Abstract

We aimed to characterize the epidemiology, diagnostic peculiarities and outcome determinants of bacterial myocarditis.

Two cases from our institution and literature reports were collected ending up with a total of 66 cases. In 37 (56%) patients, the diagnosis was confirmed by magnetic resonance and histopathological criteria. The other patients were classified as having possible myocarditis.

Only occurrence of rhythm disturbances was associated with the specific diagnosis of myocarditis (p = 0.04). Thirty-two (48%) patients presented with severe sepsis that was associated with a worse prognosis. At multivariate analysis, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at admission and heart rhythm disturbances were associated with incomplete recovery (odds ratio (OR) 1.1, 95% (CI) 1.03–1.2, p = 0.004 and OR 6.6, 95% CI 1.35–32.5, p = 0.02, respectively).

In summary, bacterial myocarditis is uncommon. Most commonly, it is secondary to septic dissemination of bacteria or to transient secondary myocardial toxicity.

Keywords: Myocarditis, Bacterial, Sepsis, Diagnosis, Epidemiology

1. Introduction

Myocarditis is an inflammatory disease of the myocardium diagnosed by established histological, immunological and immunohistochemical criteria. The most frequent cause of myocarditis, especially in Europe and North America, is viral infections such as enterovirus, adenovirus, influenza virus, human herpes virus and parvovirus.1 However, cases of bacterial myocarditis can also be found in clinical practice and reported in the literature. Bacterial etiology is uncommon, and the clinical presentation and course can overlap with aspecific left ventricular dysfunction secondary to sepsis.

In western countries, the most common bacterial causes of myocarditis are Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus spp. infection, although myocardial infections associated with a broad range of bacterial pathogens have been described.2 However, the actual etiology often remains undetermined because of the limited access to endomyocardial biopsy in clinical practice.

The primary objective of this study was to review the epidemiology of this uncommon condition, with a particular focus on the different bacterial species involved in myocardial injury and the respective typical clinical presentation. Overwhelming sepsis is usually associated with myocardial depression and heart failure, eventually leading to secondary cardiogenic shock, without specific diagnostic criteria suggesting the diagnosis of myocarditis. The secondary objective was to explore clinical phenotype differences among patients with suspected or proved myocarditis, presenting with or without severe sepsis and/or septic shock. We have included in the series two cases of acute bacterial myocarditis from our institution secondary to Streptococcus pyogenes and Escherichia coli infection, respectively.

2. Case description

2.1. Case A

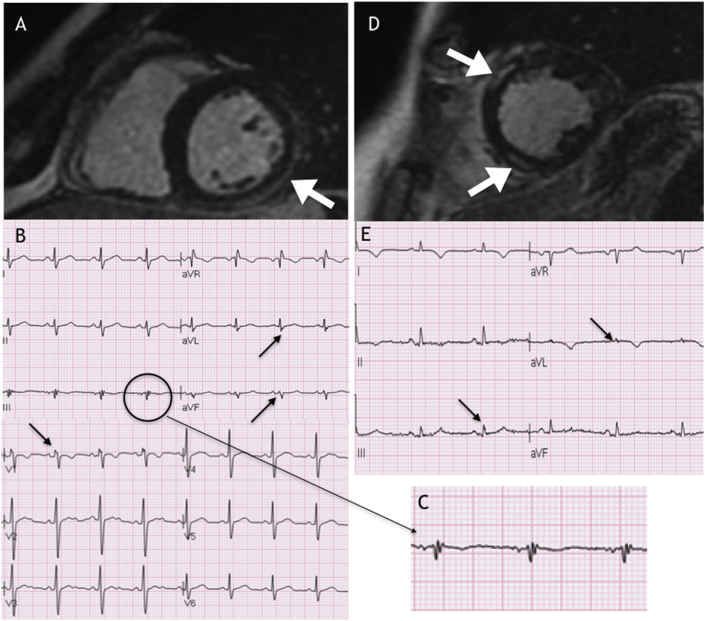

A previously healthy 35-year-old male, with a 2-day history of fever (39 °C) after an accidental left knee trauma with swelling, presented to the emergency department due to severe chest pain and dizzy spells. His blood pressure was 80/50 mmHg, and his heart rate was 108 bpm. The echocardiography showed severe left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF 10–15%), and the first ECG revealed sinus tachycardia and infero-lateral ST-elevation. He was admitted to the cardiac intensive care unit due to progressive hemodynamic deterioration and lactic acidosis, requiring inotropic support with adrenaline uptitrated to 0.1 mcg/kg/min, fluid resuscitation and intravenous antibiotics (Ampicillin/Sulbactam). Peak C reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin and troponin I levels were 38 mg/L (normal <1), 60 ng/mL (normal <0.05) and 49 ng/mL (normal <0.07 ng/mL), respectively. On the second day, the LVEF improved to 45%. After 4 days, left knee arthrocentesis was performed, and cultures were positive for S. Pyogenes. QRS fragmentation in DIII, aVf, aVL and V1 (Fig. 1A and C) appeared after 48 h, which was consistent with late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) on cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging involving the inferior/lateral area of the left ventricle (Fig. 1A). The patient clinical status progressively improved, and he was discharged on day 16. Treatment with low-dose angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I) was started. No beta-blockers were administered due to a tendency toward sinus bradycardia. At the 3-months follow-up, left ventricular function had normalized. CMR imaging after 12 months showed almost complete resolution of LGE.

Fig. 1.

Panel A: First case, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showing late gadolinium enhancement. Panels B and C: ECG showing QRS fragmentation. Panel D: Second case, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showing late gadolinium enhancement. Panel E: ECG showing QRS fragmentation.

2.2. Case B

A previously healthy 51-year-old female, admitted due to a right ureteral stone with hydronephrosis, underwent uretheropielography and stone removal. After a few hours, she developed a temperature up to 40 °C, hypotension (80/50 mmHg) and tachycardia (120 bpm), consistent with severe sepsis. Echocardiography revealed a LVEF of 40% with antero-septal hypokinesis, and the ECG showed anterolateral ST-elevation. The patient was admitted to the cardiac intensive care unit and intubated; her clinical conditions improved after fluid administration and noradrenaline infusion. Her TnI peak was 113 ng/mL (normal < 0.07 ng/mL), CRP was 30 mg/dl (normal < 1), and white blood count was 18,000/mm3. Blood cultures were positive for E. coli, and treatment with intravenous Cefotaxime was started. After 2 days, her clinical status improved and she was extubated. Coronary angiography excluded significant pathology. CMR imaging (Day 5) revealed LGE enhancement involving the antero-septal and inferior regions of the left ventricle, that roughly correlated with ECG fragmentation in DIII and aVL (Fig. 1D and E). The patient was discharged on day 21 and instructed to take an ACE-I, beta-blocker and spironolactone. CMR performed 6 months later showed a partial reduction of the LGE areas and left ventricular function improvement (LVEF 45%). The ECG at the 6-months follow-up was not normalized, with persistence of QRS fragmentation and T inversion in the antero-lateral leads.

