Abstract

The Mizoroki–Heck reaction is one of the most studied palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, representing a powerful method for forming C–C bonds between diverse substrates with broad functional group compatibility. However, the reductive variant has received considerably less attention. In this Review, we summarize distinct mechanistic aspects of the reductive Heck reaction, highlight recent contributions to the field, and discuss potential applications of the reductive Heck reaction in the pharmaceutical industry. With the potential to have a large impact in both academic and industrial settings, further development of the reductive Heck reaction is a promising area of future investigation.

Keywords: palladium, Heck reaction, alkene functionalization, hydroarylation

Mizoroki-Heck vs. Reductive Heck.

The Mizoroki–Heck coupling of aryl halides and alkenes to form C(sp2)–C(sp2) bonds has become a staple transformation in organic synthesis, owing to its broad functional group compatibility and varied scope [1–10]. In stark contrast, the palladium-catalyzed reductive Heck reaction has received considerably less attention, despite the fact that early reports of this reaction date back almost half a century. From the perspective of retrosynthetic logic, this transformation is highly enabling because it can forge alkyl–aryl linkages from widely available alkenes, rather than from the less accessible and/or more expensive alkyl halide or organometallic C(sp3) synthons that are needed in a classical aryl/alkyl cross-coupling.

In part due to the historical difficulties of developing a generally applicable palladium(0)-catalyzed reductive Heck protocol that is compatible with diverse alkenes (vide infra), various alternative strategies to achieve alkene hydroarylation (see Glossary) have been developed. These include dual catalytic approaches [11, 12], reactions involving other metals [13–16], and mechanistically distinct palladium-catalyzed methods [17–20]. While useful in their own right, these catalytic reactions are outside of the scope of this review. The purpose of this review will be to cover the historical development of the palladium-catalyzed reductive Heck reaction in order to contextualize recent and ongoing work in the field. In addition, potential applications and advantages of the palladium-catalyzed reductive Heck reaction in the pharmaceutical industry will be discussed.

Mechanistic Overview.

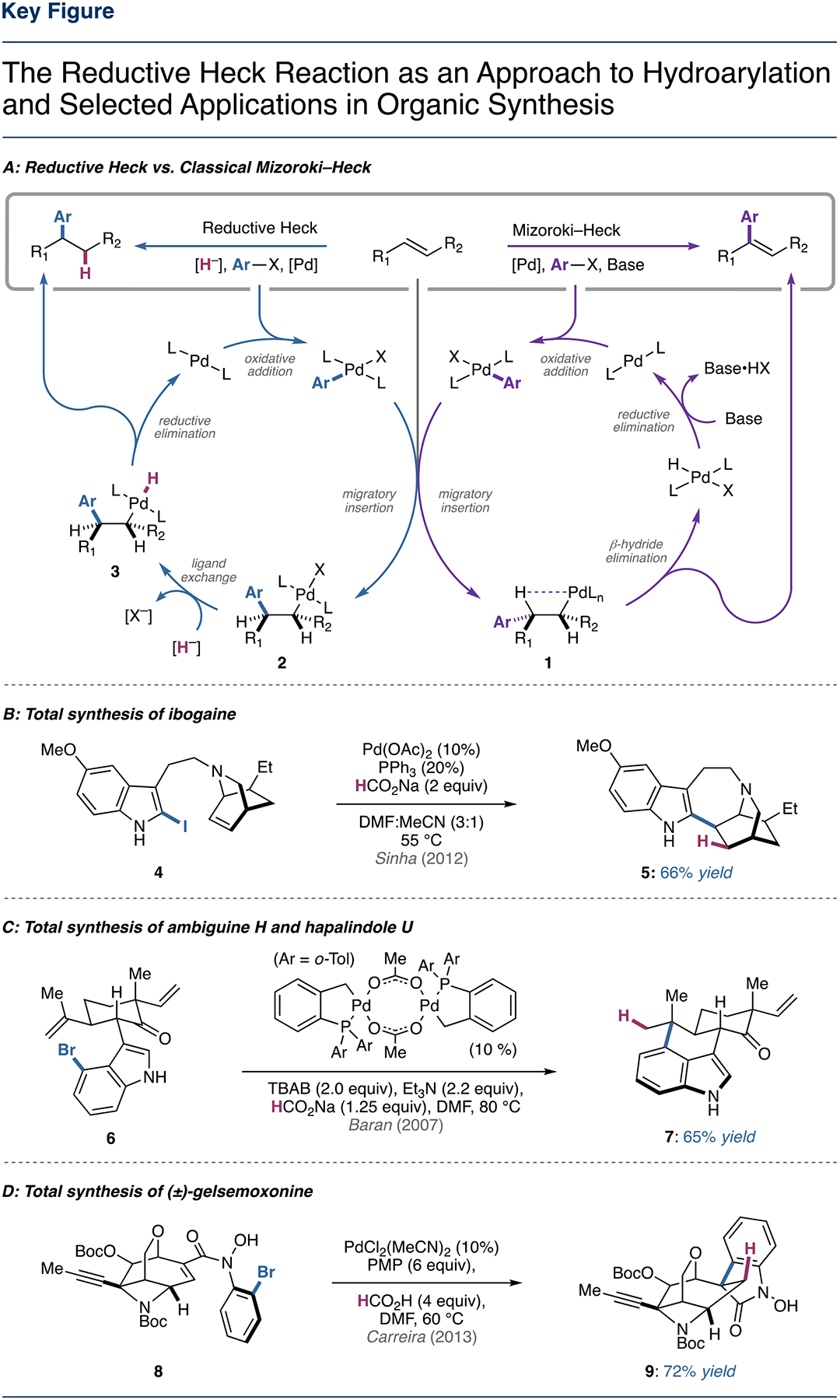

Based on various experimental observations, it has been proposed that the operative mechanism of the conventional Mizoroki–Heck reaction varies subtly depending on the reaction conditions [21]; however, the general mechanism is as follows (Figure 1A, right): the catalytic cycle begins with oxidative addition of a C(sp2)–X (X = Br, Cl, I, OTf, etc.) bond to a palladium(0) complex followed by 1,2-migratory insertion to access an alkylpalladium(II) intermediate (1). This C(sp3)–PdII intermediate then succumbs to rapid β-hydride elimination to deliver the functionalized alkene product, followed by regeneration of palladium(0) via HX reductive elimination.

Figure 1. Mechanistic Overview and Applications in Synthesis.

(A) The reductive Heck (left) and classical Mizoroki-Heck (right) approaches to alkene functionalization. (B) Application of the reductive Heck reaction in the total synthesis of ibogaine. (C) Application of the reductive Heck reaction in the total synthesis of ambiguine H and hapalindole U. (D) Application of the reductive Heck reaction in the total synthesis of (±)-gelsemoxonine.

The reductive Heck reaction follows a similar mechanism (Figure 1A, left), but involves intercepting the alkylpalladium(II) intermediate (2) with a hydride source (most commonly formate) to form a palladium complex (3) that can readily undergo reductive cleavage to form a new C–H bond [22]. Favoring the reductive pathway can be challenging due to competing β-hydride elimination; however, conformationally restricted olefins with the absence of β-hydrogens syn-periplanar relative to the C(sp3)–PdII can render β-hydride elimination inoperable. Additionally, substrates that have the ability to form stabilized π-allyl/π-benzyl/enolate intermediates can also react to give formal reductive Heck products. More recently, protocols have been developed that allow for reductive Heck coupling of unactivated aliphatic and heteroatom-substituted alkenes, which will be discussed (vide infra).

Reactions with Strained Alkenes.

