This observational study assesses the percentage of clinical trials with limitations in 4 domains that led to US Food and Drug Administration approvals from June 30, 2014, to July 31, 2019.

Key Points

Question

How often are anticancer drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) based on clinical trials with the following limitations: nonrandomized design, lack of demonstrated survival advantage, inappropriate use of crossover, or the use of suboptimal control arms?

Findings

In this observational study, 187 trials leading to anticancer drug approvals between June 30, 2014, and July 31, 2019, were reviewed. A total of 125 (67%) trials leading to anticancer drug indications had limitations in at least 1 of the 4 domains of interest.

Meaning

Despite the increase in the number of drug approvals by the FDA, a substantial number of drugs are authorized based on data that do not demonstrate efficacy over established standards of care.

Abstract

Importance

While there have been multiple assessments of clinical trials leading to anticancer drug approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the cumulative percentage of approvals based on trials with a limitation remains uncertain.

Objective

To assess the percentage of clinical trials with limitations in 4 domains—lack of randomization, lack of significant overall survival advantage, inappropriate use of crossover, and use of suboptimal control arms—that led to FDA approvals from June 30, 2014, to July 31, 2019.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This observational analysis included all anticancer drug indications approved by the FDA from June 30, 2014, through July 31, 2019. All indications were investigated, and each clinical trial was evaluated for design, enrollment period, primary end points, and presence of a limitation in the domains of interest. The standard-of-care therapy was determined by evaluating the literature and published guidelines 1 year prior to the start of clinical trial enrollment. Crossover was examined and evaluated for optimal use. The percentage of approvals based on clinical trials with any or all limitations of interest was then calculated.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Estimated percentage of clinical trials with limitations of interest that led to an anticancer drug marketing authorization by the FDA.

Results

A total of 187 trials leading to 176 approvals for 75 distinct novel anticancer drugs by the FDA were evaluated. Sixty-four (34%) were single-arm clinical trials, and 123 (63%) were randomized clinical trials. A total of 125 (67%) had at least 1 limitation in the domains of interest; 60 of the 125 trials (48%) were randomized clinical trials. Of all 123 randomized clinical trials, 37 (30%) lacked overall survival benefit, 31 (25%) had a suboptimal control, and 17 (14%) used crossover inappropriately.

Conclusions and Relevance

Two-thirds of cancer drugs are approved based on clinical trials with limitations in at least 1 of 4 essential domains. Efforts to minimize these limitations at the time of clinical trial design are essential to ensure that new anticancer drugs truly improve patient outcomes over current standards.

Introduction

Clinical trials leading to marketing authorization of anticancer drugs by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are heterogeneous, with varying strengths and weaknesses. Nonrandomized clinical trials that show tumor shrinkage in response to a novel therapy are limited by uncertainty as to whether these agents are superior to the prevailing standard of care or if they improve survival or quality of life. When randomized clinical trials (RCTs) are conducted, limitations of interest may be related to trial design, for example, using a control arm that is considered suboptimal or inappropriate use of crossover, or in outcome, such as failing to demonstrate an overall survival (OS) benefit when an improvement in a surrogate end point is met.

Prior studies have characterized the frequency of single-arm studies leading to drug approval1 and the use of surrogate end points.2 We previously assessed the frequency of substandard control arms.3 However, these studies did not assess errors of crossover and the cumulative percentage of these limitations coexisting in the same trial. For example, what percentage of FDA approvals are made on the basis of improved survival in a trial without limitations?

Crossover in cancer RCTs occurs when a patient randomized to the control arm is given the investigational therapy after disease progression or toxic effects (unidirectional crossover). There are 2 errors of crossover in trials. The first occurs when crossover from the control arm to the investigational agent is allowed without established efficacy of the investigational agent. In these cases, crossover from control arm to the investigational agent can confound interpretations of end points, such as OS, and may even lead to spurious survival benefits.4,5 For instance, in a study of a novel, unproven cancer therapeutic vaccine in prostate cancer, crossover resulted in fewer patients receiving docetaxel and only at a delayed time point, which may have harmed the control arm.6 Survival differences in this setting could be due to either a successful therapy or harm to the control arm.

The second error is to omit crossover when a drug has proven benefit in a subsequent line of therapy, when a trial seeks to advance the agent to the frontline setting. For instance, in a study evaluating pembrolizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor, for previously untreated programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1)–expressing metastatic non–small cell lung cancer, omission of crossover resulted in fewer patients being offered pembrolizumab—an agent that had been approved in the second-line setting—after progression on the control arm.7 Here, crossover is mandatory, and its absence may lead to the false inference that early administration is superior to the current standard of care (ie, sequential treatment). We sought to perform a single analysis that examined all 4 of the aforementioned limitations in a modern cohort of cancer drug approvals using a comprehensive resource and estimate the frequency of these limitations coexisting in the same trials.