3. Materials and methods

We performed a systematic literature search for all reported cases of bacterial myocarditis from 2000 to 2018. A literature search in PubMed using “Bacterial” and “myocarditis” as keywords, limiting the results to humans and studies in the English language, was conducted.

Papers fulfilling the following criteria were included1: case report or case series2; inclusion of patients with at least one positive blood, stool and/or tissue culture3; availability of information about ECG, serum cardiac markers (troponin) and ventricular function. The following variables were retrieved from each paper: bacterial etiology, gender, age, clinical presentation (fever with or without rush, respiratory or gastrointestinal syndrome and chest pain), CRP peak, troponin peak, ECG presentation, arrhythmias, presence of QRS fragmentation, LVEF at admission, presence of LGE, presence of diagnostic criteria at the biopsy. We labelled as tachycardia any fast ventricular rhythm and bradycardia any heart rate lower than 60 bpm secondary to high degree AV block. The most significant and prognostically relevant heart rhythm disorder was considered in each case.

The whole population was dichotomized according to the presence or absence of septic shock and/or severe sepsis to investigate the association of this particular clinical presentation with the other variables. We assumed that, in the papers, the current definition of sepsis and septic shock was accepted, whenever not clearly stated. For analysis purposes severe sepsis and septic shock were considered as a single group gathering together patients with evidence of infection associated with organ dysfunction and circulatory failure.

Patients were categorized into three groups according to the diagnostic criteria of myocarditis: possible myocarditis, in the presence of LVEF depression in the context of systemic bacterial infection but without specific evidence of inflammatory myocardial involvement, probable myocarditis, in the presence of suggestive CMR findings, and definite myocarditis, according to histopathological criteria.

Patients with definite or probable myocarditis were grouped together and compared with those with the absence of specific diagnostic criteria (i.e. possible myocarditis).

For the analysis of outcomes, we considered overall mortality and complete recovery rate, defined as normalization of echocardiographic or CMR LVEF and/or resolution of LGE. All other patients with abnormal ventricular function of any degree were included in the group classified as having partial recovery.

3.1. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as medians and interquartile ranges and were compared by the Wilcoxon rank sum test (Mann–Whitney test). Comparisons between more than two groups were performed by the Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical variables are reported as counts and percentages and were compared using the chi square test and Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Multivariate association with categorical variables was determined by logistic regression analysis. A p value of 0.05 was assumed to indicate statistical significance.

4. Results

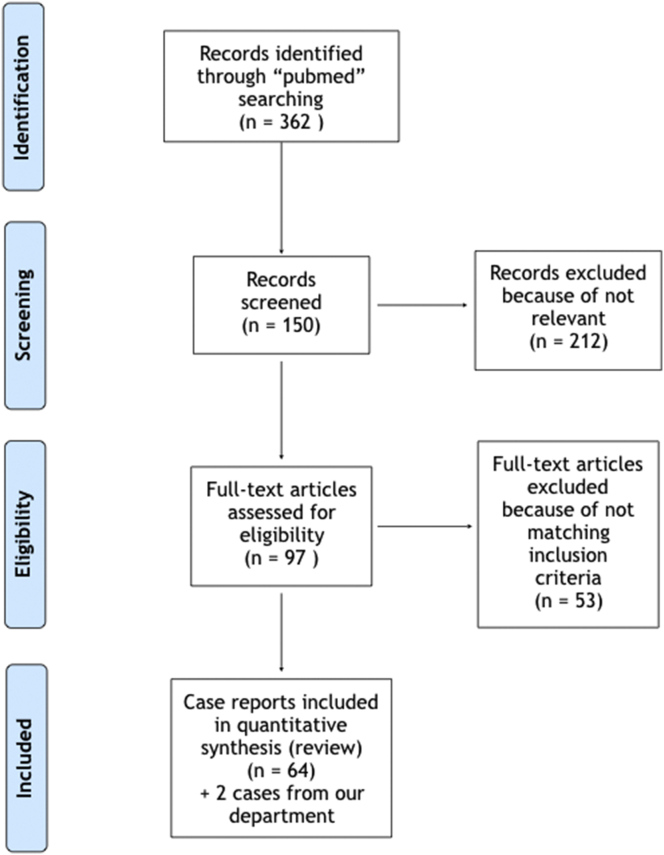

The search yielded 362 publications. A total of 59 papers and 64 case reports were deemed eligible for study inclusion, with a total of 66 patients (including ours), thirty-two of whom had a clinical course characterized by sepsis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Flowchart summarizing the screening and inclusion of relevant papers.

Table 1, Table 2 summarize the demographic, clinical, bacterial etiology and diagnostic examination data for individuals in the publications presenting with or without severe sepsis, respectively.

Table 1.

Overview of epidemiology and clinical characteristics of patients with bacterial myocarditis presenting with severe sepsis.

| Author | Ref | Year | Bacterial | Gender | Age (years) | Clinical presentation | Chest pain | CRP peak (mg/L) | STN Troponin ratio | ECG | Arrhythmias | fQRS | CMRI LGE | EF at admission (%) | EMB/Autopsy | ICU | Complete recovery | Partial recovery | Death | Associated conditions | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | – | 2019 | Streptococcus pyogenes | M | 34 | Fever | + | 38 | 700 | ST-elevation | 0 | + | + | 15 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | Septic arthritis | Probable |

| Case 2 | – | 2019 | Escherichia coli | F | 51 | Fever | + | 30 | 1614 | ST-elevation | 0 | + | + | 30 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | Urinary tract infection | Probable |

| Sikary et al. | 4 | 2016 | Streptococcus pyogenes | F | 7 | Fever, Resp | 0 | – | – | – | VT | – | – | – | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | – | Definite |

| Ozkaya et al. | 5 | 2005 | Streptococcus pyogenes | F | 35 | Fever, Resp, Rash | + | – | – | – | VT | – | – | – | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | – | Definite |

| Dominguez et al. | 6 | 2013 | Streptococcus B-hemolytic | M | 46 | Fever, Rash | 0 | – | 550 | ST-elevation | AV block | – | + | 60 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | Erysipelas | Probable |

| Lee et al. | 7 | 2008 | MRSA | M | 41 | Fever, Resp | + | – | 8 | ST-elevation | 0 | + | – | 20 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | Pneumonia | Possible |

| Khan et al. | 8 | 2007 | MRSA | M | 41 | Fever | + | – | – | ST-elevation, BBSx | AV block | – | – | 45 | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | AV Fistula Infection | Definite |

| Elias et al. | 9 | 2008 | MSSA | M | 45 | Fever | + | 160 | – | ST-elevation | VT | + | – | 20 | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | – | Definite |

| Buoneb et al. | 10 | 2018 | Neisseria meningitidis | M | 16 | Fever, Rash | + | – | 1071 | ST-elevation | 0 | – | + | 35 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable |

| Gawalkar et al. | 11 | 2017 | Neisseria meningitidis | M | 17 | Fever, Resp, Rash | 0 | – | – | Ripolarization abn. | 0 | – | – | 30 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | Purpura fulminant | Possible |

