Abstract

A patient can develop cognitive dysfunction and neuroinflammation after surgery. However, it is not known whether these pathological processes occur in people who live together with surgery patients. As an initial step to address this issue in animals, 2 mice with right common carotid arterial exposure were cage-mates with 3 non-surgery mice. Their learning and memory were tested starting 5 days after surgery. Their brain tissues were harvested 1 day or 5 days after surgery. The results showed that mice with surgery and cage-mates of these surgery mice had increased pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain and dysfunction of learning and memory. Inhibition of inflammation attenuated the cognitive impairment of the cage-mates. These results suggest that dysfunction of complex behavior including learning and memory can occur in non-surgery cage-mates of surgery mice. Additional studies are needed to determine whether this phenomenon exists in larger animals and humans.

Keywords: cytokines, learning and memory, living environment, neuroinflammation, mice, surgery

Introduction

Caregiving spouses of patients with dementia have an increased chance to suffer from dementia (Norton, Smith, Ostbye, et al., 2010). Although the mechanism for this phenomenon is not clear, factors, such as similar living environment and increased stress due to caregiving to the patients, are thought to contribute to the development of dementia in the caregiving spouses (Norton, et al., 2010; Vitaliano, Zhang, Scanlan, 2003). It has been difficult to study the molecular mechanism for this phenomenon because of the lack of an animal model for it.

More than 20 million Americans receive surgery each year. Post-operative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) is a documented clinical phenomenon that has been attracting significant attention from the public and professionals in recent years (Moller, Cluitmans, Rasmussen, et al., 1998; Monk, Weldon, Garvan, et al., 2008; Newman, Kirchner, Phillips-Bute, et al., 2001). POCD is characterized by decline of learning and memory after surgery and can occur in 10 to 40% of patients (Moller, et al., 1998; Monk, et al., 2008; Newman, et al., 2001). POCD can be associated with increased mortality (Monk, et al., 2008; Steinmetz, Christensen, Lund, et al., 2009). We and others have shown that neuroinflammation may be the underlying pathophysiology for the cognitive impairment after anesthesia and surgery in animals (Cao, Li, Lin, et al., 2012; Cibelli, Fidalgo, Terrando, et al., 2010). Although the role of neuroinflammation in POCD in humans has not been firmly established, surgery can induce neuroinflammation in humans (Tang, Baranov, Hammond, et al., 2011). Unlike the situation in caregiving spouses of patients with dementia, it is not known yet whether living with a patient with surgery will have a negative effect on one’s cognition. We hypothesize that living with subjects after surgery induces learning and memory dysfunction. As an initial step to test this hypothesis in animals, we determined the learning and memory function of mice that were cage-mates with mice that had surgery. In addition, we determined whether there was inflammatory response in the brain of cage-mates and if so, whether this inflammatory response played a role in their learning and memory dysfunction. For this purpose, we used pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC), an anti-inflammatory agent (Zhang, Jiang, Zuo, 2014).

Materials and methods

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, VA) had approved our animal protocol. All animal studies were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication number 80-23) revised in 2011.

Animal Groups

Six to eight-week old male CD-1 mice were from Charles River Laboratories International (Wilmington, MA). They were housed 5 mice per cage when they were shipped to us. They were housed in this way for at least 7 days before 2 mice from each cage were randomly selected to have right common carotid arterial exposure. After surgery, they were placed back in the same cage with the other 3 mice. These 3 mice without surgery were called cage-mates. These cage-mates were randomly assigned to three groups: (1) cage-mates, (2) cage-mates that received intraperitoneal injection of normal saline (NS) once every day for three days with the first injection at the time when the other 2 mice were having surgery, and (3) cage-mates that received intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg PDTC once every day for 3 days with the first injection at the time when the other 2 mice were having surgery. PDTC was dissolved freshly in NS before each use. This PDTC dose (50 mg/kg) was selected based on previous studies (Gui, Lei, Zuo, 2017; Yang, Sun, Ma, et al., 2017; Zhang, Tan, Jiang, et al., 2014) and did not affect learning, memory, microglial activation and proinflammatory cytokine production of control rodents in our previous studies (Gui, et al., 2017; Zhang, Jiang, Zuo, 2014). In addition to these three cage-mate groups, the two groups, surgery group and control group, were included in the study. The mice in surgery group are those mice that had surgery and lived with the non-surgery cage-mates. The control mice were not exposed to anesthesia and surgery and were handled in the same way as cage-mates, such as being removed from the vivarium, but without exposure to mice that had surgery. Each lot of mice (each lot represented one purchase of animals) was randomly assigned to control, surgery or cage-mate groups. Six lots of mice were used to generate the data in figure 1. These five groups of mice were studied to determine the effects of cage-sharing with surgery mice on the learning and memory of the cage-mates. The inclusion of the comparison between surgery group and control group was to have a positive control in the study as surgery is known to induce learning and memory dysfunction (Zhang, et al., 2014; Zhang, Tan, Jiang, et al., 2015). Additional groups of mice that were subjected to the various experimental conditions as described above but without behavior testing were used for harvesting brain tissues to measure cytokines.

