Abstract

The novel coronavirus-induced infection (COVID-19) was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020. Iran is one of the countries with a high incidence of COVID-19 infection.

Data on three patients with fragility hip fracture and COVID-19 infection were collected from one hospital located in Badrud, Isfahan, Iran, from March 1, 2010, to March 30, 2020. All patients were elderly and had fracture induced by fall from standing height.

All patients (n=3) were admitted with fragility hip fracture due to low energy trauma. The most common symptoms were weakness and fatigue. Positive C-reactive protein (CRP) and Leukopenia were the most common abnormal laboratory evaluations. According to the results, two patients underwent surgical treatment, and one patient had negative reverse transcription-CRP; however, all of them underwent medical treatment for COVID-19 infection.

There is a possible relationship between COVID-19 infection and fragility hip fracture in elderly patients. It could be induced by fatigue and weakness due to COVID-19 disease. COVOID-19 infection should be considered in elderly patients with fragility hip fracture during the coronavirus pandemic.

Key Words: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), Fracture, Hip

Introduction

In December 2019, an outbreak of pneumonia of unknown origin developed in Wuhan of Hubei Province, China (1). By January 7, 2020, Chinese scientists confirmed that the outbreak was caused by a novel coronavirus, initially referred to as the 2019-nCoV (2). The disease is now termed as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the WHO.

It is now evident that most cases of COVID-19 develop mild respiratory and constitutional symptoms (3) while some patients might remain asymptomatic (3,4). The reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) has a fair detection rate of 30% to 60% at initial presentation with several other limitations (5). In a recent report from China, chest CT scan had a sensitivity of 97% for diagnosing COVID-19 which is superior to RT-PCR (6). Iran’s ministry of health introduced a RT-PCR as a gold standard for the diagnosis of COVID-19, because it is available and cheaper in Iran which is more positive early in the course of the disease and can be used as a screening tool with higher sensitivity than RT-PCR.

In Iran, the first cases of COVID-19 were officially reported between February 19 and 23, 2020 and it soon became clear that Iran is one of the countries that is worst-hit by COVID-19 outbreak (7, 8).

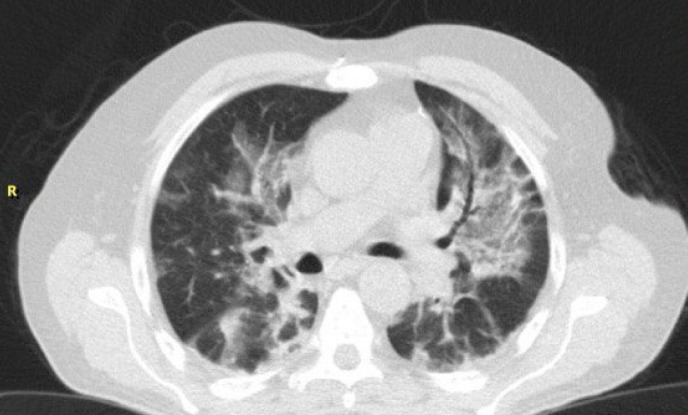

figure 3c.

Chest CT scan with diagnostic pattern before positive RT-CRP

Badrood General Hospital in Badrood city near Kashan and Qom - the epicenters of Iran – is covering 30,000 population where we diagnosed 59 patients with a positive RT-PCR and more than 70 patients were treated based on highly suspected chest CT scan until March 2, 2020,. This number represents a high prevalence of COVID-19 in this city. After reviewing the medical records of our hospital between January 2018 until January 2020, we found only 17 patients admitted with the diagnosis of fragility hip fracture (approximately 0.7 patients a month). Notably only over a month in March 2020, we admitted 3 elderly patients with fragility hip fracture all of whom were diagnosed positive for COVID-19 based on chest CT scan study.

