Abstract

Policy Points.

Community‐engaged research (CEnR) engenders meaningful academic‐community partnerships to improve research quality and health outcomes. CEnR has increasingly been adopted by health care systems, funders, and communities looking for solutions to intractable problems.

It has been difficult to systematically measure CEnR's impact, as most evaluations focus on project‐specific outcomes. Similarly, partners have struggled with identifying appropriate measures to assess outcomes of interest.

To make a case for CEnR's value, we must demonstrate the impacts of CEnR over time. We compiled recent measures and developed an interactive data visualization to facilitate more consistent measurement of CEnR's theoretical domains.

Context

Community‐engaged research (CEnR) aims to engender meaningful academic‐community partnerships to increase research quality and impact, improve individual and community health, and build capacity for uptake of evidence‐based practices. Given the urgency to solve society's pressing public health problems and increasing competition for funding, it is important to demonstrate CEnR's value. Most evaluations focus on project‐specific outcomes, making it difficult to demonstrate CEnR's broader impact. Moreover, it is challenging for partnerships to identify assessments of interest beyond process measures. We conducted a mapping review to help partnerships find and select measures to evaluate CEnR projects and to characterize areas where further development of measures is needed.

Methods

We searched electronic bibliographic databases using relevant search terms from 2009 to 2018 and scanned CEnR projects to identify unpublished measures. Through review and reduction, we found 69 measures of CEnR's context, process, or outcomes that are potentially generalizable beyond a specific health condition or population. We abstracted data from descriptions of each measure to catalog purpose, aim (context, process, or outcome), and specific domains being measured.

Findings

We identified 28 measures of the conditions under which CEnR is conducted and factors to support effective academic‐community collaboration (context); 43 measures evaluating constructs such as group dynamics and trust (process); and 43 measures of impacts such as benefits and challenges of CEnR participation and system and capacity changes (outcomes).

Conclusions

We found substantial variation in how academic‐community partnerships conceptualize and define even similar domains. Achieving more consistency in how partnerships evaluate key constructs could reduce measurement confusion apparent in the literature. A hybrid approach whereby partnerships discuss common metrics and develop locally important measures can address CEnR's multiple goals. Our accessible data visualization serves as a convenient resource to support partnerships’ evaluation goals and may help to build the evidence base for CEnR through the use of common measures across studies.

Keywords: community‐engaged research, action research, measurement, outcomes, mapping review

While the traditional approach to health research treats individuals and populations as the subjects of inquiry, community‐engaged research (CEnR) involves establishing and maintaining authentic partnerships between researchers and those who are being researched, including local community members and organizations. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 CEnR is an umbrella term used to describe a range of activities and approaches (eg, stakeholder engagement, patient engagement, public involvement, participatory action research), with community‐based participatory research (CBPR) being the longest standing and best known of these related to health. 6 Yet, all approaches to CEnR borrow from CBPR's emphasis on community members as equal partners in many aspects of the research process, from the identification and selection of priority topics and research questions, to developing data collection materials and analytical strategies, to drafting and disseminating the publication of findings. 1 , 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 In addition, CEnR often aims to build the future capacity of academic‐community partnerships by improving community members’ research literacy and researchers’ concurrent understanding of the community's history and needs. 2 , 3 , 5 , 11

CEnR is theorized to impact research evidence and community health outcomes through a number of different mechanisms. 1 , 3 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 For example, including community input into research design is likely to result in evidence and subsequent interventions that are more applicable to the community's needs and thus, more readily accepted by the community. 12 , 14 , 16 , 17 Community input can also improve the translation of research findings to practice by providing evidence that is tailored to the setting and population of interest. 1 , 3 , 13 , 14 Similarly, community members are likely to greatly improve the translation and dissemination of research evidence by championing the findings within the community and suggesting alternatives to publication. 11 , 16 , 20 Finally, the process of CEnR can build trust and mutual respect and facilitate future research participation, especially in populations that have traditionally been mistreated by or excluded from health research. 11 , 12 , 15 , 16 , 19

The potential impacts of CEnR on population health outcomes are less established in the literature. Yet, engaged research is theorized to empower community members to become educated about their own health and activated to participate in their health care. 12 Engagement in research may also lead community members to make better health decisions based on the knowledge uncovered, which can improve long‐term health outcomes. 17 Finally, participation in engaged research may contribute to greater community acceptance of research, subsequently guiding community action. 12

Much of the literature on participatory approaches has relied on case studies, qualitative inquiry, or literature review to suggest conceptual models and best practices for conducting engaged research. 11 , 16 , 18 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 Although many proximal and distal outcomes are assumed to be affected by community engagement, there is, in fact, little evidence in the literature to demonstrate these relationships. Recent systematic reviews have shown that popular evaluation techniques are to (a) count the number of participants involved in engaged projects or events, 25 or (b) elicit researcher and community member impressions of the impact of participation through qualitative approaches such as interviews or focus groups, 10 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 which, while valuable, limits the ability to systematically measure change and compare outcomes across studies. Some CEnR projects have developed their own limited‐item scales to assess the short‐term health outcomes or processes most relevant to the particular researcher‐community partnership. 25 , 30 The selection of locally relevant tools is essential to the practice of CEnR as it allows researchers and community members to share control of all stages of the research process, including which outcomes are most relevant to the partnership. 31 Nevertheless, the reliance on local tools impedes the comparison of outcomes across studies or the validation of broader CEnR constructs, which could help to strengthen the impact of the field and increase recognition of CEnR as a scientific endeavor. 32 To achieve CEnR's broader goals of improved health and research, there may be value in partnerships utilizing common or broadly generalizable measures of engagement in projects alongside locally tailored tools. We encourage partnerships to consider the multiple aims of CEnR when discussing evaluation practices to assess their projects.

CEnR approaches have been increasingly adopted by health care systems, funders, and communities looking for solutions to seemingly intractable problems. 13 , 17 , 22 , 33 Although researchers and community members who have partnered can attest to the benefits of CEnR, there is a growing emphasis in health research on funding evidence‐based interventions. 34 Thus, it is more important than ever for engaged partnerships to demonstrate evidence of the positive impacts of CEnR. To facilitate consistent measurement of the impact of engaged research across projects over time and contribute to a clearer understanding of the value of community engagement, our aims were to:

Identify and categorize evaluation tools or measures of community engagement contexts, processes, and outcomes that can be used across a variety of CEnR projects in conjunction with locally tailored measures

Characterize current gaps in measurement

Serve as a resource for future CEnR projects

Methods

Search Strategy

To achieve our stated aims, we opted to conduct a mapping review. Mapping reviews categorize existing literature according to a particular theoretical model, participant population, or setting. This allows the reviewers to identify gaps in the literature, which can inspire further reviews or primary research. 35 , 36 In addition, mapping reviews often present results in a user‐friendly visual format to support future work. 35 , 36

To ensure a comprehensive search for measures of engagement, we adopted multiple strategies. First, we scanned the peer‐reviewed literature using two popular electronic bibliographic databases: Web of Science (including Medline/PubMed), and Academic Search Premier (including PsycINFO). The Web of Science Core Collection includes citations across the social science disciplines, allowing for a search across an index of 148 sociology, 140 psychology, 90 anthropology, and 82 health policy/services peer‐reviewed journals as examples. 37 Academic Search Premier similarly indexes across more than 3,900 peer‐reviewed journals across disciplines. 38 We limited our search to include only English‐language articles published between January 2009 and December 2018, as other reviews have targeted earlier time frames. 16 , 29 , 39 , 40 , 41 Four separate searches were conducted; search terms were entered into the databases using quotation marks and included (1) community‐engaged research AND evaluation, (2) stakeholder‐engaged research AND evaluation, (3) community‐based participatory research AND evaluation, and (4) participatory action research AND evaluation for a total of 2,708 abstracts to review (1,399 via Web of Science and 1,309 via Academic Search Premier).

