Abstract

During the course of novel coronavirus pandemic ,Shariati hospital in Tehran , as a tertiary center in both orthopedic trauma and COVID-19 , we detected 7 cases with definite diagnosis of COVID-19 and concomitant emergent orthopedic problem.This paper represents considerations and special issues in managing and decision making in these patients.

Key Words: Coronavirus, Fracture, Orthopedic trauma

Introduction

Novel coronavirus infection is highly communicable with a high rate attack and can cause significant morbidity or even mortality, especially among vulnerable patients(1). After the first reports of disease in Iran, our crisis management committee in Shariati hospital, Tehran, as a tertiary center in both orthopedic trauma management as well as COVID-19, made some decisions and implemented a series of actions to manage the crises.

According to infection control guidelines, we postponed all elective activities in the orthopedic department,but, as non-elective programs are unpredictable and inevitable, we hadto play a role in managing both COVID-19 and orthopedics trauma cases. While the disease can be asymptomatic during its entirecourse or at least in the incubation phase(2),and considering itshigh prevalence in our region, we ran an evaluative program for orthopedic patients based onhistory, physical examination, and imaging studies including plain chest X-ray or chest CT scan according to the clinical status and degree of suspicion(3, 4).

Since the beginning of the outbreak in our region to this time,194 patients with orthopedic emergent problems have been admitted in our department.We detected seven cases of COVID-19through screening which were confirmed by PCR test during the course of management.

This manuscriptis a report of special conditions and considerations related to decision making, planning, and managing COVID-19 patients during the outbreak. In the first couple of patients as the prevalence of COVID-19 was low, we were less prepared but gradually promoted to a higher level of preparedness and flexibility in managing the situation by developing some strategies and changes in management protocols. Cases are presented in the paper by regard to the date of admission which is in accordance with the progression of the COVID crisis.

Case presentation

Case 1

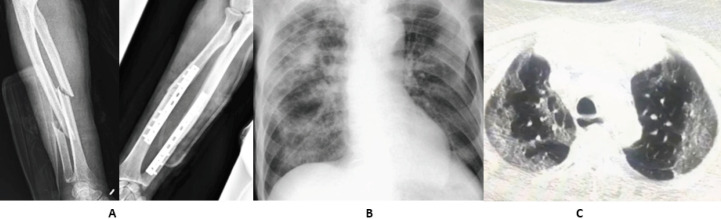

A 65 years old homeless man withnomedical history was admitted with right radioulnar fracture. He had a simple fall in about seven days before the admission and after exacerbation of pain and swelling, without any other symptoms, presented to the emergency department (ED). Fixation was done on the same day as the first visit. Surgery was uneventful and done under general anesthesia. The workup for COVID-19day began after the surgery due to low-grade fever, oxygen desaturation and cough.As the first step the patient was moved to an isolated room. Chest X-ray and CT scan as well asRT-PCR test was performed. Chest X-ray and CT scan showed reticulation and consolidation in addition to ground glass view which was consistent with the findings of COVID-19(5). Laboratory examinations revealed leukocytosis and elevation in both ESR and CRP. The RT-PCR test was positive and the patient was moved to the respiratory care unit for further treatment. He was discharged after 10 days with good general condition and no residual symptoms [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

A:Preoperative and early post operative X-rays of radioulnar fracture fixed by DCP plate.B&C:Plain chest X-ray and CT scan revealed reticulation and paranchymal changes

Hewas the first case in the orthopedic department and since the patient was completely asymptomatic before the surgery, the level of protection for medical staff was low and the patient was in close contact with other patients which led to more infection exposure in other people. So, it was an alarmand made us vigilant about the screening for COVID-19, following self-protection guidelines for medical staff, and isolation of patients to prevent the spreading during the course of treatment.

Case 2

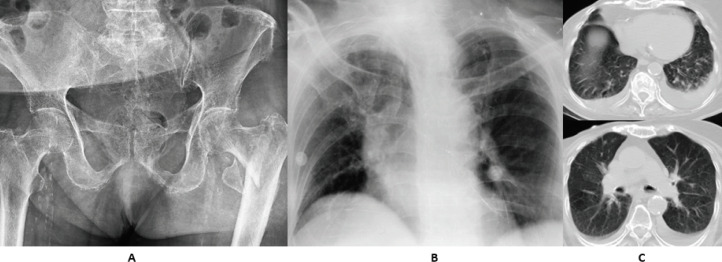

A 91 years old female was presented to us with left intertrochanteric fracture following a simple fall. She reported a history of hypertension, diabetes, and a completely cured breast cancer about six years ago. Since she had a cough and severe progressive shortness of breath during the last four days before admission, we obtained plain chest X-ray and CT scan in addition to laboratory tests. Radiographic findings were not pathognomonic for COVID-19 butlaboratory exams revealed elevated ESR, CRP, and leukocyte count. Since the RT-PCR test was positive and clinical feature was indicative, respiratory care applied immediately and the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) due to low oxygen saturation.

