Abstract

BACKGROUND:

We evaluated associations between perceived social support, social integration, living alone, and colorectal cancer (CRC) outcomes in postmenopausal women.

METHODS:

The study included 1431 women from the Women’s Health Initiative who were diagnosed from 1993 through 2017 with stage I through IV CRC and who responded to the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support survey before their CRC diagnosis. We used proportional hazards regression to evaluate associations of social support (tertiles) and types of support, assessed up to 6 years before diagnosis, with overall and CRC-specific mortality. We also assessed associations of social integration and living alone with outcomes also in a subset of 1141 women who had information available on social ties (marital/partner status, community and religious participation) and living situation.

RESULTS:

In multivariable analyses, women with low (hazard ratio [HR], 1.52; 95% CI, 1.23–1.88) and moderate (HR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.98–1.50) perceived social support had significantly higher overall mortality than those with high support (P [continuous] < .001). Similarly, women with low (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.07–1.88) and moderate (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 0.96–1.70) perceived social support had higher CRC mortality than those with high social support (P [continuous] = .007). Emotional, informational, and tangible support and positive interaction were all significantly associated with outcomes, whereas affection was not. In main-effects analyses, the level of social integration was related to overall mortality (P for trend = .02), but not CRC mortality (P for trend = .25), and living alone was not associated with mortality outcomes. However, both the level of social integration and living alone were related to outcomes in patients with rectal cancer.

CONCLUSIONS:

Women with low perceived social support before diagnosis have higher overall and CRC-specific mortality.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, social networks, social support, social ties, women

INTRODUCTION

Social support is the perception and reality of the exchange of assistance through social relationships.1 Social networks (SNs) are defined as the web of social ties that surround an individual1; SN size and social integration, defined as the degree to which people are engaged with society, are often used interchangeably. Social isolation is defined as few SN ties or little contact with those ties, although living alone has often been used as a proxy in research and in clinical care settings. SNs, social ties, social integration, and social isolation are measures of structural social support, whereas social support, also called functional social support, may be provided through SNs.2

Substantial literature has demonstrated that women with larger SNs and greater social support have longer breast cancer survival.3–8 Although colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in the United States, and social support is considered to have an important influence on cancer survival generally,2 exceedingly little work has examined the influence of social support on CRC outcomes. This is caused in part by the lack of large CRC cohorts with social data and sufficient follow-up to examine social variables and mortality outcomes. In a study of 294 patients, 26% of whom had CRC, social ties and social support were unrelated to survival in the combined subset of patients who had lung cancer and CRC.9 In the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) (N = 896), women who were more socially integrated had longer CRC survival; however, there was no association between the presence of a confidant, the investigators’ proxy measure of social support, and CRC survival.10 Being married has been associated with better survival in patients with CRC.11–15 Living alone was associated with worse survival in Scandinavian patients with metastatic CRC.16 Although associations of social support, SNs, and CRC outcomes might parallel associations seen in patients with breast cancer, associations may differ by type of cancer. Differences may be due to differential types and invasiveness of treatment, needs for support, and caregiving burdens among those who provide support,17 particularly given findings showing large declines in support in a substantial fraction of patients with CRC in the 2 years after diagnosis related to patient comorbidities or a stoma.17

Therefore, we examined associations of social support using the well established Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) social support measure and CRC survival (overall and disease-specific mortality) in a large population of postmenopausal women from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). Specifically, we examined how women’s reserves of support before diagnosis may influence CRC outcomes. We also examined associations of social ties and living status with outcomes and further examined whether factors such as disease severity, depressive symptomatology, and lifestyle factors mediated those associations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

The design of the WHI has been previously described.18,19 Briefly, the WHI observational study is a multiethnic cohort of 93,676 postmenopausal women, ages 50 to 79 years, who were enrolled during 1993 through 1998 at 40 geographically diverse clinical centers throughout the United States. Eligibility criteria included: 1) ages 50 to 79 years, 2) postmenopausal status, 3) willingness to provide informed consent, and 4) at least a three-year life expectancy. The WHI clinical trials study includes 68,132 women with the same basic eligibility who agreed to participate in randomized clinical trials of diet or menopausal hormone therapy. Recruitment methods are detailed elsewhere.20

We selected into the cohort women who were diagnosed with any stage primary CRC between study enrollment and study end in February 2017 (n = 2906) who completed social measures within 6 years before CRC diagnosis (N = 1858). To clarify, women from the WHI provided information on social measures at 3 timepoints; women from both the observational study and the clinical trials study provided information at study baseline and again in 2011 and 2012 for those who agreed to participate in the WHI Extension Study II. Women from the clinical trials study also completed social measures at the close of the initial WHI study, approximately 10 years after the baseline assessment. This meant that the cohort consisted of 3 WHI subcohorts—those diagnosed within 6 years after baseline (N = 903), study closeout (N = 291), or the Extension Study II (N = 237). The cutoff point of 6 years was chosen to balance the tradeoff in maximizing the number of participants in the study and selecting patients with social support measures close in time and before diagnosis. Of these, we excluded women with a history of cancer, except for nonmelanoma skin cancer (N = 281), those missing information on stage or grade (N = 90), and those specifically missing the MOS social support measure (N = 56). Thus we included 1431 women in the study population (mean age, 72 years). Follow-up after a CRC diagnosis ranged from 0 to 21.9 years (median follow-up, 5.8 years). During follow-up, 539 women died, including 327 from CRC. Human subjects review committees at each participating institution approved the protocol, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Data Collection

