Abstract

A 60-year-old man presented with right third nerve palsy and headaches. Neuroimaging showed a pituitary lesion. There was evidence of rapid enlargement on interval scans, invasion of the cavernous sinus and displacement of the pituitary stalk. He subsequently developed anterior hypopituitarism. CT thorax, abdomen and pelvis did not show any evidence of malignancy. This was thought to be an aggressive pituitary macroadenoma but histology post-trans-sphenoidal surgery surprisingly showed metastasis from an undiagnosed prostate primary. His prostate specific antigen was raised and MRI pelvis confirmed locally advanced prostate cancer.

Keywords: pituitary disorders, prostate cancer, radiotherapy

Background

This is a rare case of pituitary metastasis from a prostate primary carcinoma. It is often misdiagnosed as aggressive pituitary adenoma preoperatively unless a systemic metastatic disease is already present. The majority of the cases reported in the literature were known to have prostate cancer. Our case was unusual in that it was the first presentation of prostate cancer. The diagnosis was established by endoscopic trans-sphenoidal resection of the pituitary lesion. This was delayed by patient’s extreme hospital phobia. Clinicians need to maintain a high index of suspicion for metastasis in a rapidly enlarging pituitary lesions causing rapid pituitary dysfunction.

Case presentation

A 60-year-old man presented to his local hospital with headache, right-sided facial pain and intermittent diplopia in the right eye of less than 1-week duration. His prior medical history included hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. He was on bisoprolol, ramipril, aspirin and simvastatin. The examination demonstrated partial right third nerve palsy.

CT brain showed a pituitary lesion. Renal, thyroid and liver function tests, full blood count, bone profile, urea and electrolytes, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were normal.

Urgent outpatient MRI pituitary was rescheduled several times due to his non-attendance as a result of hospital phobia. This was performed a month later which showed 7×21×15 mm sellar mass invading the right cavernous sinus, displacing the pituitary stalk to the left suggestive of pituitary macroadenoma (figure 1). Clival invasion was also noted. There was a significant enlargement of the lesion when compared with CT scan a month before in keeping with an aggressive lesion but there was no chiasmal compression.

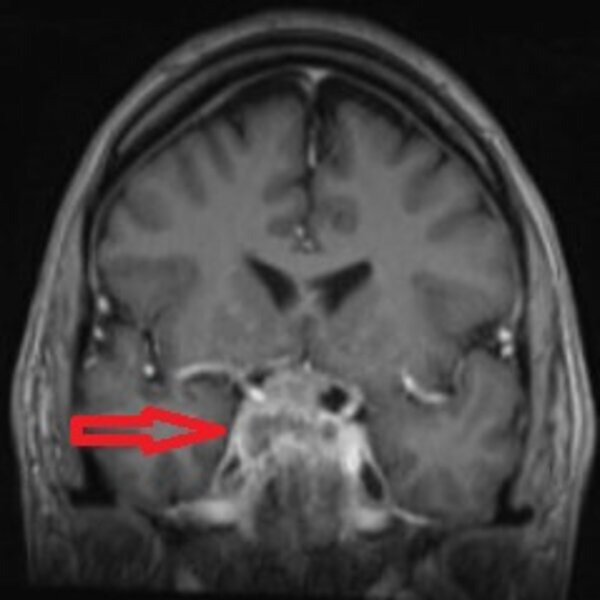

Figure 1.

Coronal T1-weighted view of the pituitary gland showing pituitary lesion (red arrow) involving the right cavernous sinus but clear of the optic chiasm.

Pituitary function tests (table 1) revealed a secondary hypogonadism only. There were no visual field defects.

Table 1.

Initial investigations

| Parameter | Patients results | Reference range |

| Prolactin | 236 mU/L | 73–407 |

| TSH | 1.51 mU/L | 0.30–4.40 |

| T4 | 14.7 pmol/L | 9.0–19.1 |

| FSH | 8.7 IU/L | 1.0–12.0 |

| LH | 3.5 IU/L | 1.0–9.0 |

| Testosterone | 1.5 nmol/L | 9.7–38.2 |

| IGF-1 | 17.8 nmol/L | 4.0–25.0 |

| Short synacthen test | Basal cortisol—305 nmol/L 30 min Cortisol—913 nmol/L |

|

| Adj calcium | 2.37 mol/L | 2.20–2.60 |

Bold highlights the abnormal results.

FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; IGF-1, insulin like growth factor-1; LH, luteinising hormone; TSH, thyroid stimulation hormone.

These findings and the possible need for neurosurgical intervention were explained to him but he refused the possibility of overnight hospital stay due to his extreme hospital phobia and appeared fatalistic about the diagnosis throughout the consultation. On one occasion, he became very angry and walked out of the clinic. Most of the conversation would take place with his wife who was very supportive.

He was referred to our tertiary care pituitary multi-disciplinary team (MDT) meeting. An aggressive pituitary subtype was suspected in view of the radiological features but given normal vision and difficulty engaging with medical advice, close surveillance was advised.

There was evidence of further enlargement of the lesion (20×30×19 mm) on MRI pituitary 3 months later invading the posterior sphenoid sinus. Visual fields remained intact.

Repeat 3 monthly MRI showed further enlargement of the lesion predominantly on the right now compressing the distal right optic nerve and more prominent compression of the right cavernous sinus.

Outcome from rediscussion in the MDT was to rule out metastasis. CT thorax, abdomen and pelvis did not show any evidence of malignancy particularly in the prostate gland and pelvic bones. He continued to have symptoms of headache, right facial pain which was thought to be related to involvement of trigeminal nerve in the cavernous sinus. Repeat pituitary profile 9 months after the initial presentation showed partial anterior hypopituitarism (table 2). He was started on steroid replacement followed by thyroxine. There were no symptoms suggestive of diabetes insipidus.

Table 2.

Subsequent investigations

| Parameter | Patients results | Reference range |

| Prolactin | 560 mU/L | 73–407 |

| TSH | 1.01 mU/L | 0.30–4.40 |

| T4 | 6.6 pmol/L | 9.0–19.1 |

| T3 | 2.0 pmol/L | 2.6–5.7 |

| FSH | 3.2 IU/L | 1.0–12.0 |

| LH | 2.3 IU/L | 1.0–9.0 |

| Testosterone | 1.4 nmol/L | 9.7–38.2 |

| IGF-1 | 15.6 nmol/L | 4.0–25.0 |

| PSA | 79.9 µg/L | <4.0 |

| Cortisol | 235 nmol/L |

FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; IGF-1, insulin like growth factor-1; LH, luteinising hormone; PSA, postate-specific antigen; TSH, thyroid stimulation hormone.

In view of the rapidly enlarging lesion causing rapid anterior hypopituitarism and possible threat to sight, it was decided to proceed with pituitary surgery. He agreed to it after a lot of persuasion but was not happy with the need for 3 days postoperative hospital stay. In order to allay his fears and deal with his hospital phobia, it was suggested that he should get more familiar with the ward environment and meet the staff. This is also called exposure therapy which is a well-known technique in behavioural therapy in the treatment of anxiety disorders. He was, therefore, invited to visit the neurosurgical unit, but in spite of this, he pulled out of a scheduled date for surgery. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA), checked routinely prior to starting testosterone replacement, was significantly high (table 2). This was 7 months after his initial presentation. When asked about prostate symptoms he did have some frequency of micturition but no obstructive symptoms. He was referred to Urology clinic but did not attend two appointments which led to a further delay of 7 months before he saw the urology team who initially requested an MRI of his pelvis which showed abnormal signal in the prostate consistent with carcinoma and bilateral metastatic deposits in the pelvis. Tumour, nodes and metastasis (TNM) staging was T3B No M1B. Before he could have a prostate biopsy, he was admitted to his local hospital with worsening headache and new left third nerve palsy and was transferred as an emergency to the neurosurgical unit in our hospital. Repeat MRI prior to surgery was reported as locally invasive complex heterogeneously enhancing sellar mass with bilateral cavernous sinus and carotid siphon involvement and compression of the chiasm and right optic nerve. There was extension to the orbital apices bilaterally. The pituitary lesion was significantly larger (37×30×37 mm) compared with his initial MRI 15 months ago (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Coronal T1-weighted MRI of pituitary gland performed 15 months after his initial MRI, showing further enlargement of the lesion (red arrow) with local invasion into cavernous sinuses, carotid siphon and compression of the optic chiasm and right optic nerve.