Considering the medical history, pulmonary condition, patient demand, previous low level of activity and pandemic conditionthathad altered our threshold for treatment to a lower level, conservative treatment with T-cast and bed rest was implanted [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Pelvic AP X-ray with left intertrochanteric fracture B: Plain chest X-ray revealed dirty chest in addition to atelectatic change C: Chest CT scan demonstrated bilateral pleural effusion with some degrees of parenchymal fibrosis due old radiotherapy

The patientshowed good general condition and progressive decrease in hip painat virtual follow-upafter three weeks. She was out of bed using a wheelchair. Treatment of viral pneumonia was as an inpatient for ten days and then continued for two weeks at home without any complication.

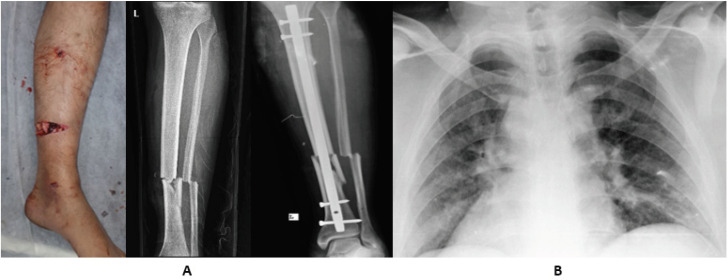

Case 3

A 39 years old man with left tibia and fibula shaft open fracture caused by a motor to car accident was brought to our ED by emergency medicine service. Fixation was done without any complication using intramedullary nailing technique under spinal anesthesia and with the use of complete protective personal equipment (PPE). The patient hadno clinical signs and symptoms of COVID pneumonia and preoperative chest X-ray and laboratory data were normal. About 12 hours after surgery patient demonstrated fever and cough with decreasein blood oxygen saturation to about 80%. Chest X-ray findings were not diagnostic, but, according to the highly suspicious clinical and laboratory features, an infectious medicine specialist advised to run a PCR andthe test was positive.

After isolation in the respiratory care unit and initial management including supplementary oxygen therapy and treatment for COVID pneumonia with oral Hydroxychloroquine and combination of Lopinavir and Ritonavir, the patient was stabilized. Early rehabilitation with a touchdown weight-bearing was done and he was discharged symptom-free after eight days [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

A: Photography and plain X-ray of open fracture in left tibiofibular shaft fracture, preoperative and postoperative B:plain chest X-ray wich was not diagnostic for COVID-19

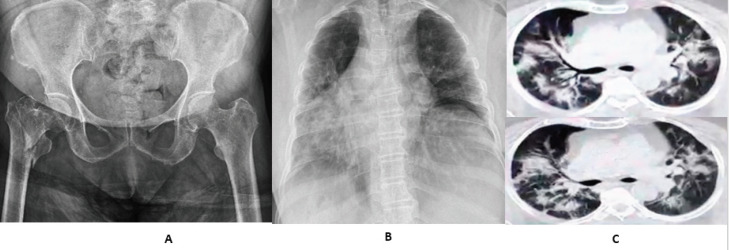

Case 4

A 72 years old female with a past medical history of diabetes and strokewas presented to our orthopedic emergency with right side intertrochanteric fracture after falling down. At the time of admission, she has respiratory distress and high-grade fever which was developed from the day before. Chest X-ray and CT scan revealed bilateral parenchymal involvement and ground glass view which was diagnostic for coronavirus infection. In addition, despite severe lymphopenia,extremely high levels of ESR and CRP and elevated leukocyte countwere all in favor of coronavirus infection [Figure 4].

