Dear Editor,

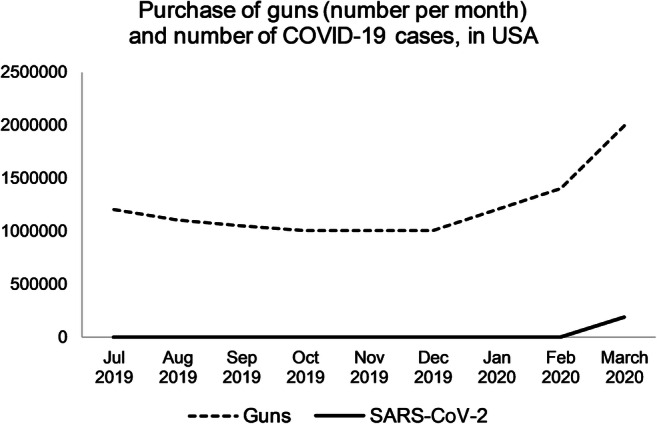

Globally, 857 million civilians have firearms with half concentrated in the United States, representing an illicit and illegal market of several billions of dollars. Since 1791, the Second Amendment of the United States Constitution authorized laws to own and use guns, involving the highest rate of civilian firearm holdings around the world (i.e., 120 firearms per 100 people) (Karp 2018). Each year, 50,000 people die or are injured by gun violence in the USA, including 15,000 homicides, 20,000 suicides, and 4000 child deaths (Gun violence archive 2019). The first confirmed case of coronavirus in the USA was on January 19, 2020 (Holshue et al. 2020). Since this first reported case, the severe acute respiratory syndrome related to coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic spread across the USA causing 100,000 cases resulting in several thousand deaths. In the same period, gun violence was responsible for more than 16,000 deaths or injuries. Increases in fear and paranoia became prominent among US citizens, promoting the desire for self-defense, with an increase in recorded gun sales of one million in March 2020 (Fig. 1). The crowded cities of the USA are susceptible to gun violence where poverty, ghettoization, drug trafficking, and gang warfare are killing children and teenagers (Crifasi et al. 2018). Moreover, there is a 3-fold increase in homicide and suicides when individuals have direct access to firearms (Anglemyer et al. 2014). This is in addition to increases in domestic violence against women (Goodyear et al. 2019). Firearm injuries need intensive care units (ICUs) to manage the injury to vital organs and provide surgical procedures (i.e., orthopedic, abdominal, and vascular). USA is particularly exposed to civilian public mass shooting caused by easy access to semi-automatic military rifles (de Jager et al. 2018; de Jager et al. 2019; Sarani et al. 2019). Synthesized data highlighted that semi-automatic assault rifles involved an increase of 91% in the number of persons wounded or killed, explained by special ballistic properties (Peled et al. 2012), facility of use, large magazines, and high-velocity bullets fired (de Jager et al. 2018; de Jager et al. 2019; Sarani et al. 2019). Thus, similar to in war situations, most victims of these military arms require ICU and surgical management to control massive internal and external bleeding, failure of vital organs, and comminuted fractures of the skeleton (Peled et al. 2012). However, ICUs are vital in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic with a shortage of assisted ventilation and health care workers. An estimated 800,000 hospital beds are available in the USA, of which 10% are in ICUs (American Hospital Association 2020). Considering a 65% utilization rate for bed occupancy during routine practice, the 30,000 beds remaining in ICUs will rapidly become occupied by severely ill SARS-CoV-2 patients in the very near future (National Center for Health Statistics (US) 2019). As so succinctly urged by Dr. Elinore Kaufman, a trauma surgeon in Philadelphia, “Save hospital resources for Covid-19 patients by putting your guns down” (Kaufman 2020).

Fig. 1.

Purchase of guns (number per month) and number of COVID-19 cases in the USA

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Hospital Association . AHA hospital statistics. Chicago: American Hospital Association; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Anglemyer A, Horvath T, Rutherford G. The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(2):101–110. doi: 10.7326/M13-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crifasi CK, Merrill-Francis M, McCourt A, et al. Association between firearm laws and homicide in urban counties. J Urban Health. 2018;95(3):383–390. doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-0273-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jager E, Goralnick E, McCarty JC, et al. Lethality of civilian active shooter incidents with and without semiautomatic rifles in the United States. JAMA. 2018;320(10):1034–1035. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.11009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jager E, McCarty JC, Jarman MP, et al. US civilian active shooter incidents involving a semiautomatic rifle are more lethal than incidents involving other firearms. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;229(3):323. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear A, Rodriguez M, Glik D (2019). The role of firearms in intimate partner violence: policy and research considerations. Journal of Public Health Policy. (Consulté le avril 4, 2020); Disponible sur: http://link.springer.com/10.1057/s41271-019-00198-x (Consulté le avril 4, 2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gun violence archive (2019). Evidence Based Research - since 2013. Disponible sur: https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/.

- Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp A. (2018). Estimating global civilian-held firearms numbers. Small Arms Survey. Disponible Sur. http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/fileadmin/docs/T-Briefing-Papers/SAS-BP-Civilian-Firearms-Numbers.pdf.

- Kaufman E. (2020). Please, Stop Shooting. We Need the Beds. The New York Times. Disponible sur: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/01/opinion/covid-gun-violence-hospitals.html.

- National Center for Health Statistics (US) Health, United States, 2018. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics (US); 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peled M, Leiser Y, Emodi O, et al. Treatment protocol for high velocity/high energy gunshot injuries to the face. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2012;5(1):31–40. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1293518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarani B, Hendrix C, Matecki M, et al. Wounding patterns based on firearm type in civilian public mass shootings in the United States. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;228(3):228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]