The lead author (T.L.) reviewed each title and abstract to eliminate duplicate records, study protocols, and those that diverged from community member, stakeholder, patient, or public engagement in research (n = 1,666). At this stage, the following inclusion criteria were also applied: (a) the study must describe an assessment or evaluation (qualitative or quantitative) of an engaged project, thus excluding articles that only described conceptual models or practical steps for conducting engaged research (n = 482), and (b) the assessment or evaluation must measure the context, process, or outcome of engaged research. These evaluation targets were selected based on the theoretical and practical premise that understanding the context and process of engaged research is critical to interpreting the ultimate impact. 16 , 27 In addition, we aimed to uncover a body of “universal” measures that could be used by partnerships consistently across studies in addition to locally tailored tools. Thus, the lead author excluded articles where the only results reported were study‐specific and would not readily generalize to other engaged research settings. These included varied outcomes such as blood glucose level in a diabetes population, environmental health literacy in a sample of school children, or level of trauma awareness in a clinician group (to name a few) (n = 353). Although this decision likely excludes a number of specific health‐related items that could be useful for some engaged partnerships, it was not feasible to include and analyze the wide breadth of study‐specific outcomes in this particular review.

As a secondary approach, we conducted a scan of “community‐engaged research organizations” (via Google search and discussions with colleagues engaged in CEnR) to identify academic centers and working groups actively pursuing engaged research; we searched these organizations’ websites for additional evaluation resources and tools not captured by the bibliographic databases. This yielded a total of 25 additional white papers and instruments. Thus, the full text of 126 articles and white papers were obtained and reviewed to glean specific qualitative and quantitative assessments. After eliminating all papers that did not describe the measurement scales or items used (n = 57), this left a total of 69 final measures for data abstraction.

Data Abstraction, Validation, and Visualization

The lead author abstracted data from the individual study authors’ own descriptions of (a) the purpose of the measure, and (b) the domains measured. Additionally, the lead author classified the measures according to whether the study authors’ stated purpose or goal of the measure most aligned with a context evaluation (examining the conditions in which CEnR will be conducted), process evaluation (examining how the engagement is done), or outcome/impact evaluation (examining the intended effects). 16 , 27 Measures were also allowed to represent multiple goals—for example, a measure of how partnership conflict was resolved could be used during engagement to measure the process and postengagement to determine if a change has occurred—if indicated in the study author's stated purpose and the item descriptions of each subscale or subsection. Our aim in allowing measures to serve in multiple evaluation categories is for academic‐community partners to consider these measures according to what would be useful for their specific contexts.

If an article did not include a discussion of the measure's domains, the measure's items were summarized with key phrases to provide a cross‐item description. To validate the data abstraction, the other two authors (A.H. and G.T.) each independently coded half of the measures as described, so that all 69 measures were reviewed by two authors. All three authors met biweekly to arbitrate coding conflicts through consensus. The authors also maintained individual process memos to highlight patterns and themes within the data. Selected measures from each evaluation type (context, process, and outcome) can be found in Appendix Table 1. The full 69 measures are represented in Online Supplemental Table 1.

To serve as a resource for future CEnR projects, we utilized Tableau Public to produce interactive data visualizations of the discovered measures and the domains represented. 42 Through this visual display, we hope to support researchers and community members to identify measures of engagement to use in their own CEnR projects, according to their own goals. We encourage readers to explore this resource at https://public.tableau.com/profile/tana.luger#!/vizhome/MeasuresofCommunityEngagement/AuthorsandDomains.

Results

Across the literature and measures reviewed, we found substantial variation in how researchers conceptualized and defined domains to measure. For example, the academic‐community partnership central to CEnR has been described in the literature with such disparate phrases as “reciprocal relationships,” 19 “collaborative partnerships,” 5 “mutually effective partnerships,” 19 “mutual respect and acceptance of differences,” 43 and “shared power and decision‐making,” 13 , 44 , 45 among others. In addition, nearly half (47.8%, n = 33) of the included measures could be applicable to more than one domain (ie, context, process, or outcome evaluations).

We found the boundaries between core CEnR concepts were similarly unclear. For example, although many studies attempted to evaluate the role that community members had adopted within the engaged research, the scope of the evaluation varied significantly. Some studies asked community members to quantify the specific tasks in which they engaged. 46 , 47 Some focused on the community members’ roles in the research and communication processes that promote role clarity. 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 Still other studies focused on the community's perception of the impact that their specific activities had on the research project. 52 , 53 , 54

In order to place our results within the context of the larger literature and characterize gaps, we present a brief table of the systematic reviews (n = 12) that were uncovered utilizing our specific search criteria (see Appendix Table 2). As our aim was not to conduct a review of reviews, but to discover measures of engagement, it is important to note that these 12 are not an exhaustive representation of the previously reviewed literature. Nevertheless, the authors of the included systematic reviews frequently call for the need to develop reliable and valid measures in order to better understand contextual factors, partnerships, and the impacts of engagement. Many of the systematic reviews also acknowledge the value of quantitative and qualitative measurement for better analyzing engagement processes.

Context Measures

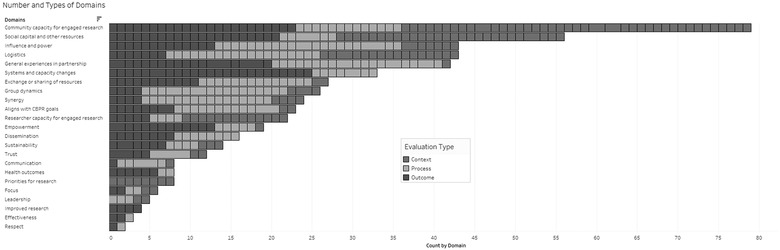

We identified 28 measures that assess the context of engaged research (see Figure 1); these measures predominantly focus on the conditions under which the research will be conducted and considerations for effective collaborations between researchers and community members. The majority of context measures evaluate the community's capacity for engaged research (see Figure 2), including training and past CEnR experiences. For example, a quantitative needs assessment by Goytia and colleagues. inquires about the experiences of community organizations in research and evaluation, their interest in building specific research skills like survey development or literature review, and interest in partnering in the future. 55 Similarly, the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement's tool encourages community organizations to self‐evaluate their capacity to utilize research evidence, a key skill for active participation in an engaged project. 56 In addition, a survey by Rubin and colleagues asks community members to assess their level of confidence in working with researchers as well as motivations and attitudes toward research. 57 Many context measures also assess the strengths and resources of the community that may be brought to bear in an engaged research project such as social capital and organizational linkages. A qualitative interview guide by Gibbons and colleagues encourages community members to reflect on the strengths within the community that may be drawn on for an academic‐community partnership. 58 This includes a variety of community resources such as social groups, occupations, and sources of information. In addition, the Partnership River of Life participatory exercise published by Sanchez‐Youngman and Wallerstein encourages partners to develop a “communal narrative” about the origins and key events of their partnership in order to better understand the larger historical, social, political, and economic context in which the partnership is aiming to function. 59

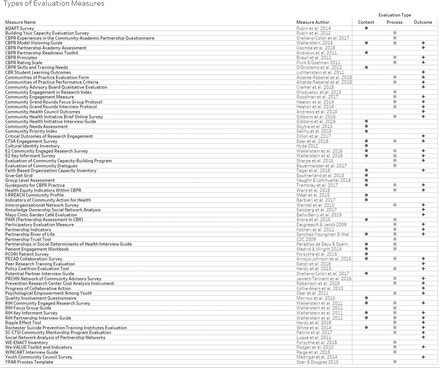

Figure 1.

