Abstract

Background

Alcohol is often consumed with tobacco, and dependence to alcohol and tobacco are highly comorbid. In addition, there are differences in the prevalence of nicotine- and alcohol-abuse between the sexes. Nicotine produces enhancing effects on the value of other reinforcers, which may extend to alcohol.

Methods

Male and female Wistar rats were trained to self-administer 15% ethanol solution in 30-minute sessions. Once ethanol self-administration was established, demand for ethanol was evaluated using an exponential reinforcer demand method, in which the response cost per reinforcer delivery was systematically increased over blocks of several sessions. Within each cost condition, rats were preinjected with nicotine (0.05, 0.1, 0.2, or 0.4 mg/kg base, SC) or saline 5 minutes before self-administration sessions. The effects of nicotine dose and biological sex were evaluated using the estimates generated by the reinforcer demand model.

Results

Under saline conditions, males showed greater sensitivity to ethanol reinforcement than females. Nicotine enhanced the reinforcement value of alcohol and this varied with sex. In both sexes, 0.4 mg/kg nicotine decreased intensity of ethanol demand. However, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.2 mg/kg nicotine decreased elasticity of ethanol demand in females, but not in males.

Conclusions

Nicotine enhances ethanol reinforcement, which may partially drive comorbidity between nicotine-abuse and alcohol-abuse. Males showed signs of greater ethanol reinforcement value than females under saline conditions, and nicotine attenuated this effect by increasing ethanol reinforcement value in the females. These findings highlight that a complete understanding of alcohol-abuse must include a thorough study of alcohol use in the context of other drug use, including nicotine.

Implications

Nicotine dose dependently enhances the alcohol reinforcement value in a manner that is clearly influenced by biological sex. Under saline baseline conditions, males show lower elasticity of demand for alcohol reinforcement than females, indicative of greater reinforcement value. However, nicotine attenuated this difference by enhancing alcohol reward in the females. Specifically, low-to-moderate doses (0.05–0.2 mg/kg) of nicotine decreased elasticity of alcohol demand in female rats, increasing the perseverance of their alcohol taking behavior. These data indicate that the well-documented reward-enhancing effects of nicotine on sensory reinforcement extend to alcohol reinforcement and that these vary with biological sex.

Introduction

Tobacco use is the single greatest contributor to the global burden of preventable death and disease.1 Cigarette smoking accounts for 480 000 premature deaths annually in the United States alone; and for every smoking-related death, an additional 20 persons daily experience from serious smoking-related illness, including heart disease and cancer.2 A growing body of research implicates the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine in the acquisition and maintenance of tobacco use. Indeed, research investigating the incentives that establish and maintain nicotine administration increasingly indicates that the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine may be a greater contributor than the mild, primary reinforcing effects of nicotine alone.3 Although interest in the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine has grown in the recent decade, there remains much to be understood about the behavioral and neuropharmacological mechanisms of this enhancement effect.

Sex differences related to smoking and nicotine reward are numerous and well documented. The US Surgeon General published a 675-page report in 2001, entitled Women and Smoking, that highlights a massive body of research on the prevalence, risk factors, and health consequences of smoking among women and girls; a body of research that has only grown in the past 17 years.4 Despite the information now available documenting sex differences in smoking, we are a long way off from fully understanding the reasons behind those differences. Most research on sex differences in smoking has focused on differential sensitivity to the primary reinforcing effects of nicotine alone. Interestingly, much of that research has revealed that females may be less sensitive than males to the pharmacodynamic effects of nicotine related to reinforcement and reward.5 Although evidence suggests that females may be less sensitive than males to the primary rewarding effects of nicotine, increasing evidence suggests that females are more sensitive to the sensory elements of smoking. For instance, Perkins et al.6 found that the presentation of a lit cigarette cue shifted preference toward smoking more in females than males in a procedure arranging concurrent availability of cigarette puffs and monetary reward on competing response alternatives. Chaudhri et al.7 found that female rats will earn more visual stimulus (VS) presentations than males on low fixed-ratio (FR) schedules of reinforcement, which corresponded to higher rates of lever-pressing for VS coupled with response contingent nicotine infusions on an FR 5 schedule of reinforcement. In our laboratory, we recently found that nicotine and the smoking cessation aid bupropion (Zyban) enhanced VS-maintained operant responding to a greater degree in females than in males on a wide range of ratio schedules of reinforcement.8,9 Together, these data suggest differences in the relative involvement of the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine and the sensory elements of smoking between the sexes.

The reward-enhancing effects of nicotine have important implications in the context of polydrug abuse and dependence. Particularly noteworthy is the close association between nicotine dependence and alcohol dependence. Although overall smoking rates have generally decreased in the United States over the past few decades, smoking rates among individuals with alcohol-use disorder have remained high.10,11 Between 50% and 80% of alcohol-dependent persons in the United States smoke regularly, and alcoholic individuals who smoke demonstrate greater alcohol consumption than nonsmoking alcoholic individuals. Furthermore, among Americans seeking treatment for alcohol dependence, smoking-related mortality is 1.5 times higher than alcohol-related mortality.11,12 Given the common comorbidity between smoking and alcohol dependence, research elucidating the behavioral and neuropharmacological mechanisms of comorbid nicotine- and alcohol-abuse should be of high priority and may inform treatments and public policies that save millions of lives.

There is a growing body of research investigating the interaction between nicotine and alcohol reinforcement in human and nonhuman animals. Of critical interest is the question of whether nicotine or alcohol administration alters the reinforcing capacity of the other. In general, nicotine increases alcohol-maintained operant responding,13–15 motivation to respond for alcohol reward,16,17 and triggers alcohol reinstatement.18 In addition, Barrett et al.19 found that 1.2 mg/kg nicotine increased alcohol consumption and motivation to work for alcohol using human participants exposed to a progressive ratio alcohol self-administration task. Acheson et al.20 showed that nicotine increased alcohol consumption in men, but decreased consumption in women, suggesting important interactions with biological sex or variables conflated with sex. Studies examining the effects of nicotine on the subjective effects of alcohol reveal that nicotine pretreatment reduces the sedative effects of alcohol and increases feelings of alcohol intoxication and desire to drink.21 These studies strongly suggest that nicotine enhances alcohol reinforcement in a manner similar to its enhancement of other sensory or appetitive reinforcers, which effect may be a significant contributor to the comorbidity of nicotine and alcohol dependence.

