Abstract

Mice are routinely used to study aqueous humour dynamics. However, physical factors such as temperature and hydration affect outflow facility in enucleated eyes. This retrospective study examined whether differences in temperature and relative humidity experienced by living mice within their housing environment in vivo coincide with differences in outflow facility measured ex vivo. Facility data and environmental records were collected for one enucleated eye from 116 mice (C57BL/6J males, 9–14 weeks) at two institutions. Outflow facility was reduced when relative humidity was below the lower limit of 45% recommended by the UK Code of Practice, but there was no detectable effect of temperature on outflow facility. Even when accounting for effects of humidity, there were differences in outflow facility measured between institutions and between individual researchers at the same institution. These data indicate that humidity, as well as additional environmental factors experienced by living mice within their housing environment, may significantly affect outflow facility measured ex vivo.

Keywords: Outflow facility, housing, temperature, relative humidity, environmental conditions, C75BL/6J mice

A growing community of investigators use mice to study the physiology and pharmacology of aqueous humour outflow and intraocular pressure (IOP). Mouse eyes share anatomical features with primate eyes, such as a continuous Schlemm’s canal and a lamellated trabecular meshwork (Smith et al., 2001; Tamm, 2009; Overby et al., 2014a). Moreover, mice and primates exhibit a similar response to compounds that affect outflow facility (Boussommier-Calleja et al., 2012; Dismuke et al., 2016; Millar et al., 2011; Overby et al., 2014a). The potential for genetic manipulation and the considerable ethical and practical advantages that mice have over primates, make mice an attractive animal model to study aqueous humour outflow dynamics and to develop glaucoma therapies (Dismuke et al., 2016).

Outflow facility may vary with age in mice (Millar et al., 2015; Yelenskiy et al., 2017) and between different inbred strains (Boussommier-Calleja and Overby, 2013; Millar et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018). However, even when controlling for age and strain, outflow facility is still highly variable between individual mice. For instance, baseline values of outflow facility (measured ex vivo) vary by as much as 6-fold between adult male C57BL/6J mice aged between 10 and 14 weeks (Sherwood et al., 2016). Such variability erodes statistical power and increases the number of mice required for experiments. Despite the variability between individuals, outflow facility is tightly correlated between contralateral eyes (Sherwood et al., 2016). This suggests that much of the variability in outflow facility is attributable to true differences between individuals rather than to inaccuracies in the measurement itself. Therefore, it is important to identify the factors contributing to this variability, so as to facilitate experimental designs that minimise variability, improve data quality and reduce animal usage.

Physical factors, such as temperature and hydration during a perfusion, influence outflow facility measured in enucleated mouse eyes (Boussommier-Calleja et al., 2015). In this study, we examined whether temperature and humidity experienced by a living mouse within its housing environment coincide with differences in outflow facility measured after death. In this study, we performed a retrospective analysis of outflow facility measurements over a 1.5-year period, using data generated at two institutions (Imperial College London, ICL, or Trinity College Dublin, TCD) by two co-authors (ERT or JB) working at one or both institutions. We compared outflow facility measured ex vivo against room temperature and humidity over a ~24-hour window preceding each experiment. Environmental conditions were obtained from daily records by veterinary staff made between 08:00 and 12:00. The following information was available at ICL and TCD: the temperature and relative humidity of the holding room at the time of recording and the maximum and minimum temperature and humidity since the previous recording. Additionally, ICL had records of the temperature and relative humidity of the air intake into the individually ventilated cages (IVC) at the time of recording. As IVC temperature and humidity were tightly correlated with room measurements, we based our analysis on room temperature and humidity because these data were available at both institutions.

Inclusion Criteria:

We surveyed all available outflow facility data from measurements carried out at ICL and TCD between July 2016 and December 2017. Inclusion criteria were:

Temperature and relative humidity data were available for the day of the outflow facility measurement.