| Al Shamkhani et al. | 12 | 2015 | Salmonella enteritidis | M | 28 | Fever, GE | + | 287 | 225 | ST-elevation | 0 | + | – | 55 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | Rabdomyolysis | Possible |

| Childs et al. | 13 | 2012 | Salmonella enteritidis | F | 16 | Fever, GE | 0 | 206 | 1071 | Ripolarization abn. | 0 | 0 | – | 47 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | – | Possible |

| Villablanca et al. | 14 | 2015 | Salmonella berta | M | 19 | Fever, GE | + | – | 556 | ST-elevation | 0 | + | + | 40 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable |

| Al-aqeedi et al. | 15 | 2009 | Salmonella typhi | M | 34 | Fever, GE | + | – | 98 | Ripolarization abn. | 0 | + | – | 23 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | Rabdomyolysis | Possible |

| Türoff et al. | 16 | 2008 | Salmonella typhi | F | 42 | Fever, GE, Rash | + | 39.27 | – | Ripolarization abn. | VT | – | – | 40 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | – | Possible |

| Komuro et al. | 17 | 2018 | Escherichia coli | F | 69 | Fever | + | 8 | – | ST-elevation, BBSx | AV block | 0 | – | 31 | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | Coronaropathy | Definite |

| Gentile et al. | 18 | 2010 | Escherichia coli | M | 65 | Fever | + | – | 170 | ST-elevation | 0 | + | – | 58 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | Urinary tract infection | Possible |

| Chen et al. | 19 | 2010 | Escherichia coli | F | 25 | Fever, GE | + | – | 882 | ST-elevation | 0 | 0 | – | 50 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | Urinary tract infection | Possible |

| De Cock et al. | 20 | 2012 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 42 | Fever, GE | + | – | 116 | ST-elevation | 0 | – | + | 40 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable |

| Pena et al. | 21 | 2006 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 16 | Fever, GE | + | – | 398 | ST-elevation | 0 | – | – | – | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | Aeromomas hydrophila | Definite |

| Kushawaha et al. | 22 | 2013 | Rickettsia rickettsii | M | 26 | Fever, Rash | + | – | 3 | Normal | 0 | + | – | 20 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | – | Possible |

| Wilson et al. | 23 | 2012 | Rickettsia australis | F | 52 | Fever, Rash | + | – | 990 | ST-elevation | 0 | – | – | 20 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | – | Possible |

| Roch et al. | 24 | 2008 | Rickettsia africae | F | 74 | Fever, Rash | + | – | – | ST-elevation | 0 | – | – | 35 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | – | Possible |

| Zou et al. | 25 | 2016 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | M | 66 | Fever | + | – | 67 | ST-elevation | 0 | + | – | 45 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | Liver abscess | Possible |

| Chuang et al. | 26 | 2012 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | M | 52 | Fever, Resp | + | – | 3 | Idioventricular rhythm | VT | – | – | 50 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | – | Probable |

| Ladani et al. | 27 | 2015 | Listeria monocytogenes | M | 47 | Fever, Resp | + | – | 24 | ST-elevation | VT | + | + | 35 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | ICD implantation | Probable |

| Haddad et al. | 28 | 2007 | Listeria monocytogenes | F | 49 | Fever | + | – | 53 | – | 0 | – | – | 12 | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | – | Definite |

| Pushpakumara et al. | 29 | 2015 | Leptospira spp | M | 36 | Fever | + | 74 | 228 | ST-elevation | VT | 0 | – | 20 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | Respiratory distress | Possible |

| Morgan et al | 30 | 2017 | Chlamydia trachomatis | F | 19 | Fever | 0 | – | – | Ripolarization abn. | 0 | – | – | 35 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | PID | Possible |

| Hoefer et al. | 31 | 2005 | Chlamydia pneumoniae | F | 24 | Fever, Resp | 0 | 5 | – | – | VT | – | – | 10 | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | BVAD | Definite |

| Suesaowalak et al. | 32 | 2008 | Chlamydia pneumoniae | M | 11 | Fever, Resp, GE, Rash | + | 17 | 32 | Ripolarization abn. | 0 | – | – | 50 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | – | Possible |

| Efe et al. | 33 | 2009 | Brucella spp | F | 51 | Resp | + | 55 | 140 | Ripolarization abn. | 0 | – | – | 15 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | Ascites | Possible |

Table 2.

Overview of epidemiology and clinical characteristics of patients with bacterial myocarditis not presenting with severe sepsis.

| Author | Ref. | Year | Bacterial | Gender | Age (years) | Clinical presentation | Chest pain | CRP peak (mg/L) | STN Troponin ratio | ECG | Arrhythmias | fQRS | CMRI LGE | EF at admission (%) | EMB/Autopsy | ICU | Complete recovery | Partial recovery | Death | Associated conditions | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Royston et al. | 34 | 2018 | Streptococcus sanguinis | M | 39 | GE | + | – | 580 | ST-elevation | 0 | – | + | – | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | Endocarditis | Probable |

| Aguirre et al. | 35 | 2015 | Streptococcus A | M | 42 | Fever, Resp | + | – | 686 | ST-elevation | 0 | + | + | 55 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable |

| Sundbom et al. | 36 | 2018 | Salmonella enteritidis | M | 22 | Fever, GE | + | 200 | 209 | ST-elevation | 0 | + | + | 46 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable |

| Hibbert et al. | 37 | 2010 | Salmonella enteritidis | M | 25 | Fever, GE | + | – | 26 | ST-elevation | VF | 0 | + | 55 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | Probable |

| Palombo et al. | 38 | 2013 | Salmonella typhi | M | 27 | Fever, GE | + | – | 1.3 | ST-elevation | VF | – | + | 30 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | ICD implantation | Probable |

| Williams et al. | 39 | 2004 | Salmonella typhi | M | 31 | GE | + | 72 | 77 | ST-elevation | 0 | + | – | 45 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Possible |

| Uribarri et al. | 40 | 2011 | Escherichia coli | M | 64 | Fever, GE | + | – | 3 | Normal | 0 | – | + | 50 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | Urinary tract infection | Probable |

| Inayat et al. | 41 | 2017 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 20 | Fever, GE | + | 121 | 1300 | Ripolarization abn. | 0 | + | + | 41 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable |

| Hessulf et al. | 42 | 2016 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 24 | GE | + | 89.1 | 72 | ST-elevation | 0 | + | – | 60 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Possible |

| 2016 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 23 | Fever, GE | + | 46.5 | 18 | Normal | 0 | + | – | 60 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Possible | ||

| Panikkath et al. | 43 | 2014 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 43 | Fever, GE | + | 90.7 | 48 | ST-elevation | 0 | + | + | 65 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable |

| De Cock et al. | 20 | 2012 | Campylobacter spp | M | 21 | Fever, GE | + | – | 120 | Normal | 0 | – | + | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | – | Probable |

| 2012 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 24 | Fever, GE | + | – | 89 | ST-elevation | 0 | – | + | 40 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable | ||