This study investigated whether the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine extend to alcohol self-administration. In our previous work, we demonstrated that 0.4 mg/kg nicotine administered subcutaneously will enhance the reinforcement value of a mildly reinforcing VS as assessed via a behavioral-economic, reinforcer-demand model.8,9,22 Among the findings of these previous studies was that females and males differed in sensitivity to the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine on VS reinforcement.8,9 Inasmuch as previous work has shown differential sensitivity between the sexes in the effects of nicotine on alcohol reward,20 this study examined whether sex differences would be apparent in the reinforcing effects of alcohol, and the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine on alcohol reinforcement.

Methods

Animals

Twenty (10 per sex) experimentally naive male and female Wistar rats (Harlan Indianapolis, IN), 9 weeks of age upon arrival, were individually housed in clear polycarbonate tubs lined with TEK-Fresh cellulose bedding in a temperature- and humidity-controlled colony. The rats were given 2 days to acclimate to the colony followed by three additional days of handling before initiation of training. Water was continuously available in the home-cage and the rats were given 12 (females) or 15 g (males) of laboratory chow daily, unless otherwise specified. Sessions were conducted during the light phase of a 12:12 hour light to dark cycle. Experimental protocols were approved by the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Apparatus

For this study, we used 10 conditioning chambers (ENV-008CT; Med Associates Inc, St. Albans, VT; measuring 30.5 × 24.1 × 21.0 cm, L × W × H) enclosed in light- and sound-attenuating cubicles fitted with an exhaust fan. Sidewalls were aluminum; the ceiling and front and back walls were clear polycarbonate. One sidewall featured a dipper receptacle, occupying a 5.2 × 5.2 × 3.8 cm (L × W × D) recessed space, into which a dipper arm provided 0.1 mL of solution when raised. This receptacle was also fitted with an infrared emitter–detector unit for recording instances of head entry to the dipper receptacle. Retractable response levers were featured on either side of the dipper receptacle, approximately 5 cm above the rod floor. Two 28-V DC (100 mA) lamps were located above the conditioning chamber, but within the sound-attenuating cubicle, hereafter termed the houselight. An infrared emitter and detector unit, positioned 4 cm above the floor, bisected the chamber 14.5 cm from the sidewall featuring the dipper receptacle and functioned to monitor general locomotor activity.

Drugs

(−)-Nicotine hydrogen tartrate (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) was dissolved in 0.9% saline and administered subcutaneously at an injection-to-placement interval of 5 minutes. All doses (vehicle, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 mg/kg base) were pH adjusted to 7.0 ± 0.2 with a NaOH solution and injected at a volume of 1 mL/kg. Ethyl alcohol (95%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was diluted (vol/vol) with purified water (reverse osmosis) and mixed with granulated sucrose to obtain desired ethanol and sucrose concentrations throughout training and subsequent ethanol self-administration.

Lever Training via Sucrose Fading

Over four sessions, rats were trained to lever-press using an “autoshaping” procedure with 10% sucrose solution.23 Each session began with random insertion of one of the two response levers. After a lapse of 15 seconds or a lever-press, the response lever was immediately retracted, and the dipper arm was raised for 4 seconds. Following a variable time-out length (average 60 seconds, range 30–90 seconds), the opposite lever was inserted into the chamber, initiating a new trial as just described. The lever inserted on odd-numbered trials was always randomly determined, and the opposite lever always followed on even-numbered trials. Thus, over a 60-trial session, each lever was inserted 30 times but never presented more than two times in succession. Each session was conducted in continuous houselight illumination and no other stimuli were presented.

Rats were subsequently trained to self-administer ethanol solution using a sucrose-fading procedure in daily 30-minute sessions. Active and inactive lever assignments were pseudorandomly determined and counterbalanced within groups. Brief presentations of liquid reinforcement (4 seconds) were delivered on FR 1 schedule (one response per reinforcer) for responding on the active lever; responses on the inactive lever were recorded but had no programmed consequence. Reinforcer consumption was determined by the number of dipper presentations during which at least one head-entry into the dipper receptacle. Over the course of the sucrose-fading phase, the solution available contingent upon lever-pressing was adjusted by first increasing the ethanol concentration, and then by decreasing the sucrose concentration. Training began with 10% sucrose solution, of which the ethanol concentration was increased every 2 days per the following sequence: 2%, 5%, 10%, 15%. To encourage high levels of sustained intake, rats were maintained on the 10% sucrose and 15% ethanol solution for 20 days. Subsequently, the sucrose concentration was decreased every 3 days per the following sequence: 10%, 5%, 2%, 0%. Responding was then maintained on the 15% ethanol (0% sucrose) solution for 5 days before proceeding with the demand assessment phase.

Demand Assessment

Demand assessment occurred across 110 sessions, over which the FR-scheduled response requirement for obtaining ethanol presentations was increased every 10 sessions per the following sequence: 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120. Within a 10-session block, each rat was injected with either saline or 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, or 0.4 mg/kg nicotine (SC, 5-minute injection-to-placement interval), such that each dose condition was tested twice on each FR schedule for each rat. Testing order for each dose determination was randomly generated and then counterbalanced across rats within each sex. Rat weights were taken daily before injection and placement in the test chambers. For purposes of applying the reinforcer demand model, reinforcer consumption was averaged over the two determinations of each nicotine dose at each FR schedule. In addition, the weight of each rat was averaged over each 10-session FR block and unit cost was calculated as the programmed response requirement divided per one dipper per kilogram bodyweight.