Methods

We sought to assess what percentage of clinical trials leading to new or supplemental marketing approvals of anticancer drugs by the FDA had any of the following limitations: (1) nonrandomized clinical trial design, (2) RCTs that failed to show an OS advantage, (3) RCTs that used a suboptimal control, and (4) RCTs that inappropriately used crossover. This study of published reports did not involve patient-identifying data and was not submitted for institutional review board approval.

Data Set

We examined all approvals by the FDA from June 30, 2014, through July 31, 2019. Inclusion criteria were all indications for every single novel anticancer drug approval in adults (≥18 years). Novel anticancer drugs were identified using the FDA hematology/oncology approvals and safety notifications web page8 and tabulated. Then, the name of each novel anticancer drug was entered into the FDA approved drug products search engine.9 Approval date(s), history, and labels (including new indications) were extracted. Notably, our prior study of control arms relied exclusively on the FDA hematology/oncology approvals and safety notifications web page,8 which does not report on new or expanded marketing approvals for an already approved investigational agent (eg, ibrutinib vs ofatumomab in previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia).

Every clinical trial cited on the drug label at the time of marketing authorization as the basis for an FDA approval was identified using the National Clinical Trial identifier on the label and confirmed by reviewing the FDA approvals and safety notifications web page when listed. The trial article was identified using PubMed, and the protocols were reviewed if available with the published article in the supplement. The FDA statistical review reports were not used because many were not accessible and/or not available for supplementary indication approvals. From the article of each trial, we identified the accrual period, setting of the clinical trial (national vs international), indication, control arm, primary end point, OS end point, and the presence or absence of crossover in RCTs.

Assessing the Control Arm

For each RCT, we assessed the quality of the control arm as suboptimal if (a) restrictions were placed on the choice of control that excluded another potentially equivalent agent, or (b) the control arm was specified but not the recommended agent and potentially inferior (eg, the control arm was a single agent when doublet therapy is recommended). We then evaluated whether a suboptimal control arm was chosen because of the international scope of the trial and would not have been considered a US standard-of-care option.

We assessed control arms using 2 methods independently. First, the first and second authors (T.H. and M.G.-V.) performed a search of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines through the Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (JNCCN) dated at least 1 year prior to the start of accrual of an RCT of interest that led to an FDA marketing authorization to determine the standard-of-care therapy for each specific cancer. When guidelines were not available for the year of interest in JNCCN, we used the Wayback Machine, a digital archive that stored previous versions of NCCN guidelines. Second, the first and second authors separately and independently read the published clinical trial data presented in articles as well as the appendices and supplements, when relevant, and determined the adequacy of the control arm compared with what would be considered the standard of care 1 year prior to the start of trial accrual. Conflicts were resolved by the third author (V.P.).

Assessing Crossover

We assessed for the presence or absence of protocol-specified unidirectional crossover from published articles and by searching protocols available with the articles. Two authors (T.H. and M.G.-V.) determined separately and independently whether the presence or absence of crossover was desirable based on established definitions.5

Appropriate crossover was defined as allowing crossover in situations where the efficacy of the investigational agent had already been established from a previous RCT in a latter line of therapy (eg, second line or beyond), had an FDA approval in a latter line of therapy, or was considered the standard of care in a subsequent line at the time of or within 1 year of enrollment of participants. In these situations, the absence of crossover in the protocol or the absence of a protocol amendment was deemed inappropriate.

Inappropriate crossover was defined as use of crossover in situations where the fundamental efficacy of an experimental agent had not been established in a prior RCT, and/or an FDA approval was not available at the time of or within 1 year of enrollment of participants. In these situations, the presence of crossover was considered inappropriate, as it has potential to obscure signals of true benefit (eg, OS advantage) or harm from the investigational agent (both arms of the trial will receive it). A protocol amendment made during study periods to allow crossover when a drug was approved by the FDA or an RCT confirmed its efficacy in a latter line setting was considered appropriate.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported throughout. We analyzed the study data from November 1 to November 20, 2019.

Results

Between June 30, 2014, and July 31, 2019, the FDA granted 176 approvals for 75 distinct novel anticancer drugs based on 187 trials. The number of anticancer trials leading to FDA approval doubled over time with 68 in the first half of the study period (June 2014 to December 2016) to 119 in the second half of the study period (January 2017 to July 2019). Of the 187 trials, 123 (66%) were RCTs, and 64 (34%) were nonrandomized clinical trials. Of the 187 trials, 38 (20%) were for lymphoid malignant neoplasms, 37 (20%) for lung and head and neck malignant neoplasms, and 19 (10%) were for genitourinary malignant neoplasms. To better characterize these limitations, we separated them into limitations in design (uncontrolled study, suboptimal control, inappropriate use of crossover) and limitation in outcome (lack of OS benefit).

Limitations in Design

Nonrandomized Trials/No Control Arm

We found that 64 of 187 (34%) pivotal trials lacked a control arm. Two drug indications were based on data from a subset of patients in an open-label phase 1b trial (eg, KEYNOTE-013, pembrolizumab in refractory primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, after 2 or more lines of therapy10) and a post hoc analysis of a subset of patients from multiple trials (eg, LUX-Lung, afatinib in first-line metastatic non–small cell lung cancer without resistant EGFR mutations11). The remainder were largely single trials or pooled analyses of 2 single-arm trials. The primary end point was overall response rate in 53 trials (83%) and complete remission in 5 trials (8%). The majority of marketing approvals based on nonrandomized clinical trials (43 trials [67%]) were granted under the accelerated approval program.

