Abstract

Background

Several treatments are available to reduce the risk of fragility fractures associated with osteoporosis. The choice of treatment requires knowledge of patients’ values and preferences. The aim of the present study was to summarize what is known about the values and preferences relevant to the management of osteoporosis in women.

Methods

We conducted a comprehensive search of several databases for studies reported in any language that had included women who had already started or were about to start any pharmacological therapy for osteoporosis. Pairs of reviewers independently selected the studies and extracted the data. The results were synthesized narratively.

Results

We included 26 studies reporting on 15,348 women (mean age, 66 years). The women considered the effectiveness and adverse events equally, followed by the convenience of taking the drug and its effect on daily routine (less frequent dosing was preferred, the oral route was preferred, and the injectable route was preferred over oral if given less frequently). The treatment cost and duration were less important factors for decision making. Fear of breast cancer and fear of resuming uterine bleeding were common reasons for not choosing estrogen therapy. Calcium and vitamin D were viewed as safe and natural. Across the studies, the preferences were not affected by age, previous drug exposure, or employment status.

Conclusions

Women starting osteoporosis medications value effectiveness and side effects equally and prefer medications given less frequently. Injectable drugs appear acceptable if given less frequently. More research on patient values and preferences is needed to guide decision making in osteoporosis.

Women starting osteoporosis medications value effectiveness and side effects equally and prefer less frequent dosing. Injectable drugs are acceptable if given less frequently.

Osteoporosis affects >200 million people worldwide (1). The disease is characterized by bone microarchitectural damage and skeletal fragility, which subsequently increases the risk of fractures (2, 3). Fractures can lead to a decreased quality of life, the development of comorbidities, death, and increased costs (4). The treatment of osteoporosis has been shown to reduce the risk of fractures (5). Many treatments are available with varying levels of effectiveness and safety and other characteristics that affect their use. Some of these characteristics, including cost, frequency, and route of administration, could affect patients’ adherence to the medication, which would thereby affect the effectiveness of the medication (6).

Because many treatments for osteoporosis have comparable effectiveness, it is these other characteristics and how the patient values them that will determine which of these therapies will be best for an individual patient. Therefore, consideration of the patient’s values and preferences could increase adherence to therapy and reduce the risk of fractures and adverse outcomes (7). To better understand the diversity and distribution of relevant values and preferences for antiosteoporosis medication and to inform the development of guidelines for the treatment of osteoporosis, we conducted the present systematic review.

Methods

Supplemental material for our report has been provided in an online repository (8). The protocol for the present systematic review was established a priori by members of a task force from the Endocrine Society charged with developing clinical practice guidelines on the management of primary osteoporosis in women.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria:

Included women who are postmenopausal with osteoporosis or osteopenia or those at risk of developing osteoporosis or osteopenia.

Examined women’s values and preferences while the women were taking or considering starting an antiosteoporosis drug.

The strategies for eliciting preferences could be open-ended questions or structured interviews, surveys, visual analog scales, standard gamble, time trade-off technique, decision aids, or presentation of hypothetical scenarios where participants were asked to make a treatment decision.

Any language of publication.

We excluded studies assessing health care professionals.

Search strategy

A medical reference librarian developed electronic search strategies. We searched Medline, Embase, Psychinfo, HealthStar, CINAHL, CENTRAL, and International Pharmaceuticals Abstracts from the dates of the inception of each database to February 2014. Finally, we reviewed the reference lists of all eligible studies.

Study selection

The reviewers worked in pairs and independently reviewed the references. Study selection and data extraction were conducted using DistillerSR systematic review software (Ottawa, ON, Canada). The potential eligibility of each of the abstracts and titles that resulted from the search strategy was reviewed in duplicate using a predefined abstract eligibility form detailing the selection criteria. Full-text versions of all potentially eligible studies were reviewed in duplicate for eligibility. Disagreements were resolved by consensus and, when this was not possible, by arbitration.

