Abstract

The COVID-19 disease is rapidly spreading around the world, affecting many countries and their healthcare systems. Like many other countries, Iran is struggling with the current situation. In this article, we aim to share our perspectives on confronting obstacles mentioned above using appropriate hospital protocols during the COVID-19 crisis.

We investigated and compared the number of referred patients to the emergency room, elective, and emergent orthopedic operations in our hospital, along with a number of residents and faculty participants in the morning reports and virtual classes before and after the outbreak of COVID-19 in our hospital.

The number of referred patients to the emergency room was significantly reduced; the number of orthopedic operations was also decreased to almost zero in March 2020. Meanwhile, we managed to dismiss our residents and reduce the number of in-hospital morning reports and conferences. Instead, we designed virtual classes, and the number of participants in our virtual classes grew to almost two-third of the whole participant. We also managed to fortify our virtual office system to reduce the number of in-hospital visits.

Since our hospital had become a leading center for the treatment of COVID-19 patients, and the number of referred trauma patients, elective, and trauma operations, along with educational activities, was reduced. There was also a significant concern about the management of elective, trauma, and post-operative patients in this era. Orthopedic faculty members needed to react to the current situation cautiously. We were able to manage the situation with consideration of our educational path, along with the management of personal protective equipment (PPE), and the use of communication technologies and specific protocols to overcome the obstacles mentioned above. Yet involved our staff and

With orthopedic faculties active involvement at in-hospital activitie and establishment of hospital protocols considering technological facilities and WHO guidelines, we can improve education, management of PPE, and both orthopedic elective and trauma patients.

Key Words: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Education, Orthopedics, Personal protective equipment, Telemedicine

Introduction

On 31 December 2019, Chinese health authorities announced that a novel coronavirus, an uninvited guest who is now known as SARS-Cov-2 causing COVID-19 disease, has entered the human society and is spreading in an alarming pace; Soon this disease was recognized as a pandemic by WHO (1). The number of affected patients grew shockingly as the reports showed by 18 March 2020, there were 193,475 confirmed cases and 7,864 deaths worldwide. In less than ten days, the total number of confirmed cases grew up to 552,589 and 25,042 deaths due to COVID-19 were reported all around the planet, and the numbers are still growing at a higher pace every day (2). Rampaging all around the globe, the disease took many governments by surprise. Soon, there was a shortage of standard protective equipment for health care providers and their people. The fact that the virus can survive several hours on a surface and it can be transmitted through droplets and knowing that it can become airborne in certain situations makes it very dangerous and raises many concerns in the general population and mostly among medical staff (3). By the nature of its geographical closeness to China and ongoing trade and transport between Iran and China, the disease spread in Iran rapidly. On 18 February, Iran’s government recognized the epidemic of COVID-19, which soon affected medical practice in the whole country.

What happened in our hospital?

In this critical situation affecting both patients and medical staff, there were multiple concerns that needed to be addressed. Our orthopedic department is founded in a general hospital, Imam Khomeini Hospital Complex (IKHC), the largest hospital in the country with more than 1200 beds and most specialties and subspecialties. Our department, as a referral center in the country, covers all subspecialties in the field of orthopedic surgery procedures, including arthroplasty, tumor, spine, sports, shoulder, foot and ankle, and hand surgery. We also have a devoted trauma section for orthopedic trauma. We perform approximately up to 460 orthopedic surgical procedures each month in our particular orthopedic room (OR). By the time of official recognition of the primary cases of COVID-19 in Qom city (the seventh largest city in Iran), our hospital became one of the major centers for treating COVID-19 patients. A separate outdoor respiratory triage was designed and used in order to protect non-COVID-19 patients who referred to the emergency department. A massive number of patients came to the respiratory triage. So far, 16000 patients have been visited, and 1600 were admitted to the hospital in a month. One hundred patients were admitted to the ICU; half of them were eventually intubated. Our orthopedic department leadership team was well aware of the vast amount of workload on the hospital. They decided not to perform elective orthopedic procedures, so they can be able to dedicate the staff, interns, and residents for cooperating with the corona team along with the hospital policies and plans. At that time, all orthopedic related activities at our department were locked.

Our response to the disaster needed to be quick and futuristic while covering all concerns simultaneously; For this reason, we decided to face the problem from multiple aspects. After categorizing it, we met the obstacles by using the knowledge of the experts and previous experience from our colleagues all around the globe and applying them considering our facilities and infrastructure.

