Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has produced a significant health burden worldwide, especially in patients with cardiovascular comorbidities. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to assess the impact of underlying cardiovascular comorbidities and acute cardiac injury on in-hospital mortality risk.

Methods

PubMed, Embase and Web of Science were searched for publications that reported the relationship of underlying cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension and myocardial injury with in-hospital fatal outcomes in patients with COVID-19. The ORs were extracted and pooled. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were performed to explore the potential sources of heterogeneity.

Results

A total of 10 studies were enrolled in this meta-analysis, including eight studies for CVD, seven for hypertension and eight for acute cardiac injury. The presence of CVD and hypertension was associated with higher odds of in-hospital mortality (unadjusted OR 4.85, 95% CI 3.07 to 7.70; I2=29%; unadjusted OR 3.67, 95% CI 2.31 to 5.83; I2=57%, respectively). Acute cardiac injury was also associated with a higher unadjusted odds of 21.15 (95% CI 10.19 to 43.94; I2=71%).

Conclusion

COVID-19 patients with underlying cardiovascular comorbidities, including CVD and hypertension, may face a greater risk of fatal outcomes. Acute cardiac injury may act as a marker of mortality risk. Given the unadjusted results of our meta-analysis, future research are warranted.

Keywords: cardiac risk factors and prevention, epidemiology, global health, meta-analysis

Introduction

In the past two decades, the pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2002 and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2012 have taken severe death tolls worldwide, with 916 and 800 deaths, respectively.1 In late 2019, another virus with lethal respiratory infection potential identified as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2) emerged and heralded another global pandemic.2 Since the outbreak in Wuhan, more than 200 countries and regions have reported confirmed cases. The WHO coined COVID-19 to describe ‘coronavirus disease 2019’ and declared this outbreak as a public health emergency of international concern.3 As of 24 April 2020, there have been nearly 2 750 000 infections and over 192 000 deaths worldwide.

Within less than 6 months, COVID-19 has registered a mortality record that is higher than that of SARS and MERS combined.4 5 Because of the overwhelming fatality cases caused by COVID-19, much concern has been raised to determine the risk factors for poor prognosis, such as advanced age and male sex.3 6 Previous research has reported that patients with underlying cardiovascular disease (CVD) were prone to viral infection and also had a greater risk of developing severe cases and being admitted to intensive care unit.7 8 SARS-CoV-2 can attack the respiratory system by targeting ACE2. However, with the high tissue-specificity of ACE2 expression in the cardiovascular system, cardiomyocytes may be particularly prone to damage.9 Several studies have reported a high incidence of elevated cardiac troponin in hospitalised patients, especially in those in critical conditions.10 11 Thus, patients with CVD complications may have poor prognosis when infected with SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, here we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on the available evidence to evaluate the association between underlying CVD and incident cardiac injury with in-hospital mortality risk in patients with COVID-19.

Methods

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement12 and the Meta analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement.13

Search strategy

A comprehensive search was performed in PubMed, Embase and Web of Science databases from 1 January 2020 to 14 April 2020. The following search terms were included: ‘coronavirus’, ‘COVID-19’, ‘2019-nCoV’, ‘SARS-CoV-2’, ‘cardiovascular disease’, ‘coronary heart disease’, ‘hypertension’, ‘cardiac injury’, ‘myocardia injury’, ‘mortality’, ‘death’ and ‘fatality’. In addition, the reference lists of relevant articles were reviewed for potential studies.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included for the meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: (1) exposure factor: CVD (coronary heart disease, cardiac disease and chronic cardiac disease), hypertension or acute cardiac injury; (2) outcome interest: in-hospital mortality; and (3) study population: adult patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. To avoid duplication, we contacted the authors whose studies were conducted in the same hospital. If the same batch of patients were enrolled or no specific information identifying the patients could be provided, study with the largest sample size was included.

Study selections

Two researchers (XL and BG) independently screened the search results by titles and abstracts. Any potentially relevant studies were retrieved with full texts for further evaluation. Two authors (XL and BG) independently identified the eligible studies based on inclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with another researcher (TS).

