Abstract

Policy Points.

An onslaught of policies from the federal government, states, the insurance industry, and professional organizations continually requires primary care practices to make substantial changes; however, ineffective leadership at the practice level can impede the dissemination and scale‐up of these policies.

The inability of primary care practice leadership to respond to ongoing policy demands has resulted in moral distress and clinician burnout.

Investments are needed to develop interventions and educational opportunities that target a broad array of leadership attributes.

Context

Over the past several decades, health care in the United States has undergone substantial and rapid change. At the heart of this change is an assumption that a more robust primary care infrastructure helps achieve the quadruple aim of improved care, better patient experience, reduced cost, and improved work life of health care providers. Practice‐level leadership is essential to succeed in this rapidly changing environment. Complex adaptive systems theory offers a lens for understanding important leadership attributes.

Methods

A review of the literature on leadership from a complex adaptive system perspective identified nine leadership attributes hypothesized to support practice change: motivating others to engage in change, managing abuse of power and social influence, assuring psychological safety, enhancing communication and information sharing, generating a learning organization, instilling a collective mind, cultivating teamwork, fostering emergent leaders, and encouraging boundary spanning. Through a secondary qualitative analysis, we applied these attributes to nine practices ranking high on both a practice learning and leadership scale from the Learning from Effective Ambulatory Practice (LEAP) project to see if and how these attributes manifest in high‐performing innovative practices.

Findings

We found all nine attributes identified from the literature were evident and seemed important during a time of change and innovation. We identified two additional attributes—anticipating the future and developing formal processes—that we found to be important. Complexity science suggests a hypothesized developmental model in which some attributes are foundational and necessary for the emergence of others.

Conclusions

Successful primary care practices exhibit a diversity of strong local leadership attributes. To meet the realities of a rapidly changing health care environment, training of current and future primary care leaders needs to be more comprehensive and move beyond motivating others and developing effective teams.

Keywords: leadership, primary care, complex adaptive system theory, qualitative research

For the past two decades, primary care in the united States has been in a period of transition, with considerable external pressure from payers, policymakers, and the public to improve quality and reduce costs. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Additional pressures for transformation come from within the ranks of primary care itself, as professional organizations seek new models of practice such as the patient‐centered medical home (PCMH), 7 , 8 and even newer models as more is learned about the strengths and limitations of the PCMH model, 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 and as efforts are made toward payment reform and achieving the quadruple aim of enhancing patient experience, improving population health, reducing cost, and improving the work life of health care providers and thus reduced physician burnout. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 Nevertheless, transforming primary care practice in the current health care environment is challenging 17 , 18 and, among other things, requires leadership skills at the practice level for facilitating successful and sustainable change. 19 , 20 , 21

Engaged leadership has been identified as a key “change concept” for successful PCMH implementation by the Safety Net Medical Home Initiative, 22 , 23 and it is one of the ten building blocks of high‐performing primary care. 24 Nevertheless, little empirical research has looked at what comprises effective leadership or how leadership is cultivated and supported in primary care settings. Some recent research from Europe, however, examines leadership training. A recent focus group study in Norway found that while general practitioners recognized the need to take on leadership roles, they did not have the leadership skills and training needed to effectively lead their teams. 25 A survey of primary care professionals in Scotland found fewer than half had previous leadership training, and among nurses, less than 30% had such training. 26 Nevertheless, there are documented examples of primary care practices that do have engaged leaders who have successfully transitioned practices into advanced PCMH models despite challenges. 20 , 27 , 28

Over the past 30 years, two of the authors (WLM and BFC) actively engaged in a program of research that included hundreds of primary care practices. 17 , 18 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 As we studied practices, we observed that they generally did not follow linear patterns of change, often changing in unanticipated ways. This led us to discover a large literature on complexity science and its application to leadership, 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 and thus to explore and integrate models based on complex adaptive system theory into our research. 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 That is, complexity science theory helped us to see primary care practices as dynamic systems in which interactions and relationships of different components and agents (including leaders) simultaneously affect and are shaped by the system. 44 In an early practice change model, we recognized leadership as a critical resource for change; 47 however, it was not until we applied this model in a large intervention study that we saw the absolutely critical role of practice leadership, or lack thereof, in facilitating or inhibiting change processes. In the Using Learning Teams for Reflective Adaptation (ULTRA) study, 29 we noted that the primary care practices that were minimally engaged in participation had disengaged leaders or poor communication between the leaders and others in the practice. 48 , 49 , 50 This knowledge was reinforced in subsequent studies in which intervention outcomes did not meet expectations. 18 , 51 , 52 We felt that for practice change efforts to be successful there needed to be more leadership training and so began a review of the literature on leadership from a complexity science lens during times of change.

In collaboration with Reuben R. McDaniel Jr. from the University of Texas at Austin, one of the authors (BFC) began reviewing the complexity science literature on leadership to help us understand and describe what we were seeing in the ULTRA practices. We met biweekly to review and discuss articles over an 11‐month period, beginning with reading McDaniel's article on strategic leadership, 38 followed by publications by Karl Weick 53 , 54 , 55 and Amy Edmundson. 56 , 57 The focus of much of these early publications was on the role of relationships, communication, and psychological safety in organizations. This led to a deeper exploration of the literature on power, beginning with the classic French and Raven 58 and subsequent early publications on the role of power in relationships and leadership. 59 , 60 Throughout these meetings we kept detailed notes on the concepts that became the start of a loose codebook. Over time, we considered what concepts to keep in mind as we went back to the ULTRA practice data and applied the concepts to our earlier practice change model. 47

In the literature we reviewed, which included business, management, and health care fields, there were articles about attributes and characteristics of good leaders and good leadership in organizations, but little about leaders or leadership in primary care. Therefore, in the analysis used in this article, we define leaders and leadership based on the broader literature, not specifically relating to the primary care setting. We define leaders as those individuals who (1) hold formal or legitimate leadership titles or positions within the organization, and (2) have financial control (financial power) over the practice. 53 , 58 , 61 We define leadership as the enactment of actions, behaviors, or attitudes that influence the policies and procedures, mission and vision, and process tools (such as communications and information sharing) that shape the direction of the organization. 56 , 62

This literature highlights attributes of both individual leaders and leadership. Although there is no firm agreement on all the attributes, or even the relative contribution of specific attributes for success, there are a number of leader and leadership characteristics generally considered to be important. Using a complexity lens in our reading of this literature, we identified nine leadership attributes that are referred to with some consistency. Although many of these are overlapping concepts, the literature has treated them separately. Our investigation is a secondary data analysis from the Learning from Effective Ambulatory Practices (LEAP) project, a large descriptive study of innovative primary care practices. 16 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 We first review and summarize the nine leadership attributes and then examine how they manifest in nine primary care practices purposefully selected from practices with national reputations as workforce innovators.