Knowing the fact that there may be many new obstacles that we will encounter during this combat against one of the most insidious ferocious diseases of all time, in this article we try to share our point of view in approaching to this situation in our hospital.

Management of urgent orthopedic cases and the orthopedic workforce

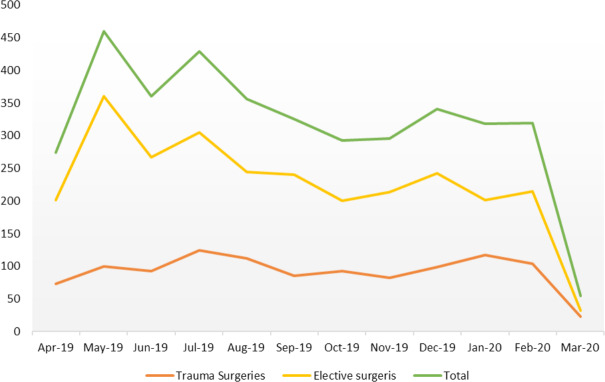

Due to the fact that our hospital had become one of the leading centers for referred COVID-19 cases in the metropolis of Tehran, our hospital, along with Emergency Medical Service authorities, decided not to admit trauma patients in this hospital. So most of the patients were referred to other hospitals specialized for orthopedic patients only. As a result, the number of referring patients to our Emergency Medicine Department was significantly reduced [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Number of Performed Orthopedic Surgeries Between April 2019 and March 2020

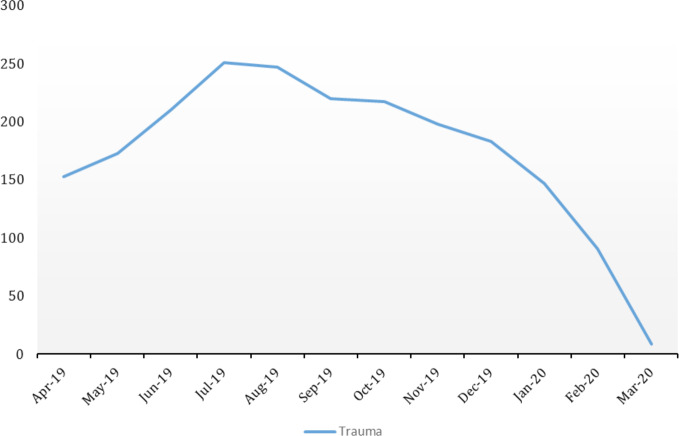

The next step was to immediately dismiss orthopedic interns to work as a reserved force for coronavirus clinics. Orthopedic resident shifts were reduced, and they were asked to help the corona treatment team instead of staying in the emergency room (ER). Simultaneously, they could participate as on-call orthopedic residents in their hospital shifts. Consequently, the number of orthopedic patients referred to ER were reduced to almost no patient at all [Figure 2]. Trauma operations were reduced from a mean of 98 per month to three in late February and March [Figure 1].

Figure 2.

Number of Orthopedic Patients Referred to the Emergency Room Between April 2019 and March 2020

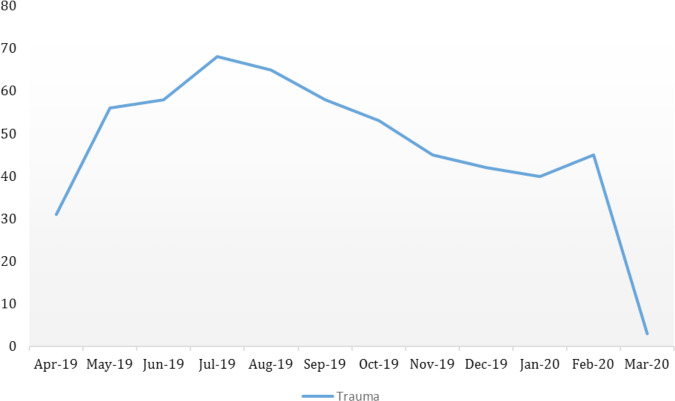

The only routine ongoing orthopedic operations were necessary amputations in diabetic foot patients and arthrotomy in patients with septic arthritis. These types of surgeries were reduced by 90% since the time of crisis [Figure 3]. One of the reasons can be the fearsome situation that patients with serious diseases find themselves in it, and they prefer to stay at home rather than being treated in a hospital filled with COVID-19 patients.

Figure 3.