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two researchers (XL and BG) independently extracted data from the enrolled studies via a preset standardised form. The following information was extracted: first author, publication year, study design, location, patients enrolled period, age, sex, prevalence of comorbidities, exposure factors and level of adjustment. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale terms,14 with total score of nine stars, were applied to evaluate the quality of case series studies or cohort studies separately. The studies with 7 points or more were considered of high quality.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using Stata V.12.0 software. The unadjusted ORs with 95% CIs were calculated as the common risk estimates and then were pooled due to the limited data on multivariable adjusted outcomes. The heterogeneity among studies was evaluated by Cochran’s Q-statistic and I2 test. If I2 ≤50%, a fixed effects model was adopted; otherwise, a random effects model was applied to meta-analysis. Meta-regression analysis was performed to test the potential sources of heterogeneity among studies. Sensitivity analyses were also performed by omitting one study at a time to evaluate the influence of individual study on the pooled results. Publication bias was evaluated by visual inspection of asymmetry in funnel plots.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting, dissemination plans of our research.

Results

Study selection

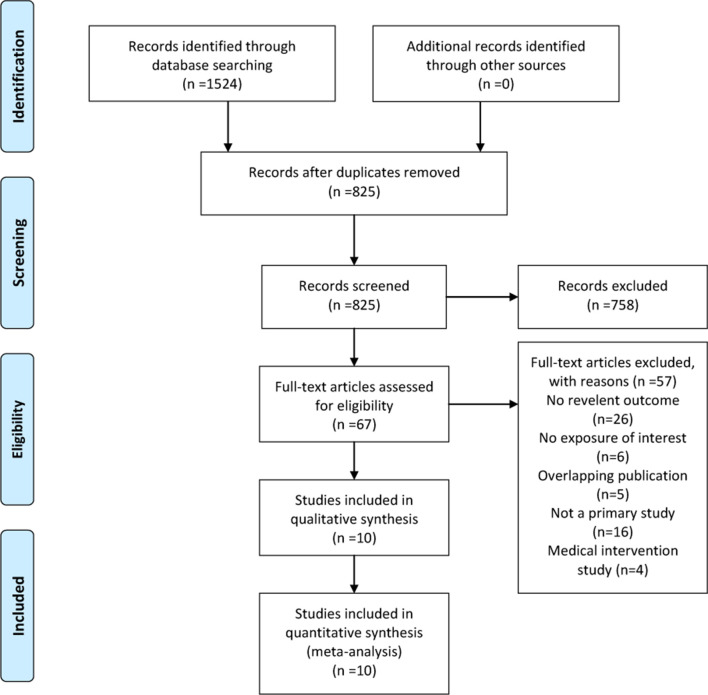

The initial database search yielded 1524 studies (figure 1). After removing duplicate publications, 825 studies were left and screened by title and abstract, and we identified 67 articles for full-text review. Of these, 57 studies were excluded due to no relevant outcome, no exposure of interest, duplicated publication, not a primary study or medical intervention study (online supplementary file 1). No additional studies met the inclusion criteria from screening reference lists. When several studies were published by the same institution, the authors were contacted to ensure that no overlapping cohorts were analysed as separate studies. Altogether, 10 studies comprising 3118 patients were included in this meta-analysis.15–24

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses flow diagram of study selection.

heartjnl-2020-317062supp001.pdf (287KB, pdf)

Study characteristics

The main characteristics of the included studies are summarised in table 1. Of all 10 studies, two were case series design15 16 and the remaining eight were cohort studies.17–24 All studies were conducted in Wuhan, China, except for one study that enrolled patients nationwide.17 The patients were all accrued from the end of December 2019 to February 2020. The mean age ranged from 49 years old17 to 6819 years old and the proportion of male patients ranged from 45%22 to 67%.21 The prevalence of CVD and hypertension ranged from 4%17 to 15%18 and from 17%17 to 44%,19 respectively, and from 15%24 to 44%15 of patients experienced cardiac injury during hospitalisation (table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the included studies

| Author, year | Study design | Location | Patients enrol period | Number of patients | Type of exposure | Adjustment level | NOS |

| Chen, 202015 | Case series | Tongji Hospital, Wuhan, China. |

13 January 2020– 28 February 2020 |

274 | Hypertension. Cardiovascular disease. Acute cardiac injury. |

None. | 6 |

| Deng, 202016 | Case series | Hankou and Caidian branch of Tongji Hospital; Hankou branch of Central Hospital, Wuhan, China. |

