image acquisition at 1, 4, 24, 48 and 72 h postinjection. Quantitative analysis in heart (with blood) region demonstrated long blood circulation times of the ZTC-NMs and Z-NMs (Figure S17). The acquired PET images at different time points indicated that both ZTC-NMs and Z-NMs effectively accumulated in the tumor region, probably due to the EPR effect of nanomedicines (Figure 5A). The long retention time facilitates the effective response of the ZTC-NMs to tumor microenvironment stimulation and realize ZTC charge conversion. Compared with Z-NMs, ZTC-NMs showed obviously higher tumor accumulation and retention at 24, 48 and 72 h postinjection (Figure 5B). Considering the similar size and surface property of ZTC-NMs and Z-NMs, the enhanced tumor accumulation and retention of ZTC-NMs can be a result of high cell-nanomedicine interaction, resulting from tumor microenvironment-induced ZTC charge conversion. At 72 h postinjection, ex vivo biodistribution study was performed by quantifying radioactivity in the tumor and different organs using a γ-counter (Figure 5C). The result was consistent with quantitative PET region-of-interest analysis, indicating enhanced drug delivery ability of the ZTC-NMs.

Figure 5.

(A) PET images of A549 tumor-bearing mice after intravenous injection of 89Zr-Z-NMs or 89Zr-ZTC-NMs. The white circles indicate the tumor area. (B) Tumor uptake efficiencies of the 89Zr-Z-NMs or 89Zr-ZTC-NMs at different time points. (C) Biodistribution of tumor and primary organs at 72 h postinjection. (n = 3/group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

In vivo antitumor study

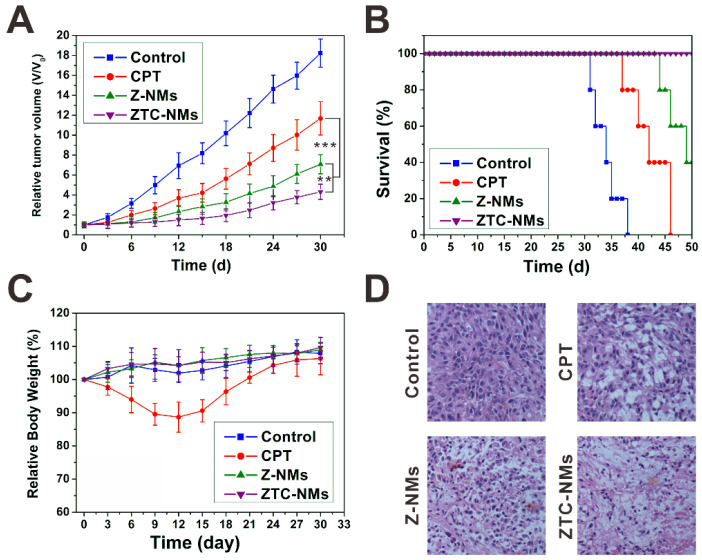

Encouraged by the effective tumor targeting behavior, the in vivo antitumor effect of ZTC-NMs was further evaluated on A549 tumor mice. Free CPT was used as a control. Saline or different formulations were intravenously injected into tumor-bearing mice every 3 days for 5 times (CPT equivalent dose: 3 mg kg-1). As shown in Figure 6A, both free CPT and nanomedicine treatments delayed tumor growth. The free CPT displayed only moderate antitumor effect; however, the NMs showed more effective tumor inhibition, which could be attributed to the tumor targeted drug delivery. Importantly, compared with Z-NMs, the ZTC-NMs showed the most potent antitumor effect (Figure 6D and Figure S18). As a result, the survival time of ZTC-NM-treated mice was greatly prolonged (Figure 6B). This result demonstrated that the ZTC charge conversion ability was conducive to enhance drug delivery. Meanwhile, during the treatment period, the mice treated with ZTC-NMs and Z-NMs didn't show obvious body weight loss or organ damages; however, free CPT-treated mice suffered from systemic toxicity induced weight loss (Figure 6C and Figure S19). These results indicated that the NMs reduced side effects caused by anticancer drug.

Figure 6.