Suboptimal Control Arms

There were 123 RCTs leading to 120 approvals. The majority of drug indication approvals (117 [97%]) were based on data from a single RCT, while the remainder (3 [3%]) were based on data from 2 RCTs. The majority of approvals based on RCTs (110 [92%)] were regular approvals. Of the 123 RCTs, 1 was a noninferiority trial and 122 were superiority trials.

Of the 122 RCTs powered for superiority, 31 (25%) had a suboptimal control arm. A list of all RCTs with a suboptimal control arm and the reasons they were deemed suboptimal is provided in eTable 1 in the Supplement. When categorized by type of suboptimal control, 22 (71%) clinical trials omitted active treatment in the control arm by using a control known or likely to be inferior to other available agents or not allowing combinations, and 9 (29%) limited the investigator’s choice in selecting an active treatment. When assessed by whether the international scope of the trial led to a suboptimal choice of the control arm in the US, 3 (10%) trials chose a control arm that was deemed more accessible outside the US but that may not have been the treatment of choice in the US. Of the 31 RCTs with a suboptimal control arm leading to FDA approval, 1 was reversed due to a subsequent phase 3 trial showing a lack of superiority over the control.12

Inappropriate Inclusion or Omission of Crossover

Of the 122 clinical trials powered for superiority, 17 (14%) had errors in crossover (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Of those, 8 (47%) prespecified crossover in the protocol when crossover was not desirable (ie, crossover to the investigational agent was allowed on disease progression in the control without previous studies or FDA approvals establishing efficacy of the investigational treatment in a latter line of therapy), and 9 (53%) did not prespecify crossover in the protocol when crossover was desirable (ie, crossover to the investigational agent was not allowed despite the established efficacy and/or FDA approval of the investigational agent in a latter line of therapy).

Limitations in Outcome: Resulting OS

The primary end point was progression-free survival in 63 of 122 clinical trials (51%), OS (primary or coprimary) in 38 (30%), and an alternative surrogate end point in 23 (19%). Overall survival was either a primary or a secondary end point in 121 RCTs (98%). One was a noninferiority trial with OS as a primary end point.

Of the 122 RCTs powered for superiority, OS was superior in the investigational arm in 65 trials (52%), failed to show advantage in the investigational arm in 36 trials (30%), was not reported at the time of analysis in 19 trials (16%), and was not a prespecified end point in 2 trials (2%), one of which would have been desirable.