1 January 2020–21 February 2020 | 225 | Hypertension. Cardiac disease. Acute cardiac injury. |

None. | 6 |

| Guan, 202017 | Cohort | Nationwide, China. | 11 December 2019–31 January 2020 | 1590 | Hypertension. Cardiovascular disease. |

Multivariable-adjusted for hypertension. | 7 |

| Guo, 202018 | Cohort | Seventh Hospital, Wuhan, China. |

23 January 2020–23 February 2020 |

187 | Cardiac injury. | None. | 7 |

| He, 202019 | Cohort | Zhongfa Xincheng Hospital, Wuhan, China. | 3 February 2020– 24 February 2020 |

54 | Hypertension. Coronary heart disease. Acute cardiac injury. |

None. | 7 |

| ShiB, 202020 | Cohort | Renmin Hospital, Wuhan, China. |

20 January 2020– 10 February 2020 |

416 | Cardiac injury. | Multivariable adjusted. | 8 |

| Yang, 202021 | Cohort | Jin Yin-tan hospital, Wuhan, China. |

24 Dember 2019–26 January 2020 | 52 | Chronic cardiac disease. Cardiac injury. |

None. | 7 |

| Yuan, 202022 | Cohort | Central Hospital, Wuhan, China. |

1 January 2020–25 January 2020 | 27 | Cardiac disease. Cardiac injury. |

None. | 7 |

| Zhou, 202023 | Cohort | Jinyintan Hospital and Pulmonary Hospital, Wuhan, China. |

29 December 2019–31 January 2020 | 191 | Hypertension. Coronary heart disease. Acute cardiac injury. |

Multivariable-adjusted for coronary heart disease. | 8 |

| Cao, 202024 | Cohort | Zhongnan Hospital, Wuhan, China. |

3 January 2020–1 February 2020 | 102 | Hypertension. Cardiovascular disease. Acute cardiac injury. |

None. | 7 |

NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients in included studies

| Author, year | Total number | Mean age (years) | Sex (male,%) | Cardiovascular disease (%) | Hypertension (%) | Cardiac injury (%) | ||||||

| Death | Alive | Death | Alive | Death | Alive | Death | Alive | Death | Alive | Death | Alive | |

| Chen, 202015 | 113 | 161 | 68 | 51 | 73 | 55 | 15 | 4 | 48 | 24 | 77 | 17 |

| Deng, 202016 | 109 | 116 | 69 | 40 | 67 | 44 | 11.9 | 3.4 | 36.7 | 15.5 | 59.6 | 0.9 |

| Guan, 202017 | 50 | 1540 | 48.9 | 57.3 | 16.0 | 2.7 | 56.0 | 15.6 | NA | NA | ||

| Guo, 202018 | 43 | 144 | 58.5 | 48.7 | 15.5 | 32.6 | 27.8 | |||||

| He, 202019 | 26 | 28 | 70.0 | 66.5 | 61.5 | 64.3 | 19.2 | 10.7 | 46.2 | 42.9 | 69.2 | 21.4 |

| Shi, 202020 | 57 | 359 | 64 | 49.3 | 14.7 | 30.5 | 19.7 | |||||

| Yang, 202021 | 32 | 20 | 64.6 | 51.9 | 66 | 70 | 9 | 10 | NA | NA | 28 | 15 |

| Yuan, 202022 | 10 | 17 | 68 | 55 | 40 | 47 | 30 | 0 | 50 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Zhou, 202023 | 54 | 137 | 69 | 52 | 70 | 59 | 24 | 1 | 48 | 23 | 59 | 1 |

| Cao, 202024 | 17 | 85 | 72 | 53 | 76.5 | 47.1 | 17.6 | 2.4 | 64.7 | 20.0 | 70.6 | 3.5 |

NA, not available.

