On average, adolescent cessation apps included more adherence content and adolescent-specific content than general apps.

Keywords: Smoking cessation, Adolescent smoking cessation, Mobile health, mHealth

Abstract

Adolescent cigarette smokers have an increased risk of sustained smoking into adulthood. Smartphone applications (apps) for smoking cessation are a promising treatment resource. However, research on apps for adolescent smoking cessation is limited. This study compared smoking cessation mobile apps targeting an adolescent audience with popular cessation apps for a general audience. Adolescent and general-audience apps were identified by searching the Google Play and Apple App Stores (November 2016). Two coders assessed each app for adherence to clinical practice guidelines for tobacco and adolescent-specific content (2016–2017) and developed a summary score that summed all adherence and adolescent content criteria. Eight adolescent apps were identified and compared with the top 38 general apps (as ranked by Apple and Google). Both general and adolescent apps commonly had adherence content related to developing a quit plan (general: 73.68 per cent; adolescent: 87.50 per cent) and enhancing motivation by describing the rewards of not smoking (general: 76.32 per cent; adolescent: 62.50 per cent). Adolescent-specific content such as peer influence on smoking was common in adolescent apps but not in general apps (general: 5.26 per cent; adolescent: 62.50 per cent). Adolescent apps had a higher general adherence content summary score [t (44) = 2.55, p = .01] and a higher adolescent content summary score [t (7.81) = 2.47, p = .04] than the general apps. On average, adolescent cessation apps included more adherence content and adolescent-specific content than general apps. Future research is needed to determine the extent to which adolescents engage with the adherence content available in these apps.

Implications

Practice: Smartphone applications designed to assist with smoking cessation are available in the Google Play and Apple App Stores; apps that were designed specifically for adolescents include more adherence content than apps designed for a general population.

Policy: Policymakers who want to promote smoking cessation among adults and adolescents should support assessing the efficacy of these apps as well as what features make adolescents more likely to download and use popular apps.

Research: Future research should assess how adolescents engage with smoking cessation apps.

INTRODUCTION

Adolescents who smoke cigarettes have an increased risk of sustained smoking into adulthood [1]. Moreover, 90 per cent of smokers start smoking cigarettes before age 18, and data from 2012 indicate that each day, approximately 2,100 youth become daily smokers [2]. Although cigarette smoking has declined among adolescents, in 2014, approximately 9.3 per cent of high school students reported smoking cigarettes within the past 30 days [3]. About half of adolescent smokers are interested in quitting and have made a quit attempt in the past year [4]. However, most quit attempts are unsuccessful; only 12.2 per cent of high school students who smoke daily and attempt to quit maintain abstinence, comparable to rates among adult populations [5, 6].

Given low cessation rates among adolescents, it is crucial to develop interventions that help young people quit smoking. Clinical practice guidelines emphasize behavioral treatments as a method for addressing tobacco use among youth. Although there are a number of evidence-based behavioral treatments for adolescents, these interventions are often limited in reach and scalability, as they typically require in-person attendance [7, 8]. In addition, many adolescents are reluctant to try in-person treatment as it may mean risking their confidentiality.

Furthermore, adolescents have unique motivations to quit smoking. Research indicates that adolescents are more responsive to short-term than to long-term health consequences of smoking [9]. There is evidence that exposing adolescents to short-term consequences (e.g., physical unattractiveness, bad breath, or decreased ability to play sports) reduces smoking [10] and increases readiness to quit smoking [11]. Short-term consequences of smoking may also promote enrollment in cessation programs [12]. The adolescent tobacco use literature also emphasizes the importance of peer influences [13, 14], the addictiveness of cigarettes as it relates to continued use into adulthood [15], and adolescent-specific triggers (e.g., school-related stressors) [16, 17] as factors that impede cessation. Altogether, the unique challenges for adolescent smokers underscore the need for additional research on adolescent-focused cessation treatments.

Interest in phone-based behavioral interventions for adolescents has increased [18]. As of 2015, approximately 75 per cent of adolescents own or have access to a smartphone, and 94 per cent browse the Web via a mobile device daily [19]. Moreover, a recent, nationally representative survey found that almost two-thirds of adolescents and young adults reported having used a health-related mobile application [20]. Smartphone applications have the potential to reach large teen audiences [21] and are both scaleable and cost-effective. Additionally, smartphone apps may address users’ concerns about participant confidentiality because adolescents can use such programs from the privacy of a mobile device [22].