| Fica et al. | 44 | 2012 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 17 | Fever, GE | + | 269 | 413 | ST-elevation | 0 | – | + | 60 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable |

| Kratzer et al. | 45 | 2010 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 19 | Fever, GE | + | 15.05 | 7 | ST-elevation | 0 | + | + | 55 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable |

| Nevzorov et al. | 46 | 2010 | Campylobacter spp | M | 24 | Fever, GE | 0 | – | – | Ripolarization abn. | NSVT | + | – | 45 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Possible |

| Heinzl et al. | 47 | 2009 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 16 | Fever, GE | + | 132 | 17 | ST-elevation | 0 | – | + | 45 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable |

| 2009 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 17 | Fever, GE | + | 32 | 8 | ST-elevation | 0 | – | + | 60 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable | ||

| Turley et al. | 48 | 2008 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 24 | Fever, GE | + | 125 | 140 | ST-elevation | 0 | 0 | + | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | Noonan Syndrome | Probable |

| Kotilainen et al. | 49 | 2006 | Campylobacter spp | M | 47 | Fever, GE | + | 73 | – | Ripolarization abn. | 0 | – | – | 50 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | Acute appendicitis | Possible |

| Williams et al. | 39 | 2004 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 40 | GE | + | 48 | 15 | Normal | 0 | – | – | 60 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Possible |

| Cunningham et al. | 50 | 2003 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 30 | Fever, GE | + | – | 604 | Ripolarization abn. | 0 | – | – | 60 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Possible |

| Hannu et al. | 51 | 2002 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 43 | GE | + | 54 | – | ST-elevation | 0 | – | – | 45 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Possible |

| 2002 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 30 | Fever, GE | + | 30 | – | ST-elevation | 0 | – | – | 50 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Possible | ||

| Cox et al. | 52 | 2001 | Campylobacter jejuni | M | 32 | Fever, GE | + | 123 | – | Ripolarization abn. | 0 | – | + | 40 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable |

| Revilla-Marti et al. | 53 | 2017 | Rickettsia sibirica m. | M | 39 | Fever, Rash | + | – | 41 | ST-elevation | 0 | – | + | 55 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable |

| Silva et al. | 54 | 2015 | Rickettsia slovaca | M | 28 | Rash | + | – | 30 | ST-elevation | 0 | – | + | 55 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Probable |

| Doyle et al. | 55 | 2006 | Rickettsia rickettsii | M | 54 | Fever, Rash | + | – | 16 | Normal | 0 | – | – | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | – | Possible |

| Bellini et al. | 56 | 2005 | Rickettsia africae | M | 35 | Fever, Rash | + | – | 91 | Ripolarization abn. | 0 | + | – | 60 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Possible |

| Silingardi et al. | 57 | 2006 | Mycobacterium avium | F | 33 | – | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | – | Definite |

| Dellegrottaglie et al. | 58 | 2014 | Chlamydia trachomatis | M | 32 | – | + | – | 1600 | ST-elevation | 0 | + | + | 55 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | Epididymitis | Probable |

| Mavrogeni et al. | 59 | 2008 | Chlamydia trachomatis | M | 49 | Fever | + | – | 23 | – | 0 | – | + | 47 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | Prostatitis | Possible |

| Carrascosa et al. | 60 | 2012 | Coxiella burnetii | M | 23 | Fever | + | – | 655 | ST-elevation | NSVT | – | + | 55 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | Pneumonia and hepatitis | Probable |

| Paz et al. | 61 | 2002 | Mycoplasma pneumoniae | F | 30 | Fever, Resp | + | – | – | ST-elevation | 0 | – | – | 50 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | – | Possible |

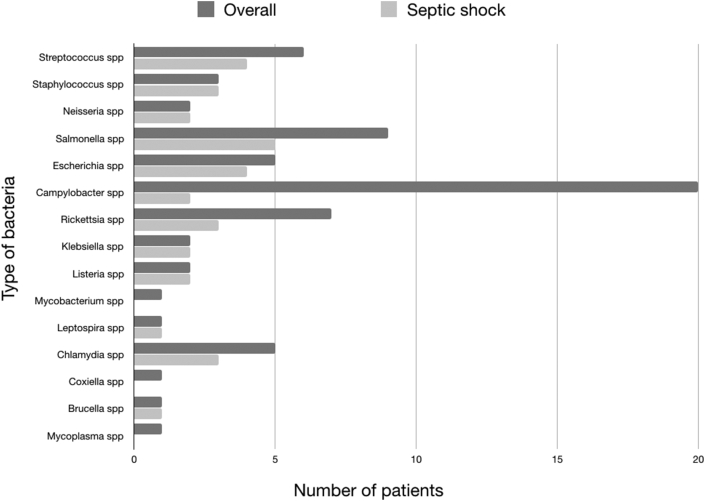

Fifteen different etiologies were recorded. Staphylococcus, Neisseria, Klesiella, Listeria, Leptospira and Brucella species were more commonly found in patients presenting with severe sepsis. Blood culture were positive in 14 out of 32 (44%) and in 4 out of 34 (12%) patients presenting with or without severe sepsis respectively (Fig. 3; Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Relative prevalence of bacteria and culture results.

Table 3.

Prevalence of bacterial etiologies and culture positivity.

| Bacterial species | Overall, n 66 | Severe sepsis, n 32 | Blood cultures | Tissue cultures | Biological samples cultures | Not severe sepsis, n 34 | Blood cultures | Tissue cultures | Biological samples cultures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Streptococcus spp, n (%) | 6 (9) | 4 (12) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 2 (6) | 1 (50) | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Staphylococcus spp, n (%) | 3 (4.5) | 3 (9) | 3 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| 3 | Neisseria spp, n (%) | 2 (3) | 2 (6) | 2 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| 4 | Salmonella spp, n (%) | 9 (13.6) | 5 (16) | 3 (60) | 0 | 2 (40) | 4 (12) | 2 (50) | 0 | 2 (50) |

| 5 | Escherichia spp, n (%) | 5 (7.6) | 4 (12) | 4 (100) | 0 | 1 (25) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) |

| 6 | Campylobacter spp, n (%) | 20 (30) | 2 (6) | 0 | 0 | 2 (100) | 18 (53) | 0 | 0 | 18 (100) |

| 7 | Rickettsia spp, n (%) | 7 (10.6) | 3 (9) | 0 | 1 (33) | 0 | 4 (12) | 0 | 1 (25) | 0 |

| 8 | Klebsiella spp, n (%) | 2 (3) | 2 (6) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| 9 | Listeria spp, n (%) | 2 (3) | 2 (6) | 2 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| 10 | Mycobacterium spp, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 |

| 11 | Leptospira spp, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| 12 | Chlamydia spp, n (%) | 5 (7.6) | 3 (9) | 0 | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 2 (6) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

| 13 | Coxiella spp, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | Brucella spp, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3) | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| 15 | Mycoplasma spp, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