Primary outcomes

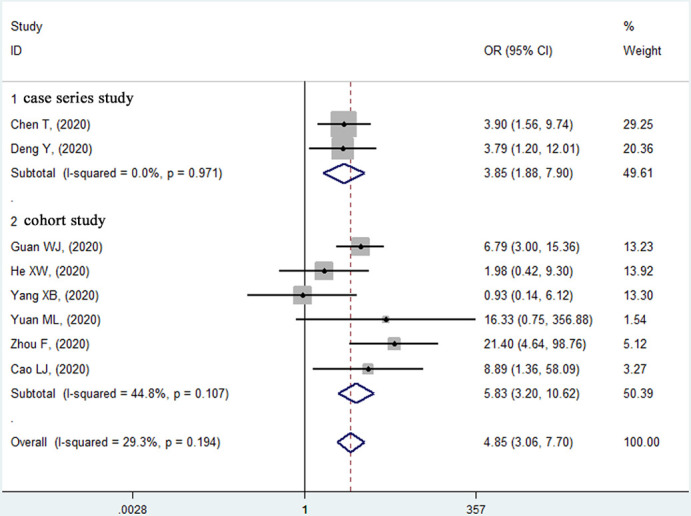

Eight studies15–17 19 21–24 reported the relationship between underlying CVD and in-hospital mortality risk (2515 patients and 127 deaths) in unadjusted model. Five studies15–17 23 24 consistently revealed a significantly higher death risk in the CVD group and the remaining three studies19 21 22 reported no significant relationship between CVD and in-hospital mortality (figure 2). Overall, the summary estimate demonstrated that patients with CVD had an approximately fivefold higher risk of mortality compared with non-CVD patients (unadjusted OR 4.85, p<0.001; 95% CI 3.06 to 7.70). The heterogeneity across the studies was non-significant (I2=29.3%, p=0.194).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the relationship between pre-existing cardiovascular disease and in-hospital mortality risk in patients with COVID-19.

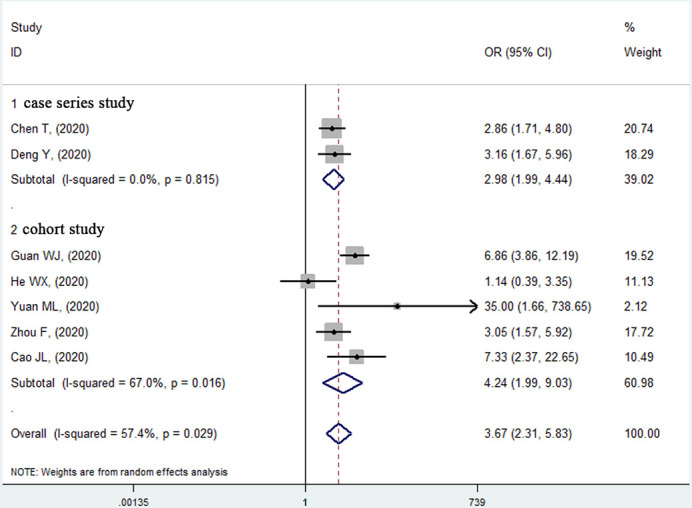

Seven studies15–17 22–24 (2463 patients and 535 deaths) were included for the pre-existing hypertension and in-hospital mortality analysis with unadjusted ORs. Six studies15–17 22–24 reported a significantly higher mortality risk in patients with previous hypertension, and the remaining study19 showed no significant association (figure 3). The pooled unadjusted effect of hypertension on mortality risk was 3.67 (95% CI 2.31 to 5.83, p<0.001) with moderate heterogeneity (I2=57.4%, p=0.029).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the relationship between previous hypertension and in-hospital mortality risk in patients with COVID-19.