(A) Tumor growth curves of the A549 tumor-bearing mice treated with different formulas. (B) Survival curves of the mice treated with different samples. (C) Mouse body-weight changes during the treatments. (D) H&E analyses of tumor tissues after different treatments. (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Conclusions

In summary, a nanomedicine with zwitterionic-to-cationic surface charge conversion ability was developed for enhanced delivery of chemotherapeutic drug. The nanomedicine was prepared by self-assembly of amphiphilic polymer which contains pH-responsive PCB-like zwitterionic segment and GSH-responsive prodrug segment. Owing to the zwitterionic surface modification, the nanomedicine exhibited high stability and prolonged circulation time. Furthermore, the ZTC charge conversion ability of the nanomedicine in tumor microenvironment promoted cell internalization, which resulted in enhanced tumor accumulation and retention. In tumor cells, controlled drug release was achieved through GSH-triggered cleavage of disulfide bonds. Considering the effective tumor inhibition and low systemic toxicity in vivo, the ZTC-NMs have the potential for anticancer drug delivery.

Methods

Preparation and characterizations of nanomedicines

Briefly, P5 (1 mg) was dissolved in 500 μL of DMSO and then added into 4 mL of distilled water dropwise under stirring. The organic solvents were removed through ultrafiltration, obtaining ZTC-NMs. The Z-NMs were prepared under the same experimental conditions except that the P5 was replaced with P7. The morphologies, effective particle diameters and Zeta potentials of the samples were studied by Tecnai TF30 TEM (FEI, Hillsboro) and SZ-100 nanoparticle analyzer (HORIBA Scientific). UV-vis absorption spectra of the samples were measured by Genesys 10S UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific).

In vitro drug release

The in vitro GSH-triggered CPT release behaviors of the samples were evaluated by using a dialysis method. The ZTC-NMs were dispersed in 2 mL of media (phosphate buffered saline, 1 mM GSH or 10 mM GSH) and added to dialysis bags (MWCO: 3500 Da). Then the dialysis bags were placed in 20 mL of environmental media (n = 3) and incubated at 37 °C. At appropriate time points, 2 mL of the environmental medium was taken out for quantification of released CPT by high performance liquid chromatography at the wavelength of 370 nm. And same amount of fresh medium was added. To verify that the free CPT molecules were released by cleavage of disulfide bonds and subsequent cascade reaction, the release medium was analyzed by using LC-MS.

In vitro cell experiments

The in vitro cellular uptake study and antitumor activity study were assessed on A549 cell line, which was purchased from American type culture collection (ATCC). To investigate the cellular uptake of ZTC-NMs and Z-NMs, A549 cells were seeded into 8-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Then, pretreated (at pH 7.4 or 6.6 for 3 h) FITC-labeled NMs were added to wells and incubated for 2 h. Then the culture media were removed, and the cells were fixed with Z-Fix solution and stained with DAPI. Then the cellular uptake was determined by confocal images and flow cytometry analyses. For in vitro cell experiments, A549 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 3 × 103 cells per well and incubated with different formulas at different pH for 6 h to allow ZTC charge conversion and cellular internalization (n = 5/group). Then the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium and the cells were incubated for another 42 h. Thereafter, the relative cell viabilities were measured by MTT assay. The IC50 values were calculated by using GraphPad Prism 5.

In vivo PET imaging

All animal experiments were performed under a National Institutes of Health Animal Care and Use Committee (NIHACUC) approved protocol. Athymic nude mice (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were subcutaneously implanted with 3 × 106 A549 cells. Deferoxamine (DFO) conjugated polyprodrug was synthesized for 89Zr labeling (Scheme S6) 24, 55. The 89Zr-ZTC-NMs or 89Zr-Z-NMs solution (100 μL, 200 μCi) was intravenously injected into A549 tumor-bearing mice (n = 3/group). At appropriate time points after injection, PET images were acquired by using an Inveon small-animal PET scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). At 72 h post-injection, the mice were sacrificed for biodistribution study. Tumors and major organs were collected and assayed for radioactivity using a gamma counter. The percent injected dose/gram of tissue (%ID/g) was then calculated.

In vivo therapy

A549 tumor-bearing mice were randomly divided into 4 groups (n = 6/group): control group, free CPT group, ZTC-NMs group and Z-NMs group. When the tumors reached 80 mm3, the mice were treated with different formulas (3 mg CPT kg-1 equivalent) via intravenous injection every 3 days for 5 times. Tumor volume and body weight were monitored every 3 days. Tumor volume was calculated as (major axis) × (minor axis)2/2. Based on the Animal Study Protocol, mice with oversized tumor (major axis > 20 mm) or significant weight loss (> 20%) were euthanized. After treatment, one mouse from each group was euthanized, major organs and tumors were collected for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining 56.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81971621, No. 81671707), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2019A1515012212, No. 2018A030313678), Research Fund for Lin He's Academician Workstation of New Medicine and Clinical Translation, the Intramural Research Program (IRP) of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Abbreviations