At baseline, participants provided detailed information about demographics, psychosocial factors, medical history, and known or suspected risk factors for cancer through a self-administered questionnaire. This information included self-reported race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (education, income). Social and psychosocial measures were collected at additional timepoints, as previously described. Medical history was updated annually in the observational study and every 6 months in the clinical trials study (annually in the clinical trials study after 2005), by mail and/or telephone questionnaires. Lifestyle measures (ie, smoking, physical activity, alcohol consumption) were assessed by survey at baseline, in year 9 (among clinical trials study participants), and at year 2 of Extension Study II. Anthropometric measures were collected yearly in clinical trials study participants and at baseline and year 3 in observational study participants. Aspirin and ibuprofen use was assessed by in-person interviews. Age at diagnosis and disease severity (stage, grade, site) were assessed at the time of CRC diagnosis. Treatment data (surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy), collected through the Life and Longevity After Cancer (LILAC) study of women from the WHI diagnosed with cancer, used Medicare data in women who were diagnosed at ages ≥65 years, medical records in those who died before the LILAC study, and a combination of medical records and self-reported data in those living participants with CRC.21 Treatment data were available for 67.5% of women in the study population.

CRC ascertainment

Cancers were initially identified from annual self-report of medical history and then confirmed by medical record and pathology report review (available in 98.2% of participants). All cancers were centrally adjudicated, and characteristics (histology, stage, grade, and site) were coded using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results coding system.22 These analyses were limited to invasive CRCs that were confirmed by central review.

Mortality

Attribution of cause of death was based on medical record review by physician adjudicators who were blinded to information about SNs.22 The National Death Index was searched at 2-year to 3-year intervals to identify deaths in participants who were lost to follow-up. For CRC cases identified only through the National Death Index, information was limited to death certificates only.

Social support

Social support was assessed within 6 years before diagnosis using 9 items from the MOS questionnaire.23 On a 5-point scale, participants ranked how often specific types of support, including emotional support (eg, someone to listen to problems), affection (eg, someone to make a person feel loved), tangible support (eg, help with chores or rides to the doctor), and positive interaction (eg, someone to have fun with), were available. The summary score ranged from 9 to 45 (mean ± SD score, 36.0 ± 8.0), with a higher score indicating more social support. Internal consistency for the score was high (standardized Cronbach α = .94). No clinically meaningful categories exist for the MOS social support scale,24 so we categorized social support into tertiles based on the distribution of women in this study.

Social integration (SN size) and social ties

SN members (social ties) included a spouse or intimate partner, club ties, and religious ties. Women were asked, “Are you currently married or in an intimate relationship with at least 1 person?” Women were also asked, “How often have you gone to meetings of clubs, lodges, or parent groups in the last month?” and, “How often have you gone to a religious service or to church during the past month?” For these questions, response options included: 1) not at all in the past month, 2) once in the past month, 3) 2 or 3 times in the past month, 4) once a week, 5) 2 to 6 times a week, and 6) every day. To compute a proxy variable for SN size (ie, our measure of social integration), we dichotomized and summed variables (any [scored 1] vs no [scored 0] religious participation, any [scored 1] vs no [scored 0] community participation, and married/partnered [scored 1] or not [scored 0]) and categorized the resulting variable into 3 groups of similar size. Those with the largest networks were categorized as socially integrated, those in the middle group were categorized as moderately integrated, and those with the smallest networks were categorized as socially isolated. We also analyzed each social tie separately.

Living status

Women were asked whether they lived alone or with a family member, friend, or pet. We specifically focused on whether women lived alone versus with (an)other person(s).

Covariates

Study (clinical trials study vs observational study) was determined at baseline. We computed lag time as the time between social assessment and CRC diagnosis. Family history of CRC, lifestyle and related factors (body mass index [BMI], alcohol, physical activity, smoking, aspirin/ibuprofen intake), depressive symptoms, and comorbidity, using the WHI-modified Charlson index,25 were assessed closest in time to social measures. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale.26 Alcohol was measured in drinks per week, and smoking was assessed as current, past, or never. Physical activity was assessed in terms of hours per week of moderate or strenuous physical activity, and weekly recreational physical activity was calculated by multiplying an assigned energy expenditure level for each category of activity by the hours exercised per week to calculate total metabolic equivalents per week.27 BMI (in kg/m2) was derived from information on weight and height. Women also provided information on CRC screening (colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy, fecal occult blood test, barium enema) at 6-month (clinical trials study) or annual (observational study) medical updates; and the information obtained closest to each social measure was used. Aspirin and ibuprofen use was assessed dichotomously (yes/no) using a single indicator variable. Hormone therapy use was assessed at baseline using a single indicator.