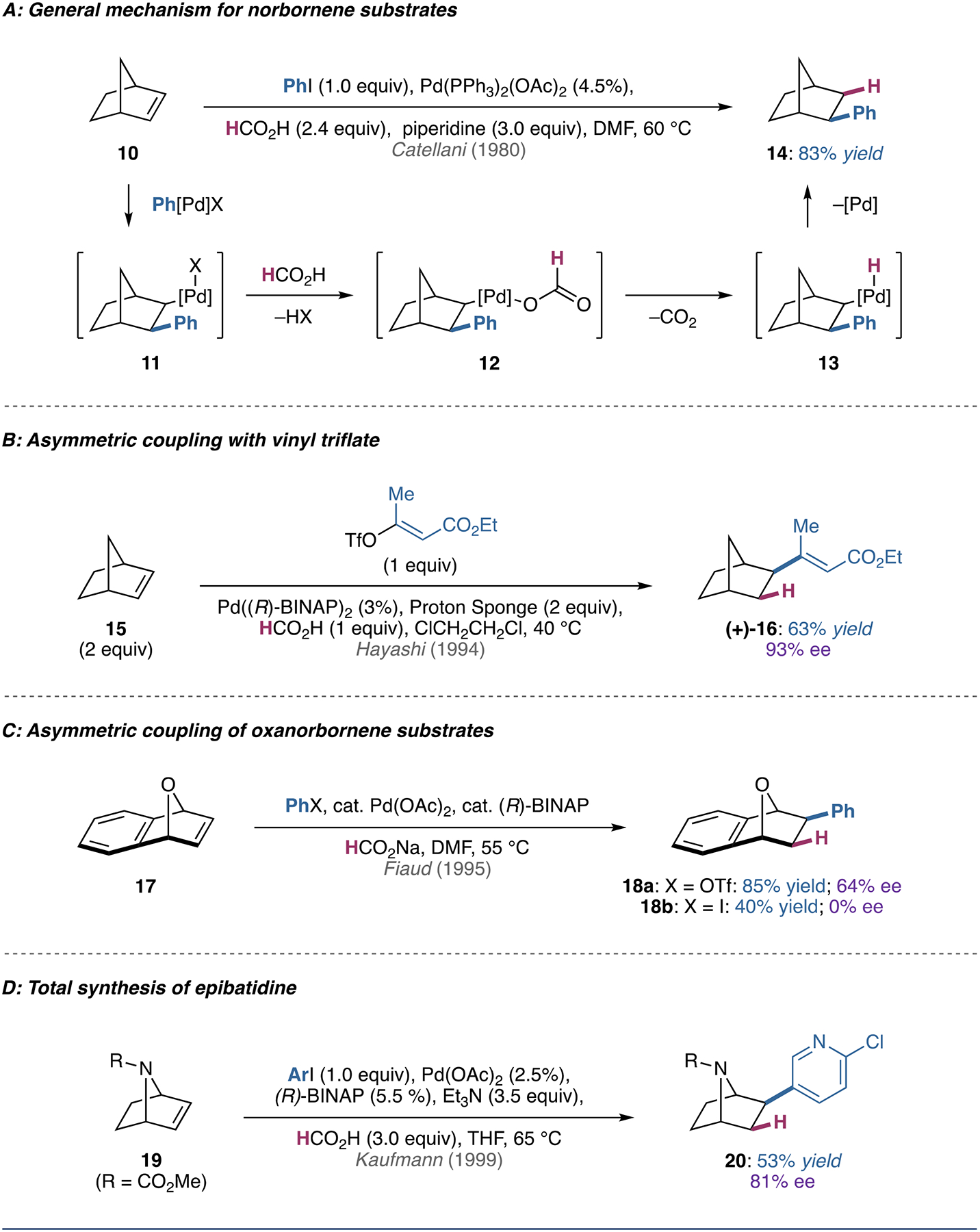

In a seminal study in 1980, Catellani took advantage of the diastereospecificity of migratory insertion and β-hydride elimination with norbornene substrates, allowing interception of the alkylpalladium(II) intermediate 11 (Figure 2A) [23]. In these systems, ligand exchange of the halide with formate results in formation of the norbornyl palladium species (12), which undergo decarboxylation (12 → 13) and reductive elimination to afford the corresponding product. Later work improved the efficiency of the reaction with piperidine and tetraalkylammonium salt additives [24].

Figure 2. Reactions with Strained Alkenes.

(A) Illustration of the diastereospecificity of migratory insertion and β-hydride elimination with norbornene substrates. (B) Seminal example of asymmetric coupling between a vinyl triflate and a norbornene substrate. (C) Illustrative example of the influence of the halide/pseudohalide used in the reductive Heck reaction of an oxanorbornene substrate. (D) Application of the reductive Heck reaction in the total synthesis of epibatidine from a protected azanorbornene.

Asymmetric reductive Heck couplings of norbornene scaffolds were first reported in 1991 using (R,R)-NorPhos, albeit with moderate enantioselectivity [25]. Subsequent reports (Figure 2B) found that enantioinduction could be improved through judicious choice of ligand (switching to P,N- or N,N- type ligands) and coupling partners (use of triflates over iodides) [26–32]. The latter observation has been posited to arise from a suppression of competing reduction of the C(sp3)–PdII intermediate prior to alkene insertion [33].

Following the successful development of asymmetric reductive Heck couplings on norbornene, this strategy was soon extended to oxanorbornene and azanorbornene substrates. Although the exact conditions and absolute configurations are not reported, Fiaud and coworkers reported an interesting observation regarding the reductive Heck arylation of 17 [34]. Enantioselectivity was strongly influenced by the nature of the halide/pseudohalide employed, with aryl triflates coupling partners giving moderate enantiomeric excess (ee) while aryl iodides demonstrated no enantioinduction (Figure 2C). This supports hypotheses of both cationic and neutral pathways analogous to the classic Mizoroki–Heck reaction [7, 8]. The asymmetric coupling of azanorbornene scaffolds has also been successful. In particular, the reductive Heck coupling of azanorbornene 19 has allowed for short, enantioselective syntheses of the alkaloid epibatidine and structural analogues (Figure 2D) [35–38]. Further, a strategy to access the natural product ibogaine and analogues (Figure 1B) [39] involves an intramolecular reductive Heck reaction facilitated by a tether, a strategy that has also been extended to non-strained alkenyl systems (vide infra).

Reactions with Styrenes.

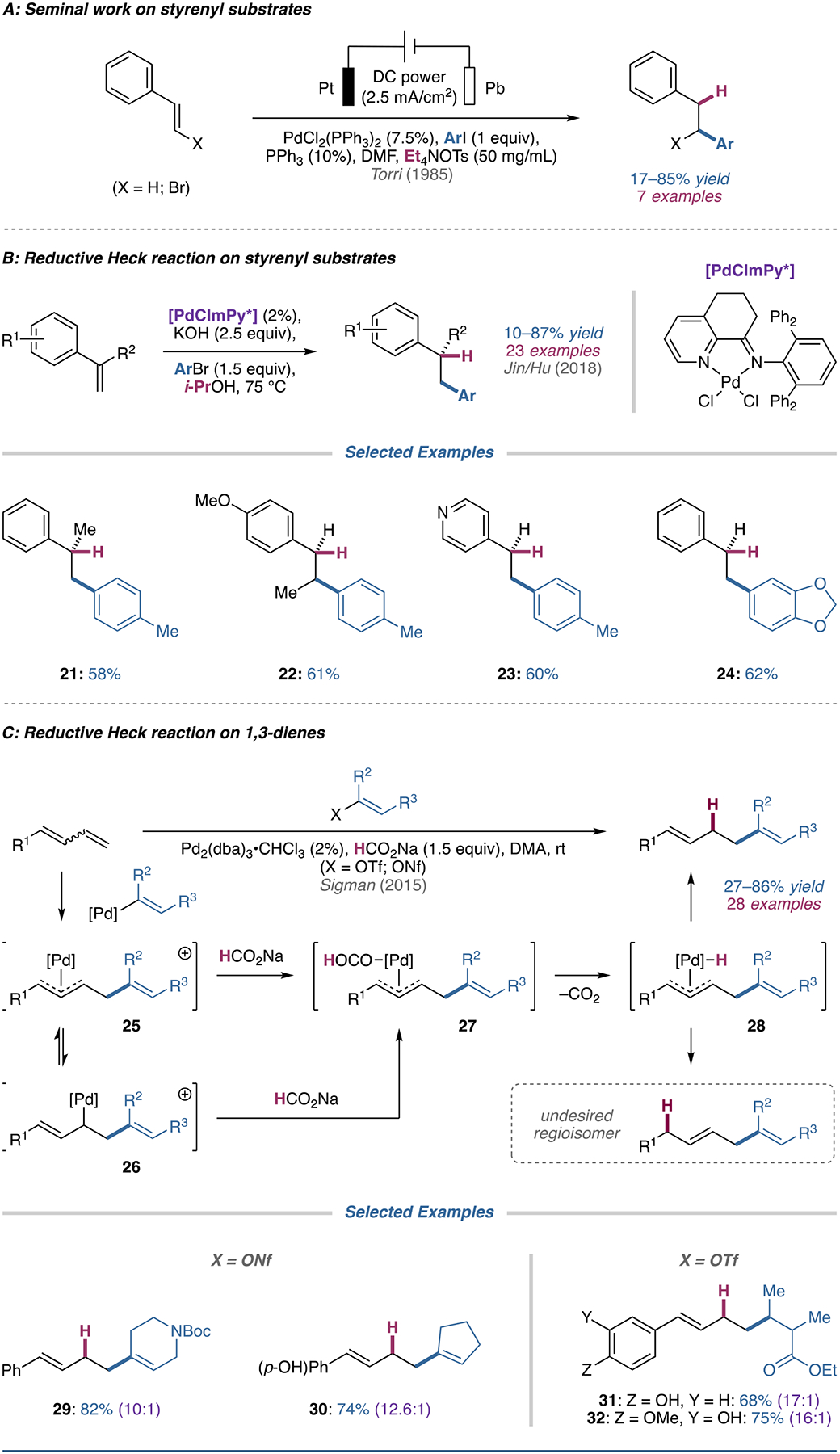

Reductive Heck hydroarylation of styrenes was first reported by Torri and colleagues in 1985 (Figure 3A) [40]. The reaction gives hydroarylated products in good yields and with high regioselectivity, albeit only with conjugated olefins. Despite being one the first reports of a reductive Heck hydroarylation, Torri’s work remains the only example proceeding via an electro-reductive mechanism.