Data collection

Reviewers working in pairs extracted data using a predesigned standardized form, including study design, a full description of the participants enrolled, the number of participants, the response rate to the surveys, mean age, relevant values and preferences, and the measurement tools used in each study. Patient preferences could be related directly to a specific antiosteoporotic drug or to one drug compared with another.

Methodological quality and certainty in evidence

To assess the methodological quality of qualitative studies, we used the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklist (9, 10) and adapted the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Quality Assessment Tool for observational cohorts and cross-sectional studies to appraise surveys (11). To assess certainty in the whole body of evidence, we used the GRADE-CERQual tool, a tool derived from the GRADE approach that is used to evaluate the quality of evidence in qualitative research. The tool focuses on the methodological limitations of the studies (in our study, using CASP and NIH-NHLBI tools), coherence (consistency across studies and ability to explain data patterns), relevance (how direct are the results to the population of interest), and adequacy of data (the degree of richness and quantity of data to support the findings) (12).

Data synthesis

The data were inappropriate for a meta-analysis; therefore, the data were analyzed using a meta-narrative approach (13) focusing on the categorization of the themes identified across studies until saturation (all relevant themes were identified).

Results

Search results

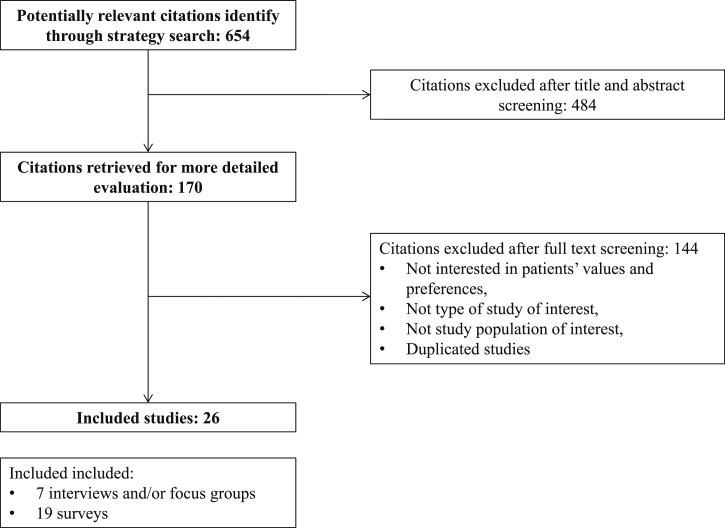

The process of selecting the studies is described in Fig. 1. We included 26 studies reporting the data from 15,348 women, with a mean age of 66 years. The available studies were cross-sectional, mostly surveys, followed by qualitative research studies using interviews and focus groups. Preference questionnaires were the most common tools used to elicit values, followed by hypothetical scenarios. The most common methods for eliciting a preference were questionnaires, the presentation of hypothetical scenarios for the decision of a treatment, probability trade-off techniques, and the forced ranking questionnaires. The osteoporosis treatments evaluated in the included studies were bisphosphonates, denosumab, teriparatide, calcitonin, and hormone replacement therapy.

Figure 1.

Study selection.

The treatment attributes found in the included studies for measuring the patient preferences were overall efficacy or effectiveness (absolute risk reduction of hip or vertebral fractures), dosing-related attributes (e.g., schedule or frequency, dosing procedures in relation to the time of the day and with or without food), route of administration, adverse events, treatment duration, cost, drug interactions, time on market, accordance of schedule into lifestyle, disposition to continue medication, willingness to take a long-term treatment, follow-up feasibility, and convenience. The included studies have been provided in the online repository (8).

Reported values and preferences

Effect of demographics

We found no evidence to suggest that preference was affected by age, previous exposure, or employment.

Dosage of the drug

The dosing schedule, frequency of medication, and/or overall dosage of the drug were assessed in 17 survey-based studies. Patients, in general, preferred a drug given less frequently, regardless of the route of administration. In only two surveys that assessed the effectiveness of less-frequent drug use in hypothetical scenarios, the more frequent and more effective drug was significantly preferred statistically (66.4% and 80.9% in the two studies). In 17 studies assessing the reason for choosing a specific dosing schedule, most women had a preference because it “fits better into their lifestyle” (7 studies) or was considered a “more convenient therapy” (11 studies).