Statistical Analyses

We evaluated frequencies or means of variables by tertiles of social support using chi-square and Wald tests (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Patients With Colorectal Cancer From the Women’s Health Initiative, N = 1431a

| Characteristic | Social Supportb |

Pc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Moderate | Low | ||

| Total no. | 485 | 486 | 460 | |

| WHI baseline characteristics, % | ||||

| Observational study participants | 41.4 | 42.8 | 42.4 | .91 |

| Family history of CRC, N = 1311 | 19.2 | 21.9 | 22.7 | .41 |

| Hormone use, N = 1429 | ||||

| Never | 77.3 | 79.8 | 80.4 | .49 |

| Past | 7.2 | 7.0 | 5.0 | |

| Current | 15.5 | 13.2 | 14.6 | |

| Demographic characteristics, % | ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 85.8 | 81.3 | 82.4 | .87 |

| African American | 8.7 | 11.9 | 10.2 | |

| Asian | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.4 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.8 | |

| Other/unknown | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.1 | |

| Education, N = 1420 | ||||

| ≤High school | 22.3 | 24.6 | 23.5 | .77 |

| Some college/vocational school | 43.7 | 39.1 | 39.5 | |

| College graduate | 12.1 | 11.8 | 11.6 | |

| Postgraduate | 22.0 | 24.4 | 25.4 | |

| Household income, N = 1350 | ||||

| <$25,000 | 13.7 | 17.1 | 27.8 | <.001 |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 48.7 | 48.1 | 46.1 | |

| ≥$50,000 | 37.6 | 34.9 | 26.2 | |

| Characteristics at time of diagnosis | ||||

| Age at diagnosis, y | 72.0 | 72.1 | 72.2 | .90 |

| Time from social measure to diagnosis, d | 1052 | 1027 | 1000 | .40 |

| Severity of disease, % | ||||

| Stage and grade | ||||

| In situ/local, well/moderately differentiated | 33.8 | 35.0 | 31.7 | .93 |

| In situ/local, poorly differentiated/anaplastic | 3.9 | 4.7 | 5.7 | |

| Regional, well/moderately differentiated | 28.0 | 27.4 | 30.2 | |

| Regional, poorly differentiated/anaplastic | 12.6 | 13.0 | 10.9 | |

| Distant, well/moderately differentiated | 5.6 | 6.2 | 5.4 | |

| Distant, poorly differentiated/anaplastic | 4.5 | 4.1 | 4.1 | |

| Grading unknown | 11.6 | 9.7 | 12.0 | |

| Site, % | ||||

| Colon cancer | 80.8 | 82.1 | 82.0 | .87 |

| Rectal cancer | 13.0 | 13.2 | 12.2 | |

| Unknown | 6.2 | 4.7 | 5.9 | |

| Surgery, % | ||||

| Yes | 65.0 | 68.7 | 58.5 | .03 |

| No | 5.4 | 4.7 | 6.7 | |

| Unknown | 29.7 | 26.5 | 34.8 | |

| Chemotherapy, % | ||||

| Yes | 27.0 | 29.8 | 25.0 | .11 |

| No | 40.8 | 42.2 | 38.9 | |

| Unknown | 32.2 | 28.0 | 36.1 | |

| Radiation, % | ||||

| Yes | 4.3 | 6.8 | 4.6 | .05 |

| No | 63.9 | 65.0 | 59.1 | |

| Unknown | 31.8 | 28.2 | 36.3 | |

| Characteristics closest to social measures | ||||

| Social support rangeb | 9–34 | 34–41 | 41–45 | |

| Any comorbidity, % | 22.5 | 28.0 | 26.3 | .13 |

| Depressive symptomatology score, N = 1430, % | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.07 | <.001 |

| Lifestyle/behavioral factors | ||||

| Past colonoscopy (N = 1348) | 42.1 | 48.9 | 47.9 | .09 |

| Moderate/strenuous exercise, N = 1289 | ||||

| 0 h/wk | 52.3 | 53.9 | 57.0 | .03 |

| 1–2 h/wk | 16.4 | 21.1 | 20.7 | |

| ≥3 h/wk | 31.3 | 25.0 | 22.3 | |

| Smoking, N = 1407 | ||||

| Never | 71.6 | 65.7 | 59.6 | <.001 |

| Past | 25.9 | 30.1 | 32.1 | |

| Current | 2.5 | 4.2 | 8.4 | |

| BMI, N = 1379 | ||||

| <25 kg/m2 | 31.6 | 30.6 | 30.2 | .86 |

| 25 to <30 kg/m2 | 34.6 | 36.8 | 34.2 | |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 33.8 | 32.6 | 35.6 | |

| Alcohol intake, N = 1421 | ||||

| None/past | 33.5 | 34.0 | 33.6 | .69 |

| 1 to <7 drinks or d/wk | 53.4 | 55.2 | 56.1 | |

| Daily or >7 d | 13.1 | 10.8 | 10.3 | |

| Recent aspirin or ibuprofen use | 14.9 | 17.5 | 17.0 | .50 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CRC, colorectal cancer; WHI, Women’s Health Initiative.

There were 1431 study participants unless otherwise indicated.

Values shown indicate tertiles of social support using the Medical Outcomes Study social support measure.

P values were determined using the chi-square test or the Wald test.

Analyses of social variables and mortality outcomes

We used Cox proportional hazards models (SAS PROC PHREG, SAS version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc) for failure-time data to assess associations of social support, types of social support, social integration, social ties, and living status with the time to overall mortality and disease-specific mortality,28,29 considering the competing risks of mortality from other causes. Although a key interest was to examine CRC-specific mortality, we examined all-cause mortality both because examination of this outcome overcomes concerns about bias in the assignment of cause and because overall mortality is an important outcome in and of itself. Person-years of follow-up were measured from the date of diagnosis until the date of death, loss to follow-up, or the end of follow-up, which-ever came first. We conducted tests for linear trend using continuous variables and computed Wald statistics.