Figure 3. Reactions with Styrenes.

(A) Torri’s seminal work on the electro-reductive Heck reaction of styrenyl substrates. (B) Reductive Heck couplings between styrenes and aryl bromides. (C) Reductive Heck reactions of 1,3-dienes proceeding through a π-allyl intermediate.

Recently, Jin, Hu, and coworkers reported a reductive Heck coupling between styrenyl substrates and aryl bromides (the conditions also allow for unactivated C(sp2)–C(sp3) coupling, covered later in the review) [41]. As shown by 21 and 22, methyl substitution was tolerated at the branched and terminal position of the alkene; however, phenyl substitution at these positions resulted in a significant decrease in yield, (19% and 10% for the branched and terminal positions, respectively). Other styrenyl-type substrates like 23 were compatible, as were some additional aryl bromide coupling partners (24). Kinetic and deuterium labeling experiments suggested that i-PrOH provides a hydride through β-H elimination.

Sigman and coworkers have developed a reductive Heck protocol for 1,3-dienes [42]. Based on previous work on similar systems, the authors posit that the transformation involves oxidative addition of an enol triflate or nonaflate with Pd(0) to form a cationic palladium complex that can undergo migratory insertion into a 1,3-diene. The migratory insertion intermediate (26) is in equilibrium with a π-allyl intermediate (25), which is subsequently trapped by the hydride source. Reductive elimination yields tri- and tetrasubstituted alkenes in moderate to good yields and selectivity.

Reactions with Tethered Alkenes.

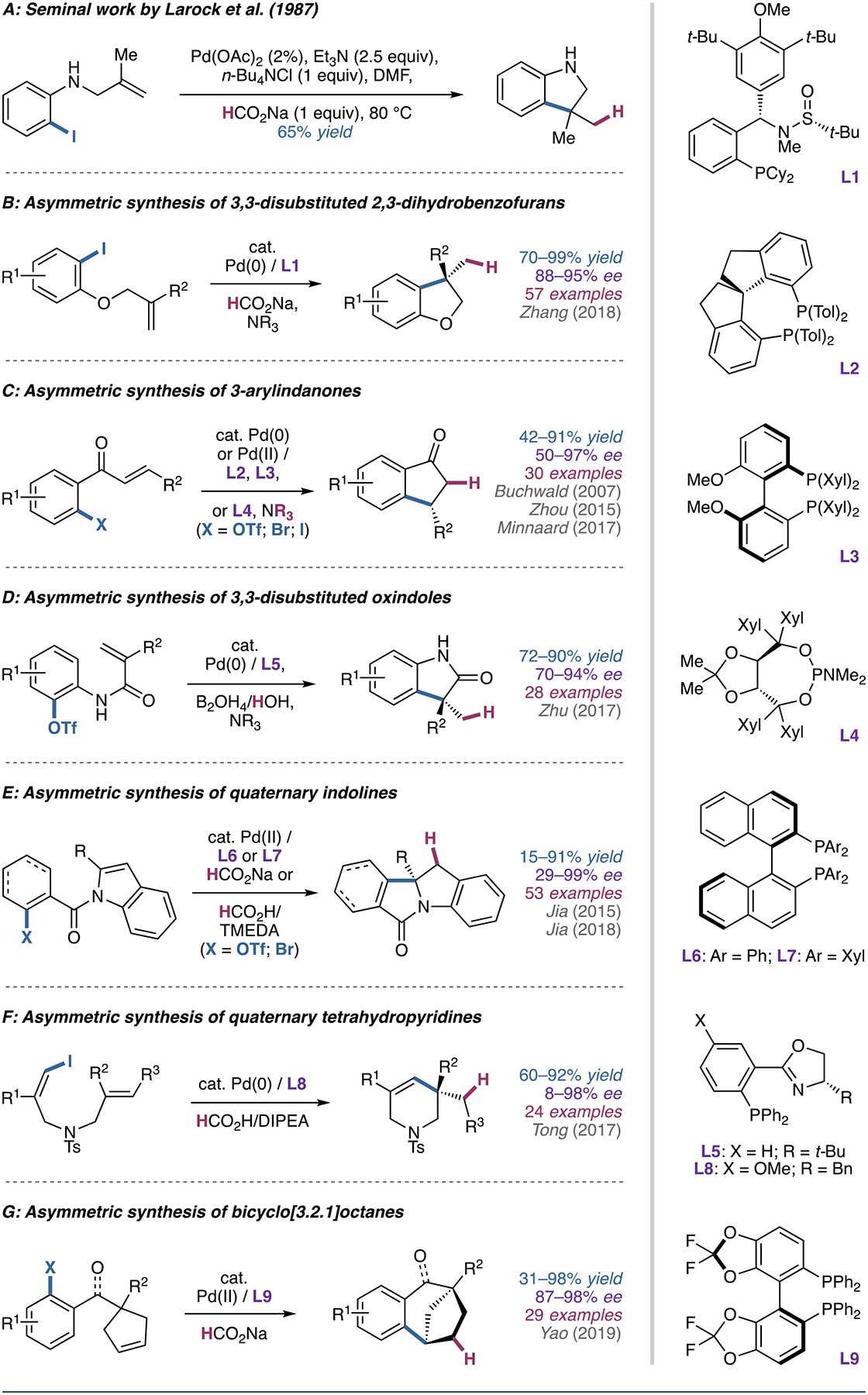

The bulk of the work completed on the reductive Heck reaction has been focused on enabling access to highly functionalized heterocyclic cores through a potentially enantioselective, transition-metal-catalyzed process. Larock’s seminal work on the preparation of indoline through a reductive Heck process (Figure 4A) [43] laid the groundwork for rapidly generating heterocycles. Although Larock did not employ a chiral ligand, recent advances in the field suggest that an asymmetric variant could be developed to afford enantioenriched indolines, structures that are of interest to the pharmaceutical industry [44, 45].

Figure 4. Reactions with Tethered Alkenes.

(A) Larock’s seminal work on heterocycle synthesis using the reductive Heck reaction. (B) The asymmetric reductive Heck cyclization to form 3,3-disubstituted 2,3-dihydrobenzofurans. (C) The asymmetric reductive Heck cyclization to access 3-arylindanones. (D) The asymmetric reductive Heck cyclization to form 3,3-disubstituted oxindoles. (E) The asymmetric reductive Heck cyclization to access quaternary indanones. (F) The asymmetric reductive Heck cyclization to form quaternary tetrahydropyridines. (G) The asymmetric reductive Heck cyclization to access bicyclo[3.2.1]octanes.

The first asymmetric reductive Heck coupling of a tethered alkene was reported in 1998 by Diaz and coworkers en route to conformationally restricted retinoids [46]. This work only featured two examples and required the addition of calcium carbonate and silver-exchanged zeolites to give ee’s of 69% and 81%. Recent work by Zhang and coworkers using chiral sulfonamide phosphine ligands has improved the reaction to feature a broad substrate scope and high enantioselectivity (88–95% ee) without the use of stoichiometric silver additives (Figure 4B) [47].

In 2007, Buchwald and coworkers reported the synthesis of 3-arylindanones via an asymmetric reductive Heck cyclization using chiral biaryl phosphine ligands to couple aryl triflates or nonaflates [48]. While pseudohalide substrates gave generally good yields and moderate enantioselectivity (50–94% ee), the use of aryl halides resulted in low conversion. The authors propose that hydride transfer to palladium occurs from the α-proton of the trialkylamine base, in this case Proton Sponge (1,8-bis(dimethylamino)naphthalene).

