ABSTRACT

Objectives

A community of practice was described by Lave and Wenger as a mutual engagement using a shared repertoire of resources to attain a shared goal. This study explored the extent to which NHS workplaces function as communities of practice for core medical trainees.

Methods

All core medical trainees in one region were invited to a semi-structured interview. A framework was produced using communities of practice themes and a hybrid deductive-inductive method used for data analysis.

Results

NHS workplaces function as communities of practice by enabling engagement and by formation of mutual relationships. Joint enterprise was evidenced by multidisciplinary team working. Full participation was limited by service provision and short training rotations.

Conclusions

Trainee attendance in clinic and procedure lists should be facilitated. Trainees should be enabled to ‘act up’ as registrar. Flexibility is needed in jobs by allowing swaps between trainees and the facilitation of ‘taster weeks’.

KEYWORDS: Communities of practice, postgraduate medical training, educational theory

Introduction

There is currently a crisis within medical specialty recruitment, with many acute medical specialties filling fewer than 75% of specialty training year-3 (ST3) posts in recent years.1 This is partly driven by the perception of the medical registrar role as stressful and overburdened.2 Educational interventions such as mentoring / role models, broadening core medical training, teaching and information about medical specialties inform career choice.3,4 However, what is less clear is how the current pressured NHS workplaces support or undermine trainees' learning about the specialty and workplace.

This qualitative study examines core medical trainees' perceptions of NHS workplaces as communities of practice.

Communities of practice

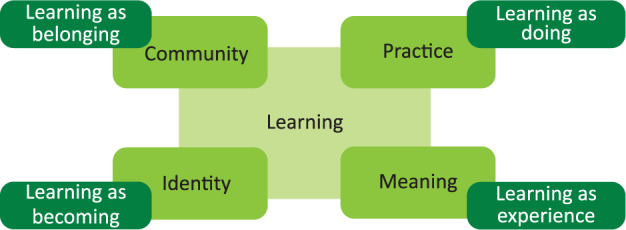

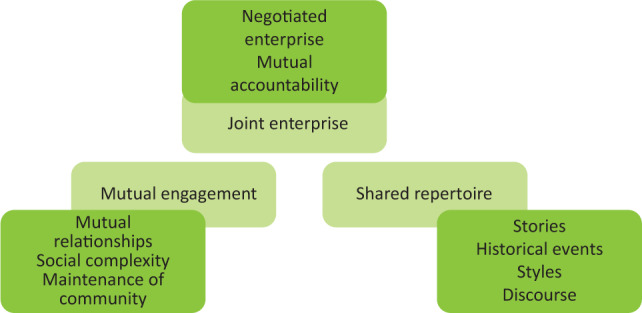

‘Communities of practice’ is a theory about how individuals learn (Fig 1).5 It states that learning happens through participation in a task and by becoming incrementally immersed in work and taking on greater responsibility; a form of apprenticeship. A community of practice is, in effect, a collection of individuals who come together to perform various tasks, but what makes this a community are three key attributes (Fig 2): working together (mutual engagement), a common goal (joint enterprise) and a collection of communal resources (shared repertoire).

Fig 1.

Components of a social theory of learning. Adapted from Wenger E. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Fig 2.

Characteristics of a community of practice. Adapted from Wenger E. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Meaningful learning within a community requires participants to engage. Concepts described by Wenger which contribute to mutual engagement include building relationships that support engagement, being essential to maintain the community.6 The second characteristic of communities of practice is joint enterprise, a shared goal negotiated by participants so that the community feels responsible for reaching that goal. The third characteristic is a shared repertoire - the creation of shared resources (eg shared language, shared history and ‘shortcuts’) that produce meaning for that community.