Cumulative Limitations

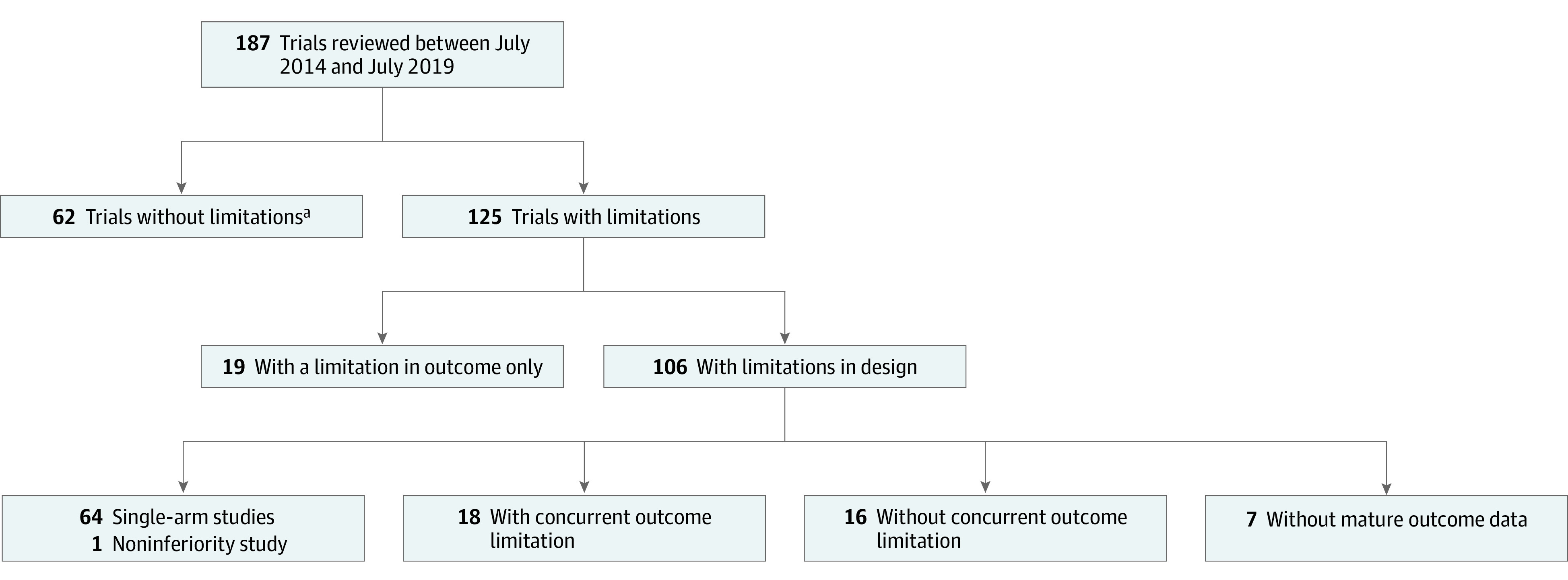

Among 187 trials, we found that 125 (67%) were trials with limitations in design and outcome. Specifically, 106 (57%) had limitations in design, 37 (20%) had limitations in outcome, and 18 (10%) had concurrent design and outcome limitations (Figure). The Table summarizes the limitations among RCTs and those without mature OS data as of November 2019.

Figure. Flowchart of All Cancer Drug Trials From July 2014 Through July 2019.

aIncludes 12 trials without design limitations but with immature outcome data.

Table. Patterns of Limitations in Randomized Clinical Trials.

| Trial | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier | Drug, indication | Category of limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| AETHERA | NCT01100502 | Brentuximab vedotin, classical HL after ASCT consolidation | OS advantage not proven Crossover error |

| ALCANZA | NCT01578499 | Brentuximab vedotin, pcALCL, or CD30-expressing mycosis fungoides in patients who received prior therapy | OS advantage not proven Suboptimal control arm |

| ALCYONE | NCT02195479 | Daratumumab, newly diagnosed multiple myeloma in patients who are transplant ineligible | Suboptimal control arm |

| ALEX | NCT02075840 | Alectinib, ALK-positive metastatic NSCLC, first line | OS advantage not proven Crossover error |

| ALFA-0701 | NCT00927498 | Gemtuzumab ozogamicin, previously untreated AML | OS advantage not proven |

| APHINITY | NCT01358877 | Pertuzumab, adjuvant treatment of ERBB2-positive early breast cancer with chemotherapy and trastuzumab | OS advantage not proven |

| ARAMIS | NCT02200614 | Darolutamide, nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | Suboptimal control arm |

| ARCHER1050 | NCT01774721 | Dacomitinib, first-line metastatic NSCLC with EGFR exon 19 deletions or exon 21 L858R mutations | OS data not mature |

| ARIEL3 | NCT01968213 | Rucaparib, maintenance for recurrent ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer, at least 2 prior lines of therapy | OS advantage not proven—planned interim analysisa |

| ASCEND-4 | NCT01828099 | Ceritinib, metastatic ALK-positive NSCLC | OS advantage not proven Suboptimal control arm |

| AUGMENT | NCT01938001 | Lenalidomide, follicular lymphoma and marginal zone, previously treated (with rituximab) | Suboptimal control arm Crossover error |

| AURA3 | NCT02151981 | Osimertinib, metastatic EGFR T790M-mutated NSCLC after progression | OS data not mature |

| AURELIA | NCT00976911 | Bevacizumab, platinum-resistant, recurrent ovarian cancer with paclitaxel and liposomal doxorubicin | OS advantage not proven Crossover error |

| BFORE | NCT02130557 | Bosutinib, first-line chronic-phase CML | OS advantage not proven Suboptimal control arm Crossover error |

| BRIGHT AML 1003 | NCT01546038 | Glasdegib, newly diagnosed AML in 75 or older or who have comorbidities | Suboptimal control arm |

| CABOSUN | NCT01835158 | Cabozantinib, first-line RCC, intermediate and poor risk | OS advantage not proven |

| CASTOR | NCT02136134 | Daratumumab, myeloma after at least 1 prior therapy | OS data not mature |

| CheckMate 037 | NCT01721746 | Nivolumab, unresectable or metastatic melanoma and disease progression following ipilimumab | OS advantage not proven |

| CheckMate 069 | NCT01927419 | Nivolumab and ipilimumab, BRAF V600 wild-type unresectable or metastatic melanoma | Exploratory analysis OS advantage not proven |

| CheckMate 214 | NCT02231749 | Nivolumab and ipilimumab, first-line intermediate or poor-risk RCC | Crossover error |

| CheckMate 238 | NCT02388906 | Nivolumab, adjuvant melanoma with lymph nodes | Crossover error |

| CLARINET | NCT00353496 | Lanreotide, unresectable or metastatic GEP-NETs, nonfunctional | OS advantage not proven Suboptimal control arm Crossover error |

| CLL14 | NCT02242942 | Venetoclax and obinutuzumab, previously untreated CLL with comorbidities | OS data not mature Suboptimal control arm |

| COLUMBUS | NCT01909453 | Encorafenib and binimetinib, metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E or V600K mutation | OS data not mature |

| COMPLEMENT 2 | NCT00824265 | Ofatumumab, relapsed CLL | OS advantage not proven Suboptimal control arm |