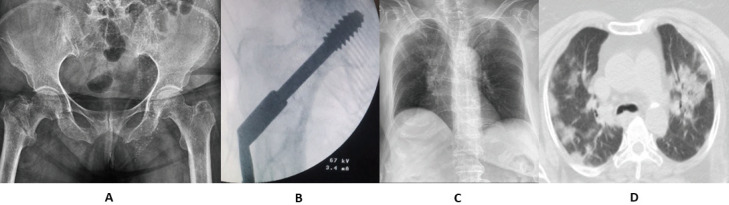

Figure 4.

A: Pelvic AP X-ray with right intertrochanteric fracture, B:plain chest X-ray with bilateral consolidation and ground glass view, C:Chest CT scan demonstrates paranchymal involvment with ground glass view in favore of COVID-19 pneumonia

Nonoperative treatment with T-cast was done for hip fracture with full protection. To prevent any exposure to other orthopedic patients and staff, she was directly transported to the respiratory intensive care unit (RICU). As it was predictable the PCR test was positive. Unfortunately, after intubation and mechanical ventilation in addition to the routine pharmacological treatment she was expired due to respiratory failure after two days.

Case 5

An 86 years old female without any medical history was admitted to ED due to an intertrochanteric fracture in the right hip. On initial screening, the positive findings were cough and fever from 5 days ago, but, the general condition was good and there was no oxygen desaturation. Chest X-ray was near normal but chest CT scan and PCR test both were positive for COVID-19. After consultation with the pulmonologist and anesthesiologist, the patient was prepared for surgery on the second day. The decision for surgical treatment was in accordance with good general and cardiopulmonary conditions and a high level of previous activity. The fracture was fixed with Dynamic Hip Screw (DHS) under spinal anesthesia and the operation time was about 60 minutes. Surgery was done by a senior experienced surgeon to minimize the operation time and intraoperative bleeding. The surgeon, assistants, and all other staff including the anesthesiology team were protected with an N95 face mask, antiviral hood and guan, and latex antiviral gloves. The number of people in the operation room was limited to minimize the exposure [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

A&B : Preoperative and intraoperative X-rays of right intertrochantric fracture fixed by DHS. C&D: Chest X-ray and CT scan which were positive for COVID-19 infection

The patient was moved to RICU after the surgery. She was under treatment for COVID with supplementary oxygen therapy and pharmacological agents. Postoperative rehabilitation ran as routine with non-weight bearing mobilization. She was discharged after 9 days and no orthopedic complications and pulmonary symptoms were seen at follow up visits.

Case 6

A 19 years old man with blunt chest trauma, bilateral calcaneal fracture, and right-side distal radius fracture following a fall from a height of 4 meters was presented to ED. No evidence of COVID-19 infection was detected during the primary survey and screening. The initial Chest X-ray was normal, but later, during work-up for high energy trauma, a chest CT scan revealed parenchymal abnormal changes and findings in favor of both COVID pneumonia and lung contusion.Elevated inflammatory markers and normal leukocyte count were positive findings. The result of online teleconsultation with a multidisciplinary team (including pulmonologist, radiologist, general surgeon, and infectious disease specialist) was that coronavirus infection is the most probable reason for radiologic changes. We ran a PCR test for coronavirus and after 12 hours the result pronounced as positive. During this time, he was under observation in isolation for any change in condition. Since the patient was asymptomatic there was no indication for in-hospital care for Coronavirus infection.

Bilateral calcaneal fracture was treated non-operatively with non-weight bearing mobilization and simple bandage. Although the distal radius fracture was intraarticular and partially displaced and surgical fixation was rationale, it was treated non operatively with a short arm cast after clear explanation to the patient and his family,considering the crisis, positive COVID PCR test,and risk of infection spread [Figures 6; 7].

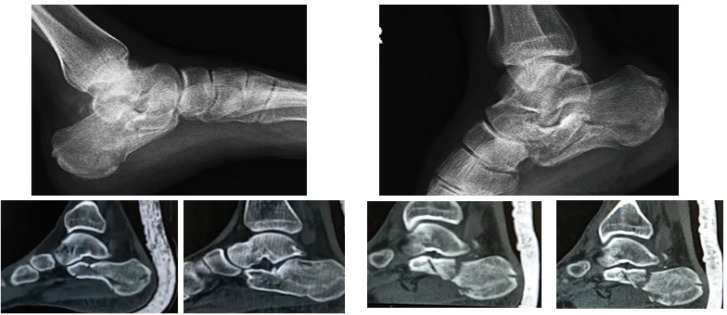

Figure 6.

