Abstract

Background

The high occurrence and acute and chronic sequelae of traumatic brain injury (TBI) cause major healthcare and socioeconomic challenges. This study aimed to describe outcome, in-hospital healthcare consumption and in-hospital costs of patients with TBI.

Methods

We used data from hospitalised TBI patients that were included in the prospective observational CENTER-TBI study in three Dutch Level I Trauma Centres from 2015 to 2017. Clinical data was completed with data on in-hospital healthcare consumption and costs. TBI severity was classified using the Glasgow Coma Score (GCS). Patient outcome was measured by in-hospital mortality and Glasgow Outcome Score–Extended (GOSE) at 6 months. In-hospital costs were calculated following the Dutch guidelines for cost calculation.

Results

A total of 486 TBI patients were included. Mean age was 56.1 ± 22.4 years and mean GCS was 12.7 ± 3.8. Six-month mortality (4.2%–66.7%), unfavourable outcome (GOSE ≤ 4) (14.6%–80.4%) and full recovery (GOSE = 8) (32.5%–5.9%) rates varied from patients with mild TBI (GCS13–15) to very severe TBI (GCS3–5). Length of stay (8 ± 13 days) and in-hospital costs (€11,920) were substantial and increased with higher TBI severity, presence of intracranial abnormalities, extracranial injury and surgical intervention. Costs were primarily driven by admission (66%) and surgery (13%).

Conclusion

In-hospital mortality and unfavourable outcome rates were rather high, but many patients also achieved full recovery. Hospitalised TBI patients show substantial in-hospital healthcare consumption and costs, even in patients with mild TBI. Because these costs are likely to be an underestimation of the actual total costs, more research is required to investigate the actual costs-effectiveness of TBI care.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00701-020-04384-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, In-hospital costs, Mortality, Functional outcome

Introduction

Recent estimates indicate that worldwide up to 69 million people a year sustain a traumatic brain injury (TBI). [15] The high incidence of TBI and the associated acute and chronic sequelae cause substantial healthcare and socio-economic challenges. [32] Available treatments are unfortunately still largely unproven or unsatisfactory. [9, 15, 32, 75] Patients suffer from the medical consequences of TBI, which range from headache and fatigue to severe disabilities and even death [4, 14, 18, 59, 68]. The total global accompanying costs of around US$ 400 billion a year are a major challenge from a socioeconomic perspective [32], especially considering the fact that TBI-related healthcare costs are rising, while healthcare budgets remain limited [19]. The in-hospital costs related to TBI represent a substantial part of the total utilised resources [49]. Unfortunately, understanding and generalising the in-hospital costs of individual TBI patients from available literature remains difficult because methodological heterogeneity of TBI cost studies is high and study quality often inadequate [1, 30, 69].

Accurate insight in TBI-related costs is essential to substantiate research initiatives that aim to improve treatment efficiency. It also guides policymakers on the rational allocation of resources without compromise of patient outcome. To allow healthcare professionals to continue to provide optimal care for their patients, high-quality cost-analysis studies are urgently needed [1, 30].

Therefore, the aim of this study is to describe outcome, in-hospital healthcare consumption and in-hospital costs of hospitalised TBI patients.

Materials and methods

This study followed the recommendations from the ‘Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology’ STROBE statement [76].

Study design and patients

Patients were included in three level 1 trauma hospitals from January 2015 to September 2017. All hospitals are located in an urban area in the mid-Western part of the Netherlands and participated in the Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) project. The CENTER-TBI Core study (clinicaltrials.gov NCT02210221; RRID: SCR_015582) is a prospective multicentre longitudinal observational study conducted in 65 centres across Europe and Israel [31]. The project aimed to improve TBI characterisation and classification and to identify best clinical care. The responsible institutional review board (METC Leiden) approved this study (P14.222).

Patients were included in the CENTER-TBI Core study using the following criteria: (1) clinical diagnosis of TBI, (2) clinical indication for head CT scan, (3) presentation to study centre within 24 h after injury and (4) informed consent following Dutch requirements, including patient, proxy and deferred consent. Patients were excluded when they had a severe pre-existing neurological disorder that would confound outcome assessments or in case of insufficient understanding of the Dutch or English language.

Clinical data

Clinical data were prospectively collected by using a web-based electronic case report form (CRF) (QuesGen System Incorporated, Burlingame, CA, USA). Data were obtained from electronic patient files and patient interviews and when necessary initially recorded on a hardcopy CRF. Data collection was completed by a local research staff that was specifically trained for this project. The site’s principal investigator supervised the project. Data were de-identified by using a randomly generated GUPI (Global Unique Patient Identifier) and was stored on a secure database, hosted by the International Neuroinformatics Coordinating Facility (INCF; www.incf.org) in Stockholm, Sweden.

Data was extracted in December 2019 (version 2.1) using a custom-made data access tool Neurobot (http://neurobot.incf.org), developed by INCF (RRID: SCR_01700). Extracted data included baseline demographic, trauma and injury information, results of neurological assessments, imaging (first head CT scan) and patient outcome. This database was merged with separately collected data on in-hospital healthcare consumption and in-hospital costs, which is explained later. Discrepancies were resolved by source data verification.

Baseline Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) Total Score, GCS Motor Score and pupillary reactivity variables were collected. TBI severity was then classified by using the GCS (GCS13–15; mild TBI, GCS9–12; moderate TBI, GCS3–8; severe TBI, GCS3–5; very severe TBI) [64]. These values were derived variables that were centrally calculated using the IMPACT methodology, taking a post stabilisation value and if absent work back in time towards prehospital values. Out of 19 missing GCS values, 8 were completed by using emergency department arrival GCS score. Intubation was calculated as a GCS verbal score of 1. Major extracranial injury was defined by AIS body region ≥ 3. Characteristics from the first head CT scan were assessed by a central review panel [73]. Six out of seven missing central assessments were completed by using the assessments of local radiologists. Outcome data included in-hospital mortality and 6-month Glasgow Outcome Score–Extended (GOSE). GOSE outcome was dichotomised in favourable (GOSE ≥ 5) and unfavourable (GOSE ≤ 4) [78].

In-hospital healthcare consumption

We collected in-hospital healthcare consumption data from electronic patient records by using a predefined cost assessment database. The Dutch National Health Care Institute Guidelines for healthcare cost calculation were followed [23]. Units (e.g. number of admission days, number of diagnostics) were collected independently by two researchers from the electronic patient files. There were five main categories: (1) admission; including length of stay (LOS) in (non-)ICU with consultations, (2) surgical interventions, (3) imaging, (4) laboratory; including blood products and (5) other; including ambulance transportation and outpatient visits [70]. Non-ICU admission was defined as admission to a ward or medium care. In-hospital healthcare consumption and costs were calculated for all included patients (Supplement 1).

In-hospital costs

We focused on the in-hospital costs from a healthcare perspective. Costs of re-admissions and costs of visits to the Outpatient Clinic related to the trauma were also included. The methods and reference prices as described in the Dutch Guidelines for economic healthcare evaluations were used to calculate in-hospital costs [23]. Costs were calculated by multiplying the number of consumed units with the corresponding guideline reference price. Guideline reference prices are based on non-site specific large patient cohorts which improves their generalisability and interpretation [23]. When reference prices were not mentioned, the remaining units were valued by using amounts per unit as reported by The Netherlands Healthcare Authority (NZa) (i.e. diagnostics) [83] or by using their average national price, based on declared fees (i.e. surgical interventions, consultations) [82]. All costs were converted to the last year of patient inclusion (2017) using the national general consumer price index (CBS) and rounded to the nearest ten euros. One EURO equalled $1.05 dollar on the 1st of January 2017 (Supplement 1).

Statistical methods

Data were analysed using descriptive statistics. Baseline data were presented as absolute numbers and percentages. Continuous variables, like LOS and costs, were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range 25–75). Subgroups were made using age, TBI severity, pupillary abnormalities, intracranial abnormalities, surgical intervention and outcome. ANOVA and χ2 were used for comparison of continuous and categorical variables across different subgroups. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM’s statistical package for social sciences version 25.0 (SPSS). Figures were designed using GraphPad Prism 8.