Nine Leadership Attributes

The literature on leadership from a complex adaptive system perspective is replete with theories of and studies about organizational change, which include the widely recognized leadership attribute of motivating the workforce to engage in system change efforts. 38 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 Leaders motivating others to engage in change encompasses two fundamentally different approaches to motivation: motivating through reinforcement and reward (transactional leadership) or through facilitating an environment that maximizes internal motivation (transformational leadership). Although a transactional style can be effective in some contexts, it is recognized to not be ideal in innovative and rapidly changing contexts. 71 Much literature is devoted to identifying specific leadership skills and behaviors that characterize a more transformational approach to motivation, including prioritizing abundant communication and facilitating a work environment that encourages a sense of autonomy, mastery, and purpose. 72 , 73

Within health care organizations, there is considerable differentiation in the power and social influence of some individuals relative to others, making managing abuse of power and social influence an important leadership attribute. 58 , 60 , 74 Often the locus of power involves physicians (particularly when they are practice owners) and the office manager. Physician leaders tend to underestimate the perception of their power among staff and often act in ways that demonstrate the power differential rather than mitigating it. 35 In their seminal work, Raven and French describe social power theory in organizations. 58 , 60 Raven later summarizes this work, noting that social influence is a change in the belief, attitude, or behavior of a target person by an influencing agent, with social power being “the potential for such influence.” 59 He introduces the “power/interaction model of interpersonal influence” and different strategies power holders (agents) use with subordinates (targets). Georgesen and Harris define power as “the amount of unshared control possessed by one member of a dyad over the other member” and link their work to French and Raven's conceptualizations of reward and coercive types of power because they involve asymmetrical relationships. 74 However, high interpersonal control is not inherently damaging to relationships; in some circumstances it may facilitate leadership behaviors if the leader has awareness of the agent/target relationship and/or “empowerment” needed to improve work outcomes. 75 , 76 Leadership must be intolerant of behaviors such as bullying, freeloading, and cheating. 77

Depending on how power differences are managed, those with less power may or may not feel psychologically safe to express opinions or contribute ideas. Assuring psychological safety has been shown to contribute to or inhibit problem solving and giving input. 56 , 57 , 78 Effective leaders create psychologically safe environments whereby employees can respond in the moment (first‐order problem solving) while addressing system failure later (second‐order problem solving). 57 Power differences can intensify interpersonal risk; the interpersonally safe route is to remain silent, but it poses a technical risk if the context calls for learning. 56 , 79 Nevertheless, employees lower on the hierarchy tend to have richer data on actions; “they are at the sharp end of the chain of adversity” and can be torn between justification and candor. 55 Professional status is positively associated with psychological safety; when people feel safe, they speak up and learn, and a leader's inclusive behavior predicts psychological safety. 78

Instilling a collective mind is described by Weick and Roberts as a pattern of heedful interrelations whereby individuals in a social system understand that their actions are interconnected and create group cohesion by observing the ways their actions (contributions) connect and interrelate within a system to form a collective mind. 54 As such, Uhl‐Bien and Graen see this as the transformation of a group of individuals on a team into a cohesive unit that places team interests above their own individual self‐interests. 41 For example, a primary care practice can regularly use huddles, meetings, and retreats to increase understanding of collective goals of the practice. This also increases the practice's sensemaking skills. 54 , 80 Thus, leadership attends to patterns of heedful interrelations whereby individuals recognize interconnectedness and cocreate group cohesion and a shared purpose.

Teamwork is an increasingly common feature of modern health care organizations, and consequently, the need for cultivating teamwork is well studied. 81 , 82 This is different from collective mind in that cultivating teamwork is about how to get a group of people to effectively work on a set of tasks, while instilling a collective mind focuses on getting teams and individuals in a practice to have a common purpose and understanding. In the larger literature on teamwork, Uhl‐Bien and Graen distinguish between traditional management and team leadership: the former typically has been about controlling routine and ensuring compliance, while the latter involves investing in relationships, continuous organizational improvement, and creating the conditions for “transforming self‐interest into team‐interest.” 41 Others have also emphasized the role of the leader as cultivating conditions that enable the team to thrive, rather than micromanaging the team. 83 One such condition commonly found to be important is cultivating a “shared mind‐set” or “shared consciousness,” which allows for a coordination of efforts and an understanding of one's part within the larger whole. 84 , 85 McChrystal summarizes the role of leadership in nurturing teamwork: “Instead of seeing an organization as a ‘machine’ where you only need a leader to plug in the right inputs, organizations need to be seen as a ‘living organism’ that needs a certain type of environment to grow and evolve. The role of today's leaders is to foster that environment.” 85

Enhancing communication and information sharing is an important attribute for effective leadership, including using a combination of rich (eg, face‐to‐face) and lean (eg, email, memos) communication, formal and informal forums, and both written and verbal formats. The literature suggests that leaders on all levels need to communicate “big‐picture” goals and vision. 62 , 86 Daft and Lengel, focusing on different types of communication, describe how communications can be used to change understanding and clarify ambiguity. 87 Nevertheless, there are more often descriptions of the barriers to communication or moments where employees make decisions not to communicate due to a sense of personal risk, perception that their comments are not valued, or other instances where hierarchy and status differences have a silencing effect on information exchange. 56 , 76 It is important that leadership undertakes and manages multiple forms of communication and information sharing related to the workplace.

The concept of a learning organization emerged from Peter Senge's work, in which he describes people working together in generating a learning organization by enhancing their capacities and continually transforming the organization. 88 Many learning organization concepts have been adapted into health care, particularly by Amy Edmondson. 56 , 57 Essential factors for organizational learning include a supportive learning environment, concrete learning processes, and leadership behaviors to reinforce continual reflection and learning. 89 , 90 Embedded within these factors are other leadership attributes such as psychological safety and having formal processes. “A learning organization is an organization skilled at creating, acquiring, and transferring knowledge, and at modifying behavior to reflect new knowledge and insights.” 89 Edmondson, Bohmer, and Pisano describe the learning process whereby organizations make cognitive, interpersonal, and organizational adjustments that allow new routines to be successfully implemented. 91

Another widely recognized leadership attribute is encouraging boundary spanning, or reaching across established borders to build relationships, gain information and resources, and form productive connections. 56 , 92 , 93 , 94 In the business literature, boundary spanning is considered an essential attribute for top‐level and middle managers, as it can help companies innovate and achieve a competitive advantage. 95 Burt describes individuals who are able to reach outside their homogeneous work groups to connect and aid the flow of information among groups, as “fillers of structural holes,” another term for boundary spanners. 93 While boundary spanning refers to the border crossings that leaders themselves perform, an additional attribute describes leaders’ support for their workforce to cross boundaries of traditional roles. Workforce flexibility has been described as an attempt to “break down the boundaries that reduce the ability of the health workforce to respond to population needs.” 96 Encouraging workforce flexibility has been shown to be associated with organizational efficiency and capacity for change in a health care context. 97 Vertical boundary spanning that cuts across levels and hierarchy (eg, physicians versus nurses), horizontal boundary spanning (eg, across functions and expertise), and stakeholder boundary spanning (eg, beyond the organization to include the larger medical neighborhood) are particularly evident at the practice level. 94

Fostering emergent leadership involves leadership creating dynamic interactions that lead to the emergence of new leadership as system members resolve problems or tension. 98 The notion of distributed leadership can be used to describe leadership emerging at different times based on the needs of the moment. 99 , 100 In a study of adopting an integrated delivery system, leadership came from lower in the organization, but senior management backed these new leaders by giving a strategic perspective that they did not have. 101 Uhl‐Bien and Graen describe how project managers emerge as leaders by earning respect from the team; leadership in these instances entails communication and coordination in order to gain incremental influence. 41 Kouzes and Posner see leadership as a possibility for everyone and is an action‐oriented process that arises out of relationships. 102 Leadership facilitates dynamic interaction through skill development, distributing the responsibility, and improving improvisational skills within the workforce so members can emerge for problem solving or moments requiring leadership action.