Minimally-adjusted models were adjusted for age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity, study arm (clinical trials study vs observational study), time between social assessment and CRC diagnosis, stage, and grade (model 1). Because of strong overlap between stage and grade, we combined these variables into a single variable; categories with similar mortality risk were further combined. We also generated cumulative mortality curves for minimally adjusted associations of social support and overall and disease-specific mortality outcomes. Analyses in model 2 were adjusted additionally for family history of CRC, education, income, comorbidity, and cancer site. Covariates included those that were considered a priori to be important potential confounders of the association between SNs and CRC mortality.

We considered separate models to determine whether 1) depressive symptoms, 2) treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy), or 3) lifestyle/behavioral factors (alcohol, BMI, exercise, smoking, aspirin or ibuprofen use, hormone therapy at baseline, CRC screening) mediated associations. However, given few differences in the results between mediation models, we presented one model that was adjusted for all possible mediators (model 3). We allowed missing categories for covariates in the analyses.

Stratified analyses

We evaluated effect modification by age (< or ≥ median = 72.3 years) at diagnosis, race/ethnicity (non-Latina white or not non-Latina white), education (less than a college degree vs a college degree or greater), family history of CRC (no, yes), stage (in situ/local vs regional/distant), presence of comorbidity (no, yes), cancer site (colon, rectal), smoking behavior (ever vs never), social strain (<median vs ≥median), and provision of caregiving (no, yes). When associations differed across strata, we used Wald tests to evaluate interaction terms of dichotomous stratification variables and either continuous or dichotomous variables, as indicated. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and the criterion for statistical significance was P < .05.

RESULTS

Women with low levels of support reported lower income levels, were more likely to be current smokers, and had greater depressive symptomatology. However, levels of social support were unrelated to age at diagnosis, lag time between social measure to diagnosis, race/ethnicity, education, study arm, family history of CRC, comorbidity, cancer site, stage, tumor grade, CRC screening, use of hormone therapy, aspirin/ibuprofen use, BMI, alcohol use, moderate/strenuous physical activity, or BMI (Table 1).