Outflow facility was measured using iPerfusion following a standard 8-step pressure protocol (Sherwood et al., 2016). All outflow facility measurements were performed in enucleated eyes within 30 minutes of death by cervical dislocation. The perfusion fluid was sterile-filtered Dulbecco’s PBS containing divalent cations and 5.5 mM D-glucose. Eyes were cannulated via the anterior chamber and submerged under PBS at 35°C during the entire perfusion.

Eyes were obtained from wild-type C57BL/6J male mice aged between 9 and 15 weeks at the time of death and housed at a maximum density of 5 mice per cage. Only one eye was included per individual. When data from both eyes were available, we randomly selected which eye was included in the analysis.

Mice did not undergo any surgery or drug treatment prior to death, and eyes were not treated with any additional compounds during the outflow facility measurement.

Applying these inclusion criteria, we gathered outflow facility data from a total of 116 mice, including 60 perfused by ERT at TCD (ERT-TCD), 43 perfused by ERT at ICL (ERT-ICL), and 13 perfused by JB at ICL (JB-ICL). Measurements at TCD were acquired between July 2016 and January 2017, and measurements at ICL were acquired between June and December 2017.

Facility Distributions:

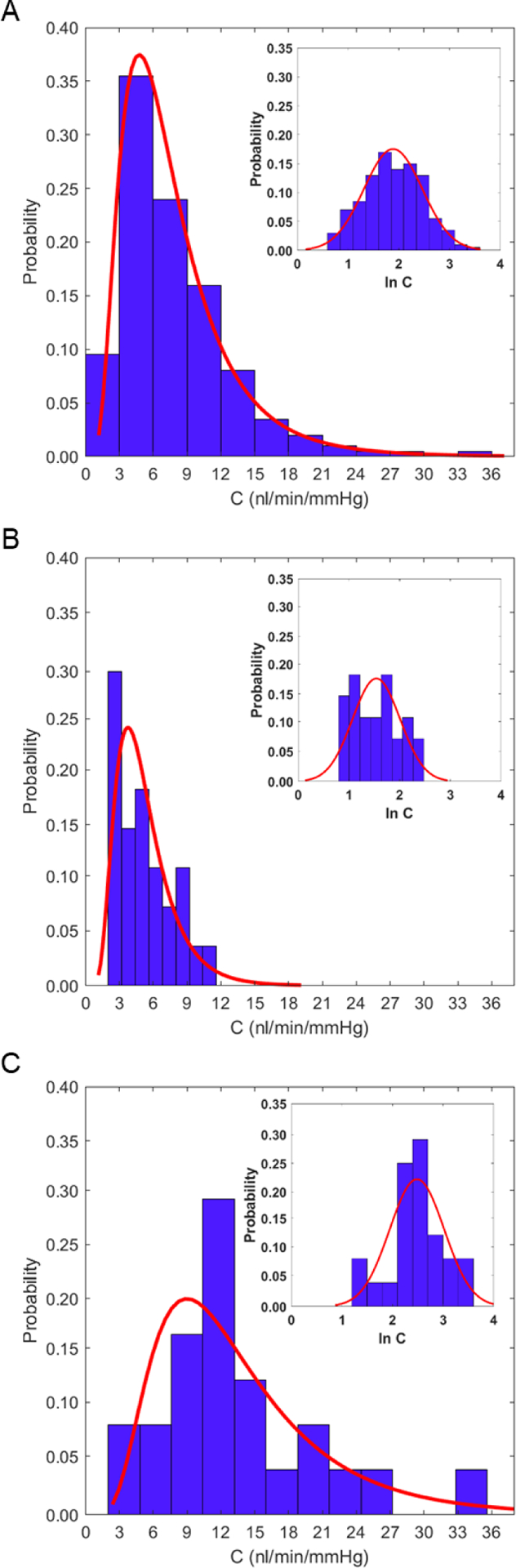

A histogram of data from all 116 mice showed that outflow facility (C) exhibits a skewed, asymmetric distribution consistent with a log-normal distribution, as previously described (Sherwood et al., 2016) (Figure 1A). Likewise, a Shapiro-Wilk test revealed a statistically significant difference from a Gaussian-normal distribution when applied to C (p = 0.0001) that vanished when applied to the natural logarithm of C (p = 0.37; Figure 1A insert). Because most statistical tests assume a Gaussian-normal distribution, we performed all statistical analyses on the natural logarithm of outflow facility (ln C). We then inverted the logarithm (eln C) to report results in terms of outflow facility.