Number of Performed Orthopedic Surgeries in the Emergency Operation Room Between April 2019 and March 2020

Although the number of urgent operations was reduced, there are always many concerns about orthopedic complications in patients with definite, suspected, or even symptomless COVID-19 disease, which need to be addressed. The challenge between the hospital deputy of treatment and surgeons in not admitting elective or even less urgent orthopedic cases in the time of the COVID-19 crisis remains a matter of debate in many centers around the world. The early experience of our colleagues in Singapore was to cancel and postpone their elective and non-urgent procedures that need admission for more than 23 hours (4). Still, they allowed all surgeries that required less than 23 hours of access. The protocol in our department was to postpone all non-urgent surgical operations in the time of the COVID-19 crisis as much as possible to prevent the nosocomial transmission of the disease, especially to elderly patients (5).

Changes in the approach to elective patient management

We acknowledge the fact that COVID-19 is now a pandemic, and most of the financial and human resources of the healthcare system should be allocated to prevent the disease from spreading and also the treatment of affected patients. To achieve these goals, we had to limit the number of orthopedic surgeries in all elective fields. Our rapid response was to discharge the already admitted patients from the orthopedic ward. The main clinical features at the onset of the disease in Wuhan patients were described (6). Still, reports were coming from China warned us that even asymptomatic patients could have a positive Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) test and can infect others (7-9). Knowing this fact and acting accordingly can significantly reduce the risk of infecting patients and healthcare providers as both groups could be silent carriers. This issue, along with other concerns such as shortage of anesthesiologists as they are currently fighting on different fronts in COVID-19 crisis and are inevitably withdrawn from elective surgery. Besides, hospital policies dictated that the number of beds used for orthopedic patients had to be reduced to dedicate beds and personnel to the new COVID-19 wards. Finally, we had to be sure not to infect elective patients with nosocomial COVID-19. Therefore, the number of elective surgeries in our operating room was reduced from 226 per month (mean) to zero in late February and March to protect our patients and staff from the active disease outbreak [Figure 1].

In the time of epidemic and crisis we contacted our patients via phone calls and recommended them to postpone their elective surgeries such as arthroplasty and spinal deformities or stenosis; still, there is a big concern about tumor patients who may have finished their chemotherapy or biopsy. They may need further treatment steps to benefit the most from their treatment plan.

Establishing telemedicine in an unprepared society

It is important for all orthopedic surgeons to stay aware of their patients’ health condition. Telemedicine was introduced to the world some years ago and physicians have been using it more or less around the world (10). In the time of the COVID-19 epidemic, our hospitals created a system in which all patients who underwent surgery within the past three months were notified via a short message text on their phones. The message asked them to contact their orthopedic surgeon to ask any questions or discuss the possible problems. Our protocol was to encourage using telemedicine by any means in all faculty members. The main objective of this telecommunication was to ensure the patients stay at their homes to lower the possibility of asymptomatic or affected COVID-19 patients to spread the disease in the community. Many orthopedic patients and surgeons are in their old ages. The condition has a more fatality rate in the older population (11). We aimed to lower the risk of exposing this group of patients as well. The telecommunication mentioned above, the Virtual Office System (VOS), was designed in a way that post-operative patients of each surgeon have to be referred to their service and connected to that orthopedic surgeon. Doctor-patient confidentiality is guarded in this system. Due to limited experience with this system and unfamiliarity of the patients with such technology, faculty members were also encouraged to connect with patients using any secured mobile or computer applications. As physiotherapy clinics had also been shut down, the patients could learn rehabilitation programs via the VOS. In this method, patients are asked to show their surgical scar area on the video-calls. Whenever a consulting orthopedic surgeon suspects a complication such as surgical site infection or other emergent conditions, the patient is asked to come to the hospital to be treated accordingly. Management of post-operative trauma patients in the time of crisis is more challenging. Many of them have lower compliance in having follow-up sessions via the VOS. There is also a problem in writing follow-up x-rays for the patients. Moreover, there are some patients with non-emergent conditions such as mal- or non-unions, which is not clear how to be managed. Patients who have been managed non-operatively will meet the same problems. First, there is a paucity of contact information from them in the hospitals, and many of them were discharged from the emergency department or clinics, and their data is not registered like for those who have undergone surgical procedures. Second, many of them are terrified to come to our hospital because they are aware that COVID-19 patients fill most of the hospital beds. Consequently, we decided to gather contact information from the emergency department and our clinics. The follow-up calls were made by each orthopedic professor’s senior residents to make sure there will be limited complications due to lack of follow-up.