Route of administration

Seven surveys assessed the preference of the route of administration for antiosteoporotic treatment. Five of these surveys compared an injectable versus an oral option. In four of these studies, patients preferred the injectable option (intravenous, subcutaneous, or intramuscular) over the oral option if given less frequently. An oral route was preferred in two studies over other routes of administration.

Effectiveness or efficacy of treatment

The effectiveness or efficacy of the drug was assessed in eight studies as a reduction in the risk of fracture (hip, spine, or other). In one study in which the therapy attributes were forced to be ranked, effectiveness, considered the ability to reduce the risk of fracture, was considered extremely important by 59% of the sample. In that same study, effectiveness was ranked first by 37% of the sample and by 48% of the osteoporosis-treated patients.

Adverse events

Adverse events were assessed in 13 surveys and were considered an important reason for having a preference for therapy. When bisphosphonates were used, adverse events were described as gastrointestinal discomfort or nausea and were the reason for favoring a less frequent dosing regimen. Only one study using hormone therapy replacement assessed the adverse events related to it, such as the risk of breast cancer and the resumption of any uterine bleeding. In that study, 60% of the patients who refused to take estrogen attributed their decision to their fear of an increased risk of breast cancer and 25% to a fear of resuming uterine bleeding. Calcium and vitamin D were viewed as safe and more natural than other antiosteoporosis medications.

Cost

The cost of the antiosteoporotic treatment was assessed in three studies. Two of these studies used the probability trade-off technique and ranking method to elicit their participants’ preferences. In one study, the participants ranked the cost as the third most important therapy attribute when considering a preference, after efficacy and adverse events. In another study, the out-of-pocket cost was considered “extremely important” by 33% of the participants.

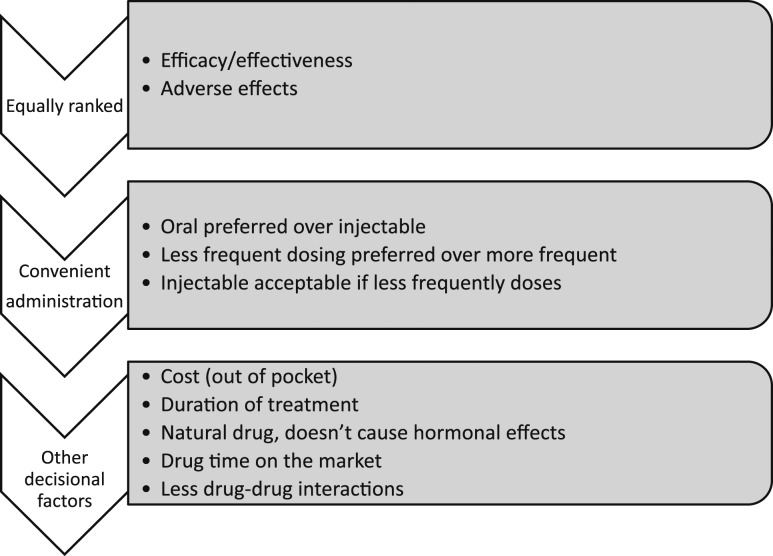

Other therapy attributes

Treatment duration was assessed in one study using a discrete-choice experiment and found that the optimum hypothetical total treatment duration was 5 years. Interactions with other drugs were assessed in two studies but were not considered of importance by most participants. The duration of the drug on the market was ranked as the least important attribute by 40% of the sample in one study. The dosing procedure (defined as what time of the day, with or without foods, and how long one would have to wait to eat after taking the drug) was ranked first by only 1% of the sample and was considered “extremely important” by 19%. The domains affecting decisions about choosing antiosteoporotic drugs are summarized in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Summary of values and preferences relevant to osteoporosis treatments.