Figure 1:

The log-normal distribution of ex vivo outflow facility (C). A) A histogram of C measured from enucleated eyes from C57BL/6J mice (N = 116) reveals a skewed, asymmetric distribution that is well described by a log-normal distribution. Insert: following log-transformation of C (ln C, where ln represents the natural logarithm), the histogram appears Gaussian-normal, consistent with C being log-normally distributed. Histograms that include only facility data from ERT at ICL (B, N = 27) or ERT at TCD (C, N = 24) when the relative humidity was greater than 45% remain consistent with a log-normal distribution.

The measured values of C ranged from 2.0 to 35.2 nl/min/mmHg with a mean value of 6.6 [6.1, 7.2] nl/min/mmHg (geometric mean [95% confidence interval]; N = 116). These results were consistent with previous iPerfusion measurements by the same researchers (ERT and JB at ICL) on a different cohort of mice having the same strain, sex and age as those in the current study (5.9 [5.3, 6.6] nl/min/mmHg; N = 66, p = 0.78) (Sherwood et al., 2016). There was no detectible relationship between C and age (p = 0.65), although the narrow age range included in this study would have low statistical power to detect such a relationship, even if one did exist.

Effects of Temperature and Relative Humidity:

The UK Home Office Code of Practice recommends that the temperature of a mouse holding room lie between 20°C and 24°C and that the relative humidity lie between 45% and 65% (Great Britain. Home Office, 2014). The same recommendations apply to Ireland. Temperature recordings were largely within these limits, however relative humidity recordings were frequently below the lower limit (Figure 2), particularly during winter months. No facility measurements had a room relative humidity greater than 65% or a room temperature less than 20°C.