In a small but growing literature, previous studies have characterized the smoking cessation app environment by documenting the number of apps available and conducting content analyses to assess for the presence of content informed by the scientific literature [23–27]. Data from 2012 indicated that there are over 400 smartphone apps for smoking cessation in Android and Apple App Stores [23]. Research also suggests that few apps available are informed by empirical literature [23, 25, 26]. These studies assessed apps for elements of clinical practice guidelines (e.g., Assist with Quit Plan), the 5A’S (ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange follow-up), and behavior change techniques such as asking about the use of stop-smoking medications [23, 24, 26]. Another study assessed smartphone apps for smoking cessation by examining the number of apps with scientific support based on published studies [28] and found only three apps with scientific support available in the app store. Taken together, these studies suggest that there is a need for apps that include techniques informed by science. Additionally, neither the study by Haskins and colleagues (2017) nor a recent systematic review on all tobacco cessation interventions developed for young adults and adolescents [29] identified published literature on smartphone apps specifically for adolescent smoking cessation. There is a gap in the empirical literature that addresses how smartphone apps incorporate content tailored to adolescents, such as the short-term consequences of smoking or peer influences on smoking [10–12].

This study aimed to compare smoking cessation apps advertised for adolescents currently available in the Google Play and iTunes Stores to a comparison group of popular general-audience cessation apps. The focus of this study was adolescent apps, so all available adolescent apps were compared with a sample of general apps. Apps were compared in terms of incorporation of U.S. Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence guidelines, measured by “adherence content,” and the extent to which these apps are designed specifically for young smokers, measured by “adolescent-specific content.” Finally, adolescent apps were also compared with the sample of general apps with regards to app characteristics, engagement, and technical features.

METHODS

Identifying smartphone apps

Two types of smoking cessation apps were assessed in this study: apps tailored to adolescents (here referred to as adolescent apps) and the top performing general-audience apps (here referred to as general apps). Because the focus of this study was understanding and characterizing adolescent apps specifically, all available adolescent apps that met inclusion criteria were assessed as part of this study. A set of popular general apps were selected as a comparison group to investigate the ways in which adolescent apps differ from general apps in terms of adherence content and adolescent-specific content. Adolescent apps were searched for on November 9, 2016, and general apps were searched for on November 10, 2016. This study was limited to apps that were available for free in the Google Play and Apple App Stores. Limiting the study to free apps was based on research indicating that adolescents often choose free and/or inexpensive options on their smartphone devices [30]. The app inclusion criteria were designed to ensure that the researchers would assess apps that a user would be likely to use—including only using free apps and prioritizing general apps by popularity.