Quality assessment and certainty of evidence

Overall, most of the interviews and focus group studies had good methodological quality. They used approaches consistent with the objectives of the studies, with adequate data collection and analysis, and stated the findings clearly. Ethical issues were explicitly addressed in only two of the seven qualitative research studies included in the present review. For the surveys, the response rate was, overall, excellent (15 of 19 had a response rate >80%) The response rate ranged from 29.7% to 100%. A detailed description of the quality assessment using the NIH-NHLBI Quality Assessment Tool has been provided in the online repository (8).

Overall, the available evidence warrants moderate certainty considering the GRADE-CERQual domains. In terms of study limitations and using the CASP and NHLBI-NIH tools, we found no major concerns, as described. In terms of relevance, the studies had enrolled the appropriate population (women contemplating decisions regarding osteoporosis drugs) and discussed drugs currently used in practice (perhaps less likely for calcitonin). For the domain of adequacy, the number of studies and participants was more than sufficient to support the conclusions of the present review. For the domain of coherence, the studies were consistent in their findings, and the results were intuitive to a great extent.

Discussion

Main findings

We conducted a systematic review of studies that had evaluated women’s values and preferences relevant to the decision of taking antiosteoporotic drugs. We found several relevant domains. Women, in general, seemed to consider effectiveness and adverse events equally. Next, were the convenience of taking the drug and its effect on their daily routine (less frequent dosing was preferred, oral administration was preferred, and injectable was preferred over oral if given less frequently). The cost and duration of treatment were less important factors. It did not appear that patient demographic data affected these preferences.

Study limitations and strengths

Most of the studies did not report measures of participants’ comprehension of the questions being formulated or the method used to elicit a preference, such as trade-off or hypothetical scenarios. Studies that included patients with osteoporosis or a history of antiosteoporotic treatment and patients at risk of developing osteoporosis and not taking any medication did not always present the results separately. Although gastrointestinal adverse events were the most commonly observed with the use of bisphosphonates, in most studies, the adverse event mentioned to the patients was nausea. The trade-off and hypothetical scenarios were created using only this adverse event and not other more serious events such as esophageal ulcer, esophagitis, or reflux (14).

In terms of the strengths of the present study, we followed an a priori protocol developed by experts from the Endocrine Society and conducted a comprehensive literature search and removed duplicate studies. To the best of our knowledge, the present review is the first systematic review addressing women’s values and preferences conducted to support formulation of a guideline. The included studies had a very good response rate and had adequate methodology. Overall, the available evidence warrants moderate certainty considering the GRADE-CERQual domains of the study limitations, relevance, adequacy, and coherence.

Clinical implications

Modern guideline development has underscored the importance of incorporating values and preferences in decision making and developing recommendations. This is demonstrated in the GRADE approach and described in the Institute of Medicine (the National Academy of Medicine) report on trustworthy guidelines (15, 16). Guideline efforts have started to include a systematic review of patient values and preferences (17). It is important to always attempt to evaluate the distribution and attributes of the values and preferences of patients because such values could differ from those of physicians (18). de Bekker-Grob et al. (19) found that general practitioners gave significantly higher values on the effectiveness of the drug and short total duration of preventive treatment compared with patients. From a guideline developer’s viewpoint, encountering unclear evidence regarding the values and preferences or evidence, suggesting that such values differ widely across patients, implies that a weak (or conditional) recommendation would be more reasonable. Clear and consistent values would provide a rationale for a strong recommendation that would apply to most patients with minimal variance.