Engagement Measures by Evaluation Type

For interactive data visualization, please visit https://public.tableau.com/profile/tana.luger#!/vizhome/MeasuresofCommunityEngagement/AuthorsandDomains.

Figure 2.

Number of Domains Represented in Engagement Measures by Evaluation Type

For interactive data visualization, please visit https://public.tableau.com/profile/tana.luger#!/vizhome/MeasuresofCommunityEngagement/AuthorsandDomains.

Several measures evaluate the academic researcher's capacity for engaged research, such as researchers’ sufficient knowledge and understanding of the community or expectations and goals for engagement. The Engage for Equity Key Informant survey asks partners to rate whether the principal investigator of an engaged project is from a similar cultural background as the targets of the project and whether the project has provided any training or discussions about oppression and cultural sensitivity. 60 Another survey, this one by DiGirolamo, asks researchers to assess their current skills and interests related to conducting CBPR (such as coalition‐building or how to obtain funding) for the purpose of uncovering needed academic infrastructure to support CBPR projects. 61

Finally, a few context measures encourage reflection on the specific logistics of an engaged project before it begins. For example, the Patient Engagement Workbook takes researchers through a number of important considerations for engaged research with patients, including the patient's role across the stages of research, methods to identify and recruit patient partners, institutional requirements, how patient concerns will be addressed, and processes for sharing data. 49 As another example, the Community Priority Index allows researchers and community members to rate the importance and ease of change of community issues in order to quantify the partnership's priorities for engaged research projects. 62

Process Measures

We identified 43 measures that evaluate the process of engaged research—ie, aspects of how community engagement occurred (see Figure 1). Manyprocess measures examine group dynamics within the partnership, 20 , 44 , 45 , 48 , 53 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 typically adapted from a 2003 instrument by Schulz, Israel, and Lantz. 68 For example, interview questions by Paige and colleagues elicit community members’ general experiences in the partnership to characterize the academic‐community collaboration. 67

Following the overarching goals of CEnR, many measures inquire about perceptions of influence and power, respect, trust, and communication across group interactions to ensure an equitable collaboration. 44 , 45 , 48 , 52 , 53 , 69 For example, the Youth‐led Participatory Action Research Process Template allows team members to rate the power‐sharing observed between teachers and students during an engaged project. 70 The Partnership Assessment in Community‐based Research (PAIR) survey encourages stakeholders to assess the fundamental characteristics of a strong partnership, including open and honest communication, equitable collaboration, shared partnership values such as mutual respect and trust, and a plan for sustaining the partnership. 43 In addition, quantitative measures by Braun and colleagues and Goodman and colleagues allow stakeholders to reflect whether the processes utilized within their partnership align with the goals of community‐based participatory research (CBPR). 64 , 65 The partnership is rated on the basis of how well or how often it “fosters capacity‐building for all partners” and “seeks and uses the input of community partners,” among others. 65 These measures allow stakeholders to determine whether the engaged project is being conducted in the spirit of equitable, collaborative CEnR.

Another body of measures examine partnership synergy, or enhanced collaboration among partner members. For example, the CBPR Rating Scale by Pivik and Goelman asks partners to rate the importance of shared decision making, goals, and values to their engaged work. 71 Similarly, the Engage for Equity Community Engaged survey encourages partners to assess the level at which they develop shared goals and strategies and respond to challenges and community needs. 60

Another process survey measures the practicalities of the engaged project, such as satisfaction with the organization and structure of project meetings. 53 Other measures examine the leadership in place for the engaged research, assessing the effectiveness of leadership and outlining governance decisions. 43 , 48 , 72 The Engage for Equity Community Engaged survey also asks respondents about project governance, such as who approved participation in the project on behalf of the community and who controlled project resources. 60 Such measures would be useful for obtaining feedback to inform effective partnership strategies for future engaged research.

Outcome and Impact Measures

We identified 43 measures that evaluate the outcome or impact of engaged research or the intended effects of community engagement (see Figure 1). Although a number of measures ask open‐ended questions about the benefits and challenges of participating in engaged research, 20 , 44 , 73 others more formally assess the perceived benefits of engaged research through survey methods in order to elicit reported impacts and costs within each academic‐community partnership. 51 , 52 , 53 , 58 Often, this involves asking stakeholders directly about their satisfaction with the partnership. 52 , 53

The majority of included outcome measures evaluate the systems and capacity changes produced by the engaged research, such as increased information and resource exchange among stakeholders, 44 , 74 , 75 joint activities or events, 75 ongoing or new funding for partnered work, 72 and improvements to services and programs. 48 Others focus especially on measuring improved community capacity for research, such as the knowledge and skills for future research engagement 51 , 53 , 73 , 76 as well as self‐efficacy and confidence in research participation. 70 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80

Similarly, many measures appraise the sustainability of the partnership by gauging stakeholder commitment to the work, 43 , 48 , 53 , 65 ongoing funding, 48 , 72 and enhanced research networks. 52 Still others quantify the number of publications, policy revisions, and solicited funding opportunities to judge the effectiveness of the partnership's efforts. 60 , 72 , 81 Yet, few measures in our sample directly assessed how engagement improved research practice or outcomes. The CBPR Model Visioning Guide encourages stakeholders to consider research productivity (ie, papers, grant applications, and awards) as an intermediate outcome, if applicable to their CBPR partnership. 82

Some measures examined more distal outcomes of the project such as policy changes 60 , 83 , 84 , 85 or community empowerment. For example, the Knowledge Ownership Social Network Analysis asks partners to rank stakeholders according to whether they held important information relating to the project. 74 Meant to be conducted longitudinally, the measure allows partners to track whether knowledge is elicited and owned equitably among stakeholders, reflecting a more active, empowered role of the community. Similarly, the Ripple Effect Tool quantifies the social connectedness or enhanced relationships and resource sharing within an engaged project. 83 Finally, the Engage for Equity Community Engaged survey asks about health outcomes to evaluate longer‐term changes to community health status or health outcomes of interest that may arise from the engaged project. 60

Discussion

Through a mapping review technique and multipronged search, we identified 28 measures appropriate for a context evaluation, 43 process measures, and 43 outcome or impact measures of CEnR that have been developed over the past decade. The majority of the measures assessed community capacity for engaged research, either as a context evaluation to understand the community's skills and resources for engaged work or as an outcome or goal of an engaged project. This is in contrast to two recent systematic reviews, 16 , 29 which found a focus on process measurement.