Communities of practice therefore allow the development of skills and knowledge, but they do more than this. They shape identity by focusing not just on acquiring skills and knowledge but also on becoming a certain person. Professional identity is defined as a combination of ‘attributes, beliefs, values, motives and experiences in terms of which people define themselves in a professional role’ which is of particular relevance to trainees planning their careers.7,8 The importance of communities of practice in the formation of a professional identity is recognised: ‘A “new apprenticeship” model...frames ward-based learning as a cultural act of participation leading to construction of professional identity.’9

Legitimate peripheral participation

Legitimate peripheral participation describes the process by which new members become part of the community of practice. Mastering knowledge and skills requires a movement towards full participation in the society and culture of that community. Legitimate peripheral participation also describes the relationships between newcomers to the group and old-timers.5 It is a key component of situated learning theory; learning occurs within a cultural context.

Communities of practice within the NHS

Spilg et al argue that recent changes to medical training, driven by the European Working Time Directive (EWTD), have eroded the formation of a professional identity by curtailing opportunities for immersion in communities of practice.10 Trainees have limited access to consultants and spend fewer hours at work in comparison to the pre-EWTD era. The narrow competencies required by the modern curriculum, and evaluated by workplace-based assessments, do not encourage mastery or full participation in the community of practice. Finally, the EWTD led to an increase in shift working, and therefore isolated doctors from each other's work and the outcomes of their own work, limiting recognition of a joint enterprise.

Methods

A qualitative methodological approach was used in this study, in particular, a method called interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA). An interpretivist paradigm assumes that there are multiple, equally valid realities, and that these are constructed in the minds of individuals (cf positivism). IPA is ‘a method for interpreting people's accounts of their own experiences’.11 It is an attempt to understand an individual's lived experience.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were used for data collection. These interviews use a topic guide of open-ended questions, but with the flexibility of pursuing additional topics as they are brought up in the discussion.12 The questions in the interviews were guided by concepts from communities of practice theory.

Setting and sample

The setting was a single UK region, comprising 12 hospital trusts and 17 hospitals. All core medical trainees (around 200 in the region) were invited to participate in semi-structured interviews via email sent out by the School of Medicine administration team. Participants were requested to have had some experience of their preferred specialty at a postgraduate level. A further two reminder emails were sent out by the administration team. Each postgraduate education centre in the trust also sent out emails locally.

Data analysis

Interviews were manually transcribed and then coded. Interviewees were sent a copy of the primary data analysis (transcript and codes) and invited to comment on the accuracy of the coding. Data analysis was via a hybrid inductive and deductive process. Deductive analysis is aimed at testing a theory, whereas inductive analysis makes conclusions based on the data gathered. Deductive coding used theoretical concepts from communities of practice to guide the analysis, whereas an inductive approach also allowed new issues to emerge.

Ethical approval

The study was reviewed by the University College London ethics screening board and was exempt from full ethical approval. Approval was gained from the core medical trainee training programme directors, and from the directors of medical education in each trust. Participation was on a voluntary basis; each participant was given an information sheet and gave informed consent.

Results

Five face-to-face and telephone interviews were conducted. The results are discussed in relation to the three components of communities of practice theory - mutual engagement, joint enterprise and shared repertoire (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of interview participants

| Participant number | Stage of training | Gender | Chosen specialty |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CT2 | Female | Neurology |

| 2 | CT1 | Male | Haematology |

| 3 | CT2 | Female | Haematology |

| 4 | CT1 | Female | Haematology |

| 5 | CT1 | Female | Microbiology/ID |

CT1 = core medical trainee year-1; CT2 = core medical trainee year-2; ID = infectious diseases.

Mutual engagement

Enabling engagement

The community allows trainees to become engaged with activities within the workplace, and to become a more central participant. This occurred in many ways - procedures, clinics, workplace-based assessments and access to consultants. Observing the registrar at work was an important part of learning about the specialty. However, formally ‘acting-up’ as registrar was not something often described; interview 1:

I don't think as [a senior house officer]...you have the same stresses. We didn't attend clinics...we didn't have the stress of having to carry the bleep, to have to deal with the...referrals.