Conclusions

Women facing the decision of taking medications for osteoporosis appear to value effectiveness and side effects equally and to prefer medications given less frequently. Injectable drugs appear to be acceptable as long as they are given less frequently. More research on patient values and preferences is needed to guide decision making in treatments for osteoporosis. The current evidence focused on the convenience of dosing regimens and would be insufficient to guide trade-offs or comparisons between drugs.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The present review was partially funded by a contract from the Endocrine Society. M.R.G. was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (Clinical Translational Science Awards grant TL1 TR000137). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Endocrine Society or National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CASP

Critical Appraisal Skills Program

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- NHLBI

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

References

- 1. Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ III. Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporosis Int.1992;2(6):285–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sornay-Rendu E, Boutroy S, Munoz F, Delmas PD. Alterations of cortical and trabecular architecture are associated with fractures in postmenopausal women, partially independent of decreased BMD measured by DXA: the OFELY study. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(3):425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY; Scientific Advisory Board of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) and the Committee of Scientific Advisors of the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) . European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(1):23–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lindsay R. The burden of osteoporosis: cost. Am J Med. 1995;98(2A)9S–11S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murad MH, Drake MT, Mullan RJ, Mauck KF, Stuart LM, Lane MA, Abu Elnour NO, Erwin PJ, Hazem A, Puhan MA, Li T, Montori VM. Clinical review: comparative effectiveness of drug treatments to prevent fragility fractures: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(6):1871–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. The Adherence Gap: Why Osteoporosis Patients Don’t Continue With Treatment. Nyon, Switzerland:International Osteoporosis Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Montori VM, Shah ND, Pencille LJ, Branda ME, Van Houten HK, Swiglo BA, Kesman RL, Tulledge-Scheitel SM, Jaeger TM, Johnson RE, Bartel GA, Melton LJ III, Wermers RA. Use of a decision aid to improve treatment decisions in osteoporosis: the osteoporosis choice randomized trial. Am J Med. 2011;124(6):549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrionuevo P, Gionfriddo MR, Castaneda-Guarderas, Zeballos-Palacios C, Bora P, Mohammed K, Benkhadra K, Sarigianni M, Murad MH. Data from: Women’s values and preferences regarding osteoporosis treatments: a systematic review. figshare 2019. Accessed 13 February 2019. https://figshare.com/articles/Appendix_osteoporosis_values_and_preferences/7629425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. Critical Appraisal Skills Program. 10 Questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. Qualitative Research checklist 31.05.13. Available at: http://www.casp-uk.net. Accessed 13 February 2019..

- 10. Chenail RJ. Learning to appraise the quality of qualitative research articles: a contextualized learning object for constructing knowledge. Qual Rep. 2011;16(1):236–248. [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed 13 February 2019..

- 12. Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Carlsen B, Colvin CJ, Gülmezoglu M, Noyes J, Booth A, Garside R, Rashidian A. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Greenhalgh T, Wong G, Westhorp G, Pawson R. Protocol—realist and meta-narrative evidence synthesis: evolving standards (RAMESES). BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taggart H, Bolognese MA, Lindsay R, Ettinger MP, Mulder H, Josse RG, Roberts A, Zippel H, Adami S, Ernst TF, Stevens KP. Upper gastrointestinal tract safety of risedronate: a pooled analysis of 9 clinical trials. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77(3):262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Pottie K, Meerpohl JJ, Coello PA, Rind D, Montori VM, Brito JP, Norris S, Elbarbary M, Post P, Nasser M, Shukla V, Jaeschke R, Brozek J, Djulbegovic B, Guyatt G. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation-determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):726–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: National Academic Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17. MacLean S, Mulla S, Akl EA, Jankowski M, Vandvik PO, Ebrahim S, McLeod S, Bhatnagar N, Guyatt GH. ; American College of Chest Physicians. Patient values and preferences in decision making for antithrombotic therapy: a systematic review: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012. ;141(2 Suppl):e1S–e23S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Devereaux PJ, Anderson DR, Gardner MJ, Putnam W, Flowerdew GJ, Brownell BF, Nagpal S, Cox JL. Differences between perspectives of physicians and patients on anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation: observational study. BMJ. 2001;323(7323):1218–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Bekker-Grob EW, Essink-Bot ML, Meerding WJ, Koes BW, Steyerberg EW. Preferences of GPs and patients for preventive osteoporosis drug treatment: a discrete-choice experiment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(3):211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]