Our work also supports the assertion of many authors that there is a lack of consensus on the goals of CEnR (see Appendix Table 2); we found substantial variation in how study authors conceptualized and defined even similar domains to measure. Although all measurement is important to understanding the impacts of engaged research, achieving more consistency in the ways that partnerships evaluate key constructs could reduce some of the measurement confusion apparent in the literature. Although many authors have valiantly attempted to systematically organize this complex body of literature, it is still difficult for partnerships to identify measures to use in their engaged projects. In the context of CEnR, it is important to highlight the inherent tension between a researcher‐driven approach to selecting established and validated metrics and a community‐driven process of developing and/or adopting metrics that may be more trusted, relevant, and useful in the local setting. Based on our experiences conducting engaged research, discussions with colleagues and community members, and CEnR's overarching goal of an equitable partnership where no member is more or less important than another, 31 , 86 , 87 it seems that a hybrid approach in which researchers and community members propose and discuss both measures of the broader domains of engaged research and the specific needs and goals of the community allows for both consistency and local tailoring. In addition, a hybrid approach that encourages partnerships to identify common metrics and develop locally important measures may represent a process whereby the desired outcomes of CEnR such as synergy, shared power, and shared ownership can flourish. 88 In that spirit, we hope that the included data visualization will serve as a convenient resource to help academic‐community partnerships identify common measures to consistently include in their projects. Similarly, although many research groups and organizations have attempted to create models to guide the practice of CEnR, 32 , 86 , 89 , 90 more collaborative work needs to be done to promote a consistent framework for engaged research. A clear, guiding model built and tested across settings and data sources, such as the one proposed recently by Oetzel and colleagues, 91 can encourage more systematic measurement of important domains.

In contrast to systematic reviews by Sandoval and colleagues 29 and Esmail, Moore, and Rein, 16 we discovered many context measures, which could indicate a growing interest in understanding the conditions in which CEnR will take place. As described earlier, these measures predominantly assessed the community's capacity for engaging in research, such as skills in literature review or experiences with academic researchers. This is a strong step forward in improving overall measurement of engaged research. As Sandoval and colleagues purport, “differences in context significantly influence processes, which form the core operational partnership features of CBPR. These differences … matter in terms of partnership success.” 29 Thus, understanding the context in which engagement takes place is a critical step in understanding the academic‐community partnership and measuring the impact of engaged research. We recommend that partnerships include measures throughout the life cycle of the engaged project so that the context, processes used, and impacts are all assessed. Ultimately, the strength of the partnership and ability to identify project impacts may be facilitated by carefully made decisions at the project's start to include systematic measurement. Recent toolkits and planning exercises 49 , 82 , 92 , 93 can facilitate equitable participation among stakeholders in this critical stage.

Nevertheless, many of the measures that we uncovered can be used at multiple points in the engaged research; for example, a process measure administered at the start and end of the project may simultaneously represent an evaluation of the engagement process as well as an outcome or impact of the project (eg, change in the partnership or process). Although our goal is to point partnerships toward valid and reliable common measures that can be used across settings, we do not suggest that partnerships rely solely on these measures for evaluation purposes. It is critical for academic‐community partners to have the flexibility to adapt measures to best fit their needs and local settings. Many of the qualitative guides or workbooks that we include in this paper are designed to encourage partnerships to self‐reflect on the type of measurement that best fits their needs. 49 , 82 , 92 , 94 , 95

Encouragingly, we identified a growing number of measures of the outcomes or impacts of engaged research, in contrast to the findings of previous systematic reviews. 16 , 26 , 29 , 40 , 41 In our analysis, investigators chose to measure such outcomes as change in community capacity (eg, increased information exchange or resource sharing), perceptions of whether the project aligned with CBPR principles, the number of activities or goals that the partnership achieved, the perceived benefits of the project, and satisfaction with the project. Although these outcomes can be easily documented from project activities or elicited from participants, there is much more to be done to determine the impact of engaged research. Recent efforts in this direction provide valuable practical guidance for addressing the heterogeneity of impacts in the literature 96 and the challenges of measuring across local settings and partnerships. 32 Similar to multiple reviews, 16 , 26 , 29 , 39 we found a lack of attention to long‐term outcomes such as improved uptake of research or an effect on health outcomes. We recommend that partnerships include both measures of the immediate effect of the research process or project (eg, increased group cohesion) as well as consider follow‐up measurement of more distal outcomes over time.

As previously mentioned, many systematic reviews call for the need to develop psychometrically valid and reliable quantitative measures in order to further understanding of the mechanisms at work (see Appendix Table 2). We agree that it is critical for the field to move toward validation of existing quantitative measures as well as the continued production of new instruments in order to assure that engaged research models and measures are evidence‐based. Nevertheless, we affirm that there is value in including qualitative measurement in engaged research projects, following our choice to include interview and focus group guides in our mapping review. Hearing directly from stakeholders in their own words can lend insight that can lead to better conceptualization and operationalization of engagement. In turn, this can lead to more valid and reliable quantitative measures. Additionally, the nonspecific effects of engagement that are theorized to be influential, such as cohesive relationships or feelings of being valued, may not be fully captured by a 7‐point Likert scale. As Conklin and colleagues mention, “the emphasis placed on assessing outcomes/impact of public involvement risks missing the normative value of public involvement as intrinsically good because it is a deliberative democratic process.” 41 There is likely inherent value in engaging community members in research beyond the targets of any intervention. Integrated qualitative and quantitative measurement may best capture these complex effects.

There are several limitations to our work. Although we relied on multiple strategies to ensure as comprehensive a search for measures as possible, we did not conduct a systematic review, due to the wide scope and ambiguity of the literature. As a result, we may have unintentionally missed a measure for inclusion. In addition, we reviewed only those measures whose individual items were described in the peer‐reviewed or online literature. It is possible that organizations have developed useful measures but have not identified an effective way to share them with other engaged groups. If readers have developed or identified measures for engaged work to recommend, we encourage them to contact the lead author for inclusion in the interactive data visualization.

Conclusion

Researchers and community members who have partnered on research together can attest to the perceived benefits of CEnR; many practical lessons learned and conceptual models can be found in the literature. Simultaneously, CEnR approaches and methods have been taken up by health care systems, funders, and communities looking for solutions to intractable problems, within the context of funding evidence‐based interventions. This means it is more important than ever for those conducting CEnR to be able to demonstrate impacts of CEnR over time, and for the field as a whole to make a case for the value of CEnR. Nevertheless, models and concepts of engaged research still remain muddy. We have compiled a body of recent measures and developed an interactive data visualization to facilitate more consistent measurement of the theoretical domains of CEnR. Along with previous systematic reviews, we hope that our work will support academic‐community partnerships to identify key domains to be measured within their projects and instruments with which to do so.

Appendix Table 1.