Once rats had experienced all test conditions, the data were analyzed and demand curves were generated by applying the model developed by Hursh and Silberberg24:

| (1) |

In this model, Q reflects units of reinforcer consumption, Q0 is predicted consumption in the absence of the constraint of cost (ie, the ordinate intercept), k is a constant reflecting the range of the demand function in log units of consumption, e is the base of the natural logarithm, C is the response cost to obtain reinforcement, and α represents the rate of change in decline of consumption in standardized price (Q0* C). The values of Q0 and α are permitted to vary to maximize the fit of the demand model and may be conceptualized to represent basal intensity of demand (Q0) and elasticity of demand (α).24,25 That is, Q0 represents consumption where the only constraint is satiation and α reflects the limiting effects of both satiation and price on consumption by representing the rate at which consumption shifts toward being primarily constrained by price rather than by satiation.24–27 Importantly, the essential value (EV) of a reinforcer is inversely related to sensitivity to price (α) and can be calculated from the demand model as:

| (2) |

where EV is conceptualized as the strength of a reinforcer to maintain behavior independent of scalar manipulations of reinforcer magnitude and accounting for individual sensitivity to response cost.24,25

Dependent Measures

The primary dependent measures used throughout the study were total locomotor beam breaks, total dipper presentations, and the number of reinforcers accessed. Alcohol consumption is presented as the number of reinforcers given during which at least one head-entry to the dipper receptacle was made, normalized with respect to body weight. Although grams per kilogram ethanol consumption could be estimated from the number of reinforcers accessed, it is unlikely that each rat consumed the entire dipper volume during each presentation. Therefore, we present alcohol consumption as reinforcers accessed in this study as an agnostic measure of reinforcer consumption. For demand analyses, reinforcer consumption and unit response cost were both normalized with respect to bodyweight.

Blood-Alcohol Quantification

In order to demonstrate that rats in this study consumed biologically significant levels of alcohol, we conducted a follow-up experiment wherein 20 separate rats (10 per sex) were trained to self-administer 15% ethanol using the same procedures described earlier. These rats had been previously exposed to nicotine and norharman 2 months prior. Once stable responding maintained by 15% ethanol had been sustained for at least 2 weeks, we collected blood samples following a 30-minute self-administration session (FR 1) to determine blood-alcohol levels. Blood was obtained by decapitation and collection in a 1.5-mL centrifuge tube doped with 30 U of heparin to prevent coagulation. The tubes were centrifuged at 2000g for 2 minutes to separate cells from the plasma. The plasma was aspirated and placed in a clean tube and kept on ice for duration of the collection and assay periods. To quantify the ethanol in blood, the plasma was diluted 100-fold with assay buffer from a standard kit (MAK076-1kt; Sigma-Aldrich) and mixed with the ethanol probe and enzyme mix and allowed to incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes in a 96-well format. The colorimetric reaction was then quantified by a SpectraMax M2 plate reader (Molecular Dynamics) at 570 nm and the amount of ethanol (C) was calculated with the following equation C = Sa/Sv in which Sa is nanomole of ethanol in the sample as compared to a standard curve and Sv is the sample volume.

Statistical Analyses

The effects of nicotine dose and FR schedule on active lever-pressing and locomotor activity over the sessions of the demand assessment phase were analyzed using mixed-factorial analysis of variance with sex as a between-subjects factor and injection and FR schedule as within-subject factors. Estimates of the ordinate intercept (Q0) and essential value of ethanol (EV) were determined via fits of the reinforcer demand model to the consumption data of individual rats. Analyses of Q0 and EV were conducted using mixed-effects analysis of variance with sex and injection as fixed effects and allowing the intercept to vary by subjects, using Kenward–Roger degrees of freedom.28 Because the distributions of residuals for EV approached log-normality (assessed via the Shapiro–Wilks test and visually via quantile-quantile plots), values of EV were log-transformed for all analyses and presentation in Figure 5. All pairwise comparisons corrected family-wise error rates using the Tukey’s honestly significant difference method with significance set at adjusted p values <.05.29 Measures of blood-alcohol content (BAC) were correlated with reinforcer consumption (dippers accessed per kilogram bodyweight) using Pearson correlations. Fitting of the reinforcer demand model was performed using Prism v7.01 (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA). All other analyses were performed using the lme4, emmeans, and pbkrtest packages for R version 3.5.1.30–33

Results

All rats maintained reliable self-administration of 15% ethanol solution following the sucrose-fading procedure. The mean number of reinforcers accessed (±1 SEM) between sexes over the five sessions of FR 1 maintenance preceding the initiation of formal demand assessment was 36.6 (±11.2 SEM) for females and 63.6 (±13.9 SEM) for males. These numbers represent an immediate 27.5% decrease in reinforcers accessed relative to the last solution containing any sucrose during fading. Furthermore, analysis of the effects of sex and session over indicated a significant effect of sex [F(1,18) = 15.4; p < .001], but not of session and no interaction with session [Fs(4,72) ≤ 1.71; ps ≥ .157]. Together, these demonstrate that 15% ethanol self-administration was stable over the 5-day period before initiation of formal demand assessment.

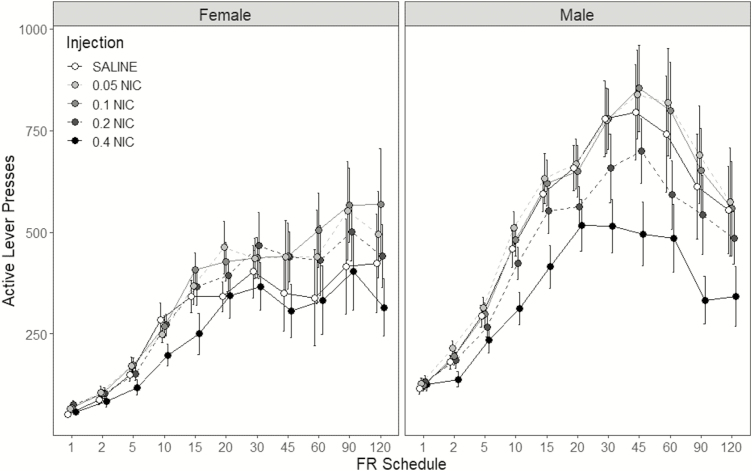

Active lever-pressing between sexes, nicotine dose conditions, and the range of FR schedules tested throughout the demand assessment phase is portrayed in Figure 1. Active lever-pressing progressively increased, and subsequently plateaued or decreased with increases in the FR schedule response requirement across all conditions. Analyses of active lever-pressing revealed significant interactions of sex × injection [F(4,72) = 4.70; p = .002], and injection × FR schedule [F(40,720) = 2.57; p < .001]. The main effects of injection [F(4,72) = 22.3; p < .001] and FR schedule were also significant [F(10,180) = 20.1; p < .001]. The sex × injection × FR schedule interaction was not significant [F(40,720) = 1.15; p = .250]. Investigation of the injection × FR schedule interaction discovered significant decreases in active lever-pressing wrought by 0.4 mg/kg nicotine relative to saline at FRs 10, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 (ps ≤ .011). At FR 60, administration of 0.1 mg/kg nicotine increased active lever-pressing relative to saline, 0.2 and 0.4 mg/kg nicotine (ps ≤ .038). Further analysis of the injection × sex interaction revealed significant decreases in active lever-pressing by 0.4 mg/kg nicotine relative to saline in males (p < .001) but not in females (p = .593). However, 0.4 mg/kg nicotine decreased active lever-pressing relative to every other nicotine dose in both sexes (ps ≤ .026). In males, 0.2 mg/kg nicotine also decreased active lever-pressing relative to 0.05 and 0.1 mg/kg nicotine (ps ≤ .016), but not relative to saline (p = .121). Active lever-pressing has higher in males than in females at the saline condition (p = .046), but not at any other condition of nicotine dose (ps ≥ .066).

