Abstract

The cerebral cortex underlies our complex cognitive capabilities, yet little is known about the specific genetic loci that influence human cortical structure. To identify genetic variants that affect cortical structure, we conducted a genome-wide association meta-analysis of brain magnetic resonance imaging data from 51,665 individuals. We analyzed the surface area and average thickness of the whole cortex and 34 regions with known functional specializations. We identified 199 significant loci and found significant enrichment for loci influencing total surface area within regulatory elements that are active during prenatal cortical development, supporting the radial unit hypothesis. Loci that affect regional surface area cluster near genes in Wnt signaling pathways, which influence progenitor expansion and areal identity. Variation in cortical structure is genetically correlated with cognitive function, Parkinson’s disease, insomnia, depression, neuroticism, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

INTRODUCTION:

The cerebral cortex underlies our complex cognitive capabilities. Variations in human cortical surface area and thickness are associated with neurological, psychological, and behavioral traits and can be measured in vivo by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Studies in model organisms have identified genes that influence cortical structure, but little is known about common genetic variants that affect human cortical structure.

RATIONALE:

To identify genetic variants associated with human cortical structure at both global and regional levels, we conducted a genome-wide association meta-analysis of brain MRI data from 51,665 individuals across 60 cohorts. We analyzed the surface area and average thickness of the whole cortex and 34 cortical regions with known functional specializations.

RESULTS:

We identified 306 nominally genome-wide significant loci (P < 5 × 10−8) associated with cortical structure in a discovery sample of 33,992 participants of European ancestry. Of the 299 loci for which replication data were available, 241 loci influencing surface area and 14 influencing thickness remained significant after replication, with 199 loci passing multiple testing correction (P < 8.3 × 10−10; 187 influencing surface area and 12 influencing thickness). Common genetic variants explained 34% (SE = 3%) of the variation in total surface area and 26% (SE = 2%) in average thickness; surface area and thickness showed a negative genetic correlation (rG = −0.32, SE = 0.05, P = 6.5 × 10−12), which suggests that genetic influences have opposing effects on surface area and thickness. Bioinformatic analyses showed that total surface area is influenced by genetic variants that alter gene regulatory activity in neural progenitor cells during fetal development. By contrast, average thickness is influenced by active regulatory elements in adult brain samples, which may reflect processes that occur after mid-fetal development, such as myelination, branching, or pruning. When considered together, these results support the radial unit hypothesis that different developmental mechanisms promote surface area expansion and increases in thickness.

To identify specific genetic influences on individual cortical regions, we controlled for global measures (total surface area or average thickness) in the regional analyses. After multiple testing correction, we identified 175 loci that influence regional surface area and 10 that influence regional thickness. Loci that affect regional surface area cluster near genes involved in the Wnt signaling pathway, which is known to influence areal identity.

We observed significant positive genetic correlations and evidence of bidirectional causation of total surface area with both general cognitive functioning and educational attainment. We found additional positive genetic correlations between total surface area and Parkinson’s disease but did not find evidence of causation. Negative genetic correlations were evident between total surface area and insomnia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depressive symptoms, major depressive disorder, and neuroticism.

CONCLUSION:

This large-scale collaborative work enhances our understanding of the genetic architecture of the human cerebral cortex and its regional patterning. The highly polygenic architecture of the cortex suggests that distinct genes are involved in the development of specific cortical areas. Moreover, we find evidence that brain structure is a key phenotype along the causal pathway that leads from genetic variation to differences in general cognitive function.▪

Graphical abstract

Identifying genetic influences on human cortical structure. (A) Measurement of cortical surface area and thickness from MRI. (B) Genomic locations of common genetic variants that influence global and regional cortical structure. (C) Our results support the radial unit hypothesis that the expansion of cortical surface area is driven by proliferating neural progenitor cells. (D) Cortical surface area shows genetic correlation with psychiatric and cognitive traits. Error bars indicate SE.

The human cerebral cortex is the outer gray matter layer of the brain and is implicated in multiple aspects of higher cognitive function. Its distinctive folding pattern is characterized by convex (gyral) and concave (sulcal) regions. Computational brain mapping approaches use the consistent folding patterns across individual cortices to label brain regions (1). During fetal development, excitatory neurons—the predominant neuronal cell type in the cortex—are generated from neural progenitor cells in the developing germinal zone (2). The radial unit hypothesis (3) posits that the expansion of cortical surface area (SA) is driven by the proliferation of these neural progenitor cells, whereas thickness (TH) is determined by the number of their neurogenic divisions. Variation in global and regional measures of cortical SA and TH have been reliably associated with neuropsychiatric disorders and psychological traits (4) (table S1). Twin and family-based brain imaging studies indicate that SA and TH measurements are highly heritable and are influenced by largely different genetic factors (5–7). Despite extensive studies of genes affecting cortical structure in model organisms, our current understanding of the genetic variation affecting human cortical size and patterning is limited to rare, highly penetrant variants (8, 9). These variants often disrupt cortical development, leading to altered postnatal structure. However, little is known about how common genetic variants influence human cortical SA and TH.

To identify genetic loci associated with variation in the human cortex, we conducted genome-wide association meta-analyses of cortical SA and THmeasures in 51,665 individuals, primarily (~94%) of European descent, from60 cohorts fromaround the world (tables S2 to S4). Cortical measures were extracted from structural brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans in 34 regions defined by the commonly used Desikan-Killiany atlas, which establishes coarse partitions of the cortex. The regional boundaries are based on gyral anatomy labeled from between the depths of the sulci (10, 11). We analyzed two global measures, total SA and average TH, as well as SA and TH for the 34 regions averaged across both hemispheres, yielding 70 distinct phenotypes (Fig. 1A and table S1).

Fig. 1. Regions of the human cortex and associated genetic loci.

(A) The 34 cortical regions defined by the Desikan-Killiany atlas. (B) Ideogram of loci that influence cortical SA and TH.

Within each cohort, we used an additive model to conduct a genome-wide association study (GWAS) for each of the 70 phenotypes. To identify genetic influences specific to each region, the primary GWAS of regional measures included the global measure of SA or TH as a covariate. To estimate themultiple testing burden associated with analyzing 70 phenotypes, we used matrix spectral decomposition (12), which yielded 60 independent traits, and a multiple testing significance threshold of P ≤ 8.3 × 10−10.

The principal meta-analysis comprised results from 33,992 participants of European ancestry (23,909 from49 cohorts participating in the ENIGMA consortium and 10,083 from the UK Biobank). We sought replication for loci reaching genome-wide significance (P ≤ 5×10−8) in an additional ENIGMA cohort (777 participants) and the CHARGE consortium (13) (13,952 participants). In addition, wemeta-analyzed eight cohorts of non-European ancestry (2944 participants) to examine the generalization of these effects across ancestries. High genetic correlations were observed between the metaanalyzed ENIGMA European cohorts and the UK Biobank cohort using linkage disequilibrium(LD) score regression (total SA rG = 1.00, z-score PrG = 2.7 × 10−27; average THrG =0.91, z-score PrG = 1.7 × 10−19), indicating consistent genetic architecture between the 49 ENIGMA cohorts and data collected from a single scanner at the primary UK Biobank imaging site.

Across the 70 cortical phenotypes, we identified 306 loci that were genome-wide significant in the principal meta-analysis (P ≤ 5 × 10−8) (Fig. 1B and table S5). Of these, 118 have not been previously associated with either intracranial volume (ICV) or cortical SA, TH, or volume (13–18). Twenty of these loci were insertions or deletions (INDELs). Eleven INDELs had a proxy single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) available in the European replication data; no proxieswere available for six INDELs and one SNP. Of the 299 loci for which the SNP or a proxywas available, 255 (SA: 241, TH: 14) remained genome-wide significant when the replication data were included in themetaanalysis, with 199 passing multiple testing correction (P ≤ 8.3 × 10−10; SA: 187, TH: 12). Of the 255 loci, 244were available in the meta-analysis of non-European cohorts. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around the non-European metaanalysis effect sizes included those from the European meta-analysis for 241 of these loci. Of the 244 loci available in the non-European cohorts, 189 had effects in the same direction in both the European and non-European meta-analyses, and 111 became more significant when the whole sample was metaanalyzed (table S5 and fig. S1). Variability in effects across ancestrymay be due to differences in allele frequency; however, the power for these comparisons is limited, and further comparisons with larger non-European cohorts will help clarify the generalizability of these effects (table S5). We examined gene-based effects (allowing for a 50-kb window around genes) and found significant associations for 253 genes across the 70 cortical phenotypes (table S6). The meta-analytic results are summarized as Manhattan, QQ, Forest, and LocusZoom plots (figs. S2 to S5).