Selected Measures of Community Engagement (Organized by Context, Process, or Outcome Evaluation Based on Study Authors’ Descriptions)

| Instrument | Domains Measured | Definitions | Purpose of Measure | Number of Items | Validity/Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selected Context Measures | |||||

| Community‐Based Participatory Research (CBPR) Skills and Training Needs 61 |

|

|

Survey of research investigators’ skills, interest, and training needs in CBPR | 20 closed‐ and open‐ended items | Piloted with academic medicine and public health faculty and then revised |

| Community Needs Assessment 55 |

|

|

Assessment of local community‐based organizations’ research needs | 23 closed‐ and open‐ended items | – |

| Group Level Assessment 97 |

|

|

Formative evaluation method to assess needs and design a plan for future programs | 7 participatory stages/activities | Implementation across more than 14 participatory evaluation settings |

| Community Priority Index 62 |

|

|

Method to quantify priorities (for engaged project) across stakeholders | Varies; issues derived a priori or through community focus groups | – |

| Cultural Identity Inventory 98 |

|

|

Critical self‐reflection for community practitioners | 8 domains for self‐reflection | – |

| Potential Partner Interview Guide 66 |

|

|

Assessment of community organization and their interest in partnering | 6 open‐ended questions | – |

| Community Health Initiative Interview Guide 58 |

|

|

Community assets assessment when initiating an academic‐community partnership |

107 open‐ended questions | Interview guide refined and revised through community partner input and interviewing role‐play |

| Selected Context and Process Measures | |||||

| Partnerships in Social Determinants of Health Interview Guide 45 |

|

|

Evaluation of academic‐community partnership processes Targeting SDH |

8 open‐ended questions | – |

| Partnership Assessment in Community‐based Research (PAIR) 43 |

|

|

Evaluation of critical elements of academic‐community partnership | 31 Likert‐type items and one open‐ended question | Community input sought at each step of measure development (generation of dimensions and items, item sorting and feedback, cognitive interviews and measure piloting) |

| Patient Engagement Workbook 49 |

|

|

Reflection guide for researchers considering engaging patients and documenting patient efforts | 102 open‐ended questions | – |

| Selected Measures of Context, Process, and Outcome | |||||

| Research for Improved Health (RIH) Partnership Interview Guide 85 |

|

|

To describe the challenges and successes of the participatory process and outcomes that arose from the partnership | 39 open‐ended questions | Developed and refined with relevant stakeholders |

| Rochester Suicide Prevention Training Institutes Evaluation 51 |

|

|

Follow‐up survey to assess knowledge and skills for engagement, partnership processes, and benefits or outcomes | 58 closed‐ended items (Likert, yes/no, checklist) |

Cronbach's α Personal knowledge = 0.55‐0.87 Partnership agency = 0.66‐0.93 Partnership benefits = 0.84‐0.92 |

| Program for the Elimination of Cancer Disparities (PECaD) Collaboration Survey 52 |

|

|

Assessing capacity, group dynamics, and effectiveness of achieving principles of CBPR in partnership | 45‐60 closed‐ and open‐ended items (adaptation by two different community‐engaged project groups results in a varying number of items) | – |

| CBPR Model Visioning Guide 82 |

|

|

Guidance for adapting a CBPR model to fit context, planning a new research project, evaluating partnership practices, and assessing the impact of practices |

19‐page workbook/ facilitation guide |

– |

| CBPR Model Visioning Guide 82 (cont.) |

|

|

– | ||

| Engage for Equity (E2) Key Informant Survey 99 |

|

|

To describe engaged project structural features and processes | 90 closed‐ and open‐ended items | Developed and refined through input with relevant stakeholders |

| Engage for Equity (E2) Community Engaged Research Survey 60 |

|

|

Assessment of context, partnership processes, and research processes of engaged project Evaluation of intermediate and long‐term outcomes of engaged research |

126 Likert‐type, yes/no, and open‐ended items | Refined through discussion with relevant stakeholders and psychometric testing 91 |

| Engage for Equity (E2) Community Engaged Research Survey 60 (cont.) |

|

|

|||

| Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Engagement Survey 76 |

|

|

Survey of academic perspectives on community engagement activities within clinical and translational science institutions | 12 yes/no or forced‐choice items | – |

| Partnership River of Life 59 |

|

|

To facilitate partnership reflection on the history and influences of the members and the goals, processes, and results of partnership | Group exercise and 5 open‐ended questions for reflection | – |

| Selected Process Measures | |||||

| Research for Improved Health (RIH) Focus Group Interview Guide 100 |

|

|

To understand participant experiences within an academic‐community partnership | 9 open‐ended questions | – |

| Partnership Trust Tool 69 |

|

|

Facilitate discussion about and enhance trust within the partnership |

58 items: 30 Likert‐type items and 28 open‐ended written questions |

– |

| Building Your Capacity Evaluation Survey 101 |

|

|

Assessment of community partner's research competencies post training | 14 Likert‐type items | – |

| Community Engagement in Research Index 46 |

|

|

Assessment of community partner's level of participation in various research tasks during engaged project | 12 closed‐ended items | Developed through qualitative interviews with community‐engaged project primary investigators |

| Youth‐Led Participatory Action Research (YPAR) Process Template 70 |

|

|

Classroom observational measure to assess the quality of YPAR implementation | 25 qualitative codes |

Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for interrater reliability: Training = 0.88 Promoting = 0.73 Group work = 0.97 Opportunities = 0.73 Communication = 0.76 Power over decisions = 0.66 Power over structure = 0.72 |

| Selected Process and Outcome Measures | |||||

| Participatory Evaluation Measure 102 |

|

|

To assess participatory evaluation practices | 3 coding schemes and weights | Face validity and apparent content validity, according to the authors |

| Participatory Impact Pathways Analysis 103 |

|

|

To allow researchers and stakeholders to jointly describe a project's “theories of action,” develop logic models, and use them for project planning and evaluation | 4 stages of impact planning | – |

| Interorganizational Network Survey (ION) 75 |

|

|

Change in community capacity over the past 12 months | 4 Likert‐type items and qualitative descriptions of linkages and resources | – |

| WeValueToolkit and List of Indicators 94 |

|

|

Assess intangible, values‐related processes and outcomes of organization's projects and activities | 166 indicators | Evaluated via field trials 104 |

| Community‐Based Participatory Research Rating Scale 71 |

|

|

To assess the perceived importance of CBPR factors to the current study | 33 Likert‐type items | Based on relevant social psychological and community organizing theory |

| Community Engagement Measure 65 |

|

|

Assessment of the quality and quantity of adherence to engagement principles |

48 Likert‐type items |

Cronbach's α Quality = 0.99 Quantity = 0.98 |

| Peer Engagement Process Evaluation Framework 105 |

|

|

To guide evaluation of primary data and project documents | 4 domains, with assessment questions and sample constructs to measure | – |

| Ripple Effect Tool 83 |

|

|

To measure increased social connectedness and other benefits of community‐engaged research participation | 12 open‐ended questions | – |

| Prevention Research Centers Cost Analysis Instrument 106 |

|

|

To systematically collect budget year data on the costs related to a community‐engaged project | 4 open‐ended items | Piloted with relevant stakeholders |

| Selected Outcome Measures | |||||

| Student Learning Outcomes of Community‐Based Research (CBR) 107 |

|

|

To measure student outcomes/benefits of participation in community‐based research coursework/projects | 19 yes/no and Likert‐type items |

Cronbach's α Overall CBR outcomes = 0.95 Professional skills = 0.91 Civic engagement = 0.86 Educational experience = 0.87 Academic skills = 0.80 Personal growth = 0.94. Convergent validity also tested |

| Social Network Analysis of Partnership Networks 108 |

|

|

Measure the evolution/change in interorganizational relationships | 19 survey items | – |

| Progress of Collaborative Action 47 |

|

|

Measuring progress of partnership; intensity of change and strategy employed for change | Mixed methods coding scheme across 3 domains for partnership document review | 96% inter‐observer agreement among 2 independent coders |

| Community Health Council Outcomes 109 |

|

|

Evaluate the effect of community health council actions on local health systems and health status outcomes | 20 quantitative indicators with accompanying narrative (open‐ended) probes | Developed through qualitative document review and quantitative survey of relevant stakeholders. Stakeholder participation in analysis interpretation |

| Knowledge Ownership Social Network Analysis 74 |

|

|

Change in active involvement in knowledge creation | 1 item | – |

| Critical Outcomes of Research Engagement 110 |

|

|

To assess the desired outcomes of engaged research | 25 open‐ended questions | Developed through a workshop with patient partners |

Appendix Table 2.