Results

A total of 486 patients with TBI were included in this study. Patients had a mean age of 56.1 ± 22.4 years and were predominantly male (60.5%) (Table 1). Nearly all patients sustained a closed head injury (98.4%). TBI was mainly caused by incidental falls (54.3%) or road traffic accidents (36.2%) and occurred on streets (56.2%) or at home (31.5%). The mean baseline GCS was 12.7 ± 3.8 and mean injury severity score (ISS) was 20 ± 16. Patients sustained mild TBI (N = 354, 72.8%), moderate TBI (N = 43, 8.8%) and severe TBI (N = 78, 16.1%), of which 51 were very severe (10.5%). Loss to follow-up was 14.2% and not significantly different between severity groups.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and outcome

| All (N = 486) | Mild TBI (N = 354) | Moderate TBI (N = 43) | Severe TBI (N = 78) | Very severe TBI (N = 51) | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 294 (60.5) | 211 (59.6) | 25 (58.1) | 54 (69.2) | 36 (70.6) | 0.265 |

| Age (years) | 56.1 ± 22.4 | 56.6 ± 22.2 | 58.5 ± 22.4 | 52.2 ± 22.6 | 50.9 ± 23.3 | 0.222 |

| ≤ 18 | 25 (5.1) | 21 (5.9) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (2.6) | 2 (3.9) | 0.467 |

| 19–64 | 255 (52.5) | 184 (52.0) | 21 (48.8) | 46 (59.0) | 30 (58.8) | |

| ≥ 65 | 206 (42.4) | 149 (42.1) | 21 (48.8) | 30 (38.5) | 19 (37.3) | |

| Stratum | < 0.001 | |||||

| Admission | 319 (65.6) | 288 (81.4) | 16 (37.2) | 9 (11.5) | 5 (9.8) | |

| ICU | 167 (34.4) | 66 (18.6) | 27 (62.8) | 69 (88.5) | 46 (90.2) | |

| Location of injury | 0.137 | |||||

| Street/highway | 273 (56.2) | 201 (56.8) | 22 (51.2) | 45 (57.7) | 31 (60.8) | |

| Home/domestic | 153 (31.5) | 113 (31.9) | 11 (25.6) | 25 (32.1) | 15 (29.4) | |

| Work/school | 14 (2.9) | 8 (2.3) | 5 (11.6) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.0) | |

| Sport/recreational | 18 (3.7) | 14 (4.0) | 2 (4.7) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Public location | 25 (5.1) | 15 (4.2) | 3 (7.0) | 6 (7.7) | 4 (7.8) | |

| Other/unknown | 2 (0.6) | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Cause of injury | 0.136 | |||||

| Road traffic accident | 176 (36.2) | 125 (35.3) | 14 (32.6) | 35 (44.9) | 25 (49.0) | |

| Incidental fall | 264 (54.3) | 200 (56.5) | 21 (48.8) | 35 (44.9) | 20 (39.2) | |

| Non-intentional injury | 12 (2.5) | 8 (2.3) | 2 (4.7) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.0) | |

| Violence/assault | 10 (2.1) | 8 (2.3) | 2 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Suicide attempt | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (2.6%) | 2 (3.9) | |

| Other/unknown | 21 (4.3) | 13 (3.6) | 3 (7.0) | 5 (6.4) | 3 (5.9) | |

| Glasgow Coma Score | 12.7 ± 3.8 | 14.7 ± 0.6 | 10.6 ± 0.9 | 4.7 ± 1.9 | 3.5 ± 0.7 | N/A |

| GCS Motor score | 5.3 ± 1.6 | 6.0 ± 0.4 | 5.0 ± 1.3 | 2.3 ± 1.7 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | |

| GCS 13–15 | 354 (72.8) | 354 (100) | – | – | – | |

| GCS 9–12 | 43 (8.8) | – | 43 (100) | – | – | |

| GCS 3–8 | 78 (16.1) | – | – | 78 (100) | – | |

| GCS 3–5 | 51 (10.5) | – | – | 51 (65.4) | 51 (100) | |

| Missing | 11 (2.3) | – | – | – | – | |

| Pupillary abnormalities | < 0.001 | |||||

| Both reacting | 423 (87.0) | 343 (98.0) | 39 (90.7) | 38 (48.7) | 19 (37.3) | |

| One reacting | 14 (2.9) | 5 (1.4) | 2 (4.7) | 7 (9.0) | 4 (7.8) | |

| Both non-reacting | 37 (7.6) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (4.7) | 33 (42.3) | 28 (54.9) | |

| Missing | 12 (2.5) | 4 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Findings first CT scan | ||||||

| Intracranial abnormalities | 263 (54.1) | 160 (45.2) | 30 (69.8) | 68 (87.2) | 43 (84.3) | < 0.001 |

| Contusion | 130 (26.7) | 68 (19.2) | 22 (51.2) | 38 (48.7) | 26 (51.0) | < 0.001 |

| Traumatic SAH | 185 (38.1) | 101 (28.5) | 26 (60.5) | 56 (71.8) | 37 (72.5) | < 0.001 |

| Epidural hematoma(s) | 47 (9.7) | 27 (7.6) | 7 (16.3) | 13 (16.7) | 9 (17.6) | < 0.001 |

| Subdural hematoma(s) | 136 (28.0) | 68 (19.2) | 22 (51.2) | 43 (55.1) | 28 (54.9) | < 0.001 |

| Skull fracture(s) | 180 (37.0) | 97 (27.4) | 25 (58.1) | 55 (70.5) | 39 (76.5) | < 0.001 |

| Compressed basal cisterna | 88 (18.1) | 30 (8.5) | 9 (20.9) | 47 (60.3) | 34 (66.7) | < 0.001 |

| Midline shift > 5 mm | 65 (13.4) | 21 (5.9) | 10 (23.3) | 31 (39.7) | 20 (39.2) | < 0.001 |

| Mass lesion > 25 cc | 80 (16.5) | 26 (7.3) | 14 (32.6) | 37 (47.4) | 26 (51.0) | < 0.001 |

| Uninterpretable** | 10 (2.1) | 5 (1.4) | 4 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Injury severity | ||||||

| Brain Injury AIS | 3.1 ± 1.2 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 1,2 | 4.6 ± 1.2 | 4.8 ± 1.2 | < 0.001 |

| ISS | 20 ± 16 | 15 ± 9 | 22 ± 16 | 39 ± 22 | 43 ± 21 | < 0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality | 60 (12.3) | 8 (2.3) | 8 (18.6) | 42 (53.8) | 32 (62.7) | < 0.001 |

| GOSE at 6 months | 5.72 ± 2.55 | 6.5 ± 1.8 | 4.6 ± 2.7 | 2.9 ± 2.7 | 2.4 ± 2.5 | |

| Favourable/unfavourable*** | 72.9%/27.1% | 85.4%/14.6% | 55.3%/44.7% | 29.0%/71.0% | 19.6%/80.4% | < 0.001 |

| 1 | 73 (15.0) | 15 (4.2) | 10 (23.3) | 45 (57.7) | 34 (66.7) | < 0.001 |

| 2/3 | 17 (3.5) | 10 (2.8) | 6 (14.0) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 4 | 23 (4.7) | 19 (5.4) | 1 (2.3) | 3 (3.8) | 3 (5.9) | |

| 5 | 25 (5.1) | 18 (5.1) | 5 (11.6) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (2.0) | |

| 6 | 38 (7.8) | 31 (8.8) | 4 (9.3) | 3 (3.8) | 1 (2.0) | |

| 7 | 110 (22.6) | 93 (26.3) | 4 (9.3) | 10 (12.8) | 4 (7.8) | |

| 8 | 131 (27.0) | 115 (32.5) | 8 (18.6) | 5 (6.4) | 3 (5.9) | |

| Loss to follow-up | 69 (14.2) | 53 (15.0) | 5 (11.6) | 9 (11.5) | 5 (9.8) | 0.650 |

Values are reported as: Number (percentage). Mean ± SD. AIS, abbreviated injury scale; CT scan, computed tomography scan; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score; GOSE, Glasgow Outcome Score–Extended; ICU, intensive care unit; SAH, subarachnoid haemorrhage

