Abstract

Fossil fuel sources are a limited resource and could eventually be depleted. Biofuels have emerged as a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Jatropha has grown in significance as a potential bioenergy crop due to its high content of seed oil. However, Jatropha’s lack of high-yielding seed genotypes limits its potential use for biofuel production. The main cause of lower seed yield is the low female to male flower ratio (1:25–10), which affects the total amount of seeds produced per plant. Here, we review the genetic factors responsible for floral transitions, floral organ development, and regulated gene products in Jatropha. We also summarize potential gene targets to increase seed production and discuss challenges ahead.

Keywords: Jatropha curcas, energy crop, transcriptome, biofuel, ABCDE model

Introduction

About 11 billion tons of oil is consumed worldwide each year for fuel. With this rate of oil consumption, we may soon exhaust the oil reservoir (Shafiee and Topal, 2009)2. Climate change is also greatly influenced by fossil fuel combustion. Therefore, sustainable and environmentally friendly alternative energy sources are needed. Jatropha curcas L (Euphorbiaceae) is a plant with potential for biodiesel production due to its high seed oil content (around 45–50%) (Achten et al., 2008). Compared with other oil plants, Jatropha has its own merits, including an outstanding adaptability to varied environments, smooth propagation, and greater fruit and seed size. Furthermore, Jatropha grows well in the desert, adapts to drought conditions, has a short gestation period, and assists in soil conservation. Despite its advantageous properties for biodiesel production, Jatropha has some limitations that restrict its commercialization as an energy crop, such as low seed yield, inconsistent flowering and fruiting, and relatively expensive plantation maintenance. The significant factors influencing its potential as biofuel feedstock are the oil content in seeds, the number of seeds per tree, the number of fruits on each branch of the plant, and the number of branches per plant. Seed yield at each inflorescence is largely dependent on the number of female flowers. Jatropha’s female to male flower ratio is quite small (1:25 to 1:30), which means that each inflorescence contains only about 10 to 12 female flowers (out of 300) that yield just 8 to 10 fruits. Therefore, a relatively small number of fruits are produced as compared to the total number of flowers (Kumar and Sharma, 2008). One way to increase the total seed yield in Jatropha would be to increase the number of female flowers per plant. In this context, we have discussed the genetic factors involved in the floral transformation, determination of sex, and floral growth of Jatropha curcas.

Biology of Sex Determination in Jatropha Curcas

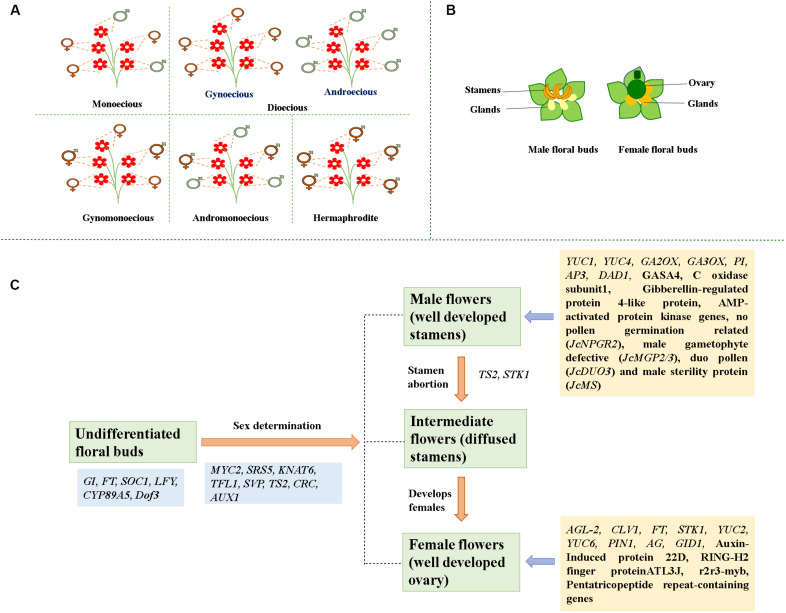

Sex determination processes allow floral organ development in plants. The two processes for forming a unisexual flower are (i) emergence of only one type of sex organ (unisexual tissues) and (ii) initiation of stamen and pistil followed by an arrest or abortion of one sex organ, which results in the functional immaturity of either stamens or carpels. The developmental arrest step occurs at an immature stage well before sexual maturity is reached (Ainsworth, 1999, 2000; Kater et al., 2001). There are two modes of sex determination and development in Jatropha. One mode is the development of male flowers with early adolescence without any female primordia. The other mode is by aborting male tissues, which results in female flowers developing (Li and Li, 2009; Wu et al., 2011). The male flower is unisexual right from the start, whereas the female flower is bisexual until its sixth developmental phase. Because of this, an inflorescence has three types of flowering sites; (i) female flowering site, (ii) male flowering site, and (iii) middle flowering site where both males and females may develop. Though male tissue abortion occurs in female flowers during sexual differentiation, traces of male tissue may be found in mature females. However, when abortion of male tissues fails in a female flower, it develops as a male at the female flowering site. Such inflorescence is known as middle type inflorescence. Due to the number of female flowers formed at middle type inflorescence, variation in the total number of female flowers occurs. An inflorescence statistical analysis found ∼75 percent of middle-type inflorescence and 0.09 percent of female flowers (Luo et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2011). For 18 female locations, Wu et al. (2011) found only seven female flowers. The female flowering sites and the sites occupied by middle-type inflorescence are important in increasing the number of female flowers. The presence of hermaphroditic flowers has also been recorded in Jatropha, showing structural similarity with female flowers but diffused stamens (Abdelgadir et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2011; Adriano-Anaya et al., 2016). A recent population analysis on Jatropha’s floral diversity and sex expression has grouped accessions into gynoecious (having only females), androecious (having only males flowers), and andromonoecious (having both bisexual and male flowers) plants showing no correlation with their geographic location (Adriano-Anaya et al., 2016). Of the 103 accessions from 33 sites in southern Mexico, 93.2 percent were monoecious, while others were androgynomonoecious, androecious, or gynoecious (Figures 1A,B). It has been hypothesized that male development commences through suppression of females, which might be the result of male sterility mutation in gynomonoecious plants (Salvador-Figueroa et al., 2015; Adriano-Anaya et al., 2016). No gynomonoecious plants of Jatropha have been found. The possible explanation, according to Adriano-Anaya et al. (2016), is that gynoecious Jatropha plants derive from hermaphrodite ancestors through a one-step mutation.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Diversified morphology of flowers.  Represents male flowers;

Represents male flowers;  Represents female flowers;

Represents female flowers;  Represents hermaphrodite flowers. (B) Morphology of male and female floral buds in Jatropha.