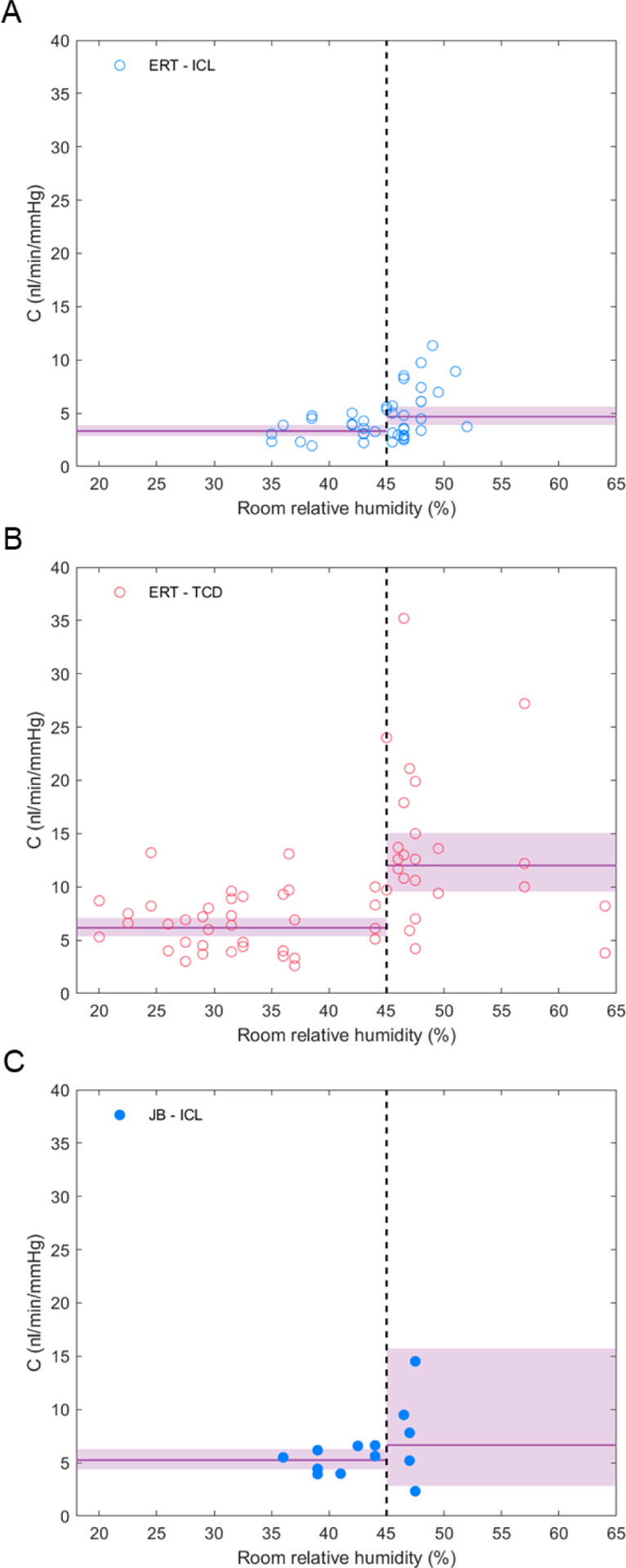

Figure 2:

Outflow facility (C) decreases when room relative humidity decreases below 45%. A) Data from ERT at ICL. B) Data from ERT at TCD. C) Data from JB at ICL. Solid lines represent the geometric mean of C for each group, and the shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals on the mean. The dashed vertical line represents the 45% threshold in relative humidity recommended by the UK Home Office.

We performed an ANOVA to determine whether variability in C was related to variability in room temperature or humidity or to differences between institutions. This analysis set institution as a categorical variable (TCD vs ICL) and temperature and relative humidity as continuous variables, defined as the midpoint between the maximum and minimum recorded room values since the previous daily recording. Data were excluded from one researcher (JB) who did not acquire data at TCD. There was a statistically significant effect of institution on outflow facility (p < 0.001). However, there was no detectible effect of temperature or relative humidity (or interaction between temperature and humidity) as continuous variables on outflow facility (p > 0.2; adjusted R2 = 0.39).

Correlations, such as that performed above, assume that an independent variable (e.g., humidity) has a continuous influence on the dependent variable (e.g., facility) over the full range of the independent variable. This may overlook threshold effects, whereby the dependent variable changes only once the independent variable crosses a particular threshold value. As the recorded relative humidity was frequently below the recommended limit of 45%, we examined whether crossing this lower limit could introduce a threshold change to outflow facility. To test for threshold effects, we performed a second ANOVA defining institution as a categorical variable as above, but also defining temperature and relative humidity as categorical variables (>24°C versus ≤24°C for temperature and <45% versus ≥45% for relative humidity; excluding data from JB). Again, there was a statistically significant effect of institution (p < 0.001), consistent with the continuous analysis above. However, in contrast to the continuous analysis, there was now a statistically significant effect of relative humidity (p < 0.001) on outflow facility. When room relative humidity was ≥ 45%, the mean value of C (measured by ERT at ICL) was 4.7 [3.9, 5.6] nl/min/mmHg (N = 27) compared to 3.3 [2.9, 3.8] nl/min/mmHg (N = 16) when the relative humidity was < 45% (Figure 2A). This corresponded to a 30 [52, 8] % reduction in C when relative humidity was < 45%. A reduction in C was also observed at TCD (Figure 2B), although the facility values measured at TCD were larger than those measured at ICL. The same trend was observed for the data from JB at ICL, although the small sample size did not achieve significance (Figure 2C, Table 1). In contrast, there was no detectible effect of temperature on outflow facility or any detectible interaction between temperature, institution or relative humidity on C (p > 0.1). Thus, a relative humidity below 45% in the mouse holding room coincides with reduced outflow facility measured ex vivo.