Main-Effects Analyses

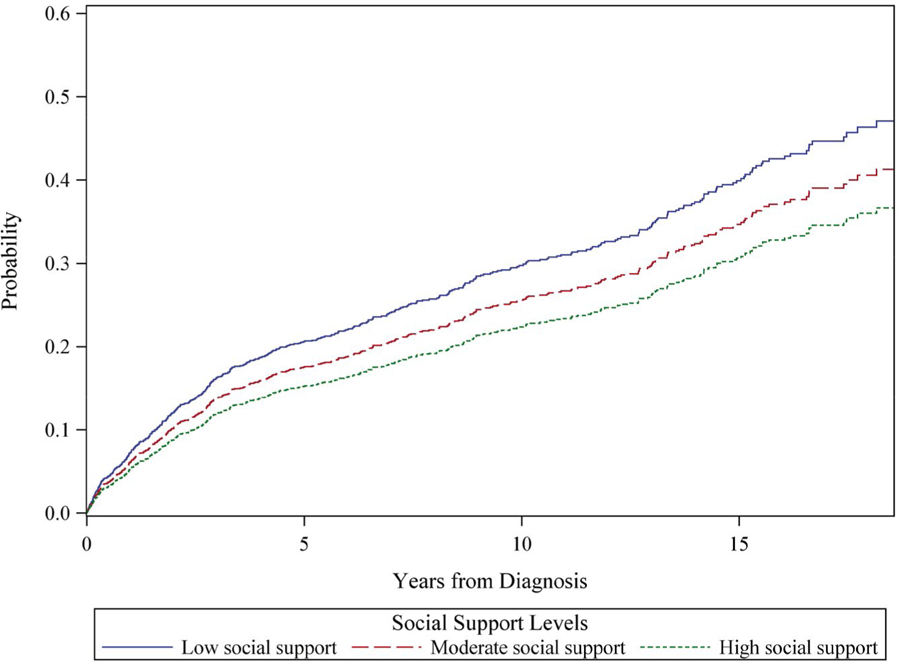

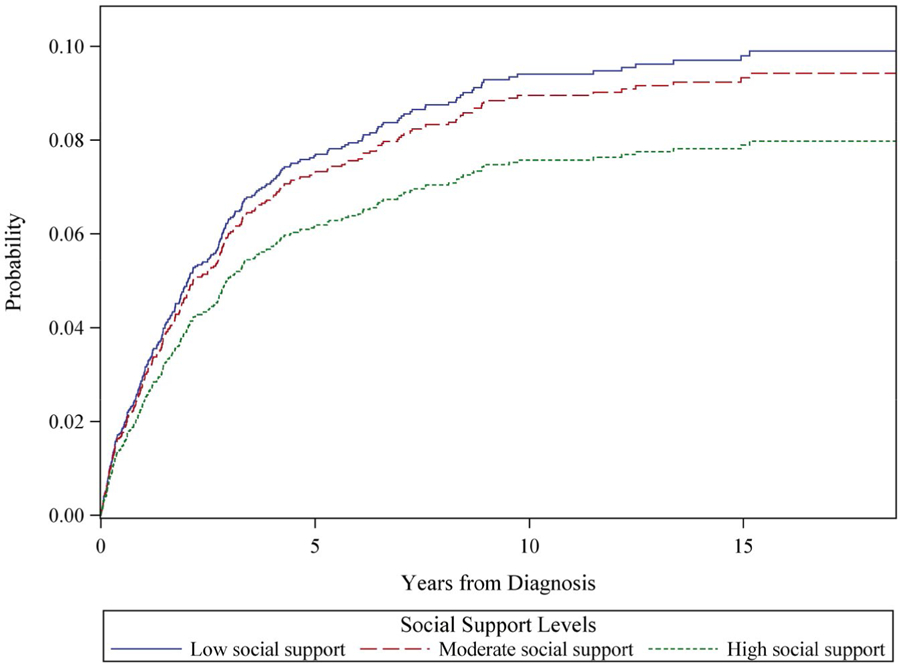

In minimally adjusted (Figs. 1 and 2, Table 2) and multivariable-adjusted (Table 2) models, women with low levels of social support had higher overall mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 1.52; 95% CI, 1.23–1.88) and CRC-specific mortality (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.07–1.88). In Figure 1, overall mortality curves reveal a consistent separation across social support categories over follow-up. In Figure 2, we note a large separation between those who had high support versus those who had low or moderate support in terms of CRC-specific mortality, with the steepest rise in mortality observed during the first 5 years after diagnosis. In associations adjusted for possible mediating factors, associations with overall and CRC mortality were only slightly attenuated (Table 2). Regarding specific types of social support, tangible, emotional, and informational support, as well as positive interaction were each inversely related to outcomes; affection, however, was unrelated to outcomes (Supporting Table 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative total mortality is illustrated among 1431 participants from the Women’s Health Initiative who were diagnosed with colorectal cancer, by tertile of social support. The model is adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), time between social assessment and diagnosis (continuous), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white [reference category], African-American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, other), and stage and grade (local [reference category], regional, distant and well differentiated/moderately differentiated, distant and nondifferentiated/anaplastic).

Figure 2.

Cumulative colorectal-specific cancer mortality is illustrated among 1431 participants from the Women’s Health Initiative who were diagnosed with colorectal cancer, by tertile of social support. The model is adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), time between social assessment and diagnosis (continuous), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white [reference category], African-American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, other), and stage and grade (local [reference category], regional, distant and well differentiated/moderately differentiated, distant and nondifferentiated/anaplastic).

TABLE 2.

Relative Hazards of Mortality by Level of Social Support Among Women in the Women’s Health Initiative Diagnosed With Colorectal Cancer, N = 1431

| Characteristic | Social Supporta |

Pb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Moderate | Low | ||

| No. of women | 485 | 486 | 460 | |

| Social support, range | 9–34 | 34–41 | 41–45 | |

| Overall mortality, no. | 183 | 205 | 228 | |

| Model 1: HR (95% CI)c | 1.00 | 1.20 (0.97–1.49) | 1.49 (1.20–1.83) | <.001 |

| Model 2: HR (95% CI)d | 1.00 | 1.21 (0.98–1.50) | 1.52 (1.23–1.88) | <.001 |

| Model 3: HR (95% CI)e | 1.00 | 1.17 (0.94–1.46) | 1.42 (1.14–1.77) | .003 |

| CRC-specific mortality, no. | 119 | 138 | 142 | |

| Model 1: HR (95% CI)c | 1.00 | 1.24 (0.94–1.64) | 1.36 (1.03–1.80) | .01 |

| Model 2: HR (95% CI)d | 1.00 | 1.28 (0.96–1.70) | 1.42 (1.07–1.88) | .007 |

| Model 3: HR (95% CI)e | 1.00 | 1.27 (0.96–1.69) | 1.37 (1.02–1.84) | .01 |

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; HR, hazard ratio.

Values shown indicate tertiles of social support using the Medical Outcomes Study social support measure.

P values were used from continuous measures of social support.

Model 1 was a minimally adjusted model and was adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), time between social assessment and diagnosis (continuous), study (clinical trial, observational study), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white [reference category], African-American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, other), and stage and grade (local [reference category], regional, distant and well differentiated/moderately differentiated, distant and nondifferentiated/anaplastic).

Model 2, which included possible confounding variables, was adjusted for the covariates in model 1 and additionally for site (rectal, colon [reference category]), education (<high school, high school, some college, college degree or greater [reference category]), income (<$20,000, $20,000 to <$50,000, ≥$50,000 [reference category]), family history of colorectal cancer (yes, no [reference category]), and comorbidity (yes, no [reference category]).

Model 3, which considered mediation by depressive symptoms and treatment and lifestyle factors, was adjusted for the covariates in model 2 and was also adjusted for surgery (yes, no [reference category]), chemotherapy (yes, no [reference category]), radiation (yes, no [reference category]), colorectal cancer screening (yes, no [reference category]), depressive symptomatology (continuous), aspirin or ibuprofen use (yes, no [reference category]), use of hormone therapy (yes, no [reference category]), alcohol intake (none [reference category], >0 to <1.7, 1.7 to <15, ≥15 g/day), smoking (never [reference category], past, current), physical activity (0 to <10 [reference category], 10 to <20, ≥20+ metabolic equivalents per week), and body mass index (<18.5, 18.5–25 [reference category]), 25-<30, ≥30 kg/m2).

In analyses of social ties and outcomes, the level of social integration was associated with overall (P [continuous] = .02), but not CRC-specific (P [continuous] = .25), mortality regardless of adjustment for covariates or possible mediators (Table 3). Looking separately by type of social tie, each tie contributed to the overall association with overall mortality, but associations were weak and mostly nonsignificant. Living alone was associated with overall, but not CRC-specific, mortality in minimally adjusted models. After multivariable adjustment, living alone was no longer associated with outcomes regardless of the level of adjustment (Supporting Table 2).

TABLE 3.