(C) Key genes involved in the floral transition, sex determination, and reproductive organ development (GI-GIGANTEA; FT-FLOWERING LOCUS T; SOC1-SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS 1; LFY-LEAFY; CYP89A5-CYTOCHROME P450; SRS5-SHI-RELATED SEQUENCE 5; KNAT6-KNOTTED1-LIKE HOMEOBOX GENE 6; TFL1-TERMINAL FLOWER 1; SVP-SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE; TS2-TASSELSEED2; CRC-CRABS CLAW; AUX1-Auxin transporter protein 1; STK1-SEEDSTICK; YUC1-Flavin-containing monooxygenase; YUC2/4/6-Indole-3-pyruvate monooxygenase; GA3ox-Gibberellin 3-beta-hydroxylase; GA20ox-Gibberellin 20-oxidase; PI-PISTILLATA; AP3-APETALA3; DAD1-DEFECTIVE IN ANTHER DEHISCENCE 1; GASA4-Gibberellin-regulated protein 4 precursor; AGL2-AGAMOUS-LIKE 2; CLV1-CALVATA1; PIN1-PIN-FORMED 1; AG2-AGAMOUS-like protein 2; GID1-Gibberellin receptor protein).

Represents hermaphrodite flowers. (B) Morphology of male and female floral buds in Jatropha.

(C) Key genes involved in the floral transition, sex determination, and reproductive organ development (GI-GIGANTEA; FT-FLOWERING LOCUS T; SOC1-SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS 1; LFY-LEAFY; CYP89A5-CYTOCHROME P450; SRS5-SHI-RELATED SEQUENCE 5; KNAT6-KNOTTED1-LIKE HOMEOBOX GENE 6; TFL1-TERMINAL FLOWER 1; SVP-SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE; TS2-TASSELSEED2; CRC-CRABS CLAW; AUX1-Auxin transporter protein 1; STK1-SEEDSTICK; YUC1-Flavin-containing monooxygenase; YUC2/4/6-Indole-3-pyruvate monooxygenase; GA3ox-Gibberellin 3-beta-hydroxylase; GA20ox-Gibberellin 20-oxidase; PI-PISTILLATA; AP3-APETALA3; DAD1-DEFECTIVE IN ANTHER DEHISCENCE 1; GASA4-Gibberellin-regulated protein 4 precursor; AGL2-AGAMOUS-LIKE 2; CLV1-CALVATA1; PIN1-PIN-FORMED 1; AG2-AGAMOUS-like protein 2; GID1-Gibberellin receptor protein).

Genetic Factors for Vegetative to a Reproductive Phase Transition

In floral initiation, the apical shoot meristem differentiates into an inflorescence. The induction of floral signaling is genetically controlled by floral integrator genes, such as FT (FLOWERING LOCUS T), FLC (FLOWERING LOCUS C) and SOC1 (SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS 1). Ye et al. (2014) reported that JcFT (Jatropha Flowering locus T) overexpression caused early flowering by shortening the bolting time. Li et al. (2014) characterized FT in Jatropha, and data from its spatial expression showed higher expression in reproductive phases. The LFY gene has recently been identified and overexpressed in both Arabidopsis thaliana and Jatropha (Tang et al., 2016). During the early stages of flowering, they observed a higher expression of JcLFY (Jatropha LEAFY). Transgenics with JcLFY overexpression showed early flowering and increased transcript levels of floral meristem identity genes, such as JcAP1, JcAP3, JcSEP1, JcSEP3, and JcAG. In addition, co-suppression of LFY in Jatropha resulted in delayed flowering, abnormal floral flowers replaced by sepaloid organs, and an increased rate of floral abortion (Tang et al., 2016). Recently, the role of TFL1 homologs has been studied through the transgenic method, and their overexpression has resulted in delayed flowering due to reduced AP1 and FT gene expression (Karlgren et al., 2013; Li et al., 2017). In contrast, Li et al. (2014) reported higher expression of FT in Jatropha’s reproductive phases and fruits. Circadian rhythms play an important role in the initiation of flowering. JcDof3, a plant-specific transcription factor with a conserved zinc finger (ZF) DNA-binding domain, is a circadian clock regulated gene. The C-terminal conserved region of Dof3 interacts with the F-box protein forming Dof3-Fbox complex regulating the expression of CO, a circadian clock regulating flowering gene (Yang et al., 2011). Foliar cytokinin (CTK) treatment upregulates genes GI, SOC1, and LFY, and inactivates genes COP1 and TFL1b that maintain a flowering signal which promotes flowering (Chen et al., 2014; Pan et al., 2014). Thus, the interplay between the circadian rhythm and hormones control flowering genes and phase transition to inflorescence meristem in Jatropha.