Methods

This is a comparative case study of leadership attributes in high‐performing primary care practices, using secondary qualitative data from the Primary Care Team: Learning from Effective Ambulatory Practices (PCT‐LEAP) study. The goal of the analysis was to see if and how leadership attributes manifest in high‐performing practices.

Study Design

In this study, we used a comparative case study design of nine purposefully selected primary care practices with reputations and evidence of being particularly innovative and successful. 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 103 These practices were selected as a contrast to the growing literature noting a lack of effective leadership in practices, which inhibits successful change. 21 , 104 This literature serves as a comparator group to the nine practices used in this study.

The nine practices were part of a national program created by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Primary Care Team: Learning from Effective Ambulatory Practices (PCT‐LEAP), devoted to helping primary care practices use insights from the study of innovative, high‐performing practices. To select practices, we identified primary care thought leaders from a comprehensive literature review of primary care workforce innovations, 103 then individually contacted them to recommend practice innovators, eventually recommending 227 potentially relevant practices that subsequently completed a 45‐minute telephone interview. We summarized notes from interviews into two‐page structured reports for 154 practices deemed to have workforce innovations. The National Advisory Committee for the PCT‐LEAP national program discussed each of the 154 practices at length and ultimately selected 30 practices as being especially innovative, as evidenced in the descriptions described later in this paper. Selected practices included a range of geographic locations/settings, practice organizational types, and populations served. More details are available in earlier publications 64 , 65 , 66 and on the internet at www.improvingprimarycare.org/start/about.

Data Collection

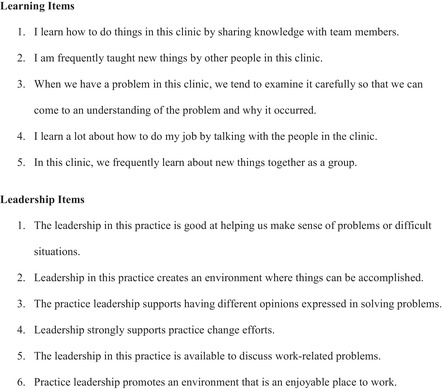

Each of the 30 PCT‐LEAP practice sites hosted a three‐day site visit between August 2012 and September 2013 by a team of three to five people that included a clinician investigator, a qualitative researcher, and a research assistant. 65 , 66 Data collection during site visits included direct observation of practice activities, team meetings, and patient visits, as well as audio‐recorded formal semistructured interviews and informal key informant interviews with practice leaders, clinicians, and staff. Site visit teams captured observations and key informant interviews in written fieldnotes, and audio‐recorded interviews were transcribed. In addition, staff members at each practice completed a short structured survey that included specific items related to practice learning and leadership. The five learning items were the reciprocal learning subscale identified by Leykum and colleagues from the larger Assessment of Chronic Illness Care scale and were designed to measure the processes where people learn from sharing with others. 105 The six‐item leadership scale included items from the adaptive reserve instrument used in the PCMH National Demonstration Project 106 as well as items on inclusive leadership. 107

To identify the LEAP practices most likely to exemplify the best leadership qualities, we used results from the two structured surveys (Figure 1). We separately ranked the 30 LEAP practices on both the five learning scale items and the six leadership scale items. We selected the nine practices that ranked in the top ten on both scales for this secondary qualitative analysis. Overall among the 30 LEAP practices, the mean scores for the learning items ranged from a high of 4.59 (SD = 0.39) to a low of 3.67 (SD = 0.61), while the leadership items ranged from a high of 4.56 (SD = 0.45) to a low of 3.32 (SD = 0.84). When we sorted the practices on the two scales, there was remarkable consistency between both scales, with nine practices being in the top ten on both. These nine practices had mean scores of 4.12 or greater on the learning items and 4.07 or greater on the leadership items.

Figure 1.

Learning and Leadership Items Rated on a 5‐Point Scale From Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree

Data Analysis

We used a two‐step process for coding and analyzing the nine practices selected from the LEAP data set. We initially coded all 30 LEAP practices in Atlas.ti on 18 broad codes that included leadership. Three members of the LEAP team conducted this initial coding. We then coded all text output from the leadership code for the nine practices with a more detailed codebook that targeted specific leadership attributes (Table 1). These codes focused on the nine leadership attributes derived from the literature as described in the introduction. It became apparent, however, that we needed some additional codes. For example, these practices established multiple formal processes for managing information both vertically and horizontally. Formal processes occurred at different levels and included quality improvement approaches such as the use of total quality management (TQM), Six Sigma, and Lean; as well as activities like performance management, hiring and training, policy and procedures, and formal meeting structures and templates such as huddles. 108 In addition, we quickly discovered these innovative practices were consistently looking ahead and working to position themselves for future success in a rapidly changing landscape. Thus, we created emergent codes developing formal processes and anticipating the future and added them to the codebook for a total of 11 attributes.

Table 1.

Practice Ratings of Attributes With Definitionsa

| Practice ID | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership Attribute | Definition | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Motivating others to engage in change | Leadership engages workforce when system change occurs or needs to occur and provides motivation and encouragement to support system change efforts through external/extrinsic motivation (transactional leadership) and internal/intrinsic motivation (transformational leadership), while also overcoming resistance. | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Managing abuse of power and social influence | Leadership addresses issues of power and social influence within and among the workforce, including issues like bullying, freeloading, and cheating, and seeks mutual respect and fairness across hierarchy. | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Assuring psychological safety | Leadership assures that the work environment is one in which everyone can express opinions or contribute to discussions without fear such that practice members speak up with suggestions, questions, and criticisms of work‐related processes. | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Enhancing communication and information sharing | Leadership undertakes and manages the multiple forms of internal and external communication and information sharing related to the workplace. Communication occurs in various forms, from formal meetings to informal exchanges connecting people, and using both written and verbal information as appropriate. | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 |

| Generating a learning organization | Leadership helps to generate an organization that is “skilled at creating, acquiring, and transferring knowledge, and at modifying its behavior to reflect new knowledge and insights.” 89 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Instilling a collective mind | Leadership attends to patterns of heedful interrelations whereby individuals recognize interconnectedness and cocreate group cohesion and shared purpose. | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Cultivating teamwork | Leadership cultivates the work environment to nurture team or group formation, development, membership, and effectiveness. | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Fostering emergent leaders | Leadership fosters dynamic interaction within the workforce such that leadership by members emerges at times for problem solving or to resolve tension or other moments requiring leadership action. | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 1 |

| Encouraging boundary spanning | Leadership attends to reaching across established borders in order to build relationships, gain information and resources, and form productive connections. This can be (1) vertical (across levels and hierarchy), (2) horizontal (across functions and expertise), (3) stakeholder (beyond the organization), (4) demographic (across diverse groups), or (5) geographic (across regions and locality). | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Anticipating the future | Leadership pays attention to the external environment and attempts to anticipate future possibilities, then works to continuously position themselves for future success. | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Developing formal processes | Leadership develops and assures implementation of officially recognized operational routines related to common, everyday processes and organizational functions in ways that align with vision and core values. | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

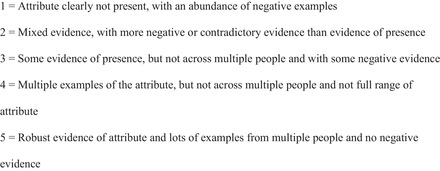

aSee Figure 2 for Practice Rating Scale.