Case presentation

Patient 1

The patient was 73 year old male admitted with intertrochanteric femoral fracture [Figure 1a]. Routine preoperative laboratory exam did not show any abnormality. However, he was complaining of a recent generalized weakness. He underwent surgical fixation under spinal anesthesia and intravenous sedation. His oxygen saturation dropped to 90% during surgery which raised to 96% with face mask and O2 supplement. He was transferred to post anesthesia care unit (PACU) and was discharged from the hospital after 2 days. He returned to the hospital 3 days after discharge with new onset fever, weakness, dyspnea, and anorexia. Initial evaluation ruled out surgical site infection while the chest X-ray was suggestive of COVID-19 leading to readmission of the patient [Figure 1b]. Laboratory results showed positive CRP and elevated liver function tests including AST, ALT, and LDH. Complete blood count (CBC) demonstrated 7.7109 white blood cells/L with 81% neutrophils and 13% lymphocytes illustrating significant lymphocytopenia. Moreoevr, chest HRCT was diagnostic [Figure 1c] although the RT-PCR was negative. Due to the predictive value of the findings, PCR was considered false negative and patient was planned to receive treatment per protocol.

figure 1a.

intertrochanteric hip fracture

figure 1b.

3 days post operative chest X-ray

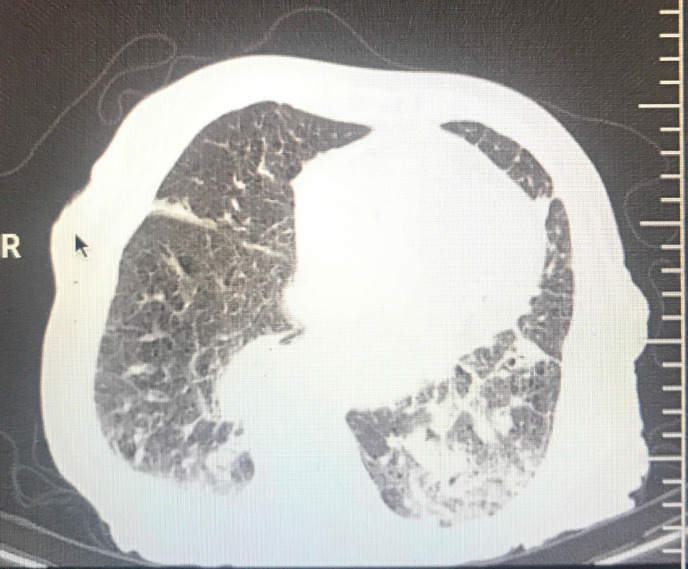

figure 1c.

Chest CT scan which confirmed the diagnosis

Patient 2

The patient was a 69 year old male admitted with intertrochanteric femoral fracture [Figure 2a]. Following our experience with patient 1, we carefully evaluated the patient. He had no fever and no cough but he was complaining of weakness. The chest CT scan was diagnostic [Figure 2b]. In addition, CRP was (2+) and lymphocytopenia (0.6109cells/L) was present while other laboratory studies were in a normal range. The patients were treated in a same manner as was done for patient 1.

figure 2a.

Base of femoral neck fracture due fall from stand height leve

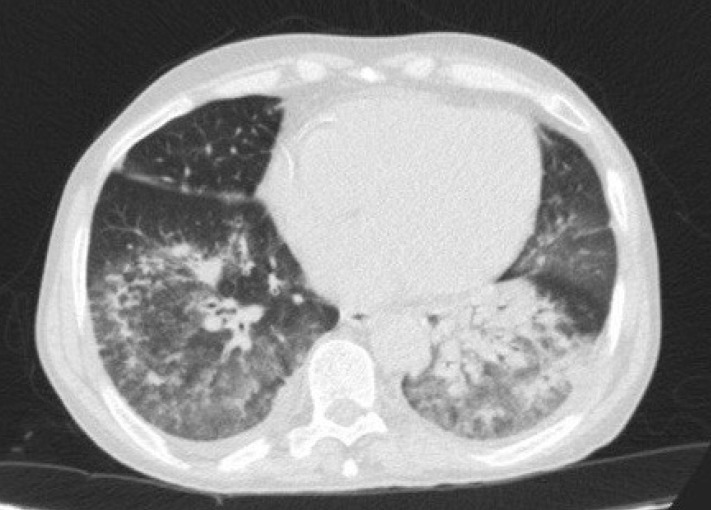

figure 2b.