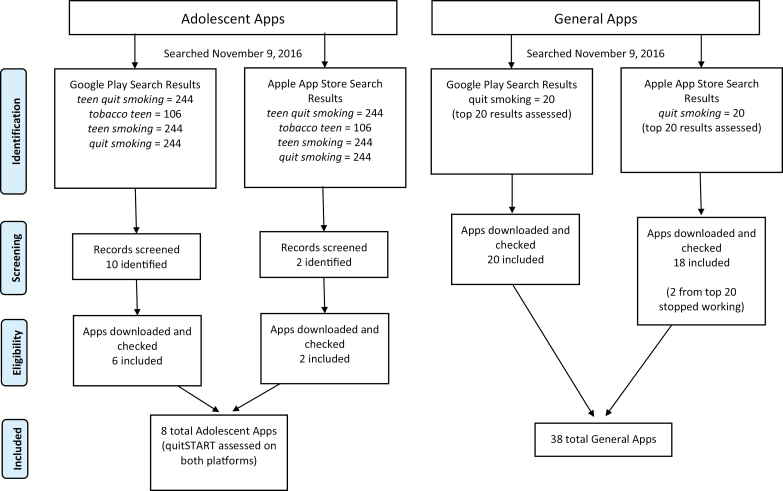

App search terms were informed by previous research studies that identified general apps by searching terms such as quit smoking [24, 26]. To search adolescent-specific apps, the following search terms were used in the Google Play and Apple App Stores: teen quit smoking, tobacco teen, teen smoking, and quit smoking. The term quit smoking was included without a teen qualifier to ensure that no additional apps were revealed in a general search for quitting smoking. In the Google Play Store, this search resulted in the following: teen quit smoking = 244 apps, tobacco teen = 106 apps, teen smoking = 244 apps, and quit smoking = 244 apps (Fig. 1). The first author, C.D.R., examined the apps to determine whether they met the following inclusion criteria: (a) included content related to quitting cigarette smoking and (b) included the word adolescent (or a synonym such as teen) in the description or were categorized as teen in the Google Play Store. In the Google Play Store, 10 apps were identified that met these inclusion criteria. The same researcher, C.D.R., then downloaded the apps to verify the inclusion criteria. A total of six apps were included from the Google Play Store (Table 1).

Fig. 1 |.

App search strategy.

Table 1.

| Google Play Apps (listed in ascending order of adolescent-specific content)

| App Name | Category | App Developer | Reviews | Rating | Adherence General | Adolescent- Specific | Downloads |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quit Smoking— Smokerstop | General | Titus J. Brinker | 2,217 | 4.5 | 7 | 0 | 5 |

| Qwit | General | Team Geny | 9,018 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 6 |

| Quit Smoking Now: Quit Buddy! | General | HQmedia | 1,062 | 4.1 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| I Give Up Smoking | General | BamyaSoft | 400 | 4.4 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| Get Rich or Die Smoking | General | Tobias Gruber | 11,337 | 4.6 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| Drop it! Quit Smoking | Adolescent | Nikola Mladenovic | 352 | 4.6 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Quit Smoking | General | HC | 2,206 | 4.7 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Quit Smoking Cigarettes | Adolescent | Best App Made with Love | 10 | 3.4 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Quit smoking day counter | General | mindsaver.ru | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Quit Smoking | General | NP Sites | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Smoke Free | General | David Crane | 15,085 | 4.6 | 7 | 1 | 5 |

| Stop Smoking In 2 Hours | General | Juice Master | 453 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Stop Smoking— EasyQuit Free | General | Mario Hanna | 189 | 4.7 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Quit Tracker: Stop Smoking | General | despDev | 3,144 | 4.5 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| MyQuitTime—Stop Smoking | General | Arete Appware | 206 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Quit Smoking | General | The Game Lab | 127 | 4.4 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Stop Smoking Hypnosis | General | On Beat Limit | 529 | 3.7 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Quit Smoking 2017—Breathe | General | Cddevelopment | 5,674 | 4.4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| How to Stop Smoking Now | Adolescent | Nicholas Gabriel | 11 | 3.5 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| Quit Smoking: Cessation Nation | General | Ron Horner | 5,921 | 4.5 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Quit Now | Adolescent | Fewlaps | 28,003 | 4.2 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| Quit Smoking | General | Mastersoft Ltd | 3,606 | 4.3 | 4 | 2 | 5 |

| Quit Smoking Helper | General | Parobin Apps | 7 | 4.3 | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| This is Quitting | Adolescent | Schroeder Garage | 30 | 4.6 | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| Quit Smoking in 28 Days Audio | General | Pitashi | 7 | 4.4 | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| quitStart | Adolescent | ICF International | 109 | 3.6 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

Categories for Downloads are as follows: 1 = 1,000–5,000; 2 = 5,000–10,000; 3 =10,000–50,000; 4 = 50,000–100,000; 5 = 100,000–500,000; 6 = 500,000–1,000,000; 7 = 1,000,000–5,000,000.

A similar procedure was used to identify adolescent apps in the Apple App Store. This study utilized the same search terms as above and found: teen quit smoking = 5 apps, tobacco teen = 7 apps, teen smoking = 4 apps, and quit smoking = 100 apps (Fig. 1). Using the same inclusion criteria and procedures described above, two apps were identified. Although quitSTART was previously identified in the Google Play Store, the Apple App Store version was coded separately. The research team did not assume apps to be the same across platforms.