In contrast, there were multiple examples of engagement not being enabled. Many jobs were felt to be service provision rather than training, and trainee attendance at clinic or procedure lists was not facilitated. Even when trainees did attend clinic, it was not helpful if they did not actively participate; interview 1:

Always more useful for me to see a patient first and then discuss...with the consultant rather than just sitting in clinic, boring as hell and nobody gets anything out of it.

Mutual relationships

Mutual relationships were described with respect to peers, other healthcare professionals and patients. The relationships within the community were a key influence on one participant; interview 5:

The most important things have been what kind of people you end up working with in your teams. I think [infectious diseases/microbiology], usually have quite a good relationship with their juniors...they're a sort of community.

Negative relationships were also described; interview 1:

The consultant, I found him quite intimidating actually; I didn't particularly enjoy working for him, he'd often make me feel quite stupid.

However, mutual relationships were not always apparent in the workplace. There was one trainee who described an absence of a mutual relationship; interview 1:

[Consultants] were hardly ever on the ward and many...who were there were not easily approachable.

This could limit the extent to which the NHS workplace is seen as a community of practice by trainees.

Joint enterprise

The second characteristic of a community of practice is the negotiation of a joint enterprise. It is the community's overarching goal as understood by its members. Patient-centred care and multidisciplinary working were two aspects discussed.

Patient-centred care

Trainees enjoyed the patient-centred nature of their chosen specialty; interview 2:

I appreciated...the amount of effort they were putting on...as a team, the specialist nurses, the doctors, regular nurses, everyone was very focused on each individual.

Patients often had chronic diseases, and developed specialist knowledge about their own condition, meaning that a collaborative relationship formed with healthcare professionals and shared decision-making took place.

One participant described how the team-work and collaborative decision-making influenced them; interview 3:

I'm probably making less independent decisions but...our ward rounds consist of at least two consultants...a lot of the time I am asking questions to the seniors...because the decisions are quite complex...we're offered the opportunity to give our opinions.

Multidisciplinary teamwork

Another participant appreciated the amount of teamwork that took place in their chosen specialty compared to others; interview 5:

The reg was there and ended up doing up some of the more important jobs...So talking to [intensive treatment unit], stuff like that. I quite liked that...it's nice they are still involved in their inpatients whereas...I just find a lot of specialties now don't even know who's on the ward.

However, there were also examples where joint enterprise via effective multidisciplinary working was not clear to members - due to ineffective multidisciplinary team meetings or lack of leadership; interview 1:

There was meant to be a brief [multidisciplinary team meeting] with social worker, [physiotherapist, occupational therapist, speech and language therapist]...doctors...It wasn't a very structured process, you need someone who is leading it...in neurology there wasn't a leader.

Shared repertoire

The pursuit of a joint enterprise creates resources for meeting the objective of the community and getting the job done. These resources included knowledge of specialist roles, learning from other learners, and boundaries.

Specialist roles

Part of participating within the community of practice involves becoming aware of the specialist roles within that workplace. One interviewee described her positive experiences of nurses with enhanced roles; interview 3:

There's...less hierarchy between the nursing staff and the doctors so the nursing staff know what their patients need, they know haematology very well and we work together...they can do things like patient group directives for antibiotics...it kind of takes the pressure off us.

Nurses able to perform procedures traditionally done by doctors can help meet the community's goal efficiently, and knowledge of these roles allows core medical trainees to become fuller participants within the community by knowing how to get things done quickly.

Learning from other learners

Knowledge dissemination is an important aspect of the shared repertoire, and educational meetings are also an important way to enhance mutual relationships. Participants learnt from other learners, but this tended not to be interdisciplinary. Learning from other learners did not always occur - one participant felt that his most important learning events came from managing patients when on-call, and from reflection thereafter; interview 2:

Most of the time, especially during night shifts, I was the most senior doctor...So when you're facing a difficult situation, that's when you learn so I would say I learned by experience, I learned by managing very difficult, complicated patients.