Molecular Basis of Sex Determination

Jatropha is a monoecious plant in which female flowers are formed due to stamen abortion/suppression. Remains of female tissues are not observed in male flowers, though remains of aborted stamens (male tissues) are present at the base in female flowers. By analyzing Jatropha floral buds for gene expression, the SUPERMAN gene was observed to suppress male tissue and promote the development of female tissue (Gangwar et al., 2018). A recent study suggested that, in Arabidopsis, the SUPERMAN gene not only bridges floral organogenesis and floral meristem but also regulates auxin biosynthesis (Xu et al., 2018). Transcriptome analysis of Jatropha’s floral buds showed reduced expression of the stamen development gene TASSELSEED 2 (TS2) that facilitated the growth of carpels (Chen et al., 2014). Transcriptomic analysis of different stages of male and female flower buds of Jatropha showed upregulation of CRABS CLAW (CRC) during development stages of female flowers. CRC, a C2C2-YABBY zinc finger protein, is involved in the regulation of carpel fusion and growth, nectary formation, and floral meristem termination (Xu et al., 2016; Gross et al., 2018). Genes encoding for inorganic phosphate transporter and ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase were upregulated during female flower development and may contribute to embryo sac development (Xu et al., 2016). Further, upregulation of genes encoding for chlorophyll A/B-binding protein during initiation of carpel primordia may facilitate carpel differentiation. Genes encoding for Gibberellin-regulated protein 4-like protein, cytochrome c-oxidase subunit 1 (mitochondrial gene), and AMP-activated protein kinase, however, were upregulated during stamen development. Upregulation of genes encoding for RING-H2 finger protein ATL3J (E3 ubiquitin ligases), CLAVATA1 (receptor-like kinase), auxin-induced protein 22D, transcription factor R2R3-myb (regulating cell cycle genes and cytokinin signaling), and AGAMOUS-LIKE-20 (MADS-box genes) have been identified during the late stage of female flower development, which may facilitate the maturation of female flower (Alvarez and Smyth, 1999; Pelaz et al., 2000; Makkena et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2016). In both male and female flower buds, genes such as ARP1 (Auxin repressed protein), X10A (auxin-induced protein), and GID1 (gibberellin receptor protein) were upregulated (Xu et al., 2016). The role of JcFT, a florigen and a key flowering pathway regulator in Jatropha showed significantly high transcript levels in female flowers (Li et al., 2014). Another transcriptomic study identified MYC2, TS2, KNAT6, SVP, TFL1, and SRS5 as sex determination regulators in J. curcas (Chen et al., 2017). The suppression of nodulin MtN3 or LESS ADHERENT POLLEN (LAP3) resulted in small anthers, sterile pollens, and abortion of female flowers in Oryza sativa, Vitis vinifera, and Medicago truncatula (Chu et al., 2006; Ramos et al., 2014). In Pisum sativum L, carpel senescence has been induced as a result of increased lipoxygenase gene expression (Rodríguez-Concepción and Beltrán, 1995). Pentatricopeptide repeat-containing gene is expressed in the female embryo sac and restores the cytoplasmic male sterility in Jatropha (Bentolila et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2016). Key genes involved in the floral transition, sex determination and development of reproductive organs are shown in Figure 1C and Table 1. These studies shed light on how sex determination and differentiation occur in monoecious plants and how some of the genes expressed during floral differentiation suppress male flowering.

TABLE 1.

Key genes involved in the floral transition, sex determination, and reproductive organ development.

|

Vegetative to reproductive stage | |||

| Gene name | Plant spp. | Pathway/Association | References |

| 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase (ACS1) | Cucumis sativus | Ethylene biosynthesis | Switzenberg et al., 2014 |

| 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase 7 (ACS7) | Cucumis sativus | Ethylene biosynthesis | Switzenberg et al., 2014 |

| Agamous (AG) | Populus trichocarpa | MADS-box regulators of differentiation, Homeotic genes | Brunner et al., 2000 |

| Apetala 1/3 (AP1/3) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Floral meristem identity genes | Karlgren et al., 2013 |

| Dof3 | Arabidopsis thaliana | F-box protein regulates flowering time | Imaizumi, 2010 |

| Flowering locus C (FLC) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Florigen signaling | Li et al., 2014 |

| Flowering Locus T (FT) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Florigen signaling | Li et al., 2014 |

| GIGANTEA (GI) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Circadian clock control and photoperiodism | Mizoguchi et al., 2005 |

| LFY | Arabidopsis thaliana | Florigen signaling | Tang et al., 2016 |

| Sepallata (SEP1/3) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Floral meristem identity genes | Pelaz et al., 2000 |

| Suppressor of constans overexpression 1 (SOC1) | Arabidopsis thaliana | MADS-box protein | Chen et al., 2014 |

|

Genes associated with flowering sex determination | |||

| Aborted microspores (AMS) | Arabidopsis thaliana; Capsicum annuum L. | Pollen and anther development | Ye et al., 2010; Guo et al., 2018 |

| Agamous (AG2) | Elaeis guineensis | Ovule primordia and carpel | Favaro et al., 2003; Adam et al., 2007 |

| Agamous-like-2 (AGL-2) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Induces microsporogenesis, Embryo sac development | Pelaz et al., 2000 |

| Apetala 3 (AP3) | Elaeis guineensis | Development of male tissues | Favaro et al., 2003; Adam et al., 2007 |

| ARF 10/16/17/18 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Female organ abortion | Huang et al., 2016 |

| ATL3J | Zea mays | Embryo sac development | Xu et al., 2016 |

| Auxin induced protein (X10A) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Stamen differentiation and embryo sac development | Xu et al., 2016 |

| Auxin repressed protein (ARP1) | Nicotiana tabacum | Pollen maturation | Nakamura et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2016 |

| Clavata1 (CLV1) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Peptide-receptor signaling | Alvarez and Smyth, 1999 |

| CRABS CLAW (CRC) | Arabidopsis thaliana; Oryza sativa | Carpel fusion and growth, forming nectary | Gross et al., 2018 |

| Cup-shaped cotyledon 2 (CUC2) | Arabidopsis thaliana; Silene latifolia | Forms boundary between the organs and separates organs with meristem | Li et al., 2010 |

| Defective in Tapetal development and function 1 (TDF1) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Pollen and anther development | Zhu et al., 2008 |

| Duo pollen (DUO3) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Regulator of Male Germline and embryogenesis | Brownfield et al., 2009 |

| Floral binding protein 11 (FBP11) | Cucumis sativus | Ovule formation | Favaro et al., 2003 |