Genetics of total SA and average TH

Common variants explained 34% (SE = 3%) of the variation in total SA and 26% (SE = 2%) in average TH. These estimates account for more than a third of the heritability estimated from the Queensland Twin Imaging cohort (91% for total SA and 64% for average TH) (table S7), indicating thatmore genetic variants, including rare variants, are yet to be identified. To examine the extent to which our results could predict SA and TH, we derived polygenic risk scores (PRSs) fromthe principal meta-analysis results. These scores significantly predicted SA and TH in an independent sample of 5095 European participants, explaining between 2 and 3% of the trait variance (given a PRS threshold of P ≤ 0.01 R2 SA = 0.029, linear regression coefficient t test P = 6.54 × 10−50; R2 TH = 0.022, t test P = 3.34 × 10−33) (table S8).

We observed a significant negative genetic correlation between total SA and average TH (rG = −0.32, SE = 0.05, z-score PrG=6.5 × 10−12) (Fig. 2A), which persisted after exclusion of the chromosome 17 inversion region known to influence brain size (14) (rG = −0.31, SE = 0.05, z-score PrG = 3.3 × 10−12). Genetic correlations could indicate causal relationships between traits, pleiotropy, or a genetic mediator influencing both traits. Latent causal variable (LCV) analysis, which tests for causality using genome-wide data (19), showed no evidence of causation [LCV genetic causality proportion (gcp) = 0.06, t test Pgcp=0=0.729].The negative correlation suggests that genetic influences have opposing effects on SA and TH, which may result from pleiotropic effects or genetic effects on a mediating trait that, for example, might constrain total cortical volume. The absence of causality and the small magnitude of this correlation are consistent with the radial unit hypothesis (3), whereby different developmental mechanisms promote SA expansion and increases in TH.

Fig. 2. Genetics of global measures.

(A) Genetic correlations between global measures and selected traits (red indicates significant correlation, FDR < 0.05). Error bars indicate SE. (B) Partitioned heritability enrichment in active regulatory elements across tissues and cell types. ESC, embryonic stem cells; iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cells; ES–deriv, embryonic stem derived; HSC, hematopoietic stem cells; Mesench, mesenchymal; Myosat, myosatellite; Neurosph, neurosphere; Sm. Muscle, smooth muscle. (C) Partitioned heritability enrichment in temporally specific active regulatory elements. (D) Partitioned heritability enrichment in regulatory elements of cell type–specific genes in the fetal brain. (E) Manhattan plot of loci associated with total SA (top) and average TH (bottom). Green diamonds indicate lead SNPs in the principal meta-analysis, black diamonds indicate changes in P value after replication, dashed horizontal lines denote genome-wide significance, and solid horizontal lines represent the multiple testing correction threshold.

As expected, total SA showed a positive genetic correlation with ICV. This correlation remained after controlling for height, which demonstrates that this relationship is not solely driven by body size (Fig. 2A and table S8). The global cortical measures did not show significant genetic correlations with the volumes of major subcortical structures (Fig. 2A). The genetic correlation between total SA and the hippocampus is consistent with their shared telencephalic developmental origin.

To identify whether common variation associated with cortical structure relates to gene regulation within a given tissue type, developmental time period, or cell type, we performed partitioned heritability analyses (20) using sets of gene regulatory annotations from adult and fetal brain tissues (21, 22). Total SA and average TH showed the strongest enrichment of heritability within genomic regions of active gene regulation (promoters and enhancers) in brain tissue and in vitro neural models derived from stem cell differentiation (Fig. 2B and fig. S6A). To examine temporally specific regulatory elements, we selected active regulatory elements that are specifically present in either the mid-fetal brain or the adult cortex. Total SA showed significant enrichment of heritability only within mid-fetal–specific active regulatory elements, whereas average TH showed significant enrichment only within adult-specific active regulatory elements (Fig. 2C and fig. S6B). Stronger enrichment was found in regions of the fetal cortex with more accessible chromatin in the neural progenitor–enriched germinal zone than in the neuron-enriched cortical plate (fig. S6C), similar to a previous analysis for ICV (21). We then performed an additional partitioned heritability enrichment analysis using regulatory elements associated with cell type–specific gene expression derived from a large single-cell RNA sequencing study of the human fetal brain (23). This analysis revealed significant enrichment of total SA heritability in all progenitor cell types, including those in active phases of mitosis as well as three different classes of progenitor cells, including outer radial glia cells, a cell type associated with expansion of cortical SA in human evolution (2) (Fig. 2D and fig. S6D). We also identified significant enrichments in upper layer excitatory neurons, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, and microglia. These findings suggest that total SA is influenced by common genetic variants that may alter gene regulatory activity in neural progenitor cells during fetal development, supporting the radial unit hypothesis (3). By contrast, the strongest evidence of enrichment for average TH was found in active regulatory elements in the adult brain samples, which may reflect processes that occur after mid-fetal development, such as myelination, branching, or pruning (24).

We conducted pathway analyses to determine whether there was enrichment of association near genes in known biological pathways (25). We found 91 significant gene sets for total SA and 4 significant sets for average TH (table S9). Gene sets associated with total SA included chromatin binding, a process that guides neurodevelopmental fate decisions (26) (table S9 and fig. S7A). In addition, consistent with the partitioned heritability analyses implicating neural progenitor cells in total SA, gene ontology terms relevant to the cell cycle also showed significant enrichment in these analyses.

Loci influencing total SA and average TH

Seventeen of the 255 replicated loci were associated with total SA; 12 survived correction for multiple testing (Fig. 2E and table S5). Eight loci influencing total SA have been previously associated with ICV (14). These include rs79600142 (principal meta-analysis PMA=2.3 × 10−32; replication Prep=3.5 × 10−43; P values reported from all meta-analytic results were for z-scores from fixed-effectmetaanalyses) in the highly pleiotropic chromosome 17q21.31 inversion region, which has been associated with Parkinson’s disease (27), educational attainment (28), and neuroticism(29). On 10q24.33, rs1628768 (z-score PMA = 1.7×10−13; Prep = 1.0 × 10−17) was shown by our bioinformatic annotations (30) to be an expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) that influences expression levels of the INA gene and the schizophrenia candidate genes (31) AS3MT, NT5C2, andWBP1L [linear regression coefficient t test false discovery rate (FDR)– corrected P value for the association of rs1628768 with expression data from surrounding genes FDRCommonMindConsortium(CMC) < 1.0 × 10−2] (tables S11 and S12). This regionhas been associated with schizophrenia; however, rs1628768 is in low LD with the schizophreniaassociated SNP rs11191419 (r2 = 0.15) (32). The 6q21 locus influencing total SA is intronic to FOXO3 (which also showed a significant genebased association with total SA) (table S6). The major allele of the lead variant rs2802295 is associated with larger total SA (z-score PMA = 2.5 × 10−10; Prep = 2.5 × 10−13) and is in complete LD with rs2490272, a SNP previously associated with higher general cognitive function (33).

One locus not previously associated with ICV is rs11171739 (z-score PMA = 8.4 × 10−10; Prep = 8.1 × 10−11) on 12q13.2. This SNP is in high LD with SNPs associated with educational attainment (28) and is an eQTL for RPS26 in the fetal (34) and adult cortex (30) [t test of Pearson’s r FDRFETAL = 2.0 × 10−24, empirical t test of Pearson’s r FDRGenotype-Tissue Expression(GTEx) = 3.3 × 10−40] (tables S11 and S12). On 3p24.1, rs12630663 (z-score PMA = 1.3 × 10−8; Prep = 1.4 × 10−8) is of interest because of its proximity (~200 kb) to EOMES (also known as TBR2), which is expressed specifically in intermediate progenitor cells in the developing fetal cortex (35). rs12630663 is located in a chromosomal region with chromatin accessibility specific to the germinal zone in the human fetal cortex (21). Putatively causal SNPs in this region (table S13) show significant chromatin interactions with the EOMES promoter (36). The region also contains many regulatory elements that, when excised via CRISPR-Cas9 in differentiating neural progenitor cells, significantly reduced EOMES expression (21). A rare homozygous chromosomal translocation in the region separating the regulatory elements from EOMES (fig. S8) silences EOMES expression and causes microcephaly (37), demonstrating that rare and common noncoding variation can have similar phenotypic consequences but to different degrees.

The two replicated loci associated with average TH, neither of which have been previously identified,survivedcorrection for multipletesting (Fig. 2E and table S5). On 3p22.1, rs533577 (z-score PMA = 8.4 × 10−11; Prep = 3.7 × 10−12) is a fetal cortex eQTL (t test FDRFETAL = 1.8 × 10−4) for RPSA, encoding a 40S ribosomal protein with a potential role as a laminin receptor (38). Laminins are major constituents of the extracellular matrix and have critical roles in neurogenesis, neuronal differentiation, and migration (39). On 2q11.2, rs11692435 (z-score PMA = 3.2 × 10−10; Prep = 4.5 × 10−10) encodes a missense variant (p.A143V) predicted to affect ACTR1B protein function (40) and is an ACTR1B eQTL in the fetal cortex (ttest FDRFETAL = 3.9 × 10−2) (tables S11 and S12). ACTR1B is a subunit of the dynactin complex involved in microtubule remodeling, which is important for neuronal migration (41).