Table 1:

Summary of outflow facility (C; mean [95% CI]) measurements per institution, researcher and whether the room relative humidity was inside (≥ 45%) or outside (< 45%) the limits recommended by the UK Home Office.

| Institution | Researcher | Humidity Limits | N | C (nl/min/mmHg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCD | ERT | < 45% | 36 | 6.2 [5.5, 7.1] |

| TCD | ERT | ≥ 45% | 24 | 12.0 [9.6, 14.9] |

| ICL | ERT | < 45% | 16 | 3.3 [2.9, 3.8] |

| ICL | ERT | ≥ 45% | 27 | 4.7 [3.9, 5.6] |

| ICL | JB | < 45% | 8 | 5.2 [4.4, 6.3] |

| ICL | JB | ≥ 45% | 5 | 6.7 [2.8, 15.7] |

The 45% lower limit on relative humidity is an arbitrary threshold. To explore whether this 45% value provides a reasonable threshold to separate the effect of humidity on outflow facility, we calculated the within-class variance whilst varying the separation value between the two facility “classes”. Following Otsu’s method (Otsu, 1979), the separation value that minimises the within-class variance (which simultaneously maximises the between-class variance) represents a logical choice for a threshold. Applying this analysis to log-transformed facility values measured by ERT at ICL and TCD (considered separately) yielded a minimum within-class variance at 47% and 45%, respectively. From this, we conclude that the 45% lower limit for relative humidity recommended by the UK Home Office Code of Practice represents a reasonable threshold for describing the effect of humidity on outflow facility.

Inter-institutional and Inter-individual Differences:

We detected significant inter-institutional and inter-individual differences in the measured values of outflow facility. Between institutions, ERT measured nearly 2-fold larger values of C at TCD relative to ICL (8.0 [7.0, 9.3] vs. 4.1 [3.6, 4.7] nl/min/mmHg, N = 60 vs. 43; p < 0.0001). This difference could not be explained by inter-institutional differences in temperature or relative humidity, because when including only those data within the recommended temperature and humidity limits, the difference not only persisted but increased (11.6 [8.9, 15.1] nl/min/mmHg, N = 19 at TCD vs. 4.4 [3.6, 5.3] nl/min/mmHg, N = 24 at ICL; p < 0.0001). Furthermore, it seems unlikely that the inter-institutional differences could be attributable to a measurement offset between iPerfusion systems because both systems were able to consistently measure (as part of a daily protocol) the hydraulic resistance of a glass capillary of known resistance comparable to that of a mouse eye (Sherwood et al., 2016). Furthermore, both systems measured a similar value of C between contralateral eyes (5 [−25, 21]%, N = 10 pairs, p = 0.64 at TCD versus 8 [−8, 25]%; N = 10 pairs, p = 0.31 at ICL (Sherwood et al., 2016)). Inter-institutional differences in C thus likely reflect the influence of cohort variability (even for the same nominal strain of mice) or environmental factors such as noise level, vibrations or other stimuli or veterinary procedures not considered in this retrospective study (as data were unavailable). It is important to point out that even though mice at both institutions were nominally of the same sub-strain, C57BL/6J mice at ICL were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (the exclusive distributor of JAX™ in Europe) while those at TCD were purchased directly from The Jackson Laboratory and bred in-house. Thus, C57BL/6J mice at both TCD and ICL were derived from founders purchased from Jackson Laboratory stocks. Mice derived from these founders, however, were bred for up to 10 generations separately at Charles River or TCD. Thus, it could be possible that mice at either institution had experienced genetic drift from the founding strain or from one another, contributing to the observed inter-institutional differences in outflow facility.