| Gibberellin receptor protein (GID1) | Oryza sativa | Stamen differentiation and embryo sac development | Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2016 |

| Less adherent pollen (LAP3) | Oryza sativa, Vitis vinifera, Medicago truncatula | Pollen development | Chu et al., 2006; Ramos et al., 2014 |

| Lonely guy (LOG) | Oryza sativa | Maintains floral meristem activity and ovule development | Yamaki et al., 2011 |

| Male gametophyte defective (MGP2/3) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Pollen tube growth and pollen germination | Deng et al., 2010 |

| No pollen germination related (NPGR2) | Arabidopsis thaliana | A calmodulin-binding protein regulated pollen germination | Golovkin and Reddy, 2003 |

| Pistillata (PI) | Elaeis guineensis | Development of male tissues | Favaro et al., 2003; Adam et al., 2007 |

| Seedstick1 (STKI) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Carpel development | Pinyopich et al., 2003 |

| Sporocyteless/nozzle (SPL/NZZ) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Regulates anther cell differentiation | Liu et al., 2009 |

| Superman (SUP) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Suppresses stamen development | Prunet et al., 2017 |

| Tasselseed 2 (TS2) | Zea mays | Stamen development by Pistil abortion | Acosta et al., 2009 |

| YUCCA (YUC1/2/4/6) | Arabidopsis thaliana | Stamen development | Stepanova et al., 2011 |

|

ABCDE Model Genes | |||

| Pistillata (PI) | Elaeis guineensis; Jatropha curcas | B-class, stamen development | Favaro et al., 2003; Adam et al., 2007; Hui et al., 2017 |

|

ABCDE Model Genes | |||

| Gene name | Plant spp. | Pathway/Association | References |

| Apetala 3 (AP3) | Elaeis guineensis; Jatropha curcas | B-class, stamen development | Favaro et al., 2003; Adam et al., 2007; Hui et al., 2017 |

| Agamous (AG) | Jatropha curcas; Populus trichocarpa | C-class, carpel differentiation | Brunner et al., 2000; Hui et al., 2017 |

| SEEDSTICK1 (STKI) | Arabidopsis thaliana; Jatropha curcas | D-class, carpel maturation | Pinyopich et al., 2003; Hui et al., 2017 |

| Sepallata (SEP) | Arabidopsis thaliana; Jatropha curcas | E-class, male floral initiation | Pelaz et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2019 |

Abcde Model for Sex Differentiation

The ABCDE model is a scientific model that specifies the role of homeotic genes in the development of floral organs. Genes of the A class specify sepal development. The development of petals occurs by the combined effect of genes from the A and B classes. Both the B- and C-class genes are important for stamen growth. The carpel development and activity of ovules are determined by C-class and D-class genes, respectively. Recently, E-class genes were discovered to play a role in the development of carpel and ovary (Pelaz et al., 2000; Honma and Goto, 2001). A-, B-, C-, D-, and E-class genes are transcription factors with conserved DNA binding domains known as the MADS-box family and are involved in floral organogenesis regulation (Parěnicová et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2019). PERIANTHA (PAN), a bZIP transcription factor, activates AG, a C-class MADS-box protein that regulates floral organ numbers and whorl patterning (Maier et al., 2009). In Elaeis guineensis, the mutants AP3 and PISTILLATA (PI) inhibited male tissues. AG2 has a mixed C/D function gene, and its expression has been observed in ovule primordia and carpel of Arabidopsis and Elaeis guineensis, respectively (Favaro et al., 2003; Adam et al., 2007). FLORAL BINDING PROTEIN 11 (FBP11), a D-class gene, determines the formation of ovules in cucumbers (Favaro et al., 2003). An increase in the C-class gene transcription level arrests the development of sexual organs in monoecious plants, such as Liquidambar styraciflua L and Rumex acetosa L (Ainsworth, 2000). B-and C-class genes are regulated at a sex locus by a genetic switch that further controls the development of male or female flowers in Populus trichocarpa (Leseberg et al., 2006). B-class genes PI and AP3 have been identified in the formation of stamen in Jatropha. A- and C-class gene AG and D-class gene SEEDSTICK1 (STKI) have been reported for carpel development and maturation (Hui et al., 2017). Thus, the ABCDE model helps to understand the floral differentiation in Jatropha.

Role of Hormones in Sex Determination

The process of flower development and sex determination is regulated by the interplay of endogenous hormones (auxins, cytokinins, gibberellins, abscisic acids, etc.). Auxin regulates sex determination in Jatropha. IAA enhanced female to male ratio from 1:27 to 1:23, and it also increased seed weight 3-fold (Joshi et al., 2011). Auxin biosynthesis and signaling are associated with genes such as ARFs, AUX1, and Transport inhibitor response 1 (TIR1). Transcriptome analysis of Jatropha suggested that AUX1 is responsible for sex determination. The main source of auxin production is through Trp-dependent auxin biosynthesis, which participates in embryo patterning and reproductive organ development (Chen et al., 2017). In this pathway, IAA is produced from indole-3-pyruvic acid by YUCCA (YUC), a flavin-dependent monooxygenase (Stepanova et al., 2008). During stamen primordia formation, auxin is produced locally by YUC1 and YUC4 followed by YUC2 and YUC6 genes at late stages of stamen development (Cheng et al., 2006; Cecchetti et al., 2008). In mature gynoecia, YUC4 and YUC8 genes were expressed in the style, whereas YUC2 was expressed in carpel valve tissues (Martínez-Fernández et al., 2014). Increased expression of ARF 10/16/17/18 leads to abnormalities in females and abortion of organs, resulting in fewer seed sets (Huang et al., 2016).