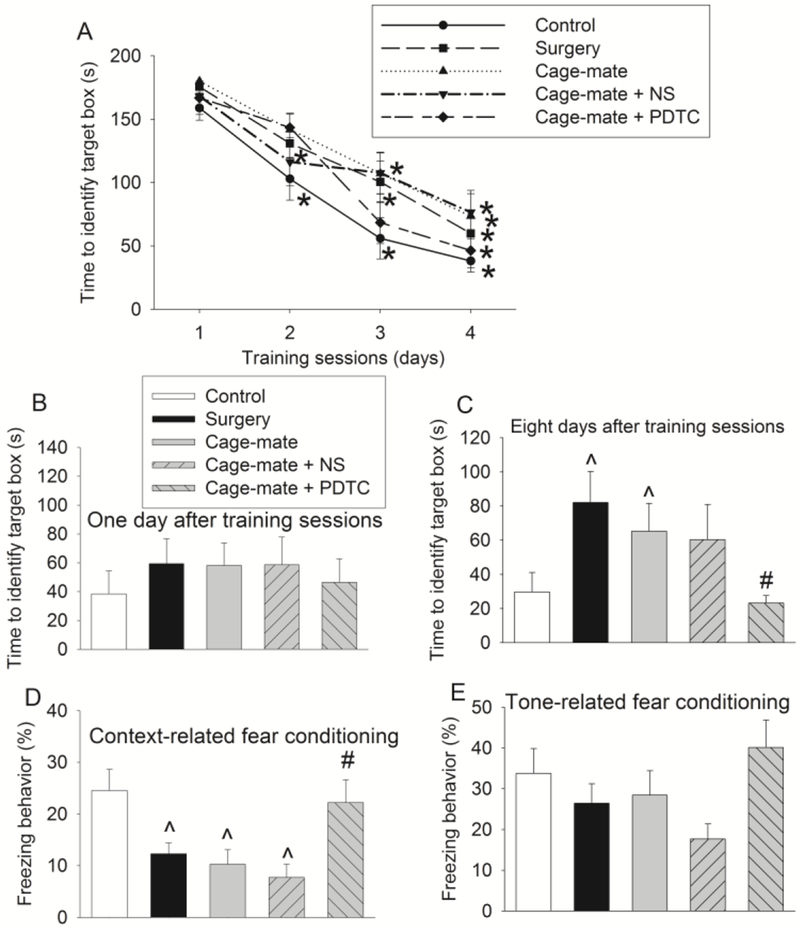

Fig. 1.

Surgery and cage-sharing with surgery mice impair learning and memory. Six to eight week old CD-1 male mice were subjected to right common carotid arterial exposure under isoflurane anesthesia (surgery group). Some cage-mates received intraperitoneal injection of normal saline or 50 mg/kg/day PDTC for three days with the first dose given when the mice in the surgery group were having surgery. Mice were subjected to Barnes maze and fear conditioning from 5 days after the surgery. A: Training sessions of Barnes maze. B and C: One day or eight days after the training sessions of Barnes maze. D: Context-related fear conditioning. E: Tone-related fear conditioning. Results are means ± S.E.M. (n = 11 − 15). * P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding data on day 1 of the same group of mice. ^ P < 0.05 compared with control group. # P < 0.05 compared with cage-mate group.

All mice had standard 12 h light cycle with light from 7 am to 7 pm. They were fed a regular mouse diet (Harland Laboratories, Dublin, VA) provided by the vivarium. They were housed in regular mouse cages of about 30 cm x 20 cm x 16 cm.