Genetics of regional SA and TH

The amount of phenotypic variance explained by common variants was higher for SA (8 to 31%) than TH (1 to 13%) for each of the specific cortical regions (Fig. 3, A and B, and table S7). To focus on region-specific influences, we controlled for global measures in the regional GWAS, which reduced the covariance between the regional measures (tables S14 and S15). Similar to the genetic correlation between global SA and TH, when significant, genetic correlations between regional SA and TH within the same region were moderate and negative (tables S14 and S15). This suggests that genetic variants that contribute to the expansion of SA in a specific region tend to also contribute to thinner TH in that region.

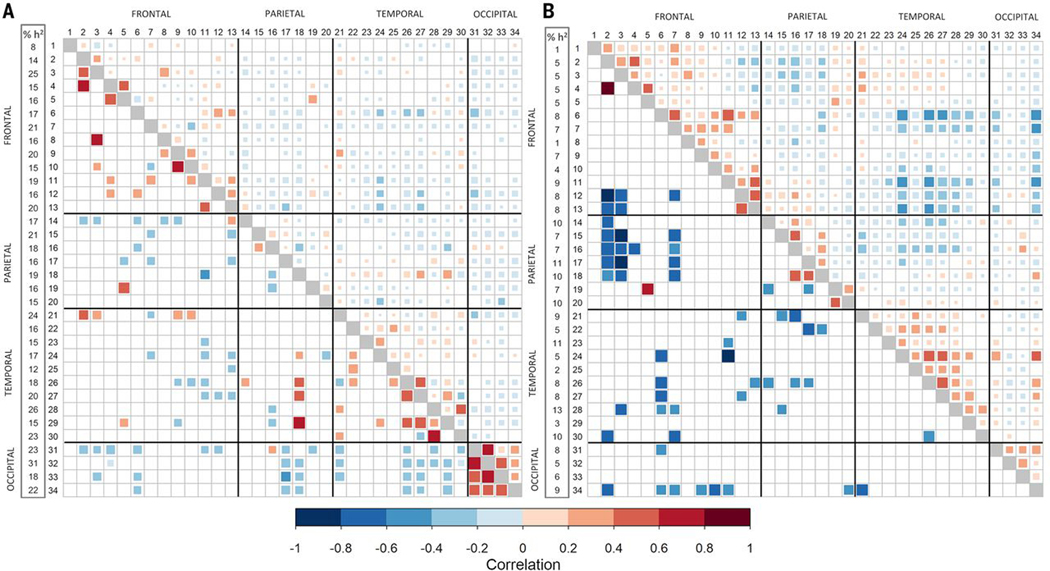

Fig. 3. Genetic and phenotypic correlations between cortical regions.

(A) Surface area. (B) Thickness. Regions are numbered according to the inset key of Fig. 1A. The proportion of variance accounted for by common genetic variants is shown in the first column (h2SNP). Phenotypic correlations from the UK Biobank are in the upper right triangle. Genetic correlations from the principal meta-analysis are in the lower left triangle. Only significant correlations are shown.

Genetic correlations between regions were calculated separately for SA and TH. Most genetic correlations between regions did not survive multiple testing correction. For SA, significant positive genetic correlations were generally found between physically adjacent regions and negative correlations between more distal regions (Fig. 3A). This pattern mirrored the phenotypic correlations between regions and was also observed for TH (Fig. 3, A and B). Consistent with this finding, hierarchical clustering of the genetic correlations resulted in a general grouping by physical proximity (fig. S9). These positive genetic correlations were strongest between SA of regions surrounding the major, early-forming sulci (e.g., the pericalcarine, lingual, cuneus, and lateral occipital regions surrounding the calcarine sulcus), which may reflect genetic effects acting on the development of the sulci (11).

To further investigate biological pathways that influence areal (regional) identity, we used multivariate GWAS analyses (42) to aggregate association statistics separately for regional SA and TH. These analyses identify variants shared across regions and those within specific regions while accounting for the phenotypic correlations between regions. Pathway analyses of the multivariate SA results showed significant enrichment for 903 gene sets (table S10), many of which are involved in Wnt signaling, with the canonical Wnt signaling pathway showing the strongest enrichment (z-score, P = 8.8 × 10−11). Wnt proteins regulate neural progenitor fate decisions (43, 44) and are expressed in spatially specific manners that influence areal identity (45). Pathway analyses of the multivariate TH results did not yield any findings that survived multiple testing correction.

Loci influencing regional SA and TH

A total of 224 loci were nominally associated with regional SA and 12 with regional TH; of these, 175 SA and 10 TH loci survived multiple testing correction (table S5). As shown in Fig. 1B, most loci were associated with a single cortical region. Of the loci influencing regional measures, a few were also associated with global measures. Those that were associated showed effects in the same direction, indicating that the significant regional loci were not due to collider bias (46) (fig. S10).

The strongest regional association was observed on chromosome 15q14 with the precentral SA (rs1080066, z-score PMA = 1.8 × 10−137; Prep = 4.6 × 10−189; variance explained = 1.03%) (Fig. 4A). Across 11 traits, we observed 41 independent significant associations from 18 LD blocks (r2 threshold ≤ 0.02) (Fig. 4B and table S5). As we observed strong association with the SA of both pre-and post-central gyri (Fig. 4C), we localized the association within the central sulcus in 5993 unrelated individuals from the UK Biobank. The most significant association between rs1080066 and sulcal depth was observed around the pli de passage fronto-pariétal moyen (linear regression coefficient t test P = 7.9 × 10−21), a region associated with hand fine-motor function in humans (47), which shows distinctive depth patterns across different species of primates (48) (Fig. 4D). rs1080066 is a fetal cortex eQTL for a downstream gene, EIF2AK4 (t test FDRFETAL = 4.8 × 10−2), that encodes the GCN2 protein, which is a negative regulator of synaptic plasticity, memory, and neuritogenesis (49). The functional data also highlight THBS1 via chromatin interaction between the rs1080066 region and the promoter in neural progenitor cells and an eQTL effect in whole blood (z-score FDRBIOSgenelevel = 6.1 × 10−6). THBS1 has roles in synaptogenesis and the maintenance of synaptic integrity (50).

Fig. 4. Genetics of regional measures.

(A) Regional plot for rs1080066, including additional lead SNPs within the LD block and surrounding genes, chromatin interactions in neural progenitor cells, chromatin state in RoadMap brain tissues, and BRAINSPAN candidate gene expression in brain tissue. (B) Ideogram of 15q14, detailing the significant independent loci and cortical regions. (C) rs1080066 (G allele) association with SA of regions. (D) rs1080066 association with central sulcus depth and depth of several primate species. RoadMap chromatin states: TssA, active transcription start site (TSS); TssAFlnk, flanking active TSS; TxFlnk, transcription at gene 5′ and 3′; Tx, strong transcription; TxWk, weak transcription; EnhG, genic enhancers; Enh, enhancers; Het, heterochromatin; TssBiv, bivalent/poised TSS; BivFlnk, flanking bivalent TSS/enhancer; EnhBiv, bivalent enhancer; ReprPC, repressed Polycomb; ReprPCWk, weak repressed Polycomb; Quies, quiescent/low. BRAINSPAN cortical tissue types: DFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; VFC, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex; MFC, anterior cingulate cortex; OFC, orbital frontal cortex; M1C, primary motor cortex; M1C-S1C, primary motor-sensory cortex; PCx, parietal neocortex; S1C, primary somatosensory cortex; IPC, posteroventral parietal cortex; A1C, primary auditory cortex;TCx, temporal neocortex; STC, posterior superior temporal cortex; ITC, inferolateral temporal cortex; Ocx, occipital neocortex; V1C, primary visual cortex.