Characteristics of Reviews (2009‐2018)

| Review Authors | Years Represented | Sample Description | Key Domains Represented | Major Discussion Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowen et al. 25 | 1973‐2014 |

|

|

|

| Brett et al. 26 | 1995‐2012 |

|

|

|

| Concannon et al. 40 | 2003‐2012 |

|

|

|

| Conklin, Morris, and Nolte 41 | 2000‐2010 |

|

|

|

| Esmail, Moore, and Rein 16 | 2005‐2013 |

|

|

|

| Jagosh et al. 39 | Through 2009 |

|

|

|

| Manafo et al. 111 | 2007‐2017 |

|

|

|

| Nitsch et al. 112 | Through July 2011 |

|

|

|

| Sandoval et al. 29 | 2002‐2008 |

|

|

|

| Shen et al. 113 | 2005‐2015 |

|

|

|

| Tapp et al. 114 | 2003‐2013 |

|

|

|

Supporting information

Supplemental Table 1. Measures of Community Engagement (Organized by Context, Process, or Outcome Evaluation based upon Study Authors’ Descriptions)

Funding/Support

Drs. Hamilton and Luger were partially supported during the conduct of this review by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veteran Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development, VA QUE 15–272 and VA SDR 10–012. Dr. True received support from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, South Central Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed the ICMJE form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No disclosures were reported.

References

- 1. Cargo M, Mercer SL. The value and challenges of participatory research: strengthening its practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:325‐350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abma TA, Broerse JE. Patient participation as dialogue: setting research agendas. Health Expect. 2010;13(2):160‐173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Israel B, Eng E, Schulz A, Parker E. Methods in Community‐Based Participatory Research for Health. 2nd ed San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holzer JK, Ellis L, Merritt MW. Why we need community engagement in medical research. J Investig Med. 2014;62(6):851‐855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Allen ML, Salsberg J, Knot M, et al. Engaging with communities, engaging with patients: amendment to the NAPCRG 1998 Policy Statement on Responsible Research With Communities. Fam Pract. 2017;34(3):313‐321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, Minkler M. On community‐based participatory research In: Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, Minkler M, eds. Community‐Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2017:3‐16. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cashman SB, Adeky S, Allen AJ, et al. The power and the promise: working with communities to analyze data, interpret findings, and get to outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1407‐1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Concannon TW, Meissner P, Grunbaum JA, et al. A new taxonomy for stakeholder engagement in patient‐centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):985‐991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mullins CD, Abdulhalim AM, Lavallee DC. Continuous patient engagement in comparative effectiveness research. JAMA. 2012;307(15):1587‐1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shippee ND, Domecq Garces JP, Prutsky Lopez GJ, et al. Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expect. 2015;18(5):1151‐1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Isler MR, Corbie‐Smith G. Practical steps to community engaged research: from inputs to outcomes. J Law Med Ethics. 2012;40(4):904‐914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community‐based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312‐323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Westfall JM, Fagnan LJ, Handley M, et al. Practice‐based research is community engagement. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(4):423‐427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community‐based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl. 1):S40‐46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Getrich CM, Sussman AL, Campbell‐Voytal K, et al. Cultivating a cycle of trust with diverse communities in practice‐based research: a report from PRIME Net. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(6):550‐558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: moving from theory to practice. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(2):133‐145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frank L, Forsythe L, Ellis L, et al. Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient‐centered outcomes research institute. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1033‐1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Forsythe LP, Ellis LE, Edmundson L, et al. Patient and stakeholder engagement in the PCORI pilot projects: description and lessons learned. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):13‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frerichs L, Kim M, Dave G, et al. Stakeholder perspectives on creating and maintaining trust in community‐academic research partnerships. Health Educ Behav. 2017;44(1):182‐191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Forsythe LP, Frank L, Walker KO, et al. Patient and clinician views on comparative effectiveness research and engagement in research. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(1):11‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greenhalgh T, Jackson C, Shaw S, Janamian T. Achieving research impact through co‐creation in community‐based health services: literature review and case study. Milbank Q. 2016;94(2):392‐429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schmittdiel JA, Grumbach K, Selby JV. System‐based participatory research in health care: an approach for sustainable translational research and quality improvement. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(3):256‐259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hardy LJ, Hughes A, Hulen E, Figueroa A, Evans C, Begay RC. Hiring the experts: best practices for community‐engaged research. Qual Res. 2016;16(5):592‐600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moreno G, Rodriguez MA, Lopez GA, Bholat MA, Dowling PT. Eight years of building community partnerships and trust: the UCLA family medicine community‐based participatory research experience. Acad Med. 2009;84(10):1426‐1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bowen DJ, Hyams T, Goodman M, West KM, Harris‐Wai J, Yu JH. Systematic review of quantitative measures of stakeholder engagement. Clin Trans Sci. 2017;10(5):314‐336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. A systematic review of the impact of patient and public involvement on service users, researchers and communities. Patient. 2014;7(4):387‐395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect. 2014;17(5):637‐650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mockford C, Staniszewska S, Griffiths F, Herron‐Marx S. The impact of patient and public involvement on UK NHS health care: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(1):28‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sandoval JA, Lucero J, Oetzel J, et al. Process and outcome constructs for evaluating community‐based participatory research projects: a matrix of existing measures. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(4):680‐690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chung B, Jones L, Jones A, et al. Using community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):237‐244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles In: Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, Minkler M, eds. Community‐Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. 3rd ed San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2017:31‐44. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eder MM, Carter‐Edwards L, Hurd TC, Rumala BB, Wallerstein N. A logic model for community engagement within the Clinical and Translational Science Awards consortium: can we measure what we model? Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1430‐1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Selby JV, Slutsky JR. Practicing partnered research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(Suppl 4):S814‐816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Frakt AB, Prentice JC, Pizer SD, et al. Overcoming challenges to evidence‐based policy development in a large, integrated delivery system. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(6):4789‐4807. Epub June 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miake‐Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, Shekelle PG. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Master journal list. Clarivate Analytics website. http://mjl.clarivate.com.ccl.idm.oclc.org/?ref=MasterJournalListWOS. Published 2019. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- 38. Academic Search Premier : at a glance. EBSCO website. https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/academic-search-premier. Published 2019. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- 39. Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Q. 2012;90(2):311‐346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T, et al. A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient‐centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(12):1692‐1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Conklin A, Morris Z, Nolte E. What is the evidence base for public involvement in health‐care policy? Results of a systematic scoping review. Health Expect. 2015;18(2):153‐165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tableau Public [computer program] . Seattle, WA. 2018.