One of the ways in which a community of practice transmits its values and preferred behaviours is via role modelling. A situated learning theory emphasises the importance of social and situational context in learning. Newcomers to the group learn by modelling the behaviour of more established members of the community. Role models did influence specialty choice in some interviewees. There were also instances where undesirable attitudes and behaviours were modelled by members of the community; interview 1:

I think because the senior sort of consultants and registrars thought of it as a chore...we the [senior house officers] started to think of it as a chore.

Boundaries

There are also boundaries to sharing repertoires, particularly between communities. One participant described how they were denied experience of a particular specialty at undergraduate level, which acted to limit their awareness of it as a potential career; interview 3:

I didn't really think about haematology before I did the job because I don't think it's covered that well in in medical school...it obviously had a big influence doing the job, I don't think I would have known about it had I not done it.

Despite trainees feeling that their chosen specialty had a good relationship with other specialties, demonstrated by close working with radiologists and histopathologists, for example, they were aware of some negative opinions held by general medical specialties. There was also clear conflict between acute medical and other specialties; interview 3:

Sometimes people say ‘Oh, you don't have to do general medicine on call’ but maybe don't realise...the pressures of the lab and the pressures of being non-resident on-call.

Discussion

The participants in this study described many ways in which NHS workplaces function as communities of practice via mutual engagement, joint enterprise and shared repertoire.

Mutual engagement

Examples identified by participants included encouragement of clinic attendance, involvement with procedures and observing seniors. Dysfunctional relationships were occasionally described, but their presence does not necessarily demonstrate the lack of or failure of a community of practice.6

Trainees did not always experience mutual engagement within NHS workplaces. This was often due to service provision requirements. ‘Acting-up’ as registrars did not often take place. Solely observing their seniors did not necessarily enable the trainee to move from peripheral participation to a more central place in the community. As observed by Chaudhuri et al, observation of registrars solely in an acute environment (such as the ward or on-call) can lead to a skewed view of their day-to-day working.13

A further factor limiting participation was the short duration of placements, leading to difficulties in becoming involved with audit or research. These findings would correlate with those of Spilg et al in that the restriction of training necessitated by the EWTD has limited the amount of time that trainees spend with consultants, and that short placement duration limits full participation within the community of practice.10

Joint enterprise

Interviewees discussed examples of joint enterprise including patient-centred care and multidisciplinary team working. Much of the discussion was focused on other doctors and excluded other healthcare professionals. This has been discussed by Atwal et al in their study of nurses' perceptions of multidisciplinary teamwork.14 A dominance of medical power influenced interactions, and nurses feared being scapegoated if they dissented. The communities of practice theory has been criticised for ignoring how power plays a part in shaping relationships within a community.15

Shared repertoire

Examples of a shared repertoire included specialist roles, learning from other learners, and boundaries. Trainees discussed ways in which positive (and negative) attributes were modelled. The ideas associated with the concept of a shared repertoire were not discussed in detail, and it is not clear how apparent the community's shared language and routines were to the participants. It may be that there is already experience and familiarity with specialist medical language from previous medical jobs, for example.

Involvement in general medicine was a key factor in specialty choice. All participants had chosen specialties that did not contribute to the medical take. The experience of being a medical registrar has been discussed extensively in the literature.2 In this study, the theme of ‘boundaries’ highlights how trainees view participation in the general medical take, which compares poorly to their experience within their chosen specialty. It seems that the role of the medical registrar, and participation in the acute take, is still an important (negative) factor in specialty choice.