- CPT

camptothecin

- EPR

enhanced permeability and retention

- PCB

poly(carboxybetaine)

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- ZTC

zwitterionic-to-cationic

- NM

nanomedicine

- GSH

glutathione

- DMMA

2,3-dimethylmaleic anhydride

- RAFT

reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- TEM

transmission electron microscope

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- DAPI

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- CLSM

confocal laser scanning microscopy

- FCM

flow cytometry

- MTT

methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium

- PET

positron emission tomography

- 89Zr

Zirconium-89

- DFO

deferoxamine

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

References

- 1.Bailly C. Contemporary challenges in the design of topoisomerase II inhibitors for cancer chemotherapy. Chem Rev. 2012;112:3611–40. doi: 10.1021/cr200325f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang F, Zhu G, Jacobson O, Liu Y, Chen K, Yu G. et al. Transformative nanomedicine of an amphiphilic camptothecin prodrug for long circulation and high tumor uptake in cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2017;11:8838–48. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b03003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petros RA, DeSimone JM. Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2010;9:615–27. doi: 10.1038/nrd2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu GC, Yang Z, Fu X, Yung BC, Yang J, Mao ZW. et al. Polyrotaxane-based supramolecular theranostics. Nat Commun. 2018;9:766. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03119-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu Y, Aimetti AA, Langer R, Gu Z. Bioresponsive materials. Nat Rev Mater. 2016;2:16075. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang S, Zhou Z, Wang Z, Liu Y, Jacobson O, Shen Z. et al. Gadolinium metallofullerene-based activatable contrast agent for tumor signal amplification and monitoring of drug release. Small. 2019;15:1900691. doi: 10.1002/smll.201900691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mura S, Nicolas J, Couvreur P. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery. Nat Mater. 2013;12:991–1003. doi: 10.1038/nmat3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamaly N, Yameen B, Wu J, Farokhzad OC. Degradable controlled-release polymers and polymeric nanoparticles: mechanisms of controlling drug release. Chem Rev. 2016;116:2602–63. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang S, Lin J, Wang Z, Zhou Z, Bai R, Lu N. et al. Core-satellite polydopamine-gadolinium metallofullerene nanotheranostics for multimodal imaging guided combination cancer therapy. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1701013. doi: 10.1002/adma.201701013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin L-S, Huang T, Song J, Ou X-Y, Wang Z, Deng H. et al. Synthesis of copper peroxide nanodots for H2O2 self-supplying chemodynamic therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:9937–45. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b03457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park J, Choi Y, Chang H, Um W, Ryu JH, Kwon IC. Alliance with EPR effect: combined strategies to improve the EPR effect in the tumor microenvironment. Theranostics. 2019;9:8073–90. doi: 10.7150/thno.37198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin LS, Wang JF, Song JB, Liu YJ, Zhu GZ, Dai YL. et al. Cooperation of endogenous and exogenous reactive oxygen species induced by zinc peroxide nanoparticles to enhance oxidative stress-based cancer therapy. Theranostics. 2019;9:7200–9. doi: 10.7150/thno.39831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng H, Fan GL, Fan JH, Yuan P, Deng FA, Qiu XZ. et al. Epigenetics-inspired photosensitizer modification for plasma membrane-targeted photodynamic tumor therapy. Biomaterials. 2019;224:119497. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Q, Shao S, Wang J, Xu C, Xiang J, Piao Y. et al. Enzyme-activatable polymer-drug conjugate augments tumour penetration and treatment efficacy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019;14:799–809. doi: 10.1038/s41565-019-0485-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheetham AG, Chakroun RW, Ma W, Cui H. Self-assembling prodrugs. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46:6638–63. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00521k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo YY, Zhang J, Ding F, Pan GF, Li J, Feng J. et al. Stressing the role of DNA as a drug carrier: synthesis of DNA-drug conjugates through grafting chemotherapeutics onto phosphorothioate oligonucleotides. Adv Mater. 2019;31:1807533. doi: 10.1002/adma.201807533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S, Wang Z, Yu G, Zhou Z, Jacobson O, Liu Y. et al. Tumor-specific drug release and reactive oxygen species generation for cancer chemo/chemodynamic combination therapy. Adv Sci. 2019;6:1801986. doi: 10.1002/advs.201801986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Ji W, Lu Z, Liu L, Shi Y, Ma G. et al. Positively charged polyprodrug amphiphiles with enhanced drug loading and reactive oxygen species-responsive release ability for traceable synergistic therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:4164–71. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b01641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hua L, Wang Z, Zhao L, Mao HL, Wang GH, Zhang KR. et al. Hypoxia-responsive lipid-poly-(hypoxic radiosensitized polyprodrug) nanoparticles for glioma chemo- and radiotherapy. Theranostics. 2018;8:5088–105. doi: 10.7150/thno.26225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang YJ, Zhang T, Hou CL, Zu MH, Lu Y, Ma XB. et al. Mitochondria-specific anticancer drug delivery based on reduction-activated polyprodrug for enhancing the therapeutic effect of breast cancer chemotherapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:29330–40. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b10211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutta D, Ke WD, Xi LC, Yin W, Zhou M, Ge ZS. Block copolymer prodrugs: synthesis, self-assembly, and applications for cancer therapy. Wiley Interdiscip Rev: Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2019: e1585. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Guo D, Xu S, Huang Y, Jiang H, Yasen W, Wang N. et al. Platinum(IV) complex-based two-in-one polyprodrug for a combinatorial chemo-photodynamic therapy. Biomaterials. 2018;177:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Ke W, Wang L, Huang M, Yin W, Zhang P. et al. Self-sufficing H2O2-responsive nanocarriers through tumor-specific H2O2 production for synergistic oxidation-chemotherapy. J Control Release. 2016;225:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang S, Yu G, Wang Z, Jacobson O, Lin LS, Yang W. et al. Enhanced antitumor efficacy by a cascade of reactive oxygen species generation and drug release. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2019;58:14758–63. doi: 10.1002/anie.201908997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin H, Sun M, Shi L, Zhu X, Huang W, Yan D. Reduction-responsive amphiphilic polymeric prodrugs of camptothecin-polyphosphoester for cancer chemotherapy. Biomater Sci. 2018;6:1403–13. doi: 10.1039/c8bm00162f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Li Y, Wang Y, Ke W, Chen W, Wang W. et al. Polymer prodrug-based nanoreactors activated by tumor acidity for orchestrated oxidation/chemotherapy. Nano Lett. 2017;17:6983–90. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b03531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun P, Wang N, Jin X, Zhu X. "Bottom-up" construction of hyperbranched poly(prodrug-co-photosensitizer) amphiphiles unimolecular micelles for chemo-photodynamic dual therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:36675–87. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b13055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo Z, Lin L, Hao K, Wang D, Liu F, Sun P. et al. Helix self-assembly behavior of amino acid-modified camptothecin prodrugs and its antitumor effect. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12:7466–76. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b21311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang S, Huang P, Chen X. Hierarchical targeting strategy for enhanced tumor tissue accumulation/retention and cellular internalization. Adv Mater. 2016;28:7340–64. doi: 10.1002/adma.201601498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gullotti E, Yeo Y. Extracellularly activated nanocarriers: a new paradigm of tumor targeted drug delivery. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2009;6:1041–51. doi: 10.1021/mp900090z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang RH, Kroll AV, Gao W, Zhang L. Cell membrane coating nanotechnology. Adv Mater. 2018;30:1706759. doi: 10.1002/adma.201706759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang S, Yu G, Wang Z, Jacobson O, Tian R, Lin LS. et al. Hierarchical tumor microenvironment-responsive nanomedicine for programmed delivery of chemotherapeutics. Adv Mater. 2018;30:1803926. doi: 10.1002/adma.201803926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin Q, Deng Y, Chen X, Ji J. Rational design of cancer nanomedicine for simultaneous stealth surface and enhanced cellular uptake. ACS Nano. 2019;13:954–77. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b07746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu YQ, Chen C, Cao ZY, Shen S, Li LS, Li DD. et al. On-demand PEGylation and dePEGylation of PLA-based nanocarriers via amphiphilic mPEG-TK-Ce6 for nanoenabled cancer chemotherapy. Theranostics. 2019;9:8312–20. doi: 10.7150/thno.37128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang P, Jain P, Tsao C, Yuan ZF, Li WC, Li BW. et al. Polypeptides with high zwitterion density for safe and effective therapeutics. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2018;57:7743–7. doi: 10.1002/anie.201802452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laschewsky A. Structures and synthesis of zwitterionic polymers. Polymers. 2014;6:1544–601. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu XS, Li H, Chen YJ, Jin Q, Ren KF, Ji J. Mixed-charge nanoparticles for long circulation, low reticuloendothelial system clearance, and high tumor accumulation. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2014;3:1439–47. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu ZZ, Gan ZY, Chen B, Chen F, Cao J, Luo XL. pH/redox dual-responsive amphiphilic zwitterionic polymers with a precisely controlled structure as anti-cancer drug carriers. Biomater Sci. 2019;7:3190–203. doi: 10.1039/c9bm00407f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piao JG, Gao F, Li YN, Yu L, Liu D, Tan ZB. et al. pH-sensitive zwitterionic coating of gold nanocages improves tumor targeting and photothermal treatment efficacy. Nano Res. 2018;11:3193–204. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim H, Cho MH, Choi HS, Lee BI, Choi Y. Zwitterionic near-infrared fluorophore-conjugated epidermal growth factor for fast, real-time, and target-cell-specific cancer imaging. Theranostics. 2019;9:1085–95. doi: 10.7150/thno.29719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng T, Wang WT, Wu F, Zhang M, Shen J, Sun Y. Zwitterionic polymer-gated Au@TiO2 core-shell nanoparticles for imaging-guided combined cancer therapy. Theranostics. 2019;9:5035–48. doi: 10.7150/thno.35418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Liu R, Shi Y, Zhang Z, Zhang X. Zwitterionic poly (carboxybetaine)-based cationic liposomes for effective delivery of small interfering RNA therapeutics without accelerated blood clearance phenomenon. Theranostics. 2015;5:583–96. doi: 10.7150/thno.11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishida T, Harada M, Wang XY, Ichihara M, Irimura K, Kiwada H. Accelerated blood clearance of PEGylated liposomes following preceding liposome injection: Effects of lipid dose and PEG surface-density and chain length of the first-dose liposomes. J Control Release. 2005;105:305–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han HS, Martin JD, Lee J, Harris DK, Fukumura D, Jain RK. et al. Spatial charge configuration regulates nanoparticle transport and binding behavior in vivo. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:1414–9. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mizuhara T, Saha K, Moyano DF, Kim CS, Yan B, Kim Y-K. et al. Acylsulfonamide-functionalized zwitterionic gold nanoparticles for enhanced cellular uptake at tumor pH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2015;54:6567–70. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Du JZ, Sun TM, Song WJ, Wu J, Wang J. A tumor-acidity-activated charge-conversional nanogel as an intelligent vehicle for promoted tumoral-cell uptake and drug delivery. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;122:3703–8. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuan YY, Mao CQ, Du XJ, Du JZ, Wang F, Wang J. Surface charge switchable nanoparticles based on zwitterionic polymer for enhanced drug delivery to tumor. Adv Mater. 2012;24:5476–80. doi: 10.1002/adma.201202296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Du J-Z, Li H-J, Wang J. Tumor-acidity-cleavable maleic acid amide (TACMAA): a powerful tool for designing smart nanoparticles to overcome delivery barriers in cancer nanomedicine. Acc Chem Res. 2018;51:2848–56. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen J, Guo Z, Jiao Z, Lin L, Xu C, Tian H, Poly(l-glutamic acid)-based zwitterionic polymer in a charge conversional shielding system for gene therapy of malignant tumors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Du JZ, Du XJ, Mao CQ, Wang J. Tailor-made dual pH-sensitive polymer-doxorubicin nanoparticles for efficient anticancer drug delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:17560–3. doi: 10.1021/ja207150n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu X, Hu J, Tian J, Ge Z, Zhang G, Luo K. et al. Polyprodrug amphiphiles: hierarchical assemblies for shape-regulated cellular internalization, trafficking, and drug delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:17617–29. doi: 10.1021/ja409686x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu X, Liu G, Li Y, Wang X, Liu S. Cell-penetrating hyperbranched polyprodrug amphiphiles for synergistic reductive milieu-triggered drug release and enhanced magnetic resonance signals. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:362–8. doi: 10.1021/ja5105848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guo X, Wang L, Duval K, Fan J, Zhou S, Chen Z. Dimeric drug polymeric micelles with acid-active tumor targeting and FRET-traceable drug release. Adv Mater. 2018;30:1705436. doi: 10.1002/adma.201705436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang D, Li L, Ji XH, Gao YH. Intracellular GSH-responsive camptothecin delivery systems. New J Chem. 2019;43:18673–84. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dai Y, Yang Z, Cheng S, Wang Z, Zhang R, Zhu G. et al. Toxic reactive oxygen species enhanced synergistic combination therapy by self-assembled metal-phenolic network nanoparticles. Adv Mater. 2018;30:1704877. doi: 10.1002/adma.201704877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang W, Yang Z, Wang S, Wang Z, Song J, Yu G. et al. Organic semiconducting photoacoustic nanodroplets for laser-activatable ultrasound imaging and combinational cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2018;12:2610–22. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b08628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.