Relative Hazards of Mortality by Level of Social Integration Among Women in the Women’s Health Initiative Diagnosed With Colorectal Cancer, N = 1143

| Characteristic | Level of Social Integrationa |

Pb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socially Integrated | Moderately Integrated | Socially Isolated | ||

| No. of women | 273 | 494 | 374 | |

| Overall mortality, no. | 96 | 203 | 170 | |

| Model 1: HR (95% CI)c | 1.00 | 1.20 (0.94–1.54) | 1.36 (1.05–1.76) | .007 |

| Model 2: HR (95% CI)d | 1.00 | 1.18 (0.92–1.52) | 1.32 (1.01–1.71) | .02 |

| Model 3: HR (95% CI)e | 1.00 | 1.14 (0.89–1.48) | 1.27 (0.97–1.66) | .03 |

| CRC-specific mortality, no. | 59 | 135 | 98 | |

| Model 1: HR (95% CI)c | 1.00 | 1.16 (0.86–1.58) | 1.22 (0.88–1.68) | .18 |

| Model 2: HR (95% CI)d | 1.00 | 1.20 (0.88–1.64) | 1.21 (0.87–1.69) | .25 |

| Model 3: HR (95% CI)e | 1.00 | 1.07 (0.78–1.46) | 1.14 (0.81–1.61) | .33 |

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; HR, hazard ratio.

Levels of social integration are indicated in approximate tertiles (for a description of the measure for social integration, see Social integration [social network size] and social ties).

P values were used from continuous measures of social integration.

Model 1 was a minimally adjusted model adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), time between social assessment and diagnosis (continuous), study (clinical trial, observational study), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white [reference category], African-American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, other), and stage and grade (local [reference category], regional, distant and well differentiated/moderately differentiated, distant and nondifferentiated/anaplastic).

Model 2, which included possible confounding variables, was adjusted for the covariates in model 1 and additionally for site (rectal, colon [reference category]), education (<high school, high school, some college, college degree or greater [reference category]), income (<$20,000, $20,000 to <$50,000, ≥$50,000 [reference category]), family history of colorectal cancer (yes, no [reference category]), and comorbidity (yes, no [reference category]).

Model 3, which considered mediation by depressive symptoms and treatment and lifestyle factors, was adjusted for the covariates in model 2 and was also adjusted for surgery (yes, no [reference category]), chemotherapy (yes, no [reference category]), radiation (yes, no [reference category]), colorectal cancer screening (yes, no [reference category]), depressive symptomatology (continuous), aspirin or ibuprofen use (yes, no [reference category]), use of hormone therapy (yes, no [reference category]), alcohol intake (none [reference category], >0 to <1.7, 1.7 to <15, ≥15 g/day), smoking (never [reference category], past, current), physical activity (0 to <10 [reference category], 10 to <20, ≥20+ metabolic equivalents per week), and body mass index (<18.5, 18.5–25 [reference category]), 25-<30, ≥30 kg/m2).

Stratified Analyses

We noted little evidence of effect modification by education, family history of CRC, or caregiving. Although there was some evidence for effect modification by age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity, smoking, comorbidity, stage, and social strain, inconsistencies in findings for each social variable and type of outcome, as well as the small size of particular strata, made these differences difficult to interpret (data not shown). However, living alone appeared to be related more strongly to overall (P for interaction = .02) and CRC-specific (P for interaction = .03) mortality in patients with rectal cancer (Table 4). SN size also appeared to be more strongly related to outcomes in those with rectal cancer (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Relative Hazards of Mortality Among Women In the Women’s Health Initiative Diagnosed With Colorectal Cancer, by Cancer Sitea

| Characteristicb | HR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Colon Cancer | Rectal Cancer | |

| No. of women | 1168 | 183 |

| Overall mortality, no. | 445 | 68 |

| Level of social integration | ||

| Socially integrated | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderately integrated | 1.25 (0.96–1.63) | 1.82 (0.82–4.06) |

| Socially isolated | 1.32 (1.00–1.74) | 2.61 (1.15–5.92) |

| P for trend | .05 | .006 |

| P for interaction | .29 | |

| Living situation | ||

| Lives with someone | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Lives alone | 0.98 (0.79–1.22) | 1.81 (1.01–3.25) |

| P-value | .87 | .05 |

| P for interaction | .02 | |

| CRC-specific mortality, no. | 273 | 41 |

| Level of social integration | ||

| Socially integrated | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderately integrated | 1.25 (0.89–1.75) | 2.28 (0.83–6.26) |

| Socially isolated | 1.28 (0.89–1.84) | 3.43 (1.17–10.0) |

| P for trend | .22 | .05 |

| P for interaction | .65 | |

| Living situation | ||

| Lives with someone | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Lives alone | 0.93 (0.70–1.24) | 1.76 (0.77–4.01) |

| P for trend | .61 | .18 |

| P for interaction | .03 | |

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; HR, hazard ratio.

No difference was observed in the association between social support and outcomes by cancer site.

Models were adjusted for age at diagnosis (continuous), time between social assessment and diagnosis (continuous), study (clinical trial, observational study), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white [reference category], African-American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, other), and stage and grade (local [reference category], regional, distant and well differentiated/moderately differentiated, distant and nondifferentiated/anaplastic), site (rectal, colon [reference category]), education (<high school, high school, some college, college degree or greater [reference category]), income (<$20,000, $20,000 to <$50,000, ≥$50,000 [reference category]), family history of colorectal cancer (yes, no [reference category]), and comorbidity (yes, no [reference category]).