General apps were defined as apps that did not specifically target adolescents and were among the first 20 apps to appear in the Google Play Store or Apple App Store using the search term “quit smoking.” Although the ranking algorithm is unavailable to the public, research suggests that factors such as a high-download volume and continuous quality updates contribute to the presence of apps in top rankings [31]. The study was restricted to the first 20 apps displayed in each store because, as noted in previous app content analyses, users rarely go beyond the first 1–2 screens in app stores [32], and conducting an exhaustive search of general apps was beyond the scope of this study. The current study only required a sample of general apps to serve as comparison for adolescent apps. Two general apps in the Apple App Store that stopped working before coding was completed were removed from the analyses. The final number of adolescent and general apps was 46 (38 general and 8 adolescent).

Coding procedure

The app characteristics section of the coding guide was informed by a previous study of smoking cessation apps for the general population [23]. For app characteristics, the study research team collected descriptive data about the apps including the number of reviews provided by users, ratings provided by users, number of downloads, and main app functions. Ratings were provided by users on a five-point scale with higher scores representing more favorable ratings. The main functions of the app were assigned codes by the research team, including (a) Tracker, (b) Calculator, (c) Hypnosis, and (d) Game (Supplementary Table 1). These categories were not mutually exclusive. For example, an app such as Smoke Free was coded as including a tracker because it tracked the amount of time a smoker was abstinent, cigarettes not smoked, and cravings resisted. It was also coded as a calculator because it calculated the amount of money saved by not smoking.

The second section of the coding guide assessed adherence to clinical practice guidelines for tobacco dependence. Consistent with prior studies [23], the adherence criteria were adapted items from the U.S. Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence [33]. Research staff members determined whether the 11 items derived from these guidelines were “present” or “not present.” An adherence content summary score was calculated by summing responses on the 11 items (maximum score = 11) for each app.

The third section of the coding guide assessed smoking cessation content specific to adolescents. These items were developed by the research team and informed by the literature. This study evaluated the presence of content on short-term health consequences of smoking [10, 11], peer influences [13, 14], addiction [15], and adolescent-specific triggers [16, 17]. Two research staff members assessed the adolescent and general apps to determine whether adolescent content was “present” or “not present.” An adolescent content summary score was calculated by adding responses on the four items (maximum score = 4) for each app.

The fourth section of the coding guide assessed engagement and technical features of the app. App features including the presence of social networking communities within the app, customization (e.g., setting a quit date), and sharing on social media were documented.

Apps were coded by trained staff members. Training consisted of staff members independently coding three sample smartphone apps using the scoring coding guide described above. The research team discussed all discrepancies and made clarifications to the scoring guide. The final coding guide was provided to the four staff members, and the 46 apps were coded by two research staff members. The coding process was completed between November 2016 and April 2017. The average inter-rater agreement based on Cohen’s κ ranged from 0.64 to 1 for Apple App store apps. The average inter-rater agreement for Google Play apps ranged from 0.62 to 1. Discrepancies in coding were resolved by research team members reviewing and clarifying scoring criteria. Research staff members initially attempted to resolve discrepancies on their own. Any discrepancies that could not be resolved by two staff members were resolved by a third reviewer.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (e.g., percentages) were used to summarize the presence of app characteristics. The app categories presented in Tables 2 and 3 were dichotomous (“present” vs. “not present”). Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) and independent sample t-tests were calculated to assess differences between adolescent and general apps for the general adherence content summary score and adolescent content summary score. SAS 9.3 was used for analyses. Analyses were conducted April–August 2017.

Table 2 |.

Summary of apps with adherence and adolescent-specific content

| All (n = 46) | General (n = 38) | Adolescent (n = 8) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Adherence Content | |||

| Specific to smoking | 43(93.48%) | 35(92.11%) | 8(100%) |

| Assess willingness to quit | 5(10.87%) | 2(5.26%) | 3(37.50%) |

| Ask for tobacco use status | 3(6.52%) | 2(5.26%) | 1(12.50%) |

| Advise every user to quit | 4(8.70%) | 3(7.89%) | 1(12.50%) |

| Assist with a quit plan: overall | 35(76.09%) | 28(73.68%) | 7(87.50%) |

| Assist with a quit plan: practical counseling | 19(41.30%) | 13(34.21%) | 6(75.00%) |

| Assist with a quit plan: supplementary info | 13(28.26%) | 9(23.68%) | 4(50.00%) |