Gibberellic acids also contribute to the development of the stamens in monoecious plants. Exogenous application of GA on the inflorescences of Jatropha resulted in a 2-fold increase in female flowering. However, inflorescence branches were not affected. Hui et al. (2018) reported the altered endogenous CTK (increased) and GA (decreased) ratio due to exogenous GA application, which resulted in an increased proportion of female flowers. However, a higher concentration of GA caused withering of floral buds. Hu et al. (2017) isolated the JcGA2ox6 (Gibberellin oxidase) gene, which reduces the amount of endogenous GA4 (active gibberellin). They overexpressed JcGA2ox6 gene in Jatropha, which led to decreased inflorescence size, decreased male and female flowers, and decreased seed length in transgenic plants. There was a significant decrease in both seed weight and oil content. GA20ox and GA3ox have been observed in other studies to enhance the development of stamen, whereas the exogenous application of GA3 led to a restricted development of pistils, thus enabling the male to expand. GA treatment enhanced the development of stamens in monoecious females, and it resulted in bisexual flowers in monoecious plants. GASA4 protein functions in stamen differentiation. GID1, a positive GA signaling pathway regulator, controls Jatropha’s female flowering (Roxrud et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2017). GA deficiency results in male sterility in plants. Therefore, GA allows the stamens to develop without affecting female flowers.

Paclobutrazol foliar application inhibits GA biosynthesis and promotes female flowering by suppressing no related pollen germination (JcNPGR2), male defective gametophyte (JcMGP2/3), duo pollen (JcDUO3), and male sterility protein (JcMS) genes, thus allowing female flowers to develop in Jatropha (Seesangboon et al., 2018).

Jasmonic acids and brassinosteroids (BRs) are active in floral development together with stamen development, pollen maturation, and male fertility (Park et al., 2002; Ye et al., 2010). In staminate maize flowers, brassinosteroids promoted pistil abortion. AG controls the maturation and late stages of stamen development in Arabidopsis by regulating the biosynthesis of jasmonates (Ito et al., 2007). Reduced JA synthesis in Jatropha led to male abortion and downregulation of the genes DAD1 and LOX2. Arabidopsis, maize, and tomato mutants with suppressed jasmonate synthesis and brassinosteroid signaling resulted in male sterility (Li et al., 2005; Ye et al., 2010). The SPL/NZZ, Aborted Microspores (AMS) and Defective in Tapetal Development and Function 1 (TDF1) genes are regulated by BRs and are critical for anther and pollen development (Ye et al., 2010). Thus, BRs and JAs promote the development of male organs.

Foliar application of ethylene induced femininity in Jatropha. To synthesize ethylene, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid oxidase 2 (ACO1) oxidizes ethylene intermediates. Transgenics plants that overexpressed ACO2 were male sterile due to suppressed stamens. Little to no activity of ACO was observed in Arabidopsis, tomato, and tobacco during the development of anthers and pollens (Bartley and Ishida, 2007; Duan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2010). These experiments have thus shown that ethylene promotes feminism in plants.

Studies have been conducted to see the effect of foliar cytokinin application on the inflorescences. It has been found that 29.99 percent of the total flowers were females in treated inflorescences as compared to 6.96 percent in control. In treated inflorescence, a 4–5-fold increase in the number of seeds was observed but the fruiting rate, seed weight, and oil content decreased (Pan and Xu, 2011; Pan et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2014).

Transcriptomic analysis of Jatropha inflorescences treated with cytokinin revealed that genes involved in the initiation of flowers, such as GI, SOC1, and LFY, and the CYP89A5 gene involved in the development of inflorescences were induced, whereas the AP1, AP2, PI, AG, and SEP1-3 genes were downregulated (Chen et al., 2014; Pan et al., 2014). These developments allowed more time for inflorescence meristems to generate floral primordia. A vital increase in the number of flowers was noted due to CUC1 upregulation. Application of BA (6-Benzylaminopurine) increased the rate of cell division in inflorescence meristem due to the upregulation of Cyclin-3-1 (CycD3;1/2) and Cyclin-dependent protein kinase 247 (CycA3;2) genes. Li et al. (2010) observed an increase in the number of flowers with an enlarged inflorescence and floral meristem in transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing CK (cytokinin) biosynthetic gene (AtIPT4). Fewer flowers were observed at each inflorescence due to the overexpression of the CKX gene (Werner and Schmülling, 2009). Loss-of-function mutation of LONELY GUY (LOG) (encodes for CK-activating enzyme) gene of rice led to the significant decrease in the number of floral organs (Kurakawa et al., 2007). Chen et al. (2014) reported that BA treatment decreased the expression of TS2, which suppresses carpel in maize, leading to increased female to male flower ratios in Jatropha (Acosta et al., 2009).

Challenges

Genomic studies on flowering of Jatropha and phenotypic changes following the application of PGRs (Plant Growth Regulators) showed an opportunity to increase female flowering, which is one of the aspects for increasing seed yields. There are several challenges to increasing a number of female flowers: (i) manual hormone application to each inflorescence is laborious; (ii) hormone application is not economical; (iii) optimized hormone concentration at one environmental condition may not show the same efficiency under different environmental conditions; (iv) flowering and fruit maturity are not synchronized; and the (v) variation in fruiting rate. Genetic modification of flowering genes or overexpression of genes involved in suppression of male flowers may enable us to overcome these challenges by allowing more female flowers to develop. Other possibilities include enhancing cytokinin synthesis by overexpressing genes associated with cytokinin biosynthesis or suppressing cytokinin breakdown by gene silencing or mutagenesis. Additionally, further research could be carried out on the effect of central carbon flow on the fruiting rate.

Conclusion and Perspective

The female to male floral ratio plays a significant role in deciding Jatropha’s seed yield. Cytokinin application showed promising results in enhancing the ratio between female and male flowers. Promising approaches to increase the number of female flowers may be to induce the transitioning of male type inflorescences to the middle/intermediate type or to increase male flower abortion rates to allow female flowers to develop. Therefore, genes involved in female flowering or the abortion of male flowers could be targeted for the purpose of increasing female flowers in Jatropha.

Author Contributions

MG and JS conceived and designed the review manuscript, wrote, read, and approved the manuscript. JS contributed materials or analytical tools and supervised the work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the Department of Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, Jaypee University of Information Technology, Solan, India, for the providing facilities.