Later work by Zhou (54–97% ee with biaryl phosphine ligands) [49] and Minnaard (86–90% ee with monodentate phosphoramidite ligands) [50] extended the scope to aryl bromides and iodides, respectively; however, it should be noted that the aryl bromide substrates required 1 equivalent of benzoic acid additive in order to obtain high yields and enantioselectivity (Figure 4C).

In their work on asymmetric reductive Heck cyclization to access 3,3-disubstituted oxindoles (Figure 4D), Zhu and coworkers reported the only reductive Heck system to date that uses diboron/water as a hydride source [51]. Using a chiral phosphinooxazoline ligand to couple aryl triflates afforded the desired oxindole products in high yields and enantioselectivity (70–94% ee). Notably, deuterium-labeled compounds are accessible by using D2O in the reaction, allowing easy access to deuterated chiral oxindoles.

In 2015, Jia and colleagues reported an asymmetric dearomatization of indoles via an intramolecular reductive Heck reaction to yield quaternary indolines (Figure 4E) [52]. Using a chiral biaryl phosphine ligand and sodium formate (without trialkylamine additive) to couple aryl bromide substrates with a tethered indole moiety yielded the desired indoline products in moderate yields and high enantioselectivity (89–99% ee) in the absence of ortho-substitution on the bromobenzoyl ring. The presence of an ortho-methyl group resulted in significantly diminished yield (22%) and ee (29%). Subsequent work employing TMEDA/HCO2H as the reductant extended the scope of the reaction to tethered alkenyl bromides (93–99% ee) [53].

Recently, Tong and coworkers reported an asymmetric reductive Heck cyclization to afford quaternary tetrahydropyridines (Figure 4F) [54]. Using a chiral phosphinooxazoline ligand with DIPEA/HCO2H as the reductant, (Z)-1-iodo-1,6-dienes were cyclized to the corresponding tetrahydropyridines in good yields and enantioselectivity (71–99% ee). Notably, only 1,1-disubstituted and 1,1,2-trisubstituted alkenes afforded good yields and enantioselectivity. In addition, oxygen linked substrates exhibited similar reactivity, albeit with significantly diminished enantioselectivity (8–63% ee).

In 2019, Yao and colleagues reported a reductive Heck desymmetrization of cyclopentenes to access enantioenriched bicyclo[3.2.1]octanes (Figure 4G) [55]. A chiral bisphosphine ligand with sodium formate as the reductant yielded the desired products in good yields and high enantioselectivity. Like other systems, the presence of an ortho-methyl group (relative to the halogen) resulted in significantly diminished yield; however, the reaction was tolerant of a wide variety of other functional groups at various positions.

Reactions with Tethered Alkenes in Synthesis.

The intramolecular reductive Heck cyclization of tethered alkenes has seen extensive use in total synthesis [56–63]. One such illustrative example is seen in the synthesis of ambiguine H and hapalindole U (Figure 1C) [64, 65]. Baran and coworkers observed preferential formation of the undesired 7-endo-trig product and debromination when employing radical conditions on substrate 4; however, the desired 6-exo-trig cyclization was successfully observed when employing reductive Heck conditions. After extensive optimization, catalyst turnover remained relatively poor with various common palladium pre-catalysts, which the authors attributed to catalyst decomposition in the highly reducing environment. Slow addition of the more robust Herrmann’s palladacycle was found to elicit full consumption of the starting material to give product 5 in 65% isolated yield on gram-scale. A recent report by Snyder and coworkers uses almost identical reductive Heck conditions to construct a quaternary center en route to the conidiogenone natural products [56].

In the Carreira synthesis of (±)-gelsemoxonine, a diastereoselective reductive Heck cyclization was used to form a key oxindole ring in 72% yield as a single diastereomer (Figure 1D) [66]. Notably, the reductive Heck conditions avoid undesired side reactivity including β-hydride elimination, destruction of the adjacent azetidine ring, and cleavage of the N−O and oxabicyclic C−O bonds.

Reactions with α,β-Unsaturated Enones/Enals.

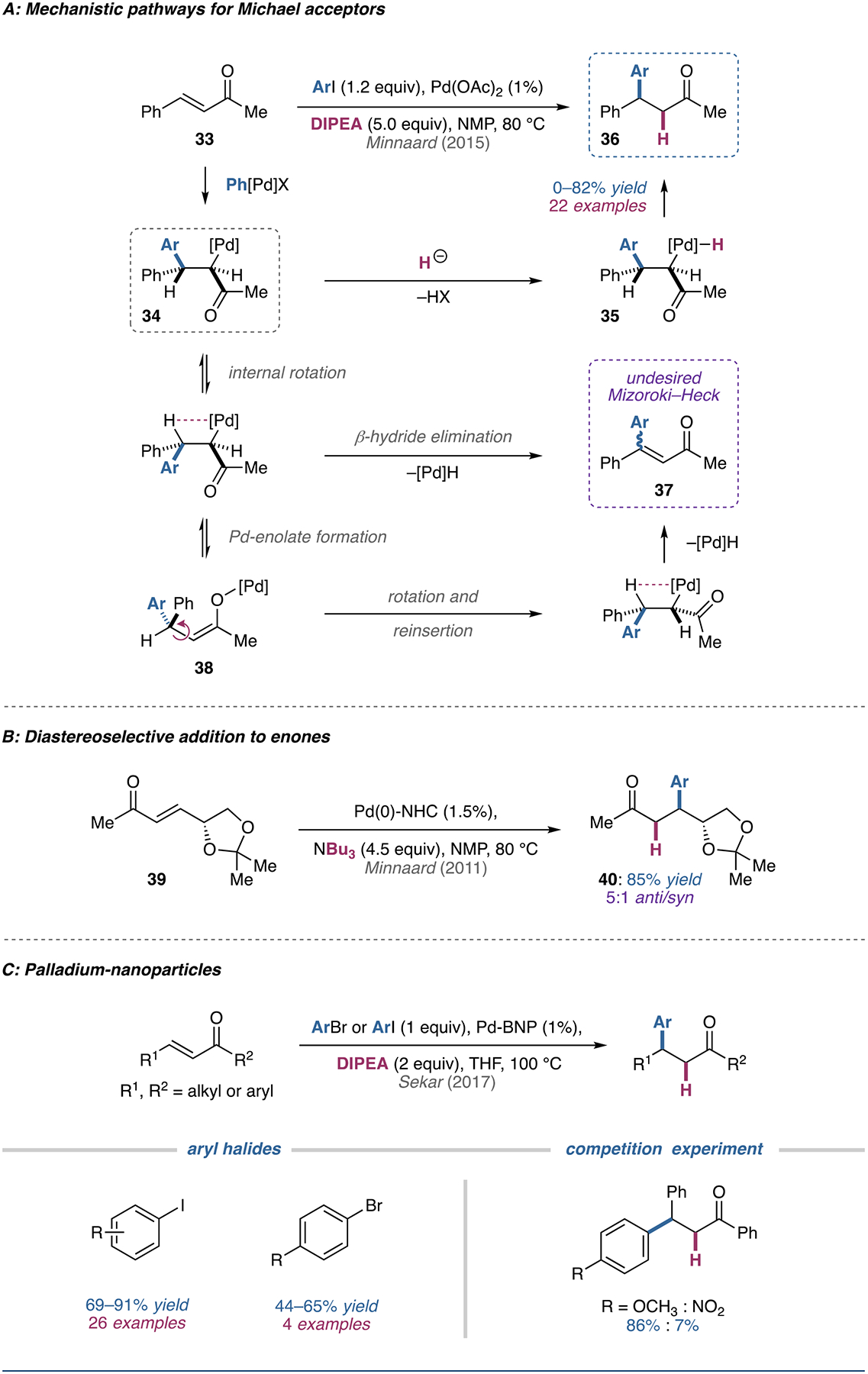

In 1983, Cacchi and coworkers disclosed a reductive Heck arylation of enones and enals in the presence of a trialkylamine base, tetrabutylammonium halide, and formic acid additive [67]. Under these conditions, the conjugate addition product is formed preferentially to the vinylic substitution (Mizoroki–Heck) product in high yield and selectivity. Notably, reductive Heck coupling on enones/enals features some mechanistically distinct aspects, as described in studies by Cacchi and later Minnaard (Figure 5A) [68–75].

Figure 5. Reactions with α,β-Unsaturated Enones/Enals.

(A) Mechanistic pathways for the reductive Heck reaction of Michael acceptors proposed by Cacchi and Minnaard. (B) Example of diastereoselectivity in the reductive Heck reaction of a D-mannitol-derived enone. (C) Examples of reductive Heck reactivity in conjugate additions catalyzed by binaphthyl-backbone-stabilized palladium nanoparticles.