*p values were derived from ANOVA for continuous characteristics and χ2 statistics for categorical characteristics, comparing TBI severity categories (severe TBI, moderate TBI, mild TBI). The p value assessed compatibility with the null hypothesis of no differences between TBI severity categories

**Numbers from TBI severity subgroups do not always match the numbers that are reported for all patients because baseline GCS data was missing for 11 patients. Also, data from 1 CT scan could not be retrieved

***Calculated excluding missing. Favourable and unfavourable were defined as GOSE 5–8 and GOSE 1–4 respectively

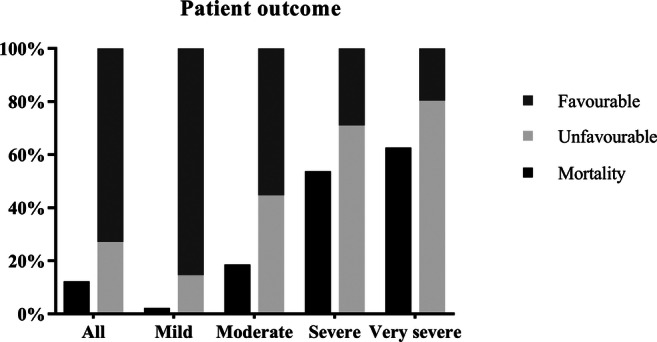

Patient outcome

Mean in-hospital mortality was 12.3% and ranged from 2.3% for patients with mild TBI to 62.7% for patients with very severe TBI (Table 1). The 6-month GOSE follow-up was available for 417 patients (85.8%). Favourable outcome (GOSE ≥ 5) was achieved by 85.4% of patients with mild, 55.3% with moderate, 29.0% with severe and 19.6% with very severe TBI (Fig. 1). A GOSE of 2–4 was found in 40 survivors (8.2%), of which 17 (3.5%) were in a vegetative state (GOSE = 2) or required full assistance in daily life (GOSE = 3). Nearly a third of patients reported full recovery (GOSE = 8) after mild (32.5%), 18.6% after moderate, 6.4% after severe and 5.9% after very severe TBI.

Fig. 1.

In-hospital mortality and functional outcome (favourable GOSE 5–8, unfavourable GOSE 1–4) at 6 month follow-up for patients with TBI in different severities

Length of stay and surgical interventions

Mean total LOS was 8 days (2 days on ICU and 6 days non-ICU). LOS significantly increased with TBI severity, presence of major extracranial injury, surgical intervention(s) and presence of all types of intracranial abnormalities except epidural hematoma (Table 2, Fig. 2). Patients that required ICP monitoring and/or a decompressive craniectomy showed longest mean LOS (27 and 28 days respectively). LOS was short in patients without intracranial abnormalities (5 days). Patients with two non-reacting pupils also showed a significantly shorter LOS (5 days) compared with those with either one (17 days) or two reacting pupils (8 days).

Table 2.

Length of stay and in-hospital costs

| Patient category | N | Total LOS | ICU LOS | Non-ICU LOS | Total costs | Admission costs | Surgery costs | Radiology costs | Laboratory costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 486 | 8 ± 13 | 2 ± 5 | 6 ± 10 | 11,920; 5200 (2780-12,500) | 7900; 2670 (1430-7090) | 1490; 0 (0–1820) | 840; 670 (350–1080) | 650; 130 (59–580) |

| Age | * | ||||||||

| ≤ 18 | 25 | 3 ± 4 | 1 ± 4 | 2 ± 2 | 6100; 2550 (1830–6470) | 4110; 1840 (1180-2600) | 650; 0 (0–0) | 460; 300 (130–440) | 210; 50 (0–70) |

| 19–64 | 255 | 8 ± 15 | 2 ± 5 | 6 ± 11 | 12,640; 4560 (2720-12,630) | 8230; 2440 (1370-6810) | 1760; 0 (0–3160) | 900; 780 (370–1160) | 620; 100 (60–470) |

| ≥ 65 | 206 | 8 ± 11 | 2 ± 5 | 7 ± 8 | 11,720; 6240 (3070-13,060) | 7940; 3800 (1840-7620) | 1270; 0 (0–0) | 810; 650 (350–980) | 740; 200 (70–780) |

| TBI severity | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| GCS 13–15 | 354 | 6 ± 8 | 1 ± 3 | 5 ± 6 | 7800; 3880 (2550-8630) | 4900; 2050 (1430-5250) | 1000; 0 (0–0) | 720; 570 (310–930) | 330; 80 (60–240) |

| GCS 9–12 | 43 | 14 ± 15 | 4 ± 6 | 10 ± 12 | 20,210; 12,480 (5370-27,220) | 13,900; 8680 (2500-18,910) | 3010; 0 (0–4520) | 1140; 890 (480–1560) | 1170; 570 (160–1820) |

| GCS 3–8 | 78 | 15 ± 22 | 6 ± 9 | 9 ± 18 | 26,600; 12,340 (7730-41,260) | 18,630; 6570 (2670-26,410) | 2950; 0 (0–4520) | 1240; 980 (720–1650) | 1660; 730 (240–2550) |

| GCS 3–5 | 51 | 14 ± 20 | 6 ± 8 | 7 ± 17 | 26,350; 12,500 (7730-42,430) | 18,140; 6230 (2670-30,600) | 2790; 0 (0–4530) | 1310; 1010 (760–1940) | 1730; 790 (240–2980) |

| Pupil reactivity | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| Both reacting | 423 | 8 ± 13 | 2 ± 5 | 6 ± 10 | 11,270; 4650 (2700-12,290) | 7540; 2600 (1430-7070) | 1400; 0 (0–0) | 830; 650 (340–1070) | 560; 110 (60–480) |

| One reacting | 14 | 17 ± 16 | 8 ± 11 | 9 ± 7 | 31,940; 13,600 (5070-51,490) | 22,330; 6420 (2890-33,050) | 4210; 3840 (0–7440) | 1250; 1290 (290–2260) | 2330; 1120 (370–4480) |

| None reacting | 37 | 5 ± 6 | 3 ± 5 | 2 ± 5 | 13,210; 8210 (6220-14,060) | 7570; 2670 (2340-7210) | 1800; 0 (0–4520) | 880; 840 (660–1010) | 1160; 570 (210–1230) |

| Early CT scan | |||||||||

| Yes abnormalities | 263 | 10 ± 15* | 3 ± 6* | 7 ± 11* | 15,780; 8240 (3690-15,750)* | 10,830; 4340 (1880-10,290)* | 1860; 0 (0–3720)* | 930; 760 (400–1190)* | 940; 240 (70–1080)* |

| No abnormalities | 212 | 5 ± 8 | 0 ± 2 | 4 ± 7 | 6490; 3180 (2350-6670) | 3860; 1840 (1180-3950) | 870; 0 (0–0) | 700; 500 (290–920) | 260; 70 (60–190) |

| Contusion | 139 | 12 ± 16* | 3 ± 6* | 8 ± 13* | 18,060; 9810 (4100-21,560)* | 12,740; 5580 (2340-15,670)* | 2190; 0 (0–3720)* | 970; 800 (500–1210)* | 1010; 370 (70–1230)* |

| Traumatic SAH | 185 | 11 ± 17* | 3 ± 7* | 8 ± 13* | 17,730; 9090 (4130-20,640)* | 12,250; 4930 (2340-13,520)* | 2120; 0 (0–4520)* | 990; 840 (450–1280)* | 1080; 400 (80–1280)* |

| Epidural hematoma(s) | 47 | 10 ± 15 | 3 ± 6 | 8 ± 11 | 16,320; 8240 (3170-14,060) | 11,390; 4670 (1840-11,520) | 1980; 0 (0–1820) | 910; 790 (400–1140) | 720; 220 (60–710) |

| Subdural hematoma(s) | 136 | 11 ± 16* | 3 ± 6* | 8 ± 12* | 16,670; 8800 (4210-20,290)* | 11,180; 4680 (1880-13,170)* | 2290; 0 (0–4520) | 950; 790 (460–1200)* | 1100; 410 (100–1350)* |