Three of the authors (DC, JH, BFC) then read out loud all the text segments for each of the leadership codes, and after discussion and agreement, we created a brief descriptive summary for each leadership attribute in each practice and put these into a data matrix. We rated each attribute for each practice on a scale of 1 to 5 (Figure 2). As noted in Figure 2, we gave a rating of 5 only if there was robust evidence of the presence of the attribute with substantive examples and multiple people from different perspectives providing evidence without any contradicting examples. Conversely, we gave a rating of 1 only if there was no evidence of the presence of the attribute and there were abundant examples of an absence of the attribute.

Figure 2.

Practice Rating Scale Degree to Which Leadership Attributes Were Present

Results

Table 2 provides an overview of the nine practices included in this analysis. Five practices were system owned (Practices 1, 3, 4, 6, 8), with Practice 3 being part of a federally qualified health center (FQHC) system and Practice 8 being one of three small practices in a small rural system that functioned more like a physician‐owned practice than being part of a larger system. Two of the practice sites had five or fewer full‐time equivalent clinicians (Practices 1 and 8) and would be considered small practices. Four practices were located in urban areas with populations greater than 100,000 (Practices 2, 4, 5, 9) and three were located in communities with populations less than 20,000 (Practices 3, 7, 8). Two practices (Practices 1 and 6) were located in larger towns with populations between 20,000 and 35,000.

Table 2.

Descriptions of Nine LEAP Practices Selected

| Practice ID | Setting/Demographics | Leadership Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Practice 1 | Small clinic, part of large medical system 3 PCP FTE | The practice leader is the medical director who founded Practice 1. He is well respected and well read across sophisticated literature on QI, organizational change, and systems thinking. He has applied his long‐standing learning philosophy to practice, viewing change as constant and believing that systems need to be built to be nimble and constantly responding to change. Notably, he has made extraordinary efforts to level the hierarchy in the practice workforce through prioritizing numerous, regular office meetings that are facilitated to ensure that everybody can contribute. As a result, staff feel comfortable giving and receiving feedback, delegating and negotiating tasks, and dealing with interpersonal conflicts directly. Practice 1's leader has explicitly endeavored to develop a well‐defined culture that is solidified by written principles that are reviewed annually by all practice members. There is a strong sense of teamwork among clinicians and staff, aided by extensive and diverse forms of communication (eg, many formal meetings, one‐on‐one communication and mediation, and informal social conversation). The practice is constantly innovating and reflecting on lessons learned, and they have a history of breaking with convention to implement creative ideas. The leader reaches outside the discipline of medicine for ideas and pushes the boundaries of practice roles. |

| Practice 2 | Large, multispecialty practice 11.5 PCP FTE | Practice 2 is in a transitional phase. The former leader was a highly engaged, dynamic individual, and the practice continues to ride on her legacy. Since she left two years ago, a combination of people have stepped up to fill her shoes; however, they acknowledge that the former leader had many strengths they do not have. As a team, they tend to think a lot about strategies for future funding. The height of Practice 2's transformation efforts occurred approximately a decade ago when the leadership invested a lot into team building and practice redesign in response to financial challenges. Staff are given opportunities to develop and expand their roles and are encouraged to take classes to get more training. There is also evidence that staff feel encouraged to share their opinions and feel safe to do so. The leadership team has a vision for the practice that they try to spread, but there is a sense that it is not shared by the whole practice. This limits the extent to which clinicians and staff deliver care with a sense of teamwork. Although ideas for practice change tend to flow from the top, there are many forms of communication in place to ensure that information is passed to those who need to know, as well as opportunities for feedback to be given to those at the top. Formal processes are abundant, largely around processes for communication, as well as curriculum for trainings and health coaching. There is evidence of learning culture, at least among the leadership team, as leaders articulate with ease the lessons learned from their practice redesign efforts. |

| Practice 3 | Medium‐size FQHC, part of small health system 8 PCP FTE | The practice leadership team has a strong philosophical understanding of practice change and explicitly works to involve people in the process while building excitement about being an innovator in the field. In addition to being person‐centered, leadership is also financially savvy. They have created an extensive process whereby the entire practice is involved in the budget development annually, as well as a strategic planning process every few years. This reflects a general attitude of respect for all, regardless of position. Staff know they can question why things are done the way they are, and in general, people feel they can vent and be heard. Leadership has intentionally worked to instill a “culture of quality” mind‐set, and all staff are taught QI principles. There is evidence that “doing what's best for the patient” is a shared priority for everyone at Practice 3. There is a strong team mentality, facilitated by multiple opportunities for formal and informal communication (eg, monthly team meetings, biannual all‐staff meetings, and regular walks together for discussion and reflection). They seek practice transformation that touches all roles and recognize the value of learning from mistakes in their ongoing process. |

| Practice 4 | Medium‐size clinic within large health system 7‐8 PCP FTE | Practice 4 was founded by a physician who had a vision for a clinic with a social justice mission embedded into the local immigrant community. Along with two other physicians, she worked with the health system to establish this small clinic with staff hired from the community. Although there is constant effort from the lead physician to bring in new ideas and improve care, it is all with the aim of addressing social determinants of health, not anticipating future payment systems. This high‐energy, extroverted leader actively works to create an atmosphere of trust and camaraderie among all practice staff, and she has helped to cultivate a practice culture in which staff are acknowledged for their various skills and contributions. Their knowledge of the local community is especially valued, and they are respected members of the care team. The leader makes explicit efforts to give everyone a voice and to involve them in practice change efforts. There is a lot of evidence of staff coming up with change ideas that get implemented. They have several different types of staff and leadership meetings on a regular basis, as well as daily clinical huddles. They use abundant email to communicate between meetings, and clinicians and staff often have lunch together. Staff work outside their job descriptions, and all are cross‐trained to serve as either MA or receptionist. There is a strong sense of shared vision of community activism and social justice among the whole office, and the practice organizes services around the needs of the community. |

| Practice 5 | Medium‐size FQHC, part of large, national nonprofit health care organization 8 PCP FTE | Practice 5's leadership is a duo of a physician and a spiritually oriented clinical staff member with a mission to care for the underserved. There is strong evidence that this service mission is pervasive throughout the practice, and many report believing that patients can feel that. Leadership supports non‐clinicians to take on a great deal of responsibility and to fill leadership roles. Staff say they feel supported by staff‐level leaders who were promoted to lead daily operations. In addition, some MAs have different areas of expertise (eg, vaccines) that are recognized by the office. Staff and clinicians alike seem empowered to give input on change and to systematically try out new ideas. The model facilitates a workflow in which “everybody … come[s] together and work[s] through issues with the patient.” Practice 5 has various kinds of formal meetings, including monthly all‐staff meetings, meetings by group (eg, front office, back office, clinicians), and meetings of representatives from each role to work on QI. In addition to the many meetings, they have regular training sessions focused on using algorithms. Communication in the office is not just formal, however, as there is also evidence that people connect socially and form relationships with one another. |