Initial chest CT scan which was diagnostic for COVID-19 infection

Patient 3

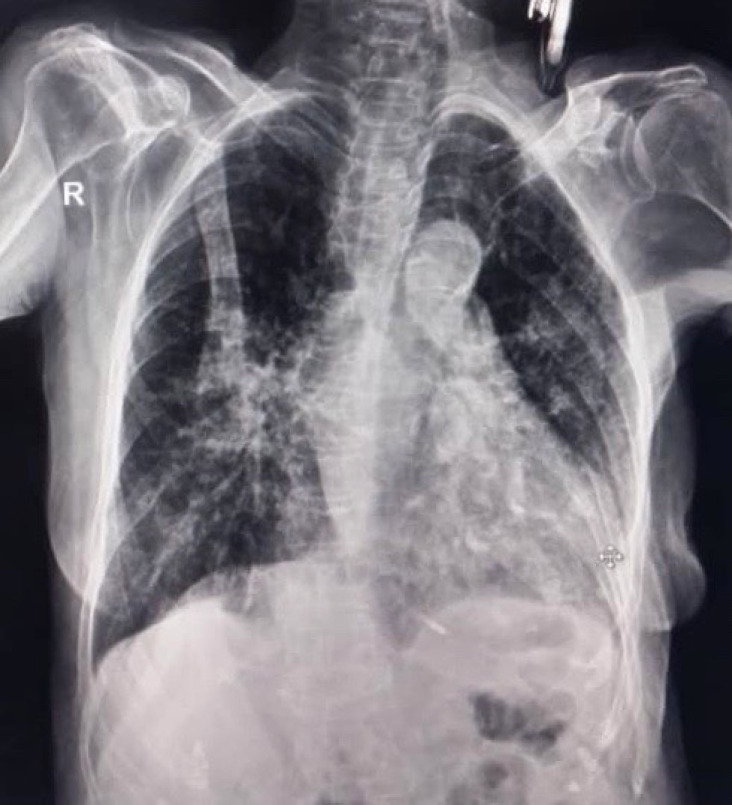

The patient was a 93 year old female admitted with femoral neck fracture [Figure 3a]. Initial examination showed a low grade fever along with cough and feeling of fatigue. Primary laboratory study revealed leukocytosis (1.1109 cells/L) with 8% lymphocyte count (significant lymphopenia). A second CBC after 2 days showed 5.5109 white blood cell/L consisting of 13% lymphocyte. In addition, CRP and LDH were 55 and 472, respectively while other laboratory studies were in a normal range. Initial chest X-ray was highly suggestive [Figure 3b] and the subsequent chest CT scan was diagnostic for COVID-19 [Figure 3c] and RT-PCR was positive. We were urged to postpone surgery due to severe pulmonary involvement.

figure 3a.

left displaced Femoral neck fracture

figure 3b.

Initial Chest x-ray at ED

All three patients received oseltamivir and hydroxychloroquine. One patient also received corticosteroid. At the time of preparing this paper, all three patients are still hospitalized and is in the ICU.

Discussion

To our knowledge, there are only two reports about the possible association between COVID-19 and trauma in the recent literature. The first was reported by Khazaei et al (9). He reported incidental diagnosis of COVID-19 in trauma patients with which he raised the possible association between provisional COVID-19 infection and traumatic events. They did not mention fragility fractures in specific, but they reported falling and car accident as the most frequent mechanisms of injury. Interestingly, most of the patient did not have any symptoms related to COVID-19 at presentation. Second study reported by bobin et al reported 10 patients with COVID-19 infection after sustaining a traumatic fracture in a motor-vehicle accident (10). Of these, 3 patients were negative on RT-PCR exam, but all showed diagnostic features on chest CT scan. They concluded that presentation of symptoms was not different from other COVID-19 patients and was unrelated to having a fracture. They also concluded that lymphopenia was more likely to be found in patients with a fracture.

The observations could be just a coincidence, but there is a possible relationship between COVID-19 infection and fragility fractures as a result of a fall from a standing due to weakness and fatigue arising from the underlying disease. In our case study, the most common chief complaint was weakness and fatigue.

Based on the related algorithm described by British Orthopedic Association for the management of orthopedic patients during coronavirus pandemic, the care of patients with lower limb fragility fractures remain urgent and is a surgical priority which highlights the importance of vigility in this group of patients (11).