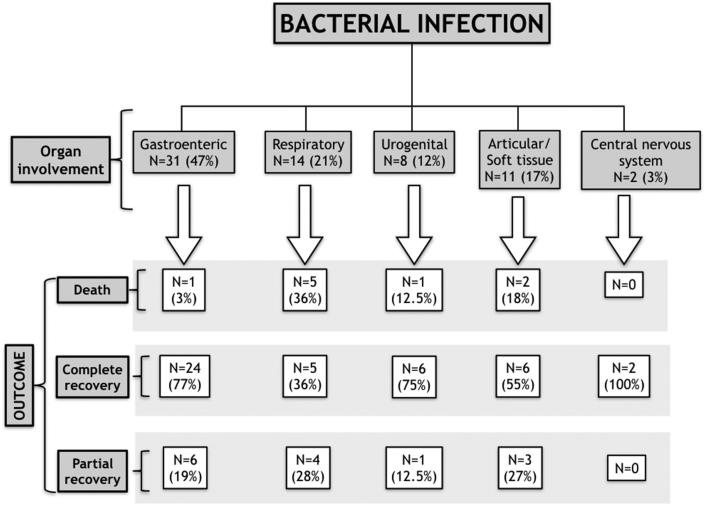

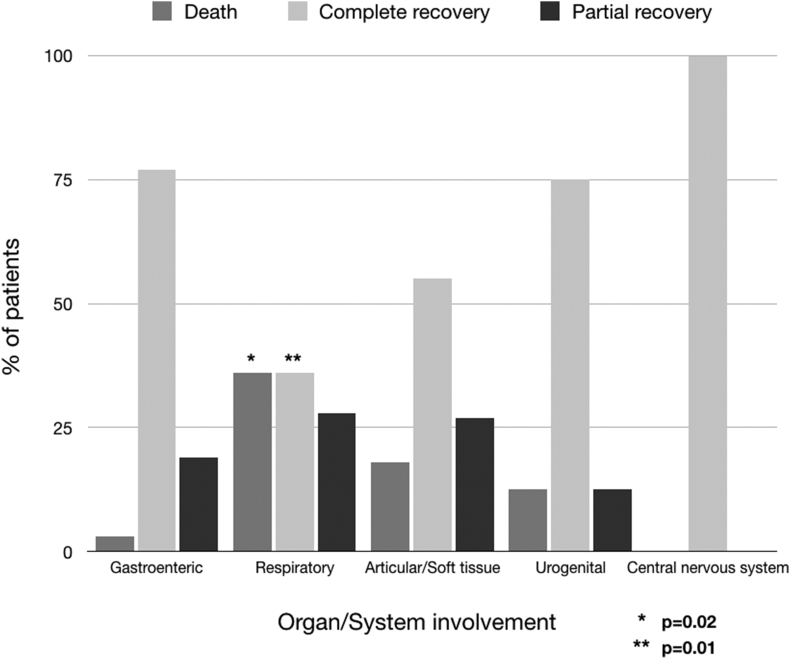

Table 4 presents general demographic, clinical, instrumental and laboratory data as well as differences between patients with and without sepsis. Males were more prevalent in the whole group, accounting for 51 patients (77%), while females more frequently presented with sepsis (13 out of 32 (41%) vs 2 out of 34 (6%); p = 0.001). Chest pain and fever were the most common clinical presentations, followed by gastrointestinal syndrome, skin rash and respiratory symptoms, with frequencies of 58 (88%), 57 (86%), 33 (50%), 13 (20%), and 11 (17%), respectively. Fever and respiratory symptoms were more frequently found in patients who developed severe sepsis (31 out of 32 (97%) vs 26 out of 34 (76)%, p = 0.02, and 9 out of 32 (28%) vs 2 out of 34 (6%), p = 0.02, respectively). Symptoms at presentation correlated well with the involved organs, and are grouped as follows: gastrointestinal, 31 (47%); respiratory, 14 (21%); urogenital, 8 (12%); articular/soft tissue, 11 (17%), and central nervous system, 2 (3%) (Fig. 4).

Table 4.

Demographic clinical and instrumental characteristic.

| Overall, n 66 | Severe sepsis, n 32 | Not severe sepsis, n 34 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (25th-75th) | 32 (23–43) | 38.5 (21.5–50) | 30 (23–39) | 0.1 |

| Males, n (%) | 51 (77) | 19 (59) | 32 (94) | 0.001 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Possible, n (%) | 29 (44) | 16 (50) | 13 (38) | |

| Probable, n (%) | 28 (42) | 8 (25) | 20 (59) | |

| Definite, n (%) | 9 (14) | 8 (25) | 1 (3) | 0.008 |

| Clinical presentation | ||||

| Fever, n (%) | 57 (86) | 31 (97) | 26 (76) | 0.02 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms, n (%) | 33 (50) | 9 (28) | 24 (71) | 0.001 |

| Respiratory symptoms, n (%) | 11 (17) | 9 (28) | 2 (6) | 0.02 |

| Skin rash, n (%) | 13 (20) | 9 (28) | 4 (12) | 0.08 |

| Chest pain, n (%) | 58 (88) | 26 (81) | 32 (94) | 0.1 |

| ECG | ||||

| Normal, n (%) | 6 (9) | 1 (3) | 5 (15) | |

| ST-elevation, n (%) | 40 (61) | 19 (59) | 21 (62) | |

| Ripolarization abnormalities, n (%) | 14 (21) | 8 (25) | 6 (18) | |

| ECG informations not available, n (%) | 6 (9) | 4 (13) | 2 (6) | 0.3 |

| fQRS, n (%) | 22 (79) | 11 (69) | 11 (84) | 0.4 |

| Rhythm disturbance, n (%) | 15 (23) | 11 (34) | 4 (12) | 0.04 |

| EF at admission (%), median (25th-75th) | 45 (35–55) | 35 (20–45) | 50 (45–58) | <0.001 |

| CMRI available, n (%) | 28 (42) | 7 (22) | 21 (62) | – |

| Histopathology available, n (%) | 10 (15) | 8 (25) | 2 (6) | 0.03 |

| ICU, n (%) | 30 (45) | 27 (84) | 3 (9) | <0.001 |

| PCR peak (mg/L), median (25th-75th) | 72 (32–125) | 39 (17–160) | 81 (47–124) | 0.3 |

| Troponin peak (ratio), median (25th-75th) | 98 (24–556) | 197.5 (53–700) | 72 (17–413) | 0.1 |

| Complete recovery, n (%) | 43 (65) | 16 (50) | 27 (79) | 0.02 |

| Partial recovery, n (%) | 14 (21) | 9 (28) | 5 (15) | 0.2 |

| Death, n (%) | 9 (13) | 8 (25) | 1 (3) | 0.01 |

Fig. 4.

Flowchart summarizing the outcomes of patients with bacterial myocarditis according to the syndrome at presentation.

Patients with gastrointestinal involvement were the youngest, with an average age of 25 years20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 and always had negative blood cultures, while those with urogenital infection were the oldest, with an average age of 50 years (28.5–64.5) (p = 0.009).