| Practice 6 | Clinic within a large health system 6 PCP FTE | Innovation at Practice 6 is initiated at the system level, and individual clinics are selected to pilot specific QI projects, which are later spread to the rest of the system. Practice 6 demonstrates an innovative, forward‐looking orientation, as clinic leadership participates in systematic QI training and leadership development courses, which are supported by the system. This training, however, does not appear to be widely shared with front‐line staff. Nevertheless, there is evidence of clinic leadership's enthusiasm for innovative changes and for encouraging staff during times of change. Similarly, there are efforts to level the hierarchy of the practice workforce by allowing clinicians to be called by their first names, for example. While clinic leadership aims to create a safe environment, there is mixed evidence regarding the degree to which staff trust leadership enough to ask questions or express ideas. Although there is a shared vision at the level of system leadership, it has not translated to the clinic level. Despite the weak sense of shared vision, clinic physicians and staff do feel that they have learned to function as a clinical team. The commitment to the team is reflected, for example, in the lead MA's willingness to take on a great deal of responsibility, even serving as backup practice manager if all other leaders are unavailable. Practice 6 leadership is least active in promoting strong communication within the clinic. Meetings are infrequent and tend to be top‐down information‐dissemination events as opposed to forums for rich sharing of ideas. Communication within the system leadership is much stronger. Similarly, there are a plethora of formal processes higher up in the system, but very few trickle down to the clinic. Nevertheless, clinic leadership is invested in creating a learning organization and, consequently, make efforts to instill the message that it is “okay to fail” and to learn from failure. |

| Practice 7 | Medium‐size private practice, part of coalition of several practices 8 PCP FTE | Practice 7 is part of an IPA that formed to create a single organization. While they share a name, tax code, and some common objectives, each practice also has a lot of independence. Leadership exists at both the organizational level and the practice level, but the distinction is not always clear, since some individuals serve as leaders at both levels. One of the IPA founders, for example, regularly attends national conferences to bring ideas back to implement, particularly ideas that will help to position the practice for what they anticipate is coming down the pike in terms of reimbursement. Change at Practice 7 seems to be largely initiated at the central organization level, and leadership makes attempts to systematically spread it to each site. Change occurs through the implementation of new formal processes, not through leaders motivating and encouraging innovation and change. They have a formal QI process, in which staff are actively involved, with two to three “redesign teams” that meet monthly. The focus is on implementation rather than reflection and ongoing learning. The office is run in a traditional medical model, with staff functioning in conventional roles to support clinicians. There is some evidence that staff may not be comfortable giving honest feedback to their superiors. Although there is a fairly limited sense of the whole office sharing a collective vision, there is evidence that the clinical assistants do have a strong unity of purpose, and they go out of their way to help each other “keep patients flowing through the clinic smoothly.” |

| Practice 8 | Small clinic within a small clinic system 3 PCP FTE | The corporate office leadership of shareholders makes many decisions that are then enacted at the practice level. Practice‐level leadership is engaged and effectively motivates staff in QI and continual PDSA cycles. The lead physician brings tremendous passion and a bottom‐up philosophy about practice change. This translates into making efforts to have everybody involved in decision‐making and sending staff, not just the physicians, to corporate‐level meetings. Leadership has respect for office staff and feels it is important to give a consistent message in order to develop trust, as well as to reward staff for their work. They try to make staff feel safe to speak up, and they consider the big table in the lunch room to be an important tool toward this end, as it has become a place where staff and clinicians make it a point to share with one another. There are many different types of meetings that involve clinicians and staff, as well as social occasions for more informal sharing of ideas. The lead physician has had a large hand in helping to instill a shared value in investing in QI for the best patient care. Staff are empowered with standing orders and are able to step into each other's roles. This supports a strong team attitude that is driven by the sentiment that “every patient is everybody's patient.” |

| Practice 9 | Large, independent practice with 6 sites 6 PCP FTE | Practice 9 is widely recognized for practice innovations, especially in the use of technology. Practice changes are ongoing and tend to be implemented in a systematic way. One of the founding physicians at Practice 9 is the primary leader who leans toward a top‐down approach. Innovations generally originate with the leader, and other physicians and staff are engaged to implement them. There are strategies in place for clinicians to give input on change ideas; there is no evidence that other staff members have an opportunity to provide input. Practice staff are largely organized into traditional roles, and the leader regularly recognizes staff with monetary rewards for performance. There is a sense of warmth and friendship among staff, although there is little evidence of a strong sense of teamwork. Communication tends to be “lean,” such as electronic huddles. Practice 9 is not a “learning organization,” as it is not based on a mind‐set of learning through reflection, but the leader has successfully instilled a culture of continuous change. |

Abbreviations: FQHC, federally qualified health center; FTE, full‐time equivalent; IPA, independent practice association; MA, medical assistant; PCP, primary care physician; PDSA, Plan‐Do‐Study‐Act; QI, quality improvement.

In our analysis of leadership attributes, we found that all nine of the attributes identified from the literature, as well as the two additional attributes that emerged from our analysis, were evident and seemed important in most of the nine practices (see Table 1). With the exception of encouraging boundary spanning, which was less present than the others, each attribute had at least six practices with a rating of 4 or 5 for the attribute.

It is not surprising that a hallmark of innovators is anticipating the future; these practices think a lot about the future and how to position their organization to remain competitive. As the improvement specialist at Practice 1 noted, “I think part of our philosophy is that professionally if you want to stay competitive in this market that you always need to be looking at what's going to take you to the next level.” Sometimes practices considered strategies for future funding and were often early adopters of health information technology (HIT). These leaders were always looking for and implementing new ideas, including innovations with work roles and culture development. Ideas commonly came from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement or as a result of attending conferences. The lead physician at Practice 8 summed up this mentality, saying, “So I think it's always better to be at the head of the pack than the back,” as he anticipated payment changes and was also positioning the practice for the possibility of being acquired. Uniquely, one practice, Practice 4, was less focused on anticipating the future in terms of HIT or payment incentives, but rather invested tremendous energy into anticipating ways to accomplish their vision of addressing the social determinants of health (see Table 2). The medical director explained:

[P]romotion of health and the idea of health for us occurs by eradicating poverty…. So we have a thousand and one ways that we try and address poverty in our communities…. [I]f you want to talk about sort of the fundamental underpinning of everything we do, that's under everything.

Developing formal processes was also deemed important in all but one practice. In these practices, well‐articulated processes and protocols had been developed and implemented for numerous practice operations, communications, and improvement efforts. Although it was not explicitly stated by any of the leaders, the abundance of formal processes in these eight practices suggests that these leaders felt their visions could best be accomplished if important processes were formalized and not left up to chance. For example, at Practice 9 the medical director described their documentation processes and explained that these processes were established to achieve the practice's improvement goals. The field researcher's fieldnotes highlighted that at Practice 9, “It's not about documentation for compliance; it's about documenting so we can learn how we are doing, where we can improve, and how to improve.” They closed the office monthly for several hours to hold meetings, with different combinations of staff and clinicians, to review and discuss quality metrics and to conduct ongoing training for new processes and competencies.

Practice 1 had even more formal processes, including those for cultural development, hiring, cross‐training, leadership development, team‐based quality improvement (QI) and process improvement, communication, and collective decision‐making. Practice 4 had many similar formal processes. The medical director explained that the underlying rationale was to redesign work roles so that “everybody functions at the top of their license. That's a financial imperative for us.” She elaborated that they developed the details of their practice redesign by “serv[ing] as peer consultants to each other,” since they could not afford to hire outside consultants. “[O]ur strategy around engaging [the] workforce to come up with the solutions and then sharing that across [the workforce] has worked fairly well and has been much more engaging.”