- 43. Arora PG, Krumholz LS, Guerra T, Leff SS. Measuring community‐based participatory research partnerships: the initial development of an assessment instrument. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2015;9(4):549‐560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Heaton K, Smith GR, King K, et al. Community grand rounds: re‐engineering community and academic partnerships in health education—a partnership and programmatic evaluation. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2014;8(3):375‐385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Paradiso de Sayu R, Sparks SM. Factors that facilitate addressing social determinants of health throughout community‐based participatory research processes. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2017;11(2):119‐127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Khodyakov D, Stockdale S, Jones A, Mango J, Jones F, Lizaola E. On measuring community participation in research. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(3):346‐354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Collie‐Akers VL, Fawcett SB, Schultz JA. Measuring progress of collaborative action in a community health effort. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2013;34(6):422‐428. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Research for Improved Health Study Team . Research for Improved Health Community Engaged Research survey instrument. University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research website. https://cpr.unm.edu/research-projects/cbpr-project/research-for-improved-health.html. Published 2011. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- 49. Madrid S, Wright L. Patient Engagement Workbook. Madison, WI: HIPxChange; 2014. https://www.hipxchange.org/HCSRNEngagementWorkbook. Accessed May 15, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Morrow E, Ross F, Grocott P, Bennett J. A model and measure for quality service user involvement in health research. Int J Consum Stud. 2010;34(5):532‐539. [Google Scholar]

- 51. White AM, Lu N, Cerulli C, Tu X. Examining benefits of academic‐community research team training: Rochester's suicide prevention training institutes. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2014;8(1):125‐137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Arroyo‐Johnson C, Allen ML, Colditz GA, et al. A tale of two community networks program centers: operationalizing and assessing CBPR principles and evaluating partnership outcomes. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2015;9(Suppl.):61‐69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jewett‐Tennant J, Collins C, Matloub J, et al. Partnership among peers: lessons learned from the development of a community organization‐academic research training program. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2016;10(3):461‐470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Forsythe L, Heckert A, Margolis MK, Schrandt S, Frank L. Methods and impact of engagement in research, from theory to practice and back again: early findings from the Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(1):17‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Goytia CN, Todaro‐Rivera L, Brenner B, Shepard P, Piedras V, Horowitz C. Community capacity building: a collaborative approach to designing a training and education model. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2013;7(3):291‐299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement . Is research working for you? A self‐assessment tool and discussion guide for health services management and policy organizations. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement; 2014. https://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/PublicationsAndResources/ResourcesAndTools/SelfAssessmentTool.aspx. Accessed May 15, 2019 . [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rubin CL, Allukian N, Wang X, et al. “We make the path by walking it”: building an academic community partnership with Boston Chinatown. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2014;8(3):353‐363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gibbons MC, Illangasekare SL, Smith E, Kub J. A community health initiative: evaluation and early lessons learned. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2016;10(1):89‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sanchez‐Youngman S, Wallerstein N. Partnership River of Life: creating a historical time line In: Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, Minkler M, eds. Community‐Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. 3rd ed San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Engage for Equity Study Team. Engage for Equity Community Engaged Research survey University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research website. https://cpr.unm.edu/research-projects/cbpr-project/index.html. Published 2016. Accessed May 15, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 61. DiGirolamo A, Geller AC, Tendulkar SA, Patil P, Hacker K. Community‐based participatory research skills and training needs in a sample of academic researchers from a clinical and translational science center in the Northeast. Clin Trans Sci. 2012;5(3):301‐305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Salihu HM, Salinas‐Miranda AA, Wang W, Turner D, Berry EL, Zoorob R. Community Priority Index: utility, applicability and validation for priority setting in community‐based participatory research. J Public Health Res. 2015;4(2):443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bauermeister JA, Pingel ES, Sirdenis TK, Andrzejewski J, Gillard G, Harper GW. Ensuring community participation during program planning: lessons learned during the development of a HIV/STI program for young sexual and gender minorities. Am J Community Psy. 2017;60(1‐2):215‐228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Braun KL, Nguyen TT, Tanjasiri SP, et al. Operationalization of community‐based participatory research principles: assessment of the National Cancer Institute's community network programs. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(6):1195‐1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Goodman MS, Sanders Thompson VL, Johnson CA, et al. Evaluating community engagement in research: quantitative measure development. J Community Psy. 2017;45(1):17‐32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Orellano‐Colon EM, Gonzalez‐Laboy Y, De Jesus‐Rosario A. Creation of the Quebrada Arriba community and academic partnership: an effective coalition for addressing health disparities in older Puerto Ricans. P R Health Sci J. 2017;36(2):107‐114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Paige C, Peters R, Parkhurst M, et al. Enhancing community‐based participatory research partnerships through appreciative inquiry. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2015;9(3):457‐463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Lantz P. Instrument for evaluating dimensions of group dynamics within community‐based participatory research partnerships. Eval Program Plann. 2003;26(3):249‐262. [Google Scholar]

- 69. CDC Prevention Research Centers . Partnership Trust Tool survey. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. https://www.cdc.gov/prc/pdf/pptusersmanual.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ozer EJ, Douglas L. Assessing the key processes of youth‐led participatory research. Youth Soc. 2015;47(1):29‐50. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pivik JR, Goelman H. Evaluation of a community‐based participatory research consortium from the perspective of academics and community service providers focused on child health and well‐being. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38(3):271‐281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Oetzel JG, Villegas M, Zenone H, White Hat ER, Wallerstein N, Duran B. Enhancing stewardship of community‐engaged research through governance. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):1161‐1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sharpe PA, Flint S, Burroughs‐Girardi EL, Pekuri L, Wilcox S, Forthofer M. Building capacity in disadvantaged communities: development of the community advocacy and leadership program. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2015;9(1):113‐127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Salsberg J, Macridis S, Garcia Bengoechea E, Macaulay AC, Moore S. The shifting dynamics of social roles and project ownership over the lifecycle of a community‐based participatory research project. Fam Pract. 2017;34(3):305‐312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wendel ML, Prochaska JD, Clark HR, Sackett S, Perkins K. Interorganizational network changes among health organizations in the Brazos Valley, Texas. J Prim Prev. 2010;31(1‐2):59‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Eder MM, Evans E, Funes M, et al. Defining and measuring community engagement and community‐engaged research: clinical and translational science institutional practices. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2018;12(2):145‐156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Balls‐Berry JE, Sinicrope PS, Valdez Soto MA, et al. Using garden cafes to engage community stakeholders in health research. PloS One. 2018;13(8):e0200483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Coombe CM, Schulz AJ, Guluma L, et al. Enhancing capacity of community‐academic partnerships to achieve health equity: results from the CBPR Partnership Academy. Health Promot Pract. 2018:1524839918818830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Eaton AD, Ibáñez‐Carrasco F, Craig SL, et al. A blended learning curriculum for training peer researchers to conduct community‐based participatory research. Action Learning: Research and Practice. 2018;15(2):139‐150. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ward M, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Rice K, Martenies SE, Markarian E. A conceptual framework for evaluating health equity promotion within community‐based participatory research partnerships. Eval Program Plann. 2018;70:25‐34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Research for Improved Health Study Team . Research for Improved Health key informant survey. University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center website. https://cpr.unm.edu/research-projects/cbpr-project/research-for-improved-health.html. Published 2011. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- 82. Engage for Equity Study Team . CBPR Visioning Guide. University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research website. https://cpr.unm.edu/research-projects/cbpr-project/facilitation_tools.html. Published 2016. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- 83. Hardy LJ, Hulen E, Shaw K, Mundell L, Evans C. Ripple effect: an evaluation tool for increasing connectedness through community health partnerships. Action Res (Lond). 2017;16(3):299‐318. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hardy LJ, Wertheim P, Bohan K, Quezada JC, Henley E. A model for evaluating the activities of a coalition‐based policy action group: the case of Hermosa Vida. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(4):514‐523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Research for Improved Health Study Team . Research for Improved Health partnership interview guide. University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research website. https://cpr.unm.edu/research-projects/cbpr-project/research-for-improved-health.html. Published 2011. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- 86. Khodyakov D, Mikesell L, Schraiber R, Booth M, Bromley E. On using ethical principles of community‐engaged research in translational science. Transl Res. 2016;171:52‐62 e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Sprague Martinez L, Reisner E, Campbell M, Brugge D. Participatory democracy, community organizing and the Community Assessment of Freeway Exposure and Health (CAFEH) partnership. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. True G, Davidson L, Facundo R, Meyer DV, Urbina S, Ono SS. “Institutions don't hug people”: a roadmap for building trust, connectedness, and purpose through photovoice collaboration. J Humanist Psychol. 2019:1‐40. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Deverka PA, Lavallee DC, Desai PJ, et al. Stakeholder participation in comparative effectiveness research: defining a framework for effective engagement. J Comp Eff Res. 2012;1(2):181‐194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, Rae R. What predicts outcomes in CBPR In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, eds. Community‐Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Oetzel JG, Wallerstein N, Duran B, et al. Impact of participatory health research: a test of the community‐based participatory research conceptual model. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:7281405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Andrews JO, Cox MJ, Newman SD, Meadows O. Development and evaluation of a toolkit to assess partnership readiness for community‐based participatory research. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2011;5(2):183‐188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Southerland J, Behringer B, Slawson DL. Using the give‐get grid to understand potential expectations of engagement in a community‐academic partnership. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(6):909‐917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. University of Brighton . Understanding and evaluating intangible impacts of projects and organisations. WeValue website. http://blogs.brighton.ac.uk/wevalue/. Published 2015. Accessed March 1, 2019.