DISCUSSION

In this large study of postmenopausal women from the WHI who were diagnosed with CRC, those with low social support had higher rates of disease-specific and overall mortality than those with high levels of social support. Associations were independent of demographic factors, socioeconomic status, disease severity, depressive symptomatology, and lifestyle/behavioral factors. In main-effects analyses, SN size was associated with overall, but not CRC, mortality, and living alone did not predict either overall or CRC mortality. Social isolation and living alone appeared to be more strongly related to overall and CRC-specific mortality in patients with rectal cancer versus colon cancer. Our findings provide evidence that women with high levels of social support have longer CRC survival than women with low levels of social support. To our knowledge, this is the largest prospective study to date examining associations of social support, SNs, living situation, and CRC survival.

Limited work has evaluated social support, social ties, and CRC survival, although a growing number of studies suggest the importance of these factors in predicting CRC mortality. Being married has been associated with better survival in patients with CRC.11–15 In 896 women with CRC (mean age at diagnosis, 70 years) from the NHS, a large, longitudinal observational study, Sarma and colleagues10 found that those who were socially integrated before diagnosis had lower rates of all-cause mortality (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.46–0.92) and CRC-specific mortality (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.38–1.06) compared with women who were socially isolated. Social integration was assessed before CRC diagnosis using the Berkman-Syme SN index. By contrast, social support, assessed as the presence of a confidant, was unrelated to CRC survival. In 2835 women with breast cancer from the NHS, Kroenke et al reported parallel findings.3 Specifically, women who were socially isolated had higher overall mortality (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.04–2.65) and breast cancer-specific mortality (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.11–4.12) compared with those who were socially integrated, whereas social support, also assessed as the presence of a confidant, was unrelated to breast cancer survival. Kroenke and colleagues replicated findings for SN size and overall and breast cancer mortality in 9267 patients from the After Breast Cancer Pooling Project30 but did not examine social support and outcomes. Ell and colleagues also found no association of emotional support and CRC and lung cancer (combined) survival, but their study included only 76 patients with CRC.

The apparent relevance of structural or functional social supports to CRC survival and thus differences in study findings30 appear to be caused by differences in study measures, characteristics of study populations, type of cancer, cancer site, and outcome. Given the use of a well established, validated measure of social support, our findings are more likely than prior studies to provide an accurate estimate of associations. In our study, levels of social support, particularly tangible, emotional, and informational support, and positive interaction, were important predictors of CRC outcomes. By contrast, the presence of an emotional confidant, which was used in the NHS, is not a well established or validated measure of objective or perceived social support.

It is conceivable that we might have observed a stronger association of SN size and CRC-specific mortality if we had had data on close family and friends, which were the major predictors of cancer mortality in the NHS.3,10 SN size was nonetheless related to disease-specific mortality in patients with rectal cancer and in never-smokers in our study, suggesting that SNs may confer differential benefits, depending on cancer site or type of cancer, and/or that certain SNs are more salutary than others. Living alone, although not associated with mortality outcomes in main-effects analyses, was also more strongly related to outcomes in patients with rectal cancer, providing additional evidence that structural support measures matter for rectal cancer outcomes. Although healthy individuals, who may also be more likely to sustain extraspousal and extrafamilial SNs, may be more likely to live alone,31 living alone can augment mortality risk in individuals with limited social ties and mobility issues,32 and living alone has been associated with lower treatment intensity and poorer survival in patients with metastatic CRC.16 Thus the potential risk conferred by living alone may be situation-dependent, and the overall association could be a result of mixed effects. Further work is needed to replicate findings in a larger sample of patients, particularly in patients with rectal cancer given the relatively small number of those patients in the current study. Further work is also needed to explore whether associations differ in patients with distal or proximal colon cancers.

Strengths of the current study included the large sample size, prospectively collected data, the use of a well established measure of social support, consideration of competing risks, and an extensive set of covariates, enabling adjustment for disease severity, socioeconomic status, and several potential mediating factors. This study included social measures before diagnosis, enabling the assessment of social support unaffected by diagnosis. Study limitations included a lack of information on treatment for one-third of study participants, a lack of data on patient stomas, and limited numbers of patients with rectal cancer or comorbidities. A potential concern is the inclusion of those who had missing values for covariates, especially for treatment data. However, when we restricted our analyses to patients without missing data, associations were qualitatively similar (data not shown). Future studies should include greater representation of women from racial/ethnic minority groups and women of lower socioeconomic status.

Further research is also needed to elucidate explanatory mechanisms, given that adjustment for potential mediators did not explain associations. Social support may improve outcomes in other ways, such as through beneficial informal caregiving or physiologic intermediates like inflammatory biomarkers,33 factors we were unable to evaluate here.

In summary, among postmenopausal women with CRC, those with low social support had higher rates of overall and disease-specific mortality. Larger SNs and living with someone may confer a mortality benefit in patients with rectal cancer. Social support is important to prognosis in women with CRC, and clinicians should collect information on social support in these patients, to link patients to resources and to consider whether clinical care might be modified to accommodate social support needs.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING SUPPORT

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (grant K07 CA187403; principal investigator, Candyce H. Kroenke). The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Life and Longevity After Cancer (LILAC) study is funded by National Cancer Institute (grant UM1 CA173642; multiple principle investigator Garnet L. Anderson, Bette J. Caan, and Electra D. Paskett), and the WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201600018C, HHSN268201600001C, HHSN268201600002C, HHSN268201600003C, and HHSN268201600004C.