Given the number of formal processes designed to maximize communication among the workforce, it follows that leaders in most of these practices paid attention to enhancing communication and information sharing. These practice leaders all created contexts to facilitate the sharing of information and forums for different kinds of formal and informal communication. For example, soon after Practice 2 began its first major transformation initiative, the practice leaders realized that abundant communication would be important for their success. The associate clinical officer described making a significant investment in formal meetings:

We did an enormous amount of team building. We sat around a table for two hours, once a week, with this team really sort of designing the whole, everything we wanted to do. Talking about it, role playing, doing all the education.

While the leaders at Practice 3 also recognized the value of creating forums for regular communication, they felt the informality of regular “walking meetings” provided an opportunity for both work‐related and social communication. Several practice members commented on the value of nurturing their relationships with one another through walking together. The office manager reiterated, “We go on our wellness walks…. We don't even need to talk about work, you know? You just go. But it's a good place to talk about work…. We almost walked to [the next town] one time by accident!” Leadership at Practice 8 also emphasized the importance of cultivating their relationships with one another, and the lead physician highlighted how incorporating personal, social communication into work meetings helped:

We have lunches together…. [W]e chat around this table. I still think of those tables as our secret weapon. The fact that you can get most everybody around one table and you can actually have a real dialogue, a real conversation with people. It doesn't have to necessarily be about work. It can be about family, your new baby, whatever. I think that's extremely helpful.

Prioritizing strong communication and relationships among the practice workforce was an important way that practice leaders worked on managing abuse of power and social influence. This was often demonstrated in leaders’ efforts to flatten the organizational hierarchy. Sometimes leaders expressed these efforts through verbal attempts to change attitudes relating to traditional practice roles. For example, the Practice 3 fieldnotes characterize the practice leadership with an example of one of the leaders regularly reminding staff, “Don't say ‘I'm just a nurse’ [or] ‘I'm just a MA [medical assistant].’ You are a nurse or MA, and that means you are helping your patients be healthier.” Similarly, the office manager in Practice 1 talked about the importance of emphasizing the similarities between them, regardless of their different roles:

There are people who are “Oh, the manager.” … I have to work really hard to bring that down a little bit to say we're not that different. Yes, my responsibilities are different, but I have feelings, I get annoyed, I have my good days, bad days.

The field researcher's fieldnotes from Practice 1 summed up this pervasive attitude: “When asked about the chief innovation in the clinic, many of the staff … see leveling the hierarchy as the core innovation. They view this as the chassis on which all else is built for QI and staffing improvement.”

Another way some leaders described working to flatten the hierarchy involved formally including staff in decision‐making. At Practice 3, the entire workforce was invited to participate in the annual budget and strategic planning meeting.

We start in around August, asking [department directors] what kinds of things they would like to change for the coming year. Ask them to collect input from their staff and their teams. And it's a very iterative process we have. So this year we had 27 [staff] … participating in our budget process.

—Executive Director

Making efforts to level the hierarchy does not mean that all practice decisions are subject to a collective process. Some leaders spoke explicitly about considering which kinds of decisions should involve whom. For example, during an interview with the Practice 7 leadership team, they explained that the practice involves different decision‐making bodies differently, “depend[ing] on the enormity of [the decision] and who all is going to have to be invested in it in order to make it work.”

The three of us [leaders] will sometimes noodle things before we even decide should it even go to core. We're sort of a filter and we'll informally have sort of doctor talk about stuff before it gets out there, and I think that saves a lot of stuff coming to the core team that would take up a lot of time.

—Medical Director

Related to issues of managing power and social influence, most practices also had robust processes in place for “fostering emergent leaders.” The medical director at Practice 2, for example, described in a group leadership interview that he intentionally stepped back from being the QI team leader to give others an opportunity to develop as leaders: “[W]e started to say we needed to find a way to train new leaders and to get other people up to snuff.” The chief clinical officer added, however, that not everyone has the inclination to become a leader and that “some people feel like they're overloaded, so to take on to become a team leader is just another part of a job they don't really want to volunteer for or step up for.” For those with the desire, though, he felt it was important to provide the opportunity, and he recalled how the former medical director had done this for him.

Leadership at Practice 1 shared a similar attitude toward nurturing individuals’ development as leaders, and they formalized it into an emerging leaders program. The practice administrator described how the current leadership completes an annual leadership assessment in which they reflect on the leadership potential of everyone in the office. Based on this assessment, they invite specific individuals to participate in the program; others who expressed interest were also welcomed. In addition to helping staff grow professionally and personally, this emergent leader program was also part of succession planning, thinking ahead to when Practice 1's well‐loved founder retires. The behavioral health counselor explained that the program was designed around the assumption that it is not essential for the future leaders to have a position of authority to be effective, “but somebody has to have the knowledge, the understanding about [the practice philosophy], and care enough to maintain the principles.”

Generating a learning organization was also important to these practices. There was evidence that these practices valued ongoing learning, and they formalized a way to prioritize it by creating forums for regular reflection on experiences as well as ongoing innovation and improvement efforts. For instance, Practice 5 had multiple QI teams working simultaneously on different change initiatives, as well as monthly meetings for each role and an office‐wide meeting. Cycles of action and reflection occurred in all meetings, but the spirit of ongoing learning was especially highlighted in the office‐wide meetings, as described by the behavioral health manager: “[W]e really come together and say what is this? Why are these numbers not going up? Why are these numbers coming up? What are we doing well? What are we not doing well? And it's not a judgment thing; it's just a, ‘Okay, let's try this.’”

At the time of data collection, Practice 3 was actively reflecting on its change strategy. The practice had been in a lengthy process of “major transformation in every role,” and staff and clinicians had been showing signs of change fatigue. The medical director talked about how practice leadership was gaining insight into how “disruptive” all these changes had been and realizing that there was no end in sight. “I think we're going to be in change for a long time.” He explained that the QI team was currently in a process of evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of how they had been implementing new workflows. Their reflections led to considering a new approach: “We may need to have a smaller group do the really disruptive stuff and then roll out to a bigger group, so not everybody's going through that change all at the same time.”

In Practice 6, change initiatives originated with the leadership in the larger health system of which the clinic is a part. The system offered a leadership program for practice site leaders. The clinic administrator at Practice 6 had been a participant and described some messages from this program that highlight principles of a learning organization, which she was working to implement:

[Y]ou have to tell people you will fail and it's okay…. [I]t can be very discouraging to put a lot of work into something and then not have it work. And you have to celebrate that, and communicate more than you ever thought you had to, and take the time to talk to people and get their feedback and let them have the ideas.

Instilling a collective mind was highly apparent in two‐thirds of the practices. One way leaders worked to accomplish this was simply to reiterate the practice mission often, so that it became an integral part of office culture. For example, when the customer service director at Practice 3 was asked about the secret behind their practice culture, she answered, “[I]t's mission‐driven, and we keep bringing it back to that…. Every time we start something we talk about the mission around it and I think that [is] super empowering.” Another strategy to instill a collective mind was to hire for “interest in the mission,” as described by 2 of the leaders in Practice 5. The executive director explained that he was aware that clinicians could earn more at another practice; nevertheless, some candidates for clinical positions were clearly attracted to Practice 5's strong sense of mission “to serve the underserved … regardless of ability to pay.”