| Skull fracture(s) | 180 | 9 ± 15* | 3 ± 6* | 7 ± 11 | 15,450; 8190 (3350-16,560)* | 10,620; 4140 (1970-12,300)* | 1730; 0 (0–3160) | 900; 770 (400–1190) | 900; 240 (60–1070)* |

| Compressed basal cisterna | 88 | 12 ± 18* | 4 ± 7* | 8 ± 13 | 21,000; 10,520 (6500-26,030)* | 13,890; 5710 (2670-17,210)* | 3190; 1580 (0–4520)* | 1080; 860 (590–1520)* | 1460; 570 (200–1930)* |

| Midline shift > 5 mm | 65 | 12 ± 15* | 4 ± 7* | 8 ± 12 | 21,290; 12,410 (6810-26,440)* | 13,950; 6530 (2670-16,940)* | 3630; 4520 (0–4530)* | 1050; 820 (570–1480)* | 1420; 770 (240–1910)* |

| Mass lesion > 25 cc | 80 | 12 ± 18* | 5 ± 8* | 8 ± 13 | 21,590; 11,840 (6960-25,230)* | 14,620; 6630 (2670-15,060)* | 3230; 3530 (0–4520)* | 1120; 840 (590–1540)* | 1420; 560 (220–1520)* |

| Surgical intervention | |||||||||

| Intracranial surgery | 67 | 21 ± 23* | 8 ± 9* | 13 ± 18* | 36.870; 26,440 (13,210-48,500)* | 24,970; 15,560 (6740-33,050)* | 6670; 4530 (4520-8250)* | 1510; 1230 (840–2100)* | 2300; 1480 (570–4280)* |

| No intracranial surgery | 419 | 6 ± 8 | 1 ± 4 | 5 ± 7 | 7930; 4110 (2600-8960) | 5170; 2400 (1430-5300) | 670; 0 (0–0) | 730; 600 (310–960) | 390; 90 (60–300) |

| ICP monitoring | 40 | 27 ± 28* | 12 ± 9* | 16 ± 22* | 47,260; 41,850 (21,480-63,500)* | 33,670; 26,530 (13,100-50,180)* | 7220; 5430 (4520-8250)* | 1690; 1710 (870–2310)* | 2880; 1960 (1040-4780)* |

| No ICP monitoring | 446 | 6 ± 9 | 1 ± 4 | 5 ± 7 | 8750; 4510 (2640-10,900) | 5590; 2500 (1430-5840) | 980; 0 (0–0) | 760; 630 (310–980) | 450; 110 (60–400) |

| Craniotomy | 33 | 19 ± 21* | 7 ± 9* | 12 ± 16* | 33,200; 21,410 (12,210-42,430)* | 21,790; 11,900 (5690-26,650)* | 7200; 4530 (4520-9060)* | 1300; 970 (610–1750)* | 1890; 1080 (500–2750)* |

| Decompressive craniectomy | 24 | 28 ± 27* | 11 ± 9* | 17 ± 21* | 49,750; 41,970 (26,400-68,830)* | 34,370; 26,530 (14,120-50,400)* | 8880; 8240 (4530-10,500)* | 1840; 1880 (1110-2310)* | 3230; 2850 (1290-4940)* |

| Extracranial surgery | 65 | 12 ± 14* | 2 ± 6 | 10 ± 12* | 19,960; 13,900 (10,740-24,630)* | 11,620; 6190 (3350-13,510) | 5010; 3350 (3160-6490)* | 1250; 1190 (750–1680)* | 820; 310 (130–1070) |

| No extracranial surgery | 421 | 7 ± 13 | 2 ± 5 | 6 ± 9 | 10,680; 4130 (2610-10,050) | 7320; 2500 (1430-6400) | 950; 0 (0–0) | 770; 610 (310–970) | 630; 110 (60–530) |

| In hospital mortality | * | * | * | * | |||||

| Yes | 60 | 7 ± 9 | 4 ± 6 | 3 ± 6 | 17,250; 9020 (6540-22,550) | 10,790; 4330 (2670-14,540) | 2320; 0 (0–4520) | 980; 840 (640–1160) | 1490; 910 (240–1940) |

| No | 8 ± 13 | 2 ± 5 | 7 ± 10 | 11,170; 4530 (2640-11,890) | 7490; 2500 (1430-6740) | 1380; 0 (0–0) | 820; 640 (310–1070) | 530; 100 (60–420) | |

| GOSE 6 months | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| 1 | 73 | 9 ± 13 | 4 ± 7 | 4 ± 10 | 18,240; 8960 (5860-21,560) | 11,890: 4520 (2670-13,520) | 2370; 0 (0–4520) | 980; 820 (570–1200) | 1510; 970 (240–1960) |

| 2/3 | 17 | 30 ± 29 | 7 ± 9 | 23 ± 21 | 36,190; 17,260 (12,290–48,500) | 26,570; 13,010 (5420-34,890) | 4710; 3720 (0–7070) | 1850; 1750 (1320-2260) | 2060; 1460 (220–4280) |

| 4 | 23 | 8 ± 8 | 2 ± 6 | 6 ± 6 | 13,160; 7940 (2890-15,700) | 8420; 2890 (1620-8270) | 1760; 0 (0–3250) | 1180; 1040 (270–1800) | 670; 120 (60–460) |

| 5 | 25 | 9 ± 8 | 2 ± 3 | 7 ± 6 | 13,080; 10,150 (3840-15,130) | 8180; 5140 (2220-11,600) | 1930: 0 (0–1820) | 900; 830 (520–1140) | 730; 180 (70–920) |

| 6 | 38 | 7 ± 8 | 1 ± 2 | 7 ± 7 | 10,480; 5350 (3330-13,220) | 6210; 2790 (1370-6430) | 1810; 0 (0–3160) | 1000; 880 (530–1190) | 370; 80 (60–370) |

| 7 | 110 | 7 ± 9 | 1 ± 5 | 5 ± 7 | 9100; 4010 (2780-9550) | 6130; 2030 (1430-5840) | 840; 0 (0–0) | 770; 650 (370–980) | 410; 80 (60–360) |

| 8 | 131 | 4 ± 4 | 0 ± 1 | 4 ± 4 | 5780; 3210 (2310-7260) | 3560; 1880 (1180-4570) | 670; 0 (0–0) | 560; 410 (270–780) | 220; 70 (60–200) |

Values are reported as: mean ± SD or mean; median (IQR 25–75)

Favourable and unfavourable were defined as GOSE 5–8 and GOSE 1–4 respectively. AIS, abbreviated injury scale; CT scan, computed tomography scan; GCS, Glasgow Coma Score; GOSE, Glasgow Outcome Score–Extended; ICU, intensive care unit; SAH, subarachnoid haemorrhage

*p value < 0.05: p values were derived from ANOVA for continuous characteristics. The p value assessed compatibility with the null hypothesis of no differences in mean values between row categories. Costs were rounded to the nearest ten euros

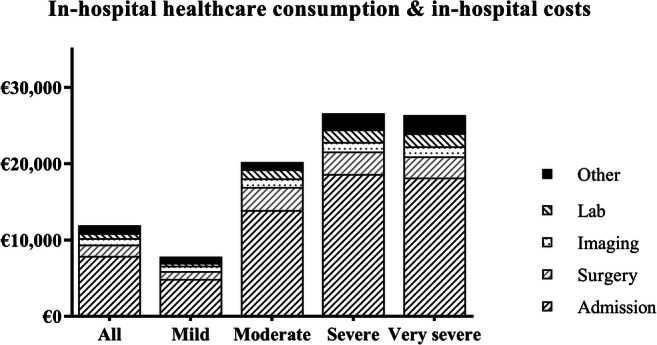

Fig. 2.

The mean in-hospital costs for patients with TBI, specified per severity category and per cost category to show their contribution to the total in-hospital costs

A total of 126 patients (27.2%) received a surgical intervention, of which 67 intracranial (13.8%) and 65 extracranial (13.4%). Intracranial surgery was significantly more common in more severely injured TBI subgroups (6.2% for mild, 34.9% for moderate and 35.9% for severe TBI) (Table 2).