Strengths and limitations

This study is based on communities of practice theory and the methods chosen lend themselves well to the aims of the project. Study limitations include a small and fairly homogeneous sample, with three participants choosing the same specialty. The educational environment and community of practice is likely to be significantly different in a workplace with a specialist patient population versus a general medical ward. However, in the context of an IPA approach this is not necessarily a concern as it allows diverging views to be explored in detail. Nevertheless, it is important not to extrapolate the results to the wider population or attempt to generalise. There is likely to have been selection bias among the participants. Those volunteering to take part in interviews might be expected to be more motivated trainees who are doing well in their careers and are more secure in their specialty choice.

Recommendations

There is an argument that core medical trainee placements should be longer, although this would be difficult to align with the need for completion of all competencies within the current training programme. However, what would be useful to trainees, and potentially more feasible, is to allow for greater flexibility for both swapping rotations and for taster experiences of the specialty.

Trainees would value more clinic time to enable them to obtain a more representative and balanced view of the specialty and to allow legitimate peripheral participation to occur by playing a fuller role within the community.

There should be efforts made to teach trainees on the acute take to encourage them into general medical-related specialties.

Given that several participants had made their specialty choice at an undergraduate level, it would seem important to further explore the reasons for this, possibly in the form of a longitudinal study.

Conclusion

The results demonstrate key themes from communities of practice literature, with demonstrable engagement from trainees within the community. However, it has been the authors' experience, as well as that of the study participants, that service provision and short rotations limit full engagement within the community.

We had considered role modelling to be more important in careers decision making than did the participants, although the results would be consistent with the existing literature which suggests that role models are not particularly important in careers decision making.16 Role modelling is perhaps more important in development of clinical skills and in general professional identity as a doctor rather than specialty identity.

This study adds to existing literature by considering how core medical trainees perceive their workplaces as communities of practice.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the time given by the interview participants, without which this study would not have been possible. Thanks also go to the Health Education Kent, Surrey and Sussex (HEKSS) School of Medicine administration team, regional training programme directors and local directors of medical education for their support with this project.

Funding

This work formed part of the requirements for Carolyn Amery's MSc in Medical Education with University College London / Royal College of Physicians, for which they received a bursary of £1,000 from HEKSS. HEKSS did not contribute to the study concept or design.

References

- 1.Health Education England Physician ST3 recruitment. HEE, 2019. www.st3recruitment.org.uk/specialties/overview [Accessed 25 January 2019].

- 2.Chaudhuri E, Mason N, Logan S, Newbery N, Goddard AF. The medical registrar: empowering the unsung heroes of patient care. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright S, Wong A, Newill C. The impact of role models on medical students. J Gen Intern Med 1997;12:53–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horn L, Tzanetos K, Thorpe K, Straus SE. Factors associated with the subspecialty choices of internal medicine residents in Canada. BMC Med Educ 2008;8:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wenger E. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schein EH. Career dynamics. Matching individual and organisational needs. Reading: Addison-Wesley, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibarra H. Provisional selves: experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Administrative Science Quarterly 1999;44:764–91. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleakley A. Pre-registration house officers and ward-based learning: ‘new apprenticeship model’ model. Med Educ 2002;36:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spilg E, Siebert S, Martin G. A social learning perspective on the development of doctors in the National Health Service. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:1617–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffin A, May V. Narrative analysis and interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: Seale C. (ed), Researching society and culture, 3rd edn London: Sage Publications, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dicicco-Bloom B, Crabtree BF. The qualitative research interview. Med Educ 2006;40:314–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaudhuri E, Mason N, Newbery N, Goddard AF. Career choices of junior doctors: is the physician an endangered species? Clin Med 2013;13:330–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atwal A, Caldwell K. Nurses' perceptions of multidisciplinary team work in acute health-care. Int J Nurs Pract 2006;12:359–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts J. Limits to communities of practice. Journal of Management Studies 2006;43:623–39. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burack JH, Irby DM, Carline JD, Ambrozy DM, Ellsbury KE, Stritter FT. A study of medical students' specialty-choice pathways: trying on possible selves. Acad Med 1997;72:534–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]