| Assist with a quit plan: meds | 6(13.04%) | 4(10.53%) | 2(25.00%) |

| Enhance motivation: rewards | 34(73.91%) | 29(76.32%) | 5(62.50%) |

| Enhance motivation: roadblocks | 14(30.34%) | 9(23.68%) | 5(62.50%) |

| Enhance motivation: risks | 8(17.39%) | 5(13.16%) | 3(37.50%) |

| Adolescent-specific Content | |||

| Short-term health consequences of smoking | 18(39.13%) | 14(36.84%) | 4(50.00%) |

| Peer influences on smoking | 7(15.22%) | 2(5.26%) | 5(62.50%) |

| Addiction or brain development | 14(30.43%) | 9(23.68%) | 5(62.50%) |

| Adolescent-specific triggers | 5(10.87%) | 1(2.63%) | 4(50.00%) |

All apps were assessed for the inclusion of criteria from the U.S. Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence and adolescent-specific content (short-term health consequences, peer influences, addiction, and adolescent-specific triggers).

Table 3 |.

Summary scores for general and adolescent content

| All (n = 46) | General (n = 38) | Adolescent (n = 8) | t | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General adherence content summary score (M, SD) | 4.00 (2.09) | 3.65 (1.92) | 5.62 (2.26) | 2.55 | .014 |

| Adolescent-specific content summary content score (M, SD) | .96 (1.17) | .68 (.81) | 2.25 (1.75) | 2.471 | .040 |

Maximum values for General and Adolescent scores were 11 and 4, respectively. Satterthwaite test was used due to unequal variances.

RESULTS

The majority of adolescent apps (75 per cent) were in the Google Play Store. Adolescent apps (22 reviews) had fewer reviews than general apps (170 reviews). The mean rating for adolescent apps was 3.98 (SD = .5) compared with 4.32 (.47) for general apps (Table 4). Across all apps, apps were most commonly downloaded between 100,000 and 500,000 times (30.77 per cent of apps fell into this category). The most common app features were Tracker (78 per cent) and Calculator (67 per cent). See Supplementary Table 1 for the full coding guide and descriptions of all categories.

Table 4 |.

App characteristics

| Characteristics | All Apps (n = 46) | General (n = 38) | Adolescent (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|---|

| App Source | |||

| Apple App Store (n, %) | 20 (43.48%) | 18 (47.37%) | 2 (25.00%) |

| Google Play Store | 26 (56.52%) | 20 (52.63%) | 6 (75.00%) |

| Reviews (median) | 134.00 | 169.50 | 22.00 |

| Rating (mean, SD) | 4.25 (0.49) | 4.32 (0.47) | 3.98 (0.50) |

| Google Play downloads (n, %) | |||

| 1,000–5,000 | 6 (23.08%) | 4 (20.00%) | 2 (33.33%) |

| 5,000–10,000 | 2 (7.69%) | 1 (5.00%) | 1 (16.67%) |

| 10,000–50,000 | 3 (11.54%) | 2 (10.00%) | 1 (16.67%) |

| 50,000–100,000 | 4 (15.38%) | 3 (15.00%) | 1 (16.67%) |

| 100,000–500,000 | 8 (30.77%) | 8 (40.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| 500,000–1,000,000 | 2 (7.69%) | 2 (10.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| 1,000,000–5,000,000 | 1 (3.85%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (16.67%) |

| Main functions (n, %) | |||

| Tracker | 36 (78.26%) | 31 (81.58%) | 5 (62.50%) |

| Calculator | 31 (67.39%) | 27 (71.05%) | 4 (50.00%) |

| Rationing | 7 (15.22%) | 7 (18.42%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Hypnosis | 5 (10.87%) | 5 (13.16%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Game | 1 (2.17%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (12.50%) |

All characteristics assessed for all apps with the exception of Google Play Downloads which was only able to be assessed for apps from the Google Play store (sample sizes are as follows: All = 26; General = 20; Adolescent = 6). Rating scale = 1–5. For “rating,” sample size for all apps = 34; general = 27; adolescent = 7. See Supplementary Table 1 for description of main functions. For “reviews,” the range = 0 to 28,003 for all apps; general = 0 to 15,085; adolescent = 2 to 28,003. For “Main functions,” each app could be coded as more than one category.