In-hospital costs

Mean in-hospital costs were €11,918. €7896 was related to admission (66%), €1493 to surgery (13%) and €1042 to other (9%) (Table 2). Costs related to radiology (7%) and laboratory (5%) were smaller contributors. Average in-hospital costs were €7795 for mild, €20,207 for moderate €26,595 for severe and €26,349 for very severe TBI patients (Fig. 2). Presence of intracranial abnormalities on the first CT scan nearly doubled total in-hospital costs (€15,783 vs. €8238). Intracranial surgery or ICP monitoring quadrupled the costs (respectively €36,866 vs. €7928 and €47,255 vs. €8748). Patients with a decompressive craniectomy (€49,754), ‘regular’ craniotomy (€33,195) or extracranial surgery (€19,957) were also more expensive compared with non-surgically treated patients. Patients with a 6-month GOSE score of 8 showed the lowest in-hospital costs of € 5774, while patients with a GOSE score of 2/3 showed costs of €36,190.

Discussion

The current study found substantial in-hospital healthcare consumption and high in-hospital costs for hospitalised TBI patients, even after mild TBI. Both length of stay and in-hospital costs increased with TBI severity and presence of intracranial abnormalities and extracranial injuries. The most important cost drivers were admission and surgical intervention. Patients from all TBI severity categories were able to achieve full recovery, even after sustaining very severe TBI. Nonetheless, mortality and unfavourable outcome rates were high and the majority of patients reported remaining deficits or disabilities after 6 months.

Study cohort

The predominance of male gender, injury mechanisms (road traffic accidents and falls) and distribution of TBI severity were in accordance with recent literature [7, 15, 29, 33]. The mean age of 56 years was rather high compared to earlier research [7], but matched changing epidemiological patterns [32]. The number of intracranial CT abnormalities in mild TBI patients was higher compared with that in literature (45.2% vs. 16.1%) [26]. This is likely caused by different inclusion criteria (hospital admission after TBI vs. ED presentation with head CT after suspected TBI) and differences in accuracy between central and local radiological reading [73]. The number of patients with major extracranial injury (AIS ≥ 3) and pupillary abnormalities was also higher compared with that in literature [72, 77] and the overall CENTER-TBI Core study cohort [59]. These factors, with other factors like comorbidities and use of anticoagulants, could have negatively influenced patient outcome and/or increased the reported in-hospital healthcare consumption and in-hospital costs in this study.

Patient outcome

Mortality rates were generally high, but difficult to compare with other studies due to methodological differences [16, 32, 51]. One meta-analysis reported higher ‘all time point’ mortality rates for patients of all TBI severities [38], while other studies showed lower mortality rates for mild TBI [10], moderate TBI [16] and severe TBI [51, 58]. Favourable outcome (6-month GOSE) rates were generally higher in literature [39, 51, 16]. Differences in patient outcome can largely be explained by patient related factors that are known to be associated with worse outcome. Such factors include higher age, higher injury severity, poorer initial neurologic condition and higher TBI severity (defined by GCS) and are reported above average in our cohort [28, 38, 71]. For instance, the inclusion of patients with a GCS = 3 and/or bilateral pupillary abnormalities influences the comparison of patient outcome, as they are typically excluded in literature because of their often-perceived dismal prognosis [65]. Even the most severely injured patients that were able to achieve favourable outcome and even full recovery, although rarely, has been reported previously [71].

The increase in mortality rates (12.3 to 15%) and data on persisting deficits and disabilities after 6 months confirm the need for increased vigilance and attention for rehabilitation or long-term care opportunities. Sustained health problems after TBI have also been reported by long-term follow up studies [21, 42, 52, 74], some reporting deterioration between 5 and 10 years [17], others reporting remaining functional limitations up to 20 years after moderate and severe TBI [3]. Long-term impairments are not limited to severe TBI, but are also reported after mild TBI [14, 68]. Despite the short 6-month follow-up, our results support statements that consider TBI to be an acute injury resulting into a chronic health condition that requires continued care for most patients. TBI should therefore be addressed as such by healthcare providers, researchers and policymakers [60, 79].

Length of stay

Healthcare consumption in terms of length of stay and surgical intervention was substantial. However, when comparing our overall results to numbers for patients (age < 65) from Canada, our mean LOS (days) was shorter for all patients (8 vs. 13), for patients with mild TBI (6 vs. 9) and severe TBI (15 vs. 22) but similar for moderate TBI (14 vs. 14) [62]. Median LOS was also shorter for mild TBI (3 vs. 9), moderate TBI (7 vs. 11) and severe TBI (7 vs. 12) compared with recent numbers from England and Wales [29]. In a review on hospital costs for severe TBI patients, total LOS ranged between 10 and 36.8 days and ICU LOS between 7.9 and 25.8 days [69]. The large ranges are exemplary for the existing variation, that is, primarily caused by patient case-mix and treatment-related factors [40]. Several factors that we found to be associated with an increased total LOS were also mentioned in literature: lower GCS, higher TBI severity and the presence of extracranial injury [13, 62], ICP monitoring [46, 61] and decompressive craniectomy [27, 53].

There were several exceptions. For instance, the most severely injured TBI patients were sometimes admitted to the ward because of treatment limiting decisions shortly after presentation [50]. This could explain the lower LOS and lower in-hospital costs for very severe TBI patients and patients with two non-reacting pupils. Similarly, some mild TBI patients could have been admitted to the ICU because of (suspected) deterioration or over-triage or non-TBI related issues such as age, comorbidities, and concomitant extracranial injuries [6, 36].

In-hospital costs

The median costs and interquartile range indicate that costs were skewed by a small group of patients with very high costs. The reported costs were generally similar to available literature. One Dutch study reported that the direct and indirect costs for all TBI patients were €18,030 [56]. Costs were higher for Dutch patients with severe TBI (range €40,680–€44,952), but these costs included rehabilitation and nursing home costs [55]. A recent systematic review reported median in-hospital costs per patient with severe TBI of €55,267 (range €2130 to €401,808) [69]. Mean hospital and healthcare charges for TBI in the USA were $36.075 and $67.224 respectively [2, 35]. Differences between studies could be explained by variation, methodological heterogeneity, differences in case mix, but also by geographical location. For example, healthcare expenditures in the USA are generally double of other high-income countries due to prices of labour, goods, pharmaceuticals and administrative costs, while healthcare utilisation was similar [45]. These issues are also reported in non-TBI literature [12, 47].

As in other studies, the main cost drivers in this current study were LOS and/or admission (66%), surgery (12%), radiology (7%), labs (4%) and other costs (11%) [2, 41, 81]. In-hospital costs were generally higher for the more severely injured patients [35, 41], with a lower GCS [24, 41, 48, 63, 69] or pupillary abnormalities [70]. Higher costs were related to an increased healthcare consumption with longer LOS [2, 48], specialised intensive care unit (ICU) treatment [2] and a more frequent use of ICP monitoring [37, 61, 81] and surgical procedures [41, 70, 80]. The presence of TBI normally increases the LOS of general admissions [62], but extracranial injury and higher overall injury severity in addition to TBI also contributed to higher in-hospital healthcare consumption and in-hospital costs [13, 57, 80]. It is however impossible to distinguish costs related to extracranial injury from costs related to TBI because these costs are too intertwined.

Compared with the hospital costs for other diseases in the Netherlands, the in-hospital costs for TBI patients were high, especially when TBI severity increased. The hospital costs for patients with ischaemic stroke (€5.328) [8], transient ischaemic attack (€2.470) [8], appendicitis (€3700) and colorectal cancer (€9.777–€19.417) [20] were lower, while costs were higher for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (€33.143) [67] or patients receiving extracorporeal life support treatment (€106.263) [44].