The practice administrator at Practice 1 gave insight into the development of their strong sense of collective mind by describing a period when the practice was going through an extensive redesign process:

It was the cultural changes that were difficult for people. It was very difficult and we really wanted to give people time to make the changes; we didn't want to come in and say, “Well, this is what we're doing; you take it or you hit the road.” So it meant that we introduced the concept and then we try to implement and then we get pushback…. There were people who just said, “I'm not interested in this,” and we were saying …, “We're willing to be patient but you must come along.”

There was one staff member who “refused” to go along and was consequently let go. Everyone who remained developed a strong sense of collective mind through the process.

Given the focus of the PCT‐LEAP project, it is unsurprising that many of the leaders put a great deal of emphasis on cultivating teamwork among their workforce. Practice 5, for instance, was described as having “one of the most solid implementations of team‐base care” the field researcher had ever seen. One of the cofounders put this into context by explaining that the practice started very small, and so “by necessity” everyone was cross‐trained:

If you start out with 4 or 5 people working together, then you sort of need to have the attitude of, if the phone rings and everyone else is busy, you're going to answer it; doesn't matter if you're the doctor or the medical assistant or what.

The culture that consequently developed was inherently team‐based, and the leaders cultivated it over time. An MA echoed this characterization of the practice culture: “[W]e work very well as a team. We help each other. If one person is behind or they need help … we just step right in.” When asked how she thought that culture of being helpful to one another came about, she explained, “When we have our staff meetings, [practice leaders] always talk about …, ‘You have to think of it as how would you like your mom to be treated at a clinic?’” She believes that is key to their exemplary team‐based care.

Similarly, an MA at Practice 8 attributed the high level of teamwork to two factors: clear expectations from leaders and widespread buy‐in from staff. “We know what their expectations of the clinical staff [are] … everybody has the same expectations…. [A]ll of us kind of stand behind those expectations. We demand team players.” She summarized the predominant attitude: “That's what it is, everybody being on the same team; no one ever saying, ‘That's not my doctor; I don't have to do it.’”

Assuring psychological safety among the practice workforce was also a high priority for many of these practice leaders. When Practice 2 was in the process of transforming the MA role to include health coaching, the leadership team was sensitive to the MAs’ feelings during this time of transition. For example, they started with only the MAs who had expressed interest in expanding their role and did not make it a requirement for everyone. The chief clinical officer further explained:

Even though a lot of them knew they could do it and they wanted to do it, it was very frightening for them, so we actually had a person [psychologist] who came in and spent time with them … [b]ecause they felt this was not what they went to school and learned…. But telling that to somebody, how do you do that?

Leadership helped MAs to feel safe expressing their feelings by showing respect for their fears and factoring in time for extensive training, debriefing, and “a lot of hand holding,” as described by the medical director, until MAs felt confident in their new roles.

While the medical director at Practice 2 made it clear that he prioritized having a practice where staff at all levels felt comfortable sharing their opinions, he also noted that it is a skill not all leaders have. He felt a mistake that physician leaders commonly make is to believe that “being the team leader is leading … [;] you tell everybody what to do.” He added that, ideally, leaders “really work at drawing out other people, getting them to participate.” The customer service director at Practice 3 offered an insight about drawing people out. She had noticed that psychological safety was facilitated when the practice leaders were also willing be honest and vulnerable with the staff:

I think leadership in the past has been afraid sometimes of sharing all the information, which then we get complaints about. “Well, you're not being very transparent,” or “It goes there and it never comes back.” And it's not that it didn't go there, and that it's not being thought about, it was that no one was saying …, “I don't have the answer yet but it's on my plate.” … [T]hat's something we've been working on … [T]hat makes people feel listened to and valued.

The medical director at Practice 8 also valued having a psychologically safe work environment, but he emphasized that clear expectations and accountability helped facilitate it. Each team was “held accountable” if the expectations were not met. This helped to eliminate blame of individuals and left the team to “figure it out” together to identify where there was a “disconnect” within the team. The medical director felt this approach encouraged physicians to problem‐solve with their teams. To illustrate, he described a mistake he has seen new doctors sometimes make: “It's not that they're bossy and it's not that they're awful; it's the opposite—exceedingly nice. But they don't know how to have an expectation of someone they work with.” The art of “really work[ing] well with a team,” this medical director cautioned, is not just a matter of being “nice.”

With the exception of one practice, there was a clearly identifiable, engaged, individual leader who was a driving force for setting the practice's vision and motivating change. This could be fleeting, however, such as in Practice 7, where the leader became engaged at the system level and subsequently had minimal direct impact at the practice level; or in Practice 2, where the leader had left and nobody had stepped up to fill this role. Nevertheless, many of the practices paid attention to motivating others to engage in change. An engaged leader was typified by the founding medical director at Practice 1, who was deeply committed to practicing the principles of “servant leadership.” As he described it, “You earn your authority, and then you sort of turn the organizational pyramid upside down. So you put the bottom on the top, the base on the top, and the head of the organization is at the bottom.” Although he had a reputation for being well read across sophisticated literatures on quality improvement, organizational change, and systems thinking, there was evidence in the data that this was more than an intellectual interest:

I thought it was the right thing to do. I'd read some about quality management and read some articles about Deming's, and it just again— It connected with me at a level I thought, wow, this makes sense to me…. [T]he whole idea of people [who are] doing the work making decisions about the work, just felt very natural to me.

By comparison, the lead physician at Practice 8 brought passion with a bottom‐up philosophy of engaging staff but did not take an academic approach to QI nor use a particular QI model. He described himself as someone who “like[s] the trenches,” with an implied contrast to an academic interest. Staff described how he motivated through pure enthusiasm. The clinical supervisor, for instance, recalled how he would sometimes walk through the hallways talking about how wonderful everything was at Practice 8.

[H]e was so proud of this clinic and thinking this was the best place in the world, and believed in it and was so loyal to it…. I think when he took that pride and that stuff, it makes the people that work here kind of hop onboard with that too.

The leadership attribute found least often in these practices was encouraging boundary spanning. The types of boundary spanning most clearly demonstrated were “vertical” and “horizontal” (ie, across levels/hierarchy and across functions/expertise, respectively). In terms of vertical boundary spanning, the lead physician at Practice 1 demonstrated it most overtly with his aim to invert the organizational hierarchy. A concrete way he attempted to do this was to teach communication skills in office‐wide workshops to empower everyone to give constructive feedback, regardless of their roles. Practice members shared several anecdotes illustrating crossing hierarchical boundaries in communicating feedback. A patient service representative described the first time she initiated a conversation with the lead physician to give him feedback about his habit of calling patients to come pick up prescriptions before the prescriptions had arrived in the office:

[O]ne day I said, “I need to talk to with you.” … “When you call a patient to tell them their prescription's ready and they come in to pick it up and you're not here, the prescription's not there, and I can't help them, it makes me feel foolish and then the patient has to come back.” And he looked at me and kind of smiled and he said, “I'll do better next time.”

She added that he did.

The most common examples of horizontal boundary spanning, where the boundary between functions and expertise is crossed, involved practices where the leadership decided to cross‐train staff to share responsibilities. Practice 4 provided a clear illustration because it developed its practice culture from the beginning with the assumption that everyone would be responsible for all office and patient needs, within their licensure. The lead physician described that it had been an interest of hers to develop a workforce that functioned collaboratively across role boundaries, and she “look[ed] for that attitude” in hiring staff. Consequently, the refrain she had commonly heard at other practices—“No, that's not my job; someone else should do that”—was absent at Practice 4.