- 95. Kothari A, MacLean L, Edwards N, Hobbs A. Indicators at the interface: managing policymaker‐researcher collaboration. Knowledge Management Research & Practice. 2011;9(3):203‐214. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Harris J, Cook T, Gibbs L, et al. Searching for the impact of participation in health and health research: challenges and methods. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9427452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Vaughn LM, Lohmueller M. Calling all stakeholders: group‐level assessment (GLA)—a qualitative and participatory method for large groups. Eval Rev. 2014;38(4):336‐355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hyde C. Challenging ourselves: critical self‐reflection on power and privilege In: Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, Minkler M, eds. Community‐Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity. 3rd ed San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2017:337‐344. [Google Scholar]

- 99. Engage for Equity Study Team . Engage for Equity key informant survey. University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research website. https://cpr.unm.edu/research-projects/cbpr-project/index.html. Published 2016. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- 100. Research for Improved Health Study Team . Research for Improved Health focus group guide. University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research website. https://cpr.unm.edu/research-projects/cbpr-project/research-for-improved-health.html. Published 2011. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- 101. Rubin CL, Martinez LS, Chu J, et al. Community‐engaged pedagogy: a strengths‐based approach to involving diverse stakeholders in research partnerships. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(4):481‐490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Daigneault P‐M, Jacob S. Toward accurate measurement of participation. Am J Eval. 2009;30(3):330‐348. [Google Scholar]

- 103. Alvarez S, Douthwaite B, Thiele G, Mackay R, Córdoba D, Tehelen K. Participatory Impact Pathways Analysis: a practical method for project planning and evaluation. Dev Pract. 2010;20(8):946‐958. [Google Scholar]

- 104. Burford G, Velasco I, Janouskova S, et al. Field trials of a novel toolkit for evaluating “intangible” values‐related dimensions of projects. Eval Program Plann. 2013;36(1):1‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Greer AM, Luchenski SA, Amlani AA, Lacroix K, Burmeister C, Buxton JA. Peer engagement in harm reduction strategies and services: a critical case study and evaluation framework from British Columbia, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Rabarison KM, Marcelin RA, Bish CL, Chandra G, Massoudi MS, Greenlund KJ. Cost analysis of prevention research centers: instrument development. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(5):440‐443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Lichtenstein G, Thorme T, Cutforth N, Tombari ML. Development of a national survey to assess student learning outcomes of community‐based research. J High Educ Outreach Engagem. 2011;15(2):7‐33. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Luque JS, Tyson DM, Bynum SA, et al. A social network analysis approach to understand changes in a cancer disparities community partnership network. Ann Anthropol Pract. 2011;35(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Andrews ML, Sanchez V, Carrillo C, Allen‐Ananins B, Cruz YB. Using a participatory evaluation design to create an online data collection and monitoring system for New Mexico's community health councils. Eval Program Plann. 2014;42:32‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Dillon EC, Tuzzio L, Madrid S, Olden H, Greenlee RT. Measuring the impact of patient‐engaged research: how a methods workshop identified critical outcomes of research engagement. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2017;4(4):237‐246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Manafo E, Petermann L, Vandall‐Walker V, Mason‐Lai P. Patient and public engagement in priority setting: a systematic rapid review of the literature. PloS One. 2018;13(3):e0193579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Nitsch M, Waldherr K, Denk E, Griebler U, Marent B, Forster R. Participation by different stakeholders in participatory evaluation of health promotion: a literature review. Eval Program Plann. 2013;40:42‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Shen S, Doyle‐Thomas KAR, Beesley L, et al. How and why should we engage parents as co‐researchers in health research? A scoping review of current practices. Health Expect. 2017;20(4):543‐554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Tapp H, White L, Steurerwald M, Dulin M. Use of community‐based participatory research in primary care to improve healthcare outcomes and disparities in care. J Comp Eff Res. 2013;2(4):405‐419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Kothari A, Edwards N, Hamel N, Judd M. Is research working for you? Validating a tool to examine the capacity of health organizations to use research. Implement Sci. 2009;4:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Maar M, Yeates K, Barron M, et al. I‐RREACH: an engagement and assessment tool for improving implementation readiness of researchers, organizations and communities in complex interventions. Implement Sci. 2015;10:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Barbieri N, Gallego R, Morales E, Rodríguez‐Sanz M, Palència L, Pasarín MI. Measuring and analysing community action for health: an indicator‐based typology and its application to the case of Barcelona. Soc Indic Res. 2017;139(1):25‐45. [Google Scholar]

- 118. Tagai EK, Scheirer MA, Santos SLZ, et al. Assessing capacity of faith‐based organizations for health promotion activities. Health Promot Pract. 2018;19(5):714‐723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Oetzel JG, Zhou C, Duran B, et al. Establishing the psychometric properties of constructs in a community‐based participatory research conceptual model. Am J Health Promot. 2015;29(5):e188‐202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Tremblay MC, Martin DH, Macaulay AC, Pluye P. Can we build on social movement theories to develop and improve community‐based participatory research? A framework synthesis review. Am J Community Psy. 2017;59(3‐4):333‐362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Ozer EJ, Schotland M. Psychological empowerment among urban youth: measure development and relationship to psychosocial functioning. Health Educ Behav. 2011;38(4):348‐356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]