Consistent with enrichment in the pathway analyses, many other loci were located in regions with functional links to genes involved in Wnt signaling (fig. S7B), including 1p13.2, where rs2999158 (lingual SA, z-score PMA = 1.9 × 10−11, Prep = 3.0 × 10−11; pericalcarine SA, z-score PMA = 1.9 × 10−11; Prep = 9.9 × 10−16) is an eQTL for ST7L and WNT2B (t test FDRCMC < 1.0 × 10−2) in the adult cortex (tables S11 and S12). On 14q23.1, we observed 20 significant loci (table S5) from four LD blocks. The strongest association here was for the precuneus SA (rs73313052: z-score PMA = 1.1 × 10−24; Prep = 2.2 × 10−35). These loci are located near DACT1 and DAAM1, both of which are involved in synapse formation and are key members of the Wnt signaling cascade (51, 52). rs73313052 and high-LD proxies are eQTLs for DAAM1 (t test FDRCMC < 1.0 × 10−2) in the adult cortex (tables S11 and S12). Several of our regional associations occur near genes with known roles in brain development. For example, on chromosome 1p22.2, rs1413536 (associated with the inferior parietal SA: z-score PMA = 1.6 × 10−10; Prep = 3.1 × 10−14) is an eQTL in the adult cortex for LMO4 (t test FDRCMC < 1.0 × 10−2), with chromatin interactions between the region housing both this SNP and rs59373415 (associated with the precuneus SA: z-score PMA = 1.6 × 10−10, Prep = 5.3 × 10−12) and the LMO4 promoter in neural progenitor cells (tables S11 and S12). Lmo4 is one of the few genes already known to be involved in areal identity specification in the mammalian brain (53).

Genetic relationships with other traits

To examine shared genetic effects between cortical structure and other traits, we performed genetic correlation analyses with GWAS summary statistics from 23 selected traits. We observed significant positive genetic correlations between total SA and general cognitive function (54), educational attainment (28), and Parkinson’s disease (27), indicating that allelic influences resulting in larger total SA are, in part, shared with those influencing greater cognitive capabilities as well as increased risk for Parkinson’s disease. For total SA, significant negative genetic correlations were detected with insomnia (55), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (56), depressive symptoms (57), major depressive disorder (58), and neuroticism (29) (Fig. 5A and table S16), again indicating that allelic influences resulting in smaller total SA are partly shared with those influencing an increased risk for these disorders and traits. To map the magnitude of these effects across the brain, we calculated genetic correlations across cortical regions without correction for the global measures (Fig. 5B). Genetic correlations with average TH did not survive multiple testing correction, perhaps owing to the weaker genetic associations detected in the TH analyses. At the regional level, significant genetic correlations were observed between precentral TH and general cognitive function (rG = 0.27, z-score PrG = 2.5 × 10−5) and educational attainment (rG = 0.25, z-score PrG = 4.0 × 10−4), as well as between the inferior parietal TH and educational attainment (rG = −0.19, z-score PrG = 5.0 × 10−4). To confirm that these correlations were not driven by the presence of cases within the meta-analysis, genetic correlations were recalculated from a meta-analysis of GWAS from population-based cohorts and GWAS of controls from the case-control cohorts (N = 28,503 individuals). All genetic correlations remained significant,with the exception of the genetic correlation between total SA and depressive symptoms (table S17).

Fig. 5. Genetic correlations with neuropsychiatric and psychological traits.

(A) Genetic correlations with total SA and average TH. Significant positive correlations are shown in red; significant negative correlations are shown in blue. Error bars indicate SE. (B) Regional variation in the strength of genetic correlations between regional SA (without correction for total SA) and traits showing significant genetic correlations with total SA.

We performed bidirectional Mendelian randomization (MR) (59) and LCV (19) analyses to investigate potential causal relationships underlying the observed genetic correlations with total SA. Both methods provided evidence of a causal effect of total SA on general cognitive function (inverse variance–weighted MR bMR-IVW = 0.15, SE = 0.01, z-score P = 4.6 × 10−8; LCV gcp = 0.40, 95% CIs: 0.23 to 0.57, t test Pgcp=0 = 1.4 × 10−9) and educational attainment (bMR-IVW = 0.12, SE = 0.01, z-score P = 2.1 × 10−21; gcp = 0.49, 95% CIs: 0.26 to 0.72, t test Pgcp=0 = 8.0 × 10−9) (tables S18 and S19). The MR analyses also indicated association in the reverse direction for both general cognitive function and educational attainment (table S18); however, this was not supported by the LCV analyses (table S19). We found limited to no support for a causal relationship in either direction between total SA and the six other traits that showed significant genetic correlations (tables S18 and S19). Taken together, these findings suggest that the previously reported phenotypic relationships between cortical SA and general cognitive function (60, 61) may partly reflect underlying causal processes.

Discussion

Here we present a large-scale collaborative investigation of the effects of common genetic variation on human cortical structure using data from 51,665 individuals from 60 cohorts. Current knowledge of genes that affect cortical structure has been derived largely from creating mutations in model systems, such as the mouse, and observing effects on brain structure (8). Given the differences between mouse and human cortical structures (62), this study provides genome-wide insight into human variation and genes that influence a characteristically human phenotype. Previous studies have identified rare variants that have substantial effects on cortical structure in humans (8), and this study adds to the catalog of the type of variation that affects human cortical structure.

We show that the genetic architecture of the cortex is highly polygenic and that variants often have a specific effect on individual cortical regions. This finding suggests that there are distinct genes involved in the development of specific cortical areas and raises the possibility of developmental and regional specificity in eQTL effects. We also find that rare variants and common variants in similar locations in the genome can lead to similar effects on brain structure, albeit to different degrees. For example, a balanced chromosomal translocation near EOMES leads to microcephaly in a region abutting a common variant signal associated with small changes in cortical SA (fig. S8).

We provide evidence that genetic variation affecting gene regulation in progenitor cell types, present in fetal development, affects adult cortical SA. This is consistent with the radial unit hypothesis, which states that an increase in proliferative divisions of neural progenitor cells leads to an expansion of the pool of progenitors, resulting in increases in neuronal production and cortical SA (3, 62). Notably, we see an enrichment of heritability in cortical SA within regulatory elements that influence outer radial glia cells, a cell type that is considerably more prevalent in gyrencephalic species such as humans and has been hypothesized to account for the increased progenitor pool size in humans (2).

We also find that Wnt signaling genes influence areal expansion in humans, as previously reported in model organisms such as mice (45). Cortical TH was associated with loci near genes implicated in cell differentiation, migration, adhesion, and myelination. Consequently, molecular studies in the appropriate tissues, such as neural progenitor cells and their differentiated neurons, will be critical for mapping the involvement of specific genes.

We demonstrate that genetic variation associated with brain structure also affects general cognitive function, Parkinson’s disease, depression, neuroticism, ADHD, and insomnia. This implies that the genetic variants that influence brain structure also shape brain function. Although most of the differences in cortical structure observed in these disorders have been reported for TH, our results show significant genetic correlations for SA, perhaps suggesting that the phenotypic differences observed in cortical TH (table S1) partially reflect environmental influences or effects of illness or treatment. We find evidence that brain structure is a key phenotype along the causal pathway that leads from genetic variation to differences in general cognitive function and educational attainment.

In summary, this work identifies genomewide significant loci associated with cortical SA and TH and enables a deeper understanding of the genetic architecture of the human cerebral cortex and its patterning.

Materials and methods summary

Participants

Participants were genotyped individuals, with corticalMRI data, from60 cohorts.Participants in all cohorts gave written informed consent, and each site obtained approval from local research ethics committees or institutional review boards. Ethics approval for the metaanalysis was granted by the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute Human Research Ethics Committee (approval: P2204).

Imaging

Measures of cortical SA and TH were derived from in vivo whole-brain T1-weighted MRI scans using FreeSurfer MRI-processing software (1). SA and TH were quantified for each individual across the whole cortex and within 34 distinct gyral-defined regions, according to the Desikan-Killiany atlas. The regions were averaged across both hemispheres (10).

Genetic association analyses

Within each cohort, GWASs were conducted on each of the 70 imaging phenotypes. After quality control, these data were meta-analyzed using METAL (63). Initially the GWASs from European cohorts were meta-analyzed together, yielding the principal results that were used in all subsequent analyses. We sought replication of the genome-wide significant loci with data from the CHARGE Consortium. To examine generalization of effects, the GWASs from the non-European cohorts were meta-analyzed together, and we then collectively meta-analyzed the European and non-European results. Polygenicrisk scores werederived fromthe principal meta-analysis and used to predict the amount of variance explained by the association of common genetic variants with the cortical SA and TH in an independent sample.

SNP heritability and tests for genetic correlations and causation

Heritability explained by common genetic variants (SNP heritability) was estimated using LD score regression (64). Genetic correlations between cortical regions were estimated using cross-trait LD score regression (65). To examine genetic relationships with other traits, we estimated genetic correlations using cross-trait LD score regression. To determine whether these correlations were causal, we used MR (59) and LCV analyses (19).

Partitioned heritability

Partitioned heritability analysis was used to estimate the percentage of heritability explained by annotated regions of the genome (66). Heritability enrichment was first estimated in active regulatory elements across tissues and cell types (21, 22). Subsequently, heritability enrichment was estimated in midfetal–specific active regulatory elements and adult cortex–specific active regulatory elements. Finally, heritability enrichment was estimated in regulatory elements of cell type–specific genes in the fetal brain (23).