| DUO | NCT02004522 | Duvelisib, relapsed/refractory CLL or SLL after 2 prior therapies | OS data not mature Suboptimal control arm Crossover error |

| ECHELON-1 | NCT01712490 | Brentuximab vedotin, stage III or IV HL | OS advantage not proven—planned interim analysisa |

| EMBRACA | NCT01945775 | Talazoparib, germline BRCA-mutated ERBB2-negative metastatic breast cancer in patients who have been treated with chemotherapy | OS advantage not proven—planned interim analysisa Suboptimal control arm |

| ENGOT-OV16/NOVA | NCT01847274 | Niraparib, maintenance for recurrent ovarian cancer in CR or PR after platinum-based chemotherapy | OS data not mature |

| ET743-SAR-3007 | NCT01343277 | Trabectedin, unresectable or metastatic liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma | OS advantage not proven |

| ExteNET | NCT00878709 | Neratinib, adjuvant ERBB2-positive breast cancer | OS advantage not proven |

| GADOLIN | NCT01059630 | Obinutuzumab, follicular lymphoma in patients who relapsed after or are refractory to rituximab | Suboptimal control arm |

| GALLIUM | NCT01332968 | Obinutuzumab, previously untreated stage II bulky, III, or IV follicular lymphoma | OS advantage not proven |

| GOG-0213 | NCT00565851 | Bevacizumab, platinum-sensitive (>6 mo), recurrent ovarian cancer | OS advantage not proven |

| GOG-0218 | NCT00262847 | Bevacizumab, epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer | OS advantage not proven |

| IFM2005-02 | NCT00430365 | Lenalidomide, maintenance for myeloma following ASCT | OS advantage not proven |

| iLLUMINATE | NCT02264574 | Ibrutinib, treatment-naive CLL, in patients aged ≥65 y or <65 y with coexisting conditions | OS data not mature Suboptimal control arm |

| IMpassion130 | NCT02425891 | Atezolizumab, first-line metastatic TNBC | Suboptimal control arm |

| iNNOVATE | NCT02165397 | Ibrutinib, Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia | OS advantage not proven Suboptimal control arm |

| JAVELIN Renal 101 | NCT02684006 | Avelumab, first-line advanced RCC, with axitinib | OS data not mature |

| JGDG | NCT01185964 | Olaratumab, soft tissue sarcoma for which anthracycline is appropriate | Suboptimal control arm |

| KATHERINE | NCT01772472 | TDM-1, adjuvant therapy for ERBB2-positive early breast cancer in patients who previously received trastuzumab and taxane neoadjuvantly with residual disease | OS data not mature |

| KEYNOTE-006 | NCT01866319 | Pembrolizumab, unresectable or metastatic melanoma | Crossover error |

| KEYNOTE-042 | NCT02220894 | Pembrolizumab, first-line NSCLC (PD-L1 ≥1%) | Crossover error |

| KEYNOTE-045 | NCT02256436 | Pembrolizumab, metastatic urothelial carcinoma who progress on platinum therapy | Suboptimal control arm |

| KEYNOTE-054 | NCT02362594 | Pembrolizumab, adjuvant melanoma after complete resection | OS data not mature Suboptimal control arm |

| MAIA | NCT02252172 | Daratumumab, newly diagnosed multiple myeloma that are transplant ineligible | OS data not mature Suboptimal control arm Crossover error |

| METEOR | NCT01865747 | Cabozantinib, advanced RCC in following 1 line of therapy | Suboptimal control arm |

| MONALEESA-2 | NCT01958021 | Ribociclib, postmenopausal HR-positive, ERBB2-negative breast cancer, first line | OS data not mature |

| MONARCH 3 | NCT02246621 | Abemaciclib, postmenopausal HR-positive, ERBB2-negative breast cancer | OS data not mature |

| Motzer et al, 2015 | NCT01136733 | Lenvatinib plus everolimus, advanced RCC following 1 line of therapy | OS advantage not proven |

| MURANO | NCT02005471 | Venetoclax, CLL with or without 17p deletion, in patients who received at least 1 line of therapy | Suboptimal control arm |

| OCEANS | NCT00434642 | Bevacizumab, platinum-sensitive (>6 mo), recurrent ovarian cancer | OS advantage not proven |

| OlympiAD | NCT02000622 | Olaparib, germline BRCA-mutated ERBB2-negative metastatic breast cancer in patients who have been treated with chemotherapy | OS advantage not proven Suboptimal control arm |

| PALOMA-1 | NCT00721409 | Palbociclib, postmenopausal HR-positive, ERBB2-negative breast cancer | OS advantage not proven |

| PALOMA-2 | NCT01740427 | Palbociclib, postmenopausal HR-positive, ERBB2-negative breast cancer | OS data not mature |

| PANORAMA-1 | NCT01023308 | Panobinostat, myeloma after at least 2 lines of therapy | OS advantage not proven |

| POLLUX | NCT02076009 | Daratumumab, myeloma after at least 1 prior therapy | OS data not mature Suboptimal control arm |