Abbreviations

- BRs

brassinosteroids

- CTK

cytokinin

- GAs

gibberellic acids

- JAs

jasmonic acid

- Jatropha

Jatropha curcas L.

Footnotes

References

- Abdelgadir H. A., Jager A. K., Johnson S. D., Van S. J. (2010). Influence of plant growth regulators on flowering, fruiting, seed oil content, and oil quality of Jatropha curcas. South Afr. J. Bot. 76 440–444. [Google Scholar]

- Achten W. M. J., Verchot L., Franken Y. J., Mathijs E., Singh V. P., Aerts R., et al. (2008). Jatropha bio-diesel production and use. Biomass Bioenergy 32 1063–1084. 10.1016/j.biombioe.2008.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta I. F., Laparra H., Romero S. P., Schmelz E., Hamberg M., Mottinger J. P., et al. (2009). Tasselseed1 is a lipoxygenase affecting jasmonic acid signaling in sex determination of maize. Science 323 262–265. 10.1126/science.1164645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam H., Jouannic S., Morcillo F., Verdeil J. L., Duval Y., Tregear J. W. (2007). Determination of flower structure in elaeisguineensis: do palms use the same homeotic genes as other species? Ann. Bot. 100 1–12. 10.1093/aob/mcm027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adriano-Anaya M de. L., Pérez-Castillo E., Salvador-Figueroa M., Ruiz-González S., Vázquez-Ovando A., Grajales-Conesa J., et al. (2016). Sex expression and floral diversity in Jatropha curcas: a population study in its center of origin. PeerJ 4:e2071. 10.7717/peerj.2071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth C. (1999). Sex Determination in Plants. Oxford: BIOS Scientific Publishers [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth C. (2000). Boys and girls come out to play: the molecular biology of dioecious plants. Ann. Bot. 86 211–221. 10.1006/anbo.2000.1201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez J., Smyth D. R. (1999). CRABS CLAW and SPATULA, two Arabidopsis genes that control carpel development in parallel with AGAMOUS. Development 126 2377–2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley G. E., Ishida B. K. (2007). Ethylene-sensitive and insensitive regulation of transcription factor expression during in vitro tomato sepal ripening. J. Exp. Bot. 58 2043–2051. 10.1093/jxb/erm075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentolila S., Alfonso A. A., Hanson M. R. (2002). A pentatricopeptide repeat-containing gene restores fertility to cytoplasmic male-sterile plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 10887–10892. 10.1073/pnas.102301599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownfield L., Hafidh S., Durbarry A., Khatab H., Sidorova A., Doerner P., et al. (2009). Arabidopsis DUO POLLEN3 is a key regulator of male germline development and embryogenesis. Plant Cell 21 1940–1956. 10.1105/tpc.109.066373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner A. M., Rottmann W. H., Sheppard L. A., Krutovskii K., DiFazio S. P., Leonardi S., et al. (2000). Structure and expression of duplicate AGAMOUS orthologues in poplar. Plant Mol. Biol. 44 619–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchetti V., Altamura M. M., Falasca G., Costantino P. P., Cardarelli M. (2008). Auxin regulates Arabidopsis anther dehiscence, pollen maturation, and filament elongation. Plant Cell 20 1760–1774. 10.1105/tpc.107.057570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. S., Pan B. Z., Fu Q., Tao Y. B., Martínez-Herrera J., Niu L., et al. (2017). Comparative transcriptome analysis between gynoecious and monoecious plants identifies regulatory networks controlling sex determination in Jatropha curcas. Front Plant Sci. 7:1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. S., Pan B. Z., Wang G. J., Ni J., Niu L., Xu Z. F. (2014). Analysis of the transcriptional responses in inflorescence buds of Jatropha curcas exposed to cytokinin treatment. BMC Plant Biol. 14:318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-T., Chang C.-C., Chen C.-W., Chen K.-C., Chu Y.-W. (2019). MADS-Box gene classification in angiosperms by clustering and machine learning approaches. Front Genet. 9:707. 10.3389/fgene.2018.00707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Dai X., Zhao Y. (2006). Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases controls the formation of floral organs and vascular tissues in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 20 1790–1799. 10.1101/gad.1415106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Z., Yuan M., Yao J., Ge X., Yuan B., Xu C., et al. (2006). Promoter mutations of an essential gene for pollen development result in disease resistance in rice. Genes Dev. 20 1250–1255. 10.1101/gad.1416306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y., Wang W., Li W. Q., Xia C., Liao H. Z., Zhang X. Q., et al. (2010). MALE GAMETOPHYTE DEFECTIVE 2, encoding a sialyltransferase-like protein, is required for normal pollen germination and pollen tube growth in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 52 829–843. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00963.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Q., Wang D., Xu Z., Bai S. (2008). Stamen development in Arabidopsis is arrested by organ-specific overexpression of a cucumber ethylene synthesis gene CsACO2. Planta 228 537–543. 10.1007/s00425-008-0756-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaro R., Pinyopich A., Battaglia R., Kooiker M., Borghi L., Dittam G., et al. (2003). MADS-box protein complexes control carpel and ovule development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15 2603–2611. 10.1105/tpc.015123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangwar M., Shankar J., Chauhan R. S. (2018). Genomics of Female Flowering and Seed Yield in Jatropha Curcas L. Ph.D. Thesis, Jaypee University of Information Technology, Solan. [Google Scholar]