He had endonasal debulking of the pituitary lesion which was found to be firm and adherent to the right carotid artery and optic nerve. His postoperative stay was uneventful. Histology of the lesion showed glandular adenocarcinoma with nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia and immunohistochemistry showing nuclear labelling of prostate carcinoma cells with antibody consistent with metastasis from a prostate carcinoma (figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Glandular adenocarcinoma with nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia (top) adjacent to normal anterior pituitary acini (bottom) (H&E).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry—nuclear labelling of prostate carcinoma cells with antibody (stained) (top) and with normal anterior pituitary cells unstained (bottom).

Following discusion in the skull base and urology MDTs, he was started on bicalutamide and had 10 sessions of radiotherapy to the skull base. Urology decided not to proceed with a prostate biopsy given the high PSA, radiological findings and pituitary biopsy confirmation of metastatic prostate cancer.

Radiotherapy resulted in improvement in his headaches and third nerve palsy. He is currently under urology, oncology and endocrinology follow-up.

Differential diagnosis

The two main contenders in the differential diagnoses in this case were: (1) aggressive type of non-functioning pituitary macroadenoma and (2) metastasis from primary malignancy elsewhere.

The former diagnosis was favoured due to lack of evidence for the latter, that is, the absence of diabetes insipidus and normal non-contrast CT imaging of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis. High PSA levels done prior to trans-sphenoidal surgery routinely before commencing testosterone replacement gave a clue to the possible underlying diagnosis but the final confirmation came from histopathology of the resected pituitary specimen.

Pituitary carcinoma is another rare disease that accounts for approximately 0.2% of all pituitary masses which tend to metastasise making it difficult to differentiate from pituitary metastasis. Histopathology is the gold standard in this situation.

Outcome and follow-up

This patient is still alive and is currently being followed up in the oncology and endocrinology clinics. He has improvement in headache and left third nerve palsy. He is not for further neurosurgery and would continue on bicalutamide. His PSA levels have reduced from 79.9 µg/L to 50.4 µg/L.

Discussion

Pituitary metastasis from any primary malignancy is rare and it is even rarer from prostate carcinoma. The first case of metastasis to the pituitary gland was described in 1857 by Benjamin in an autopsy of a patient with disseminated melanoma.1 Since then, there are reports of various primary malignancies metastasising to the pituitary gland.

A retrospective review by Javanbakht et al found 11 cases of pituitary metastasis between 1984 and 2018. None of them were related to prostate carcinoma. Breast cancer and lymphoma were the most common primary malignancies.2

The group also looked at all the reported cases of pituitary metastasis in the literature from 1957 until 2018 and identified a total of 289 cases. Only eight cases (2.7%) were due to prostatic carcinoma. Breast, lung and thyroid were by the far the most common primaries.2

As the vascular supply to the posterior pituitary is derived directly from the systemic circulation via the internal carotid arteries, the posterior pituitary is the preferred site for blood-borne metastatic spread, whereas the anterior pituitary receives blood from the hypophyseal portal system.3 This can cause disruption to the production of anti-diuretic hormone or vasopressin resulting in diabetes insipidus in about 29%–71% cases.4

It is not easy to differentiate between a pituitary adenoma and pituitary metastasis.

If extensive bony erosion is present and disease onset is rapid, the diagnosis of metastasis is more readily apparent. However, pituitary imaging may not clearly distinguish metastatic deposits from a pituitary adenoma; these lesions may masquerade as an adenoma and the diagnosis only made by histological study of the resected specimen.5

Our case had clues favouring the diagnosis of metastasis, that is, rapid expansion on interval scans but there was no evidence of primary malignancy until routine PSA level was found to be raised just prior to planning for trans-sphenoidal surgery.