Table 2 provides an overview of inclusion of adherence content and adolescent-specific content in teen and general apps. Table 3 provides a statistical comparison of Summary Scores for General and Adolescent Content. Adherence contents such as “assist with quit plan: overall” (general: 73.68 per cent; adolescent: 87.50 per cent) and “enhance motivation: rewards” (general: 76.32 per cent; adolescent: 62.50 per cent) were common. Contents such as “advise every user to quit” (general: 7.89 per cent; adolescent: 12.50 per cent) were less common. Adolescent apps had a significantly higher general adherence content summary score than general apps (p = .01). Adolescent-specific contents such as “peer influences on smoking” (general: 5.26 per cent, adolescent: 62.50 per cent) were more common in apps targeted to adolescents. Adolescent apps also had a significantly greater adolescent-specific content summary score than general apps (p = .04). Tables 1 and 5 present descriptive data for each app as well as the general adherence content summary score and adolescent-specific content summary score.

Table 5 |.

Apple Store Apps (listed in ascending order of adolescent-specific content)

| App Name | Category | App Developer | Reviews | Rating | Adherence General |

Adolescent-specific |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quitbit | General | Quitbit, Inc. | 32 | None | 5 | 0 |

| Quit It Lite—Stop Smoking Today | General | digitalsirup GmbH | 687 | None | 4 | 0 |

| Quit Smoking—QuitNow! | General | Fewlaps | 105 | 4.5 | 3 | 0 |

| My Last Cigarette— Stop Smoking Stay Quit | General | Mastersoft Ltd | 441 | 4.5 | 3 | 0 |

| Kwit—Quit Smoking for Good –Smoking Cessation | General | Kwit | 142 | None | 3 | 0 |

| Quit Smoking Now— Quit Smoking Buddy! | General | sander van der graaff | 11 | None | 3 | 0 |

| Quit Smoking: Learn to Stop Smoking Today! | General | AB Mobile Apps LLC | 2 | None | 3 | 0 |

| Quit Smoking Hypnosis—Stop Addiction | General | Mindifi LLC | 12 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| Quit Smoking Hypnosis | General | Surf City Apps LLC | 77 | None | 1 | 0 |

| Kick the Habit: Quit Smoking | General | IcySpark | 30 | None | 1 | 0 |

| One Less Smoke—Quit Smoking | General | Pattern UI LLC | 17 | 2.5 | 1 | 0 |

| Free Butt Out—Quit Smoke Now and Stop Smoking Forever | General | Ellisapps Inc | 150 | 5 | 7 | 1 |

| Livestrong My Quit | General | Demand Media, Inc. | 4,774 | 4.5 | 6 | 1 |

| Smoke Free | General | David Crane | 1,510 | 4.5 | 5 | 1 |

| JustQuit | General | Bharat Gulati | 9 | None | 3 | 1 |

| Quit Smoking—Stop | General | Dennis Ebbinghaus | 0 | None | 3 | 1 |

| Stop-Tobacco | General | Université de Genève | 0 | None | 8 | 2 |

| Stop Smoking – Personal Stories of Success Quit Now | General | Pitashi! Mobile Imagination | 3 | None | 5 | 2 |

| quitSTART | Adolescent | ICF International | 14 | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| Tobacco Free Teen | Adolescent | MD Anderson Cancer Center | 2 | None | 8 | 4 |

Supplementary Table 2 presents the technical and engagement features of these apps such as an in-app community and quizzes. Across all apps, the most common engagement feature was customization (78.26 per cent). Few apps had technical features such as requiring login (6.52 per cent).

DISCUSSION

Adolescent apps were more likely to incorporate the U.S. Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence, including more adherence content for 10 of 11 categories, relative to the general apps. Additionally, adolescent apps were better designed for young smokers, including more adolescent-specific content across all four categories. Statistical testing of summary scores indicated that these differences were significant.

The higher amount of adherence content found in the adolescent apps compared with the top general apps suggests that adolescents have the potential to receive more cessation tips and tools than adults. However, it is unclear to what extent these apps reach young audiences, given that Google Play does not provide information about app downloads by age or any other demographic characteristics. However, research on adolescents and digital health information seeking has found that the vast majority of adolescents do not search for resources that are explicitly designed for adolescent audiences [34], which suggests that many adolescents are in fact turning to the general-audience interventions with weaker adherence content.