Strengths and limitations

The accurate calculation of in-hospital healthcare consumption and in-hospital costs of a large prospective multicentre cohort is a strength of the current study. There are also several limitations. The GCS is usually used to determine TBI severity [7], but its general applicability as a severity measure is also criticised [5]. The GCS could have been influenced by intoxication, pharmacological sedation, prehospital intubation, extracranial injury and could thereby have over- and underestimated injury severity [54]. This could have influenced study results. In a similar way, patient outcome was measured by using in-hospital mortality and GOSE. Critics state that the GOSE insufficiently accounts for the multidimensional nature of TBI outcome [32]. Unfortunately, earlier reported problems with acquiring the disease related health related quality of life outcome measure QOLIBRI resulted in too many missing data points to be useful for this manuscript [70]. Another limitation is the short-term follow-up because it is known that patient outcome and costs can change over time [17, 60, 79]. TBI patients that visited the ER but did not require hospitalisation were not included in this study. A precise calculation and comparison of costs was therefore not possible. Costs of these patients are expected to be substantially lower compared with those of admitted patients since important cost drivers (admission and surgery) are not applicable. Following the unit costs in Supplement 1 (ER, imaging, labs), the average costs are likely to be somewhere between €500 and €1.000. A reduction in number of admitted mild TBI patients, when safe and possible, might result in substantial cost savings, especially since its incidence is high.

The direct costs of TBI (all consumed resources within the health-care sector) are generally considered to be smaller than the indirect costs (loss of productivity and intangible costs) [22, 32, 43]. Because of the focus on in-hospital costs, our study results dramatically underestimate the exact total costs related to TBI [34, 56, 66]. The reported in-hospital costs are also likely to be an underestimation, despite our accurate calculations. More accurate numbers could be achieved by using hospitals’ actual cost prices, rather than approximations from guidelines or governmental organisations. These numbers were unfortunately unavailable. Including an accurate complete cost overview is however essential for future cost-effectiveness studies [11, 34, 48, 66].

Future TBI research initiatives should include the combination of long-term outcome and complete economic perspective, because this can improve the objectivity of future treatment decision-making. When striving for cost-effectiveness, people should however not forget the individual aspects of care and the social utility of providing care for severely injured patients [25].

Conclusion

Hospitalised TBI patients show substantial in-hospital healthcare consumption and high in-hospital costs, even in patients with mild TBI. These costs are likely to be an underestimation of the actual total costs after TBI. Although patients from all TBI severity categories were able to achieve full recovery, mortality and unfavourable outcome rates were high and increased with TBI severity, intracranial abnormalities, extracranial injury and surgical intervention. Future studies should focus on the long-term effectiveness of treatments in relation to a complete economic perspective.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 20 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sander van Buren for his advice on healthcare costs assessment.

Author contribution statement

JD, CM, AG, EK, WP, GR and SP made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. JD, CM, AP and GR contributed to data collection. JD analysed the data. All authors interpreted the data. JD wrote the manuscript which was critically revised by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CRF

Case report form

- CT

Computed tomography

- GCS

Glasgow Coma Score

- GOSE

Glasgow Outcome Score–Extended

- ICP

Intracranial pressure

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- LOS

Length of stay

- TBI

Traumatic brain injury

Funding information

This work was supported by the European Union seventh Framework Program (grant 602,150) for Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) and Hersenstichting Nederland (Dutch Brain Foundation) for Neurotraumatology Quality Registry (Net-QuRe).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the responsible institutional review board (METC Leiden, number P14.222).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from patients, proxies, or was deferred in accordance with the CENTER-TBI research protocol. All used informed consent procedures were approved by the responsible institutional review board.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Brain trauma

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alali AS, Burton K, Fowler RA, Naimark DM, Scales DC, Mainprize TG, Nathens AB. Economic evaluations in the diagnosis and management of traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and analysis of quality. Value Health. 2015;18:721–734. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albrecht JS, Slejko JF, Stein DM, Smith GS (2017) Treatment charges for traumatic brain injury among older adults at a trauma center. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Andelic N, Howe EI, Hellstrom T, Sanchez MF, Lu J, Lovstad M, Roe C. Disability and quality of life 20 years after traumatic brain injury. Brain Behav. 2018;8:e01018. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck B, Gantner D, Cameron P, Braaf S, Saxena M, Cooper DJ, Gabbe B (2017) Temporal trends in functional outcomes following severe traumatic brain injury: 2006-2015. J Neurotrauma. 10.1089/neu.2017.5287 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Becker A, Peleg K, Olsha O, Givon A, Kessel B. Analysis of incidence of traumatic brain injury in blunt trauma patients with Glasgow Coma Scale of 12 or less. Chin J Traumatol. 2018;21:152–155. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonow RH, Quistberg A, Rivara FP, Vavilala MS. Intensive care unit admission patterns for mild traumatic brain injury in the USA. Neurocrit Care. 2019;30:157–170. doi: 10.1007/s12028-018-0590-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brazinova A, Rehorcikova V, Taylor MS, Buckova V, Majdan M, Psota M, Peeters W, Feigin V, Theadom A, Holkovic L, Synnot A (2018) Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury in Europe: a living systematic review. J Neurotrauma. 10.1089/neu.2015.4126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Buisman LR, Tan SS, Nederkoorn PJ, Koudstaal PJ, Redekop WK. Hospital costs of ischemic stroke and TIA in the Netherlands. Neurology. 2015;84:2208–2215. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000001635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carney N, Totten AM, O'Reilly C, Ullman JS, Hawryluk GW, Bell MJ, Bratton SL, Chesnut R, Harris OA, Kissoon N, Rubiano AM, Shutter L, Tasker RC, Vavilala MS, Wilberger J, Wright DW, Ghajar J. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury, fourth edition. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:6–15. doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000001432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Cancelliere C, Côté P, Hincapié CA, Kristman VL, Holm LW, Borg J, Nygren-de Boussard C, Hartvigsen J. Systematic review of the prognosis after mild traumatic brain injury in adults: cognitive, psychiatric, and mortality outcomes: results of the international collaboration on mild traumatic brain injury prognosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:S152–S173. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.08.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen A, Bushmeneva K, Zagorski B, Colantonio A, Parsons D, Wodchis WP. Direct cost associated with acquired brain injury in Ontario. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:76. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cnossen MC, Polinder S, Andriessen TM, van der Naalt J, Haitsma I, Horn J, Franschman G, Vos PE, Steyerberg EW, Lingsma H. Causes and consequences of treatment variation in moderate and severe traumatic brain injury: a multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:660–669. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000002263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis KL, Joshi AV, Tortella BJ, Candrilli SD. The direct economic burden of blunt and penetrating trauma in a managed care population. J Trauma. 2007;62:622–629. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318031afe3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Koning ME, Scheenen ME, Van Der Horn HJ, Spikman JM, Van Der Naalt J. From ‘'miserable minority’ to the ‘fortunate few’: the other end of the mild traumatic brain injury spectrum. Brain Inj. 2018;32:540–543. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2018.1431844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dewan MC, Rattani A, Gupta S, Baticulon RE, Hung YC, Punchak M, Agrawal A, Adeleye AO, Shrime MG, Rubiano AM, Rosenfeld JV, Park KB (2018) Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg:1–18. 10.3171/2017.10.jns17352 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Einarsen CE, van der Naalt J, Jacobs B, Follestad T, Moen KG, Vik A, Haberg AK, Skandsen T. Moderate traumatic brain injury: clinical characteristics and a prognostic model of 12-month outcome. World Neurosurg. 2018;114:e1199–e1210. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.03.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forslund MV, Perrin PB, Roe C, Sigurdardottir S, Hellstrom T, Berntsen SA, Lu J, Arango-Lasprilla JC, Andelic N. Global outcome trajectories up to 10 years after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Front Neurol. 2019;10:219. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fountain DM, Kolias AG, Lecky FE, Bouamra O, Lawrence T, Adams H, Bond SJ, Hutchinson PJ. Survival trends after surgery for acute subdural hematoma in adults over a 20-year period. Ann Surg. 2017;265:590–596. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000001682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frontera JA, Egorova N, Moskowitz AJ. National trend in prevalence, cost, and discharge disposition after subdural hematoma from 1998-2007. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1619–1625. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182186ed6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Govaert JA, van Dijk WA, Fiocco M, Scheffer AC, Gietelink L, Wouters MW, Tollenaar RA. Nationwide outcomes measurement in colorectal cancer surgery: improving quality and reducing costs. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grauwmeijer E, Heijenbrok-Kal MH, Peppel LD, Hartjes CJ, Haitsma IK, de Koning I, Ribbers GM. Cognition, health-related quality of life, and depression ten years after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective cohort study. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35:1543–1551. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jacobi F, Allgulander C, Alonso J, Beghi E, Dodel R, Ekman M, Faravelli C, Fratiglioni L, Gannon B, Jones DH, Jennum P, Jordanova A, Jonsson L, Karampampa K, Knapp M, Kobelt G, Kurth T, Lieb R, Linde M, Ljungcrantz C, Maercker A, Melin B, Moscarelli M, Musayev A, Norwood F, Preisig M, Pugliatti M, Rehm J, Salvador-Carulla L, Schlehofer B, Simon R, Steinhausen HC, Stovner LJ, Vallat JM, Van den Bergh P, van Os J, Vos P, Xu W, Wittchen HU, Jonsson B, Olesen J. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:718–779. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hakkaart-van Roijen L vdLN, Bouwmans CAM, Kanters TA, Tan SS. Kostenhandleiding: Methodologie van kostenonderzoek en referentieprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. Zorginstituut Nederland. Geactualiseerde versie 2015. https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/binaries/zinl/documenten/publicatie/2016/02/29/richtlijn-voor-het-uitvoeren-van-economische-evaluaties-in-de-gezondheidszorg/Richtlijn+voor+het+uitvoeren+van+economische+evaluaties+in+de+gezondheidszorg+%28verdiepingsmodules%29.pdf. Accessed 30 Sep 2019