Plain X-ray and sagital recostructed CT scan of both left (A) and right (B) calcaneal fracture

Figure 7.

AP and Lateral wrist X-rays demonstrate minimaly displaced distal radius fracture before (A) and after (B) casting

The patient was discharged with a strong recommendation for close follow up. At the first follow up visit no secondary displacement was seen neither in distal radius nor calcaneal fractures. The pain had decreased significantly and the general condition was good.

Case 7

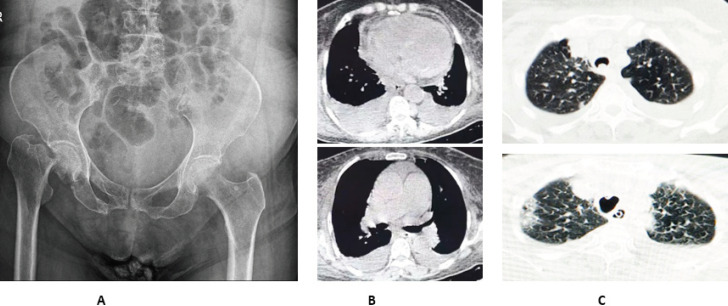

A 75 years old female with a past history of bladder cancer and renal metastasis was admitted with a right femoral neck fracture. She had massive hematuria and dyspnea which were consistent with renal and probable pulmonary metastasis. Fever and cough were not present and the oxygen saturation was normal. As expected,the inflammatory markers and leukocyte count were both elevated probably due to the active cancer. For additional workup, the patient underwent a chest CT scan. Bilateral pleural effusion, cardiomegaly, and pericardial effusionwere reported without nofinding of COVID pneumonia. During the optimization for surgery, she developed oxygen desaturation and surprisingly, thenew chest CT scanwas positive for COVID infection 24 hours after the first one [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

A: Femoral neck fracture in right side B:Initial chest CT scan demostrates bilateral pleural and pericardial effusion C:Comparison between iInitial CT scan (above) and second one (below)

Routine care for Coronavirus infection was established. Nonoperative treatment with T-cast implantation was done and the patient was transferredto RICU. On the next day and following exacerbation of respiratory distress in addition to severe anemia despite intubation and blood transfusion, the patient was expired. We had a delay in the PCR test result due to some technical problemsand the positive result came back after she was expired.

Cases summary

Summary of patients’ Demographic, clinical and management data is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and summarized information of management of patients

|

COVID

severity |

Fracture

Treatment |

CRP | ESR |

COVID presentation

At time of diagnosis |

Mechanism of injury | Fracture | Gender | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient treatment | ORIF | 84 | 45 | Fever & Cough Oxygen Desaturation |

Simple fall | Forearm Fx | Male | 65 | Case1 |

| Inpatient treatment | Non operative | 39 | 42 | Cough Sortness of breath |

Simple fall | Intertrochantric Fx | Female | 91 | Case2 |

| Inpatient treatment | ORIF | 43 | 36 | Fever & Cough Oxygen Desaturation |

Motor to Car accident | Tibia and ficular shaft Fx | Male | 39 | Case3 |

| Expired | Non operative | 79 | 51 | Fever and Respiratory distress | Simple fall | Intertrochantric Fx | Male | 72 | Case4 |

| Inpatient treatment | ORIF | 69 | 43 | Fever & Cough | Simple fall | Intertrochantric Fx | Female | 86 | Case5 |

| Outpatient Treatment | Non operative | 53 | 39 | Asymptomatic | Falling from height | Bilateral Calcaneal Fx Distal Radius Fx |

Male | 19 | Case6 |

| Expired | Non operative | 91 | 74 | Oxygen Desaturation | Simple fall | Femoral neck Fx | Female | 75 | Case7 |

Discussion

During an outbreak like what is happening now throughout the world, according to crisis management principles, all the health care systems should be focused on managing the situation and making preparedness in face of crises(6);but,as orthopedic emergencies, especially fractures, are inevitable, all orthopedic surgeons should be prepared for managing emergent cases during thecrisis.

As presented before, four of these seven cases had fractures in proximal femur due to low energy falling. Since fatigue and generalized weakness are common symptoms in patients with COVID-19(7), it can be assumed as a precipitating factor for falling down and subsequent hip fractures, especially in geriatric population. Furthermore,considering the issues like comorbidities, higher need for ICU admission and blood transfusion, and longer hospital stay in these cohort, it seems that management of this group during the crisis needs more detailed evaluation and the plan must incorporateall these factors. In our cases a mortality rate of 50 percent was seen among patients with coronavirus infection and hip fracture, so,for decision making in these cases, non-operative treatment is recommended.