The presence of more adherence content in adolescent apps may be associated with the organization that developed the app. Four adolescent apps were developed by either a university or government entity: (a) quitStart Apple store, (b) Tobacco Free Teen, (c) This is Quitting, and (d) quitStart Google Play store. Only one of the general apps (Stop-Tobacco) was developed by a university or government organization. However, no standardized method exists for identifying app creator. In the current study, the authors recorded the name of the “developer” as provided by the app store. However, future research could further assess the app developer by exploring the website of the app developer and other relevant information to examine whether the app developer is a public health organization, a private company, or other entity. This type of study would facilitate comparisons between apps based on developer.

Our finding that general apps have limited adherence content is consistent with previous studies; for instance, Abroms and colleagues reported that few apps (25 per cent) explicitly advised users to quit [23]. In the current study, 7.89 per cent of general apps and 12.5 per cent of adolescent apps advised users to quit. Similarly, a study of the presence of smoking cessation apps incorporating the 5A’s (ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange follow-up), which is recommended by U.S. National Clinical Practice Guidelines [33], reported that on average, apps addressed 2 of the 5A’s [25]. These findings are particularly relevant because research indicates that users rate apps with greater adherence content more positively [24], and apps with more of the 5A’s are downloaded more frequently [25]. Taken together, these findings suggest that smartphone app developers should consider exploring how adherence content can be incorporated into their apps.

Although this study has a number of strengths (e.g., focus on adherence content and adolescent-specific content), limitations should be noted. The search for general apps was limited to the first 20 apps in each store in order to create a comparison group of popular apps. A different search method could have yielded different results, but research suggests that smartphone app users rarely view results beyond the first or second page [32]. Additionally, there is no way to assess user engagement or use data from the public-facing Google Play store and Apple App store, which limits conclusions that can be drawn. This study assessed apps for their inclusion of the U.S. Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence; however, these guidelines were developed based on studies of face-to-face and phone-based interventions. It is not clear that these features are particularly relevant for app effectiveness—it is possible that some of these guidelines are less important for cessation apps or that there are features that are important in cessation apps that are not included in these guidelines.

Although some research has been done to understand the content and components of text-message–based cessation interventions for young adult and general audiences [35], to the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to assess adolescent-specific smoking cessation content in Google Play and Apple apps. This initial review suggests that there are few smartphone apps specifically designed to assist adolescents to quit smoking. However, on average, adolescent apps include more adherence content and adolescent-specific content than general apps. Although this review assesses the extent to which mobile apps that appear in the app store are grounded in the clinical practice guidelines, there is a dearth of published literature on the effectiveness of these apps in improving cessation outcomes. As the public health community continues to explore the potential of mobile health approaches for smoking cessation, future research should consider both the reach of adolescent-tailored apps and the impact of these apps on cessation outcomes.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Translational Behavioral Medicine online.

Funding:

The writing of this manuscript was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) K23 DA042130 (PI: Montgomery). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of NIDA or National Institutes of Health.

Author Contributions:

CDR designed and led the study with mentorship from YP and EA and input from LM and KC. ELS, EG, RAY and CDR coded the apps. CDR completed all analyses and drafted the paper with help from LM, KC, EG, ELS and RAY. All authors contributed to editing and finalizing the paper.

Acknowledgments

CDR is supported by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Prevention Fellowship Program. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The QuitSTART app was developed and is supported by the Smokefree.gov program at the National Cancer Institute.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants and animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent: This study does not involve human participants and informed consent was therefore not required.