| PROLONG | NCT01039376 | Ofatumumab, extended therapy (maintenance) in recurrent/progressive CLL in PR/CR | OS advantage not proven |

| PROSPER | NCT02003924 | Enzalutamide, nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | OS advantage not proven—planned interim analysisa Suboptimal control arm |

| RADIANT-4 | NCT01524783 | Everolimus, progressive, nonfunctional gastrointestinal and lung NET | OS data not mature Suboptimal control arm |

| RESONATE | NCT01578707 | Ibrutinib, previously treated CLL | Suboptimal control arm |

| RESONATE-2 | NCT01722487 | Ibrutinib, first-line CLL | Suboptimal control arm |

| RESPONSE | NCT01243944 | Ruxolitinib, polycythemia vera in patients who had inadequate response to hydroxyurea | OS not studied, but desirable Crossover error |

| SELECT | NCT01321554 | Lenvatinib, metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer | OS advantage not proven Crossover error |

| SOLAR-1 | NCT02437318 | Alpelisib, HR-positive, ERBB2-negative, PIK3CA-mutated metastatic breast cancer, postmenopausal women and men | OS data not mature |

| SOLO1 | NCT01844986 | Olaparib, first-line maintenance for BRCA-mutated ovarian cancer in CR or PR after platinum-based chemotherapy | OS advantage not proven—planned interim analysisa Crossover error |

| SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21 | NCT01874353 | Olaparib, maintenance for relapsed ovarian cancer in CR or PR after platinum-based chemotherapy | OS data not mature |

| SPARTAN | NCT01946204 | Apalutamide, nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | OS advantage c—second interim Suboptimal control arm Crossover error |

| S-TRAC | NCT00375674 | Sunitinib, adjuvant RCC | OS advantage not proven |

| Study 0761-010 | NCT01728805 | Mogamulizumab, relapsed or refractory mycosis fungoides or Sezary syndrome after at least 1 prior systemic therapy | OS advantage not proven Suboptimal control arm Crossover error |

| TOURMALINE-MM1 | NCT01564537 | Ixazomib, myeloma after at least 1 prior therapy | OS advantage not proven Suboptimal control arm |

Abbreviations: ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CR, complete response; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; GEP-NET, gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumor; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; HR, hormone receptor; NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer; OS, overall survival; pcALCL, primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; PR, partial response; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma; TDM-1, trastuzumab emtansine; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

Refers to specified analysis of OS. These may show an OS advantage in the future.

Discussion

Our results show that of 187 anticancer drug trials leading to 176 marketing authorizations by the FDA over a 5-year period, 125 (67%) had at least 1 of 4 limitations in design (control arm, crossover, single arm) and/or lack of OS benefit (including 1 noninferiority trial). Our findings raise important concerns.

Nonrandomized clinical trials constitute the basis for one-third of all marketing authorizations. Although results of nonrandomized clinical trials are markers of drug activity, many drugs approved on the basis of these trials exaggerate treatment efficacy when tested in RCTs.13,14 Furthermore, when evaluated by value scales (eg, the European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale, only one-third of single-arm trials were shown to meet the criteria for substantial clinical benefit.15,16 To balance the risk and benefit of early market authorization of investigational agents without proven superiority over standards of care, the accelerated approval pathway was developed by the FDA. Accelerated approval expedites the availability of potentially effective therapies with the requirement to conduct postapproval confirmatory trials. However, we found that approximately one-third of these approvals (21 of 64 [32%]) are regular approvals and not subject to confirmatory efficacy trials. This leaves substantial uncertainty as to their overall benefit over prevailing standards of care. Previous work estimated that only 20% of anticancer drugs receiving accelerated approval are shown to improve survival, although some studies remain ongoing.17

Surrogate end points were common, with 86 of 122 RCTs (70%) having a surrogate end point as the primary end point. Approvals for new drugs based on surrogate end points should be limited to specific circumstances where limited treatment options exist, the possible benefit is high, and the likelihood of harm is low. Overall survival, considered the criterion standard clinical end point, particularly for lethal conditions, was almost always assessed in RCTs (98%). However, approximately one-third (30%) of anticancer drug approvals based on RCTs failed to show a statistically significant improvement in OS. Approximately half of all trials (46%) had either unknown effects on OS or failed to show gains in OS. Our results show similar findings to previous reports, wherein two-thirds of cancer drugs were approved on the basis of a surrogate end point and half were reported to have unknown effects or failed to show gains in OS.2,18,19

Although crossover is often cited as a reason for failure to see an OS gain after an improvement in a surrogate end point, we found that only in the minority of clinical trials (17 of 122 [14%]) could the absence of an OS advantage be due to inappropriate crossover. This finding suggests that either the investigational agents are not effective in improving OS or that the trial was not powered to detect an OS benefit.20 Many of the trials that failed to show an OS benefit were of anticancer drugs used for treating relatively indolent malignant neoplasms for which postprogression therapy or crossover was prevalent (eg, ibrutinib plus rituximab vs placebo plus rituximab for Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia). Another group of approvals that failed to show an OS benefit were of maintenance therapies in which OS can be difficult to measure owing to the use of subsequent lines of therapy (eg, rucaparib maintenance therapy in recurrent ovarian cancer) (eTables 1 and 2 in the Supplement).