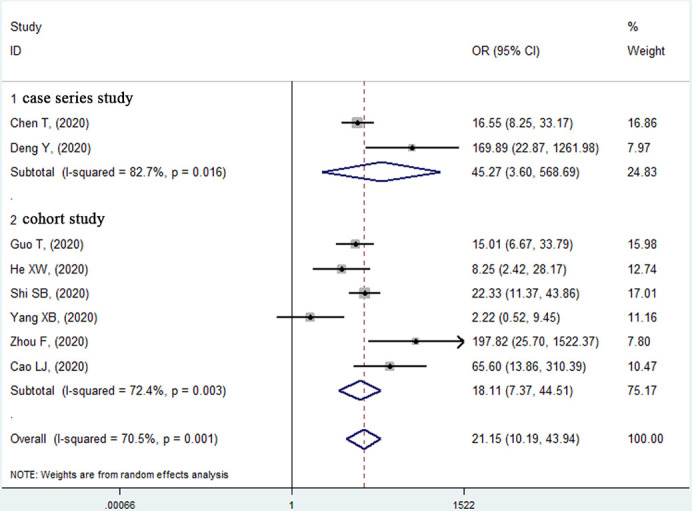

For cardiac injury, all eight studies15 16 18–21 23 24 (1429 patients and 374 deaths) except one21 reported that acute cardiac injury was significantly associated with a high mortality risk in unadjusted model (figure 4). The pooled effect of these studies (unadjusted OR 21.15, 95% CI 10.19 to 43.94, p<0.001; heterogeneity: I2=70.5%, p=0.001) showed that patients with elevated troponin levels had a significant higher mortality risk than those with normal troponin levels.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the relationship between acute cardiac injury and in-hospital mortality risk in patients with COVID-19.

Publication bias, sensitivity analysis and meta-regression

Visual inspection of the funnel plots did not show significant asymmetry (online supplementary file 2). Sensitivity analyses were conducted by systematically excluding one study at a time, and the results remained consistent with the primary analyses (online supplementary file 3). To explore potential sources of heterogeneity, meta-regression was applied to test the influence of study design, sample size, mean age and male proportion. None of these factors contributed significantly to the observed heterogeneity (online supplementary file 4).

heartjnl-2020-317062supp002.pdf (128.9KB, pdf)

heartjnl-2020-317062supp003.pdf (85.7KB, pdf)

heartjnl-2020-317062supp004.pdf (81.6KB, pdf)

Discussion

Our study evaluated the impact of underlying CVD, hypertension and acute cardiac injury on in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19. Our results showed a positive association between previous CVD and hypertension with fatal outcomes, with unadjusted ORs and 95% CIs of 4.85 (3.06 to 7.70) and 3.67 (2.31 to 5.83) and a significant relationship between acute cardiac injury and in-hospital mortality (unadjusted OR 21.15, 95% CI 10.19 to 43.94).

The 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) is a single-strand RNA virus that shares several similarities with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV in genetic sequencing and clinical presentation but is equipped with a more robust capacity for human-to-human transmission.25 26 From the outset, the capacity of 2019-nCoV to spread and infect people in Wuhan, China, was alarming, and the infection has rippled throughout the rest of the world, causing severe morbidity and mortality.27 Therefore, there is a pressing need to identify risk factors for poor prognosis among patients with COVID-19.

Patients with cardiovascular comorbidities were found to be more vulnerable to coronavirus infection and may have poor prognoses.4 Previous meta-analyses systematically tested the relationship between CVD and severity of the disease but with non-uniform definitions of clinical outcome.28 29 The meta-analysis by Zuin et al 30 included three studies and reported a positive association between hypertension and mortality risk in patients with COVID-19. Our study reinforced their conclusion and found that patients with CVD history also had an almost fivefold higher risk of mortality comparing with non-CVD patients. However, since our results were obtained using unadjusted ORs, the exact role of CVD in the risk stratification of patients with COVID-19 is still undetermined. There may be several mechanisms that account for the high mortality risk of COVID-19 patients with CVD history. First, patients with underlying CVD are more likely to decline into an unstable haemodynamic status when infected with 2019-nCoV.31 Severe pneumonia places a considerable workload on cardiac ventricles, which may exacerbate pre-existing left ventricular dysfunction, even causing cardiogenic shock.4 Second, inflammatory reactions caused by 2019-nCoV infection might convert chronic coronary artery disease into acute coronary syndrome.32 33 A profound systemic inflammation wave along with local inflammatory infiltration may lead to a hypercoagulative state and atherosclerotic plaque rupture, which may culminate in thrombotic events.23 Third, the priority of treatments, in favour of limiting nosocomial viral transmission while neglecting other medical issues, might predispose CVD patients to unfavourable clinical outcomes. The current interim guidelines suggest that patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction should consider thrombolysis first in the COVID-19 era.34 Severe adverse effects such as cerebral haemorrhage and insufficient and undesignated coronary revascularisation caused by thrombolysis can increase the risk of death.