References

- 1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2012. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General Available at http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/preventing-youth-tobacco-use/full-report.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. Pechacek T. Surgeon General’s Report—Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults. Presented at: Natioanl Conference on Tobacco or Health Kansas City, Missouri; 2012, August. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neff LJ, Arrazola RA, Caraballo RS, et al. Frequency of tobacco use among middle and high school students–United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(38):1061–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tworek C, Schauer GL, Wu CC, Malarcher AM, Jackson KJ, Hoffman AC. Youth tobacco cessation: quitting intentions and past-year quit attempts. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(2 Suppl 1):S15–S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). High school students who tried to quit smoking cigarettes – United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(16), 428–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Babb S, Malarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. Quitting smoking among adults – United States, 2000-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1457–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of cessation methods among smokers aged 16–24 years – United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(50), 1351–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stanton A, Grimshaw G. Tobacco cessation interventions for young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003289.pub5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Michaelidou N, Dibb S, Ali H. The effect of health, cosmetic and social antismoking information themes on adolescents’ beliefs about smoking. Int J Advert. 2008;27(2), 235–250. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith KH, Stutts MA. Effects of short-term cosmetic versus long-term health fear appeals in anti-smoking advertisements on the smoking behaviour of adolescents. J Consum Behav. 2003;3(2), 157–177. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weiss C, Hanebuth D, Coda P, Dratva J, Heintz M, Stutz EZ. Aging images as a motivational trigger for smoking cessation in young women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(9):3499–3512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Semer N, Ellison J, Mansell C, et al. Development and evaluation of a tobacco cessation motivational program for adolescents based on physical attractiveness and oral health. J Dent Hyg. 2005;79(4):9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kobus K. Peers and adolescent smoking. Addiction. 2003;98(Suppl 1):37–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee E, Tak Y. Peer and parental influences on adolescent smoking. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2005;35(4):694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sussman S, Dent CW, Severson H, Burton D, Flay BR. Self-initiated quitting among adolescent smokers. Prev Med. 1998;27(5 Pt 3):A19–A28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Byrne DG, Mazanov J. Sources of adolescent stress, smoking and the use of other drugs. Stress Med. 1999;15(4), 215–227. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Siqueira L, Diab M, Bodian C, Rolnitzky L. Adolescents becoming smokers: the roles of stress and coping methods. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27(6):399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gulliver A, Farrer L, Chan JK, et al. Technology-based interventions for tobacco and other drug use in university and college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2015;10:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lenhart A. Teens, social media & technology overview 2015. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rideout V, Fox S. n.d. Digital health practices, social media use, and mental well-being among teens and young adults in the U.S Available at https://www.hopelab.org/reports/pdf/a-national-survey-by-hopelab-and-well-being-trust-2018.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2016.

- 21. Frey RM, Xu R, Ilic A. Mobile app adoption in different life stages: an empirical analysis. Pervasive Mob Comput. 2017;40, 512–527. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mermelstein R. Teen smoking cessation. Tob Control. 2003;12(Suppl 1):i25–i34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abroms LC, Lee Westmaas J, Bontemps-Jones J, Ramani R, Mellerson J. A content analysis of popular smartphone apps for smoking cessation. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(6):732–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abroms LC, Padmanabhan N, Thaweethai L, Phillips T. iPhone apps for smoking cessation: a content analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(3):279–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoeppner BB, Hoeppner SS, Seaboyer L, et al. How smart are smartphone apps for smoking cessation? a content analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):1025–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ubhi HK, Kotz D, Michie S, et al. Comparative analysis of smoking cessation smartphone applications available in 2012 versus 2014. Addict Behav. 2016;58:175–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ubhi HK, Michie S, Kotz D, van Schayck OC, Selladurai A, West R. Characterising smoking cessation smartphone applications in terms of behaviour change techniques, engagement and ease-of-use features. Transl Behav Med. 2016;6(3):410–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haskins BL, Lesperance D, Gibbons P, Boudreaux ED. A systematic review of smartphone applications for smoking cessation. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(2):292–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fanshawe TR, Halliwell W, Lindson N, Aveyard P, Livingstone-Banks J, Hartmann-Boyce J. Tobacco cessation interventions for young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003289.pub6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brown K, Campbell SW, Ling R. Mobile phones bridging the digital divide for teens in the US?Future Internet. 2011;3(2), 144–158. doi: 10.3390/fi3020144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee G, Raghu TS. Determinants of mobile apps’ success: evidence from the app store market. J Manage Inf Syst. 2014;31(2), 133–170. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ramo DE, Popova L, Grana R, Zhao S, Chavez K. Cannabis mobile apps: a content analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(3):e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker T, and the Guideline Panel, Liaisons, and Staff Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wartella E, Rideout V, Zupancic H, Beaudoin-Ryan L, Lauricella A.. Teens, health, and technology: a national survey. Evanston, IL: Center on Media and Human Development School of Communication: Northwestern University; 2015. Available at http://cmhd.northwestern.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/1886_1_SOC_ConfReport_TeensHealthTech_051115.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kong G, Ells DM, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Text messaging-based smoking cessation intervention: a narrative review. Addict Behav. 2014;39(5):907–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.