Most patients with fragility lower extremity fractures are old and have other underlying conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease, which leads to a lengthy hospital stay as well as requiring PACU, both increasing the chance of transmitting infection to the health care workers and other patients (12). On the other hand, the higher death rate was primarily in elderly people, possibly due to a weaker immune system that permits faster progression of viral infection (13, 14). Additionally, the stress associated with the fracture and the surgery itself can trigger a series of oxidative stress responses and excessive inflammation making them vulnerable to more severe course of infection (15). So, it is advised to carefully evaluate the elderly patients with fragility lower extremity fracture during an outbreak of COVID-19 in order to protect the health and safety of the health care workers.

World Health Organization (WHO) guideline has instructed airway management of confirmed or suspected COVID-19 patients to reduce the risk of viral transmission (16). Nevertheless, to avoid any airway manipulation, the use of regional anesthesia (RA) techniques are preferred when possible (17). The main advantage would be the avoidance of airway instrumentation and patient coughing during intubation and extubation, which reduces the risk of direct contact with generated aerosols and dispersion of viral particles (18).

During a pandemic, it is suggested to consider everyone a COVID-19 positive to take enough precautions when treating a patient. However, elderly patients with fragile lower extremity fractures are those who potentially pose a greater risk to the health care workers. We suggest being vigilant when seeing the patients and use sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE) when interacting. Careful assessment using chest CT scan and other lab tests are recommended during pandemic regardless of having any symptoms to diagnose and separate the COVID-19 patient as soon as possible.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet . 2020;395:497e506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med Adv. 2020;24 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 . Access Published January. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Preven- tion. Jama. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.HuZ , SongC , XuC , JinG , ChenY , XuX , etal Clinical characteristics of 24 asymptomatic infections with COVID-19 screened among close contacts in Nanjing, China. Science China Life Sciences. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1661-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y, Yang M, Shen C, Wang F, Yuan J, Li J, et al. Laboratory diagnosis and monitoring the viral shedding of 2019-nCoV infections. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2020.100061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W, et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020:200642. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MahdaviA , KhaliliN , DavarpanahAH , FaghihiT , Mahdavi A, Haseli S, et al. Radiologic Management of COVID-19: Preliminary Experience of the Iranian Society of Radiology COVID-19 Consultant Group (ISRCC) Iranian Journal of Radiology. (In Press) [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Committee on COVID-19 Epidemiology. Daily Situation Report on Coronavirus disease (COVID19) in Iran; March 13, 2020. Archives of Academic Emergency Medicine. 2020;8(1):e23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khazaei M, Asgari R, Zarei E, Moharramzad Y, Haghighatkhah H, Sanei Taheri M. Incidentally Diagnosed COVID-19 In- fection in Trauma Patients; a Clinical Experience. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8(1):e31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bobin Mi, Lang Chen, Yuan Xiong, Hang Xue, Wu Zhou, Guohui Liu, Characteristics , Early Prognosis of COVID-19 Infection in Fracture Patients, J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;00:1–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.00390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.British Orthopedic Association, BOAST - Management of patients with urgent orthopaedic conditions and trauma during the coronavirus pandemic. vailable from URL: https://www.boa.ac.uk/resources/covid-19-boasts-combined.html.

- 12.HIP ATTACK Investigators. Accelerated surgery versus standard care in hip fracture (HIP ATTACK): an international, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2020 ;395(10225):698–708. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.W Wang J, Tang F. Updated understanding of the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China. 2019;92:441–4. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Q Li X, Guan P. Early transmission dynamics in wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazidi M, Shivappa N, Wirth MD, Hebert JR, Vatanparast H, Kengne AP. The association between dietary inflammatory properties and bone mineral density and risk of fracture in US adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71(11):1273–7. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2017.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) technical guidance: infection prevention and control / WASH. [ (accessed March 2020)]. Available from URL: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-auidance/infection-prevention-and-control (accessed March 2020)

- 17.Peng PW, Ho PL, Hota SS. Outbreak of a new coronavirus: what anaesthetists should know. British journal of anaesthesia. 2020 Feb 27; doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan TK. How severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) affected the Department of Anaesthesia at Singapore General Hospital. Anaesthesia and intensive care. 2004 ;32(3):394–400. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0403200316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]