Between individuals at the same institution, we measured nearly a 30% difference in C (4.1 [3.6, 4.7] for ERT-ICL, N = 43 versus 5.7 [4.4, 7.5] for JB-ICL, N = 13; p = 0.02) despite no apparent difference in strain (all C57BL/6J), temperature or relative humidity (p = 0.31 and p = 0.25 respectively). An ANOVA using data from ICL alone, with user and relative humidity defined as categorical variables, was consistent with these results (p = 0.004 and p = 0.008 for effects of user and humidity, respectively). Inter-individual differences likely reflect differences in personal technique of euthanisation, enucleation and/or cannulation that may significantly affect the measurement of outflow facility. We point out that JB used 33 gauge metallic needles (World Precision Instruments, USA) to cannulate the anterior chamber, whilst ERT used custom-made bevelled glass pipettes with a 100 μm-tip. Future studies should account for inter-institutional and inter-individual differences on outflow facility measurements, even when using such precise techniques as iPerfusion.

We then examined the distribution of outflow facility values above the 45% threshold in relative humidity. We were particularly interested in whether variations in relative humidity outside of the recommended limits and/or difference between institutions could explain the log-normal distribution in C (Figure 1A). When considering only those perfusions within the recommended humidity limits of 45–65%, the outflow facility distribution was still significantly different from Gaussian-normal (p = 0.02, Shapiro-Wilk test, both ERT-TCD and ERT-ICL considered separately, Figure 1B–C) and not statistically different from a log-normal distribution (p = 0.22, p = 0.80, Shapiro-Wilk test, ERT-ICL and ERT-TCD respectively, Figure 1B–C insert) for either institution. This suggests that the log-normal distribution of outflow facility cannot be explained by variations in relative humidity or by differences between institutions or individuals.

Implications:

Mice have a higher thermoneutral temperature than humans, such that at a room temperature of 20°C to 24°C, which is optimized for human comfort, mice experience cold stress. The optimal temperature for mice is between 26 and 29°C (Fischer et al., 2018). Therefore, as the room temperature was mostly below 25°C it may have been the case that the majority of the mice in this study were already cold-stressed, such that we did not detect a threshold effect of temperature on outflow facility. Reduced humidity may also lead to physiological stress associated with dry eye syndrome (Chen et al., 2008) or ringtail (Barthold et al., 2016). Dry eye syndrome is characterised by increased osmolarity of the tear film (Lemp et al., 2011; Sherwin et al., 2015) that could promote fluid transport from the anterior chamber across the cornea (Boussommier-Calleja et al., 2015; Ruberti and Klyce, 2003). With less aqueous passing through the outflow pathway under these conditions, outflow facility may decrease as part of a compensatory mechanism, similar to the decrease in outflow facility observed following aqueous inflow suppression with timolol (Kiland et al., 2004). Decreased humidity, possibly in combination with cold-stress (as the majority of mice in this study were likely cold-stressed), may also lead to dehydration, changes in fluid intake (Nicolaus et al., 2016) and reduced blood pressure, which may affect IOP and ocular physiology (Sherwin et al., 2015). Osmotic perturbation may also affect the anterior chamber angle in mice (Ni et al., 2015), which could affect outflow facility. Alternatively, low values of relative humidity and/or temperature may lead to elevated corticosterone or other stress hormones (Gong et al., 2015) that may contribute to reduced outflow facility (Clark and Wordinger, 2009; Overby et al., 2014b; Overby and Clark, 2015) that persists after death. Future studies could consider measuring stress hormone levels, tear film osmolarity, blood pressure, ocular dimensions or other physiological metrics to determine the physiological mechanism by which reduced humidity or temperature affects outflow facility.

Findings from this study provide a new perspective on prior reports of seasonal variations in IOP observed in both healthy (Cheng et al., 2016; Qureshi et al., 1996) and ocular hypertensive humans (Gardiner et al., 2013; Qureshi et al., 1999). These studies show that IOP tends to be higher during winter months, which has been attributed to reduced sunlight exposure. In our study, there was no seasonal variation in light exposure because the housing environment is on a constant 12-hr dark-light cycle year-round. However, we measured a significantly lower humidity from November to January versus from August to October, and to a lesser extent a reduced room temperature from November to January (Table 2). In line with this, we measured smaller C in November to January compared to in August to October at both institutions (p < 0.0001 for both, Table 2). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that seasonal variations in IOP may be attributable to reduced humidity during the winter, rather than reduced light exposure.