Functional follow-up

After obtaining the principal meta-analytic results, we followed up with gene-based association analysis using MAGMA (67). A multivariate analysis of the regional association results was conducted using TATES (42). Pathway analyses were conducted on the global measures and the results from the multivariate analyses using DEPICT to identify enrichment of association in known genetic functional pathways (25). To identify putatively causal variants, we performed fine-mapping with CAVIAR (68). Potential functional impact was investigated using FUMA (30), which annotates the SNP location, nearby enhancers or promoters, chromatin state, associated eQTLs, and the potential for functional effects through predicted effects.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Courtney and M. R. Glass for making panels A and C, respectively, of the summary figure. We thank all cohort participants for making this work possible. We thank the research support staff of all cohorts, including interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists, nurses, carers, participating general practitioners, and pharmacists. In addition, the ALSPAC cohort is grateful to the midwives for their help in recruiting the families who participated in the study and to L. B. Clauss for help during the quality control process of the ALSPAC neuroimaging data. The BETULA cohort thanks the Centre for Advanced Study at the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters in Oslo for hosting collaborative projects and workshops between Norway and Sweden in 2011–2012 and acknowledges that the image analyses were performed on resources provided by the Swedish National Infrastructure for Computing at HPC2N in Umeå. The BONN cohort thanks (in alphabetical order) M. Bartling, U. Broicher, L. Ehrmantraut, A. Maaser, B. Mahlow, S. Mentges, K. Raczka, L. Schinabeck, and P. Trautner for their support and help. The CARDIFF cohort thank researchers at Cardiff University who contributed to the MBBrains panel. The DNS cohort thanks the staff of the Laboratory of NeuroGenetics. The FBIRN cohort thanks L. McMillan for overall study coordination and H. Mangalam, J. Farran, and A. Brenner for administering the University of California, Irvine High-Performance Computing cluster. The GIG cohort thanks M. Keil, E. Diekhof, T. Melcher, and I. Henseler for assistance in data acquisition. The IMpACT cohort acknowledges that, in this work, samples from the Netherlands node of IMpACT were used and the work was carried out on the Dutch national e-infrastructure with the support of the SURF Cooperative. The MCIC cohort thanks colleagues who served as mentors, advisers, and supporters during the inception and conduct of the study, including D. Goff, G. Kuperberg, J. Goldstein, M. Shenton, R. McCarley, S. Heckers, C. Wible, R. Mesholam-Gately, and M. Vangel; staff and clinicians at each site responsible for data acquisition, including S. Wallace, A. Cousins, R. Mesholam-Gately, S. Stufflebeam, O. Freudenreich, D. Holt, L. Kunkel, F. Fleming, G. He, H. Johnson, R. Pierson, A. Caprihan, P. Somers, C. Portal, K. Norman, D. South, M. Doty, and H. Milner; and L. Friedman, S. Posse, J. Jovicich, and T. Wassink for expert guidance on image and other types of data acquisition. MCIC also acknowledges the many research assistants, students, and colleagues who assisted in data curation over the years since data acquisition was completed, including S. Wallace, C. Zyloney, K. Sawlani, J. Fries, A. Scott, D. Wood, R. Wang, W. Courtney, A. Guimaraes, L. Shenkman, M. Kendi, A. T. Karagulle Kendi, R. Muetzel, T. Biehl, and M. Schmidt. The MIRECC cohort thanks the U.S. military veterans who participated in this research. The MPIP cohort thanks R. Schirmer, E. Schreiter, R. Borschke, I. Eidner, and A. Olynyik for supporting MR acquisition and data management, the staff of the Center of Applied Genotyping for generating the genotypes of the Munich Antidepressant Response Signature (MARS) cohort, D. P. Auer for initiating the RUD-MR substudy, E. Binder for supporting participation in ENIGMA, and GlaxoSmithKline for providing the genotypes of the Recurrent Unipolar Depression Case-Control Sample. The PAFIP cohort acknowledges the IDIVAL Neuroimaging Unit for imaging acquirement and analysis and Valdecilla Biobank for help with the technical execution of this work. The PDNZ cohort is grateful to M. MacAskill, D. Myall, L. Livingston, B. Young, and S. Grenfell; staff at the New Zealand Brain Research Institute and Pacific Radiology Christchurch for study coordination and image acquisition; and A. Miller for DNA preparation and banking. The QTIM cohort thanks the many research assistants, radiographers, and IT support staff for data acquisition and DNA sample preparation. The SHIP cohort is grateful to M. Stanke for the opportunity to use his Server Cluster for the SNP imputation, as well as to H. Prokisch and T. Meitinger (Helmholtz Zentrum München) for the genotyping of the SHIPTrend cohort. The Sydney MAS cohort acknowledges that the genome-wide genotyping was performed by the Ramaciotti Centre, University of New South Wales. Acknowledgments from CHARGE replication cohorts: The Austrian Stroke Prevention Family/ Austrian Stroke Prevention Family Study cohort thanks B. Reinhart for her long-term administrative commitment, E. Hofer for technical assistance in creating the DNA bank, I. J. Semmler and A. Harb for DNA sequencing and analyses by TaqMan assays, and I. Poelzl for supervising the quality management processes after ISO9001 at the biobanking and DNA analysis stages. The Cardiovascular Health Study cohort thanks a full list of principal investigators and institutions that can be found at CHS-NHLBI.org. The Framingham Heart Study cohort (CHARGE) especially thanks investigators and staff from the Neurology group for their contributions to data collection. Generation and management of GWAS genotype data for the Rotterdam Study were executed by the Human Genotyping Facility of the Genetic Laboratory of the Department of Internal Medicine, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, Netherlands. The Rotterdam Study cohort thanks P. Arp, M. Jhamai, M. Verkerk, L. Herrera, M. Peters, and C. Medina-Gomez for help with creating the GWAS database and K. Estrada, Y. Aulchenko, and C. Medina-Gomez for creation and analysis of imputed data. The Three-City Dijon cohort thanks A. Boland (CNG) for technical help in preparing the DNA samples for analyses. The investigators of the frontotemporal GWAS (69), the consortia members, and their acknowledgments are listed in the supplementary materials.