Overall, 37 patients (56%) fulfilled the predefined criteria for probable or definite myocarditis, while the rest were deemed to have possible myocarditis according to the aforementioned criteria. A minority of reports (10; 15%) provided histopathological data, 9 of which were diagnostic for myocarditis, mostly within the subset presenting with sepsis (8 out of 32 (25%) vs 1 out of 34 (3%), p = 0.006).

The overall median LVEF at admission was 45%,20,35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53 and patients with sepsis had significantly lower values (35%20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 vs 50%39,44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56; (p < 0.001)).

Accordingly, the percentage of patients admitted to the ICU and mortality rate were significantly higher in this subset of patients (27 (84%) vs 3 (9%), p < 0.001, and 8 (25%) vs 1 (3%), p = 0.01, respectively).

Similarly, patients who had severe sepsis demonstrated a lower percentage of complete recovery (16 (50%) vs 27 (79%), p = 0.02).

Overall 15 patients had rhythm disturbances, 11 among those presenting with severe sepsis/septic shock. In particular, 7 patients had sustained ventricular tachycardia (heart rate between 150 and 250), two patients complicated with ventricular fibrillation, in two patients not sustained ventricular tachicardia was recorded without mention of further details and 3 patients had complete AV block. In two cases AV block preceded progressive infra-hisian conduction impairment that eventually led to cardiac arrest.

In the univariate comparison between patients with and without a diagnosis of myocarditis, no differences were observed with respect to demographic, clinical presentation, LVEF and laboratory data, but rhythm disturbances were more prevalent in the former group 12 (32%) vs 3 (10%); p = 0.04 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate comparison of patients with or without ascertained diagnosis of myocarditis.

| Diagnosis ascertained (n = 37) | Diagnosis not ascertained (n = 29) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (25th-75th) | 32 (21–42) | 34 (25–47) | 0.2 |

| Male, n (%) | 30 (81) | 21 (72) | 0.5 |

| EF at admission (%), median (25th-75th) | 45 (35–55) | 45 (35–50) | 0.9 |

| CRP peak (mg/L), median (25th-75th) | 106 (30–132) | 55 (46–74) | 0.8 |

| STN Troponin ratio, median (25th-75th) | 120 (26–580) | 84 (20–226) | 0.5 |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 16 (43) | 16 (55) | 0.4 |

| Rhythm disturbances, n (%) | 12 (32) | 3 (10) | 0.04 |

| Organ involvement | |||

| Gastroenteric syndrome, n (%) | 17 (46) | 14 (48) | 0.9 |

| Respiratory syndrome, n (%) | 9 (24) | 5 (17) | 0.5 |

| Articular/Soft tissue, n (%) | 6 (16) | 5 (17) | 0.9 |

| Urogenital, n (%) | 4 (11) | 4 (14) | 0.7 |

| Central nervous system, n (%) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0.9 |

Nine deaths occurred in the whole population. Almost all patients with an ominous prognosis presented with severe sepsis (8 out of 9 (88%) vs 24 out of 57 (42%); p = 0.01).

Furthermore, respiratory syndrome and occurrence of rhythm disturbances, either bradycardia or tachycardia, were associated with death based on the univariate analysis (p = 0.02 and < 0.001, respectively). (Table 6; Fig. 4).

Table 6.

Univariate comparison of clinical variables according to survival.

| Survivors (n = 57) | Not survivors (n = 9) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (25th-75th) | 30 (23–43) | 36 (33–45) | 0.5 |

| Male, n (%) | 46 (80) | 5 (56) | 0.1 |

| EF at admission (%), median (25th-75th) | 45 (35–55) | 31 (20–45) | 0.1 |

| CRP peak (mg/L), median (25th-75th) | 63.5 (35–124) | 74 (8–160) | 0.9 |

| STN Troponin ratio, median (25th-75th) | 94.5 (24–580) | 228 (3–398) | 0.8 |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 24 (42) | 8 (89) | 0.01 |

| Rhythm disturbances, n (%) | 2 (22)∗ | 7 (78) | <0.001 |

| Organ involvement | |||

| Gastroenteric syndrome, n (%) | 30 (52) | 1 (11) | 0.03 |

| Respiratory syndrome, n (%) | 9 (16) | 5 (56) | 0.02 |

| Articular/Soft tissue, n (%) | 9 (16) | 2 (22) | 0.6 |

| Urogenital, n (%) | 7 (12) | 1 (11) | 0.9 |

| Central nervous system, n (%) | 2 (4) | 0 | 0.9 |

Among the patients who survived, 43 (75%) had a complete recovery according to the aforementioned criteria. Older age, sepsis, respiratory involvement, lower LVEF and occurrence of arrhythmia were univariate predictors of incomplete recovery (p = 0.05, p = 0.02, p = 0.01, p = 0.0001 and p = 0.005, respectively). (Table 7; Fig. 5).

Table 7.

Univariate comparison of clinical variables according to recovery rate.

| Complete recovery (n = 43) | Uncomplete recovery (n = 23) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (25th-75th) | 30 (20–42) | 39 (26–51) | 0.05 |

| Male, n (%) | 36 (83) | 15 (65) | 0.1 |

| EF at admission (%), median (25th-75th) | 50 (40–55) | 30 (20–45) | 0.0001 |

| CRP peak (mg/L), median (25th-75th) | 72 (38–123) | 64 (30–125) | 0.8 |

| STN Troponin ratio, median (25th-75th) | 103 (31–629) | 98 (16–228) | 0.3 |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 16 (37) | 16 (70) | 0.02 |

| Rhythm disturbances, n (%) | 5 (12) | 10 (43) | 0.005 |

| Organ involvement | |||

| Gastroenteric syndrome, n (%) | 24 (56) | 7 (30) | 0.07 |

| Respiratory syndrome, n (%) | 5 (12) | 9 (39) | 0.01 |

| Articular/Soft tissue, n (%) | 6 (14) | 5 (22) | 0.5 |

| Urogenital, n (%) | 6 (14) | 2 (9) | 0.7 |

| Central nervous system, n (%) | 2 (5) | 0 | 0.5 |

Fig. 5.

Histogram depicting mortality and recovery rates according to the syndrome at presentation.

At the multivariate logistic regression analysis, LVEF at admission and heart rhythm disturbances remained independently associated with persistence of myocardial depression, odds ratio (OR) 1.1, for each percent unit of LVEF decrease, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.03–1.2, p = 0.004 and OR 6.6, 95% CI 1.35–32.5, p = 0.02, respectively.

5. Discussion

The prevalence of bacterial myocarditis is poorly defined owing to the lack of uniform diagnostic criteria. Furthermore, there is a recognized overlap between myocarditis and aspecific myocardial depression in the context of sepsis.

This pooled analysis confirmed the epidemiological data for the whole group of patients with myocarditis in terms of age at presentation and the significant prevalence of males. The presentation significantly correlated with age, providing the clinicians with an indication of the spectrum of possible bacteria involved. Histological diagnosis was available for only a minority of the patients, with most of these analyses performed from post-mortem examination and from the subset who presented with overt sepsis. Microscopic examination consistently revealed the presence of leucocyte infiltrates, microabscess and necrosis.