Table 2:

Summary of relative humidity (%), room temperature (°C), and outflow facility (C) measurements per season and institution (ICL includes both ERT-ICL and JB-ICL, (mean [95% CI]).

| Season | Institution | Relative humidity (%) | Temperature (°C) | N | C (nl/min/mmHg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nov – Jan | ICL | 35.6 [34.5, 36.8] | 20.4 [20.2, 20.7] | 8 | 2.9 [2.2, 3.9] |

| Aug – Oct | ICL | 45.8 [44.8, 46.8] | 22.0 [21.9, 22.2] | 36 | 5.2 [4.5, 5.6] |

| Nov – Jan | TCD | 34.7 [33.4, 35.9] | 22.1 [21.7, 22.5] | 25 | 5.6 [4.7, 6.6] |

| Aug – Oct | TCD | 49.0 [48.1, 49.9] | 22.4 [22.0, 22.8] | 23 | 10.9 [8.4, 14.1] |

This study reveals that the relative humidity experienced by living mice in their housing environment significantly influences outflow facility measured ex vivo. Reductions in relative humidity below 45% recommended by the UK Home Office coincide with reduced outflow facility, likely associated with physiological stress. There are significant differences in the measured values of outflow facility between institutions and between individual researchers at the same institution, beyond that attributable to differences in humidity. This study emphasizes the importance of controlling environmental factors within the housing environment as well as personal technique on the measurement of outflow facility in mice.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out with the financial support of the US National Institutes of Health EY022359 (D.R.O.) and the European Research Council ERC-2012-AdG 322656-Oculus (P.H.). The authors want to thank Dr. Michael Madekurozwa and Mr. Edgar Ibarguen (Imperial College London) for their technical assistance and Prof. C. Ross Ethier (Georgia Institute of Technology) for his critical input on the manuscript.

Support: NIH grant EY022359 and ERC-2012-AdG 322656-Oculus

Footnotes

For temperature and relative humidity, linear regression of IVC versus room measurements yielded R2 = 0.84 and R2 = 0.77, respectively (p < 0.0001; N = 307 daily measurements at ICL).

The average humidity at ICL was 44.6 [43.1, 45.8] % with a range of 17%, while at the average humidity at TCD was 38.8 [36.0, 41.6] % with a range of 44% (p = 0.001). The average temperature at ICL was 22.1 [21.8, 22.4] °C with a range of 3.5°C, while the average temperature at TCD was 23.1 [22.7, 23.4] °C with a range of 6.3°C (p < 0.0001).

References

- Barthold SW, Griffey SM, Percy DH, 2016. Pathology of laboratory rodents and rabbits, 4 ed Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Boussommier-Calleja A, Bertrand J, Woodward DF, Ethier CR, Stamer WD, Overby DR, 2012. Pharmacologic manipulation of conventional outflow facility in ex vivo mouse eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53, 5838–5845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussommier-Calleja A, Li G, Wilson A, Ziskind T, Scinteie OE, Ashpole NE, Sherwood JM, Farsiu S, Challa P, Gonzalez P, Downs JC, Ethier CR, Stamer WD, Overby DR, 2015. Physical factors affecting outflow facility measurements in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56, 8331–8339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussommier-Calleja A, Overby DR, 2013. The influence of genetic background on conventional outflow facility in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54, 8251–8258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Zhang X, Zhang J, Chen J, Wang S, Wang Q, Qu J, 2008. A murine model of dry eye induced by an intelligently controlled environmental system. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49, 1386–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, Xiao M, Xu H, Fang S, Chen X, Kong X, Sun X, 2016. Seasonal changes of 24-hour intraocular pressure rhythm in healthy Shanghai population. Medicine (Baltimore) 95, e4453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AF, Wordinger RJ, 2009. The role of steroids in outflow resistance. Exp Eye Res 88, 752–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dismuke WM, Overby DR, Civan MM, Stamer WD, 2016. The value of mouse models for glaucoma drug discovery. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 32, 486–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AW, Cannon B, Nedergaard J, 2018. Optimal housing temperatures for mice to mimic the thermal environment of humans: An experimental study. Mol Metab 7, 161–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner SK, Demirel S, Gordon MO, Kass MA, Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study, G., 2013. Seasonal changes in visual field sensitivity and intraocular pressure in the ocular hypertension treatment study. Ophthalmology 120, 724–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S, Miao YL, Jiao GZ, Sun MJ, Li H, Lin J, Luo MJ, Tan JH, 2015. Dynamics and correlation of serum cortisol and corticosterone under different physiological or stressful conditions in mice. PLoS One 10, e0117503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Great Britain. Home Office, 2014. Code of practice for the housing and care of animals bred, supplied or used for scientific purposes. Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London. [Google Scholar]