Funding: This study was supported by U54 EB020403 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) Initiative, a cross-NIH partnership. Additional support was provided by R01 MH116147, R01MH1161671, P41 EB015922, RF1 AG051710, RF1 AG041915, R56 AG058854, R01 AG059874, R01 MH117601, the Michael J. Fox Foundation (MJFF; 14848), the Kavli Foundation, and National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Project Grant 1158127 (to S.E.M.). S.E.M. was funded by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (APP1103623). K.L.G. was supported by APP1173025. L.C.-C. was supported by a QIMR Berghofer Fellowship. J.L.S. was supported by R01MH118349 and R00MH102357. The 1000BRAINS cohort thanks the Heinz Nixdorf Foundation (Germany) for generous support of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study, which is also supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Science (BMBF; FKZ 01EG940) and the German Research Foundation (DFG; ER 155/6–1). This work was further supported by the BMBF through the Integrated Network IntegraMent under the e:Med Program (01ZX1314A to S.Ci) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (156791 to S.Ci). The Initiative and Networking Fund of the Helmholtz Association supported S.Ca, the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (H2020) supported S.Ci (Human Brain Project SGA1, 720270) and supported S.Ca and S.Ci (Human Brain Project SGA2, 785907). The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI1 and ADNI2GO) was supported by NIH (U01 AG024904) and Department of Defense ADNI (W81XWH-12–2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from AbbVie; Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd., and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer, Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research provided funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions were facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study was coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. Samples used in this study were from the National Centralized Repository for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias, which received government support under a cooperative agreement grant (U24 AG21886) awarded by the NIA. Support for data analysis was provided by NLM R01 LM012535 and NIA R03 AG054936 (to K.N.). The UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and Wellcome (102215/2/13/2) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. A comprehensive list of grants funding is available on the ALSPAC website (www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/external/documents/grant-acknowledgements.pdf). ALSPAC neuroimaging data were specifically funded by RO1 MH085772 (to T.P.). GWAS data were generated by Sample Logistics and Genotyping Facilities at Wellcome Sanger Institute and LabCorp (Laboratory Corporation of America), with support from 23andMe. Data and sample collection by the Australian Schizophrenia Research Bank (ASRB) were supported by the Australian NHMRC, the Pratt Foundation, Ramsay Health Care, and the Viertel Charitable Foundation. The ASRB was also supported by the Schizophrenia Research Institute (Australia), with infrastructure funding from NSW Health and the Macquarie Group Foundation. DNA analysis was supported by the Neurobehavioral Genetics Unit, with funding from NSW Health and the NHMRC Project Grants (1067137, 1147644, 1051672). M.C. was supported by a NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (1121474). C.P. was supported by a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (628386 and 1105825). BETULA was supported by a Wallenberg Scholar grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and a grant from Torsten and Ragnar Söderbergs Foundation to L.N., HelseVest RHF (911554 to S.L.H.), grants from the Bergen Research Foundation and the University of Bergen to S.L.H., grants from the Dr Einar Martens Fund and the K.G. Jebsen Foundation to S.L.H. and V.M.S., and the Research Council of Norway (177458/V 50 to T.E. and 204966/F 20 to L.T.W.). Nijmegen’s BIG resource is part of Cognomics, a joint initiative by researchers of the Donders Centre for Cognitive Neuroimaging, the Human Genetics and Cognitive Neuroscience departments of the Radboud University Medical Center, and the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics (funded by the Max Planck Society). Support for the Cognomics Initiative, including phenotyping and genotyping of BIG cohorts, comes from funds of the participating departments and centers and from external national grants: the Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure (Netherlands) (BBMRI-NL), the Hersenstichting Nederland, and the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), including the NWO Brain & Cognition Excellence Program (433–09-229) and the Vici Innovation Program (016–130-669 to B.F.). Additional support was received from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7) [602805 (Aggressotype), 602450 (IMAGEMEND), and 278948 (TACTICS)], from H2020 [643051 (MiND) and 667302 (CoCA)], and from the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (H2020/EFPIA) [115916 (PRISM)]. BONN was supported by the Frankfurt Institute for Risk Management and Regulation, and B.W. was supported by a Heisenberg Grant of the DFG [WE 4427 (3–2)]. BrainScale was supported by NWO (NWO 51.02.061 to H.E.H.P., NWO 51.02.062 to D.I.B., NWO-NIHC Programs of excellence 433–09-220 to H.E.H.P., NWO-MagW 480–04-004 to D.I.B., and NWO/SPI 56–46414192 to D.I.B.), FP7 Ideas: European Research Council (ERC230374 to D.I.B.), and Universiteit Utrecht (High Potential Grant to H.E.H.P.). CARDIFF genotyping was supported by the National Centre for Mental Health. T.M.L. is funded by a Sêr Cyrmu II Fellowship (East Wales European Regional Development Funds (PNU-80762-CU-14) at the Dementia Research Institute, Cardiff University. DNS received support from Duke University as well as NIH (R01DA033369 and R01DA031579). Work from the London cohort of EPIGEN was supported by research grants from the Wellcome Trust (084730 to S.M.S.), University College London (UCL)/University College London Hospitals (UCLH) National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre/ Specialist Biomedical Research Centres (CBRC/SBRC) (114 to S.M.S.), the Comprehensive Local Research Network Flexibility and Sustainability Funding (CEL1300 to S.M.S.), The Big Lottery Fund, the Wolfson Trust, and the Epilepsy Society. This work was partly undertaken at UCLH/UCL, which received a proportion of funding from the NIHR CBRC/SBRC. FBIRN was supported by the NIH National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) [NIH 1 U24 RR021992 (Function Biomedical Informatics Research Network), NIH 1 U24 RR025736–01 (Biomedical Informatics Research Network Coordinating Center)], the NIH National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR000153), and the NIH through 5R01MH094524, and P20GM103472. This work was supported in part by a Merit Review Award I01CX000497 (J.M.F.) and a Senior Research Career Award (J.M.F.) from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Clinical Sciences Research and Development Service. FOR2107 was funded by the DFG (FOR2107 DA1151/5–1, DA1151/5–2 to U.D.; JA1890/7–1, JA1890/7–2 to A.J.; KI 588/14–1, KI 588/14–2 to T.K.; KR 3822/7–1, KR 3822/7–2 to A.K.; NO246/10–1, NO246/10–2 to M.M.N.). GOBS was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health MH0708143 (to D.C.G.), MH078111 (to J.Bl.), and MH083824 (to D.C.G. and J.Bl.). The Brain Genomics Superstruct Project (GSP) was made possible by the resources provided through Shared Instrumentation Grants 1S10RR023043 and 1S10RR023401 and was supported by funding from the Simons Foundation (to R.L.B.); the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to R.L.B.); NIMH grants R01-MH079799 (to J.W.S.), K24MH094614 (to J.W.S.), and K01MH099232 (to A.J.H.); and the Massachusetts General Hospital–University of Southern California Human Connectome Project (U54MH091665). The HUBIN cohort was supported by the Swedish Research Council (2006–2992, 2006–986, K2007–62X-15077–04-1, K2008–62P-20597–01-3, 2008–2167, 2008–7573, K2010–62X-15078–07-2, K2012–61X-15078–09-3, 14266–01A, 02–03, 2017–949), the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research between Stockholm County Council and the Karolinska Institutet, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, and the HUBIN project. HUNT-MRI was funded by the Liaison Committee between the Central Norway Regional Health Authority and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and the Norwegian National Advisory Unit for functional MRI. IMAGEN was supported by the European Union’s FP6 Integrated Project IMAGEN (LSHM-CT-2007–037286), the H2020 ERC Advanced Grant STRATIFY (695313), ERANID (PR-ST-041610004), BRIDGET (JPND: MR/N027558/1), the FP7 projects IMAGEMEND (602450) and MATRICS (603016), the Innovative Medicine Initiative Project EU-AIMS (115300–2), the Medical Research Foundation and MRC (MR/R00465X/1), the MRC (MR/ N000390/1), the Swedish Research Council FORMAS, the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London, the BMBF (01GS08152, 01EV0711, eMED SysAlc01ZX1311A, Forschungsnetz AERIAL), and the DFG (SM 80/7–1, SM 80/7–2, SFB 940/1). Further support was provided by ANR (AF12-NEUR0008–01 – WM2NA, and ANR-12-SAMA-0004), the Fondation de France, the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, the Mission Interministérielle de Lutte-contre-les-Drogues-et-les-ConduitesAddictives (MILDECA), the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (DPA20140629802), the Fondation de l’Avenir, Paris Sud University IDEX 2012, Science Foundation Ireland (16/ERCD/3797), and the NIH (RO1 MH085772–01A1). IMH was supported by National Healthcare Group, Singapore (SIG/05004; SIG/05028), and Singapore Bioimaging Consortium (RP C-009/2006) research grants awarded to K.S.; M.La. was supported by a National Medical Research Council Research Training Fellowship (MH095: 003/008–1014) and Singapore Ministry of Health National Medical Research Council Center Grant (NMRC/CG/004/2013). IMpACT was supported by the NWO (433–09-229) and the Vici Innovation Program (016–130-669 to B.F.). Additional support was received from the ERC under FP7 [602805 (Aggressotype), 602450 (IMAGEMEND), and 278948 (TACTICS)] as well as from H2020 [643051 (MiND), 667302 (CoCA), and 728018 (Eat2beNICE)]. LBC1936 was supported by a Research into Aging program grant (to I.J.D.) and the Age UK-funded Disconnected Mind project www.disconnectedmind.ed.ac.uk; to I.J.D. and J.M.W.), with additional funding from the UK MRC (Mr/M01311/1, G1001245/96077, G0701120/79365 to I.J.D., J.M.W. and M.E.B.). The whole-genome association part of this study was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC; BB/F019394/1). J.M.W. is supported by the Scottish Funding Council through the SINAPSE Collaboration (www.sinapse.ac.uk). CCACE (MRC MR/K026992/1) is funded by the BBSRC and MRC. LIBD was supported by direct funding from the NIMH intramural research program of the NIH to the Weinberger laboratory and by support from the Lieber Institute for Brain Development and the Maltz Research Laboratories. MCIC was supported primarily by U.S. Department of Energy DE-FG0299ER62764 through its support of the Mind Research Network (MRN, formerly known as the MIND Institute) and the consortium as well as by the National Association for Research in Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders (NARSAD) Young Investigator Award (to S.Eh.), through the Blowitz-Ridgeway and Essel Foundations and a ZonMw TOP 91211021 (to T.Wh.), a DFG research fellowship (to S.Eh.), the MRN, the NIH through NCRR 5MO1-RR001066 (MGH General Clinical Research Center), NIMH K08 MH068540, the Biomedical Informatics Research Network with NCRR Supplements to P41 RR14075 (MGH), M01 RR 01066 (MGH), NIBIB R01EB006841 (MRN), R01EB005846 (MRN), 2R01 EB000840 (MRN), 1RC1MH089257 (MRN), as well as grant U24 RR021992. Meth-CT was supported by the Medical Research Council, South Africa. MIRECC was supported by NIMH (1R01MH111671) and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VISN6 MIRECC). MooDS was supported by the BMBF grants [National Genome Research Network Plus (MooDS: Systematic Investigation of the Molecular Causes of Major Mood Disorders and Schizophrenia, www.ngfn.de/en/schizophrenie.html); e:Med Programme: Integrated Network IntegraMent (01ZX1314A to M.M.N.; 01ZX1614A to F.D. and M.M.N.)] and by DFG (FOR 1617) as well as Excellence Cluster (EXC 257). MPIP was supported by a grant of the Exzellenz-Stiftung of the Max Planck Society and by the BMBF National Genome Research Network (FKZ 01GS0481). MPRC was supported by the NIH (R01MH116948, R01MH112180, U01MH108148, UG3DA047685, 2R01EB015611, R01DA027680, R01MH085646, P50MH103222, U54 EB020403, and T32MH067533), NSF (IIS-1302755 and MRI-1531491), a state of Maryland contract (M00B6400091), and a Pfizer research grant. MÜNSTER was funded by the DFG (SFB-TRR58, Projects C09 and Z02 to U.D.) and the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research of the medical faculty of Münster (Dan3/012/17 to U.D.). NCNG was supported by the Bergen Research Foundation, the University of Bergen, the Research Council of Norway [FUGE (151904 and 183327), Psykisk Helse (175345), RCN (154313/V50 to I.R. and 177458/V50 to T.E.)], Helse Sørøst RHF (2012086 to T.E.), and the Dr Einar Martens Fund. NESDA obtained funding from the NOW (Geestkracht program 10–000-1002), the Center for Medical Systems Biology (CSMB, NWO Genomics), BBMRI-NL, VU University’s Institutes for Health and Care Research (EMGO+) and Neuroscience Campus Amsterdam, University Medical Center Groningen, Leiden University Medical Center, and NIH (R01D0042157–01A, MH081802, Grand Opportunity grants 1RC2 MH089951 and 1RC2 MH089995). Parts of the genotyping and analyses efforts were funded by the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN) of the FNIH. Computing was supported by BiG Grid, the Dutch e-Science Grid, which is financially supported by NWO. The NeuroIMAGE study was supported by NIH grant R01MH62873, NWO Large Investment Grant 1750102007010 (to J.K.B.), ZonMW grant 60–60600-97–193, NWO grants 056–13-015 and 433–09-242, and matching grants from Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, University Medical Center Groningen and Accare, and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Further support was received from the FP7 [278948 (TACTICS), 602450 (IMAGEMEND), 602805 (Aggressotype)], and H2020 [667302 (CoCA) and 728018 (Eat2beNICE)]. The Netherlands Twin Register (NTR) obtained funding from NWO and ZonMW grants (904–61-090, 985–10-002, 912–10-020, 904–61-193,480–04-004, 463–06-001, 451–04-034, 400–05-717, Addiction-31160008, 016–115-035, 481–08-011, 056–32-010, Middelgroot-911–09-032, OCW_NWO Gravity program – 024.001.003, NWO-Groot 480–15-001/674), Center for Medical Systems Biology (CSMB, NWO Genomics), NBIC/BioAssist/RK (2008.024), BBMRI–NL (184.021.007 and 184.033.111); Spinozapremie (NWO-56–464-14192), KNAW Academy Professor Award (PAH/6635), and University Research Fellow grant to D.I.B.; Amsterdam Public Health research institute (former EMGO+), Neuroscience Amsterdam research institute (former NCA); the European Science Foundation (EU/QLRT-2001–01254), FP7 [FP7HEALTH-F4–2007-2013: 01413 (ENGAGE) and 602768 (ACTION)]; the ERC (ERC Advanced, 230374, ERC Starting grant 284167), Rutgers University Cell and DNA Repository (NIMH U24 MH068457–06), the NIH (R01D0042157–01A1, R01MH58799–03, MH081802, DA018673, R01 DK092127–04, Grand Opportunity grants 1RC2 MH089951, and 1RC2 MH089995); and the Avera Institute for Human Genetics. Parts of the genotyping and analyses efforts were funded by the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN) of the FNIH. Computing was supported by NWO through 2018/EW/00408559, BiG Grid, the Dutch e-Science Grid and SURFSARA. OATS was supported by the Australian NHMRC/ Australian Research Council Strategic Award (401162) and NHMRC Project Grant (1405325). The study was facilitated through Twins Research Australia, a national resource partly supported by a Centre for Research Excellence from the NHMRC. DNA was extracted by Genetic Repositories Australia (NHMRC grant 401184). Genome-wide genotyping at the Diamantina Institute, University of Queensland, was partly funded by a CSIRO Flagship Collaboration Fund Grant. OSAKA was supported by AMED under JP18dm0307002, JP18dm0207006 (Brain/MINDS) and JSPS KAKENHI J16H05375. PAFIP was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI14/00639 and PI14/00918), MINECO (SAF201020840-C02–02 and SAF2013–46292-R), and Fundación Instituto de Investigación Marqués de Valdecilla (NCT0235832 and NCT02534363). PDNZ was supported by the Health Research Council, the Neurological Foundation of New Zealand, Canterbury Medical Research Foundation, University of Otago Research Grant, and Jim and Mary Carney Charitable Trust (Whangarei, New Zealand). PING was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (RC2DA029475) and the U.S. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD061414). Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI), a public-private partnership, is funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and funding partners, including AbbVie, Allegran, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Biogen Idec, BioLegend, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Denali Therapeutics, GE Healthcare, Genentech, GSK-GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly & Co., F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd., Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals, Merck & Co., MSD-Meso Scale Discovery, Pfizer, Piramal, Sanofi Genzyme, Servier, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, TEVA Pharmaceutical Industries, UCB Pharma SA, and Golub Capital (www.ppmi-info.org/about-ppmi/who-we-are/study-sponsors/). QTIM was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD050735), National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (Award 1U54EB020403–01, Subaward 56929223), and NHMRC (Project Grants 496682, 1009064 and Medical Bioinformatics Genomics Proteomics Program 389891). SHIP is part of the Community Medicine Research net of the University of Greifswald, Germany, which is funded by the DFG (01ZZ9603, 01ZZ0103, and 01ZZ0403), the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, the Social Ministry of the Federal State of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania, and the network “Greifswald Approach to Individualized Medicine (GANI_MED)” funded by the DFG (03IS2061A).