Management of personal protective equipment (PPE)

To protect our patients and hospital personnel, the hospital board of trustees decided to create a respiratory triage for patients who has the symptoms of COVID-19. After taking history and primary vital signs, patients are either hospitalized or discharged and sent to quarantine according to national protocols that were inspired by WHO guidelines. For those patients with other complaints and trauma patients, the standard routine care is done in the ER in a separate area from those with suspected COVID-19 disease. One should have in mind that even trauma patient without fever or respiratory complaints in the emergency department or any other wards can be silent carriers of the disease. There are some unpublished reports from our colleagues that express trauma patients without a history of fever or respiratory symptoms were found to be COVID-19 patients as well. These patients were mostly detected post-operatively, or by accident once there was a chest X-ray followed by a lung CT scan. Studies have shown that the usual way of confirming the COVID-19, which is RT-PCR, has a sensitivity as low as 60% (12, 13). One research has shown that patients with positive RT-PCR may have a negative CT scan in the first three days (14). These studies rose a big concern among hospital authorities and they decided to act according to WHO guidelines for PPE for COVID-19 (15). Moreover, our department considered and warned all staff, including faculties, residents and operating room nurses to consider all orthopedic patients in the hospital as silent carriers and use precautions at all times and in cases of visiting a diagnosed COVID-19 patient or performing operative or non-operative treatment use PPE as guided by WHO.

Regarding the fact that there are limited supplies for PPE in the whole country and many hospitals in small towns may require many essential types of equipment, we decided to be an excellent example in applying the protocols to preserve PPE as much as possible. One of the ways to minimize the use of PPE, explained by WHO is by using telemedicine to detect COVID-19 patients (15). We used this method to visit our post-op patients and lower the need of actual post-operative visits in the hospital.

We recommended our orthopedic surgeons and residents to cooperate with hospital authorities in the time of need. We believe that the workload on our infectious disease specialists, emergency medicine service, and internal medicine service was unbearable. We were afraid this burnout may cause irreversible damages to both patients and physicians (16). We proudly decided to stand side-by-side to our colleagues in this critical condition. This made the heart of our colleagues in different branches of medicine closer, and by orthopedic residents and faculty members being involved in the treatment of COVID-19 patients, they gained the chance to practice their learnings as a general physician once again along with closeness and teamwork with their other colleagues in the hospital. Chang et al. have reported the same experience in their hospital in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic (4).