Acute cardiac injury is commonly recorded in patients with COVID-19.35 The incidence of cardiac injury among our enrolled studies ranged from 15% to 44%, which was higher than the prevalence of CVD (5%–15%). This suggested that 2019-nCoV might attack cardiomyocytes through different pathways, other than exacerbating the already compromised cardiovascular system. 2019-nCoV infection may lead to cardiac injury secondary to conditions causing oxygen supplement insufficiency, such as severe pneumonia, anaemia, hypotension and bradycardia. Furthermore, by attacking myocardium via the highly expressed ACE2 directly, 2019-nCoV precipitated the release of cytokine and chemokine waves and caused myocardial inflammation, even leading to fulminant myocarditis in severe cases.31 36 Meanwhile, our results complied with Guo et al,18 who reported that the death risk of cardiac injury was much higher than that of pre-existing CVD. Their study revealed that patients with copresence of CVD and cardiac injury registered the highest mortality rate of 69.4%, while those with only underlying CVD had a relatively favourable prognosis (mortality rate of 13.3%). Furthermore, elevated troponin was reported to be associated with a high risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome, hepatic dysfunction and acute renal injury in patients with COVID-19.18 37 The study by Shi et al 20 demonstrated that elevated troponin was an independent risk factor for death after adjusting other confounders.20 Thus, this index may be considered as a biomarker to predict the mortality risk of patients with COVID-19. More studies are warranted to confirm this finding and provide probable suggestions on the risk stratification of patients with COVID-19.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the association of underlying CVD and acute cardiac injury with mortality risk in patients with COVID-19. This meta-analysis may provide insights into the prognosis stratification of patients with COVID-19. However, there are some important limitations that should be mentioned. First, our meta-analysis was conducted on unadjusted ORs due to the limited data on multivariable-adjusted outcomes. The observed association of CVD and cardiac injury with mortality might be confounded by other risk factors, such as advanced age, and cofounder adjustment may distort our meta-analysis results towards a less significant risk. Thus, large cohort studies with multivariate analysis are needed to provide more evidence on this issue. Second, our study could not determine the causal effects of cardiovascular comorbidities on mortality due to the inherent limitations of observational studies. Future studies aiming to investigate this causal association are warranted. Third, the heterogeneity among studies for cardiac injury was significantly high, which may be caused by the study design and patient inclusion criteria. However, the meta-regression exploring the potential sources did not find significant results, and the results remained consistent in sensitivity analyses. Finally, most of the studies enrolled were conducted in Wuhan, China. Therefore, these results should be treated with caution when extrapolated to other populations. Since Wuhan was the initial epicentre of the outbreak, these early evidence may provide clinical implications and insights for researchers and clinicians in other parts of the world.

Conclusion

COVID-19 patients with underlying cardiovascular comorbidities, including CVD and hypertension, may face a greater risk of fatal outcomes. Acute cardiac injury may act as a marker of in-hospital mortality risk. Given the unadjusted results of our meta-analysis, future well-designed studies with multivariate analysis are warranted to confirm these findings.

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject?

Previous studies showed that COVID-19 patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease (CVD) were more likely to be admitted to intensive care unit, and in-hospital cardiac injury was commonly seen in critically ill patients. However, the relationship between CVD and cardiac injury with fatal outcomes has not been fully elucidated.

What might this study add?

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we found that in-hospital morality risk was significantly higher in COVID-19 patients with underlying CVD or hypertension, and patients with acute cardiac injury had a worse prognosis.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Among patients with COVID-19, those with established cardiovascular comorbidities and acute myocardial injury should be recognised earlier, and more aggressive treatment may be warranted. Elevated troponin may be considered as an important predictor for mortality risk.

heartjnl-2020-317062supp005.pdf (8.8KB, pdf)

Footnotes

XL and BG contributed equally.