Figure 1.

Mean active lever-presses (±1 SEM) as a function of fixed-ratio (FR) schedule in the female (left panel) and male (right panel) rats, between conditions of nicotine dose. Nicotine dose conditions are signified by the fill-color and dash-pattern of connecting lines. Each dose condition was tested twice under each FR schedule.

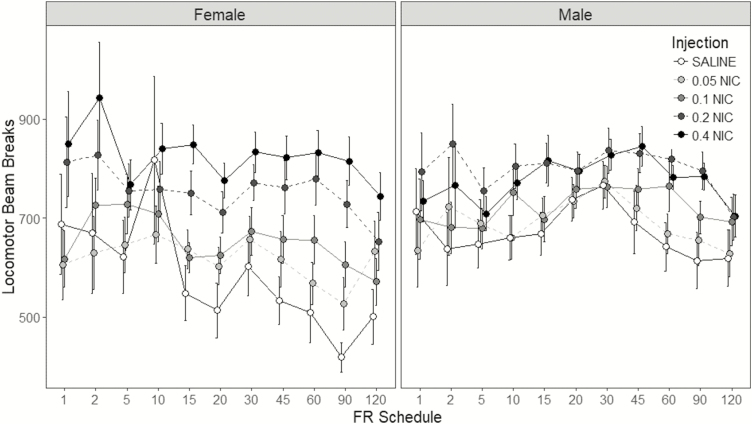

For analysis of locomotor activity (Figure 2), there was a significant effect of injection [F(4,72) = 29.2; p < .001], as well as significant interactions of sex × injection [F(4,72) = 3.82; p = .007] and injection × FR schedule [F(40,720) = 1.61; p = .011]. The sex × injection × FR schedule interaction was not significant (F < 1). Closer examination of the sex × injection interaction revealed significant increases in locomotor activity by 0.2 and 0.4 mg/kg nicotine relative to saline in both sexes (ps ≤ .004). Activity in the 0.2 and 0.4 mg/kg nicotine conditions was significantly higher than 0.05 and 0.1 mg/kg nicotine in both sexes (ps ≤ .005). In males, 0.2 and 0.4 mg/kg nicotine increased locomotor activity relative to 0.05 mg/kg nicotine (ps ≤ .026), whereas neither dose differed from 0.1 mg/kg nicotine (ps ≥ .056). Investigation of the injection × FR schedule interaction discovered increases in locomotor activity by 0.2 mg/kg nicotine relative to saline on all schedules but FR 1 and 10 (ps ≤ .030), relative to 0.05 mg/kg nicotine on FRs 1, 2, 10, 45, 60, and 90 (ps ≤ .031), and relative to 0.1 mg/kg nicotine on FRs 1, 2, and 15 (ps ≤ .021). Likewise, 0.4 mg/kg nicotine increased locomotor activity relative to saline on all FRs except 1, 5, and 10 (ps ≤ .003), relative to 0.05 mg/kg nicotine on all FRs except 5 and 120 (ps ≤ .036), and relative to 0.1 mg/kg nicotine on FRs 1, 2, 15, 30, 45, and 90 (ps ≤ .043).

Figure 2.

Mean locomotor activity counts (±1 SEM) as a function of fixed-ratio (FR) schedule, in the female (left panel) and male (right panel) rats, between conditions of nicotine dose. Nicotine dose conditions are signified by the fill-color and dash-pattern of connecting lines. Each dose condition was tested twice under each FR schedule.