Both the conjugate addition and vinylic substitution mechanisms proceed through a common alkylpalladium(II) intermediate 34. In the case of vinylic substitution, internal bond rotation can result in the required syn-periplanar geometry necessary for β-hydride elimination to deliver the functionalized alkene product 37. A mixture of E/Z isomers is obtained due to the formation of a palladium enolate species (38), which facilitates reinsertion without facial preference.

In the conjugate addition case, intermediate 34 can be intercepted with formic acid to form a palladium complex (35) that can readily undergo reductive cleavage to form the new C–H bond. Control experiments run with added Heck product have ruled out the occurrence of a tandem Mizoroki–Heck reaction followed by degenerate reduction of the alkene by a palladium–hydride species; furthermore, computational studies suggest that reductive cleavage of Pd (rather than protonolysis) results in the formation of the product.

Building on Cacchi’s original conditions, Minnaard and coworkers have introduced systems that do not require the addition of formic acid or tributylamine additives [76]. In Pd(OAc)2 or Pd(TFA)2 catalyzed reductive Heck reactions with aryl iodide coupling partners, N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) can serve as the reductant [77–81]. When using NMP as the solvent, electron-rich and electron-neutral aryl iodides gave good selectivity and moderate yields when coupling to enones with aryl/bulky substituents; however, selectivity and yield was diminished when coupling electron-deficient aryl iodides and when substrates featured non-bulky alkyl substituents on the β-carbon.

In a related system, N-heterocyclic carbene palladium complexes can be used in combination with various reductants in NMP or DMF to generate conjugate addition products (Figure 5B) [82]. The nature of the base has been shown to govern the course of the reaction, allowing preferential formation of either the classical Mizoroki–Heck or reductive Heck products. When applied to D-mannitol-derived substrate 39, the desired product 40 was formed diastereoselectively (5:1 anti/syn). Unfortunately, attempts to render the reductive Heck reaction enantioselective with both the N-heterocyclic carbene palladium complex and palladium acetate systems were not fruitful.

Recently, reductive Heck conjugate additions catalyzed by binaphthyl-backbone-stabilized palladium nanoparticles have been reported (Figure 5C) [83]. The reusable palladium nanocatalyst afforded good yields for both electron-rich and electron-poor aryl iodides as well as moderate yields for selected aryl bromides. While good yields are possible with both electron-rich and electron-poor aryl iodides, competition experiments showed that the rate is significantly faster for electron-rich aryl iodides.

Reactions with Terminal and Unactivated Alkenes.

While early reports of an intermolecular reductive Heck required activated alkenes or systems that lacked β-hydrogens, the recent development of a process employing terminal alkenes and iodoarenes has altered the landscape and offered new opportunities for advancing this promising methodology.

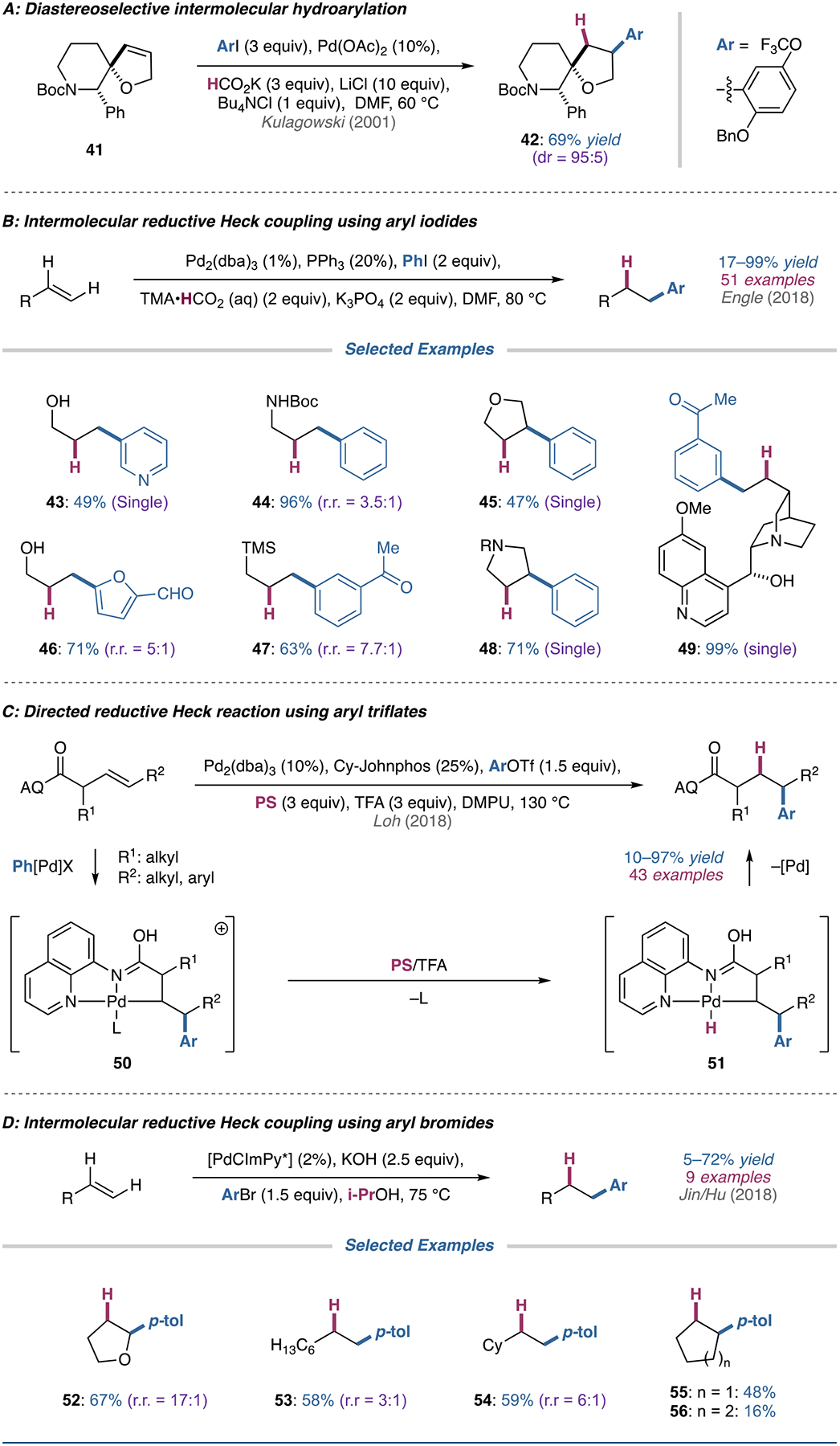

Chemists at Merck identified an opportunity to use a reductive Heck reaction in their retrosynthetic analysis of NK-1 receptor antagonist precursors (Figure 6A) [84]. The authors hypothesized that steric considerations in dihydrofuran 41 would limit the ability of the alkylpalladium intermediate to undergo β-hydride elimination (similar to the strategy invoked in the earlier discussed strained alkenes). This strategy did indeed furnish the desired product with the correct regio- and stereochemistry; however, the authors note that excess lithium chloride additive was required to prevent competing dehalogenation of the aryl iodide [85]. Notably, this is one of few examples of a diastereoselective intermolecular reductive Heck.

Figure 6. Reactions with Terminal and Unactivated Alkenes.

(A) Diastereoselective reductive Heck reaction used by chemists at Merck in the synthesis of NK-1 receptor antagonist precursors. (B) Regioselective reductive Heck coupling of cyclic and unactivated terminal alkenes with aryl iodides. (C) 8-aminoquinoline-directed reductive Heck reaction using aryl triflates. (D) Regioselective reductive Heck coupling of cyclic and unactivated terminal alkenes with aryl bromides.

In 2018, Engle and coworkers disclosed an intermolecular reductive Heck reaction of diverse terminal alkenes and select internal alkenes utilizing aqueous tetramethylammonium formate as the reductant (Figure 6B) [86]. This method tolerated an array of functional groups, including reductively labile groups, on both the (hetero)aryl iodide and alkene coupling partners, and was generally regioselective for the anti-Markovnikov product for terminal alkenes. A variety of terminal alkenes were compatible with the conditions, including simple α-olefins, heteroatom-substituted alkenes, and alkene-containing complex molecules such as quinine (49) and various terpenes.