Suboptimal control arms in our study were similar to prior reports in this comprehensive data set that included multiple indications for the same agent (25% vs 17%, respectively).3 The use of a substandard control arm may result in a trial that is more likely to be positive (ie, meet its primary end point) but prevents the trial from addressing the clinically relevant question: Is this new drug better than the current standard of care?

Errors in use of crossover were estimated at approximately 14% of RCTs—that is, trials allowed crossover to the investigational agent without proven efficacy or FDA approval in subsequent lines of therapy or omitted crossover to drugs with established efficacy or FDA approval in subsequent lines of therapy. Allowing patients in the control arm to receive the investigational agent may result in diminution of any effect on OS21 and is often cited as a reason for cancer trials not demonstrating and OS benefit. In our analysis, only half of the errors in crossover were due to crossover to an unapproved intervention (ie, investigational agent without established efficacy in a latter line of therapy). The opposite error, prohibiting crossover to an approved intervention (ie, investigational agent with established efficacy in a latter line of therapy), may lead to an overestimation of the benefit seen with the investigational agent because patients in the control arm are deprived of an accepted salvage therapy. This type of error was seen in half of the cases in our analysis (ie, no protocol-specified crossover design despite it being more appropriate given that the intervention was an FDA-approved drug in the later-line setting).

The FDA has commented on the ethical considerations with regard to crossover and has been supportive of early crossover in RCTs when a surrogate primary end point (eg, progression-free survival, overall response rate) is met.22,23 In such trials, patients in the control arm would be allowed to cross over to the investigational agent after a prespecified analysis demonstrates efficacy in a surrogate (eg, response rate or tumor shrinkage). In our analysis, when a protocol amendment allowed crossover due to interim analysis meeting an efficacy end point, we conservatively considered such crossover appropriate. Yet we note that this strategy may limit the ability of a drug to demonstrate an improvement in OS (if one exists) or alternatively may limit the ability to demonstrate a decrease in survival (harm) that may be a late effect of the investigational agent that both arms of the trial will be exposed to. Finally, crossover is not associated with faster trial enrollment, as some hypothesize.24 Although multiple statistical methods have been developed to model OS in these situations, assuming crossover had not occurred, all such models rely on assumptions regarding the balance of a drug’s on-target and off-target effects, and none of these methods are without their own limitations.25

Limitations

Our analysis sought to evaluate the presence of clinically relevant limitations of interest in clinical trials leading to marketing authorizations over a 5-year period. Critically addressing limitations during the design of clinical trials can improve the quality of evidence on which we base anticancer drug approvals, decrease erroneous conclusions, and focus more on hard end points (eg, OS). Our findings are complementary to a 2019 analysis26 that evaluated risk of bias in RCTs supporting approvals in Europe between 2014 and 2016 using the Cochrane risk of bias tool, which assesses different domains than our study. The trial limitations we included in our analysis address questions faced by practicing oncologists.

The main limitation of our analysis is subjectivity in the assessment of acceptable standard of care and the appropriateness of the use of crossover. We attempted to limit subjectivity by individually and separately reviewing the guidelines and establishing consensus standard of care for each malignant neoplasm. Furthermore, whether crossover was specified in the protocol was not always reported in the article, especially when crossover was not allowed. In these cases, the protocol was reviewed, when available, and when no mention was found, lack of protocol-specified crossover was assumed. Postprogression therapy was not always reported in the article, nor the supplement, so non–protocol-specified crossover from the control arm to an agent similar to the investigational agent in the trial (eg, a programmed cell death 1 [PD-1] inhibitor) was not always captured. This made it difficult to interpret the data in light of real-world use of anticancer drugs. For example, in the OCEANS trial,27 crossover to bevacizumab on progression was not allowed, but 38% of patients who progressed in the control arm received bevacizumab off protocol. Finally, other important design flaws that may limit the validity of trial results were not captured in our limitations. For example, in the PACIFIC trial,28 standard imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography/computed tomography and brain magnetic resonance imaging for staging were not done prior to enrolling participants. This may have enriched the trial for patients with undiagnosed stage IV non–small cell lung cancer, some of whom received active therapy in the form of durvalumab while others received placebo. Finally, it is inevitable that others may disagree with our categorization, and we encourage further study.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that 67% of trials that led to FDA approval of anticancer agents had 1 or more limitations that include lack of randomization, lack of significant OS benefit, use of suboptimal control arm, and errors in the use of crossover. These limitations identify trials that do not address the clinically relevant question of whether patients will live longer or better lives if a novel agent is used over the current standard of care. As such, trial design and end point should be carefully addressed prior to enrollment to ensure that new anticancer drugs are superior to what most patients would receive in daily practice.