Contributors: XL and BG performed the main research. TS and MC analysed the data. WL and KBW prepared the tables and figures. XL and XG wrote the main article. TG and ZZ critically reviewed and revised the article.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Song Z, Xu Y, Bao L, et al. From SARS to MERS, Thrusting coronaviruses into the spotlight. Viruses 2019;11:E59. 10.3390/v11010059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Xiong T-Y, Redwood S, Prendergast B, et al. Coronaviruses and the cardiovascular system: acute and long-term implications. Eur Heart J 2020:ehaa231. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Madjid M, Safavi-Naeini P, Solomon SD, et al. Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: a review. JAMA Cardiol 2020. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286. [Epub ahead of print: 27 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, et al. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031. [Epub ahead of print: 18 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mahase E. Coronavirus covid-19 has killed more people than SARS and MERS combined, despite lower case fatality rate. BMJ 2020;368:m641. 10.1136/bmj.m641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team [The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2020;41:145–51. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang J-J, Dong X, Cao Y-Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy 2020. 10.1111/all.14238. [Epub ahead of print: 19 Feb 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 2020;395:507–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis MLC, et al. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol 2004;203:631–7. 10.1002/path.1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020;395:497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhou B, She J, Wang Y, et al. The clinical characteristics of myocardial injury in severe and very severe patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease. J Infect 2020. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.021. [Epub ahead of print: 21 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-Analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (moose) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:603–5. 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ 2020;368:m1091 10.1136/bmj.m1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deng Y, Liu W, Liu K, et al. Clinical characteristics of fatal and recovered cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China: a retrospective study. Chin Med J 2020. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000824. [Epub ahead of print: 20 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guan W-jie, Liang W-hua, Zhao Y, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with Covid-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. European Respiratory Journal 2020;395:2000547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiology 2020. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. He XW, Lai JS, Cheng J, et al. [Impact of complicated myocardial injury on the clinical outcome of severe or critically ill COVID-19 patients]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi 2020;48:E011. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20200228-00137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol 2020. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [Epub ahead of print: 25 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yuan M, Yin W, Tao Z, et al. Association of radiologic findings with mortality of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. PLoS One 2020;15:e0230548. 10.1371/journal.pone.0230548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cao J, Tu W-J, Cheng W, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 102 patients with corona virus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa243. [Epub ahead of print: 02 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020;382:727–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cui J, Li F, Shi Z-L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 2019;17:181–92. 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [Epub ahead of print: 24 Feb 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li B, Yang J, Zhao F, et al. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol 2020;109:531–8. 10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in the novel Wuhan coronavirus (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Zuliani G, et al. Arterial hypertension and risk of death in patients with COVID-19 infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 2020. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.059. [Epub ahead of print: 11 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang C, Jin Z. An acute respiratory infection runs into the most common noncommunicable Epidemic-COVID-19 and cardiovascular diseases. JAMA Cardiol 2020. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0934. [Epub ahead of print: 25 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Corrales-Medina VF, Madjid M, Musher DM. Role of acute infection in triggering acute coronary syndromes. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10:83–92. 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70331-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zeng J, Huang J, Pan L. How to balance acute myocardial infarction and COVID-19: the protocols from Sichuan provincial people's Hospital. Intensive Care Med 2020. 10.1007/s00134-020-05993-9. [Epub ahead of print: 11 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Han Y, Zeng H, Jiang H, et al. Csc expert consensus on principles of clinical management of patients with severe emergent cardiovascular diseases during the COVID-19 epidemic. Circulation 2020. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047011. [Epub ahead of print: 27 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lippi G, Lavie CJ, Sanchis-Gomar F. Cardiac troponin I in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): evidence from a meta-analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2020. 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.03.001. [Epub ahead of print: 10 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:420–2. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, et al. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med 2020;368 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

heartjnl-2020-317062supp001.pdf (287KB, pdf)

heartjnl-2020-317062supp002.pdf (128.9KB, pdf)

heartjnl-2020-317062supp003.pdf (85.7KB, pdf)

heartjnl-2020-317062supp004.pdf (81.6KB, pdf)

heartjnl-2020-317062supp005.pdf (8.8KB, pdf)