Continuing our path to train orthopedic residents and medical students

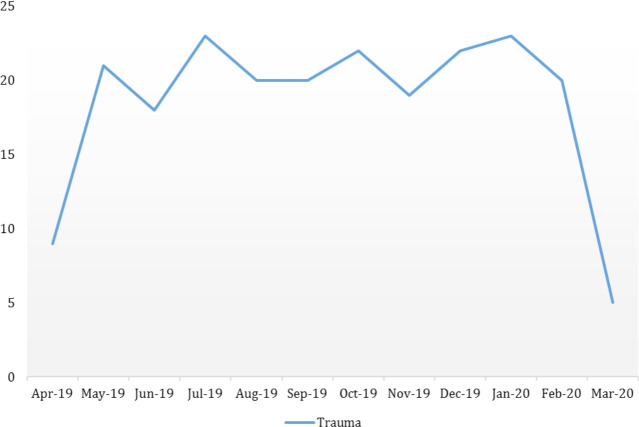

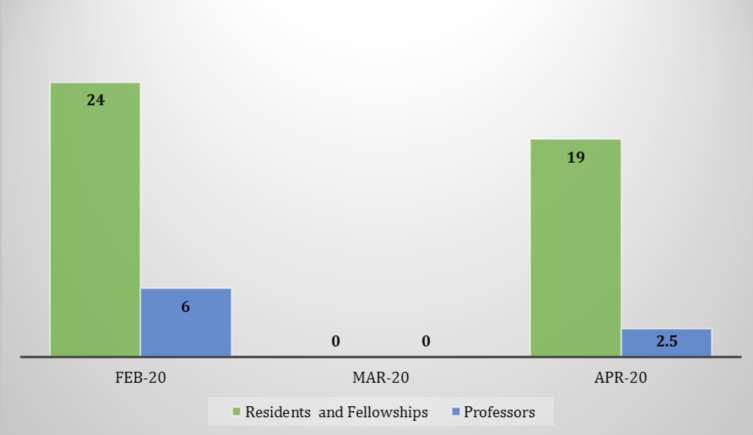

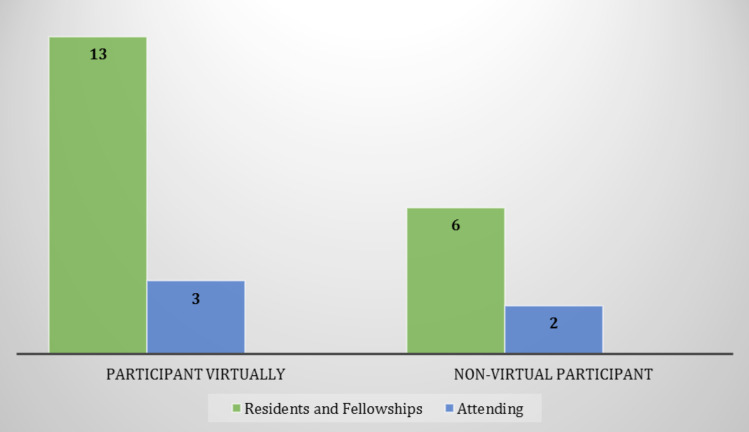

Like many other university hospitals in Iran, educational aspects and training medical students, interns, residents, and nursing students, are inseparable from patients’ treatment. By limiting the hospital routine educational tasks to focus on managing COVID-19 patients, we may put our educational goals at stake. One of the best-known means to reach this educational goal is participation in morning reports which are held five times a week in our center along with two sessions of arthroplasty meetings and one journal club/case presentation session each week. To protect our interns, residents, and attending surgeons, we decided to reduce the number of face to face meetings and mornings and use virtual classes to continue orthopedic education [Figure 4]. As a result, the number of attending residents and orthopedic professors decreased to zero after the initial cancellation of morning report sessions, but eventually, we managed to encourage most of our residents and fellowship orthopedic residents to attend in virtual meetings and morning sessions (Figur 5; 6).

Figure 4.

Number of Morning Report Sessions Before and After the COVID-19 Outbreak

Figure 5.

Mean Number of Participants in The Morning Reports Between February and April 2020

Figure 6.

Comparison Between the Mean Number of Virtual and Non-Virtual Participants in Morning Report Sessions in April 2020

Unfortunately, there is not enough experience in teaching residents using virtual education infrastructures among all medical universities around the country. Due to some limitations such as filtering and sanctions we do not have access to all web-based virtual classroom applications. To overcome this problem, our department decided to use webinars facilitated by Tehran University of Medical Sciences to have interactive sessions to continue our important role in educating next-generation orthopedic surgeons.

Discussion

We believe that the active participation of orthopedic department faculties in the time of the COVID-19 crisis is crucial. Each orthopedic department can establish a protocol according to the hospital infrastructure, facilities, and WHO guidelines to encounter the current situation. We can lower the inevitable damage to both patients and the orthopedic team by limiting the number of elective surgeries and converting the previous treatments and educational systems to more virtually based education and patient visits.

Conflict of interests:

None.

Source of funding:

The authors declare no source of funding

References

- 1.Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O’Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Int J Surg. 2020;76(1):71–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 ( COVID-19): situation report, 51. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dietz L, Horve PF, Coil D, Fretz M, Van Den Wymelenberg K. 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: a review of the current literature and built environment (BE) considerations to reduce transmission. Preprints. 2020;3(1):20200301972020. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00375-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang LZ, Wang W, Murphy D, Po Hui JH. Novel coronavirus and orthopaedic surgery: early experiences from Singapore. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.00236. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, Qin Q. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25748. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41(2):145–51. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KK, Chu H, Yang J, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu YC, Liao CH, Chang CF, Chou CC, Lin YR. A locally transmitted case of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Taiwan. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(11):1070–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Telemedicine: oppor-tunities and developments in member states. Report on the second global survey on eHealth. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi T, Jung SM, Linton NM, Kinoshita R, Hayashi K, Miyama T, et al. Communicating the risk of death from novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):E580. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W, et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020;26(1):200642. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang Y, Zhang H, Xie J, Lin M, Ying L, Pang P, et al. Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200432. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang W, Yan F. Patients with RT-PCR confirmed COVID-19 and normal chest CT. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200702. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19): interim guidance, 27 February 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong AM. Beyond burnout: looking deeply into physician distress. Can J Ophthalmol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2020.01.014. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]