In a retrospective study, Ariel et al looking at the clinical characteristics and pituitary dysfunction in patients with metastatic cancer to the sella identified that the most common presenting signs and symptoms were headache (58%), followed by fatigue (50%), polyuria (50%), visual field defects (42%) and ophthalmoplegia (42%).6

Our patient presented with headaches, right-sided third nerve palsy suggestive of compression of occulomotor nerve in the cavernous sinus. This gradually improved but later on developed left-sided third nerve palsy. He also reported right facial pain which was thought to be related to compression of V1 and V2 branches of trigeminal nerve.

He did not have symptoms of diabetes insipidus and his visual fields were intact.

Patel et al reported a case of pituitary metastasis from prostate carcinoma in a patient with known metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate. He presented with bitemporal hemianopia.7

Riemenschneider et al published a case of pituitary metastasis in a patient with known advanced prostate adenocarcinoma. He presented with isolated sixth cranial nerve palsy. There was no parasellar osseous involvement.8

The challenging issue in this case was our patient’s severe hospital phobia which led to several cancellations and rearrangements of hospital follow-up appointments for clinic review and MRI scans and refusal to have intravenous canula for administration of contrast. His phobia stemmed from previous experience during tonsillectomy as a child. It was quite clear that he had mental capacity. We had limited options in dealing with his phobia as he would not engage with psychiatric services. We tried to get as much support from his wife as we could, communicated with him through regular phone calls and letters and exposure/desensitisation therapy in the form of a planned visit to the neurosurgical unit.

Learning points.

Think about metastasis in a rapidly enlarging pituitary lesion even if there is no apparent history of primary malignancy.

Although pituitary metastasis usually causes diabetes insipidus, its absence does not rule out its possibility.

A thorough history and examination is the key to look for primary malignancy when there is suspicion of metastasis and tumour markers, for example, prostate-specific antigen might help.

It is difficult to differentiate pituitary metastasis from adenoma but evidence of rapid enlargement, invasion of the bone and presence of diabetes insipidus favours metastasis.

A multi-disciplinary approach is required when dealing with patients having hospital phobia. This includes good communication, involvement of the family members, pharmacological and psychiatric support.

Footnotes

Contributors: SA, consultant physician/Endocrinologist, wrote case report and discussion with literature search and references. Obtained informed consent from patient. FS, consultant physician/ Endocrinologist, reviewed and authorised the final version of the abstract. CH, consultant Neurosurgeon, reviewed and authorised the final version of the abstract. AL, consultant physician/ Endocrinologist, reviewed and authorised the final version of the abstract.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Komninos J, Vlassopoulou V, Protopapa D, et al. . Tumors metastatic to the pituitary gland: case report and literature review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:574–80. 10.1210/jc.2003-030395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Javanbakht A, D'Apuzzo M, Badie B, et al. . Pituitary metastasis: a rare condition. Endocr Connect 2018;7:1049–57. 10.1530/EC-18-0338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Post KD. Pituitary metastases: what is the role of surgery? World Neurosurg 2013;79:251–2. 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laws E, Sheehan J. Sellar and Parasellar tumors, diagnosis, treatments, and outcomes. TNY, 2011ISBN:1604064226. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sidiropoulos M, Syro LV, Rotondo F, et al. . Melanoma of the sellar region mimicking pituitary adenoma. Neuropathology 2013;33:175–8. 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2012.01331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ariel D, Sung H, Coghlan N, et al. . Clinical characteristics and pituitary dysfunction in patients with metastatic cancer to the sella. Endocr Pract 2013;19:914–9. 10.4158/EP12407.OR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel N, Teh BS, Powell S, et al. . Rare case of metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma to the pituitary. Urology 2003;62:352. 10.1016/S0090-4295(03)00367-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riemenschneider MJ, Beseoglu K, Hänggi D, et al. . Prostate adenocarcinoma metastasis in the pituitary gland. Arch Neurol 2009;66:1036–7. 10.1001/archneurol.2009.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]