Reinforcer Demand

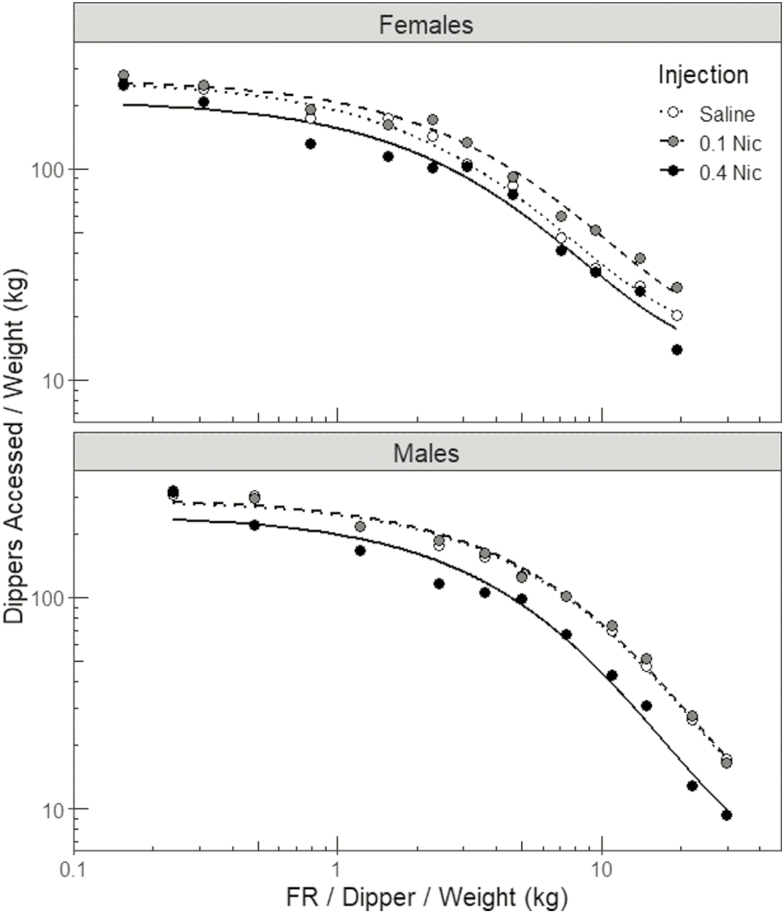

For representation purposes, fits of the reinforcer demand model to group-mean reinforcer consumption data are presented in Figure 3. For clarity in presentation, only data from the saline and 0.1 and 0.4 mg/kg nicotine conditions are presented (both 0.05 and 0.2 mg/kg are well characterized by the 0.1 mg/kg data for each sex). For analyses, the reinforcer demand model was fit to the consumption data separately for each rat at each nicotine dose condition to obtain estimates of Q0 and EV for each individual rat at each nicotine dose. To ensure comparability of the demand estimates between subjects and conditions, the value of k for fitting the model was constrained to be shared (k = 1.88) across all 100 fits of the demand model;24,25 the mean R2 across these fits was 0.905 (±0.009 SEM). Mean estimates (±1 SEM) of Q0, EV, and R2 across conditions of sex and injection are also presented in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Fits of the reinforcer demand model (lines) to the observed reinforcer consumption data (points) as fit to the group-averaged consumption data in the female (top panel) and male (bottom panel) rats. These curves are presented for representation purposes only, and for sake of clarity in presentation, curves for 0.05 and 0.2 mg/kg nicotine are not displayed (these are well characterized by 0.1 mg/kg in each sex). For actual analysis purposes, the reinforcer demand model was fit to the consumption data under each drug condition for each individual rat, yielding 100 separate fits of the demand model (mean R2 = 0.905). Unit cost represents the response requirement per one dipper per kilogram bodyweight. Note the logarithmic scales of the y- and x-axes.

Table 1.

Mean Fitting Parameters From the Reinforcer Demand Model (±1 SEM)

| Sex | Dose | Q 0 | log EV | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (n = 10) | Saline | 294 ± 20.5 | 1.43 ± 0.076 | 0.952 ± 0.008 |

| 0.05 Nic | 311 ± 19.1 | 1.45 ± 0.076 | 0.950 ± 0.013 | |

| 0.1 Nic | 294 ± 21.0 | 1.44 ± 0.070 | 0.952 ± 0.011 | |

| 0.2 Nic | 285 ± 23.3 | 1.36 ± 0.074 | 0.955 ± 0.010 | |

| 0.4 Nic | 234 ± 27.5 | 1.20 ± 0.098 | 0.886 ± 0.037 | |

| Females (n = 10) | Saline | 261 ± 29.2 | 1.09 ± 0.107 | 0.882 ± 0.029 |

| 0.05 Nic | 261 ± 30.8 | 1.21 ± 0.094 | 0.881 ± 0.018 | |

| 0.1 Nic | 247 ± 26.0 | 1.25 ± 0.086 | 0.904 ± 0.021 | |

| 0.2 Nic | 236 ± 33.6 | 1.21 ± 0.086 | 0.893 ± 0.020 | |

| 0.4 Nic | 202 ± 34.9 | 0.980 ± 0.132 | 0.798 ± 0.060 |

EV = essential value.

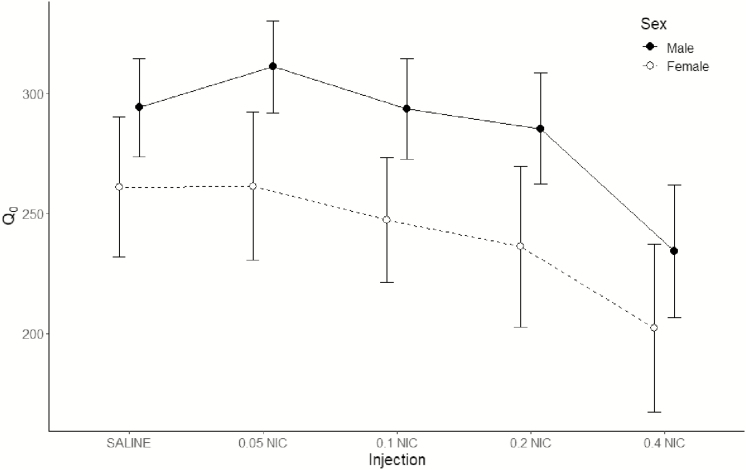

Mixed-factorial analysis of variance on estimates of Q0 (Figure 4) revealed a significant main effect of injection [F(4,72) = 11.4; p < .001], but not of sex [F(1,18) = 1.39; p = .253], and no sex × injection interaction (F < 1). Further investigation of the effect of injection on Q0 discovered significant decreases Q0 by 0.4 mg/kg nicotine relative to saline, and every other nicotine dose (ps ≤ .003). No other effects of nicotine dose were significant (ps ≥ .157).

Figure 4.

Mean estimates (±1 SEM) of the ordinate intercept (Q0) generated by fits of the reinforcer demand model to the consumption data of individual rats, displayed as a function of nicotine dose. Data from the males is displayed using closed circles and a solid line; data from the females is displayed using open circles and a dashed line. Points are offset for improved readability.