Patients with severe sepsis displayed a cluster of bacterial etiology, among which Staphylococcus and Streptococcus spp were relatively more prevalent, and respiratory symptoms were the most frequent at presentation. This subset of patients was characterized by a higher mortality, a lower recovery rate, a lower LVEF at admission and a higher rate of rhythm disturbances. We hypothesize that pathological myocardial involvement during bacterial sepsis is secondary to metastatic spread of infection from the primary focus, leading to architectural disruption of the myocardium. This concept may be confirmed by the histopathological data, which showed that eight of the ten patients for whom tissue samples were available, presented with sepsis, microabscess and necrosis, which is consistent with bacterial dissemination. In the other two patients, without sepsis, tissue specimens showed localized mycobacterial infection and the absence of direct signs of infection respectively.57,59

The occurrence of rhythm disturbances seems to be the unique variable that was more specifically associated with definite/probable diagnosis of myocarditis, while demographic, clinical and echocardiographic findings were not. In particular, electrocardiographic changes are usually considered to be non-specific findings. In our two cases, we observed the appearance of QRS fragmentation (Fig. 1B, C, E). This feature has been hypothesized to indicate the expression of localized slowing of electrical conduction and correlates with the presence of LGE on CMR.3

Although this finding was not clearly mentioned in any of the reports, it was clearly visible in 22 published ECG (79%), suggesting its reproducible presence across a wide spectrum of etiologies.

6. Conclusion

Bacterial infection is a poorly reported etiologic cause of myocarditis. Diagnosis can be particularly challenging as it can be misled by aspecific transiently depressed myocardial contractility. Within this wide spectrum, apart from the occurrence of brady/tachyarrhythmias, no non-invasive diagnostic modalities appeared to support the specific diagnosis of myocarditis. Bacterial myocarditis may present in the context of severe sepsis. According to this pooled cohort, it is likely the consequence of dissemination of bacteria from the primary infection site to the heart and portend a poorer prognosis in terms of survival and recovery rate.

7. Limitations

This paper has several limitations. Firstly, data were pooled from a limited number of case reports displaying significant heterogeneity in terms of diagnostic criteria, which did not allow for the use of formal quantitative meta-analysis techniques. Secondly, the relatively small number of patients limits the reproducibility and generalizability of the inferences about the prognostic determinants. Furthermore, the diagnosis was based on histopathological criteria in only a few patients.