- 24.Ho KM, Honeybul S, Lind CR, Gillett GR, Litton E. Cost-effectiveness of decompressive craniectomy as a lifesaving rescue procedure for patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2011;71:1637–1644. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31823a08f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honeybul S, Gillett GR, Ho KM, Lind CR. Neurotrauma and the rule of rescue. J Med Ethics. 2011;37:707–710. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2011-100081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isokuortti H, Iverson GL, Silverberg ND, Kataja A, Brander A, Ohman J, Luoto TM. Characterizing the type and location of intracranial abnormalities in mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2018;129:1588–1597. doi: 10.3171/2017.7.Jns17615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keita S, Kazuhiro S, Jun T, Hidenori H, Akio M (2019) In-hospital mortality and length of hospital stay with craniotomy versus craniectomy for acute subdural hemorrhage: a multicenter, propensity score–matched analysis. J Neurosurgery:1–10. 10.3171/2019.4.JNS182660 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Krishnamoorthy V, Vavilala MS, Mills B, Rowhani-Rahbar A. Demographic and clinical risk factors associated with hospital mortality after isolated severe traumatic brain injury: a cohort study. J Intensive Care. 2015;3:46. doi: 10.1186/s40560-015-0113-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawrence T, Helmy A, Bouamra O, Woodford M, Lecky F, Hutchinson PJ. Traumatic brain injury in England and Wales: prospective audit of epidemiology, complications and standardised mortality. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012197. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu J, Roe C, Aas E, Lapane KL, Niemeier J, Arango-Lasprilla JC, Andelic N. Traumatic brain injury: methodological approaches to estimate health and economic outcomes. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:1925–1933. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maas AI, Menon DK, Steyerberg EW, Citerio G, Lecky F, Manley GT, Hill S, Legrand V, Sorgner A. Collaborative European NeuroTrauma effectiveness research in traumatic brain injury (CENTER-TBI): a prospective longitudinal observational study. Neurosurgery. 2015;76:67–80. doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000000575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maas AIR, Menon DK, Adelson PD, Andelic N, Bell MJ, Belli A, Bragge P, Brazinova A, Buki A, Chesnut RM, Citerio G, Coburn M, Cooper DJ, Crowder AT, Czeiter E, Czosnyka M, Diaz-Arrastia R, Dreier JP, Duhaime AC, Ercole A, van Essen TA, Feigin VL, Gao G, Giacino J, Gonzalez-Lara LE, Gruen RL, Gupta D, Hartings JA, Hill S, Jiang JY, Ketharanathan N, Kompanje EJO, Lanyon L, Laureys S, Lecky F, Levin H, Lingsma HF, Maegele M, Majdan M, Manley G, Marsteller J, Mascia L, McFadyen C, Mondello S, Newcombe V, Palotie A, Parizel PM, Peul W, Piercy J, Polinder S, Puybasset L, Rasmussen TE, Rossaint R, Smielewski P, Soderberg J, Stanworth SJ, Stein MB, von Steinbuchel N, Stewart W, Steyerberg EW, Stocchetti N, Synnot A, Te Ao B, Tenovuo O, Theadom A, Tibboel D, Videtta W, Wang KKW, Williams WH, Wilson L, Yaffe K. Traumatic brain injury: integrated approaches to improve prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:987–1048. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(17)30371-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Majdan M, Plancikova D, Brazinova A, Rusnak M, Nieboer D, Feigin V, Maas A. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injuries in Europe: a cross-sectional analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2016;1:e76–e83. doi: 10.1016/s2468-2667(16)30017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Majdan M, Plancikova D, Maas A, Polinder S, Feigin V, Theadom A, Rusnak M, Brazinova A, Haagsma J. Years of life lost due to traumatic brain injury in Europe: a cross-sectional analysis of 16 countries. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marin JR, Weaver MD, Mannix RC. Burden of USA hospital charges for traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2017;31:24–31. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2016.1217351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marincowitz C, Lecky FE, Townend W, Borakati A, Fabbri A, Sheldon TA. The risk of deterioration in GCS13-15 patients with traumatic brain injury identified by computed tomography imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35:703–718. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martini RP, Deem S, Yanez ND, Chesnut RM, Weiss NS, Daniel S, Souter M, Treggiari MM. Management guided by brain tissue oxygen monitoring and outcome following severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2009;111:644–649. doi: 10.3171/2009.2.Jns08998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McIntyre A, Mehta S, Aubut J, Dijkers M, Teasell RW. Mortality among older adults after a traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis. Brain Inj. 2013;27:31–40. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2012.700086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McIntyre A, Mehta S, Janzen S, Aubut J, Teasell RW. A meta-analysis of functional outcome among older adults with traumatic brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013;32:409–414. doi: 10.3233/nre-130862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore L, Stelfox HT, Evans D, Hameed SM, Yanchar NL, Simons R, Kortbeek J, Bourgeois G, Clement J, Lauzier F, Turgeon AF. Hospital and intensive care unit length of stay for injury admissions: a pan-Canadian cohort study. Ann Surg. 2018;267:177–182. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000002036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morris S, Ridley S, Lecky FE, Munro V, Christensen MC. Determinants of hospital costs associated with traumatic brain injury in England and Wales. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:499–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moskowitz E, Melendez CI, Dunn J, Khan AD, Gonzalez R, Liebscher S, Schroeppel TJ. Long-term effects of decompressive craniectomy on functional outcomes after traumatic brain injury: a multicenter study. Am Surg. 2018;84:1314–1318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olesen J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Wittchen HU, Jonsson B. The economic cost of brain disorders in Europe. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:155–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oude Lansink-Hartgring A, van den Hengel B, van der Bij W, Erasmus ME, Mariani MA, Rienstra M, Cernak V, Vermeulen KM, van den Bergh WM. Hospital costs of extracorporeal life support therapy. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:717–723. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000001477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA. 2018;319:1024–1039. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piccinini A, Lewis M, Benjamin E, Aiolfi A, Inaba K, Demetriades D. Intracranial pressure monitoring in severe traumatic brain injuries: a closer look at level 1 trauma centers in the United States. Injury. 2017;48:1944–1950. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Polinder S, Meerding WJ, van Baar ME, Toet H, Mulder S, van Beeck EF. Cost estimation of injury-related hospital admissions in 10 European countries. J Trauma. 2005;59:1283–1290. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000195998.11304.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ponsford JL, Spitz G, Cromarty F, Gifford D, Attwood D. Costs of care after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:1498–1505. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raj R, Bendel S, Reinikainen M, Hoppu S, Laitio R, Ala-Kokko T, Curtze S, Skrifvars MB. Costs, outcome and cost-effectiveness of neurocritical care: a multi-center observational study. Crit Care. 2018;22:225. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2151-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robertsen A, Førde R, Skaga NO, Helseth E. Treatment-limiting decisions in patients with severe traumatic brain injury in a Norwegian regional trauma center. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2017;25:44–44. doi: 10.1186/s13049-017-0385-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenfeld JV, Maas AI, Bragge P, Morganti-Kossmann MC, Manley GT, Gruen RL. Early management of severe traumatic brain injury. Lancet. 2012;380:1088–1098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60864-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruet A, Bayen E, Jourdan C, Ghout I, Meaude L, Lalanne A, Pradat-Diehl P, Nelson G, Charanton J, Aegerter P, Vallat-Azouvi C, Azouvi P. A detailed overview of long-term outcomes in severe traumatic brain injury eight years post-injury. Front Neurol. 2019;10:120. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rush B, Rousseau J, Sekhon MS, Griesdale DE. Craniotomy versus craniectomy for acute traumatic subdural hematoma in the United States: a national retrospective cohort analysis. World Neurosurg. 