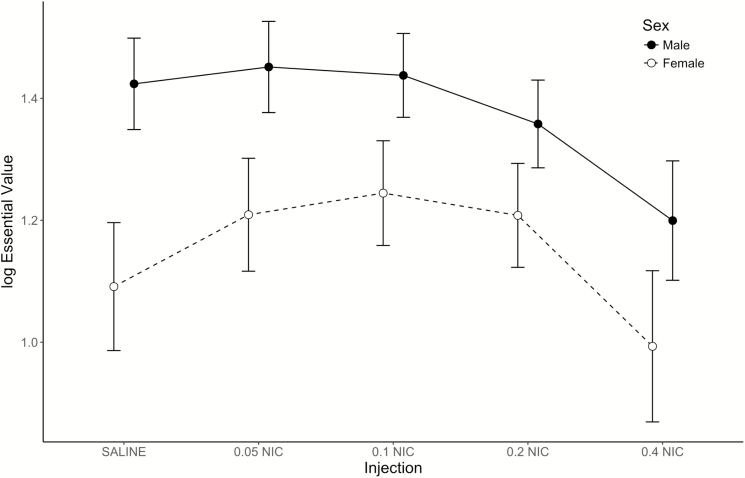

Analysis of EV (Figure 5) discovered a significant main effect of injection [F(4,72) = 24.5; p < .001], no main effect of sex [F(1,18) = 3.36; p = .084], and a significant sex × injection interaction [F(4,72) = 2.90; p = .028]. Closer examination of the sex × injection interaction found higher EV in males than females under the saline condition (p = .017), but no sex differences in EV when administered any dose of nicotine (ps ≥ .077). Administration of 0.05, 0.1, and 0.2 mg/kg nicotine increased EV of ethanol relative to saline in females (ps ≤ .038), but not in males (ps ≥ .463). Conversely, administration of 0.4 mg/kg nicotine decreased EV of ethanol relative to saline in males (p < .001), but not in females (p = .077). However, EV was lower in the 0.4 mg/kg nicotine condition relative to every other nicotine dose in both sexes (ps ≤ .003).

Figure 5.

Mean estimates (±1 SEM) of essential value (EV) generated by fits of the reinforcer demand model to the consumption data of individual rats, displayed as a function of nicotine dose. Data from the males are displayed using closed circles and a solid line; data from the females are displayed using open circles and a dashed line. Points are offset for improved readability.

Blood-Alcohol Quantification

Table 2 presents the mean reinforcers earned, reinforcers accessed, reinforcers accessed per kilogram bodyweight, estimated ethanol consumption (g/kg), and blood BAC for the 20 rats who were separately trained to self-administer ethanol for blood-alcohol verification purposes. Two-sample t test comparing reinforcers accessed per kilogram bodyweight between the sexes revealed no differences between males and females [t(18) = 1.90; p = .073]. Similar analysis of BAC also found no effect of sex [t(18) = 0.273; p = .788]. The Pearson correlation between reinforcers accessed per kilogram bodyweight and BAC was significantly positive (r = .720; t(18) = 4.40; p < .001).

Table 2.

Mean Reinforcer Consumption and Blood-Alcohol Consumption (±1 SEM)

| Sex | Dippers earned | Percent accessed | Reinforcers per kg | EtOH (g/kg) | BAC (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (n = 10) | 98.5 ± 8.90 | 86.3 ± 4.97 | 253 ± 22.0 | 2.99 ± 0.260 | 61.7 ± 1.97 |

| Females (n = 10) | 52.5 ± 6.84 | 89.7 ± 3.05 | 198 ± 19.3 | 2.33 ± 0.229 | 62.7 ± 3.42 |

BAC = blood-alcohol content; EtOH = ethanol.

Discussion

Nicotine dose-dependently enhanced ethanol consumption and ethanol reinforcement value in a manner that was clearly influenced by biological sex. That is, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.2 mg/kg nicotine each increased the EV of ethanol reinforcement in female rats but not in male rats. Conversely, 0.4 mg/kg nicotine decreased estimates of Q0 in both sexes, and no effects on Q0 were detected with any other dose. Together, these findings suggest that nicotine at lower doses (0.05, 0.1, and 0.2 mg/kg) produces an enhancement of ethanol reinforcement value in female rats, indicative of a decrease in elasticity of demand without altering the baseline intensity of demand for ethanol. At higher doses (0.4 mg/kg nicotine), nicotine may dampen ethanol reinforcement value by lowering the intensity of demand for ethanol and by increasing elasticity of demand. Importantly, these results indicate that the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine extend to ethanol reward, and these effects may play a larger role in driving comorbidity between nicotine-abuse and alcohol-abuse in females than in males.

These findings stand in contrast to a previous report by Acheson et al.20 who found that nicotine increased alcohol consumption in men and decreased consumption in women.20 However, there are several notable differences between their study and the present. Acheson et al. administered nicotine via transdermal patch to male and female light smokers, who were required to drink a single individualized alcoholic drink (0.2 g/kg) and then permitted to buy up to 8 optional drinks (0.1 g/kg each), one every 15 minutes. This enforced a hard ceiling on ethanol consumption at 1 g/kg over a 2-hour period. Doses for females were 10% lower than males to account for differences in body composition. Drinks were 16% ethanol diluted in orange juice, and the price of drinks was individually determined as the monetary value that resulted in indifference between the choice of a monetary reward and a standard drink (ie, can of beer, etc.).20 By contrast, participants in this study were drug-naive male and female rats given unconstrained access to unsweetened 15% ethanol solution over a 30-minute period, nicotine was administered via injection, and the price of drinks was systematically varied over a wide range. Given the great number of variables that differ between these two studies, it is difficult to determine which specifically may account for the discrepancy between these sets of findings. However, the list of differences between these studies do suggest some potential variables of interest for future research, such as economy type (open or closed; income constraint), drink composition (sweetened vs. unsweetened), or history of nicotine self-administration.

A notable finding of this study is that the reward-enhancing and locomotor-activating effects of nicotine did not operate in parallel for ethanol self-administration. That is, nicotine at 0.2 and 0.4 mg/kg increased locomotor activity relative to saline in both sexes, whereas lower doses had no effect on locomotor behavior. By contrast, lower doses of nicotine enhanced ethanol self-administration in a sex-specific manner, whereas 0.4 mg/kg nicotine reliably decreased ethanol consumption in both sexes. These findings suggest that the enhancement of ethanol consumption in females by 0.05, 0.1, and 0.2 mg/kg nicotine was not an artifact of locomotor activation by nicotine. Likewise, the decrease in ethanol consumption produced by 0.4 mg/kg nicotine was not caused by locomotor suppression at this dose. These findings corroborate previous work from our laboratory on the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine that demonstrate that the locomotor- and reward-altering effects of nicotine are concurrent but independent effects of nicotine on behavior.8,9,22,34

Reward-enhancement by nicotine has been demonstrated in both clinical and preclinical settings. Smokers will work harder for brief presentations of preferred music after smoking nicotine-containing cigarettes than after smoking denicotinized cigarettes or during abstinence.35 Interestingly, smokers will work equally hard for puffs of denicotinized and nicotine-containing cigarettes, but express a preference for, and report greater enjoyment of, nicotine-containing cigarettes.36,37 Preclinical work on nicotine self-administration has demonstrated that the primary reinforcing effects of nicotine are relatively weak and will not reliably maintain operant behavior without the inclusion of sensory cues concurrent with drug delivery, or other peculiarities in training or test conditions.38–40 In these experiments, nicotine self-administration behavior appears to be driven less by the rewarding effects of nicotine and more by the sensory cues whose value is amplified by the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine.