Anesthesia and Surgery

Right common carotid arterial exposure was performed as we described before (Fan, Li, Zheng, et al., 2016). All mice were subjected to surgery between 9 am and 3 pm. Briefly, mice were anesthetized by 1.8% isoflurane. The anesthetic concentrations were monitored with a Datex™ infrared analyzer (Capnomac, Helsinki, Finland). A midline neck incision at about 1.5-cm was made after the mouse was exposed to isoflurane at least for 30 min. The soft tissues over the trachea were retracted gently. One centimeter long right common carotid artery was dissected carefully free from adjacent tissues without injuring vagus nerve. The wound was then irrigated and closed by using surgical suture. The surgical procedure was performed under sterile conditions and lasted around 15 min. After the surgery, all animals received a subcutaneous injection of 3 mg/kg bupivacaine. The total duration of anesthesia was 2 h, a clinically relevant duration of anesthesia. Rectal temperature during anesthesia was monitored and maintained at 37°C with the aid of servo-controlled warming blanket (TCAT-2LV, Physitemp instruments, Clifton, NJ). Mouse’s heart rate and pulse oxygen saturation were monitored continuously by MouseOX Murine Plus Oximeter System (Starr Life Sciences Corporation, Oakmont, PA). After the completion of 2-h anesthesia, each mouse was placed singularly in a regular mouse cage for about 5 min for the mouse to wake up from anesthesia. Once the mouse was able to walk it was then placed back in the original cage where the mouse was housed before the surgery. The mouse was housed in this cage with the other 3 non-surgery mice and another surgery mouse until the end of the experiments. These cages allowed free exchange for air.

Barnes Maze

Five days after surgery or at equivalent time for other non-surgery groups, mice were subjected to Barnes maze as we previously described (Fan, et al., 2016) to test their spatial learning and memory. First, mice were placed in the middle of a circular platform that had 20 equally spaced holes (SD Instruments, San Diego, CA). Among these holes, one was connected to a dark chamber named target box. Mice were encouraged to find the target box by aversive noise (85 dB) and bright light (200 W) shed on the platform. They had a spatial acquisition phase that lasted for 4 days with 3 min per trial, 2 trials per day and 15 min between each trial. Then, mice were subjected to the reference memory tests on day 5 (short-term retention) and on day 12 (long-term retention). They were not subjected to any tests or handling from day 5 to day 12. The latency to find the target box during each trial was recorded and analyzed with the assistance of ANY-Maze video tracking system (SD Instruments, San Diego, CA).

Fear Conditioning

One day after Barnes maze test, mice were subjected to a fear conditioning test as we previously described (Fan, et al., 2016). Each mouse was placed into a test chamber wiped with 70% alcohol and exposed to 3 tone-foot shock pairings (tone: 2000 Hz, 85db, 30 s; foot shock: 0.7 mA, 2 s) with an interval 1 min in a relatively dark room. The mouse was removed from this test chamber 30 s after the conditioning stimuli. The animal was placed back in the same chamber without the tone and shock 24 h later for 6 min. The animal was placed 2 h later into another test chamber that had different context and smell from the first test chamber in a relatively well-lit room. The second chamber was cleaned with 1% acetic acid. Freezing behavior was recorded for 3 min without the tone stimulus. The tone was then turned on for 3 cycles, each cycle for 30 s followed by 1-min inter-cycle interval (4.5 min in total). Animal activity in these two chambers was video-recorded. The freezing behavior in the 6 min in the first chamber (context-related) and 4.5 min in the second chamber (tone-related) was scored in a 6 s interval by an observer who was blind to the group assignment.

Brain Tissue Harvest

Mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane for 2 min and perfused transcardially with NS at 1 day or 5 days after anesthesia and surgery. Their cerebral cortex and hippocampus were dissected out immediately for ELISA assay.

Quantification of Interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6

Brain tissues were homogenized on ice in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.3) containing protease inhibitors (10 mg/ml aproteinin, 5 mg/ml peptastin, 5 mg/ml leupeptin, and 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride). Homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was then ultra-centrifuged at 150,000 g for 2 h at 4°C. The supernatant of each sample after this ultra-centrifugation was assessed by Bradford protein assay. ELISA kits for measuring IL-1β (catalog number: MLB00C; R&D Systems) and IL-6 (catalog number: M6000B; R&D Systems) were used to quantify their content in the samples according to the manufacturer’s instructions as we described before (Zhang, et al., 2014; Zhang, et al., 2015). The quantity of IL-1β and IL-6 in each brain sample was standardized to the protein contents.

Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed parametric data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. (n > 7). One-way or two-way repeated measures analysis of variance followed by Tukey test was used to analyze the data from the training sessions of Barnes maze test within the same group or between groups, respectively. Other data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by the Tukey test if the data were normally distributed or by one-way analysis of variance on ranks followed by the Tukey test if the data were non-normally distributed. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05 based on two-tailed hypothesis testing. SigmaStat (Systat Software, Inc., Point Richmond, CA, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results and Discussion

To test whether living with subjects that have surgery will negatively affect one’s learning and memory, we housed 5 CD-1 male mice per cage. Among them, 2 mice had right common carotid arterial exposure (surgery) and 3 mice had no surgery. They were subjected to Barnes maze and fear conditioning tests starting 5 days after the surgery. Mice took less time to identify the target box with more training in the Barnes maze test. The time to identify the target box on training day 4 for mice in all groups was shorter than that on training day 1 (Fig. 1). Surgery and living with the mice that had surgery (cage-mates) were significant factors to influence the time to identify the target box during training sessions by two-way repeated measures analysis of variance [F(1,28) = 4.777, P = 0.037 and F(1,28) = 6.721, P = 0.015, respectively) (Fig. 1A). The influence of training session numbers on the time to identify the target box was significant in both analyses [F(3,28) = 46.436, P < 0.001 and F(3,28) = 44.830, P < 0.001, respectively, in the analyses for identifying surgery and cage-sharing as significant factors). However, there were no interactions between surgery and training session numbers or cage-sharing and training session numbers [F(3,28) = 0.650, P = 0.585 and F(3,28) = 0.694, P = 0.558, respectively). These data suggest that the overall significant effect of surgery and cage-sharing on the time to identify the target box does not depend on the number of training sessions. The cage-sharing effect on the time to identify the target box was attenuated by PDTC [F(1,24) = 1.533, P = 0.228 compared with control group]. PDTC is often used as an anti-inflammatory agent (Liu, Ye, Malik, 1999; Yang, et al., 2017; Zhang, et al., 2014). This effect is considered to be mediated by inhibition of nuclear factor (NF)-κB, a transcription factor that is critical for the production of pro-inflammatory mediators (Gui, et al., 2017; Liu, Ye, Malik, 1999; Zhang, et al., 2014). There was a significant difference among the groups in the mean values of the time to identify the target box on day 8 after the training sessions [F(4,62) = 2.577, P = 0.046]. Similar to the data of training sessions, mice with surgery and their cage-mates required longer time to identify the target box than control mice on day 8 after the training sessions. PDTC but not NS reduced the time for the cage-mates to identify the target box. There was a significant difference among the groups in the mean values of context-related freezing behavior [F(4,62) = 5.093, P = 0.001]. Mice with surgery and their cage-mates had reduced context-related fear conditioning than control mice and PDTC but not NS abolished the reduction of fear conditioning behavior in cage-mates. Similar patterns of changes occurred with tone-related fear conditioning but the changes did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1). These results suggest surgery induces learning and memory dysfunction, which is consistent with what has been shown previously (Fan, et al., 2016; Zheng, Lai, Li, et al., 2017). Interestingly, our results also suggest that cage-mates of the mice with surgery develop learning and memory dysfunction. This dysfunction can be attenuated by PDTC. PDTC at the dose used in this study does not affect learning, memory and proinflammatory cytokine levels in the brain of rodents under control condition in our previous studies (Gui, et al., 2017; Zhang, et al., 2014). Thus, the findings from our current study suggest a role of inflammation in the learning and memory dysfunction of cage-mates.