Since the disease can be asymptomatic, like case one, especially during the incubation period (8), it seems rational to presume all patients who need orthopedic care and visit as a positive one. We strongly recommend the use of complete PPE, especially during the intubation or operation time(9), and isolation in case of need to inpatient care, even in asymptomatic patients. Furthermore, considering the limits in the availability of RT-PCR test, especially in developing countries, and also the high sensitivity and specificity of chest CT scan in diagnosis(10), implementation of a screening system, based on the clinical and radiological assessment, for asymptomatic patients who need surgical treatment seems to be necessary. Besides, it should be kept in mind that chest X-ray could be normal even in cases with moderate to severe pneumonia (11), as what happened in case number three. In our practice, the initial evaluation with focused history taking, physical examination, plain chest X-ray and laboratory study with CBC, ESR, and quantitative CRP was routine for all inpatient cases. Incase of any positive findings, a chest CT scan and PCR test were the next steps, depending on the level of suspicion.

Conservative and non-operative treatments for orthopedic problems, specifically fractures, can be used with a lower thresholdin critical circumstances like a pandemic. Indications for both surgical and non-surgical treatments and the strategies for decision making should be flexible. Dynamicity in planning and treatment selection is the most important rule(12). Any decision-making must bein accordanceto factors including general condition and severity of coronavirus infection in a patient, risk of surgery for both the patient and staff in positive cases, and risk of in-hospital contamination with the virus in those orthopedic patients who have not been infected yet.

On the other hand, it could be a promising point that in cases with mild to moderate infection or those whoseacute and fulminant phase is passed, like the case number five, surgical treatment with proper optimization and intraoperative self-protection is a possible safe option.

References

- 1.COVID C, Team R. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343–6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu Z, Song C, Xu C, Jin G, Chen Y, Xu X, Ma H, Chen W, Lin Y, Zheng Y, Wang J. Clinical characteristics of 24 asymptomatic infections with COVID-19 screened among close contacts in Nanjing, China. Science China Life Sciences. 2020;4:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1661-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang Y, Zhang H, Xie J, Lin M, Ying L, Pang P, Ji W. Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology. 2020;19:200432. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gostic K, Gomez AC, Mummah RO, Kucharski AJ, Lloyd-Smith JO. Estimated effectiveness of symptom and risk screening to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Elife. 2020:9. doi: 10.7554/eLife.55570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon SH, Lee KH, Kim JY, Lee YK, Ko H, Kim KH, Park CM, Kim YH. Chest radiographic and CT findings of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): analysis of nine patients treated in Korea. Korean journal of radiology. 2020;21(4):494–500. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toner E, Waldhorn R, Maldin B, Borio L, Nuzzo JB, Lam C, Franco C, Henderson DA, Inglesby TV, O’Toole T. Hospital preparedness for pandemic influenza. biosecurity and bioterrorism: biodefense strategy, practice, and science. 2006;1(2):207–17. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2006.4.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu YH, Dong JH, An WM, Lv XY, Yin XP, Zhang JZ, Dong L, Ma X, Zhang HJ, Gao BL. Clinical and computed tomographic imaging features of novel coronavirus pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Infection. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishiura H, Kobayashi T, Miyama T, Suzuki A, Jung S, Hayashi K, Kinoshita R, Yang Y, Yuan B, Akhmetzhanov AR, Linton NM. Estimation of the asymptomatic ratio of novel coronavirus infections (COVID-19) medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong KC, Leung KS, Hui M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in a geriatric patient with a hip fracture: a case report. JBJS. 2003;85(7):1339–42. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200307000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Xia L. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Role of chest CT in diagnosis and management. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2020;21:1–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hosseiny M, Kooraki S, Gholamrezanezhad A, Reddy S, Myers L. Radiology perspective of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): lessons from severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2020;28:1. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong J, Goh QY, Tan Z, Lie SA, Tay YC, Ng SY, Soh CR. Preparing for a COVID-19 pandemic: a review of operating room outbreak response measures in a large tertiary hospital in Singapore. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie. 2020;11:1. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01620-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]