This study demonstrates the utility of reinforcer demand analyses in assessing the reinforcement value altering effects of drugs in the wider context of polydrug administration. Reinforcement value is a complex and multifaceted construct that may refer to many aspects of behavior including frequency, intensity, persistence, effort, and preference. The traditional measure of reinforcer value, or response strength, is the rate of response (or response totals) on the active manipulandum. However, there are often issues with relying upon this measure alone. For instance, response rate may vary with schedule of reinforcement maintaining the response. In studies like the present, higher levels of responding are commonly observed with higher ratio-based schedules. A consideration of response schedules that is often overlooked is the unit response cost of reinforcement, which may vary between individuals or groups despite maintenance on identical ratio-based schedules of reinforcement. In this study, males and females responded on the same FR schedules of reinforcement for presentations of identical volume ethanol reward (0.1 mL). However, because males and females differed considerably in respect to weight (as did individual males or females respective to other members of their own sex), the unit cost of ethanol presentation varied between these groups. A traditional assessment of reinforcement value as total responding maintained by the same FR schedules without accounting for differences in unit cost would have ignored the important influence that response cost exerts on behavior. Reinforcer demand analysis avoids this pitfall because the effects of cost on behavior are assessed on the individual level as cost per units of consumption. Furthermore, reinforcer demand analyses provide a richer characterization of reinforcement value by assessing behavior across a range of maintenance conditions and affording the potential to detect interactions with experimental parameters with variation in the maintenance schedule. Finally, the estimates of Q0 and EV that can be obtained by demand analyses provide two measures of reinforcement value that reflect differing dimensions of consumption behavior and the constraints on that behavior. For these reasons, reinforcer demand analysis is a superior method for quantifiably assessing alterations in reinforcement value to more traditional methods. We encourage their use in investigating interactions between drugs in the context of polydrug abuse when possible.

In this study, alcohol consumption is presented as the number of dippers delivered during which at least one head-entry was made to the dipper receptacle. Traditionally, ethanol consumption is expressed in units of grams ethanol per kilogram bodyweight, which measure could be estimated from the volume of the dipper cup, number of dippers accessed, concentration of ethanol solution, and body weight of each rat in this study. However, such an estimate would require the assumption that rats consumed the entire volume of ethanol during each accessed delivery, which seems unlikely. Moreover, estimates obtained by this approach seem unrealistically high in this study [2.81 g/kg (±0.965 SEM) for females; 3.44 g/kg (±0.810 SEM) for males]. Therefore, rather than present an estimate of gram per kg ethanol consumption that may be misleading, we present ethanol consumption more agnostically as the number of dippers accessed per kilogram bodyweight and acknowledge that the full volume of each dipper may not have been consumed. To verify that rats in this study were likely consuming significant levels of alcohol, we analyzed the BAC of 20 separate rats trained on an identical procedure. The BAC data from these rats are consistent with other studies of ethanol self-administration and support the conclusion that the rats in this study consumed biologically significant amounts of ethanol.41,42 Regardless of the exact measurement of ethanol consumed, the present data strongly demonstrate that 15% ethanol will maintain robust rates of operant behavior maintained on escalating FR schedules of reinforcement, and that nicotine alters the reinforcement value of ethanol reward.

This study adds to previous reports that demonstrate that nicotine enhances alcohol reinforcement and extends these findings by examining sex as a biological variable. Previous work has shown that nicotine pretreatment increases alcohol intake, enhances ethanol self-administration, increases persistence on progressive ratio schedules, and triggers ethanol reinstatement in animal models of drinking behavior.13–18 Similarly, nicotine also increases the subjective effects of drunkenness, desire to drink, head rush, and arousal from alcohol administration in human studies.21,43 These findings, in combination with the present work, suggest that the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine that are well documented with other appetitive rewards and with sensory reinforcers, extend to alcohol reinforcement and likely contribute to alcohol-abuse. However, a common limitation of a significant majority of these studies is inclusion of only males as participants.10 In those studies that have included both sexes, including this study, findings indicate that the effects of nicotine on alcohol reinforcement vary considerably between sexes. For example, Acheson et al.20 found that nicotine treatment increased alcohol self-administration in men, but decreased administration in women.20 In contrast, this study found that lower doses of nicotine enhanced ethanol reinforcement only in females and had suppressive effects on ethanol self-administration at the highest dose in both sexes. However, we have also found that 0.4 mg/kg nicotine decreased ethanol consumption in both sexes at lower unit costs and can enhance ethanol-maintained responding at higher costs in longer, 1-hour sessions (unpublished observation). The seeming discrepancy between these sets of findings highlight the need for additional, programmatic work that appropriately includes biological sex as a variable of research interest regarding the connection between nicotine- and alcohol-abuse.

Nicotine-abuse and alcohol-abuse, separately, represent two areas of critical research important for improving human health outcomes, as they account for the first and third leading causes of preventable death and disease in the United States, respectively.44 Understanding either of these forms of drug-abuse on their own, is already a difficult task, let alone their interaction. However, given the considerable behavioral and neuropharmacological overlaps between nicotine and alcohol reinforcement, and given their strong association and comorbidity, we contend that neither form of drug-abuse can truly be understood in the absence of the other. To that end, we encourage researchers in the field of addiction to continue their efforts to understanding these two phenomena by devoting particular attention to their intersection and interaction, neurobiologically and behaviorally.

Funding

The work reported in the present study was supported by funding through a grant of the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services (LB506 2015), entitled Nicotine Enhancement of Alcohol Seeking. Additional support was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA034389).