Footnotes

Women’s Health Initiative investigators include: Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller (Program Office; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland); Garnet Anderson, Ross Prentice, Andrea LaCroix, and Charles Kooperberg (Clinical Coordinating Center; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington); Investigators and Academic Centers: JoAnn E. Manson (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts), Barbara V. Howard (MedStar Health Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC), Marcia L. Stefanick; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, California), Rebecca Jackson (The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio), Cynthia A. Thomson (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, Arizona). Jean Wactawski-Wende (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York), Marian Limacher (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, Florida), Jennifer Robinson (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, Iowa), Lewis Kuller (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), Sally Shumaker (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina), and Robert Brunner (University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada).

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Electra D. Paskett reports grants from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation during the conduct of the study, grants from Merck Foundation outside the submitted, and stock ownership in Pfizer. The remaining authors made no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berkman LF, Glass T. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health In: Krieger N, Berkman LF, Kawachi I, eds. Social Epidemiology. Oxford University Press; 2000:137–173. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kroenke CH. A conceptual model of social networks and mechanisms of cancer mortality, and potential strategies to improve survival. Transl Behav Med 2018;8:629–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kroenke CH, Kubzansky LD, Schernhammer ES, Holmes MD, Kawachi I. Social networks, social support, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:1105–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kroenke CH, Quesenberry C, Kwan ML, Sweeney C, Castillo A, Caan BJ. Social networks, social support, and burden in relationships, and mortality after breast cancer diagnosis in the Life After Breast Cancer Epidemiology (LACE) study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013;137:261–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2011;75:122–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beasley JM, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Social networks and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Cancer Surviv 2010;4:372–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds P, Boyd PT, Blacklow RS, et al. The relationship between social ties and survival among black and white breast cancer patients. National Cancer Institute Black/White Cancer Survival Study Group. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1994;3:253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waxler-Morrison N, Hislop TG, Mears B, Kan L. Effects of social relationships on survival for women with breast cancer: a prospective study. Soc Sci Med 1991;33:177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ell K, Nishimoto R, Mediansky L, Mantell J, Hamovitch M. Social relations, social support and survival among patients with cancer. J Psychosom Res 1992;36:531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarma EA, Kawachi I, Poole EM, et al. Social integration and survival after diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2018;124:833–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Wilson SE, Stewart DB, Hollenbeak CS. Marital status and colon cancer outcomes in US Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results registries: does marriage affect cancer survival by gender and stage? Cancer Epidemiol 2011;35:417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3869–3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villingshoj M, Ross L, Thomsen BL, Johansen C. Does marital status and altered contact with the social network predict colorectal cancer survival? Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:3022–3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansen C, Schou G, Soll-Johanning H, Mellemgaard A, Lynge E. Influence of marital status on survival from colon and rectal cancer in Denmark. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:985–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kato I, Tominaga S, Ikari A. The role of socioeconomic factors in the survival of patients with gastrointestinal cancers. Jpn J Clin Oncol 1992;22:270–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavalli-Bjorkman N, Qvortrup C, Sebjornsen S, et al. Lower treatment intensity and poorer survival in metastatic colorectal cancer patients who live alone. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:189–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haviland J, Sodergren S, Calman L, et al. Social support following diagnosis and treatment for colorectal cancer and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the UK ColoREctal Wellbeing (CREW) cohort study. Psychooncology. 2017;26:2276–2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthews KA, Shumaker SA, Bowen DJ, et al. Women’s Health Initiative. Why now? What is it? What’s new? Am Psychol 1997;52:101–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Design of the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. The Women’s Health Initiative Study Group. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:61–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hays J, Hunt JR, Hubbell FA, et al. The Women’s Health Initiative recruitment methods and results. Ann Epidemiol 2003;13(9 suppl): S18–S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paskett ED, Caan BJ, Johnson L, et al. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Life and Longevity After Cancer (LILAC) study: description and baseline characteristics of participants. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2018;27:125–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curb JD, McTiernan A, Heckbert SR, et al. Outcomes ascertainment and adjudication methods in the Women’s Health Initiative. Ann Epidemiol 2003;13(9 suppl):S122–S128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 1991;32:705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardy SE, Concato J, Gill TM. Resilience of community-dwelling older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gold R, Michael YL, Whitlock EP, et al. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and lifetime morbidity burden in the Women’s Health Initiative: a cross-sectional analysis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15:1161–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, et al. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43:1575–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc B 1972;34: 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cupples LA, D’Agostino RB, Anderson K, Kannel WB. Comparison of baseline and repeated measure covariate techniques in the Framingham Heart Study. Stat Med 1988;7:205–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kroenke CH, Michael YL, Poole EM, et al. Postdiagnosis social networks and breast cancer mortality in the After Breast Cancer Pooling Project. Cancer. 2017;123:1228–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weissman JD, Russell D. Relationships between living arrangements and health status among older adults in the United States, 2009–2014: findings from the National Health Interview Survey. J Appl Gerontol 2018;37:7–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabue Teguo M, Simo-Tabue N, Stoykova R, et al. Feelings of loneliness and living alone as predictors of mortality in the elderly: the PAQUID study. Psychosom Med 2016;78:904–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Busch EL, Whitsel EA, Kroenke CH, Yang YC. Social relationships, inflammation markers, and breast cancer incidence in the Women’s Health Initiative. Breast. 2018;39:63–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.