Whole-body MRI was supported by a joint grant from Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany, and the federal state of Mecklenburg–West Pomerania. Genome-wide data have been supported by the DFO (03ZIK012) and a joint grant from Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany, and the federal state of Mecklenburg–West Pomerania. The University of Greifswald is a member of the Caché Campus program of InterSystems, GmbH. Sydney MAS was supported by the NHMRC/Australian Research Council Strategic Award (401162) and NHMRC Program Grants (350833, 568969). DNA was extracted by Genetic Repositories Australia (NHMRC Grant 401184). SYS has been funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Computations were performed on the GPC supercomputer at the SciNet HPC Consortium. SciNet is funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation under the auspices of Compute Canada; the government of Ontario; Ontario Research Fund–Research Excellence, and the University of Toronto. TCDNUIG included data from two sites. NUI Galway data collection was supported by the Health Research Board (HRA_POR/2011/100). Trinity College Dublin was supported by The Science Foundation Ireland Research Investigator project (12.IP.1359 to G.D.). TOP and TOP3T are part of TOP, which is supported by the Research Council of Norway (223273, 213837, 249711, 226971, 262656), the South East Norway Health Authority (2017–112), the Kristian Gerhard Jebsen Stiftelsen (SKGJ-MED-008), and the FP7 [602450 (IMAGEMEND)]. UiO2016 and UiO2017 are part of TOP and STROKEMRI, which are supported by the Norwegian ExtraFoundation for Health and Rehabilitation (2015/FO5146), the Research Council of Norway (249795, 248238), and the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (2014097, 2015044, 2015073). The UMCU cohort consists of several independent studies, which were supported by ZonMw TOP 40–008-12–9813009, the Geestkracht program of the ZonMw (10–000-1001), the Stanley Medical Research Institute (Dr. Nolen), the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (2013–2015 NARSAD Independent Investigator grant 20244 to M.H.J.H.), NWO (2012–2017 VIDI grants 452–11-014 to N.E.M.v.H. and 917–46-370 to H.E.H.P.), and ZonMw (908–02-123 to H.E.H.P.). UNICAMP was supported by FAPESP (São Paulo Research Foundation) 2013/07559–3: the Brazilian Institute of Neuroscience and Neurotechnology (BRAINN). Collection of chimpanzee brain images was supported by the NIH (NS-42867, NS-73134, and NS-92988). The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the NIH; or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Infrastructure for the CHARGE Consortium is supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI; HL105756) and for the neuroCHARGE phenotype working group through the NIA (AG033193). H.H.H.A. was supported by the Netherlands Organization for the Health Research and Development (ZonMw; 916.19.151). The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC) was a collaborative study supported by the NHLBI (HHSN268201100005C, HSN268201100006C, HSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, HHSN268201100012C, R01HL70825, R01HL087641, R01HL59367, and R01HL086694); the National Human Genome Research Institute (U01HG004402); and the NIH (HHSN268200625226C). Infrastructure was partly supported by UL1RR025005, a component of the NIH and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. This project was partially supported by NIH R01 grants HL084099 and NS087541 (to M.Fo.). The Austrian Stroke Prevention Family/Austrian Stroke Prevention Family Study databank was supported by the Medical University of Graz and the Steiermärkische Krankenanstaltengesellschaft. The research reported in this article was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (PI904, P20545-P05 and P13180), the Austrian National Bank Anniversary Fund (P15435), and the Austrian Ministry of Science under the aegis of the EU Joint Programme–Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND; www.jpnd.eu). The Cardiovascular Health Study was supported by NHLBI (HHSN268201200036C, HHSN268200800007C, N01HC55222, N01HC85079, N01HC85080, N01HC85081, N01HC85082, N01HC85083, N01HC85086, U01HL080295, R01HL087652, R01HL105756, R01HL103612, R01HL120393, and R01HL130114), with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Additional support was provided through R01AG023629, R01AG15928, and R01AG033193 from the NIA. The provision of genotyping data was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, CTSI grant UL1TR000124, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease Diabetes Research Center grant DK063491 to the Southern California Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center. The Erasmus Rucphen Family Study was supported by the Consortium for Systems Biology, within the framework of the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (NGI)/NWO. ERF as a part of EUROSPAN (European Special Populations Research Network) was supported by the European Commission’s 5th Framework Programme (FP5) (QLG2-CT-2002–01254), the FP6 (018947; LSHG-CT-2006–01947), and the FP7 (HEALTH-F4–2007-201413 and 602633). High-throughput analysis of the ERF data was supported by a joint grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research and the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (NWO-RFBR 047.017.043). High-throughput metabolomics measurements of the ERF study were supported by BBMRI-NL. The Framingham Heart Study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Framingham Heart Study (N01-HC25195 and HHSN268201500001I) and its contract with Affymetrix, Inc., for genotyping services (N02-HL-6–4278). A portion of this research used the Linux Cluster for Genetic Analysis (LinGA-II) funded by the Robert Dawson Evans Endowment of the Department of Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine and Boston Medical Center. This study was also supported by grants from the NIA (R01s AG033040, AG033193, AG054076, AG049607, AG008122, AG016495, and U01-AG049505) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS017950). C.Dec. is supported by the Alzheimer’s Disease Center (P30 AG 010129). LIFE-Adult: LIFE-Adult is funded by the Leipzig Research Center for Civilization Diseases (LIFE). LIFE is an organizational unit affiliated with the Medical Faculty of the University of Leipzig. LIFE is funded by means of the European Union, the European Regional Development Fund, and funds of the Free State of Saxony within the framework of the excellence initiative. This work was also funded by the DFG (CRC 1052 “Obesity mechanisms” project A1) and the Max Planck Society. The Rotterdam Study was funded by Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University, Rotterdam; ZonMw; the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (RIDE); the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science; the Ministry for Health, Welfare and Sports; the European Commission (DG XII); and the municipality of Rotterdam. The GWAS datasets are supported by NWO Investments (175.010.2005.011, 911–03-012); the Genetic Laboratory of the Department of Internal Medicine, Erasmus MC; the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (014–93-015; RIDE2); and the NGI/NWO Netherlands Consortium for Healthy Aging (050–060810). This work was performed as part of the CoSTREAM project (www.costream.eu) and received funding from H2020 (667375). The Three-City Dijon study was conducted under a partnership agreement among the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), the University of Bordeaux, and Sanofi-Aventis. The Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale funded the preparation and initiation of the study. The 3C Study is also supported by the Caisse Nationale Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés, Direction Générale de la Santé, Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale, Institut de la Longévité, Conseils Régionaux of Aquitaine and Bourgogne, Fondation de France, and Ministry of Research–INSERM Programme “Cohortes et collections de données biologiques.” S.Deb. received investigator-initiated research funding from the French National Research Agency (ANR) and from the Fondation Leducq. S.Deb. is supported by a starting grant from the European Research Council (SEGWAY), a grant from the Joint Programme of Neurodegenerative Disease research (BRIDGET), H2020 (643417 and 640643), and the Initiative of Excellence of Bordeaux University. This work was supported by the National Foundation for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, the Institut Pasteur de Lille, the labex DISTALZ, and the Centre National de Génotypage. The Vietnam Era Twin Study of Aging (VETSA) was supported by the U.S. NIH VA San Diego Center of Excellence for Stress and Mental Health R00DA023549, DA-18673, NIA R01 AG018384, R01 AG018386, R01 AG022381, R01 AG022982, R01 DA025109 05, R01 HD050735, K08 AG047903, R03 AG 046413, and R01 HD050735–01A2.