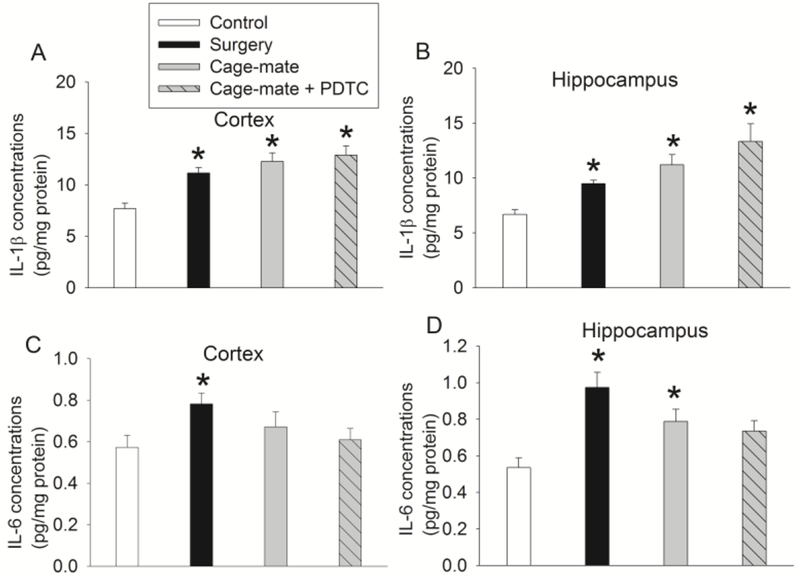

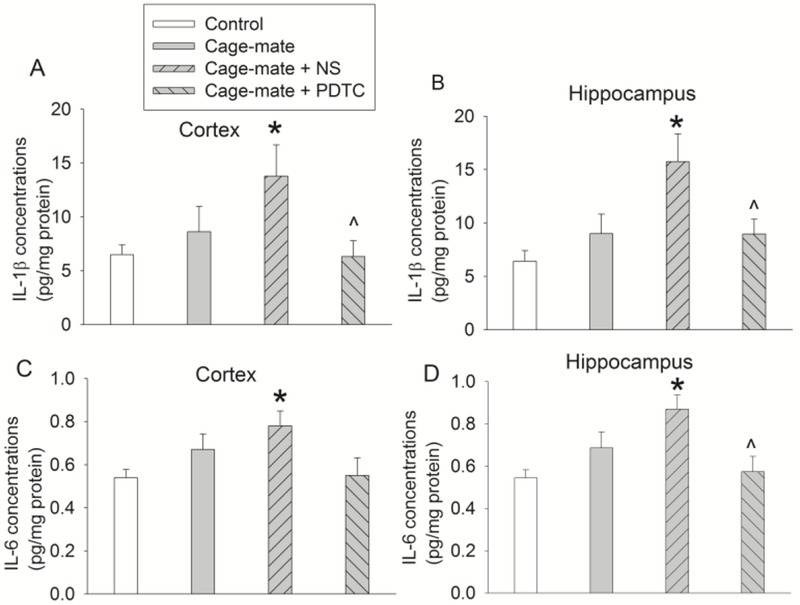

Since neuroinflammation appears to play a role in POCD (Zhang, et al., 2014; Zhang, et al., 2014; Zheng, et al., 2017), we determine whether cage-mates have neuroinflammation. There was a significant difference among the groups in the mean values of IL-1β and IL-6 in the brain one day after surgery [F(3,24) = 10.424, P < 0.001 for IL-1β in the cortex; F(3,24) = 8.456, P < 0.001 for IL-1β in the hippocampus; F(3,24) = 3.390, P = 0.034 for IL-6 in the cortex; F(3,24) = 7.377, P = 0.001 for IL-6 in the hippocampus]. Consistent with our previous findings (Zhang, et al., 2014; Zhang, et al., 2014; Zheng, et al., 2017), the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-6 were increased in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus one day after surgery, suggesting that surgery increases proinflammatory cytokines. The levels of IL-1β and IL-6 were also increased in the brain of cage-mates after they had been with surgery mice for one day. Surprisingly, PDTC did not inhibit the increase of IL-1β and IL-6 at this time point (Fig. 2), possibly because only one dose of PDTC was given by that time, which did not achieve the effectiveness of anti-inflammation in the brain. There was a significant difference among the groups in the mean values of IL-1β and IL-6 in the brain at the time corresponding to 5 days after surgery [F(3,24) = 3.449, P = 0.032 for IL-1β in the cortex; F(3,24) = 4.902, P = 0.009 for IL-1β in the hippocampus; F(3,24) = 3.180, P = 0.042 for IL-6 in the cortex; F(3,24) = 5.147, P = 0.007 for IL-6 in the hippocampus]. Interestingly, cage-mates receiving injections of NS had a significant increase of IL-1β and IL-6 in their brain at 5 days after they had been cage-mates with surgery mice. This increase was inhibited by PDTC (Fig. 3). These results suggest that similar to mice with surgery, cage-mates have increased proinflammatory cytokines in the brain. This increase can be lengthened by intraperitoneal injection (once every day for 3 days). This response is to our surprise and has not been reported. Nevertheless, this lengthened proinflammatory response is attenuated by PDTC. Of note, we and others have shown that neuroinflammation after peripheral surgery disappeared by 5 days after surgery (Cibelli, et al., 2010; Zhang, et al., 2014; Zhang, et al., 2014), which is similar to the finding that cage-mates did not have increased IL-1β and IL-6 in their brain by this time in this current study. Neuroinflammation may lead to decreased growth factors, which results in reduced neurogenesis or other downstream events for the development of cognitive dysfunction at a delayed phase (Fan, et al., 2016; Gui, et al., 2017).