- Golovkin M., Reddy A. S. (2003). A calmodulin-binding protein from Arabidopsis has an essential role in pollen germination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 10558–10563. 10.1073/pnas.1734110100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross T., Broholm S., Becker A. (2018). CRABS CLAW acts as a bifunctional transcription factor in flower development. Front. Plant Sci. 9:835. 10.3389/fpls.2018.00835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J., Liu C., Wang P., Cheng Q., Sun L., Yang W., et al. (2018). The aborted microspores (AMS)-like gene is required for anther and microspore development in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:1341. 10.3390/ijms19051341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma T., Goto K. (2001). Complexes of MADS-box proteins are sufficient to convert leaves into floral organs. Nature 409 525–529. 10.1038/35054083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y. X., Tao Y. B., Xu Z. F. (2017). Overexpression of Jatropha Gibberellin 2-oxidase 6 (JcGA2ox6) induces dwarfism and smaller leaves, flowers and fruits in Arabidopsis and Jatropha. Front. Plant Sci. 8:2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Li Z., Zhao D. (2016). Deregulation of the OsmiR160 target gene OsARF18 causes growth and developmental defects with an alteration of auxin signaling in rice. Sci. Rep. 6:29938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui W., Yang Y., Wu G., Peng C., Chen X., Zayed M. Z. (2017). Transcriptome profile analysis reveals the regulation mechanism of floral sex differentiation in Jatropha curcas L. Sci. Rep. 7:16421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui W. K., Wang Y., Chen X. Y., Zayed M. Z., Wu G. J. (2018). Analysis of transcriptional responses of the inflorescence meristems in Jatropha curcas following gibberellin treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:432. 10.3390/ijms19020432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi T. (2010). Arabidopsis circadian clock and photoperiodism: time to think about location. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13 83–89. 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Ng K. H., Lim T. S., Yu H., Meyerowitz E. M. (2007). The homeotic protein AGAMOUS controls late stamen development by regulating a jasmonate biosynthetic gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19 3516–3529. 10.1105/tpc.107.055467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi G., Shukla A., Shukla A. (2011). Synergistic response of auxin and ethylene on physiology of Jatropha curcas L. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 23 66–77. 10.1590/s1677-04202011000100009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karlgren A., Gyllenstrand N., Clapham D., Lagercrantz U. (2013). FLOWERING LOCUS T/TERMINAL FLOWER1-like genes affect growth rhythm and bud set in Norway spruce. Plant Physiol. 163 792–803. 10.1104/pp.113.224139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kater M. M., Franken J., Carney K., Colombo L., Angenent G. C. (2001). Sex determination in the monoecious species cucumber is confined to specific floral whorls. Plant Cell 13 481–493. 10.1105/tpc.13.3.481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Sharma S. (2008). An evaluation of multipurpose oil seed crop for industrial uses (Jatropha curcas L): a review. Ind. Crops Prod. 28 1–10. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2008.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurakawa T., Ueda N., Maekawa M., Kobayashi K., Kojima M., Nagato Y., et al. (2007). Direct control of shoot meristem activity by a cytokinin-activating enzyme. Nature 445:652. 10.1038/nature05504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leseberg C. H., Li A. L., Kang H., Duvall M., Mao L. (2006). Genome-wide analysis of the MADS-box gene family in Populus trichocarpa. Gene 378 84–94. 10.1016/j.gene.2006.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Fu Q., Niu L., Luo L., Chen J., Xu Z. F. (2017). Three TFL1 homologues regulate floral initiation in the biofuel plant Jatropha curcas. Sci. Rep. 7:43090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Luo L., Fu Q., Niu L., Xu Z. F. (2014). Isolation and functional characterization of JcFT, a flowering LOCUS T (FT) homologous gene from the biofuel plant Jatropha curcas. BMC Plant Biol. 14:125. 10.1186/1471-2229-14-125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Schilmiller A. L., Liu G., Lee G. I., Jayanty S., Sageman C., et al. (2005). Role of β-oxidation in jasmonate biosynthesis and systemic wound signaling in tomato. Plant Cell 17 971–986. 10.1105/tpc.104.029108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Li Q. (2009). The correlationship between flowering sequence and floral gender in the inflorescence of Jatropha curcas L. (Euphorbiaceae). J. Trop. Subtrop. Bot. 17 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Li X. G., Su Y. H., Zhao X. Y., Li W., Gao X. Q., Zhang X. S. (2010). Cytokinin overproduction caused alteration of flower development is partially mediated by CUC2 and CUC3 in Arabidopsis. Gene 450 109–120. 10.1016/j.gene.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Huang J., Parameswaran S., Ito T., Seubert B., Auer M., et al. (2009). The SPOROCYTELESS/NOZZLE gene is involved in controlling stamen identity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 151 1401–1411. 10.1104/pp.109.145896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C., Li K., Chen Y., Yong S. (2007). Floral display and breeding system of Jatropha curcas L. Forest Stud. China 9 114–119. 10.1007/s11632-007-0017-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maier A. T., Stehling-Sun S., Wollmann H., Demar M., Hong R. L., Haubeiss S., et al. (2009). Dual roles of the bZIP transcription factor PERIANTHIA in the control of floral architecture and homeotic gene expression. Development 136 1613–1620. 10.1242/dev.033647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makkena S., Lee E., Sack F. D., Lamb R. S. (2012). The R2R3 MYB transcription factors four lips and myb88 regulate female reproductive development. J. Exp. Bot. 63 5545–5558. 10.1093/jxb/ers209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Fernández I., Sanchís S., Marini N., Balanzá V., Ballester P., Navarrete-Gómez J., et al. (2014). The effect of NGATHA altered activity on auxin signaling pathways within the Arabidopsis gynoecium. Front. Plant Sci. 5:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi T., Wright L., Fujiwara S., Cremer F. (2005). Coupland, distinct roles of GIGANTEA in promoting flowering and regulating circadian rhythms in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17 2255–2270. 10.1105/tpc.105.033464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T., Schuster G., Sugiura M., Sugita M. (2004). Chloroplast RNA binding and pentatricopeptide repeat proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32 571–574. 10.1042/bst0320571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan B. Z., Xu Z. F. (2011). Benzyladenine treatment significantly increases the seed yield of the biofuel plant Jatropha curcas. J. Plant Growth Regul. 30, 166–174. 