Competing interests: A.M.D. is a Founder of CorTechs Labs, Inc., and has received funding through a Research Agreement between General Electric Healthcare and the University of California, San Diego. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by the University of California, San Diego, in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. B.F. has received educational speaking fees from Shire and Medice. B.W.J.H.P. has received (nonrelated) research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim and Janssen Research. C.D.W. is currently an employee of Biogen. C.R.J. consults for Lilly and serves on an independent data monitoring board for Roche but receives no personal compensation from any commercial entity. C.R.J. receives research support from NIH and the Alexander Family Alzheimer’s Disease Research Professorship of the Mayo Clinic. D.H.M. is a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, GW/Greenwhich Biosciences, and Aptinyx. D.J.S. has received research grants and/or consultancy honoraria from Lundbeck and Sun. D.P.H. is currently an employee of Genentech, Inc., and was previously employed by Janssen R&D, LLC. H.B. is on the advisory board for Nutricia Australia. R.S.K. has consulted for Alkermes, Otsuka, Luye Pharma, and Sunovion and has received speaker fees from Janssen-Cilag and Lundbeck. None of the other authors declare any competing financial interests. H.J.G. has received travel grants and speaker honoraria from Fresenius Medical Care, Neuraxpharm, and Janssen Cilag. H.J.G. has received research funding from the German Research Foundation, the German Ministry of Education and Research, the DAMP Foundation, Fresenius Medical Care, the EU Joint Programme Neurodegenerative Disorders, and the European Social Fund. L.E.H. has received or is planning to receive research funding or consulting fees from Mitsubishi; Your Energy Systems, LLC; Neuralstem; Taisho; Heptares; Pfizer; Sound Pharma; Luye Pharma; Takeda; and Regeneron. N.H. is a stockholder of Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany. R.B. has received travel grants and speaker honoraria from Bayer Healthcare, AG. R.L.B. is a paid consultant for Roche.

Footnotes

Data and materials availability: The metaanalytic results presented in this paper are available to download from the ENIGMA consortium website (http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/research/download-enigma-gwas-results). Access to cohort data is available either through public repositories or directly from the cohort. Direct requests are required when informed consent or the approved study protocol does not permit deposition into a repository. Requests for data by qualified investigators are subject to scientific and ethical review to ensure that the data will be used for valid scientific research and to ensure compliance with confidentiality, consent, and data protection regulations. Some of the data are subject to material transfer agreements or data transfer agreements, and specific details on how to access data for each cohort are available in table S20.

Consortium authors are listed in the supplementary materials.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Fischl B, FreeSurfer. Neuroimage 62, 774–781 (2012). doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lui JH, Hansen DV, Kriegstein AR, Development and evolution of the human neocortex. Cell 146, 18–36 (2011). doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.030; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakic P, Specification of cerebral cortical areas. Science 241, 170–176 (1988). doi: 10.1126/science.3291116; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson PM et al. , ENIGMA and global neuroscience: A decade of large-scale studies of the brain in health and disease across more than 40 countries. PsyArXiv (4 July 2019). doi: 10.31234/osf.io/qnsh7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panizzon MS et al. , Distinct genetic influences on cortical surface area and cortical thickness. Cereb. Cortex 19, 2728–2735 (2009). doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp026; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winkler AM et al. , Cortical thickness or grey matter volume? The importance of selecting the phenotype for imaging genetics studies. Neuroimage 53, 1135–1146 (2010). doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.028; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strike LT et al. , Genetic complexity of cortical structure: Differences in genetic and environmental factors influencing cortical surface area and thickness. Cereb. Cortex 29, 952–962 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bae BI, Jayaraman D, Walsh CA, Genetic changes shaping the human brain. Dev. Cell 32, 423–434 (2015). doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.01.035; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meechan DW, Maynard TM, Tucker ES, LaMantia AS, Three phases of DiGeorge/22q11 deletion syndrome pathogenesis during brain development: Patterning, proliferation, and mitochondrial functions of 22q11 genes. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci 29, 283–294 (2011). doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2010.08.005; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]