Fig. 2.

Proinflammatory cytokine level one day after surgery. Mice were subjected to the conditions as described in figure 1. Their brain was harvested for measurement of cytokines one day after surgery. Results are means ± S.E.M. (n = 7). * P < 0.05 compared with control group.

Fig. 3.

Proinflammatory cytokine levels five days after sharing cages with mice that had surgery and anesthesia. Mice were subjected to the conditions as described in figure 1. Results are means ± S.E.M. (n = 7). * P < 0.05 compared with control group. ^ P < 0.05 compared with cage-mate plus NS group.

Our study has provided initial evidence that cage-mates of surgery mice develop learning and memory dysfunction. Contagiousness or empathic transfer of pain and itch behavior has been reported in mice (Langford, Crager, Shehzad, et al., 2006; Yu, Barry, Hao, et al., 2017). These phenomena in mice may likely be due to emotional contagion (Sivaselvachandran, Acland, Abdallah, et al., 2018) and depend on the familiarity and status of the animals (Gonzalez-Liencres, Juckel, Tas, et al., 2014; Ueno, Suemitsu, Murakami, et al., 2018). Empathic behaviors are easy to induce among cage-mates that are familiar with each other. (Gonzalez-Liencres, et al., 2014; Langford, et al., 2006). Various molecules, such as gastrin-releasing peptide and oxytocin, may be involved in the contagious or empathic behaviors (Laviola, Zoratto, Ingiosi, et al., 2017; Yu, et al., 2017). Interestingly, mice with reduced empathic behaviors have impaired sociability and emotional memory (Laviola, et al., 2017). It is unclear whether our finding on cage-mates of surgery mice represents another form of contagiousness or empathic transfer of mouse behavior and neuropathological process or is simply due to the stress in these cage-mates.

Our finding on cage-mates is significant because it suggests that complex behavior, such as learning and memory, of these cage-mates of surgery mice is affected and this effect is for a long time. However, additional studies are needed to determine whether this phenomenon is reproducible in other stress or pain animal models. Also, it is not appropriate to extrapolate our findings in mice to humans.