In addition to vertical and horizontal boundary spanning, there were a few instances of “stakeholder” boundary spanning in these practices. For example, the lead physician at Practice 9 went outside the discipline of family medicine to get input on his innovative approach to diabetes care and, as he explained, developed a fruitful collaboration with a prominent university diabetes center. He candidly described the risk‐taking involved in crossing this disciplinary boundary:

People said, “Have you lost your mind? You want to go to [a prestigious university] and tell them how you are treating diabetes?” I said, “Yeah, I wonder if we are doing a good job.” I was willing to be a fool. And lo and behold, we're doing something [that they got] excited about … and that has developed into an 8‐year relationship that resulted in our joint diabetes center.

Discussion

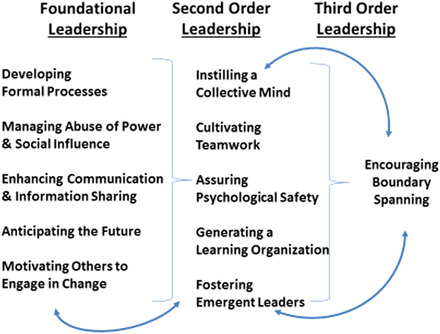

We uncovered and described 11 leadership attributes that appear to be important for primary care practices during times of change and innovation. These attributes help to unpack the critical building block of engaged primary care practice leadership in the Bodenheimer model, 24 and to identify actions that have been taken by practice leaders in high‐functioning practices. Although we found that all 11 attributes are important, we also noticed that the frequency of high ratings for these attributes varied across the nine practices (Table 1). Complexity science theory and management literature supports the idea of a developmental model for focusing leadership attributes and behavior. 43 , 44 , 46 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 In its simplest form, a complex adaptive system is a dynamic network of nonlinear interacting agents with the key features of self‐organization, connectivity, coevolution, and emergence. 113 When leading a practice through the lens of complexity, one focuses less on prediction and control and more on fostering relationships and creating the conditions for successful adaptation and emergence. From this perspective, complexity science management theory suggests that generating motivation, building self‐organizing capacity in the form of internal models and attractors, and enhancing awareness of the environment with which you are coevolving must occur first. This is followed by developing the skills and conditions for learning well together and generating emergence and innovation. 40 , 110 , 111 , 112 Based on these features and principles, as well as our analyses, we hypothesize and propose a developmental model in which some leadership attributes are foundational and necessary before addressing the others (Figure 3).

igure 3.

FA Developmental Model of Primary Care Practice Leadership [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com] [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In this model, we propose that the development of these 11 attributes occur in three levels or stages. First, there is a foundational level that includes the five attributes directly related to building self‐organizing capacity, motivation, and landscape awareness: developing formal processes; enhancing communication and information sharing; managing abuse of power and social influence; motivating others to engage in change; and anticipating the future. Specifically, in all the practices we studied it was apparent that an important early task for leadership is to develop and implement officially recognized operational routines related to common processes and organizational functions in ways that align with the practice vision. These might include clearly defined and flexible roles, clear lines of accountability, personnel policies, training and development, workflows, and succession planning. Outlining these types of formal processes can also help leadership manage issues created by power inequity and differential social influence within the workforce, including managing abuse of power through mitigating bullying, freeloading, and cheating. Equally as fundamental is setting up effective communication and information sharing so that policies and expectations are clearly understood and there are venues for discussion and feedback. Additionally, in this foundational stage, leaders need to invest in motivating others to engage in change, as well as plan for the future by anticipating change. It is thus at this stage that leaders focus on developing a mind‐set for change and trust within the office, as well as creating some basic operational infrastructure to support these efforts.

Identifying these five attributes as foundational does not mean they are inherently more important than others. Complexity science posits that there is a great deal of interdependence among the characteristics of a system and that they are emergent over time. We placed the five foundational leadership attributes first in the model because they establish the conditions that better enable the enactment of the others. That is, once the foundational strategies are underway, efforts can begin toward instilling a collective mind, cultivating teamwork, assuring psychological safety, fostering emergent leaders, and generating a learning organization, the prerequisites for effective innovation and adaptive emergence. For example, to achieve psychological safety it is necessary to first manage abuse of power, establish clear channels for communication and information sharing, and implement formal processes to minimize chaotic operations and help the practice workforce feel confident in executing their interdependent roles. Thus, even though ensuring psychological safety is crucial during times of change and innovation, it is a second‐order attribute and not foundational because necessary conditions must be established from which it can emerge and be maintained.

The skills and strategies associated with these ten attributes should be in place before working on the third‐order attribute: boundary spanning. This attribute is multidimensional and benefits from the synergy of a number of foundational and second‐order attributes. As one example, anticipating the future can powerfully inform the ongoing visioning and missioning of the practice. When the vision matches the emerging future, it is much easier to motivate others to engage in practice change. Having buy‐in and engagement in change across the workforce can thus make vertical and horizontal boundary spanning easier and more effective. Similarly, such boundary spanning can enhance other attributes such as communication and information sharing, managing abuse of power and social influence, and teamwork. Additionally, anticipating the future can inform budgeting and programming decisions, which often require stakeholder boundary crossing through connecting with external resources, scanning literature, discovering emerging trends, and translating that information into vision, budget, and practice activities. Although this model places leadership attributes in a developmental order, they are interdependent and their emergence can be cyclical and mutually reinforcing.

This study and our proposed model are not without limitation. For example, we examined only practices that were selected as innovators, so we are not able to determine if these attributes are present or lacking in practices that are more typical. However, as noted elsewhere in this manuscript, results on primary care interventions in the published literature often cite leadership deficits as a major contributor to failure of interventions. 21 , 29 , 36 , 51 , 52 , 114 , 115 This literature essentially serves as a comparator group for the LEAP practices we studied. Thus, we think the findings in these “high‐performing practices” give credence to how the leadership attributes should show up elsewhere, but further research is required to support the model.

As we look to the future of our rapidly changing health care environment, we would do well to answer the question of how we will train the next generation of leaders in primary care. 104 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 Leadership matters and investments should be made to ensure the country transitions to new models of care. In the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation primary care demonstration projects and the implementation of primary care extension, there is almost nothing built in about leadership development at the practice or system level. There currently exists a number of leadership learning opportunities, including one that emerged directly from the LEAP program. 119 For example, executive leadership training is available at the Kansas University Medical Center program for individuals interested in leading community health centers (http://www.chcexecfellow.com/about-the-fellowship.html), while Primary Care Progress offers specific leadership training opportunities to primary care clinicians (http://www.primarycareprogress.org/leadership). State professional societies and chapters can also provide leadership training. Nevertheless, our analysis suggests that to be comprehensive, programs like these should assure they are addressing the full range of leadership attributes.

Support/Funding

This work was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, providing funding for the PCT‐LEAP project (grants #69788 and # 71986).

Acknowledgments: Late Rueben R. McDaniel, Jr. was very instrumental to the conception of this work and the early thinking that lead to the current manuscript.

References

- 1. Blumenthal D, Epstein AM. Quality of health care. Part 6: the role of physicians in the future of quality management. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(17):1328‐1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]