- Kiland JA, Gabelt BT, Kaufman PL, 2004. Studies on the mechanism of action of timolol and on the effects of suppression and redirection of aqueous flow on outflow facility. Exp Eye Res 78, 639–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemp MA, Bron AJ, Baudouin C, Benitez Del Castillo JM, Geffen D, Tauber J, Foulks GN, Pepose JS, Sullivan BD, 2011. Tear osmolarity in the diagnosis and management of dry eye disease. Am J Ophthalmol 151, 792–798 e791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar JC, Clark AF, Pang IH, 2011. Assessment of aqueous humor dynamics in the mouse by a novel method of constant-flow infusion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52, 685–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar JC, Phan TN, Pang IH, Clark AF, 2015. Strain and age effects on aqueous humor dynamics in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56, 5764–5776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y, Xu B, Wu L, Du C, Jiang B, Ding Z, Li P, 2015. Assessment of full-eye response to osmotic stress in mouse model In Vivo using Optical Coherence Tomography. J Ophthalmol 2015, 568509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaus ML, Bergdall VK, Davis IC, Hickman-Davis JM, 2016. Effect of ventilated caging on water intake and loss in 4 strains of laboratory mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 55, 525–533. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsu N, 1979. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 9, 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Overby DR, Bertrand J, Schicht M, Paulsen F, Stamer WD, Lütjen-Drecoll E, 2014a. The structure of the trabecular meshwork, its connections to the ciliary muscle, and the effect of pilocarpine on outflow facility in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55, 3727–3736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overby DR, Bertrand J, Tektas OY, Boussommier-Calleja A, Schicht M, Ethier CR, Woodward DF, Stamer WD, Lütjen-Drecoll E, 2014b. Ultrastructural changes associated with dexamethasone-induced ocular hypertension in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55, 4922–4933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overby DR, Clark AF, 2015. Animal models of glucocorticoid-induced glaucoma. Exp Eye Res 141, 15–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi IA, Xi XR, Lu HJ, Wu XD, Huang YB, Shiarkar E, 1996. Effect of seasons upon intraocular pressure in healthy population of China. Korean J Ophthalmol 10, 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi IA, Xiao RX, Yang BH, Zhang J, Xiang DW, Hui JL, 1999. Seasonal and diurnal variations of ocular pressure in ocular hypertensive subjects in Pakistan. Singapore Med J 40, 345–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruberti JW, Klyce SD, 2003. NaCl osmotic perturbation can modulate hydration control in rabbit cornea. Exp Eye Res 76, 349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin JC, Kokavec J, Thornton SN, 2015. Hydration, fluid regulation and the eye: in health and disease. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 43, 749–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood JM, Reina-Torres E, Bertrand JA, Rowe B, Overby DR, 2016. Measurement of outflow facility using iPerfusion. PLoS One 11, e0150694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li G, Read AT, Navarro I, Mitra AK, Stamer WD, Sulchek T, Ethier CR, 2018. The relationship between outflow resistance and trabecular meshwork stiffness in mice. Sci Rep 8, 5848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelenskiy A, Ko MK, Chu ER, Gonzalez JM, Siegmund K, Tan JC, 2017. Total outflow facility in live C57BL/6 mice of different age. Biomed Hub 2, 6–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]