10.1007/s00344-010-9179-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan B. Z., Chen M. S., Ni J., Xu Z. F. (2014). Transcriptome of the inflorescence meristems of the biofuel plant Jatropha curcas treated with cytokinin. BMC Genomics 15:974. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. H., Halitschke R., Kim H. B., Baldwin I. T., Feldmann K. A., Feyereisen R. (2002). A knock-out mutation in allene oxide synthase results in male sterility and defective wound signal transduction in Arabidopsis due to a block in jasmonic acid biosynthesis. Plant J. 31 1–12. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01328.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parěnicová L., de Folter S., Kieffer M., Horner D. S., Favalli C., Busscher J., et al. (2003). Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of the complete MADS-box transcription factor family in Arabidopsis: new openings to the MADS world. Plant Cell 15 1538–1551. 10.1105/tpc.011544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelaz S., Ditta G. S., Baumann E., Wisman E., Yanofsky M. F. (2000). B and C floral organ identity functions require SEPALLATA MADS-box genes. Nature 405 200–203. 10.1038/35012103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinyopich A., Ditta G. S., Savidge B., Liljegren S. J., Baumann E., Wisman E., et al. (2003). Assessing the redundancy of MADS-box genes during carpel and ovule development. Nature 424 85–88. 10.1038/nature01741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prunet N., Yang W., Das P., Meyerowitz E. M., Jack T. P. (2017). SUPERMAN prevents class B gene expression and promotes stem cell termination in the fourth whorl of Arabidopsis thaliana flowers. PNAS 114 7166–7171. 10.1073/pnas.1705977114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos M. J. N., Coito J. L., Silva H. G., Cunha J., Costa M. M. R., Rocheta M. (2014). Flower development and sex specification in wild grapevine. BMC Genomics 15:1095. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Concepción M., Beltrán J. P. (1995). Repression of the pea lipoxygenase gene loxg is associated with carpel development. Plant Mol. Biol. 27 887–899. 10.1007/bf00037017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roxrud I., Lid S. E., Fletcher J. C., Schmidt E. D., Opsahl-Sorteberg H. G. (2007). GASA4, one of the 14-member Arabidopsis GASA family of small polypeptides, regulates flowering and seed development. Plant Cell Physiol. 48 471–483. 10.1093/pcp/pcm016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-Figueroa M., Magaña-Ramos J., Vázquez-Ovando J. A., Adriano-Anaya M. L., Ovando-Medina I. (2015). Genetic diversity and structure of Jatropha curcas L. in its centre of origin. Plant Genet Resourc. 13, 9–17. 10.1017/S1479262114000550 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seesangboon A., Gruneck L., Pokawattana T., Eungwanichayapant P. D., Tovaranonte J., Popluechai S. (2018). Transcriptome analysis of Jatropha curcas L. flower buds responded to the paclobutrazol treatment. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 127 276–286. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafiee S., Topal E. (2009). When will fossil fuel reserves be diminished? Energy Pol. 37 181–189. 10.1016/j.enpol.2008.08.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova A. N., Robertson-Hoyt J., Yun J., Benavente L. M., Xie D.-Y., Dolezal K., et al. (2008). TAA1-mediated auxin biosynthesis is essential for hormone crosstalk and plant development. Cell 133, 177––191. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova A. N., Yun J., Robles L. M., Novak O., He W., Guo H., et al. (2011). The Arabidopsis YUCCA1 flavin monooxygenase functions in the indole-3-pyruvic acid branch of auxin biosynthesis. Plant Cell 23 3961–3973. 10.1105/tpc.111.088047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Switzenberg J., Little H., Hammar S., Grumet R. (2014). Floral primordia-targeted ACS (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase) expression in transgenic Cucumis melo implicates fine tuning of ethylene production mediating unisexual flower development. Planta 240 797–808. 10.1007/s00425-014-2118-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M., Tao Y. B., Fu Q., Song Y., Niu L., Xu Z. F. (2016). An ortholog of LEAFY in Jatropha curcas regulates flowering time and floral organ development. Sci. Rep. 6:37306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Nakajima M., Katoh E., Ohmiya H., Asano K., Saji S., et al. (2007). Molecular interactions of a soluble gibberellin receptor, GID1, with a Rice DELLA protein, SLR1, and gibberellins. Plant Cell 19 2140–2155. 10.1105/tpc.106.043729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. H., Li F., Duan Q. H., Han T., Xu Z. H., Bai S. N. (2010). Ethylene perception is involved in female cucumber flower development. Plant J. 61 862–872. 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2009.04114.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner T., Schmülling T. (2009). Cytokinin action in plant development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12 527–538. 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Liu Y., Tang L., Zhang F., Chen F. (2011). A study on structural features in early flower development of Jatropha curcas L. and the classification of its inflorescence. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 6 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Xu G., Huang J., Yang Y., Yao Y. A. (2016). Transcriptome analysis of flower sex differentiation in Jatropha curcas L. using RNA sequencing. PLoS One 11:e0145613. 10.1371/journal.pone.0145613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Prunet N., Gan E. S., Wang Y., Stewart D., Wellmer F. (2018). SUPERMAN regulates floral whorl boundaries through control of auxin biosynthesis. EMBO J. 37:e97499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaki S., Nagato Y., Kurata N., Nonomura K. (2011). Ovule is a lateral organ finally differentiated from the terminating floral meristem in rice. Dev. Biol. 351 208–216. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Yang M. F., Wen P. Z., Fan C., Shen S. H. (2011). A putative flowering-time- related Dof transcription factor gene, JcDof3, is controlled by the circadian clock in Jatropha curcas. Plant Sci. 181 667–674. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J., Geng Y., Zhang B., Mao H., Qu J., Chua N. H. (2014). The jatropha FT ortholog is a systemic signal regulating growth and flowering time. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 7:91. [Google Scholar]

- Ye Q., Zhu W., Li L., Zhang S., Yin Y., Ma H., et al. (2010). Brassinosteroids control male fertility by regulating the expression of key genes involved in Arabidopsis anther and pollen development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 6100–6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Chen H., Li H., Gao J. F., Jiang H., Wang C., et al. (2008). Defective in tapetal development and function 1 is essential for anther development and petal function for microspore maturation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 55 266–277. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03500.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]