eTable 1. Clinical trials with suboptimal control arms

eTable 2. Clinical trials with crossover errors

References

- 1.Chen EY, Raghunathan V, Prasad V. An overview of cancer drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration based on the surrogate end point of response rate. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(7):915-921. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim C, Prasad V. Cancer drugs approved on the basis of a surrogate end point and subsequent overall survival: an analysis of 5 years of US Food and Drug Administration approvals. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1992-1994. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hilal T, Sonbol MB, Prasad V. Analysis of control arm quality in randomized clinical trials leading to anticancer drug approval by the US Food and Drug Administration. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(6):887-892. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad V. Double-crossed: why crossover in clinical trials may be distorting medical science. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(5):625-627. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haslam A, Prasad V. When is crossover desirable in cancer drug trials and when is it problematic? Ann Oncol. 2018;29(5):1079-1081. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prasad V, Berger VW. Hard-wired bias: how even double-blind, randomized controlled trials can be skewed from the start. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(9):1171-1175. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mok TSK, Wu Y-L, Kudaba I, et al. ; KEYNOTE-042 Investigators . Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1819-1830. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32409-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Food and Drug Administration Hematology/oncology (cancer) approvals and safety notifications. Accessed March 11, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/hematologyoncology-cancer-approvals-safety-notifications

- 9.US Food and Drug Administration Drugs@FDA: FDA-approved drugs. Accessed March 11, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/

- 10.Zinzani PL, Ribrag V, Moskowitz CH, et al. Safety and tolerability of pembrolizumab in patients with relapsed/refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2017;130(3):267-270. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-12-758383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang JC-H, Sequist LV, Geater SL, et al. Clinical activity of afatinib in patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer harbouring uncommon EGFR mutations: a combined post-hoc analysis of LUX-Lung 2, LUX-Lung 3, and LUX-Lung 6. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):830-838. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00026-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tap WD, Wagner AJ, Papai Z, et al. ANNOUNCE: a randomized, placebo (PBO)-controlled, double-blind, phase (Ph) III trial of doxorubicin (dox) + olaratumab versus dox + PBO in patients (pts) with advanced soft tissue sarcomas (STS) [abstract No. LBA3]. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(18)(suppl). doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.18_suppl.LBA3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zia MI, Siu LL, Pond GR, Chen EX. Comparison of outcomes of phase II studies and subsequent randomized control studies using identical chemotherapeutic regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(28):6982-6991. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gyawali B, D’Andrea E, Franklin JM, Kesselheim AS. Response rates and durations of response for biomarker-based cancer drugs in nonrandomized versus randomized trials. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(1):36-43. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.7345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vivot A, Jacot J, Zeitoun J-D, Ravaud P, Crequit P, Porcher R. Clinical benefit, price and approval characteristics of FDA-approved new drugs for treating advanced solid cancer, 2000-2015. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(5):1111-1116. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tibau A, Molto C, Borrell M, et al. Magnitude of clinical benefit of cancer drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration based on single-arm trials. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(11):1610-1611. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gyawali B, Hey SP, Kesselheim AS. Assessment of the clinical benefit of cancer drugs receiving accelerated approval. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(7):906-913. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou J, Vallejo J, Kluetz P, et al. Overview of oncology and hematology drug approvals at US Food and Drug Administration between 2008 and 2016. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(5):449-458. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zettler M, Basch E, Nabhan C. Surrogate end points and patient-reported outcomes for novel oncology drugs approved between 2011 and 2017. JAMA Oncol. 2019;(July). doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amir E, Seruga B, Kwong R, Tannock IF, Ocaña A. Poor correlation between progression-free and overall survival in modern clinical trials: are composite endpoints the answer? Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(3):385-388. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinstein GS, Levin B. Effect of crossover on the statistical power of randomized studies. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;48(4):490-495. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(10)66846-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Food and Drug Administration Remarks to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Policy Summit—06/25/2018. Accessed April 7, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/speeches-fda-officials/remarks-national-comprehensive-cancer-network-policy-summit-06252018

- 23.Kuznar W. A dynamic FDA has led to more rapid cancer drug development. Accessed April 7, 2020. http://oncpracticemanagement.com/issues/2018/february-2018-vol-8-no-2/1067-a-dynamic-fda-has-led-to-more-rapid-cancer-drug-development

- 24.Chen EY, Prasad V. Crossover is not associated with faster trial accrual. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(3):776-777. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watkins C, Huang X, Latimer N, Tang Y, Wright EJ. Adjusting overall survival for treatment switches: commonly used methods and practical application. Pharm Stat. 2013;12(6):348-357. doi: 10.1002/pst.1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naci H, Davis C, Savović J, et al. Design characteristics, risk of bias, and reporting of randomised controlled trials supporting approvals of cancer drugs by European Medicines Agency, 2014-16: cross sectional analysis. BMJ. 2019;366:l5221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aghajanian C, Blank SV, Goff BA, et al. OCEANS: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(17):2039-2045. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. ; PACIFIC Investigators . Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1919-1929. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Clinical trials with suboptimal control arms

eTable 2. Clinical trials with crossover errors