Acknowledgments

We thank David Kwan, Olivia Loh, and Stephanie Marsh for their assistance with conducting daily experimental sessions. We also thank Joyce Besheer, Wendy Huynh, David Kwan, Jake Derby, and Anthony Raimondi for their comments of an earlier version of this manuscript. The Med Associates programs used in this research, or a more recent version, are available upon request.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Neuroscience of Psychoactive Substance Use and Dependence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Palmatier MI, Liu X, Chaudhri N, Sved AF. The role of nicotine in smoking: A dual reinforcement model. In: Bevins RA, Caggiula AR, eds. The Motivational Impact of Nicotine and its Role in Tobacco Use. New York, NY: Springer Science and Business Media; 2009:91–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Women and Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perkins KA. Sex differences in nicotine reinforcement and reward: Influences on the persistence of tobacco smoking. In: Bevins RA, Caggiula AR, eds. The Motivational Impact of Nicotine and its Role in Tobacco Use. New York, NY: Springer Science and Business Media; 2009:143–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perkins KA, Epstein LH, Grobe J, Fonte C. Tobacco abstinence, smoking cues, and the reinforcing value of smoking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;47(1):107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, et al. . Sex differences in the contribution of nicotine and nonpharmacological stimuli to nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2005;180(2):258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barrett ST, Geary TN, Steiner AN, Bevins RA. Sex differences and the role of dopamine receptors in the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine and bupropion. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2017;234(2):187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barrett ST, Geary TN, Steiner AN, Bevins RA. A behavioral economic analysis of the value-enhancing effects of nicotine and varenicline and the role of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in male and female rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2018;29(6):493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adams S. Psychopharmacology of tobacco and alcohol comorbidity: a review of current evidence. Curr Addict Rep. 2017;4(1):25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meyerhoff DJ, Tizabi Y, Staley JK, Durazzo TC, Glass JM, Nixon SJ. Smoking comorbidity in alcoholism: neurobiological and neurocognitive consequences. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(2):253–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miller NS, Gold MS. Comorbid cigarette and alcohol addiction: epidemiology and treatment. J Addict Dis. 1998;17(1):55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nadal R, Samson HH. Operant ethanol self-administration after nicotine treatment and withdrawal. Alcohol. 1999;17(2):139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Potthoff AD, Ellison G, Nelson L. Ethanol intake increases during continuous administration of amphetamine and nicotine, but not several other drugs. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1983;18(4):489–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smith BR, Horan JT, Gaskin S, Amit Z. Exposure to nicotine enhances acquisition of ethanol drinking by laboratory rats in a limited access paradigm. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1999;142(4):408–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clark A, Lindgren S, Brooks SP, Watson WP, Little HJ. Chronic infusion of nicotine can increase operant self-administration of alcohol. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41(1):108–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lê AD, Corrigall WA, Harding JW, Juzytsch W, Li TK. Involvement of nicotinic receptors in alcohol self-administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(2):155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lê AD, Wang A, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Shaham Y. Nicotine increases alcohol self-administration and reinstates alcohol seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2003;168(1-2):216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barrett SP, Tichauer M, Leyton M, Pihl RO. Nicotine increases alcohol self-administration in non-dependent male smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81(2):197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Acheson A, Mahler SV, Chi H, de Wit H. Differential effects of nicotine on alcohol consumption in men and women. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;186(1):54–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kouri EM, McCarthy EM, Faust AH, Lukas SE. Pretreatment with transdermal nicotine enhances some of ethanol’s acute effects in men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;75(1):55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barrett ST, Bevins RA. A quantitative analysis of the reward-enhancing effects of nicotine using reinforcer demand. Behav Pharmacol. 2012;23(8):781–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Charntikov S, Swalve N, Pittenger S, et al. . Iptakalim attenuates self-administration and acquired goal-tracking behavior controlled by nicotine. Neuropharmacology. 2013;75:138–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychol Rev. 2008;115(1):186–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hursh SR. Behavioral economics and the analysis of consumption and choice. In: McSweeny FK, Murphy ES, eds. The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Operant and Classical Conditioning. New York, NY: John Wiley; 2014:275–305. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bickel WK, Marsch LA, Carroll ME. Deconstructing relative reinforcing efficacy and situating the measures of pharmacological reinforcement with behavioral economics: a theoretical proposal. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2000;153(1):44–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Replacing relative reinforcing efficacy with behavioral economic demand curves. J Exp Anal Behav. 2006;85(1):73–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kenward MG, Roger JH. Small sample inference for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics. 1997;53(3):983–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. TUKEY JW. Comparing individual means in the analysis of variance. Biometrics. 1949;5(2):99–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015; 67(1):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Halekoh U, Højsgaard S. A Kenward-Roger approximation and parametric bootstrap methods for tests in linear mixed models—The R package pbkrtest. J Stat Softw. 2014; 59(9):1–30.26917999 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lenth RV. Least-squares means: the R package lsmeans. J Stat Softw. 2016; 69(1):1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 33. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed August 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barret ST, Bevins RA. Nicotine enhances operant responding for qualitatively distinct reinforcers under maintenance and extinction conditions. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;114-115:9–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Perkins KA, Karelitz JL. Reinforcement enhancing effects of nicotine via smoking. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;228(3):479–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shahan TA, Bickel WK, Madden GJ, Badger GJ. Comparing the reinforcing efficacy of nicotine containing and de-nicotinized cigarettes: a behavioral economic analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1999;147(2):210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shahan TA, Bickel WK, Badger GJ, Giordano LA. Sensitivity of nicotine-containing and de-nicotinized cigarette consumption to alternative non-drug reinforcement: a behavioral economic analysis. Behav Pharmacol. 2001;12(4):277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, et al. . Environmental stimuli promote the acquisition of nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2002;163(2):230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Donny EC, Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, et al. . Operant responding for a visual reinforcer in rats is enhanced by noncontingent nicotine: implications for nicotine self-administration and reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2003;169(1):68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Palmatier MI, Evans-Martin FF, Hoffman A, et al. . Dissociating the primary reinforcing and reinforcement-enhancing effects of nicotine using a rat self-administration paradigm with concurrently available drug and environmental reinforcers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;184(3-4):391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Besheer J, Faccidomo S, Grondin JJ, Hodge CW. Regulation of motivation to self-administer ethanol by mGluR5 in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(2):209–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McBride WJ, Li TK. Animal models of alcoholism: neurobiology of high alcohol-drinking behavior in rodents. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1998;12(4):339–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Perkins KA, Sexton JE, DiMarco A, Grobe JE, Scierka A, Stiller RL. Subjective and cardiovascular responses to nicotine combined with alcohol in male and female smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1995;119(2):205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, et al. . The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009;6(4):e1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]