Funding

No funding was received.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Caforio A.L.P., Pankuweit S., Arbustini E. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2636. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wasi F., Shuter J. Primary bacterial infection of the myocardium. Front Biosci. 2003;8:228–231. doi: 10.2741/1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrero P., Piazza I., Grosu A., Brambilla P., Sironi S., Senni M. QRS fragmentation as possible new marker of fibrosis in patients with myocarditis. Preliminary validation with cardiac magnetic resonance. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:1160–1161. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sikary A.K., Mridha A.R., Behera C. Sudden death of a child due to pyogenic bacterial myocarditis. Med Leg J. 2017;85:105–107. doi: 10.1177/0025817216682187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozkaya G., Shorbagi A., Ulger Z. Invasive group A streptococcal infection with pancarditis caused by a new emm-type 12 allele of Streptococcus pyogenes. J Infect. 2006;53:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domínguez F., Cobo-Marcos M., Guzzo G. Erysipelas and acute myocarditis: an unusual combination. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:1138. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee Y.P., Hoi W.H., Wong R.C. A case of myopericarditis in a patient with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:242–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan B., Strate R.W., Hellman R. Myocardial abscess and fatal cardiac arrhythmia in a hemodialysis patient with an arterio-venous fistula infection. Semin Dial. 2007;20:452–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elias T., Roberts I., Jones N., Sabharwal N., Leeson P. Suppurative bacterial myocarditis: echocardiographic and pathological findings. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:489. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouneb R., Mellouli M., Regaieg H., Majdoub S., Chouchène I., Boussarsar M. Meningococcemia complicated by myocarditis in a 16-year-old young man: a case report. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;29:149. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.29.149.13107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gawalkar A.A., Tale S., Chhabria B.A., Bhalla A. Myocarditis and purpura fulminans in meningococcaemia. QJM. 2017;110:755–756. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcx144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al Shamkhani W., Ajaz Y., Saeed Jafar N., Roy Narayanan S. Myocarditis and rhabdomyolysis in a healthy young man caused by Salmonella gastroenteritis. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/954905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Childs L., Gupta S. Salmonella enteritidis induced myocarditis in a 16-year-old girl. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007628. bcr-2012-007628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villablanca P., Mohananey D., Meier G., Yap J.E., Chouksey S., Abegunde A.T. Salmonella Berta myocarditis: case report and systematic review of non-typhoid Salmonella myocarditis. World J Cardiol. 2015;7:931–937. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i12.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-aqeedi R.F., Kamha A., Al-aani F.K., Al-ani A.A. Salmonella myocarditis in a young adult patient presenting with acute pulmonary edema, rhabdomyolysis, and multi-organ failure. J Cardiol. 2009;54:475–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Türoff A., Vollnberg H., Kohler B.M. Acute myocarditis after visiting Pakistan. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;133:1493–1496. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1081096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komuro J., Ueda K., Kaneko M., Nitta S., Kasao M., Yokoyama M. Various cardiac abnormalities caused by bacterial myocarditis. Int Heart J. 2018;59:229–232. doi: 10.1536/ihj.16-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gentile G., Meles E., Carbone C., Gantú E., Maggiolini S. Unusual case of myocardial injury induced by Escherichia coli sepsis. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2010;74:40–43. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2010.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen T.C., Lu P.L., Lin C.Y., Lin W.R., Chen Y.H. Escherichia coli urosepsis complicated with myocarditis mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med Sci. 2010;340:332–334. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181e92e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Cock D., Hiltrop N., Timmermans P., Dymarkowski S., Van Cleemput J. Myocarditis associated with Campylobacter enteritis: report of three cases. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:19–21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.964882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pena L.A., Fishbein M.C. Fatal myocarditis related to Campylobacter jejuni infection: a case report. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2007;16:119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kushawaha A., Brown M., Martin I., Evenhuis W. Hitch-hiker taken for a ride: an unusual cause of myocarditis, septic shock and adult respiratory distress syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson P.A., Tierney L., Lai K., Graves S. Queensland tick typhus: three cases with unusual clinical features. Int Med J. 2013;43:823–825. doi: 10.1111/imj.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roch N., Epaulard O., Pelloux I. African tick bite fever in elderly patients: 8 cases in French tourists returning from South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:28–35. doi: 10.1086/589868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou Y., Lin L., Xiao H., Xiang D. A rare case of toxic myocarditis caused by bacterial liver abscess mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Am J Case Rep. 2016;17:1–5. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.895350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chuang T.Y., Lin C.J., Lee S.W. Rapidly fatal community-acquired pneumonia due to Klebsiella pneumoniae complicated with acute myocarditis and accelerated idioventricular rhythm. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2012;45:321–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ladani A.P., Biswas A., Vaghasia N., Generalovich T. Unusual presentation of listerial myocarditis and the diagnostic value of cardiac magnetic resonance. Tex Heart Inst J. 2015;42:255–258. doi: 10.14503/THIJ-14-4204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haddad F., Berry G., Doyle R.L., Martineau P., Leung T.K., Racine N. Active bacterial myocarditis: a case report and review of the literature. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:745–749. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pushpakumara J., Prasath T., Samarajiwa G., Priyadarshani S., Perera N., Indrakumar J. Myocarditis causing severe heart failure-an unusual early manifestation of leptospirosis: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:80. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1031-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morgan A.M., Roden R.C., Matson S.C., Wallace G.M., Lange H.L.H., Bonny A.E. Severe sepsis and acute myocardial dysfunction in an adolescent with Chlamydia trachomatis pelvic inflammatory disease: a case report. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2018;31:143–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoefer D., Poelzl G., Kilo J. Early detection and successful therapy of fulminant chlamydia pneumoniae myocarditis. Am Soc Artif Intern Organs J. 2005;51:480–481. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000169077.53643.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suesaowalak M., Cheung M.M., Tucker D., Chang A.C., Chu J., Arrieta A. Chlamydophila pneumoniae myopericarditis in a child. Pediatr Cardiol. 2009;30:336–339. doi: 10.1007/s00246-008-9301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Efe C., Can T., Ince M., Tunca H., Yildiz F., Sennaroglu E. A rare complication of Brucella infection: myocarditis and heart failure. Intern Med. 2009;48:1773–1774. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Royston A.P., Gosling O.E. Patient with native valve infective endocarditis and concomitant bacterial myopericarditis. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-224907. bcr-2018-224907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aguirre J.L., Jurado M., Porres-Aguilar M. Acute nonrheumatic streptococcal myocarditis resembling ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction in a young patient. SAVE Proc. 2015;28:188–190. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2015.11929224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sundbom P., Suutari A.M., Abdulhadi K., Broda W., Csegedi M. Salmonella enteritidis causing myocarditis in a previously healthy 22-year-old male. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2018;2018:106. doi: 10.1093/omcr/omy106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hibbert B., Costiniuk C., Hibbert R. Cardiovascular complications of Salmonella enteritidis infection. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26:323–325. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(10)70444-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palombo M., Margalit-Yehuda R., Leshem E., Sidi Y., Schwartz E. Near-fatal myocarditis complicating typhoid fever in a traveler returning from Nepal. J Trav Med. 2013;20:329–332. doi: 10.1111/jtm.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams P., Lainchbury J. Enteritis-associated myocarditis. Heart Lung Circ. 2004;13:106–109. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uribarri A., Martínez-Sellés M., Yotti R., Pérez-David E., Fernández-Avilés F. Acute myocarditis after urinary tract infection by Escherichia coli. Int J Cardiol. 2011;152:33–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inayat F., Ali N.S., Riaz I., Virk H.U.H. From the gut to the heart: Campylobacter jejuni enteritis leading to myopericarditis. Cureus. 2017;9:1326. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hessulf F., Ljungberg J., Johansson P.A., Lindgren M., Engdahl J. Campylobacter jejuni-associated perimyocarditis: two case reports and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:289. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1635-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Panikkath R., Costilla V., Hoang P. Chest pain and diarrhea: a case of Campylobacter jejuni-associated myocarditis. J Emerg Med. 2014;46:180–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fica A., Seelmann D., Porte L., Eugenin D., Gallardo R. A case of myopericarditis associated to Campylobacter jejuni infection in the southern hemisphere. Braz J Infect Dis. 2012;16:294–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kratzer C., Wolf F., Graninger W., Weissel M. Acute cardiac disease in a young patient with Campylobacter jejuni infection: a case report. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2010;122:315–319. doi: 10.1007/s00508-010-1381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nevzorov R., Shleyfer E., Gourevitch A., Jotkowitz A., Porath A., Barski L. Campylobacter-associated myopericarditis with ventricular arrhythmia in a young hypothyroid patient. Isr Med Assoc J. 2010;12:505–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heinzl B., Köstenberger M., Nagel B., Sorantin E., Beitzke A., Gamillscheg A. Campylobacter jejuni infection associated with myopericarditis in adolescents: report of two cases. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:63–65. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-0985-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turley A.J., Crilley J.G., Hall J.A. Acute myocarditis secondary to Campylobacter jejuni enterocolitis. Resuscitation. 2008;79:165–167. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kotilainen P., Lehtopolku M., Hakanen A.J. Myopericarditis in a patient with Campylobacter enteritis: a case report and literature review. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38:549–552. doi: 10.1080/00365540500372903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cunningham C., Lee C.H. Myocarditis related to Campylobacter jejuni infection: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2003;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hannu T., Mattila L., Rautelin H., Siitonen A., Leirisalo-Repo M. Three cases of cardiac complications associated with Campylobacter jejuni infection and review of the literature. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;24:619–622. doi: 10.1007/s10096-005-0001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cox I.D., Fluck D.S., Joy M.D. Campylobacter myocarditis; loose bowels and a baggy heart. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001;3:105–107. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(00)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Revilla-Martí P., Cecilio-Irazola Á., Gayán-Ordás J., Sanjoaquín-Conde I., Linares-Vicente J.A., Oteo J.A. Acute myopericarditis associated with tickborne Rickettsia sibirica mongolitimonae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:2091–2093. doi: 10.3201/eid2312.170293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Silva J.T., López-Medrano F., Fernández-Ruiz M. Tickborne lymphadenopathy complicated by acute myopericarditis, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:2240–2242. doi: 10.3201/eid2112.150672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Doyle A., Bhalla K.S., Jones J.M., 3rd, Ennis D.M. Myocardial involvement in rocky mountain spotted fever: a case report and review. Am J Med Sci. 2006;332:208–210. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200610000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bellini C., Monti M., Potin M., Dalle Ave A., Bille J., Greub G. Cardiac involvement in a patient with clinical and serological evidence of African tick-bite fever. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Silingardi E., Rivasi F., Santunione A.L., Garagnani L. Sudden death from tubercular myocarditis. J Forensic Sci. 2006;51:667–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dellegrottaglie S., Russo G., Damiano M. A case of acute myocarditis associated with Chlamydia trachomatis infection: role of cardiac MRI in the clinical management. Infection. 2014;42:937–940. doi: 10.1007/s15010-014-0631-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mavrogeni S., Manoussakis M., Spargias K., Kolovou G., Saroglou G., Cokkinos D.V. Myocardial involvement in a patient with chlamydia trachomatis infection. J Card Fail. 2008;14:351–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carrascosa M.F., Pascual Velasco F., Gómez Izquierdo R., Salcines-Caviedes J.R., Gómez Amigo V., Canga-Villegas A.M. Acute Q fever myocarditis: thinking about a life-threatening but potentially curable condition. Int J Cardiol. 2012;158:17–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paz A., Potasman I. Mycoplasma-associated carditis. Case reports and review. Cardiology. 2002;97:83–88. doi: 10.1159/000057677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]