2016;88:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salottolo K, Carrick M, Levy AS, Morgan BC, Mains CW, Slone DS, Bar-Or D. Aggressive operative neurosurgical management in patients with extra-axial mass lesion and Glasgow Coma Scale of 3 is associated with survival benefit: a propensity matched analysis. Injury. 2016;47:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saltzherr TP, Goslings JC, Bakker FC, Beenen LFM, Olff M, Meijssen K, Asselman FF, Reitsma JB, Dijkgraaf MGW. Cost-effectiveness of trauma CT in the trauma room versus the radiology department: the REACT trial. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:148–155. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2593-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scholten AC, Haagsma JA, Panneman MJ, van Beeck EF, Polinder S. Traumatic brain injury in the Netherlands: incidence, costs and disability-adjusted life years. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spitz G, McKenzie D, Attwood D, Ponsford JL. Cost prediction following traumatic brain injury: model development and validation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:173–180. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-309479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stein SC, Georgoff P, Meghan S, Mizra K, Sonnad SS. 150 years of treating severe traumatic brain injury: a systematic review of progress in mortality. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1343–1353. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steyerberg EW, Wiegers E, Sewalt C, Buki A, Citerio G, De Keyser V, Ercole A, Kunzmann K, Lanyon L, Lecky F, Lingsma H, Manley G, Nelson D, Peul W, Stocchetti N, von Steinbuchel N, Vande Vyvere T, Verheyden J, Wilson L, Maas AIR, Menon DK. Case-mix, care pathways, and outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury in CENTER-TBI: a European prospective, multicentre, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:923–934. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(19)30232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stocchetti N, Zanier ER. Chronic impact of traumatic brain injury on outcome and quality of life: a narrative review. Crit Care. 2016;20:148. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1318-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Su SH, Wang F, Hai J, Liu NT, Yu F, Wu YF, Zhu YH. The effects of intracranial pressure monitoring in patients with traumatic brain injury. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tardif PA, Moore L, Boutin A, Dufresne P, Omar M, Bourgeois G, Bonaventure PL, Kuimi BL, Turgeon AF. Hospital length of stay following admission for traumatic brain injury in a Canadian integrated trauma system: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Injury. 2017;48:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2016.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Te Ao B, Brown P, Tobias M, Ameratunga S, Barker-Collo S, Theadom A, McPherson K, Starkey N, Dowell A, Jones K, Feigin VL. Cost of traumatic brain injury in New Zealand: evidence from a population-based study. Neurology. 2014;83:1645–1652. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000000933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tien HC, Cunha JR, Wu SN, Chughtai T, Tremblay LN, Brenneman FD, Rizoli SB. Do trauma patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 3 and bilateral fixed and dilated pupils have any chance of survival? J Trauma. 2006;60:274–278. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000197177.13379.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tuominen R, Joelsson P, Tenovuo O. Treatment costs and productivity losses caused by traumatic brain injuries. Brain Inj. 2012;26:1697–1701. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2012.722256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van der Linden N, Bongers ML, Coupe VM, Smit EF, Groen HJ, Welling A, Schramel FM, Uyl-de Groot CA. Costs of non-small cell lung cancer in the Netherlands. Lung Cancer. 2016;91:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van der Naalt J, Timmerman ME, de Koning ME, van der Horn HJ, Scheenen ME, Jacobs B, Hageman G, Yilmaz T, Roks G, Spikman JM. Early predictors of outcome after mild traumatic brain injury (UPFRONT): an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:532–540. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(17)30117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Dijck J, Dijkman MD, Ophuis RH, de Ruiter GCW, Peul WC, Polinder S. In-hospital costs after severe traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and quality assessment. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0216743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van Dijck J, van Essen TA, Dijkman MD, Mostert CQB, Polinder S, Peul WC, de Ruiter GCW (2019) Functional and patient-reported outcome versus in-hospital costs after traumatic acute subdural hematoma (t-ASDH): a neurosurgical paradox? Acta Neurochir. 10.1007/s00701-019-03878-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.van Dijck JT, Reith FC, van Erp IA, van Essen TA, Maas AI, Peul WC, de Ruiter GC. Decision making in very severe traumatic brain injury (Glasgow Coma Scale 3-5): a literature review of acute neurosurgical management. J Neurosurg Sci. 2018;62:153–177. doi: 10.23736/s0390-5616.17.04255-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van Leeuwen N, Lingsma HF, Perel P, Lecky F, Roozenbeek B, Lu J, Shakur H, Weir J, Steyerberg EW, Maas AI. Prognostic value of major extracranial injury in traumatic brain injury: an individual patient data meta-analysis in 39,274 patients. Neurosurgery. 2012;70:811–818. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318235d640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vande Vyvere T, Wilms G, Claes L, Martin Leon F, Nieboer D, Verheyden J, van den Hauwe L, Pullens P, Maas AIR, Parizel PM. Central versus local radiological reading of acute computed tomography characteristics in multi-center traumatic brain injury research. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36:1080–1092. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.6061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ventura T, Harrison-Felix C, Carlson N, Diguiseppi C, Gabella B, Brown A, Devivo M, Whiteneck G. Mortality after discharge from acute care hospitalization with traumatic brain injury: a population-based study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.08.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Volovici V, Steyerberg EW, Cnossen MC, Haitsma IK, Dirven CMF, Maas AIR, Lingsma HF. Evolution of evidence and guideline recommendations for the medical management of severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36:3183–3189. doi: 10.1089/neu.2019.6474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Prev Med. 2007;45:247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Watanabe T, Kawai Y, Iwamura A, Maegawa N, Fukushima H, Okuchi K. Outcomes after traumatic brain injury with concomitant severe extracranial injuries. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2018;58:393–399. doi: 10.2176/nmc.oa.2018-0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wilson JT, Pettigrew LE, Teasdale GM. Structured interviews for the Glasgow Outcome Scale and the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale: guidelines for their use. J Neurotrauma. 1998;15:573–585. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wilson L, Stewart W, Dams-O'Connor K, Diaz-Arrastia R, Horton L, Menon DK, Polinder S. The chronic and evolving neurological consequences of traumatic brain injury. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:813–825. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(17)30279-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yuan Q, Liu H, Wu X, Sun Y, Yao H, Zhou L, Hu J. Characteristics of acute treatment costs of traumatic brain injury in eastern China—a multi-centre prospective observational study. Injury. 2012;43:2094–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2012.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zapata-Vazquez RE, Alvarez-Cervera FJ, Alonzo-Vazquez FM, Garcia-Lira JR, Granados-Garcia V, Perez-Herrera NE, Medina-Moreno M. Cost effectiveness of intracranial pressure monitoring in pediatric patients with severe traumatic brain injury: a simulation modeling approach. Value Health Reg Issues. 2017;14:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2017.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zorgautoriteit Nederland. Open data van de Nederlandse Zorgautoriteit http://www.opendisdata.nl. Accessed 29 March 2019

- 83.Zorgautoriteit Nederland. Tarieventabel DBC-zorgproducten en overige producten - per 1 januari 2012 (PUC_12710_22). https://puc.overheid.nl/nza/doc/PUC_12710_22/1/. Accessed Accessed 29 Sep 2019

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 20 kb)