In summary, we found that cage-mates of mice with surgery increased proinflammatory cytokines in the brain and developed impairment of learning and memory. Proinflammatory response in the brain may contribute to the cognitive impairment in the cage-mates. Future basic science studies are needed to investigate how neuroinflammation and the dysfunction of learning and memory occur in the cage-mates of mice with surgery.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from Commonwealth of Virginia Alzheimer’s and Related Diseases Research Award Fund, Richmond, VA, grants (RF1AG061047 and R01HD089999 to Z Zuo) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and the Robert M. Epstein Professorship endowment, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Cao L, Li L, Lin D & Zuo Z. (2012). Isoflurane induces learning impairment that is mediated by interleukin lbeta in rodents. PLoS ONE, 7, e51431 10.1371/joumal.pone.0051431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cibelli M, Fidalgo AR, Terrando N, Ma D, Monaco C, Feldmann M, …Maze M. (2010). Role of interleukin-1beta in postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Ann Neurol, 68, 360–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan D, Li J, Zheng B, Hua L & Zuo Z. (2016). Enriched Environment Attenuates Surgery-Induced Impairment of Learning, Memory, and Neurogenesis Possibly by Preserving BDNF Expression. Mol Neurobiol, 53, 344–354. 10.1007/s12035-014-9013-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez-Liencres C, Juckel G, Tas C, Friebe A & Brune M. (2014). Emotional contagion in mice: the role of familiarity. Behav Brain Res, 263, 16–21. 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gui L, Lei X & Zuo Z. (2017). Decrease of glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor contributes to anesthesia- and surgery-induced learning and memory dysfunction in neonatal rats. J Mol Med (Berl), 95, 369–379. 10.1007/s00109-017-1521-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langford DJ, Crager SE, Shehzad Z, Smith SB, Sotocinal SG, Levenstadt JS, …Mogil JS. (2006). Social modulation of pain as evidence for empathy in mice. Science, 312, 1967–1970. 10.1126/science.1128322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laviola G, Zoratto F, Ingiosi D, Canto V, Huzard D, Fiore M & Macri S. (2017). Low empathy-like behaviour in male mice associates with impaired sociability, emotional memory, physiological stress reactivity and variations in neurobiological regulations. PLoS ONE, 12, e0188907 10.1371/joumal.pone.0188907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu SF, Ye X & Malik AB. (1999). Inhibition of NF-kappaB activation by pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate prevents In vivo expression of proinflammatory genes. Circulation, 100, 1330–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moller JT, Cluitmans P, Rasmussen LS, Houx P, Rasmussen H, Canet J, … Gravenstein JS. (1998). Long-term postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the elderly ISPOCD1 study. ISPOCD investigators. International Study of Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction. Lancet, 351, 857–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monk TG, Weldon BC, Garvan CW, Dede DE, van der Aa MT, Heilman KM & Gravenstein JS. (2008). Predictors of cognitive dysfunction after major noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology, 108, 18–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newman MF, Kirchner JL, Phillips-Bute B, Gaver V, Grocott H, Jones RH, Blumenthal JA. (2001). Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive function after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med, 344, 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norton MC, Smith KR, Ostbye T, Tschanz JT, Corcoran C, Schwartz S, Welsh-Bohmer KA. (2010). Greater risk of dementia when spouse has dementia? The Cache County study. J Amer Geriatr Soc, 58, 895–900. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02806.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sivaselvachandran S, Acland EL, Abdallah S & Martin LJ. (2018). Behavioral and mechanistic insight into rodent empathy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 91, 130–137. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinmetz J, Christensen KB, Lund T, Lohse N & Rasmussen LS. (2009). Long-term consequences of postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Anesthesiology, 110, 548–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang JX, Baranov D, Hammond M, Shaw LM, Eckenhoff MF & Eckenhoff RG. (2011). Human Alzheimer and inflammation biomarkers after anesthesia and surgery. Anesthesiology, 115, 727–732. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31822e9306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ueno H, Suemitsu S, Murakami S, Kitamura N, Wani K, Okamoto M, Ishihara T. (2018). Empathic behavior according to the state of others in mice. Brain Behav, 8, e00986 10.1002/brb3.986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vitaliano PP, Zhang J & Scanlan JM. (2003). Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psycholl Bull, 129, 946–972. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang H, Sun R, Ma N, Liu Q, Sun X, Zi P, … ,Yu L (2017). Inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB signal by pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Oncotarget, 8, 47296–47304. 10.18632/oncotarget.17624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu YQ, Barry DM, Hao Y, Liu XT & Chen ZF. (2017). Molecular and neural basis of contagious itch behavior in mice. Science, 355, 1072–1076. 10.1126/science.aak9748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J, Jiang W & Zuo Z. (2014). Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate attenuates surgery-induced neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction possibly via inhibition of nuclear factor kappaB. Neurosci, 261, 1–10. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Tan H, Jiang W & Zuo Z. (2014). Amantadine alleviates postoperative cognitive dysfunction possibly by increasing glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in rats. Anesthesiology, 121, 773–785. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Tan H, Jiang W & Zuo Z. (2015). The choice of general anesthetics may not affect neuroinflammation and impairment of learning and memory after surgery in elderly rats. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol, 10, 179–189. 10.1007/s11481-014-9580-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng B, Lai R, Li J & Zuo Z. (2017). Critical role of P2X7 receptors in the neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction after surgery. Brain Behav Immun, 61, 365–374. 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]