In addition, cyclic internal alkenes (45 and 48) were suitable substrates, affording reasonable yields of product; however acyclic internal alkenes were poor substrates for the reaction in terms of yield and regioselectivity. Unique to this method, the authors discovered that a 10:1 phosphine to palladium loading was essential to achieve high yields and suppress the formation of Heck byproducts. The authors hypothesized that the high phosphine loading leads to coordinative saturation of the palladium center to prevent β-hydride elimination from the alkylpalladium(II) intermediate, allowing it to decarboxylate formate to produce a palladium–hydride that could reductively eliminate to give the desired product.

Recently, Wu, Loh, and coworkers reported an auxiliary-directed reductive Heck reaction of unactivated alkenes and aryl triflates utilizing proton sponge as the hydride source (Figure 6C) [87]. The authors rely on an 8-aminoquinoline directing group to control the regioselectivity of migratory insertion and stabilize the resulting alkylpalladium(II) intermediate (50). Both terminal β,γ- and γ,δ-alkenyl carbonyl compounds were suitable substrates for the reaction; however, internal alkenes proved to be more challenging to functionalize, with only β,γ-internal alkenes yielding products.

As previously mentioned, Jin, Hu, and coworkers developed a reductive Heck reaction of aryl bromides with styrenes (vide supra) and unactivated alkenes (Figure 6D) [41]. The reaction requires a preformed palladium catalyst comprised of a specialized bidentate constrained iminopyridyl (CImPy) ligand, which is believed to be vital for stabilizing the palladium center. The authors found that several simple α-olefins were suitable substrates for the reaction, providing reasonable yields with moderate regioselectivities. Both symmetric linear and cyclic alkenes were compatible substrates, although increasing the ring size of the cycloalkene resulted in diminished yields (55 vs. 56). In addition, using 2,3-dihydrofuran as a substrate afforded the 2-substituted tetrahydrofuran product (52) in good yield and high regioselectivity.

Prospects for Applications in the Pharmaceutical Industry.

As is evident from the examples above, reductive Heck hydroarylation can be an enabling disconnection that affords structures similar to those derived from other sp2-sp3 cross-coupling reactions, but with the benefit of simplifying the required starting material (in this case an alkene synthon). This synthetic logic holds substantial promise for applications in the pharmaceutical industry, despite its relatively limited application to date.

New synthetic methodologies are constantly required in the pharmaceutical sector due to the increasing diversity of chemical modalities used to treat human disease. The rate of exploration of new chemical space has significantly increased over the last few decades, which increases the complexity of the chemical structures being pursued [88]. This continuing evolution represents a consistent challenge to pharmaceutical chemists and demands new bond forming processes. The structural complexity of a molecule is often linked to the complexity of its synthesis, features which can be combined and measured by determining the molecule’s current complexity [89]. In this context, developing commercially viable, efficient and sustainable synthetic routes to these compounds requires both innovation in strategy and capability. To address these challenges, chemists in the pharmaceutical sector have applied the concept of disruptive innovation [90], innovation that delivers a step change in the efficiency of preparing a molecule, in their approach to route development. Thus, the discovery, development, and rapid application of new synthetic methodologies, such as the reductive Heck reaction, can significantly enhance chemists’ capability to prepare novel drug candidates.

As previously mentioned, Larock’s seminal work laid the groundwork for the application of the reductive Heck to rapid generation of heterocycles [43]. In the years following Larock’s report, the asymmetric synthesis of dihydrobenzofurans [47], indanones [48–50], oxindoles [51], quaternary indolines [52, 53], and tetrahydropyridines [54], has been reported (Figure 4). All of these cores have been important substructures in the development of new drug candidates. 3-Arylindanones were reported to have anticancer activity [91], and as of 2017, six different oxindole core structures were in clinical trials for over fifteen different indications [92]. Hence, the development of new methods for applying a reductive Heck-like process to these heterocyclic systems, could have a significant impact on the development of commercially viable routes to many different clinical candidates.

While the intermolecular reductive Heck has seen some limited usage in the pharmaceutical industry (synthesis of NK-1 receptor antagonist precursors, Figure 6A [84]) and drug discovery [93–100], the continued development of reductive Heck reactions on terminal and unactivated alkenes represents a valuable new disconnection in medicinal chemistry. The formation of an C(sp2)–C(sp3) bond between simple aromatic halides and terminal alkenes affords functionalized intermediates from simple, commercially available, inexpensive reagents [87], and has the potential to replace Negishi and Suzuki couplings as the preferred disconnection for these advanced intermediates. Further, the reductive Heck reaction of unactivated alkenes with aryl bromides has been reported in good yield and moderate to good selectivity [41], suggesting that the vast array of aryl bromides will soon be suitable partners in a reductive Heck transformation.

Whether it is in heterocycle formation, synthesis of an early intermediate from two commercially available chemicals, or a late-stage application in a convergent synthesis, there is potential for the reductive Heck to impact several different areas of route development. Building upon the knowledge gained from these early studies along with an increased mechanistic understanding of the metal center will continue to enable advances in this field, which in turn will lead to the development of new methodologies and increased applications in pharmaceutical development.

Concluding Remarks.

Despite its appeal in organic synthesis, the palladium-catalyzed reductive Heck reaction represents a largely unexplored area of chemical reactivity—particularly when viewed in comparison to the classical Mizoroki–Heck coupling. The development of generally applicable intermolecular protocols and the discovery of asymmetric intramolecular systems are key milestones during the past two decades that foreshadow further breakthroughs in the near future. Considering the potential impact of new discoveries in this area on the practice of complex molecules synthesis in academia and in the pharmaceutical industry, new insights that address outstanding questions—some of which we have highlighted—are expected to find immediate application in basic research and translational science (see Outstanding Questions). Additionally, a deeper understanding of the reaction mechanisms of known and newly discovered reductive Heck reactions would aid these endeavors by offering a firm platform for systematic and hypothesis-driven work on this topic.

Acknowledgements.

Financial support for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health (5R35GM125052-02), the National Science Foundation (Graduate Research Fellowships to L.J.O. and J.A.G.: NSF/ DGE-184247, NSF/ DGE-1346837), and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Glossary.

- Alkylpalladium(II) intermediate

An intermediate σ-alkylpalladium species formed following carbopalladation/migratory insertion that is susceptible to further functionalization or β-hydride elimination

- β-hydride elimination

Process by which an M–C(sp3) and C–H bond are cleaved to form an M–H and C=C bond (microscopic reverse of migratory insertion)

- Enantiomeric excess (ee)

The degree to which one enantiomer is in excess to the other (a measure of optical purity)

- Hydroarylation

Any reaction by which a hydrogen atom and aryl group are added across a π-system

- Migratory insertion

The insertion of a π-system into an M–X bond to form two new σ-bonds (microscopic reverse of β-hydride elimination)

- Protonolysis

Acid-mediated cleavage of a bond following protonation, commonly invoked in organometallic mechanisms (cleavage of M–R bonds)

- Oxidative addition

Process by which substrate addition increases the coordination number and oxidation state of a metal center (microscopic reverse of reductive elimination)

- Reductive elimination

Process by which expulsion of a substrate decreases the coordination number and oxidation state of a metal center (microscopic reverse of oxidative addition)

- Syn-periplanar

A stereochemical arrangement in which the two groups of interest have a dihedral angle between 30° and −30° (on the same face/plane of a bond)

- Tetraalkylammonium salts

Common additives in Heck reactions run under “Jeffrey conditions,” in which the tetraalkylammonium salts are commonly proposed to act as phase transfer catalysts

- Triflate/nonaflate

Common names for trifluoromethanesulfonate and nonafluorobutanesulfonate, respectively, which serve as good leaving groups in organic reactions

References:

- 1.Fujiwara Y et al. (1969) Aromatic Substitution of Olefins. VI. Arylation of Olefins with Palladium(II) Acetate. J. Am. Chem. Soc 91, 7166–7169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizoroki T et al. (1971) Arylation of Olefin with Aryl Iodide Catalyzed by Palladium. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 44, 581 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heck RF and Nolley JP (1972) Palladium-Catalyzed Vinylic Hydrogen Substitution Reactions with Aryl, Benzyl, and Styryl Halides. J. Org. Chem 37, 2320–2322 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heck RF (1979) Palladium-Catalyzed Reactions of Organic Halides with Olefins. Acc. Chem. Res 12, 146–151 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cabri W and Candiani I (1995) Recent Developments and New Perspectives in the Heck Reaction. Acc. Chem. Res 28, 2–7 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beletskaya IP and Cheprakov AV (2000) The Heck Reaction as a Sharpening Stone of Palladium Catalysis. Chem. Rev 100, 3009–3066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dounay AB and Overman LE (2003) The Asymmetric Intramolecular Heck Reaction in Natural Product Total Synthesis. Chem. Rev 103, 2945–2963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cartney DM and Guiry PJ (2011) The asymmetric Heck and related reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev 40, 5122–5150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colacot TJ et al. (2012) Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling: A Historical Contextual Perspective to the 2010 Nobel Prize. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 51, 5062–5085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rauf W and Brown JM (2013) Reactive intermediates in catalytic alkenylation; pathways for Mizoroki–Heck, oxidative Heck and Fujiwara–Moritani reactions. Chem. Commun 49, 8430–8440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friis SD et al. (2016) Asymmetric Hydroarylation of Vinylarenes Using a Synergistic Combination of CuH and Pd Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 8372–8375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friis SD et al. (2017) A Dual Palladium and Copper Hydride Catalyzed Approach for Alkyl– Aryl Cross-Coupling of Aryl Halides and Olefins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 56, 7242–7246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coombs JR and Morken JP (2016) Catalytic Enantioselective Functionalization of Unactivated Terminal Alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 55, 2636–2649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crossley SWM et al. (2016) Mn‐, Fe‐, and Co-Catalyzed Radical Hydrofunctionalizations of Olefins. Chem. Rev 116, 8912–9000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen J et al. (2019) Nickel-catalyzed anti-Markovnikov hydroarylation of alkenes. Chem. Sci 10, 3231–3236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y-G et al. (2019) Nickel-catalyzed Enantioselective Hydroarylation and Hydroalkenylation of Styrenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 141, 3395–3399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald RI et al. (2011) Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Alkene Functionalization via Nucleopalladation: Stereochemical Pathways and Enantioselective Catalytic Applications. Chem. Rev 111, 2981–3019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mei T-S et al. (2013) Enantioselective Redox-Relay Oxidative Heck Arylations of Acyclic Alkenyl Alcohols using Boronic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 135, 6830–6833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang C et al. (2015) Enantioselective Dehydrogenative Heck Arylations of Trisubstituted Alkenes with Indoles to Construct Quaternary Stereocenters [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Mei T-S et al. (2014) Enantioselective construction of remote quaternary stereocenters. Nature 508, 340–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kürti L and Czakó B (2005) Strategic Applications of Named Reactions in Organic Synthesis: Background and Detailed Mechanisms, Elsevier Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cacchi S (1990) The palladium-catalyzed hydroarylation and hydrovinylation of carbon-carbon multiple bonds: new perspectives in organic synthesis. Pure & Appl. Chem 62, 713–722 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Catellani M et al. (1980) New transition metal-catalyzed C–C coupling reactions initiated by C–X bond cleavage and terminated by H-transfer. J. Organomet. Chem 199, 21–23 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arcadi A et al. (1989) Palladium-catalyzed preparation of exo-aryl derivatives of the norbornane skeleton. J. Organomet. Chem 368, 249–256 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunner H and Kramler K (1991) Asymmetric Catalysis. 72.1 Enantioselective Hydroarylation of Norborene and Norboradiene with Palladium(II) Acetate/Phosphine Catalysts. Synthesis 12, 1121–1124 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakuraba S et al. (1994) Asymmetric Heck-type hydroarylation of norbornene with phenyl triflate catalyzed by palladium complexes of chiral (β-N-sulfonylaminoalkyl)phosphines. Synlett 4, 291–292 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Namyslo JC and Kaufmann DE (1997) Palladium-catalyzed enantioselective hydrophenylation and hydroheterarylation of bicyclo[2.2.1]hept-2-ene: influence of the chiral ligand, the leaving group, and the solvent. Chem. Ber. Recl, 130, 1327–1331 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu X-Y, et al. (2000) Enantioselective Heck-type hydroarylation of norbornene with phenyl iodide catalyzed by palladium/quinolinyl-oxazolines. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 11, 1255–1257 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dupont J et al. (2001) A palladium complex containing a new C2-symmetric bidentate non-racemic oxalamidine ligand: synthesis and catalytic properties. Inorg. Chem. Commun 4, 471–474 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu X-Y, et al. (2001) Asymmetric hydroarylation of norbornene derivatives catalyzed by palladium complexes of chiral quinolinyl-oxazolines. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 12, 2565–2569 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drago D and Pregosin PS (2002) Palladium-Duphos Structural and Enantioselective Hydroarylation Chemistry. Organometallics 2002, 21, 1208–1215 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Namyslo JC et al. (2010) The hydroarylation reaction—scope and limitations. Molecules, 15, 3402–3410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozawa F et al. (1994) Palladium-catalysed Asymmetric Hydroalkenylation of Norbornene. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 11, 1323–1324 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moinet C and Fiaud J-C (1995) Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrophenylation of 1,4-dihydro-1,4-epoxynapthalene. Tetrahedron Lett 36, 2051–2052 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Namyslo JC and Kaufmann DE (1999) Asymmetric Synthesis of Both Enantiomers of N-Protected Epibatidine via Reductive Heck-Type Hetarylation. Synlett 6, 804–806 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X-G et al. (2003) Asymmetric Hydroarylation of hetero-atom containing norborene derivatives and enantioselective synthesis of analogs of epibatidine. Arkivoc 2, 15–20 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kasyan A et al. (1998) Regiochemistry of the Reductive Heck Coupling of 2-Azabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene. Synthesis of Epibatidine Analogues. Tetrahedron 54, 9047–8054 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox CD and Malpass JR (1999) Synthesis of Epibatidine Isomers: Reductive Heck Coupling of 2-Azabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene derivatives. Tetrahedron 55, 11879–11888 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jana GK and Sinha S (2012) Reductive Heck coupling: an efficient approach toward the iboga alkaloids. Synthesis of ibogamine, epiibogamine and iboga analogs. Tetrahedron Lett 53, 1671–1674 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torri S et al. (1985) Pd(0)-catalyzed electro-reductive hydrocoupling of aryl halides with olefins and acetylenes. Chem. Lett 14, 1353–1354 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin L et al. (2018) Pd-Catalyzed reductive heck reaction of olefins with aryl bromides for Csp2–Csp3 bond formation. Chem. Commun 54, 5752–5755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saini V et al. (2015) Synthesis of Highly Functionalized Tri- and Tetrasubstituted Alkenes via Pd-Catalyzed 1,2-Hydrovinylation of Terminal 1,3-Dienes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 608–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larock RC and Babu S (1987) Synthesis of nitrogen heterocycles via palladium-catalyzed intramolecular cyclization. Tetrahedron Lett 28, 5291–5294 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abdel-Magid AF (2017) Viral Replication Inhibitors May Treat the Dengue Virus Infections. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 8, 14–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li M-H et al. , Indoline compounds for tracing histone acetylation inhibitors pet imaging for diagnosis and treatment of tumors Patent US2018/0099933

- 46.Diaz P et al. (1998) New Synthetic Retinoids Obtained by Palladium-Catalyzed Tandem Cyclisation-Hydride Capture Process. Tetrahedron 54, 4579–4590 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Z-M et al. (2018) Palladium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Reductive Heck Reactions: Convenient Access to 3,3-Disubstituted 2,3-Dihydrobenzofuran. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 57, 10373–10377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minatti A et al. (2007) Synthesis of Chiral 3-Substituted Indanones via an Enantioselective Reductive-Heck Reaction. J. Org. Chem 72, 9253–9258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yue G et al. (2015) Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Heck Reaction of Aryl Halides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 54, 6531–6535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mannathan S et al. (2017) Enantioselective Intramolecular Reductive Heck Reaction with a Palladium/Monodentate Phosphoramidite Catalyst. ChemCatChem 9, 551–554 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kong W et al. (2017) Water as a Hydride Source in Palladium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Reductive Heck Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 56, 3987–3991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shen C (2015) Enantioselective Arylative Dearomatization of Indoles via Pd-Catalyzed Intramolecular Reductive Heck Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 4936–4939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liang R-X et al. (2018) Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric dearomative alkenylation of indoles through a reductive-Heck reaction. Org. Chem. Front 5, 1840–1843 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hou L et al. (2017) Pd(0)-Catalysed asymmetric reductive Heck-type cyclization of (Z)-1-iodo-1,6-dienes and enantioselective synthesis of quaternary tetrahydropyridines. Org. Biomol. Chem 15, 4803–4806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yuan Z et al. 2019) Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Intramolecular Reductive Heck Desymmetrization of Cyclopentenes: Access to Chiral Bicyclo-[3.2.1]octanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 58, 2884–2888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu P et al. (2019) Quaternary-centre-guided synthesis of complex polycyclic terpenes. Nature DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1179-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trost BM and Toste FD (1999) Palladium-Catalyzed Kinetic and Dynamic Kinetic Asymmetric Transformation of 5-Acyloxy-2-(5H)-furanone. Enantioselective Synthesis of (−)-Aflatoxin B Lactone. J. Am. Chem. Soc 121, 3543–3544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee K and Cha JK (2001) Formal Synthesis of (+)-Phorbol. J. Am. Chem. Soc 123, 5590–5591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trost BM et al. (2002) DYKAT of Baylis-Hillman Adducts: Concise Total Synthesis of Furaquinocin E. J. Am. Chem. Soc 124, 11616–11617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ichikawa M et al. (2004) Total Synthesis of (−)-Incarvilline, (+)-Incarvine C, and (−)-Incarvillateine. J. Am. Chem. Soc 126, 16553–16558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dounay AB et al. (2008) Total Synthesis of the Strychnos Alkaloid (+)-Minfiensine: Tandem Enantioselective Intramolecular Heck-Iminium Ion Cyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 130, 5368–5377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gao P and Cook SP A Reductive-Heck Approach to the Hydroazulene Ring System: A Formal Synthesis of the Englerins. Org. Lett 14, 3340–3343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen J-Q et al. (2012) Total Synthesis of (–)-Galanthamine and (–)-Lycoramine via Catalytic Asymmetric Hydrogenation and Intramolecular Reductive Heck Cyclization. Org. Lett 14, 2714–2717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baran PS et al. (2007) Total synthesis of marine natural products without using protecting groups. Nature 446, 404–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maimone TJ et al. (2015) Scalable total syntheses of (–)-hapalindole U and (+)-ambiguine H. Tetrahedron 71, 3652–3665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Diethelm S and Carreira EM (2013) Total Synthesis of (±)-Gelsemoxonine. J. Am. Chem. Soc 135, 8500–8503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cacchi S and Arcadi A (1983) Catalyzed Conjugate Addition Type Reaction of Aryl Iodides with α,β-Unsaturated Ketones. J. Org. Chem 48, 4236–4240 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cacchi S and Palmieri G (1984) A One-Pot Palladium-Catalyzed Synthesis of β,β-Diarylketones and Aldehydes from Aryl Iodides and α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyl Compounds. Synthesis, 7, 575–577 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cacchi S and Palmieri G (1985) The palladium-catalyzed conjugate addition type reaction of 2-bromo-arylmercury compounds and 2-bromo-aryl iodides with α,β-enones: A new entry to 1-indanols. J. Organomet. Chem 282, 3–6 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cacchi S (1984) The palladium-catalyzed conjugate addition type reaction of aryl iodides with α,β-unsaturated ketones. J. Organomet. Chem 286, 48–51 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arcadi A et al. (1986) The reaction of aryl iodides with hindered α,β,γ,δ-dienones in the presence of the [Pd(OAc)2(PPh3)2]-trialkylammonium formate reagent. J. Organomet. Chem 312, 27–32 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Amorese A et al. (1989) Conjugate addition vs. vinylic substitution in palladium-catalysed reaction of aryl halides with β-substituted-α,β-enones and -enals. Tetrahedron 45, 813–828 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arcadi A et al. (1991) Palladium-Catalyzed Conjugate Reduction of α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyl Compounds with Potassium Formate. Synlett 1, 27–28 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Raoufmoghaddam S et al. (2015) Palladium(0)/NHC-Catalyzed Reductive Heck Reaction of Enones: A Detailed Mechanistic Study. Chem. Eur. J 21, 18811–18820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Raoufmoghaddam S et al. (2018) Importance of the Reducing Agent in Direct Reductive Heck Reactions. ChemCatChem 10, 266–272 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mannathan S et al. (2015) Palladium(II) Acetate Catalyzed Reductive Heck Reaction of Enones; A Practical Approach. ChemCatChem 7, 3923–3927 [Google Scholar]

- 77.McCrindle R et al. (1983) Reaction of Tertiary Amines with Bis(benzonitrile)dichloro-palladium(II). Formation and Crystal Structure Analysis of Di-μ-chloro-dichlorobis[2-(N,N-di-isopropyliminio)ethyl-C]dipalladium(II). J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 10, 571–572 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grushin VV and Alper H (1993) Alkali-Induced Disproportionation of Palladium(II) Tertiary Phosphine Complexes, [L2PdCl2], to LO and Palladium(0). Key Intermediates in the Biphasic Carbonylation of ArX Catalyzed by [L2PdCl2]. Organometallics 12, 1890–1901 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Trzeciak AM et al. (2002) Synthesis of Palladium Benzyl Complexes from the Reaction of PdCl2[P(OPh)3]2 with Benzyl Bromide and Triethylamine: Important Intermediates in Catalytic Carbonylation. Organometallics 21, 132–137 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lu CC and Peters JC (2004) Synthetic, Structural, and Mechanistic Aspects of an Amine Activation Process Mediated at a Zwitterionic Pd(II) Center. J. Am. Chem. Soc 126, 15818–15832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Amatore C et al. (2014) Kinetic Data on the Synergetic Role of Amines and Water in the Reduction of Phosphine-Ligated Palladium(II) to Palladium(0). Eur. J. Org. Chem 22, 4709–4713 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gottumukkala AL et al. (2011) Pd–NHC Catalyzed Conjugate Addition versus the Mizoroki–Heck Reaction. Chem. Eur. J 17, 3091–3095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Parveen N et al. (2017) Stable and Reusable Palladium Nanoparticles-Catalyzed Conjugate Addition of Aryl Iodides to Enones: Route to Reductive Heck Products. Adv. Synth. Catal 359, 3741–3751 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kulagowski JJ et al. (2001) Stereocontrolled Syntheses of Epimeric 3-Aryl-6-phenyl-1-oxa-7-azaspiro[4.5]decane NK-1 Receptor Antagonist Precursors. Org. Lett 3, 667–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Merlic CA and Semmelhack MF (1990) An interesting chloride ion effect in the Heck reaction. J. Organomet. Chem 391, 23–27 [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gurak JA and Engle KM (2018) Practical Intermolecular Hydroarylation of Diverse Alkenes via Reductive Heck Coupling. ACS Catal 8, 8987–8992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang C et al. (2018) Palladium-Catalyzed Regiocontrollable Reductive Heck Reaction of Unactivated Aliphatic Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 9332–9336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li J and Eastgate MD (2019) Making Better Decisions During Synthetic Route Design: Leveraging Prediction to Achieve Greenness-by-Design. React. Chem. Eng, Advance Article [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li J, Eastgate MD (2015) Current complexity: a tool for assessing the complexity of organic molecules. Org. Biomol. Chem 13, 7164–7176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eastgate MD et al. (2017) On the design of complex drug candidate syntheses in the pharmaceutical industry. Nat. Rev. Chem 1, 1–16 [Google Scholar]

- 91.Patil SA et al. (2017) Recent developments in biological activities of indanones. Eur. J. Med. Chem 138, 182–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kaur M et al. (2016) Oxindole: A chemical prism carrying plethora of therapeutic benefits. Eur. J. Med. Chem 123, 858–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stokker GE (1987) Palladium catalyzed stereospecific Michael arylation of 6-alkyl-5,6-dihydro-2H-pyran-2-ones. Tetrahedron Lett 28, 3179–3182 [Google Scholar]

- 94.Veenstra SJ et al. (1997) Studies on the active conformation of NK1 antagonist CGP 49823. Part 1. Synthesis of conformationally restricted analogs. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett 7, 347–350 [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tobrman T and Dvořák D (2004) ‘Reductive Heck reaction’ of 6-halopurines. Tetrahedron Lett 45, 273–276 [Google Scholar]

- 96.Göksu G et al. (2008) Hydroarylation of bicyclic, unsaturated dicarboximides: access to aryl-substituted, bridged perhydroisoindoles. Tetrahedron Lett 49, 2685–2688 [Google Scholar]

- 97.Li Z et al. (2008) 1,3-Diaxially Substituted trans-Decalins: Potential Nonsteroidal Human Progesterone Receptor Inhibitors. J. Org. Chem 73, 7764–7767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Goksu G et al. (2010) Reductive Heck Reactions of N-Methyl-substituted Tricyclic Imides. Molecules 15, 1302–1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gunkara OT (2013) Synthesis of new aryl(hetaryl)-substituted tandospirone analogues with potential anxiolytic activity via reductive Heck type hydroarylations. Chemical Papers 67, 643–649 [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sweeny JB et al. (2018) Synthesis of 3-substituted pyrrolidines via palladium-catalysed hydroarylation. iScience 9, 328–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]